Comparative analysis of NAFLD-related health videos on TikTok: a cross-language study in the USA and China (original) (raw)

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become the most common chronic liver disease worldwide, covering a disease continuum from steatosis with or without mild inflammation (non-alcoholic fatty liver) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [1], the potential progressive disease course will lead to adverse consequences such as liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death [2], affecting about 25% of the global population [3], and the prevalence will continue to rise rapidly [4,5,6]. In a projection study using a hierarchical Bayesian approach by Le et al., the global prevalence of NAFLD will reach 55.2% by 2040 [7], imposing a huge health and economic burden on patients, their families, and society [8]. However, unlike other diseases that rely on drug interventions, lifestyle interventions (including dietary changes, weight loss, and structured exercise interventions) are the first-line therapies recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines for managing NAFLD, especially for those who have not progressed to NASH or have no fibrosis, early lifestyle interventions can improve or even completely reverse the liver damage caused by NAFLD [9, 10]. Therefore, improving the general public’s awareness and understanding of NAFLD is essential for promoting human health and reducing the disease burden.

As health awareness increases among people, there grows a stronger desire to actively acquire health information [11]. More people are demanding to participate in health care decisions [12], and video social platforms have become important tools for disseminating and acquiring health information [13,14,15]. In recent years, TikTok has become the leader in the short video platform field, with the largest number of daily active users at 780 million compared to other common video platforms [[16](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR16 "TikTok. TikTok revenue and usage statistics (2023). 2023. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics

. Accessed.")\], such as Bilibili in China and YouTube in the United States \[[17](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR17 "Liu H, Peng J, Li L, et al. Assessment of the reliability and quality of breast cancer related videos on TikTok and Bilibili: cross-sectional study in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1296386."), [18](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR18 "Kunze KN, Alter KH, Cohn MR, et al. YouTube videos provide low-quality educational content about rotator cuff disease. Clin Shoulder Elb. 2022;25(3):217–23.")\]. And TikTok is currently the only internationalized short-video platform that is popular in both China and the United States \[[19](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR19 "Wang M, Yao N, Wang J, Chen W, Ouyang Y, Xie C. Bilibili, TikTok, and YouTube as sources of information on gastric cancer: assessment and analysis of the content and quality. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):57."), [20](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR20 "Salka B, Aljamal M, Almsaddi F, Kaakarli H, Nesi L, Lim K. TikTok as an educational tool for kidney stone prevention. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48789.")\], which has quickly developed into a popular channel for spreading health information in both countries, a trend highlighting the increasing influence of digital media in healthcare communication \[[21](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR21 "O’Connor S, Zhang M, Honey M, Lee JJ. Digital professionalism on social media: a narrative review of the medical, nursing, and allied health education literature. Int J Med Inform. 2021;153:104514."), [22](/article/10.1186/s12889-024-20851-9#ref-CR22 "Dee EC, Muralidhar V, Butler SS, et al. General and health-related internet use among cancer survivors in the United States: a 2013–2018 cross-sectional analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(11):1468–75.")\].The quality of short videos on TikTok related to diseases such as liver cancer [23], gallstone disease [24], and diabetes [25] has been fully tested. However, previous studies have indicated that due to the lack of a review mechanism for publishers and content, the quality of health-related videos on the TikTok platform is uneven, often unsatisfactory [11, 15, 23], and even potentially misleading [26, 27]. However, a clear gap in the literature is the lack of research specifically evaluating the quality of NAFLD-related short videos. Given the rising prevalence of NAFLD and increasing use of platforms such as TikTok for health information dissemination, this is a key area for future research. In addition, there is a lack of comparison of the quality of medical and health short videos in Chinese and English in existing studies [14]. This gap is particularly important in the context of global health communication because it hinders our understanding of the potential differences in health information quality between different languages and cultures [15]. Therefore, our cross-sectional study aims to evaluate and compare the quality and reliability of short videos about NAFLD on the American and Chinese versions of TikTok.

Methods

Ethical considerations

This research did not involve any clinical trials, human tissue samples, or the use of laboratory animals. The data utilized in this study was sourced exclusively from TikTok videos that are publicly accessible, ensuring that no personal privacy was compromised. Moreover, since there was no direct engagement with users, ethical approval was not necessary for this project.

Search strategy and data collection

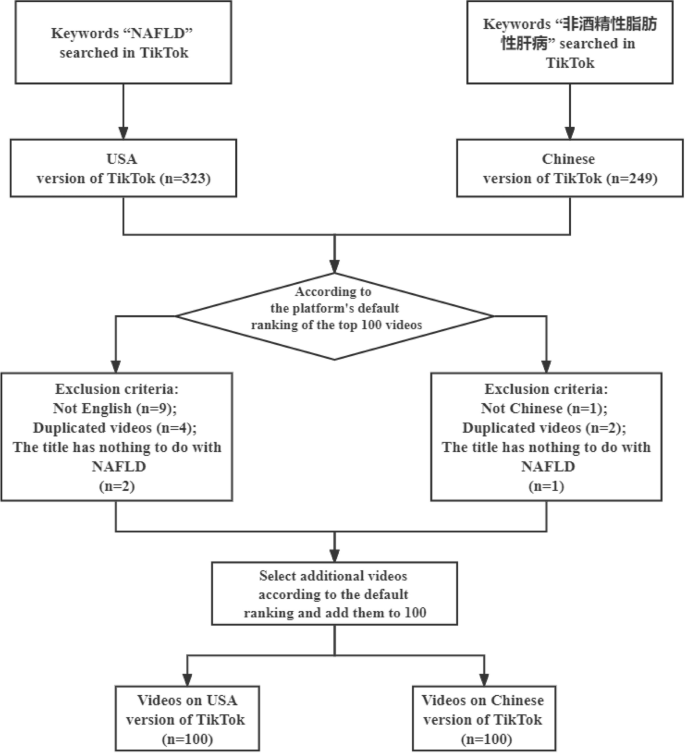

In this cross-sectional study, “NAFLD” and “非酒精性脂肪性肝病” (“NAFLD” in Chinese) were used as the keywords to search for the top 100 videos recommended sorting process in the Chinese version and USA version of TikTok on August 31, 2023, as the same video platform’s different versions ensured homogeneity and comparability between videos from both countries. The videos on the USA version of TikTok were searched and collected by JL in Washington, D.C., USA, while the videos on the Chinese version of TikTok were searched and recorded by JP in Beijing, China. All videos are searched and collected within one day to reduce errors caused by platform algorithm recommendations and video updates. The “top 100 videos” refers to the first 100 videos displayed by default in the TikTok platform’s combined sorting order when users conduct searches. This definition has been validated and applied in numerous studies [19, 23, 24]. Furthermore, these studies indicate that videos ranking above the top 100 are sufficiently representative of all relevant videos in the domain on the TikTok platform and do not exert a significant influence on the overall analysis [19, 23, 24].

To mitigate the potential bias instigated by personalized recommendation algorithms, fresh accounts were established and activated on each video platform. A comprehensive and default ranking system by TikTok was employed. Exclusion criteria were applied to refine the video selection, removing videos that were not in Chinese or English, duplicates (videos sharing identical content but published by different users), and videos with titles that were not pertinent to NAFLD. The selection process continued until a dataset of the top 100 videos was obtained (Fig. 1). The dataset included fundamental information from each video, such as the title, uploader’s name and identity, video duration, content, and engagement metrics (likes, comments, shares, and saves). Additionally, the number of days since the video was published was recorded. All data were meticulously extracted and recorded in Excel (Microsoft Corp). In addition, based on the classification methods used in several studies analyzing short videos related to liver disease [23, 28,29,30], the information about the publisher’s authentication on the platform, and the information about the publisher and the content being displayed in the video, we developed uniform classification criteria to categorize the video publishers and video content on the two versions of TikTok.

Fig. 1

Search strategy and video screening procedure on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Classification of videos

Publishers are classified as: (1) medical practitioners, (2) non-medical practitioners. Medical practitioners are further divided into: (1) liver diseases related experts, (2) non liver diseases related experts; non-medical professionals are further divided into: (1) science communicators, (2) patients. The identities of the medical practitioners were verified on the official websites of their hospitals, and the identities of the non-medical practitioners were based on the platform’s authentication or the information shown in the video.

The video content is classified as: (1) disease, (2) diet and lifestyle, (3) drugs or surgery, (4) news and reports. Specific classification details of video publishers and content are shown in Table 1. Additionally, to facilitate classification by researchers and to assist the audience in better understanding, we have further refined and defined the categories of science communicators and diet and lifestyle. The category of science communicators is further divided into: Individual science communicators, Nutritionists, and Non-profit organizations/institutions. The diet and lifestyle category is further divided into: Diet, Exercise, and Diet combined with Exercise. For detailed definitions, please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1 Classification of videos

The visual background environment in the video is classified as: (1) Ward, (2) Outpatient Department, (3) Office, (4) Private Room, (5) Outdoors, (6) Virtual Background The visual communication design in the video is classified as: (1) Solo narration (no schematic presentation), (2) Sound 2D/3D animation, (3) Solo narration (schematic presentation), (4) Conversation. The visual text in the video is classified as: (1) Subtitles, (2) No subtitles. The criteria for visual background environment, visual communication design and visual text are shown in the supplementary Table 2–4.

Video assessment

Global Quality Scale (GQS) and modified DISCERN (mDISCERN) are used to evaluate video quality and reliability respectively, and Medical Quality Video Evaluation Tool (MQ-VET) is used to comprehensively evaluate the overall quality of videos (including quality and reliability). The detailed scoring standards of GQS, mDISCERN and MQ-VET are shown in supplementary materials (Supplementary Table 5–8).

The videos were scored by two professional reviewers (JL and SL) independently, and any difference in the score is finally scored by the arbitrator (XD). All three are senior experts who have been engaged in hepatobiliary surgery in the affiliated teaching hospital of Chongqing Medical University for more than 15 years and follow the AASLD guidance document when assessing [10]. When evaluating English videos, any questionable medical terms were translated using the Google translate software. The three people carefully reviewed the scoring instructions of GQS, mDISCERN and MQ-VET and reached an agreement on the scoring details. JL and SL summarized and extracted the keywords in the videos. There are 3–5 keywords extracted from each video. Finally, the third expert (XD) merges the synonyms and calculates the frequency of each keyword.

Statistical analyses

The Shapiro Wilk test was used to test the normality of the data. The measurement data of non-normal distribution was expressed as median (IQR) (upper and lower quartiles), and the counting data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Chi square test was used to compare the classified variables and Kruskal Wallis test and Dunn’s test were used to compare the non-normal distribution continuous variables among three or more groups. Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the non-normal distribution continuous variables between two groups. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate the consistency of MQ-VET scores between the two reviewers. ICC ≥ 0.8 was set as good consistency. The Kappa consistency test was used to evaluate the consistency of GQS scores and mDISCERN scores between the two raters, and set Cohen κ ≥ 0.8 indicate good consistency. Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between non normal distribution continuous variables. All the statistical analysis and data visualization were completed by R software (version 4.0.3), P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Following the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 200 videos were selected for data extraction and analysis. Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics of the research samples. The popularity indicators of the Chinese version of TikTok, including “likes”, “comments”, “shares”, and “saves”, are significantly higher than those of the USA version (P < 0.001). Furthermore, there is no significant difference in the duration of videos, but the days since published of videos on Chinese version of TikTok are longer (P < 0.001). In addition, we further documented the popularity indicators on both versions of TikTok by publisher and video content (Supplementary Table 9–12), and detailed analysis of the results is presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of the videos

Video publishers, content, visual background environment, visual communication design and visual text

Regarding the video publishers, there are 118 medical practitioners who account for 59%. In addition, the video publishers of the USA version and Chinese version of TikTok account for the largest proportion respectively in the category “Science communicators” (43%) and category “Non liver diseases related experts” (38%).

On the contrary, according to the video content classification on TikTok, there is no obvious difference between the videos published by China and USA. It should be noted that, as shown in supplementary Fig. 1, the main types of videos published by “patients” are “news and reports”, while medical practitioners and science communicators often publish “disease” and “diet and lifestyle”.

In terms of visual background environment, “office” was the most prevalent in both USA and Chinese videos, accounting for 39% and 36%, respectively. Apart from the “office”, “Private Room” (26%) and “Virtual Background” (17%) were most prevalent in USA videos, while “Outpatient Department” (29%) and “Ward” (15%) were in China (Supplementary Fig. 2). Supplementary Fig. 3A-C shows significant differences in GQS, mDISCERN, and MQ-VET scores for different types of visual communication design (P < 0.001). The supplementary Fig. 3D shows that the proportion of “audio 2D/3D animation” videos on TikTok platform in the United States is significantly larger than that in China, while the proportion of “dialogue” videos is smaller than that in China (P < 0.05). Supplementary Fig. 4A-C shows significant differences in GQS, mDISCERN, and MQ-VET scores for different types of Visual text (P < 0.001). The supplementary Fig. 4D shows that there is no significant difference in the proportion of videos with subtitles between China and the United States.

Video quality and reliability assessments

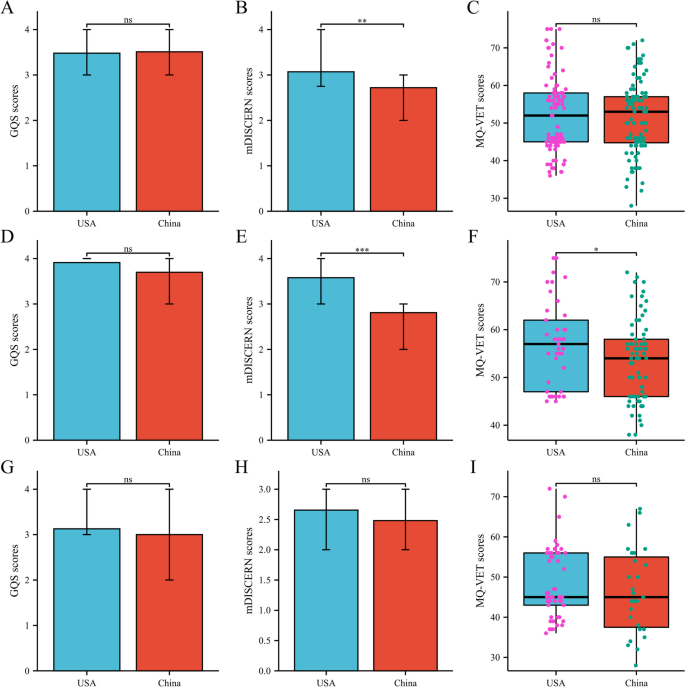

The consistency between the two reviewers for GQS scores and mDISCREN scores was very good, with Cohen’s kappa values of 0.949 and 0.875, respectively. Similarly, the ICC for MQ-VET scores was 0.994, indicating excellent agreement between the two reviewers. In terms of the mDISCERN scores, the videos on the USA version of TikTok are significantly higher than those on the Chinese version (P = 0.003), but there is no significant difference in GQS scores and MQ-VET scores between the two versions (Fig. 2A-C). In the videos published by medical professionals, the videos on the USA version demonstrated significantly higher mDISCERN scores (P < 0.001) and MQ-VET scores (P < 0.05) compared to Chinese version (Fig. 2E, F). In the videos published by non-medical professionals, no significant statistical differences were observed in GQS scores, mDISCERN scores, and MQ-VET scores among the two versions (Fig. 2G-I). In addition, supplementary Fig. 5 shows the quality or reliability grades of videos on tiktok in the two versions.

Fig. 2

Comparison of the quality and reliability of videos on the USA and Chinese versions of TikTok. A-C Overall. D-F Medical practitioners. G-I Non-medical practitioners. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns: nonsignificant

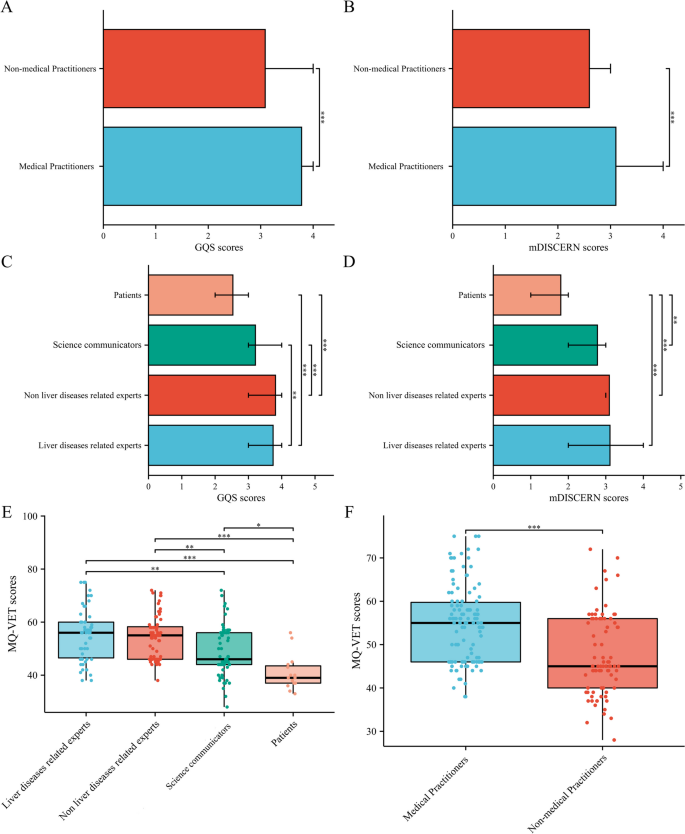

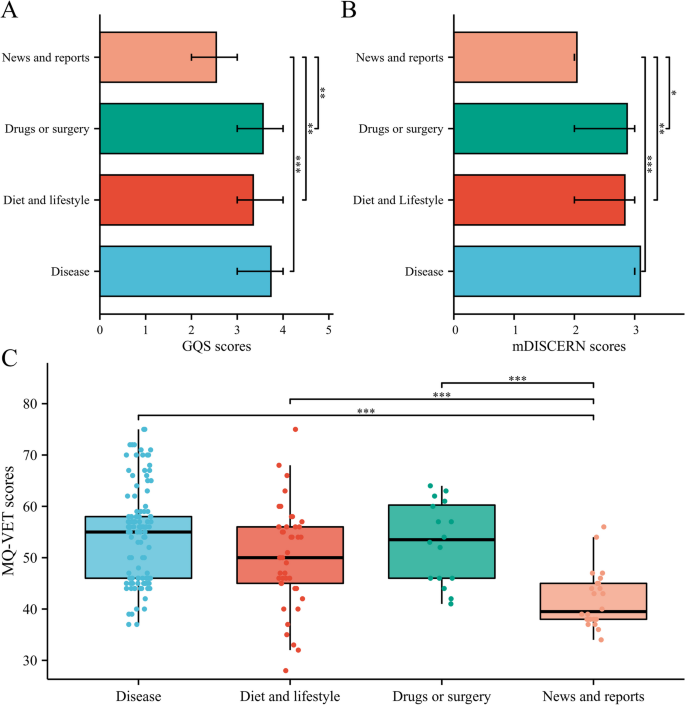

The GQS, mDISCERN, and MQ-VET scores of the videos published by medical practitioners were significantly higher than those published by non-medical practitioners (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A, B, F). Moreover, the comparison of video quality and reliability between publishers of five subgroups is shown in Fig. 3C-E. (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, the mDISCERN scores for videos uploaded by publishers of category “liver disease related experts”, “non liver disease related experts”, and “Science communicators” do not exhibit significant differences. However, the mDISCERN scores for videos uploaded by “liver disease related experts”, “non liver disease related experts”, and “science communicators” are significantly higher than those uploaded by the category “patients” (“liver disease related experts”, “non liver disease related experts” vs “patients”, P < 0.001; “science communicators” vs “patients”, P < 0.01). Furthermore, MQ-VET scores of videos from both liver disease related experts and non-liver disease related experts were significantly higher than videos by science communicators (P < 0.01) and patients (P < 0.001). However, there were still no statistical differences between GQS, mDISCERN and MQ-VET scores of liver disease related experts and non-liver disease related experts. Further analyses of science communicators showed no significant differences in the three rating scales for videos uploaded by “science communicators” (including “individual science communicators”, “Nutritionists” and “Non-profit organizations/institutions”) in the United States and China (Supplementary Fig. 6). Additionally, Fig. 4 shows that the GQS, mDISCERN, and MQ-VET scores for videos on “disease”, “diet and lifestyle”, and “drugs or surgery” are significantly higher than those for “news and reports”. There is no significant difference in GQS, mDISCERN, and MQ-VET scores between videos related to “disease”, “diet and lifestyle” and “drugs or surgery”. The analysis of “diet and lifestyle” indicates that the overall mDISCERN in the United States is significantly higher than that in China (P < 0.001). Further subgroup analysis reveals that the mDISCERN for “Diet” and “Diet combined with Exercise” in the United States is also higher than that in China (P < 0.05), but there are no significant differences in GQS and MQ-VET (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Fig. 3

Comparison of the quality and reliability of videos published by different publishers. A, B, F Medical practitioners and non-medical practitioners. C, D, E Various publishers. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns: nonsignificant

Fig. 4

Comparison of quality and reliability of different video content. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. A Comparison of GQS scores; B Comparison of mDISCERN scores; C Comparison of MQ-VET scores

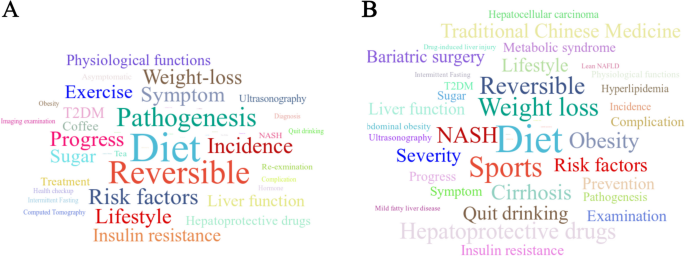

Keywords analysis

The word cloud map is frequently used to highlight the most common keywords in a research field, and it reflects the repetition frequency of words in the sample data [31]. The more frequently the words are mentioned, the larger their sizes become in the selected sample. Figure 5 shows that the top 5 keywords in the USA version of TikTok are “Diet” (n = 59), “Reversible” (n = 38), “Pathogenesis” (n = 25), “Risk factors” (n = 18) and “Incidence” (n = 17), and the top 5 keywords in the Chinese version of TikTok are “Diet” (n = 48), “Sports” (n = 26), “Weight loss” (n = 21), “Reversible” (n = 19) and “NASH” (n = 16). Both sets of keywords are all located in the center of the map, largely and conspicuously. In addition, we also categorized the keywords according to the content of the video, and created a word cloud map respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8A-D).

Fig. 5

Word cloud map. A USA version; B Chinese version

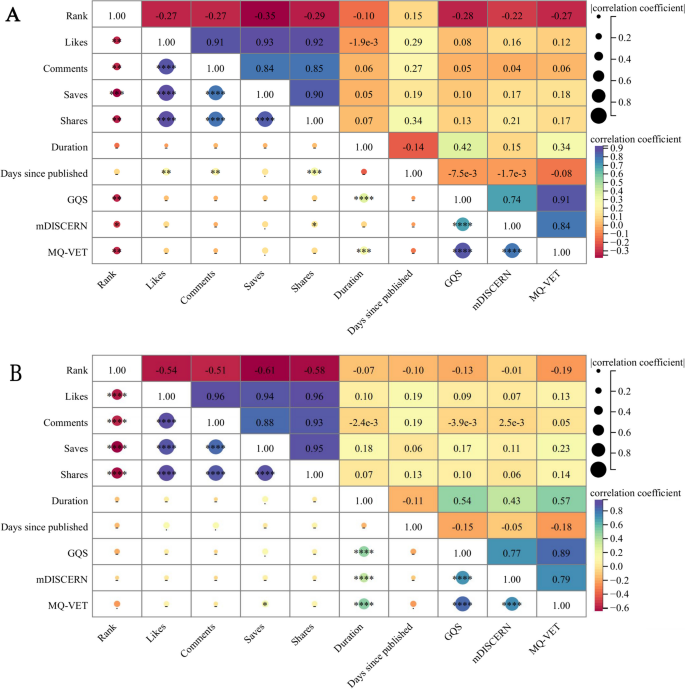

Correlation analysis and linear analysis

Since all variables do not meet the normal distribution, we use the Spearman correlation coefficient to analyze the correlation between variables (Fig. 6). In the USA version of TikTok, GQS scores, mDISCERN scores and MQ-VET scores showed a weak correlation with the ranking. However, in the Chinese version of TikTok, there was no correlation between these variables. In the two versions of TikTok, “duration” has a positive correlation with GQS scores, mDISCERN scores and MQ-VET scores. The GQS scores was not correlated with “likes”, “comments”, “saves” and “shares” in both versions.

Fig. 6

Correlation analysis between different parameters. A USA version; B Chinese version. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; “_” and “.”: nonsignificant

Discussion

The burden associated with NAFLD is becoming a major concern for global health systems [4], and due to a lack of targeted drug treatments, optimizing lifestyle through reasonable intervention has become the fundamental and crucial part of NAFLD treatment [32]. However, participation in structured lifestyle improvement programs may be affected by work and time constraints, making it difficult for patients to benefit [33, 34]. The Internet has provided good conditions for patients to access health information. For example, in Armstrong et al.’s study, high-quality video education significantly improved the disease knowledge and clinical outcomes of patients with atopic dermatitis [35]. But some misleading or even incorrect health education videos may harm people’s health [36, 37]. This is the first study to analyze the quality of short videos in the NAFLD field. Moreover, this is also the first cross-language study of health education videos, revealing potential differences in the patterns of health information dissemination in different language environments by evaluating and comparing Chinese and USA versions of TikTok.

Distribution of video contents, publishers, visual background environment and visual communication design

The distribution of content and publishers can help people understand the differences in the modes of health information transmission in different language environments [38]. Interestingly, from the perspective of video content distribution, the two TikTok versions are consistent. However, there are significant regional differences in the distribution of video publishers. On the USA version of TikTok, the most distributed publishers are science communicators, and medical practitioners account for only 45%, while medical practitioners on the Chinese version of TikTok are as high as 73%. In addition, both medical practitioners and science communicators tend to publish disease-related knowledge, while patients, due to lack of professional medical knowledge, most of their videos are about news and reports. It is worth noting that information published on the Internet, especially about drugs, is sometimes inaccurate, and without proper guidance from health professionals, there is a risk of harmful or improper use of drugs [39]. In our study, content related to drugs or surgery was published by medical practitioners, reducing this risk. Moreover, “metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)” as a new term proposed in 2020 to replace “NAFLD”, not only better reflects the disease process of NAFLD [40], but also helps doctors specifically identify more at-risk patients in clinical practice, especially those with metabolic syndrome [41], therefore it has been increasingly recognized by experts [42, 43]. However, we found that the video content on TikTok in both countries did not mention the related concept of “MAFLD”. It should be noted that in 2023, some experts proposed renaming “NAFLD” to “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)” [44], so future video uploaders should be careful to distinguish these terms.

The difference in visual background environment in Chinese and American videos may be related to the different doctor-patient relationships in the two countries. Due to the traditional cultural respect for authority, Chinese patients tend to accept doctors’ treatments and advice unilaterally, so the visual context is often developed by doctors in wards and outpatient department. In the USA, on the other hand, the doctor-patient relationship tends to be more egalitarian and cooperative, and both doctors and patients have the opportunity and power to express their opinions, so the visual background environment are different from those in Chinese healthcare settings, and are more often developed in private rooms or virtual background. In terms of the visual communication design in the video, the difference in the “Sound 2D/3D animation reflects the difference in culture between the USA and China, as the USA used 2/3D animation earlier in medical education [45].

Quality and reliability of NAFLD short videos

Our study found that the quality of videos about NAFLD on USA and Chinese versions of TikTok is relatively good but the reliability is mediocre, and there is still room for overall quality improvement. Although there is no significant difference in video quality between the two versions, compared to the Chinese version of TikTok, the reliability of the USA version is relatively higher. This is contrary to the research results of Yeung et al. [46], their bibliometrics study showed that USA published far more medical and health-related misinformation on various social media than China. This alerts researchers to pay more attention to short video platforms, the emerging social media for disseminating medical health content. Further, to further investigate the sources of differences in the reliability of Chinese and USA videos, we conducted a subgroup analysis of the publishers. We then found that the reliability of videos published by medical practitioners on the USA version of TikTok is significantly better than the Chinese version. This may be due to the fact that the videos published by medical practitioners in China contain some content related to traditional Chinese medicine, which does not meet our evaluation criteria formulated according to the AASLD guideline [10]. It is worth noting that traditional Chinese medicine might have potential therapeutic effects on NAFLD [47]. Chinese medical practitioners should pay attention and improve the authenticity and accuracy of the video content sources when making popular science videos about NAFLD.

We also found that the quality and reliability of short videos are related to the identity of the publisher and the content. Videos published by medical practitioners are of higher quality but mediocre reliability, and their quality and reliability are significantly higher than those of non-medical practitioners, which is consistent with previous research results [15, 23, 24]. Although medical practitioners have professional knowledge related to diseases, in our study, only 9.3% (11/118) of medical practitioners provided corresponding references and other sources of information in the video at the same time, mDISCERN reached 5 points, causing the overall reliability of the video to be average. Interestingly, the quality and reliability of videos published by liver disease-related experts and non-liver disease-related experts have no statistical difference. This may be due to increasing research evidence that NAFLD is a multi-system disease [48], and is closely related to the risk of extrahepatic complications such as type 2 diabetes [49], cardiovascular disease [50], and chronic kidney disease [51], which has attracted the attention of medical experts from different fields. It should be noted that although the quality of videos published by scientific communicators is lower than that of medical practitioners, there is no significant difference in their reliability, contrary to the previous study by He et al. [15]. This may be related to the fact that science communicators, as non-frontline clinical staff, have insufficient understanding of clinical issues that can actually reflect patient needs. However, due to a lack of professional knowledge, the quality and reliability of videos published by patients are the worst, which may also be related to the possibility that NAFLD has a certain chance of causing cognitive impairment in patients [52]. Meanwhile, news and report videos are mostly from patients and mainly related to their lifestyle, lacking a systematic introduction to the disease situation and the explanation of related disease knowledge, resulting in poor quality and reliability, significantly lower than the other three categories. Furthermore, the specific strategy for lifestyle improvement in NAFLD treatment varies from person to person [53], and the lifestyle of some patients in the news and report videos may not be suitable for promotion.

In addition, we found that video quality and reliability were related to visual communication design and visual text in the video. In terms of visual communication design, the highest quality and reliability were found in the “Solo narration (schematic presentation)” category. This is due to the fact that diagrams and charts are powerful visual aids that can help the audience better understand and memorize information, especially in health education videos that involve a lot of medical expertise [54]. On the other hand, “Conversation” videos often show scenes in outpatient department or wards, which are of poorer quality and reliability due to the lack of systematic knowledge explanation and visual aids. In terms of visual text, the quality and reliability of subtitled videos was much higher than that of non-subtitled videos, as one would expect. This is because subtitled videos provide both visual and auditory information, which enhances the completeness and accessibility of the video information, especially for hearing-impaired or non-native-speaking viewers [55, 56]. Therefore, we recommend supplementing video production with visual aids, such as anatomical diagrams, flowcharts, and captions, to improve the quality and reliability of the videos.

The relationship between video quality and video characteristics

Correlation analysis shows that there is no obvious correlation between the quality of the videos on the Chinese and USA versions of TikTok and “Likes”, “Comments” and “Shares”, which is consistent with previous research results on liver cancer [23]. This indicates that the general audience has limited ability to evaluate health education videos. In addition, we found a clear positive correlation between video length and video quality, as longer videos can accommodate more health information and explain the theme more clearly [57]. However, research by Lena et al. shows that patients may lose interest when watching longer videos [58]. Therefore, the video publishers should strive to provide higher quality health information within a suitable time frame. It is noteworthy that the quality indicators of videos on the USA version of TikTok are weakly correlated with rankings, while no correlation was found in the Chinese version, this may be due to different algorithms recommended in different versions of TikTok. However, this result suggests that the current default algorithm of TikTok possibly limits the viewer’s access to high-quality videos related to NAFLD.

The analysis of word cloud map

The comparison of word cloud maps can help people understand the similarities and differences in the hot issues concerned by audiences and publishers in different regions. Frequently occurring keywords indicate that “Diet” and “Reversible” are common topics of concern in the USA and China. At the same time, the AASLD and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) guidelines have regarded lifestyle intervention as the first-line therapy for managing NAFLD [9, 10, 59]. Lifestyle intervention strategies include diet therapies mainly based on the Mediterranean Diet (MD) and the Ketogenic Diet (KD) [60, 61], and exercise intervention measures combined with resistance and aerobic exercises [32]. The AASLD guideline points out that for those NAFLD patients who have not progressed to NASH and have no fibrosis, the damage to their liver is reversible, and their prognosis is usually good after lifestyle intervention [9, 10]. For the majority of obese patients who cannot reach the ideal weight with lifestyle intervention and internal medicine treatment, the application of bariatric surgery needs to be considered [62, 63]. Many studies in recent years have proven the therapeutic effect of bariatric surgery on NAFLD [64, 65], but as an invasive surgery, more research is needed to confirm its safety [66]. In addition, although various new drugs represented by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) agonists, farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists, and thyroid hormone receptor-β (THR-β) agonists as well as therapies targeting intestinal microbes are being developed for the treatment of NAFLD [32, 67], no drug has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [68], and the commonly used ones are some non-specific “Hepatoprotective drugs” [53], which are reflected in the word cloud maps of both countries. It’s worth noting that the USA audience seems to pay more attention to the “Pathogenesis” and “Risk factors” of NAFLD, which may be related to the rapidly rising incidence of NAFLD in the United States [69]. Mastering its complex pathophysiology can promote the prevention and management of NAFLD [70]. Furthermore, this may also be due to a larger proportion of science communicators among the publishers on the USA version of TikTok, and the videos published by this group are mostly related to “disease”.

From the word cloud map based on the classification of video content, the “disease” videos focus more on the medical expertise related to NAFLD, explaining the pathogenesis, epidemiology, structure of the liver, pathophysiology, and complications, and containing many medical specialized vocabulary, such as hepatic lobule, fatty acid metabolism, and inflammation, so the target groups of these videos are mostly medical students, biomedical related practitioners, and patients/family members with certain biomedical background. “Treatment” videos are more involved in specific drug names (such as silybum, lecithin, and polyene phosphatidylcholine), surgical methods (such as sleeve gastrectomy and liver transplantation), and corresponding surgical indications. In addition, they also cover some drug instructions, adverse reactions, and general non-drug treatment methods. Therefore, the target population of such videos is similar to that of disease videos, but at the same time, they are more inclined to patients who have been diagnosed with NAFLD and have some knowledge of their own condition. “News and reports” videos are usually more general, not based on a specific content of a more in-depth elaboration, or related to the specific experience of some patients, more subjective feelings, but can help part of the general population or patients to understand the diagnosis and treatment process related to NAFLD. “Diet and lifestyle” videos contain relatively less medical vocabulary, but compared with”News and reports” videos, they are more specific, listing some specific knowledge related to diet and exercise, such as aerobic exercise, intermittent fasting and mediterranean diet, which may be easier to be understood and learned by viewers who do not have relevant professional backgrounds.

Potential differences in health information across languages/cultures

Although there was no significant difference in the quality of NAFLD-related short videos on the Chinese and USA TikTok platforms in our study, potential differences that may exist in different cultural and linguistic contexts are somewhat reflected in video content. First, medical practitioners in the United States and China follow different guidelines for the treatment of NAFLD, following the relevant guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) [10] and the Asian Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) [59], respectively. These differences may influence the content of videos produced by medical practitioners due to the different guiding treatment recommendations and emphasis of the guidelines. For example, the AASLD guidelines emphasize the importance of lifestyle interventions, particularly diet and exercise, whereas the APASL guidelines may focus more on the management of metabolic syndrome [59]. This difference may result in videos on the USA version of TikTok discussing more about lifestyle changes, whereas videos on the Chinese version may discuss more about the management of metabolic risk factors. Dietary cultures differ significantly between China and the United States, and these differences may influence the dietary recommendations discussed by lay producers in short videos. For example, the Mediterranean Diet (MD) is widely promoted in the United States as a healthy dietary pattern for the prevention and treatment of NAFLD [60, 61], whereas in China, the traditional dietary pattern may focus more on the intake of grains and plant foods [71]. In addition, compared to China, recipes in the USA are quantified in terms of nutrients and energy [72], and have higher learnability and reliability, which also leads to higher mDISCERN scores for “diet”-related videos in the USA than in China. These cultural differences may lead to content differences in dietary advice in short videos from the two countries, thus affecting the educational value and applicability of the videos. In conclusion, in different languages and cultures, there are certain differences in people’s health concepts, knowledge of diseases and corresponding treatment modalities, so the characteristics of the target culture need to be taken into account when conducting health popularization to ensure that health information is accurately conveyed and easy to understand.

Evaluation and comparison of scientific scoring tools

In this cross-sectional study, we used three scientific scoring scales to assess the quality and reliability of videos: GQS, mDISCERN, and MQ-VET. GQS and mDISCERN are currently common methods for evaluating health-related short videos on TikTok, and have proven their evaluation efficacy in health fields such as inflammatory bowel disease [15], gallstone disease [24], and thyroid cancer [73]. However, these two scales may have certain limitations, and it is difficult for evaluators to objectively evaluate short videos with less comprehensive content based on scoring criteria [23]. Therefore, we also used the MQ-VET scale designed by Guler et al. recently. The MQ-VET scale standardized the evaluation criteria for health education videos, and is more comprehensive, accurate and objective compared to GQS and mDISCERN [74].

Practical significance and future suggestions

Given the increasing prevalence of NAFLD and its status as a silent epidemic with significant health implications, the spread of inaccurate information through low-quality videos can have severe consequences for patients. Thus, we propose the following recommendations to foster a more standardized and comprehensive approach to short videos about NAFLD. First of all, video platforms should strictly audit the identity information of publishers, especially medical practitioners, and should certify and clearly display their identity information and affiliation on the homepage of the publishers. At the same time, the platform should also develop unified standards to categorize professional and non-professional publishers. Secondly, video platforms and video publishers should focus on protecting the privacy of the patient population, especially on the Chinese TikTok platform, which contains a large number of outpatient and ward-type videos that may reveal patient privacy. Finally, considering the professionalism of doctors, we suggest that doctors clearly indicate the corresponding reference or guideline sources and match the corresponding schematic diagrams when producing videos, as well as using more popularized language to convey health knowledge to the public, with a view to taking charge of and producing higher-quality and more credible health education videos.

Limitations

Our research does have some limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study, and the videos related to NAFLD on the TikTok may change over time. Secondly, we only collected the top 100 videos on the TikTok platform, not all videos. However, numerous studies have shown that the top 100 videos as a representative dataset can reflect the overall quality of the field [23, 24, 75, 76]. Third, we only evaluated videos on the single platform TikTok, and the TikTok-recommended videos in non-English-speaking regions such as Europe and Central Asia may not be consistent with those in USA, so the results may not be generalizable to other regions and other popular short video platforms. On the other hand, we did not analyze visual art (lines, shapes, shades, colors, textures) and social context (such as historical background and the influence of ethnic traditional medicine). Therefore, future research should also be analyzed from the perspectives of linguistics and social communication. In addition, when conducting similar cross-sectional studies of medical science videos, the definition of each variable should be standardized, and vague terms should be avoided as far as possible.

Conclusion

Our research evaluated the quality of short videos related to NAFLD on the USA and Chinese versions of TikTok, finding these videos to be of higher quality, but of mediocre reliability. There was no significant difference in video quality between the two versions, but the reliability of videos on the USA version of TikTok was higher than that of the Chinese version. The quality of videos related to “disease”, “diet and lifestyle”, and “drugs or surgery” published by medical practitioners was higher, while the quality and reliability of patient-published videos were poor and lacked practical health education. Additionally, we found that the recommended video sort order in both versions of TikTok cannot reflect the quality and reliability of the videos. It is noteworthy that diet and lifestyle are currently the topics of most focus in the field of NAFLD short videos. In the future, prospective researches on videos in the field of NAFLD needs to be conducted across more languages and platforms to confirm our findings.

References

- Powell EE, Wong VW, Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2212–24.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - a global public health perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;70(3):531–44.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):123–33.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(11):686–90.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhou F, Zhou J, Wang W, et al. Unexpected rapid increase in the burden of NAFLD in China from 2008 to 2018: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2019;70(4):1119–33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Le MH, Yeo YH, Zou B, et al. Forecasted 2040 global prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using hierarchical bayesian approach. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(4):841–50.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2019;69(6):2672–82.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–57.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797–835.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wang L, Li Y, Gu J, Xiao L. A quality analysis of thyroid cancer videos available on TikTok. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1049728.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1):e12454.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ji-Xu A, Htet KZ, Leslie KS. Monkeypox content on TikTok: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e44697.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liang J, Wang L, Song S, et al. Quality and audience engagement of Takotsubo syndrome-related videos on TikTok: content analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(9):e39360.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - He Z, Wang Z, Song Y, et al. The reliability and quality of short videos as a source of dietary guidance for inflammatory bowel disease: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e41518.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - TikTok. TikTok revenue and usage statistics (2023). 2023. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics. Accessed.

- Liu H, Peng J, Li L, et al. Assessment of the reliability and quality of breast cancer related videos on TikTok and Bilibili: cross-sectional study in China. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1296386.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kunze KN, Alter KH, Cohn MR, et al. YouTube videos provide low-quality educational content about rotator cuff disease. Clin Shoulder Elb. 2022;25(3):217–23.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang M, Yao N, Wang J, Chen W, Ouyang Y, Xie C. Bilibili, TikTok, and YouTube as sources of information on gastric cancer: assessment and analysis of the content and quality. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):57.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Salka B, Aljamal M, Almsaddi F, Kaakarli H, Nesi L, Lim K. TikTok as an educational tool for kidney stone prevention. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48789.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - O’Connor S, Zhang M, Honey M, Lee JJ. Digital professionalism on social media: a narrative review of the medical, nursing, and allied health education literature. Int J Med Inform. 2021;153:104514.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dee EC, Muralidhar V, Butler SS, et al. General and health-related internet use among cancer survivors in the United States: a 2013–2018 cross-sectional analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(11):1468–75.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zheng S, Tong X, Wan D, Hu C, Hu Q, Ke Q. Quality and reliability of liver cancer-related short Chinese videos on TikTok and Bilibili: cross-sectional content analysis study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e47210.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sun F, Zheng S, Wu J. Quality of information in gallstone disease videos on TikTok: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e39162.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kong W, Song S, Zhao YC, Zhu Q, Sha L. TikTok as a health information source: assessment of the quality of information in diabetes-related videos. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9):e30409.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yeung A, Ng E, Abi-Jaoude E. TikTok and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a cross-sectional study of social media content quality. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67(12):899–906.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bai G, Fu K, Fu W, Liu G. Quality of internet videos related to pediatric urology in mainland China: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:924748.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cheng D, Ren K, Gao X, et al. Video quality of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on TikTok: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2024;103(34):e39330.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lai Y, He Z, Liu Y, et al. The quality and reliability of TikTok videos on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a propensity score matching analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1231240.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ding R, Kong Q, Sun L, et al. Health information in short videos about metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: analysing quality and reliability. Liver Int. 2024;44(6):1373–82.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Xing J, Liu J, Han M, Jiang Y, Jiang J, Huang H. Bibliometric analysis of traditional Chinese medicine for smoking cessation. Tob Induc Dis. 2022;20:97.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rong L, Zou J, Ran W, et al. Advancements in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1087260.

Article Google Scholar - Sumida Y, Yoneda M. Current and future pharmacological therapies for NAFLD/NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(3):362–76.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mazzotti A, Caletti MT, Brodosi L, et al. An internet-based approach for lifestyle changes in patients with NAFLD: two-year effects on weight loss and surrogate markers. J Hepatol. 2018;69(5):1155–63.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Armstrong AW, Kim RH, Idriss NZ, Larsen LN, Lio PA. Online video improves clinical outcomes in adults with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(3):502–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kılınç DD. Is the information about orthodontics on Youtube and TikTok reliable for the oral health of the public? A cross sectional comparative study. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;123(5):e349–54.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ko BC, Haw S. Evaluation of YouTube videos about isotretinoin as treatment of acne vulgaris. Ann Dermatol. 2022;34(5):340–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Schouten BC, Cox A, Duran G, et al. Mitigating language and cultural barriers in healthcare communication: Toward a holistic approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;S0738-3991(20):0242–1.

- Bogenschutz MP. Drug information libraries on the internet. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(3):249–58.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gofton C, Upendran Y, Zheng MH, George J. MAFLD: how is it different from NAFLD? Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29(Suppl):S17-s31.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lin S, Huang J, Wang M, et al. Comparison of MAFLD and NAFLD diagnostic criteria in real world. Liver Int. 2020;40(9):2082–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kawaguchi T, Tsutsumi T, Nakano D, Torimura T. MAFLD: renovation of clinical practice and disease awareness of fatty liver. Hepatol Res. 2022;52(5):422–32.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al. A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79(3):E93–4.

- Guo J, Guo Q, Feng M, et al. The use of 3D video in medical education: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Sci. 2023;10(3):414–21.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yeung AWK, Tosevska A, Klager E, et al. Medical and health-related misinformation on social media: bibliometric study of the scientific literature. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e28152.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhou Z, Zhang J, You L, et al. Application of herbs and active ingredients ameliorate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease under the guidance of traditional Chinese medicine. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:1000727.

Article Google Scholar - Byrne CD, Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S47-64.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med. 2011;43(8):617–49.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Anstee QM, Targher G, Day CP. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(6):330–44.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Musso G, Gambino R, Tabibian JH, et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(7):e1001680.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Filipović B, Marković O, Đurić V, Filipović B. Cognitive changes and brain volume reduction in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018:9638797.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Raza S, Rajak S, Upadhyay A, Tewari A, Anthony SR. Current treatment paradigms and emerging therapies for NAFLD/NASH. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2021;26(2):206–37.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mbanda N, Dada S, Bastable K, Ingalill GB, Ralf WS. A scoping review of the use of visual aids in health education materials for persons with low-literacy levels. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(5):998–1017.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Birulés-Muntané J, Soto-Faraco S. Watching subtitled films can help learning foreign languages. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158409.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Szarkowska A, Ragni V, Szkriba S, Black S, Orrego-Carmona D, Kruger JL. Watching subtitled videos with the sound off affects viewers’ comprehension, cognitive load, immersion, enjoyment, and gaze patterns: a mixed-methods eye-tracking study. PLoS One. 2024;19(10):e0306251.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ozsoy-Unubol T, Alanbay-Yagci E. YouTube as a source of information on fibromyalgia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24(2):197–202.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lena Y, Dindaroğlu F. Lingual orthodontic treatment: a YouTube™ video analysis. Angle Orthod. 2018;88(2):208–14.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Eslam M, Sarin SK, Wong VW, et al. The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Hep Intl. 2020;14(6):889–919.

Article Google Scholar - Plaz Torres MC, Aghemo A, Lleo A, et al. Mediterranean diet and NAFLD: what we know and questions that still need to be answered. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):2971.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Watanabe M, Tozzi R, Risi R, et al. Beneficial effects of the ketogenic diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2020;21(8):e13024.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chauhan M, Singh K, Thuluvath PJ. Bariatric surgery in NAFLD. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(2):408–22.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Mantzoros CS. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism. 2019;92:82–97.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bower G, Toma T, Harling L, et al. Bariatric surgery and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review of liver biochemistry and histology. Obes Surg. 2015;25(12):2280–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Chavez-Tapia NC, Tellez-Avila FI, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Mendez-Sanchez N, Lizardi-Cervera J, Uribe M. Bariatric surgery for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in obese patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(1):Cd007340.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Eilenberg M, Langer FB, Beer A, Trauner M, Prager G, Staufer K. Significant liver-related morbidity after bariatric surgery and its reversal-a case series. Obes Surg. 2018;28(3):812–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Woodhouse CA, Patel VC, Singanayagam A, Shawcross DL. Review article: the gut microbiome as a therapeutic target in the pathogenesis and treatment of chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(2):192–202.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ferguson D, Finck BN. Emerging therapeutic approaches for the treatment of NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(8):484–95.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(9):851–61.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism. 2016;65(8):1038–48.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jiang K, Zhang Z, Fullington LA, et al. Dietary patterns and obesity in Chinese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2022;14(22):4911.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Murphy MM, Barraj LM, Higgins KA. Healthy U.S.-style dietary patterns can be modified to provide increased energy from protein. Nutr J. 2022;21(1):39.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yang S, Zhan J, Xu X. Is TikTok a high-quality source of information on thyroid cancer? Endocrine. 2023;81(2):270–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Guler MA, Aydın EO. Development and validation of a tool for evaluating YouTube-based medical videos. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191(5):1985–90.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Mueller SM, Hongler VNS, Jungo P, et al. Fiction, falsehoods, and few facts: cross-sectional study on the content-related quality of atopic eczema-related videos on YouTube. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4):e15599.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ferhatoglu MF, Kartal A, Ekici U, Gurkan A. Evaluation of the reliability, utility, and quality of the information in sleeve gastrectomy videos shared on open access video sharing platform YouTube. Obes Surg. 2019;29(5):1477–84.

Article PubMed Google Scholar