Disappearing act: decay of uniform resource locators in health care management journals (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objectives:

This study examines the problem of decay of uniform resource locators (URLs) in health care management journals and seeks to determine whether continued availability at a given URL relates to the date of publication, the type of resource, or the top-level URL domain.

Methods:

The authors determined the availability of web-based resources cited in articles published in five source journals from 2002 to 2004. The data were analyzed using correlation, chi-square, and descriptive statistics. Attempts were made to locate the unavailable resources.

Results:

After checking twice, 49.3% of the original 2,011 cited resources could not be located at the cited URL. The older the article, the more likely that URLs in the reference list of that article were inactive (r = −0.62, P<0.001, n = 1,968). There was no difference in availability across resource types (χ2 = 5.28, df = 2, P = 0.07, n = 1,786). Whether an URL was active varied by top-level domain (χ2 = 14.92, df = 4, P = 0.00, n = 1,786).

Conclusions:

URL decay is a serious problem in health care management journals. In addition to using website archiving tools like WebCite, publishers should require authors to both keep copies of Internet-based information they used and deposit copies of data with the publishers.

Highlights

- The number of decayed uniform resource locators (URLs) per journal title over a 3-year period ranged from 720 (Health Affairs) to 25 (Health Care Management Review).

- The domain extensions with the largest percentage of inactive URLS were the .com (53%, n = 266), .gov (51.2%, n = 685), and .org (47.8%, n = 730) extensions.

- The Wayback Machine of the Internet Archive found almost 60% of the inactive URLs (n = 992), and almost 50% of the inactive URLs were located using the websites' search functions.

Implications

- Librarians must be prepared to use several different search engines to help patrons locate cited web-based resources.

- Disciplines that depend heavily on .gov, .com, and .org sites will suffer the most from the effects of URL decay.

- Because sites such as Internet Archive and WebCite will remove archived web pages at the owners' request, authors should not depend on these utilities as the sole archives for web-based information.

INTRODUCTION

Article citations serve many purposes. Writers use references to credit other authors' ideas. Citation analysis is used to study trends in a particular field. Researchers use references to find original or additional sources of information.

Locating cited Internet-based resources can be difficult because the original documents may have been removed from the web or their content may have been revised or altered. Other Internet resources may still exist, but their addresses—uniform resource locators (URLs)—may have changed, rendering cited URLs obsolete. Additional resources may be hosted behind members-only interfaces, where they may be impossible or expensive to obtain. Koehler believes that because of these characteristics, “web documents are not the same thing as published and immutable works. Nor do they disappear the very moment they are uttered or broadcast. The WWW represents a third model that coexists between the recorded and the unrecorded.” He continues, “Because it is a new medium, we have not yet fully identified the dynamics of its behavior” [1].

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

A number of studies exist of resource inaccessibility at cited URLs, known variously as URL decay [2] or link rot [3]. Koehler produced three now-classic longitudinal studies of a sample of web pages [1,4,5] and Bar-Ilan and Peritz examined informatics web pages [6]. Examples of other studies include, but are not limited to, examinations of print and online bibliographies of Internet pages [3,7,8], undergraduate student papers [9–12], conference papers [13,14], online public access catalogs (OPACs) [15], and MEDLINE citations [16–18]. Many researchers have studied references in scholarly journal articles. Fields examined include, but are not limited to, biomedicine [2, 19–26], biomedical informatics [27], business [28], communications [29,30], computer science [31], ecology [32], law [33], and library and information science [34–38]. Another set of articles looks at trends in journals in several fields [39–43].

These studies, which used varying methodologies and timeframes, reported widely differing percentages of found URLs. Sellitto finds that 96% of citations in conference papers were available within a year of publication, for the highest success rate [13]. Tyler and McNeil, who examined website bibliographies, reported the lowest rate of successful access, finding only 20% of URLs 7 years after publication [3]. Among studies of scholarly journal citations, Zhang reported the highest percentage of found URLs, locating 69% after 1 year [38]. Thorp and Brown found the lowest percentage, locating 39% of citations between 1 and 6 years old [25].

The authors became interested in examining link decay in the health care management literature while completing a study to map the literature of health care management as part of the Mapping the Literature of Allied Health Project of the Medical Library Association's Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section [44,45]. At that time, one of the authors of this paper was liaison to the Southern Illinois University Carbondale (SIUC) Department of Health Care Management and another was liaison to the SIUC School of Business. We examined the reference lists of research articles from Health Affairs, Health Care Management Review, Health Services Research, Journal of Healthcare Management, and Medical Care Research and Review from 2002 to 2004. That study focuses on documenting the number of resources according to format type—journals, government documents, Internet resources, and miscellaneous—rather than on information delivery sources. We found just over 1,000 citations to nongovernmental and non-journal Internet resources over the 3-year period and a little over double that number (n = 2,011) if government and journal websites were included.

We also noted that the rate of link decay in the health care management literature had never been documented. We postulated that, based on the number of cited Internet resources and the likely existence of URL decay, researchers and the librarians who serve them might encounter difficulties in locating cited Internet-based resources. Therefore, it is important and useful to document the existence and amount of URL decay in the health care management literature. For example, health care management research, especially if it is focused on policy issues or health services research, relies on government information. A high rate of URL decay could severely hamper government resources researchers in this field.

Our research questions included:

- What is the overall rate of URL decay for Internet-based references in health care management journals?

- Does this rate vary when the time elapsed since publication, format type, or top-level domain is examined?

- What percentage of missing resources can be located with commonly used tools and methods?

- How does the rate of decay and ability to locate resources compare to other studies?

- What methods and resources are available to maintain access to cited Internet-based resources?

METHODOLOGY

A total of 2,011 web-based resources were extracted from the reference lists, and the accessibility of each resource at the listed URL was tallied in March 2007. This information was recorded in a Microsoft Access database. Information about a cited resource (source journal, issue date, type of resource, URL, URL domain extension, availability) was entered only once per article. If the resource was found at its original site and the date or edition of the content matched the cited date or edition, the URL was considered active for the purposes of this study. The resource was also considered found if the researchers were redirected to the new location of the item, because locating the resource at any URL would satisfy most patrons.

In addition to “File Not Found” errors, a resource was considered not found if the cited edition was not located or if material with the cited date could not be found. With the exception of subscription journal articles, if access to a resource was blocked by the site, the resource was considered not found because the researchers could not determine the availability of the cited content. Because some sites might have been only temporarily unavailable, inactive links were rechecked after five months. If they were still inactive at that time, they were recorded as inactive.

To determine whether the availability of a resource varied over time, the publication date of source journal issues was also recorded. A regression analysis was run studying the percentage of active URLs at the specified months. Some reference lists contained unique resources that had identical URLs. For example, some authors referred to several sub-pages of a site but cited the top domain as the URL for each. These specific duplicates (same journal, same issue, same URL, same availability status) were removed before running the regression analysis (n = 1,968). For this test, resources with duplicate URLs that were not from the same article were kept in the database, because the content of the represented websites could have been revised or changed over time.

We also examined the effects of specific resource types and domain extensions on the availability of the Internet-based resources in our project. The resource types included journals, government documents, and miscellaneous. As defined in our previous study, the journal format included all newspaper, journal, and government-published serials [44]. The government document classification contained all non-journal resources published by international (e.g., United Nations), national, regional, and local governments. The miscellaneous category included all other types of resources.

The top-level domain was recorded as .com, .edu, .gov, .net, or .org. URLs from sites not using this nomenclature were assigned to one of these categories, in some cases by visiting the page and examining the purpose of the site. Chi-square analyses were done relating format type to availability and domain extension type to availability. Any remaining duplicate URLs were removed prior to running these analyses (n = 1,786).

Attempts were made to locate all of the resources (n = 992) whose URLs were unavailable. Resources with duplicate URLs were included. The content of a site might have changed over time, and some unique pages had the same URL. Except for subscription journal articles, a resource was considered found if the cited edition or material containing the cited content date was found. If an abstract for a subscription journal article was located, the resource was considered found because patrons could obtain the material using interlibrary loan.

A variety of methods were employed to locate missing resources. Information in the reference itself was used, and the article text was examined for more information if necessary. We did not stop if we located a resource using one tool or method but tried all methods on each inactive URL. The site's search function was used if available. The original URL was “shaved.” That is, starting on the far right-hand side of the URL, the directories were deleted one at a time to see if higher-level directories would provide access to the data.

Google and the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine were used to try to locate missing information. Google was selected because it is well known and heavily used by patrons. The Internet Archive's Wayback Machine was used because the Internet Archive's software crawls websites repeatedly over time, so several versions of a page are often available [46]. Other studies have used these two tools to attempt to locate web resources [30,35,36].

RESULTS

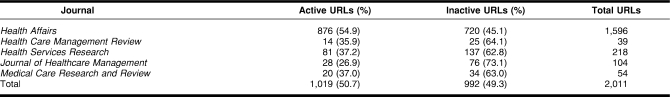

When first checked, over half (1,060) of the 2,011 URLs were inactive at the published site. After rechecking, this number decreased to 992, or 49.3% (Table 1), with 1,019 active URLs. Two journals, Health Affairs and Health Services Research, had the highest number of web-based references and the highest total number of inactive URLS but also had the lowest percentages of inactive links when compared to Medical Care Research & Review and the 2 health business-oriented journals.

Table 1.

Number of active and inactive uniform resource locators (URLs) by journal title

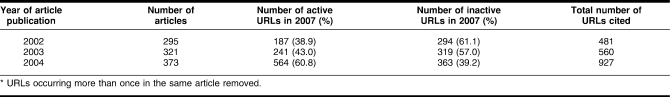

Table 2 gives the results without the first group of duplicates. The percentage of URLs increased by 16.4% between 2002 and 2003 and by 65.5% between 2003 and 2004, for an overall increase of 92.7% between 2002 and 2004 (Table 2). Most of the increase came from Health Affairs, which contained citations with 359 URLs in 2002, 460 URLs in 2003, and 743 URLs in 2004, for a 107% increase overall. This might be due to Health Affairs starting its “Web Exclusives,” journal articles published only online, in 2001.

Table 2.

Number and percent of active and inactive URLs in 2007 by year of publication (n = 1,968)*

The percentage of inactive URLs ranged from 39.2% for articles published in 2004 to 61.1% for articles published in 2002. There were no studies of URL decay in health care management journals for comparison, but in 2001, Griffin examined the related field of business [27]. He checked articles published in Business Communication Quarterly in 1998, 1999, and 2000 and found that found that 47% of URLs in the reference lists were inaccessible after 2 years, 49% after 3 years, and 66% after 4 years.

Not surprisingly, there was a negative correlation between the percentage of active URLs and the publication age of the citations. That is, as the age of the citations increased, the percentage of active URLs tended to decrease (r = −0.68, P<0.001, n = 1,968) (Table 2).

Health Affairs moved to the HighWire Press platform in the fall of 2003 [47]. There were 228 citations to articles published in the online version of Health Affairs or to the Health Affairs website after the first set of duplicates (same journal, same issue, same URL, same availability status) were removed. All but 2 of the 125 active URLs were from articles published in 2004. The 2 active cited URLs, from articles published in September 2002 and February 2003, were the URL for the journal's home page, which remained unchanged at the new platform. Because of the large number of citations to Health Affairs, we decided to repeat the regression analysis excluding those citations to see if the change in platform had unduly affected the results. There was still a negative correlation between the percentage of available URLs and the publication age of the citations in the new analysis (r = −0.58, P<0.001, n = 1,740).

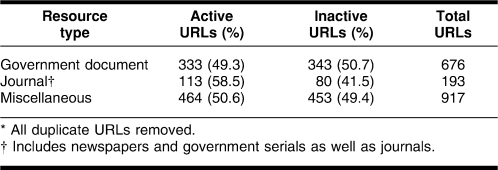

Our data did not indicate any difference in availability across resource types (journal, government document, miscellaneous) (χ2 = 5.28, df = 2, P = 0.07, n = 1,786) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number and percent of active URLs by resource type (n = 1,786)*

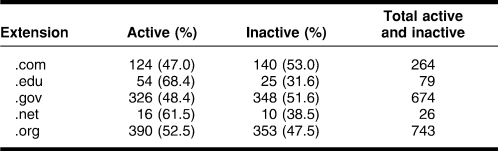

Whether or not an URL was active varied by domain (χ2 = 14.91, df = 4, P = 0.00, n = 1,786) (Table 4). The highest percentage of inactive URLs was found in the .com top-level domain, followed by the .gov and the .org domain. The type most likely to be active was the .edu domain.

Table 4.

Number and percent of active and inactive URLs by domain extension (n = 1,786)

The result for the .gov top-level domain was surprising and differs from the results of many other studies (e.g., Dimitrova and Bugeja's study of communication journals [29]). However, some studies have found high percentages of inactive URLS with .gov extensions. Both Casserly and Bird in 2003 (library and information science journals) [35] and Strader and Hamill (URLs in OPACs) [14] found that URLs with the .gov top-level domain were the most likely to not be found. It should be noted that in addition to the .gov top-level domain, fifteen of the government resource types had .org top-level domains.

The most successful tool for finding the originally cited content at the 992 inactive URLs was using the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine, which located 59.8% (593 items), followed by Google, which had links to 48.8% (484) of the missing material. In their 2007 study of references in communication journals, Dimitrova and Bugeja found 53.5% (n = 733) of missing cited resources via the Wayback Machine but only 27.4% of the missing items using Google [30]. In their initial and follow-up studies of library and information science journals respectively, Casserly and Bird found that they were able to retrieve 49.3% (n = 213) and 58.6% (n = 295) of resources not located at the cited URL using the Wayback Machine, and they found 25.4% (n = 213) and 30.7% (n = 300) of missing resources using Google [35,36].

We located 39.0% (387) of the missing web resources using the site search function at the original domain (or new domain if redirected). It should be noted that almost 12.0% (116/992) of the inactive web resources did not have a site search function or the host domain of the URL could not be found. Of the 992 missing items, 17.5% (174) could not be found using any of the 4 methods or tools. Using the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine found 249 unique items (that is, resources not found by the other tools or methods), while using Google found 56, shaving the URL found 12, and using the site search function found 8.

LIMITATIONS

The study looked at five health care management or health services journals over a limited period of time. Results should not be generalized to all journals in this field at all times.

No single search engine indexes every resource on the web. Therefore, using only Google limited our chances of retrieving a page. We used Google <http://www.google.com> rather than Google US Government Search <http://www.google.com/unclesam> for government documents. Using the specialty site might have located more US government documents [48]. We assumed for the purposes of this study that subscription journal articles did not change once they have been posted to the web. Therefore, we did not check the content of journal articles to see if changes had been made. In reality, online journal articles might have different content over time: URLs in reference lists might be updated, information might be amended, and so on.

Although our data did not indicate any difference in availability across resource types (Table 3), an anonymous reviewer suggested that there might have been differences if we had distinguished between types of periodicals (subscription, open access, newspaper, etc.).

DISCUSSION

Some fields of study may be more prone to the effects of URL decay than others, particularly if many of the scholarly materials utilized are available on the Internet and norms permit the use of Internet documents in scholarly materials.

The effect of inactive links can vary within journals in the same discipline, depending on the authors' reliance on web-based information. Health Affairs, a health policy journal, had the lowest percentage of inactive links, but it had the largest total number of links, perhaps reflecting a reliance on web-based government resources. It also had the largest number of inactive links. The sheer number of URLs magnifies the problem of URL decay for the readers of articles in a journal such as Health Affairs compared to journals such as Health Care Management Review, whose authors cited only thirty-nine web resources.

Each search tool, when used on its own, found unique items. In addition, no one search tool is perfect, including those used in this study. Google does not index dynamic pages or pages and sites that include robots.txt coding to prevent crawling. In addition, a site's or page's rank in Google search results depends on the number of other pages that link to it [48]. The Internet Archive has its own limitations. One can only search the Wayback Machine for URLs based on hypertext transfer protocol (http). However, nine of the decayed URLs used file transfer protocol (ftp), so we could not test these using the Wayback Machine. The Internet Archive also has difficulty archiving certain types of dynamic pages, including pages that contain “forms, JavaScript, or other elements that require interaction with the originating host” (e.g., server side image maps). It does not archive pages that are not linked to other pages or password-protected pages. In addition, the Internet Archive will withdraw material if the owners of a site requests it, and it will not crawl and archive a site if the site owner so requests [46]. The results of this study, taken in combination with the realization of the limitations of search instruments, suggest that when searching for resources with inactive links, it is best to use a variety of tools.

The effects of inactive links are less severe if the missing resources are subscription journal articles. Articles can usually be obtained via interlibrary loan, and the content is probably the least likely to change of the 3 resource types. However, journal articles made up only 10.8% of the cited resource types and 9.1% of the missing URLs (n = 1,786).

One of the major causes of inactive links is website reorganization. As previously mentioned, most of the citations to active links in the online version of Health Affairs were to articles published after the journal changed platforms. However, we noted changes in domain names, which seemed to indicate site reorganizations, for both organization and government websites.

Government information is increasingly being shifted to the Internet, often without a print backup copy, and government websites are frequently being reorganized [49,50]. Problems locating government information are exacerbated by the fact that much of this information is not accessible to commercial search engines [48]. As noted earlier, although many studies have found that URLs with government domain extensions were among the most stable of the domain types, some recent studies have found that this is no longer the case [14,35]. Our study provides further evidence that government websites have become increasingly vulnerable to URL decay as reorganization, document removal, and content change have occurred. One possible explanation for this change is the natural evolution of websites. Layne and Lee suggest that government websites proceed through four stages of development [51], while Gil-Garcia and Pardo expand the number of stages to seven [52].

Other reasons are possible. The articles we examined for our study were probably prepared up to one to two years before publication (i.e., from 2000 to 2003). Several events occurred during this period that may have precipitated change and affected URLs published in these articles, including the focus on the Year 2000 bug that might have limited time to work on other technical issues and a change in US presidential administration.

Strader and Hamill, who examined links in OPAC records in fall 2002 and early 2003, speculated that the reason that they found a larger percentage of inactive links for US government sites than many earlier studies was that sites might have been reorganized and changed to enhance security after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks [14]. It should be noted that the E-Government Act of 2002 was passed during this period. The act, which took effect on April 17, 2003, expanded initiatives to improve security of government information, protect citizens' privacy, improve the delivery of government information, and promote data integration [53]. Implementation of any of these initiatives might have led to changes to government websites.

If one accepts the evidence of this and other studies, URL decay is a problem. Researchers and publishers, however, may minimize the magnitude of the issue, because they assume that search engines such as Google are able to locate resources at their new URLs. These groups must remember that such tools do not index every document that is on the Internet and cannot locate items that have been removed from the web. Tools such as the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine <http://www.archive.org/web/web.php> and WebCite <http://www.webcitation.org> may be able to provide a snapshot of the content of a site at a particular time. But even these do not contain every document that is or was available on the Internet.

This problem of URL decay seems likely to become more acute as more publishing outlets shift from a print to an electronic focus. For example, the Christian Science Monitor will stop producing daily print editions in 2009 and will publish most of its stories on its website. The Monitor claims that it is the first major national newspaper to move away from print [54]. Mirroring this shift in the mass media, an increasing number of academic journals publish material only online or produce online editions along with print versions. Librarians feel pressure from users to shift to online access to journals and other information. The percentage of citations in undergraduate papers that point to URLs has been increasing [9–12].

Several other solutions have been proposed to deal with the problem of dead links and/or altered content. Some remedies depend on content providers:

- DOIs are unique alphanumeric codes assigned to content that can be used in place of URLs to retrieve content. There is a fee charged for registering a DOI. DOIs are generally assigned by the content creator or publisher [55]. Several journals as well as the current editions of the AMA Manual of Style: A Guide for Authors and Editors [56], the APA style Guide to Electronic Resources [57], and the Chicago Manual of Style [58] require using a DOI if one is available instead of an URL. However, the fee may prove to be a barrier to use. Even if an article's DOI remains stable, this fact does not guarantee that the content of the document will remain unchanged.

- Uniform resource names (URNs) identify the content of a web document unrelated to its location. They commonly use other unique content identifiers like international standard book numbers (ISBNs) and international standard serial numbers (ISSNs) to identify content. Document creators must include URNs in web documents [59].

- PURLs are persistent uniform resource locators [60]. Anyone who registers for OCLC's free PURL resolver can create PURLs. When the URL changes, someone has to manually update the PURL to the new URL. The most effective use would be for content creators to create and manage PURLs and authors to link to those PURLs. In other words, for this to be effective, a large number of content creators would have to use PURLs and maintain the PURLs they create.

- Robust hyperlinks use a “lexical signature” appended to the URL to enhance document retrieval. The lexical signature can be submitted to site search engines to find the content even if the URL has changed. There has been limited adoption of this idea since it was first proposed and tested in 2000 by Phelps and Wilensky [61].

- Institutional repositories offer some promise for continued access to academic research and publications. Institutional repositories provide a permanent home on the web for scholarly work produced at sponsoring colleges and universities. Authors can upload copies of article preprints and copies of peer-reviewed articles for which they have retained copyright. This approach is limited by the copyright policies of journal publishers and the willingness of authors to submit their work to the repository. In addition, authors are sometimes permitted to remove their works from a repository. In this study, one online resource originally located in one institutional repository was found in another institutional repository, possibly because the author had changed affiliations.

- Archiving web resources is another answer. The Internet Archive has already been discussed. Google's cache can be used to recover some older versions of pages indexed by Google. This requires that the original document be indexed by the search giant and that the user enters the necessary search terms to retrieve it. The Google cache retains only one copy of a document made the previous time Google indexed the page [62].

Many feel that responsibility for archiving web content used in an article rests with the authors and/or publishers of articles using that content. Dellavalle and his coauthors “believe that the best current solution to improve access to Internet references is to require capture and submission of all Internet information at the time of manuscript consideration” [21]. This, however, puts the burden on the publisher to archive the information. Authors could be required to archive the material themselves, either by saving print copies or by archiving copies of cited electronic materials on their personal computers.

A tool such as Zotero <http://www.zotero.org>, a citation-management extension developed for the Mozilla Firefox browser, allows authors to automate the process of saving citations. Zotero has an advantage over simply saving electronic documents to a hard drive in that it can automatically generate and format bibliographies in a number of scholarly formats [63]. However, while Zotero and similar resources allow the author to keep copies of cited materials, they do not help readers find the cited pages. Other solutions are available:

- Furl <http://www.furl.net> is a web-based social bookmarking service that allows users to save copies of documents to a cache for later use [64]. Authors will have access to the documents as long as Furl keeps them, but this solution will not help readers find the documents.

- WebCite <http://www.webcitation.org> is an on-demand Internet archiving service. Citing authors can request that the online document they cite be archived by WebCite. These archived documents are stored on WebCite's servers and can be linked to by authors or searched by readers. WebCite preserves a copy of the page at the time that it was viewed by the citer. WebCite plans on assigning DOIs for some content in its collection starting in 2008 [65]. A number of journals now require authors to archive cited web-based material in WebCite [66]. Like the Internet Archive, WebCite cannot archive all types of dynamic pages. And, as with the Internet Archive, WebCite's owners will remove archived sites at the request of the authors of the original pages and will not crawl, cache, or archive a site if the coding of the site so dictates.

Of these solutions, one of the most promising is WebCite, because it allows both creators and readers to archive documents for free and keep the archived items in a place where potential readers can recover the documents. All of the other options are limited because they either can only be performed by the creator or limit copies to the authors' personal computers. However, as noted above, WebCite has its own limitations. Therefore, the best solution at this time is to require archiving copies of all Internet resources used on WebCite for easier access for readers, but also to require authors to retain their own copies. Editors should require authors to submit copies of all Internet resources used when they submit their articles.

CONCLUSION

The number of inactive links was unevenly distributed in the five journals examined in this study. However, effects of URL decay and missing editions of content remain important, no matter how many web resources are cited. Inactive links will always be with us. Readers must have access to resources used in order to validate the conclusions reached by authors. In the interests of scholarship, authors should be prepared to present copies of the Internet resources used, just as they must be prepared to show other forms of data.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Roberta Reeves, Instructional Support Services, Library Affairs, Southern Illinois University Carbondale (SIUC), and Ji-Hye Park, formerly of Library Affairs and currently at Kookmin University, Korea, for their assistance with the statistical analysis, and Mark Watson, Information Services, Library Affairs, SIUC, for reviewing the article. Mary Taylor, AHIP, thanks Library Affairs and the Research and Publications Committee of Library Affairs, SIUC, for research leave for data collection. We also thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Contributor Information

Cassie Wagner, Assistant Professor and Web Development Librarian, Instructional Support Services, Morris Library, Library Affairs, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, MC 6632, 605 Agriculture Drive, Carbondale, IL 62901 cwagner@lib.siu.edu.

Meseret D. Gebremichael, Public Services Librarian, Holman Library, McKendree University, 701 College Road, Lebanon, IL 62254-1299 mdgebremichael@mckendree.edu.

Mary K. Taylor, Associate Professor and Natural Sciences Librarian mtaylor@lib.siu.edu.

Michael J. Soltys, Applications Programmer, Instructional Support Services; Morris Library, Library Affairs, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, MC 6632, 605 Agriculture Drive, Carbondale, IL 62901 msoltys@lib.siu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koehler W. An analysis of web page and web site constancy and permanence. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1999 Feb;50(2):162–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wren J.D., Johnson K.R., Crockett D.M., Heilig L.F., Schilling L.M., Dellavalle R.P. Uniform resource locator decay in dermatology journals: author attitudes and preservation practices. Arch Dermatol. 2006 Sep;142(9):1147–52. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.9.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyler D.C., McNeil B. Librarians and link rot: a comparative analysis with some methodological considerations. Portal-Libr Acad. 2003;3(4):615–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koehler W. Web page change and persistence—a four-year longitudinal study. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2002 Feb;53(2):162–71. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koehler W. A longitudinal study of web pages continued: a consideration of document persistence. Inf Res [Internet] 2004 Jan;9(2) paper 174 [cited 18 Dec 2008]. < http://www.informationr.net/ir/9-2/paper174.html>.

- 6.Bar-Ilan J., Peritz B.C. Evolution, continuity, and disappearance of documents on a specific topic on the web: a longitudinal study of “informetrics.”. J Am Soc Inf Sci Tec. 2004;55(11):980–90. doi: 10.1002/asi.20049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor M.K., Hudson D. “Linkrot” and the usefulness of web site bibliographies. Ref User Serv Q. 2000 Spring;39(3):273–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitchens J.D., Mosley P.A. Error 404: or, what is the shelf-life of printed internet guides? Libr Collect Acquis Tech Serv. 2000 Winter;24(4):467–78. doi: 10.1016/S1464-9055(00)00178-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis P.M., Cohen S.A. The effect of the web on undergraduate citation behavior 1996–1999. J Am Soc Inf Sci Tec. 2001;52(4):309–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis P.M. The effect of the web on undergraduate citation behavior: a 2000 update. Coll Res Libr. 2002;63(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis P.M. Effect of the web on undergraduate citation behavior: guiding student scholarship in a networked age. Portal-Libr Acad. 2003;3(1):41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraus J.R. Citation patterns of advanced undergraduate students in biology, 2000–2002. Sci Technol Libr. 2002;22(3/4):161–79. doi: 10.1300/J122v22n03_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellitto C. The impact of impermanent web-located citations: a study of 123 scholarly conference publications. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2005 May;56(7):695–703. doi: 10.1002/asi.20159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bugeja M., Dimitrova D.V. Exploring the half-life of Internet footnotes. Iowa J Commun. 2005 Spring;37(1):77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strader C.R., Hamill F.D. Rotten but not forgotten: weeding and maintenance of URLs for electronic resources in The Ohio State University online catalog. Ser Libr. 2007;53(1/2):163–77. doi: 10.1300/J123v53n01_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wren J.D. 404 not found: the stability and persistence of URLs published in MEDLINE. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(5):668–72. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aronsky D., Madani S., Carnevale R.J., Duda S., Feyder M.T. The prevalence and inaccessibility of Internet references in the biomedical literature at the time of publication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007 Mar–Apr;14(2):232–4. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wren J.D. URL decay in MEDLINE—a 4-year follow-up study. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(11):1381–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson N., Tarczy-Hornoch P., Bumgarner R. On the persistence of supplementary resources in biomedical publications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(1):260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung J. Vanishing websites are the weakest link. Nature. 2001 Nov 1;414(6859):15. doi: 10.1038/35102257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crichlow R., Winbush N., Davies S. Digital information archiving policies in high-impact medical and scientific periodicals. JAMA. 2004 Dec 8;292(22):2723–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellavalle R.P., Hester E.J., Heilig L.F., Drake A.L., Kuntzman J.W., Graber M., Schilling L.M. Information science. going, going, gone: lost Internet references. Science. 2003 Oct 31;302(5646):787–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1088234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hester E.J., Heilig L.F., Drake A.L., Johnson K.R., Vu C.T., Schilling L.M., Dellavalle R.P. Internet citations in oncology journals: a vanishing resource? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004 Jun 16;96(12):969–70. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madani S., Carnevale R.J., Duda S., Feyder M., Aronsky D. Prevalence and inaccessibility of URLs in the biomedical literature. AMIA Annu Symp Proc [Internet] 2006 [cited 27 May 2008]. < http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgiartid1839732>. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Olfson E., Laurence J. Accessibility and longevity of Internet citations in a clinical AIDS journal. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005 Jan;19(1):5–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorp A.W., Brown L. Accessibility of Internet references in Annals of Emergency Medicine: is it time to require archiving? Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Aug;50(2):188–92, e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carnevale R.J. The life and death of death of URLS in five biomedical informatics journals. Int J Med Inform. 2007 Apr;76(4):269–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin F. 404 file not found: citing unstable web sources. Bus Commun Q. 2003 Jun;66(2):46–54. doi: 10.1177/108056990306600204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimitrova D.V., Bugeja M. Consider the source: predictors of online citation permanence in communication journals. Portal-Libr Acad. 2006 Jul;6(3):269–83. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimitrova D.V., Bugeja M. Raising the dead: recovery of decayed online citations [Internet]. Am Comm J. 2007 Summer;9(2) [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.acjournal.org/holdings/vol9/summer/articles/citations.html>.

- 31.Spinellis D. The decay and failures of web references. Commun ACM. 2003 Jan;46(1):71–7. doi: 10.1145/602421.602422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duda J.J., Camp R.J. Ecology in the information age: patterns of use and attrition rates of Internet-based citations in ESA journals, 1997–2005. Frontiers Ecol Environ. 2008;6(3):145–51. doi: 10.1890/070022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rumsey M. Runaway train: problems of permanence, accessibility, and stability in the use of web sources in law review citations. Law Libr J. 2002 Winter;94(1):27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benbow S.M.P. File not found: the changing problems of URLS for the World Wide Web. Internet Res. 1998;8(3):247–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casserly M.F., Bird J.E. Web citation availability: analysis and implications for scholarship. Coll Res Libr. 2003 Jul;64(4):300–17. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casserly M.F., Bird J.E. Web citation availability: a follow-up study. Libr Resour Tech Serv. 2008 Jan;52(1):42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goh D.H-L., Ng P.K. Link decay in leading information science journals. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2007 Jan;58(1):15–24. doi: 10.1002/asi20513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y. The impact of Internet-based electronic resources on formal scholarly communication in the area of library and information science: a citation analysis. J Inf Sci. 1998 Aug 24:241–54. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evangelos E., Trikalinos T.A., Ioannidis J.P.A. Unavailability of online supplementary scientific information from articles published in major journals. FASEB J. 2005 Dec;19(14):1943–4. doi: 10.1096/fj05-4784lsf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Germain C.A. URLs: uniform resource locators or unreliable resource locators. Coll Res Libr. 2000 Jul;61(4):359–65. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawrence S., Pennock D.M., Flake G.W., Krovetz R., Coetzee F.M., Glover E., Nielsen F.Å, Kruger A., Giles C.L. Persistence of web references in scientific research. Computer. 2001 Feb;34(2):26–31. doi: 10.1109/2.901164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta U. On the world wide web: where are you going, where have you been? Internet Ref Serv Q. 2000;5(1):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker A. Link rot: how the inaccessibility of electronic citations affects the quality of New Zealand scholarly literature [Internet] Whitireia Community Polytechnic; 2007. [cited 15 May 2008]. < http://www.coda.ac.nz/cgi/viewcontent.cgiarticle1000contextwhitireia_library_jo>. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor M.K., Gebremichael M.D., Wagner C.E. Mapping the literature of health care management. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007 Apr;95(2):e58–65. doi: 10.3163/1588-9439.95.2.E58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section, Medical Library Association. Mapping the literature of allied health: overview [Internet] Kent, OH: The Section; [rev. 30 Oct 2005; cited 24 Nov 2008]. < http://www.nahrs.mlanet.org/activity/mapping/alhealth/>. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Internet Archive. Frequently asked questions [Internet]. [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.archive.org/about/faqs.php>.

- 47.Goldstone G. 2008 Aug 5. Date of the move of Health Affairs to the Highwire Press platform. Telephone conversation with: Mary K. Taylor. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein B. Google and the search for federal government information. Against the Grain. 2008 Apr;20(2):30, 32, 34. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aldrich D., Bertot J.C., McClure C.R. E-government: initiatives, developments, and issues. Gov Inf Q. 2002;19(4):349–55. doi: 10.1016/S0740-624X(02)00130-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho A.T.K. Reinventing local governments and the e-government initiative. Public Adm Rev. 2002 Jul/Aug;62(4):434–44. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Layne K., Lee J. Developing fully functional e-government: a four stage model. Gov Inf Q. 2001;18:122–36. doi: 10.1016/S0740-624X(01)00066-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gil-Garcia J.R., Pardo T.A. E-government success factors: mapping practical tools to theoretical foundations. Gov Inf Q. 2005;22(2):187–216. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2005.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.E-government reauthorization act of 2007 (S.2321) [Internet]. 2002 [cited 23 Nov 2008]. < http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/zc110:S.2321:>.

- 54.Cook D. Monitor shifts from print to web-based strategy [Internet]. [rev. 28 Oct 2008; cited 18 Nov 2008]. < http://www.csmonitor.com/2008/1029/p25s01-usgn.html>.

- 55.International DOI Foundation. Welcome to the DOI system [Internet] The Foundation; [rev. 18 Sep 2008; cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.doi.org>. [Google Scholar]

- 56.AMA manual of style: a guide for authors and editors. 10th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Psychological Association. APA style guide to electronic references. Washington, DC: The Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chicago manual of style. 15th ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arms W., Daigle L., Daniel R., LaLiberte D., Mealling M., Moore K., Weibel S. Uniform resource names: a progress report. D-Lib Mag [Internet]; 1996 Feb;2. [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.dlib.org/dlib/february96/02arms.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Online Computer Library Center. PURLS [Internet] The Center; [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.purl.oclc.org>. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phelps T.A., Wilensky R. Robust hyperlinks and locations. D-Lib Mag [Internet]; 2002 Jul/Aug;6(7/8). [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.dlib.org/dlib/july00/wilensky/07wilensky.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Google web search help: search results page [Internet] Google; [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.google.com/support/bin/static.pypagesearchguides.htmlctxresults>. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Center for History and New Media, George Mason University. Zotero [Internet] Fairfax, VA: The Center; 2008. [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.zotero.org>. [Google Scholar]

- 64.LookSmart. Furl [Internet] New York, NY: Looksmart; 2008. [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.furl.net>. [Google Scholar]

- 65.WebCite. WebCite consortium members [Internet]. [cited 18 Sep 2008]. < http://www.webcitation.org/members/>.

- 66.WebCite. WebCite frequently asked questions [Internet]. [cited 24 Nov 2008]. < http://www.webcitation.org/faq/>.