Dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis (original) (raw)

Article summary

AI generated

Dyslipidemia is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, with its prevalence increasing globally, particularly in developing countries like Ethiopia, where lifestyle factors such as smoking and physical inactivity contribute to its rise. This systematic review and meta-analysis found that the overall prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia is 56.60%, highlighting strong associations with insufficient physical activity, smoking, and chronic alcohol consumption, thereby underscoring the urgent need for targeted public health interventions.

This is an AI-generated summary, check important information.

Abstract

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, with its prevalence steadily rising in both developed and developing nations. An unhealthy lifestyle significantly contributes to the development of dyslipidemia, with smoking being a well-known risk factor.

Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted across several databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, African Journals Online (AJOL), HINARI, and PubMed/MEDLINE. Articles published up until June 24, 2024, were considered for inclusion. Data extraction and organization were carried out using Microsoft Excel, while analysis was performed using STATA/MP 17.0. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). To analyze the pooled data, a weighted inverse variance random effects model with a 95% confidence interval was applied. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochrane’s I2 statistics, and Egger’s test was conducted to detect potential publication bias. The association between dyslipidemia and its associated factors was examined using the log odds ratio, with a p-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 44 articles involving 12,395 participants were included. The overall pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia was 56.60% (95% CI 50.40–62.80). Dyslipidemia was observed across various population groups, with notable prevalence rates associated with different risk factors. Among individuals with insufficient physical activity, the prevalence was 30.12% (95% CI 22.53–37.70). In those who smoked cigarettes, it was observed in 6.81% (95% CI 4.27–9.34). Among chronic alcohol consumers, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was 15.75% (95% CI 9.65–21.86). Furthermore, 30.12% (95% CI 22.53–37.70) of dyslipidemia was reported among individuals with inadequate physical exercise.

Conclusions

The prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia was 56.60%, indicating a significant public health concern. The condition is particularly prevalent among individuals with insufficient physical activity, smoking habits, and chronic alcohol consumption, suggesting strong associations with these modifiable risk factors. To reduce dyslipidemia, public health initiatives should focus on promoting physical activity, anti-smoking campaigns, and educating on the risks of excessive alcohol use. Health professionals should also prioritize early detection and management in high-risk groups to reduce long-term cardiovascular risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Dyslipidemia refers to abnormal levels of lipids (cholesterol and/or fats) in the blood, indicating a disorder in lipoprotein metabolism, which can involve either overproduction or deficiency [1]. It is characterized by elevated levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) in the blood, factors that are preventable yet contribute to cardiovascular disease [2]. It poses a global public health challenge, with prevalence rates varying widely due to socioeconomic, cultural, and ethnic factors [3]. Although it is a modifiable risk factor for many chronic diseases, dyslipidemia continues to be a leading contributor to disease burden in both developed and developing countries [4]. Awareness, treatment, and management of dyslipidemia remain inadequate despite its high prevalence [5], affecting diverse populations, including children and adolescents [6].

Dyslipidemia is a significant risk factor for atherosclerosis and various cardiovascular diseases [7], with its prevalence rising steadily in both developed and developing nations [8]. It is notably common among individuals with conditions like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, HIV/AIDS, and psychiatric disorders, with a prevalence reaching 81.5%. There are significant gender differences in its occurrence, and key risk factors such as advanced age, obesity, and physical inactivity are strongly linked to the condition [9, 10]. Dyslipidemia is closely linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, particularly atherosclerosis, which accounted for more than 17 million deaths worldwide in 2015 [11].

An unhealthy lifestyle plays a crucial role in the development of dyslipidemia [12]. Among these, smoking is a well-known risk factor, associated with elevated triglyceride levels and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [13]. Compared to other factors affecting blood lipids, such as alcohol consumption, body mass index (BMI), and age, smoking has the most significant impact and is recognized as an independent risk factor for dyslipidemia [14]. Both current and former smokers have a higher odds ratio of developing dyslipidemia compared to non-smokers [13]. Alcohol consumption is another contributing factor to dyslipidemia [15]. It is also a leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide and has the potential to cause severe hypertriglyceridemia. This can occur either independently or in conjunction with other disorders related to lipid metabolism, exacerbating the overall risk to health [16].

Unhealthy diets and physical inactivity further increase the risk of dyslipidemia and contribute to cardiovascular diseases, including heart attacks and strokes [16]. Diet patterns rich in vegetables, fruits, seafood, legumes, soy products, and grains are inversely associated with hypercholesterolemia [17].

Despite the availability of screening tests, dyslipidemia remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Assessing health behavior patterns following diagnosis could improve lifestyle interventions for managing dyslipidemia [8]. Conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis is an important study as it provides a comprehensive evaluation of the prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia and identifies the key factors contributing to its rise. Given the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia, understanding the prevalence of lipid abnormalities can help inform targeted public health interventions. This review synthesizes existing data to offer precise estimates, ultimately guiding efforts to reduce its impact on the Ethiopian population and improve overall cardiovascular health. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia.

2 Methods

2.1 Reporting

The findings were reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Table S1) [18].

2.2 Databases and searching strategies

A comprehensive search was conducted across several databases, including Google Scholar, Web of Science, African Journals Online (AJOL), HINARI, and PubMed/MEDLINE, to identify studies on dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia. To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant articles, a range of search engines was employed, using terms related to dyslipidemia such as “dyslipidemia,” “lipid abnormality,” “abnormal lipid profile,” “hyperlipidemia,” “lipid levels,” “cholesterol,” “triglycerides,” “LDL,” “HDL,” and “lipid metabolism.” Prevalence-related keywords included “prevalence,” “incidence,” “proportion,” “magnitude,” “percentage,” “rate,” and “burden.” Terms for associated factors and conditions comprised “smoking,” “alcohol consumption,” “substance abuse,” “physical inactivity,” “sedentary lifestyle,” “obesity,” “diabetes,” “hypertension,” “age,” “gender,” “socioeconomic status,” “psychological stress,” “diet,” and “behavioral risk factors.” For Ethiopia, keywords such as “Ethiopia,” “Ethiopian population,” “Ethiopian adults,” and “sub-Saharan Africa” were used. The Boolean operators “AND” and "OR" were carefully applied to combine these terms and ensure a thorough literature search (Table 1).

Table 1 Searches on different databases to find articles conducted on dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia

2.3 Screening of studies

After collecting all relevant articles from various databases, they were exported to EndNote Reference Citation Manager software version 8 (Thomson Reuters, Stamford, CT, USA) [19]. The articles were then organized, and cleaned, and duplicates were removed. Four authors (AG, TA, MG, and BTA) independently assessed each article based on a predetermined inclusion criterion, evaluating titles, abstracts, relevance, and outcomes of interest. Any disagreements that arose during the screening process were resolved through discussion.

2.4 Data extraction

From the data extraction sheet, the first and last authors collected key information, including the names of the researchers, the publication year, the region where the studies were conducted, the sample size, and the prevalence of dyslipidemia in various populations. Factors such as cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and insufficient intake of fruits and vegetables were specifically considered for dyslipidemia prevalence. Furthermore, the odds ratios and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the identified associated factors were extracted to assess the strength and precision of these relationships. Any disagreements between authors during the selection process were resolved through consensus before proceeding with the analysis. The second and third authors review and verify the accuracy of the information. They carefully assessed the data to ensure it was correct and reliable, cross-checking sources to confirm that all details were accurate.

2.5 Eligibility of studies

Different studies that examine dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia were included. In terms of the population, only studies that involve Ethiopian populations from various regions within the country, including both urban and rural populations were considered. The study population consisted of patients with chronic diseases and the general adult population. Studies that explore factors associated with dyslipidemia, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, poor diet (like low fruit and vegetable intake), obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and socioeconomic status are eligible. Only studies that report on the prevalence, incidence, or odds of dyslipidemia, based on lipid profile abnormalities (such as elevated cholesterol, LDL, triglycerides, or low HDL levels) were included. Only studies published in English published until June 2024 were included. However, interventional studies, clinical trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, narrative reviews, qualitative studies, case reports, and policy statements were excluded. Additionally, articles without full text were excluded after two attempts to contact the corresponding author via email.

2.6 Measurement of the study results

The outcome variable of this study was dyslipidemia, which is measured using the criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) criteria of 2002. Then, to be dyslipidemia, patients should have at least one of the following lipid profiles in their serum/plasma: total cholesterol TC ⩾ 200 mg/dl, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-c ⩾ 130 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol HDL < 40 mg/dl and Triglyceride TGs ⩾ 150 mg/dl [20].

2.7 Quality assessment

Each author also independently assessed the quality of the articles using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cross-sectional studies [21]. The evaluation focused on the studies’ methodological quality, comparability, results, and statistical analysis. Studies that scored 7 out of 10 or higher were considered to be of high quality. High-quality studies, scoring 7 or above on the NOS, demonstrate strong methodology and minimal bias, while medium-quality studies, with scores between 4 and 6, show moderate rigor but some limitations in design or execution. Low-quality studies, scoring 3 or below, suffer from significant methodological flaws, such as poor participant selection or unreliable outcomes, leading to higher bias and reduced trustworthiness. Disagreements between the authors were resolved through discussion.

2.8 Data processing and analysis

Data extraction, editing, sorting, and cleaning were performed using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, after which the data was exported to STATA version 17 for analysis [22]. A weighted inverse variance random effects model with a 95% confidence interval was applied to pool the data [23]. The Cochrane Q-test and I2 statistic were used to assess the heterogeneity among the studies [24]. To identify the sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis, and sensitivity analysis were conducted. Additionally, Egger’s test was used to check for publication bias, and a funnel plot was generated to illustrate the distribution of the included studies [25]. To address any potential publication bias, a trim-and-fill analysis was performed. The association between dyslipidemia and its influencing factors was examined using a log odds ratio. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Result

3.1 Selection of articles

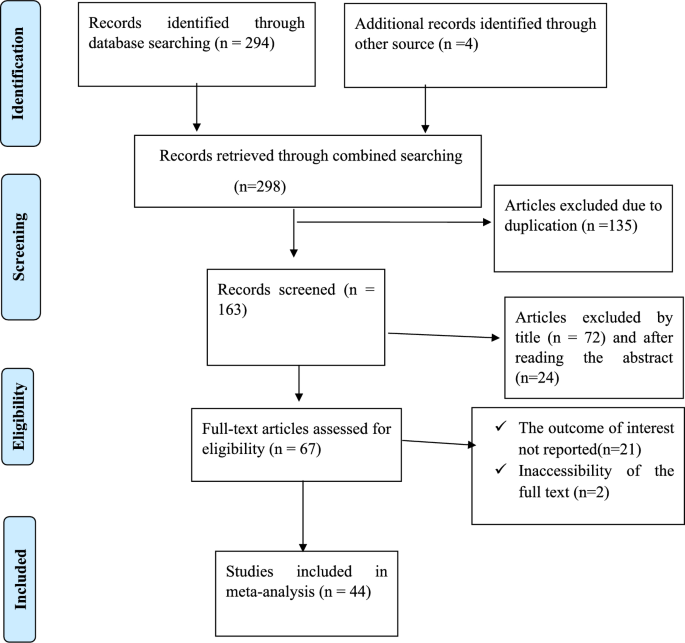

A comprehensive search across various databases using specific was conducted, and keywords yielded 298 articles. After removing duplicates, 135 studies remained. Out of these, 96 were excluded based on their titles and abstracts, 2 were excluded because the full text could not be obtained, and 21 were excluded for not reporting the outcome of interest. Ultimately, 44 full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria were selected for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

PRISMA flow chart diagram to select articles done on dyslipidemia in Ethiopia

3.2 Study characteristics

A total of 44 articles involving 12,395 participants were included to determine dyslipidemia and associated factors in Ethiopia. These studies were conducted across various regions of Ethiopia until June 2024. Specifically, 14 studies were conducted in the Oromia region [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], 10 in Addis Ababa [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], 10 in the Amhara region [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58], 7 in South Nation Nationalities and people’s region (SNNP) [59,60,61,62,63,64,65], and 3 in Tigray region [66,67,68]. Regarding patient types, 19 studies focused on diabetic patients, 12 on HIV/AIDS patients, 5 on the general adult population, 4 on cardiac patients, 2 on psychiatric patients, 2 on H. pylori-infected patients, and 1 on women using contraception. All included articles were cross-sectional in design, with sample sizes ranging from 48 to 1,180 participants (Table 2).

Table 2 The features of the included studies used to evaluate the prevalence of dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia

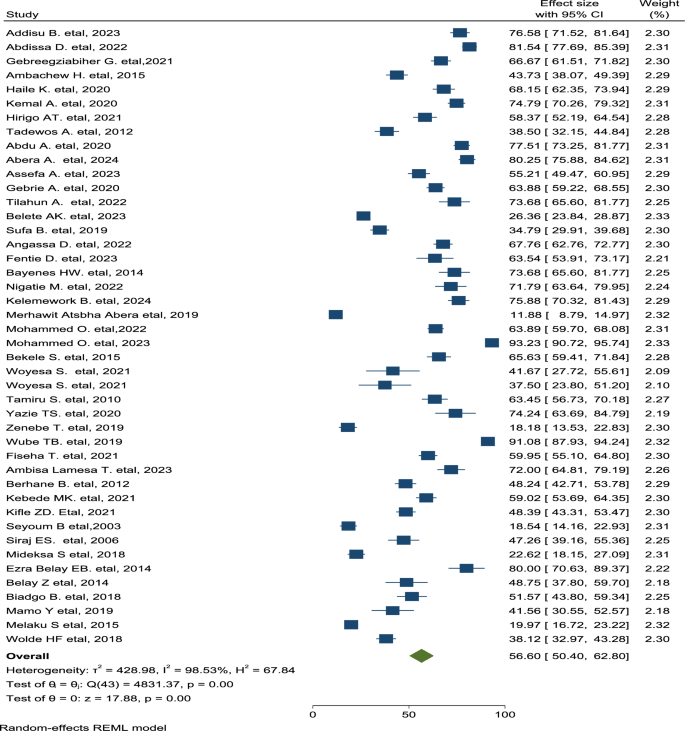

3.3 Prevalence of dyslipidemia

The overall pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia was 56.60% (95% CI 50.40–62.80) (Fig. 2). Dyslipidemia was observed among different population groups, including cigarette smoking at 6.81% (95% CI 4.27–9.34), chronic alcohol consumption at 15.75% (95% CI 9.65–21.86), inadequate physical exercise at 30.12% (95% CI 22.53–37.70), and insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption at 31.96% (95% CI 16.44–47.49).

Fig. 2

Forest plot displays the pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia

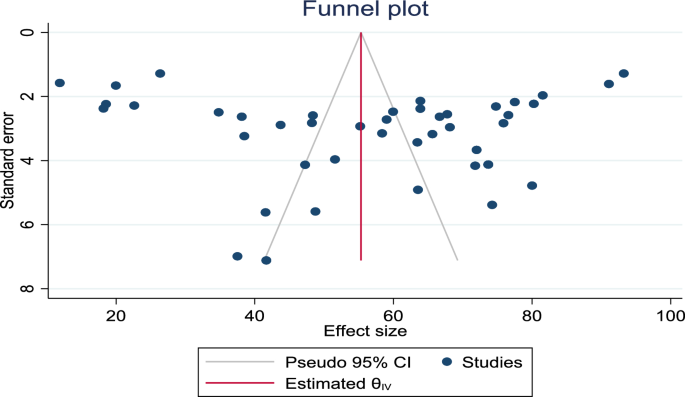

3.4 Heterogeneity and publication bias

Heterogeneity within the studies was detected (I2 = 98.53%, p < 0.001). A symmetrical distribution of the included articles was visible in the funnel plot and Egger’s test revealed a statistically insignificant result (p = 0.677), indicating the absence of publication bias (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Funnel plot with 95% confidence limits on the pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia

3.5 Sub-group analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed based on region and patient categories. Regionally, the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia associated with cigarette smoking was observed in the Amhara region, at 10.85% (95% CI 2.64–19.07). The highest prevalence of dyslipidemia associated with insufficient physical activity was found in the SNNP region, at 39.27% (95% CI 14.58–63.96). Similarly, the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia related to alcohol consumption was reported in Addis Ababa, at 27.4% (95% CI 22.82–32.14). Additionally, the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia associated with poor fruit and vegetable intake was recorded in the Oromia region, at 39.25% (95% CI 28.19–47.06) (Table 3).

Table 3 The pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia based on region categories in Ethiopia

In terms of patient categories, the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia due to inadequate physical activity was found among psychiatry patients, at 48.38% (95% CI 43.08–53.67). Among smokers, dyslipidemia was most prevalent in diabetic patients, at 11.48% (95% CI 6.19–16.76). Furthermore, dyslipidemia associated with poor fruit and vegetable consumption was more common in cardiac patients, at 34.20% (95% CI 17.60–50.80) (Table 4).

Table 4 The pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia based on population type in Ethiopia

3.6 Sensitivity analysis

A leave-one-point sensitivity analysis conducted using the random-effects model revealed that all points were estimates within the overall 95% confidence interval (50.40–62.80), indicating the absence of any influential study (Table 5).

Table 5 Sensitivity analysis of the pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia

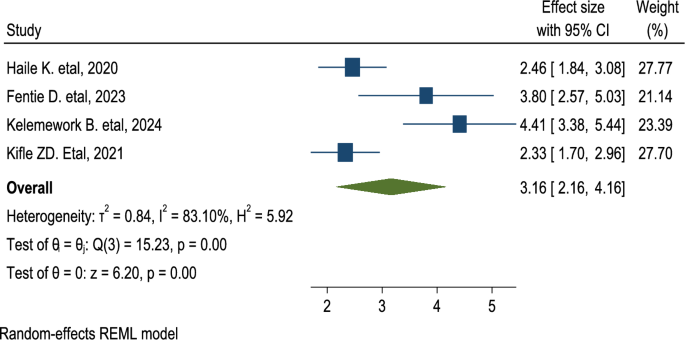

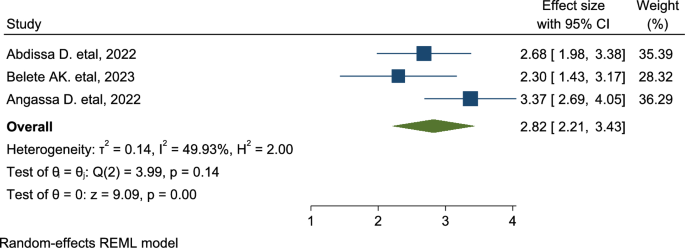

3.7 Factors associated with dyslipidemia

In this study, dyslipidemia was significantly associated with the level of physical activity and alcohol consumption. Consequently, participants who had poor physical activity behavior were 3.16 times more likely to have dyslipidemia than those who had regular physical exercise: (AOR = 3.16; CI 2.16–4.16) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, participants who are chronic alcohol drinkers were 2.82 times more likely to have dyslipidemia than their counterparts: (AOR = 2.82; 2.21–3.43) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4

The overall pooled odds ratio of the association between poor physical activity behavior and dyslipidemia in Ethiopia

Fig. 5

The overall pooled odds ratio of the association between alcohol consumption behavior and dyslipidemia in Ethiopia

4 Discussion

In this review, the overall pooled prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia was 56.60% (95% CI 50.40–62.80), with significant variations observed across different groups, including individuals with inadequate physical activity (30.12%), cigarette smokers (6.81%), chronic alcohol consumers (15.75%), and those with insufficient fruit and vegetable intake (31.96%). The highest prevalence of dyslipidemia among cigarette smokers was found in the Amhara region (10.85%), while the highest rate associated with inadequate physical activity was in the SNNP region (39.27%). For alcohol consumption, Addis Ababa had the highest prevalence (27.4%), and the highest prevalence related to insufficient fruit and vegetable intake was observed in Oromia (39.25%). In terms of patient categories, psychiatry patients with low physical activity had the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia (48.38%), diabetic smokers had the highest prevalence (11.48%), and cardiac patients with poor dietary habits had the highest prevalence (34.20%).

The prevalence of dyslipidemia in this study is higher than in studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, 40% [69], Jourdan, 44.3% [70], and China, 20.33% [71]. The potential reason for this variation might be the difference in the study settings. In Ethiopia, many chronically ill patients are often not diagnosed early, which may lead to a higher prevalence of undiagnosed or poorly managed conditions. Additionally, there is a difference in the diagnostic approaches used for chronic diseases in Ethiopia compared to other countries. Limited access to healthcare facilities, differences in medical infrastructure, and varying diagnostic protocols may contribute to the higher reported rates of dyslipidemia in the Ethiopian population. These factors could result in a delay in early detection and intervention, exacerbating the health outcomes in individuals with chronic illnesses.

The current finding is also inconsistent with the findings of studies done in Nigeria, 58.9% [72] and China, 19.2% [73]. This variation may result from differences in diagnostic approaches and study designs. This study is a systematic review and meta-analyses, which contribute to a broader understanding of dyslipidemia’s prevalence and impact in different contexts. In 2000, the Global Burden of Disease Study highlighted dyslipidemia as a significant contributor to Ethiopia’s health burden, particularly related to cardiovascular diseases. While specific prevalence rates were not provided, dyslipidemia was identified as a key risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality from heart disease and stroke in the country [74].

Based on region, the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia related to inadequate physical exercise was observed in studies from the SNNP region. This higher prevalence may be attributed to the fact that a significant portion of participants from the SNNP region were diabetic patients, who are at a higher risk for dyslipidemia compared to other groups [63, 64]. Similarly, the highest prevalence of dyslipidemia was observed in studies involving psychiatric patients, followed by diabetic patients. This may be attributed to the fact that many psychiatric disorders and their treatments have a notable effect on lipid metabolism. Furthermore, psychiatric patients often have unhealthy eating habits, engage in little physical activity, and lead more sedentary lifestyles. Likewise, in individuals with diabetes, insulin resistance causes an increase in the production of very low-density lipoprotein and a decrease in the clearance of triglycerides from the bloodstream, both of which contribute to dyslipidemia. Additionally, high blood sugar levels can interfere with lipid metabolism, leading to higher triglyceride levels [75].

Dyslipidemia was significantly associated with levels of physical exercise and alcohol consumption. Chronic alcohol drinkers were 2.82 times more likely to develop dyslipidemia compared to non-drinkers. This is because, chronic alcohol abuse impacts nearly every organ system, leading to severe conditions such as chronic liver disease, which in turn causes significant hypertriglyceridemia and disturbances in lipid metabolism [16]. Additionally, participants who had poor physical exercise behavior were 3.16 times more likely to have dyslipidemia than those who had regular physical exercise. The reason behind this is that poor physical exercise causes an abnormal fat distribution that leads to obesity [39].

4.1 Strengths and limitations of the study

A comprehensive national review of the literature with a clear focus on different populations and conditions of patients, the use of robust statistical methods to analyze pooled data, detailed meta-regression, and subgroup analysis to identify sources of heterogeneity, and the treatment of publication bias were the strengths of the study. However, significant heterogeneity among included studies, which could affect the reliability of pooled estimates, limited studies conducted in Ethiopia, which may not be generalizable to other settings, and the absence of a registered protocol in PROSPERO, which is a common practice for systematic reviews, which may affect the transparency and reproducibility of the review process, were the limitations of the study.

5 Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of dyslipidemia in Ethiopia, revealing a high overall prevalence, with significant associations with factors such as insufficient physical activity, cigarette smoking, chronic alcohol consumption, and inadequate fruit and vegetable intake. The findings underscore the regional and patient category differences in prevalence, highlighting the need for targeted interventions in specific populations like psychiatric and diabetic patients. The study also emphasizes the critical role of physical activity and alcohol consumption in the development of dyslipidemia. Given these insights, future research should focus on exploring effective strategies for preventing and managing dyslipidemia, particularly in high-risk groups, and on understanding the broader socio-economic and cultural factors that may contribute to these lifestyle behaviors. Further studies should also aim to assess the long-term impact of lifestyle modifications on dyslipidemia management, with a focus on developing region-specific public health policies and interventions.

Availability of data and materials

All related data have been presented within the manuscript. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available upon request from the authors.

Abbreviations

AIDS:

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

AJOL:

African Journals Online

AOR:

Adjusted Odds Ratio

BMI:

Body Mass Index

CI:

Confidence Interval

HIV:

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

NOS:

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

PRISMA:

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

SNNP:

South Nation Nationalities and People

DM:

Diabetes Mellitus

References

- Wajpeyi SM. Analysis of etiological factors of dyslipidemia case-control study. Int J Ayurvedic Med. 2020;11(1):92–7.

Article Google Scholar - Vaillant-Roussel H, Cadwallader J-S. Everyone under statin?: coll natl generalistes enseignants 3, rue parmentier, montreuil sous bois…; 2012. p. 188.

- Qi L, Ding X, Tang W, Li Q, Mao D, Wang Y. Prevalence and risk factors associated with dyslipidemia in Chongqing, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(10):13455–65.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang M, Deng Q, Wang L, Huang Z, Zhou M, Li Y, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and achievement of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol targets in Chinese adults: a nationally representative survey of 163,641 adults. Int J Cardiol. 2018;260:196–203.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yan L, Xu MT, Yuan L, Chen B, Xu ZR, Guo QH, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and its control in type 2 diabetes: a multicenter study in endocrinology clinics of China. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(1):150–60.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Elmaoğulları S, Tepe D, Uçaktürk SA, Kara FK, Demirel F. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated factors in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2015;7(3):228.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lin C-F, Chang Y-H, Chien S-C, Lin Y-H, Yeh H-Y. Epidemiology of dyslipidemia in the Asia Pacific region. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12(1):2–6.

Article Google Scholar - Cho IY, Park HY, Lee K, Bae WK, Jung SY, Ju HJ, et al. Association between the awareness of dyslipidemia and health behavior for control of lipid levels among Korean adults with dyslipidemia. Korean J Family Med. 2017;38(2):64.

Article Google Scholar - Alzaheb RA, Altemani AH. Prevalence and associated factors of dyslipidemia among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:4033–40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ali N, Kathak RR, Fariha KA, Taher A, Islam F. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and its associated factors among university academic staff and students in Bangladesh. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):366.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Agongo G, Nonterah EA, Debpuur C, Amenga-Etego L, Ali S, Oduro A, et al. The burden of dyslipidemia and factors associated with lipid levels among adults in rural northern Ghana: an AWI-Gen sub-study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11): e0206326.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li L, Ouyang F, He J, Qiu D, Luo D, Xiao S. Associations of socioeconomic status and healthy lifestyle with incidence of dyslipidemia: a prospective Chinese Governmental Employee Cohort Study. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 878126.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jeong W. Association between dual smoking and dyslipidemia in South Korean adults. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(7): e0270577.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tan X, Jiao G, Ren Y, Gao X, Ding Y, Wang X, et al. Relationship between smoking and dyslipidemia in western Chinese elderly males. J Clin Lab Anal. 2008;22(3):159–63.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Latourte A, Bardin T, Clerson P, Ea HK, Flipo RM, Richette P. Dyslipidemia, alcohol consumption, and obesity as main factors associated with poor control of urate levels in patients receiving urate-lowering therapy. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(6):918–24.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chowdhury I. Alcohol and dyslipidemia. In: Alcohol, nutrition, and health consequences. Humana Press; 2013. p. 329–39.

Chapter Google Scholar - Lin L-Y, Hsu C-Y, Lee H-A, Wang W-H, Kurniawan AL, Chao JCJ. Dietary patterns about components of dyslipidemia and fasting plasma glucose in adults with dyslipidemia and elevated fasting plasma glucose in Taiwan. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):845.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group* t. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bramer WM, Milic J, Mast F. Reviewing retrieved references for inclusion in systematic reviews using EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc JMLA. 2017;105(1):84.

PubMed Google Scholar - Expert Panel on Detection E. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on the detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–97.

Article Google Scholar - Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses, vol. 2. 1st ed. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. p. 1–12.

Google Scholar - Heß S. Randomization inference with Stata: a guide and software. Stand Genomic Sci. 2017;17(3):630–51.

Google Scholar - Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:1–9.

Article Google Scholar - Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Addisu B, Bekele S, Wube TB, Hirigo AT, Cheneke W. Dyslipidemia and its associated factors among adult cardiac patients at Ambo University referral hospital, Oromia region, west Ethiopia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):321.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Abdissa D, Hirpa D. Dyslipidemia and its associated factors among adult diabetes outpatients in West Shewa zone public hospitals, Ethiopia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):39.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Haile K, Timerga A. Dyslipidemia and its associated risk factors among adult type-2 diabetic patients at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:4589–97.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Abdu A, Cheneke W, Adem M, Belete R, Getachew A. Dyslipidemia and associated factors among patients suspected to have Helicobacter pylori infection at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma, Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:311–21.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sufa B, Abebe G, Cheneke W. Dyslipidemia and associated factors among women using hormonal contraceptives in Harar town. Eastern Ethiopia BMC research notes. 2019;12:1–7.

Google Scholar - Angassa D, Solomon S, Seid A. Factors associated with dyslipidemia and its prevalence among Awash wine factory employees, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):22.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fentie D, Yibabie S. Magnitude and associated factors of dyslipidemia among patients with severe mental illness in dire Dawa, Ethiopia: neglected public health concern. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):298.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Woyesa S, Mamo A, Mekonnen Z, Abebe G, Gudina EK, Milkesa T. Lipid and lipoprotein profile in HIV-infected and non-infected diabetic patients: a comparative cross-sectional study design, Southwest Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS-Res Palliat Care. 2021;13:1119–26.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tamiru S, Alemseged F. Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among diabetic patients in southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010;20(2):121–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zenebe T, Merga H, Habte E. A community-based cross-sectional study of the magnitude of dysglycemia and associated factors in Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Diabetes Dev Countries. 2019;39:749–55.

Article Google Scholar - Ambisa Lamesa T, Getachew Mamo A, Arega Berihun G, Alemu Kebede R, Bekele Lemesa E, Cheneke GW. Dyslipidemia and nutritional status of HIV-infected children and adolescents on antiretroviral treatment at the comprehensive Chronic Care and Training Center of Jimma Medical Center. HIV/AIDS Res Palliat Care. 2023;15:537–47.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Berhane T, Yami A, Alemseged F, Yemane T, Hamza L, Kassim M, et al. Prevalence of lipodystrophy and metabolic syndrome among HIV positive individuals on Highly Active Anti-Retroviral treatment in Jimma, South West Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13(1):43.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mamo Y, Bekele F, Nigussie T, Zewudie A. Determinants of poor glycemic control among adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma zone, southwest Ethiopia: a case-control study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019;19:1–11.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kemal A, Teshome MS, Ahmed M, Molla M, Malik T, Mohammed J, et al. Dyslipidemia and associated factors among adult patients on antiretroviral therapy in armed force comprehensive and specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS-Res Palliat Care. 2020;12:221–31.

Article Google Scholar - Assefa A, Abiye AA, Tadesse TA, Woldu M. Prevalence and factors associated with dyslipidemia among people living with HIV/AIDS on follow-up care at a tertiary care hospital in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2023;15:93–102.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bayenes HW, Ahmed MK, Shenkute TY, Ayenew YA, Bimerew LG. Prevalence and predictors of dyslipidemia on HAART and HAART naive HIV positive persons in defense hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(5):303.

Article Google Scholar - Mohammed O, Kassaw M, Fekadu E, Bikila D, Getahun T, Challa F, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia among school-age children and adolescents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Lab Phys. 2022;14(04):377–83.

CAS Google Scholar - Yazie TS. Dyslipidemia and associated factors in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-based regimen among human immunodeficiency virus-infected Ethiopian patients: a hospital-based observational prospective cohort study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2020;12:245–55.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Belay Z, Daniel S, Tedla K, Gnanasekaran N. Impairment of liver function tests and lipid profiles in type 2 diabetic patients treated at the diabetic center in Tikur Anbessa Specialized Teaching Hospital (Tasth), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Diabetes Metab. 2014;5(454):2.

Google Scholar - Seyoum B, Abdulkadir J, Berhanu P, Feleke Y, Mengistu Z, Worku Y, et al. Analysis of serum lipids and lipoproteins in Ethiopian diabetic patients. Ethiop Med J. 2003;41(1):1–8.

PubMed Google Scholar - Siraj ES, Seyoum B, Saenz C, Abdulkadir J. Lipid and lipoprotein profiles in Ethiopian patients with diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2006;55(6):706–10.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Melaku S, Enquselassie F, Shibeshi W. Assessment of glycaemic, lipid and blood pressure control among diabetic patients in Yekatit 12 Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Pharm J. 2016;31(2):131–40.

Article Google Scholar - Ezra Belay EB, Daniel Seifu DS, Wondwossen Amogne WA, Kelemu Tilahun Kibret KTK. Lipid profile derangements among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults receiving first-line anti-retroviral therapy in Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study; 2014.

- Gebrie A, Sisay M, Gebru T. Dyslipidemia in HIV/AIDS infected patients on follow up at referral hospitals of Northwest Ethiopia: a laboratory-based cross-sectional study. Obesity Medicine. 2020;18: 100217.

Article Google Scholar - Tilahun A, Chekol E, Teklemaryam AB, Agidew MM, Tilahun Z, Admassu FT, et al. Prevalence and predictors of dyslipidemia among HAART treated and HAART naive HIV positive clients attending Debre Tabor Hospital, Debre Tabor, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2022;8(11): e11342.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Belete AK, Kassaw AT, Yirsaw BG, Taye BA, Ambaw SN, Mekonnen BA, et al. Prevalence of hypercholesterolemia and awareness of risk factors, prevention, and management among adults visiting referral hospital in Ethiopia. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2023;19:181–91.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nigatie M, Melak T, Asmelash D, Worede A. Dyslipidemia and its associated factors among Helicobacter pylori-infected patients attending at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Gondar, north-west Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022;15:1481–91.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mohammed O, Alemayehu E, Ebrahim E, Fiseha M, Gedefie A, Ali A, et al. Atherogenic dyslipidemia and associated risk factors among hypertensive patients of five health facilities in Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(2): e0277185.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fiseha T, Alemu W, Dereje H, Tamir Z, Gebreweld A. Prevalence of dyslipidemia among HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in North Shewa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(4): e0250328.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kebede WM, Gizachew KD, Mulu GB. Prevalence and risk factors of dyslipidemia among type 2 diabetes patients at a referral hospital, North Eastern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2021;31(6):1267–76.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kifle ZD, Alehegn AA, Adugna M, Bayleyegn B. Prevalence and predictors of dyslipidemia among hypertensive patients in Lumame Primary Hospital, Amhara, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Metab Open. 2021;11: 100108.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Biadgo B, Melak T, Ambachew S, Baynes HW, Limenih MA, Jaleta KN, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at a tertiary hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(5):645–54.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wolde HF, Atsedeweyen A, Jember A, Awoke T, Mequanent M, Tsegaye AT, et al. Predictors of vascular complications among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at University of Gondar Referral Hospital: a retrospective follow-up study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2018;18:1–8.

Article Google Scholar - Ambachew H, Shimelis T, Lemma K. Dyslipidemia among diabetic patients in Southern Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. J Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;6(4):19–24.

Article Google Scholar - Hirigo AT, Teshome T, Abera Gitore W, Worku E. Prevalence and associated factors of dyslipidemia among psychiatric patients on antipsychotic treatment at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. Nutr Metab Insights. 2021;14:11786388211016842.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tadewos A, Addis Z, Ambachew H, Banerjee S. Prevalence of dyslipidemia among HIV-infected patients using first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy in Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional comparative group study. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9:1–8.

Article Google Scholar - Abera A, Worede A, Hirigo AT, Alemayehu R, Ambachew S. Dyslipidemia and associated factors among adult cardiac patients: a hospital-based comparative cross-sectional study. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):237.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kelemework B, Woubshet K, Tadesse SA, Eshetu B, Geleta D, Ketema W. The Burden of Dyslipidemia and Determinant Factors Among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2024;17:825–32.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wube TB, Begashaw TA, Hirigo AT. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and its correlation with anthropometric and blood pressure variables among type-2 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;11(1):10–7.

Article Google Scholar - Bekele S, Yohannes T, Mohammed AE. Dyslipidemia and associated factors among diabetic patients attending Durame General Hospital in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2017;10:265–71.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gebreegziabiher G, Belachew T, Mehari K, Tamiru D. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated risk factors among adult residents of Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2): e0243103.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Abera MA, Gebregziabher T, Tesfay H, Alemayehu M. Factors associated with the occurrence of hypertension and dyslipidemia among diabetic patients attending the diabetes clinic of Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia. East African J Health Sci. 2019;1(1):3-16.

- Mideksa S, Ambachew S, Biadgo B, Baynes HW. Glycemic control and its associated factors among diabetes BioMed Research International 11mellitus patients at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Mekelle-Ethiopia. Adipocyte. 2018; 7(3): 197–203. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad.

- Al-Hassan YT, Fabella EL, Estrella E, Aatif M. Prevalence and determinants of dyslipidemia: data from a Saudi University Clinic. Open Public Health J. 2018;11(1):416–24.

Article Google Scholar - Abujbara M, Batieha A, Khader Y, Jaddou H, El-Khateeb M, Ajlouni K. The prevalence of dyslipidemia among Jordanians. J Lipids. 2018;2018(1):6298739.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yang F, Ma Q, Ma B, Jing W, Liu J, Guo M, et al. Dyslipidemia prevalence and trends among adult mental disorder inpatients in Beijing, 2005–2018: a longitudinal observational study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;57: 102583.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Akintunde AA, Ayodele EO, Akinwusi OP, Opadijo GO. Dyslipidemia among newly diagnosed hypertensives: pattern and clinical correlates. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(5):403–7.

PubMed Google Scholar - Yu S, Yang H, Guo X, Zhang X, Zheng L, Sun Y. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated factors among the hypertensive population from rural Northeast China. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1–9.

Article Google Scholar - Murray CJL, et al. The Global Burden of Disease 2000 Project: The State of the Art. The Lancet. 2002;359(9302):2059–72.

Google Scholar - Wahlbeck K, et al. Depression and cardiovascular diseases: a review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(5):448–56.

Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

Addisu Getie, Temesgen Ayenew, Mihretie Gedfew & Baye Tsegaye Amlak

Authors

- Addisu Getie

- Temesgen Ayenew

- Mihretie Gedfew

- Baye Tsegaye Amlak

Contributions

AG designed the study, designed and ran the literature search and methodology. All authors (AG, TA, MG, and BTA) acquired data, screened records, extracted data, assessed the eligibility of the studies, and assessed the risk of bias. AG did the statistical analysis and wrote the report. All authors provided critical conceptual input, edited the manuscript, and critically reviewed the report. Finally, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toAddisu Getie.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

12982_2025_589_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Material 1. Table S1: The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist for reporting findings

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Getie, A., Ayenew, T., Gedfew, M. et al. Dyslipidemia and its associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Discov Public Health 22, 232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-025-00589-4

- Received: 18 January 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published: 07 May 2025

- Version of record: 07 May 2025

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-025-00589-4