Methodological considerations of diet assessment of the older Indian population in the longitudinal aging study in India—Harmonised Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia (LASI-DAD) (original) (raw)

Abstract

Introduction

It is predicted that low-and- middle-income countries like India will bear the maximum brunt of global aging in the near future. Aging societies are increasingly facing higher incidence of cognitive decline and dementia. Research on the potential of dietary patterns as a modifiable lifestyle factor for protection of cognitive health has gained momentum. This study aims at developing a dietary assessment tool-food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) for older Indian adults in the community.

Methodology

An FFQ was developed for the diverse, older population in India to collect data on their food intake over the past 12 months. This was pre and pilot tested leveraging the sample of an ongoing longitudinal study of late life cognition in older adults in India – Longitudinal Aging Study in India- Harmonized Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia (LASI-DAD). The FFQ was pilot tested during the first wave of the study (2017–2020) on a sample of 1125 respondents, updated and modified and finally implemented in the second wave of the study on 4465 respondents (2022–2024). An electronic Computer Assisted personal interview (CAPI) system with the use of tablets was implemented. The LASI-DAD FFQ was translated to 12 Indian languages for collecting accurate data from different regions of the country. A diverse range of food products and list of local food from different parts of India were included.

Results

The challenges faced, lessons learnt and modifications helped shape the final LASI-DAD FFQ. This was implemented in 24 Indian states. It had 4 sections: (A) Food consumption habits (B) Food frequency section (C) Herbal /non herbal/ayurvedic supplements (D) Spice intake. The final questionnaire had 88 food items and median time taken to complete was 31 min. Response rate varied from 97 to 100%.

Conclusion and discussion

The LASI-DAD FFQ proved to be a good tool for dietary data collection from a diverse, older Indian population. It is a single, comprehensive questionnaire adapted to the diverse dietary habits of older Indian population factoring in socio-economic, geographic, cultural, religious and seasonal variations, and it will help explore potential associations between diet and late-life cognition in older Indians.

Highlights

The study focuses on the development of a comprehensive diet assessment questionnaire for a diverse older Indian population from different states in India with distinct food habits.

Use of computer assisted personal interviews (CAPI) ensures convenient data collection from the community and helps facilitate regular, online quality checks and data monitoring.

The LASI -DAD FFQ has special sections on supplements, herbal products, and spice intake, which are integral parts of Indian diet and have garnered interest in their possible associations with cognitive health.

The food frequency section enables data to be directly connected to a program for calculation of nutrients.

The paper explains a comprehensive questionnaire adapted to the diverse dietary habits in India, factoring in socio-economic, geographic, cultural, religious, and seasonal variations.

View this article's peer review reports

Introduction

The global population is aging, and it is predicted that by 2050 80% of the global aging population will be living in the low-and middle-income countries such as India [1]. A growing body of research has investigated the potential of dietary patterns as a modifiable lifestyle factor for protection against cognitive decline [[2](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR2 "Polis B, Samson AO. Enhancing cognitive function in older adults: dietary approaches and implications. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1286725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1286725

."), [3](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR3 "Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet. 2024;404(10452):572–628.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0

.")\]. Poor quality diets (low fruit and vegetable intake and high consumption of saturated fats, salt, and sugars) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of key dementia risk factors including obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, as well as independently linked to increased dementia risk \[[4](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR4 "Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–72.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

."), [5](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR5 "Knight A, Bryan J, Murphy K. Is the mediterranean diet a feasible approach to preserving cognitive function and reducing risk of dementia for older adults in Western countries? New insights and future directions. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;25:85–101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.10.005

.")\]. However, it remains to be seen if these research findings translate to the Indian population, as prior studies have been conducted in high-income countries among predominately Caucasian populations with high levels of educational attainment and literacy \[[6](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR6 "Alladi S, Hachinski V. World dementia: one approach does not fit all. Neurology. 2018;91(6):264–70.

https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005941

.")\]. It is important to understand the diet patterns of older adults so that dietary recommendations can strategically intervene to foster healthy eating habits, which may help in prevention and control of disease condition. Various dietary assessment methods including 24-hour recall, prospective food diaries, and retrospective food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) are commonly used to measure dietary intake/pattern. Semi-quantitative FFQ’s consist of a list of food items with portion size and response categories to indicate the usual frequency of consumption over a certain time. Estimated total energy and nutrient intakes can be calculated as the product of the frequency of consumption of each food item and portion size [[7](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR7 "Lovell A, Bulloch R, Wall CR, Grant CC. Quality of food-frequency questionnaire validation studies in the dietary assessment of children aged 12 to 36 months: a systematic literature review. J Nutr Sci. 2017;6:e16. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2017.12

."), [8](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR8 "Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D. Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires – a review. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(4):567–87.

https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2001318

.")\]. The FFQ is representative of “habitual” intake, and therefore the preferable method of measuring intake for nutrients with very high day-to-day variability. FFQs are versatile tools well-suited for assessing diet in large studies because questionnaire processing is significantly less expensive than food records or diet recalls due to its web-based design. They are also flexible to administer, with a low respondent and time burden, and they are useful for repeating dietary assessment over years [9]. Previous studies indicate that FFQs adequately estimate habitual macro-nutrient intake in adult population when compared to other methods like diet records/recalls [[10](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR10 "Kristal AR, Kolar AS, Fisher JL, et al. Evaluation of web-based, self-administered, graphical food frequency questionnaire. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(4):613–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.017

. Epub 24 Jan 2014. PMID: 24462267; PMCID: PMC3966309.")\]. However, FFQs are memory-based, so respondents may overestimate specific food groups, particularly those which may be under-consumed such as fruits and vegetables. Further, not all FFQ incorporate the quantitative measurement of dietary intake \[[11](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR11 "Corish CA, Bardon LA. Malnutrition in older adults: screening and determinants. Proc Nutr Soc. 2019;78(3):372–9.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118002628

.")\]. To develop accurate and reliable methods to assess dietary intake and construct a single FFQ in diverse populations with varying dietary habits is a continuing challenge [[12](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR12 "Ravindranath V, Sundarakumar JS. Changing demography and the challenge of dementia in India. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(12):747–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00565-x

.")\]. Across India, there is extensive cultural and regional variation in cuisine, food habits, and dietary patterns. Indian diets usually have a three major meal pattern and are primarily cereal and pulse-based diet al.ong with vegetable, fruits, and meats \[[13](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR13 "Sudha V, Anjana RM, Vijayalakshmi P, et al. Reproducibility and construct validity of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing dietary intake in rural and urban Asian Indian adults. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29(1):192–204.")\]. Consequently, previous studies in India have employed short FFQ in geographically limited area or states in India \[[14](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR14 "Vijay A, Mohan L, Taylor MA, et al. The evaluation and use of a food frequency questionnaire among the population in Trivandrum, South Kerala, India. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):383.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020383

.")\]. This paper describes the methodology of developing the LASI-DAD FFQ to assess habitual dietary intake among older Indians over the past twelve months, in an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal study – the Harmonised Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia for the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI-DAD). The methodology of LASI-DAD is detailed in separate publications [[15](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR15 "Lee J, Khobragade PY, Banerjee J, et al. Design and methodology of the longitudinal aging study in India-Diagnostic assessment of dementia (LASI‐DAD). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(S3). https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16737

."), [16](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR16 "Khobragade PY, Petrosyan S, Dey S, Dey AB, Lee J, Authorship Team. Design and methodology of the harmonized diagnostic assessment of dementia for the longitudinal aging study in India: wave 2. J American Geriatrics Society. 2024;(3):jgs.19252.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.19252

.")\]. Briefly, LASI-DAD is a sub-study of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI), an ongoing study that collects socio-economic and health-related data from approximately 73,000 adults aged 45 years and above, representative of India as a country as well as each of the states and union territories. LASI-DAD recruited a sub-sample of LASI participants, who were 60 years or older, using a stratified random sampling strategy, such that the sample is nationally representative of India. The study focuses on identifying factors influencing late life cognition in older Indians by collecting epidemiological data on neuropsychological tests, informant reports, comprehensive geriatric assessment and venous blood collection and assays \[[15](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR15 "Lee J, Khobragade PY, Banerjee J, et al. Design and methodology of the longitudinal aging study in India-Diagnostic assessment of dementia (LASI‐DAD). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(S3).

https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16737

."), [16](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR16 "Khobragade PY, Petrosyan S, Dey S, Dey AB, Lee J, Authorship Team. Design and methodology of the harmonized diagnostic assessment of dementia for the longitudinal aging study in India: wave 2. J American Geriatrics Society. 2024;(3):jgs.19252.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.19252

.")\].Methodology

Development of LASI-DAD FFQ

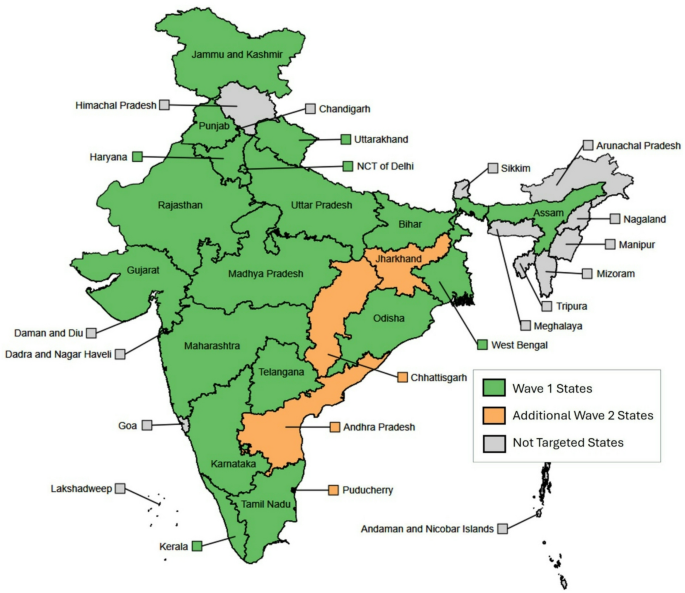

An FFQ was developed to ascertain the food and beverage intakes of older Indians with varied dietary habits, taking guidance from existing literature [17]. The aim was to develop a semi-quantitative, interviewer-administered FFQ which can be easily completed within a Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI), available on a portable tablet device which helps in seamless administration of the pre-coded FFQ survey in the field. Inclusion of a carefully selected, diverse food item list incorporated regional food choices in both rural and urban areas covering North, South, East, West and Central zones of the country covering 22 states and Union territories in India (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Shows the 22 states of India which have taken part in the wave 1 (2017–2020) and 2 (2022–2024) of the LASI-DAD

Construction of food list according to regional variation

As the first step in developing the FFQ, food lists were constructed based on inputs from representatives and nutrition experts from different states. These consisted of food items typically consumed, such as cereals, pulses, vegetables (green leafy and other vegetables, roots and tubers), fruits, desserts, snacks and beverages etc. The regional names and specific variations of foods, beverages, and spices were identified in consultation with regional experts. An extensive list of foods and supplements commonly used by older Indians was also compiled. Food with roughly similar main food group items were grouped together to reduce the length of the questionnaire. Grouping decision was taken by including food items in same groups based on food groups with approximately similar macro-nutrient content.

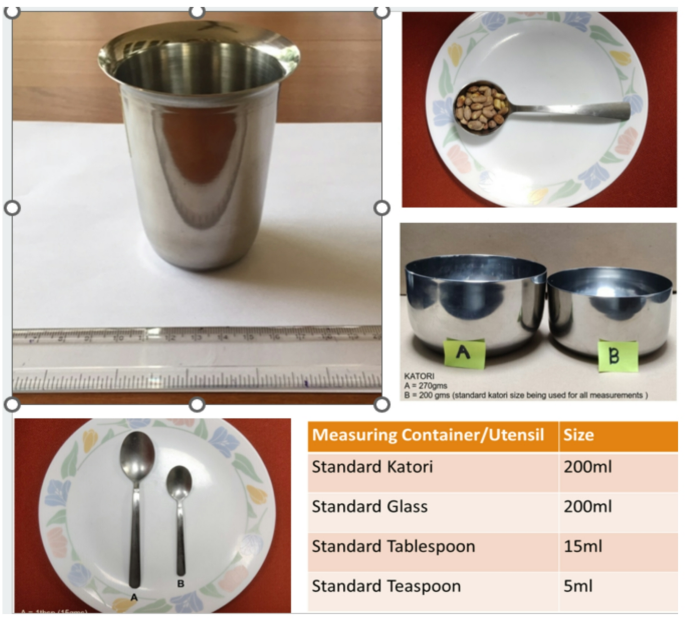

Portion size

Standardized measures or utensils, like bowls (commonly called katori), glasses, teaspoons, or tablespoons were used to determine portion size in the FFQ. Figure 2 These measures have been used in similar studies [[11](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR11 "Corish CA, Bardon LA. Malnutrition in older adults: screening and determinants. Proc Nutr Soc. 2019;78(3):372–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118002628

."), [18](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR18 "Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. Mind diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1007–14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.009

.")\]. These references were shown to the respondents during data collection. For circular items such as Indian breads (e.g., chappati or puri), a reference model was developed to show to respondents. Some items such as bread slices and salty snacks were recorded as integer multiples of standard portion sizes. Fruits were typically recorded in average serving size.Fig. 2

Common measures and household utensils used for measurement of portions in India like Glass, Katori or bowl, table spoon, teaspoon. A standard bowl called Katori in local language used for curry/dal(lentil) measures 200 ml.A standard glass used for consuming water, tea, juice etc measures 200 ml, a standard table spoon and teaspoon measures 15 and 5 ml respectively. Abbreviation: ml- millilitre

Frequency categories and servings

The FFQ included nine response categories to capture frequency of consumption of a standard serving of food and beverage item over the previous 12 months. Nine frequency categories were included: “never or less than once per month,” “1–3 times per month,” “once per week,” “2–4 times per week,” “5–6 times per week,” “once per day,” “2–3 times per day,” “4–5 times per day,” and “6 + times per day.”

Seasonal converter

There are noticeable variations in diet in India depending on seasonal agricultural production, which further varies by region. Although the global marketplace has lessened seasonal influences, fresh fruits and vegetables are most likely to be affected by seasonal changes. Previous studies have reported seasonal variance in frequency of intake in certain items [[19](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR19 "Subar AF, Frey CM, Harlan LC, Kahle L. Differences in reported food frequency by season of questionnaire administration: the 1987 National Health Interview Survey. Epidemiology. 1994;5(2):226–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199403000-00013

.")\]. A participant may indicate that they consume a particular food during a specific season, such as mango or watermelon, which are seasonal fruits growing during the summer season in India. Given that a season approximately spans three months, a Seasonal Converter helped select the more accurate frequency response per the answer given over the past 12 months in total. Interviewers were trained to use this converter to ascertain the frequency of consumption.Standard operating procedure manual

A standard operating procedure (SOP) manual was developed to help train interviewers. This provided guidance to interviewers on all aspects of data collection within the LASI-DAD project including description and background of the study, detailed description of the FFQ, fieldwork protocol, troubleshooting tips during data collection and data processing, and coding.

Fieldwork protocol, data monitoring and quality control, data processing

Field team selection, training, certification and implementation

Field team selection

The LASI-DAD team recruited a team of interviewers for fieldwork in each state based on pre-determined criteria set by the central project management team [[20](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR20 "Banerjee J, Jain U, Khobragade P, et al. Methodological considerations in designing and implementing the harmonized diagnostic assessment of dementia for longitudinal aging study in India (LASI-DAD). Biodemography Soc Biol. 2020;65(3):189–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2020

. PMID: 32727279; PMCID: PMC7398273.")\]. A dietician was recruited to the field teams of interviewers wherever feasible. Before each phase of the fieldwork, a centralised training for all interviewers from different states was organised, which helped standardize the interview technique and data collection across all study centres. This training was followed by site preparation and initiation of data collection.Training

Two selected interviewers from each field team (a dietician and/or nurse/public health professional) received appropriate training led by the diet team to administer and code the FFQ. The importance of good interpersonal skills, building rapport with respondents and diet informants, and non-judgmental interaction was emphasized. Training session involved explanations of the importance of diet in cognition studies, accurate dietary assessment, introduction to the FFQ, thorough explanation of food groups, portions, and frequency categories within the FFQ (including the conversion of home utensils and measures to standard ones), and guidance on administration of the FFQ. The technicalities of using CAPI for administering FFQ were also explained. The training session helped the interviewer to choose the most appropriate frequency response for each food item. Use of seasonality converter was explained so as to select the appropriate frequency category for food items taken specifically during particular seasons. Practice sessions were conducted for re-enforcement.

Certification

After completing training and practice, the interviewers were given an opportunity to engage in role play in pairs, practicing administering the FFQ in the CAPI. The interviewers were evaluated during the role play with the help of an 8-item competency checklist. They were certified to conduct diet interviews after satisfactory performance in all aspects of the checklist.

Implementation

The LASI- DAD FFQ was completed by interviewing the most suitable person from the house-hold who was knowledgeable about respondent’s diet and food purchased and/or cooked in the household and could provide correct information regarding the diet of the respondent. They were mostly women in the household like wife, daughters-in law, daughters etc. This person was named as the “diet informant.” The administration of LASI -DAD FFQ was started after taking signed, informed consent. The consent and interview were done in the diet informants’ language. The interviewer commenced the interview with a brief introduction and explanation about the diet study and the LASI-DAD FFQ. The interviewers conducted the interview as per their training, in a neutral manner, avoiding suggestive terms like “diet,” “health,” or “healthy eating,” which could have encouraged socially acceptable answers from the diet informant and led to incorrect data collection.

Data monitoring and quality control

The CAPI system helped monitor data collection. Data was also reviewed by the study team every two weeks for the initial phases of the LASI-DAD Wave 2 rollout. Eventually, after the data collection was streamlined, the checks were conducted as deemed necessary. The distribution of response to each item in the FFQ was examined. Wherever the data collected did not fall within the norm, it was investigated and the field teams questioned. A quality control (QC) protocol was designed and included in the SOP manual to examine fieldwork progress and raise an alarm whenever unusual response patterns were observed (e.g., extreme values, missing data, and/or unusually short or lengthy interview time) all of which may signal potential issues in fieldwork implementation. The monitoring team also examined variations across sites and among interviewers to identify any systematic biases from specific sites or interviewers. This helped detect and correct any probable challenges early so that the data collected was ultimately optimal.

Data processing

A coding framework was developed that enabled automated conversion of reported food frequencies into estimated daily intakes of foods and beverages (expressed in grams or millilitres per day). This framework generated a standardized CSV file, which will serve as the basis for subsequent nutrient analysis, thereby reducing the risk of manual data entry and coding errors.

For nutrient analysis, we constructed a bespoke food composition database tailored to the LASI-DAD FFQ. This database was created on the Nutritics Research Software platform, using the Indian Food Composition Tables (IFCT) as the primary reference source and supplemented with international food composition datasets where necessary to ensure completeness [21]. Each food item in the CSV file was assigned a unique code, enabling automated linkage to the database and facilitating the nutrient analysis. The details of this process are extensive and are the focus of a separate manuscript currently in preparation.

Results

General considerations

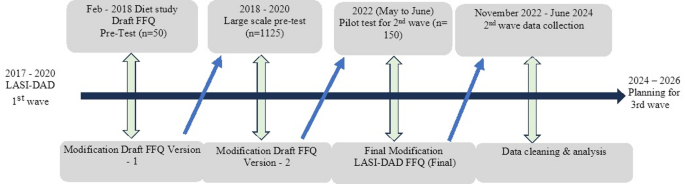

The initial draft of LASI-DAD FFQ developed during the first wave of LASI-DAD in February, 2018 consisted of 234 food items and was a lengthy questionnaire taking approximately 55 ± 5 min to complete. A pre-test was done on a small sample of 50 participants from the Geriatric Medicine out-patient department of a tertiary care hospital in North India with similar age characteristics (60 year and above) as that of study sample. We used a convenience sample of older adults accessing the Geriatric medicine out-patient services. Very sick or moribund patients i.e. patients who needed assistance from caregivers or lying/stretcher bound patients, patients who were visibly in pain or discomfort, were not included in this pre-test. The aim was to check the usability of the questionnaire, get general feedback from participants about the ease of answering the questions and time taken to complete the FFQ. The focus was to keep the newly formed questionnaire simple and non-technical so that it can be answered by the target population i.e. older adults with minimal formal education. After incorporating changes based on observations from the pretest, the FFQ was translated into twelve Indian languages for the different states that would be involved in data collection. Back translation was fulfilled with the help of experts from different states. Translated LASI-DAD FFQ for different states was uploaded in the CAPI format. A large-scale pre-test was done on a LASI-DAD sample during the first wave data collection of the study from 2018 to 2020, resulting in further modifications. The modified FFQ was then piloted on a sample of 150 (50 each from communities in 3 states) from May to July 2022. Feedback from this fieldwork experience steered the final modifications of the FFQ and its incorporation in the second wave data collection (Table 1).

Table 1 Finding from the Pre and Pilot testing and steps in refining the LASI-DAD FFQ

Steps in refining of the FFQ

The following observations from the pre- and pilot study facilitated final modification:

- Comprehension of language used in the questionnaire by the target population, i.e., older adults with minimal formal education, had to be considered. Inputs were taken from the respondents, their caregivers, and technical field staff administering the questionnaire to make subtle changes and adjust the FFQ until it was satisfactory.

- Administration time of the diet interview had to be kept brief to avoid respondent fatigue. The diet interview is a part of a more detailed interview involving cognitive tests, geriatric assessment, mood and affect, and functional status of the respondent. With each refinement, the time taken to complete the questionnaire was reduced.

- To obtain an estimate of portion size, commonly used utensils in Indian households like glasses, Katori, and spoons of three different sizes were used during pre-test. However, this process proved confusing and logistically cumbersome. It was decided that future data will be collected with reference to one standard size of all utensils. (Katori and glass).

- It was observed after the first pre-test that in a typical Indian, multi-generational household food purchasing was done by younger members. Therefore, the older respondent may not be able to answer questions about purchases in the first section of the FFQ. Cognitive impairment or failing memory also posed an impediment in eliciting correct responses from the respondent. To combat this issue, in the second pre-test, the FFQ was administered to the respondent in the presence of a “diet informant.” The “diet informant” assisted the older respondent in answering the interview as they were knowledgeable about the respondent’s diet. This helped in reducing respondent fatigue and superior data collection.

- Skip options were provided in the CAPI wherever required (for example vegetarians and non-vegetarians) so that questions pertaining to these specific groups were asked accordingly. This made the FFQ more concise.

- The lengthy list of similar items like dairy goods, vegetables, snacks etc. consumed grouped together items depending on macronutrient content like fat or calorie content.

- After large-scale pilot testing, it became clear that interviewers required more comprehensive training. To address this deficit, more time for training, practice, and certification of the interviewers was introduced.

- The Spice section in the FFQ had an exhaustive list of spices used in India. After the pilot study it was found that consumption was limited to a few spices and commercially available mixtures of spices. Thus, it was difficult to obtain individual consumption of each spice. Therefore, the spice consumption section was shortened and questions were limited to the use of seven spices used for medicinal or therapeutic purposes.

- Cereals form a major portion of Indian dietary pattern. It was observed after large scale pre-test data collection that cereal consumption reported was unusually low. Major staple cereal intake in the meals in Indian population is either rice or wheat [22]. Some parts of western and central India are more dependent on millets and in southern India combination of cereal and pulses is commonly consumed. The cereal intake section was further refined for accurate data collection into the following sections: (i) staple cereal- rice, wheat, others, (ii) cereal and pulse combinations, (iii) millets, (iv) ready-to-eat cereals.

- Options for desserts, savoury options, and snacks were reduced and made state- and region-specific.

- A timeline of the LASI -DAD diet study has been depicted as a timeline (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Timeline of LASI-DAD diet methodology Study (2017-2024) Abbreviation: LASI-DAD – Longitudinal Aging Study in India-Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia, FFQ-Food Frequency Questionnaire

Composition of the final LASI-DAD FFQ

The final LASI-DAD FFQ comprised of four sections, like the original prototype. The FFQ is included in Table 2 and its four sections are described in greater detail below.

Table 2 Depiction of the LASI -DAD Food Frequency Questionnaire

Section A included questions regarding general food consumption habits, including information on food purchasing, preparation, cooking, and eating habits. This included information on types of fat and milk intake, quantity of sugar and salt intake, and knowledge about dietary habits like vegetarianism/alcohol intake etc.

Section B is the semi-quantitative food frequency section of the questionnaire where questions are asked about the frequency of consumption of a standard portion of food and beverage items in the different sections (modified to suit the Indian diet diversity) over the past 12 months. For each food, a standard portion was indicated/shown (for example numbers, standard utensils). Participants choose from frequency options provided (daily, weekly, monthly etc.) for different food groups (cereals, pulses, fruits, vegetables, nuts and meat). Regional names for each food item in different states were incorporated and items specific to a particular region/state (like locally grown vegetables and fruits) were displayed as a dropdown menu.

Section C consists of questions regarding herbal and multivitamin supplement intake over the past 12 months. During the process of refinement, the list of supplements was made age-specific, such as calcium, iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D3 etc. Commonly used over-the-counter, ayurvedic, and herbal supplements which are associated with cognition were also added (e.g., Ashwagandha, Sakhapushpi) [[23](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR23 "Srivastava V, Mathur D, Rout S, Mishra BK, Pannu V, Anand A. Ayurvedic herbal therapies: a review of treatment and management of dementia. CAR. 2022;19(8):568–84. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205019666220805100008

.")\]. Section D contains questions on intake of seven selected spices potentially relevant for brain health over the past 12 months used for medicinal purpose (Table 2, overview of FFQ).

The final LASI-DAD FFQ was administered in Wave 2 of LASI-DAD, had 88 food items, and took 31 min (SD ± 15 min) to complete. 4465 study participants completed the FFQ, with approximately 58% of the respondents being females (n = 2585). Overall response rate across states was 97%. Special missing values were allotted for ‘don’t know’ and ‘refuse’ responses which will be presented as such in the data released in public domain. 43% of respondents were in the 70–79 year age group, and 70% lived in the rural parts of the country. About 61% of the diet informants were women, mostly daughters-in-law (28%) and spouses (21%) of the main respondent. The time taken to complete the questionnaire was brought down from 55 ± 5 min to 31 ± 15 min.

Strengths, limitations and future direction

Strength

The strength of the study lies in developing a single, culturally-appropriate, comprehensive questionnaire for the older population that is inclusive of diverse food items from different parts of the country. The use of CAPI helps in data collection from the community and ensures efficient quality checking and data monitoring. Inclusion of herbs, spices, and supplements frequently used by older Indians makes it more age-specific and can help in observing their association with cognitive status. Use of a seasonal converter makes the tool more specific for regions like India which have well defined seasons.

Limitations

The potential for recall bias, more so in older, cognitively challenged adults and reduced accuracy compared to more detailed methods of diet data collection is a limitation of the study. Bias due to interpretation and documentation of response of the respondent by interviewers cannot be overlooked. Distinct food habits and food preparation methods pose a deterrent in capturing exact dietary data from a culturally divergent population from different states in India. Lack of formal education in older Indians from rural and remote parts is a limiting factor for self-reported measures and we have to rely on the more labour intensive, interview administered questionnaires for the time being.

Future directions

LASI-DAD has completed second wave of data collection and third wave of the study is scheduled to start in later part of 2026. In the next steps, validation of the FFQ will be conducted with the help of biomarkers that reflect dietary intake and other traditional validation methods before commencement of the third wave of data collection. A food composition dataset has been developed for the LASI-DAD FFQ to enable nutrient analysis of the data collected in the future.

Conclusion and discussion

Accurate assessment of dietary intake in older adults is vital for monitoring nutritional status, managing chronic diseases, and developing effective public health interventions [[24](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR24 "Gupta A, Prakash NB, Sannyasi G. Rehabilitation in dementia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43(5suppl):S37–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176211033316

.")\]. Despite challenges, especially in culturally diverse regions like India, adopting best practices and leveraging technology can enhance the accuracy of dietary assessments such as FFQs \[[25](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR25 "Puri S, Shaheen M, Grover B. Nutrition and cognitive health: a life course approach. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1023907.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1023907

.")\]. Continued research and adaptation of assessment tools are essential to meet the evolving needs of the aging population. Successful dietary assessment tools must also address the main challenges of avoiding respondent fatigue, including food items from geographically diverse areas with expansive lists of state-/region-specific foods.Diet has long been recognised as an important environmental lifestyle factor with immense effect on the cognitive health of elderly populations, especially given that older people are prone to malnutrition, which is defined by the World Health Organization as having “deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients.” [[26](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR26 "Goulet J, Nadeau G, Lapointe A, Lamarche B, Lemieux S. Validity and reproducibility of an interviewer-administered food frequency questionnaire for healthy French-Canadian men and women. Nutr J. 2004;3(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-3-13

."), [27](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR27 "Daniel CR, Kapur K, McAdams MJ, et al. Development of a field-friendly automated dietary assessment tool and nutrient database for India. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(1):160–71.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513001864

.")\] The fast-aging population of India is expected to witness a dramatic rise in late-life cognitive impairment and dementia incidence \[[28](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR28 "Besora-Moreno M, Llauradó E, Tarro L, Solà R. Social and economic factors and malnutrition or the risk of malnutrition in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):737.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030737

.")\]. Given the scale of this issue and the increasingly aging population of India, high-quality nutritional research is a necessity in this region \[[29](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR29 "Nichols E, Vos T. The estimation of the global prevalence of dementia from 1990-2019 and forecasted prevalence through 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease (GBD) study 2019. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(S10):e051496.

https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.051496

.")\]. It has been observed that there is a high burden of vascular and cardiometabolic risk factors in India which can have a major adverse impact on onset and progression of dementia \[[12](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR12 "Ravindranath V, Sundarakumar JS. Changing demography and the challenge of dementia in India. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(12):747–58.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00565-x

.")\]. Moreover, the diverse Indian population in terms of socio-economic, cultural, linguistic, geographical, lifestyle-related and genetic factors, poses a challenge in identifying risk and protective factors for this condition \[[30](/article/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9#ref-CR30 "Melzer TM, Manosso LM, Yau S, yu, Gil-Mohapel J, Brocardo PS. In pursuit of healthy aging: effects of nutrition on brain function. IJMS. 2021;22(9):5026.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22095026

.")\]. Thus, investing in good quality longitudinal studies looking into these factors and their co-relation with aging and cognitive impairment will be very fruitful. LASI-DAD is one such study that includes not only effective clinical and cognitive assessments of older Indians but also brain imaging, detailed genetic analysis, measurement of blood biomarkers, and assessment of lifestyle and environmental factors such as diet and pollution, which might affect late life cognition. Adapting assessment tools to account for cultural and regional dietary patterns, particularly in diverse populations like India, improves relevance and accuracy. The LASI-DAD FFQ is a robust attempt to streamline dietary assessment in older Indians to capture data that can guide timely health interventions.Data availability

Data used in the current study is available upon reasonable request to the Corresponding Authors- Dr. Joyita Banerjee and Dr AB Dey.

Abbreviations

FFQ:

Food frequency questionnaire

LASI-DAD:

Longitudinal Aging Study in India-Harmonised Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia

CAPI:

Computer Assisted Personal Interviews

SOP:

Standard Operating Procedure

References

- United Nations. World population prospects 2024: summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2024/TR/NO. 9. New York: United Nations; 2024. Google Scholar.

Book Google Scholar - Polis B, Samson AO. Enhancing cognitive function in older adults: dietary approaches and implications. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1286725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1286725.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Livingston G, Huntley J, Liu KY, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet. 2024;404(10452):572–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8.

Article Google Scholar - Knight A, Bryan J, Murphy K. Is the mediterranean diet a feasible approach to preserving cognitive function and reducing risk of dementia for older adults in Western countries? New insights and future directions. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;25:85–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.10.005.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Alladi S, Hachinski V. World dementia: one approach does not fit all. Neurology. 2018;91(6):264–70. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005941.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lovell A, Bulloch R, Wall CR, Grant CC. Quality of food-frequency questionnaire validation studies in the dietary assessment of children aged 12 to 36 months: a systematic literature review. J Nutr Sci. 2017;6:e16. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2017.12.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D. Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires – a review. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(4):567–87. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2001318.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Shim JS, Oh K, Kim HC. Dietary assessment methods in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:E2014009.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kristal AR, Kolar AS, Fisher JL, et al. Evaluation of web-based, self-administered, graphical food frequency questionnaire. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(4):613–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.017. Epub 24 Jan 2014. PMID: 24462267; PMCID: PMC3966309.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Corish CA, Bardon LA. Malnutrition in older adults: screening and determinants. Proc Nutr Soc. 2019;78(3):372–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665118002628.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ravindranath V, Sundarakumar JS. Changing demography and the challenge of dementia in India. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(12):747–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00565-x.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sudha V, Anjana RM, Vijayalakshmi P, et al. Reproducibility and construct validity of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing dietary intake in rural and urban Asian Indian adults. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29(1):192–204.

PubMed Google Scholar - Vijay A, Mohan L, Taylor MA, et al. The evaluation and use of a food frequency questionnaire among the population in Trivandrum, South Kerala, India. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020383.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lee J, Khobragade PY, Banerjee J, et al. Design and methodology of the longitudinal aging study in India-Diagnostic assessment of dementia (LASI‐DAD). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(S3). https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16737.

- Khobragade PY, Petrosyan S, Dey S, Dey AB, Lee J, Authorship Team. Design and methodology of the harmonized diagnostic assessment of dementia for the longitudinal aging study in India: wave 2. J American Geriatrics Society. 2024;(3):jgs.19252. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.19252.

Article Google Scholar - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary assessment: A resource guide to method selection and application in low resource settings. Rome: FAO Google Scholar; 2018.

Google Scholar - Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. Mind diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1007–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.009.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Subar AF, Frey CM, Harlan LC, Kahle L. Differences in reported food frequency by season of questionnaire administration: the 1987 National Health Interview Survey. Epidemiology. 1994;5(2):226–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199403000-00013.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Banerjee J, Jain U, Khobragade P, et al. Methodological considerations in designing and implementing the harmonized diagnostic assessment of dementia for longitudinal aging study in India (LASI-DAD). Biodemography Soc Biol. 2020;65(3):189–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2020. PMID: 32727279; PMCID: PMC7398273.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Longvah T, An̲antan̲ I, Bhaskarachary K, Venkaiah K, Longvah T. Indian food composition tables. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research; 2017.

Google Scholar - Raghuram N, Anand A, Mathur D, et al. Prospective study of different staple diets of diabetic Indian population. Ann Neurosci. 2021;28(3–4):129–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/09727531211013972.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Srivastava V, Mathur D, Rout S, Mishra BK, Pannu V, Anand A. Ayurvedic herbal therapies: a review of treatment and management of dementia. CAR. 2022;19(8):568–84. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205019666220805100008.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gupta A, Prakash NB, Sannyasi G. Rehabilitation in dementia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43(5suppl):S37–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176211033316.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Puri S, Shaheen M, Grover B. Nutrition and cognitive health: a life course approach. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1023907. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1023907.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Goulet J, Nadeau G, Lapointe A, Lamarche B, Lemieux S. Validity and reproducibility of an interviewer-administered food frequency questionnaire for healthy French-Canadian men and women. Nutr J. 2004;3(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-3-13.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Daniel CR, Kapur K, McAdams MJ, et al. Development of a field-friendly automated dietary assessment tool and nutrient database for India. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(1):160–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114513001864.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Besora-Moreno M, Llauradó E, Tarro L, Solà R. Social and economic factors and malnutrition or the risk of malnutrition in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):737. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030737.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nichols E, Vos T. The estimation of the global prevalence of dementia from 1990-2019 and forecasted prevalence through 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease (GBD) study 2019. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(S10):e051496. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.051496.

Article Google Scholar - Melzer TM, Manosso LM, Yau S, yu, Gil-Mohapel J, Brocardo PS. In pursuit of healthy aging: effects of nutrition on brain function. IJMS. 2021;22(9):5026. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22095026.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and families who took part in the LASI-DAD study, the faculty and staff at the study sites, and the personnel involved in the data collection and data release.

Funding

This study is a sub-part of the LASI-DAD project which is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Health (R01 AG051125).

Author information

Author notes

- Joyita Banerjee and Alka Mohan Chutani contributed equally and share co-first authorship.

Authors and Affiliations

- Center for Economic and Social Research, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Joyita Banerjee, Alka Mohan Chutani, Pranali Khobragade, Anushikha Dhankhar, Sandy Chien, Sarah Petrosyan, Michael Markot, Bas Weerman & Jinkook Lee - Venu Geriatric Institute, New Delhi, 110017, India

Steffi Jacob, Diksha Agrawat, Istikhar Ali & AB Dey - Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University, Belfast, UK

Claire McEvoy & Danielle Logan - National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, India

Harshita Vishwakarma - Maze research, Mumbai, India

Ankur Jyoti Deka, Khursid Alam & Basani Murali Mohan - Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Peifeng Hu - Department of Biophysics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Sharmistha Dey

Authors

- Joyita Banerjee

- Alka Mohan Chutani

- Claire McEvoy

- Danielle Logan

- Pranali Khobragade

- Steffi Jacob

- Anushikha Dhankhar

- Harshita Vishwakarma

- Sandy Chien

- Sarah Petrosyan

- Michael Markot

- Diksha Agrawat

- Ankur Jyoti Deka

- Khursid Alam

- Basani Murali Mohan

- Istikhar Ali

- Bas Weerman

- Peifeng Hu

- Sharmistha Dey

- Jinkook Lee

- AB Dey

Contributions

i) Designed and oversaw entire project: JL, ABD, SD, CM, AMC, JB ii) Implementation: JB, AMC, PK, BW, SJ, AD, AJD, KA, BMM, HV, IA, BW, PH iii) Prepared main manuscript text: JB and AMC iv)Making of SOP and intellectual inputs: CM, AMC, DL, JB, JL v) Data cleaning and analysis: SC, MM, SP vi) Reviewed and refined the article: All authors have read and approved the submission of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toJoyita Banerjee or AB Dey.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Indian Council of Medical Research (2202–16741/F1) and collaborating institution, University of Southern California (UP-15-00684). Informed consent to take part in the study was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Banerjee, J., Chutani, A.M., McEvoy, C. et al. Methodological considerations of diet assessment of the older Indian population in the longitudinal aging study in India—Harmonised Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia (LASI-DAD).BMC Public Health 25, 3661 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9

- Received: 01 May 2025

- Accepted: 17 September 2025

- Published: 29 October 2025

- Version of record: 29 October 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-24970-9