Frontiers | Exploring Amino Acid Auxotrophy in Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 (original) (raw)

Introduction

The gut lumen contains a very complex mixture of compounds from alimentary and endogenous origins together with living microorganisms. The intestinal microbiota is metabolically active and plays a significant role in host physiology and metabolism (Hamer et al., 2012). The ability to metabolize peptides and amino acids is shared by a large number of bacteria ranging from saccharolytic bacteria to obligate amino acid fermenters present in gut microbiota (Davila et al., 2013). Peptides are the preferred substrates over free amino acids for many colonic bacteria, probably due to kinetic advantages of peptide uptake systems. Moreover, nitrogen source, such as amino acids, are fermented to short-chain fatty acids and organic acids, representing energy fuel for the colonic mucosa (Davila et al., 2013).

Milk proteins and peptides such as lactoferrin, lactoperoxidase, and lysozyme are reported to provide a non-immune defense against microbial infections (Schanbacher et al., 1997). In addition, they are known to stimulate growth of several members of the human infant microbiota such Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (Liepke et al., 2002; McCann et al., 2006). In this latter ecological context, the bacterial population is dominated by bifidobacteria, which remain a prominent component of the gut microbiota until weaning (Turroni et al., 2012a; Duranti et al., 2015; Underwood et al., 2015). Member of the genus Bifidobacterium are anaerobic microorganisms, typically resident in the gastro intestinal tract of mammals and insects (Lugli et al., 2014), where they are known to interact with their hosts using various genetic strategies (O’Connell Motherway et al., 2011; Fanning et al., 2012; Ventura et al., 2012; Turroni et al., 2014).

Among host-derived nutrients, milk proteins significantly influence the composition of the gut microbiota, supplying these microorganisms with nitrogen and amino acids (Liepke et al., 2002). Enhancement of (bifido)bacterial growth is frequently associated with milk proteins and the peptides that arise from the hydrolysis of these proteins (Nagpal et al., 2011; Lonnerdal, 2013).

Compared to carbon metabolism, for which a large body of scientific data is available (Pokusaeva et al., 2011; Marcobal et al., 2013), only very limited knowledge is available on the acquisition and assimilation processes that are used by members of the infant gut microbiota to retrieve nitrogen from the gut lumen (Liepke et al., 2002). For Gram positive bacteria, nitrogen metabolism has been investigated in Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (Liu et al., 2012), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Lebeer et al., 2007) and Bacillus sp. (Fisher, 1999; Even et al., 2006).

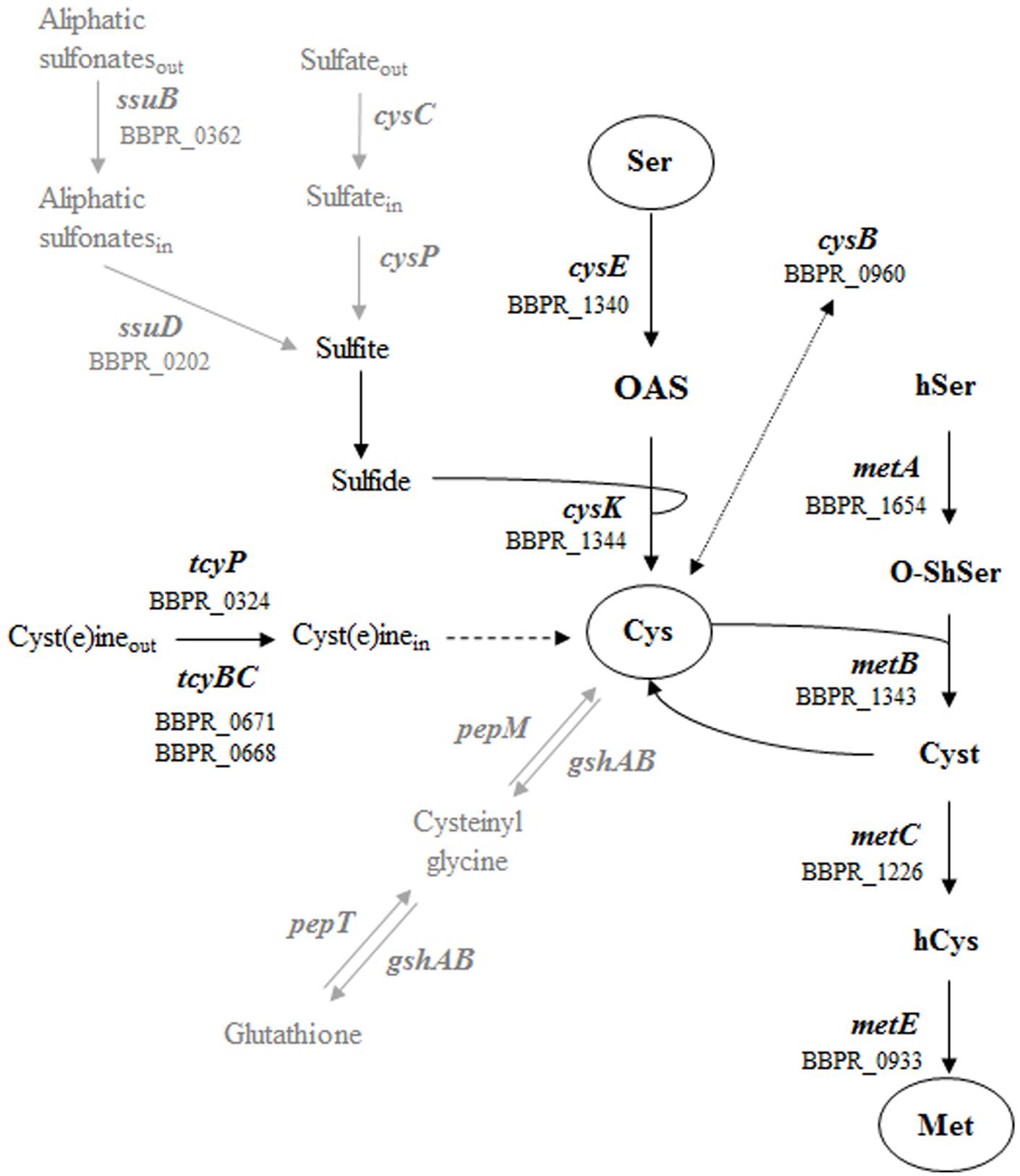

Recently, specific interest has been directed toward sulfur-containing amino acids and global control of cysteine and methionine metabolism in both Gram positive and negative bacteria, such as Lactococcus lactis, Salmonella sp., Vibrio fischeri and Clostridium perfringens (Fernandez et al., 2002; Andre et al., 2010; Alvarez et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2015). Cysteine biosynthesis is the key mechanism by which inorganic sulfur is reduced and incorporated into organic compounds (Kredich, 1992), where it plays an essential role in the formation of the catalytic sites of several enzymes, or protein folding and assembly via the formation of disulfide bonds (Mihara and Esaki, 2002). Sulfur-containing compounds that are used for the synthesis of cysteine and methionine are transported into the bacterial cell through different mechanisms: the first involves sulfate permease related to inorganic phosphate transporters (CysC) and then the reduction of sulfate to sulfide (Mansilla and de Mendoza, 2000) (Figure 1). The second involves aliphatic sulfonate ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (SsuBD) (van der Ploeg et al., 1998) and the subsequent conversion into sulfide by an FMNH monooxygenase (Figure 1). The following reaction of sulfide with _O_-acetyl-L-serine (OAS) results in cysteine synthesis by the action of an _O_-acetylserine thiol-lyase (Bogicevic et al., 2012). Alternatively, cysteine can be directly transported inside the cell by symporter proteins (TcyBCP) (Burguiere et al., 2004). Methionine biosynthesis is closely linked to cysteine production by the action of serine acetyltransferase, which uses cysteine and an _O_-acetylhomoserine to generate cystathionine, where the latter compound is then converted to homocysteine and methionine (Fernandez et al., 2002) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Schematic representation of the metabolic pathways for sulfur amino acid in Gram positive bacteria. The different ORFs of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 encoding the predicted enzymes are indicated. The metabolic steps present in Gram positive bacteria but absent in PRL2010 (sulfate assimilation and glutathione synthesis) are indicated by gray arrows. Molecule involved are reported as follow: serine Ser, _O_-acetyl-L-serine OAS, cysteine Cys, homoserine hSer, _O_-succinylhomoserine _O_-ShSer, cystathionine Cyst, homocysteine hCys and methionine Met.

In this study, in order to understand the role of the bifidobacterial population in the utilization of nitrogen available in the human gut, we evaluated the amino acid metabolism of the infant stool isolate B. bifidum PRL2010 (LMG S-28692), a bifidobacterial prototype for analysis of interactions between microbes and the intestinal mucosa (Turroni et al., 2013), by coupling physiological data on a chemically defined medium (CDM) with transcriptional analysis. Specific emphasis was placed on sulfur amino acids/metabolism of PRL2010 since these amino acids are particularly important for the bacterial cells of gut commensals in coping against gut related stresses (e.g., oxidative stress) (Even et al., 2006).

Furthermore, PRL2010 metabolism of complex substrates from milk such as casein hydrolysate and whey proteins was investigated.

Materials And Methods

Bacterial Strains and DNA Extraction

Bifidobacterial strains used in this study are reported in Table 1. Strains were grown anaerobically in de Man, Rogosa, Sharpe (MRS) medium (Scharlau, Spain), which was supplemented with 0.05% L-cysteine-HCl and incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Anaerobic conditions were achieved by the use of an anaerobic cabinet (Ruskin), in which the atmosphere consisted of 10% CO2, 80% N2, and 10% H2.

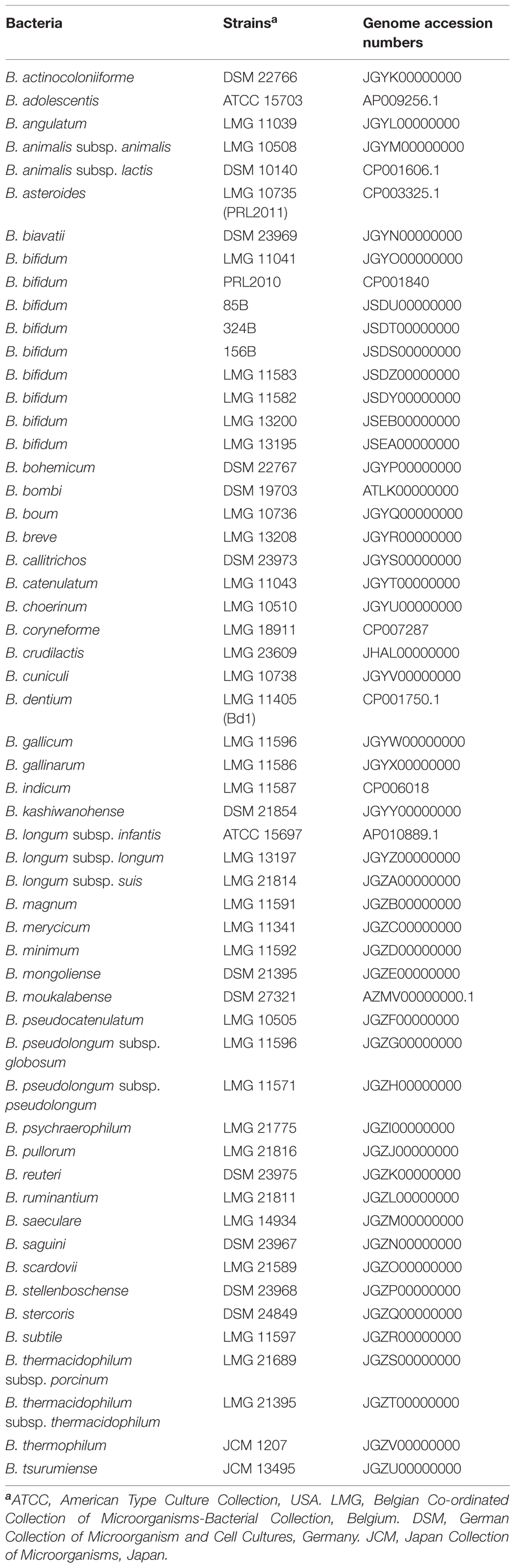

TABLE 1. Bifidobacterial strains used in this study.

Bifidobacterium CDM Development

For amino acid auxotrophy and prototrophy tests, a CDM was employed based on a previously described formulation (Petry et al., 2000; Cronin et al., 2012) for Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, with some modifications. Briefly, to the already reported CDM, 50 mg/l of guanine and 4.0 mg/l of thiamine was added. Several simple sugars were screened including glucose, fructose, galactose, lactose, ribose, xylose, fucose, mannose, and rhamnose. All carbohydrates were added at 2% (w/w). The medium was sterilized by filtration (0.22 μm). When the CDM was prepared without amino acids it is termed basal CDM (bCDM). All components of CDM were purchased from Sigma (USA).

Amino Acid and Nitrogen Growth Assay

Cell growth on CDM was monitored by measuring the optical density of cultures at 600 nm (OD 600) using a plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA). The plate reader was run in discontinuous mode, with absorbance readings performed after 24 h of incubation and preceded by 30 s of shaking at medium speed. Bacteria were cultivated in the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate, with each well containing a different amino acid, and incubated in an anaerobic cabinet.

For all growth tests, cells were recovered from an overnight MRS broth culture, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min in anaerobiosis, and washed with bCDM to remove protein and sugar residues. In each of the 96-wells of the microplate, 135 μl of medium was inoculated with 15 μl of washed cells diluted to OD 1.0 with bCDM, obtaining a final inoculum OD of 0.1. Wells were covered with 30 μl of sterile mineral oil in order to maintain anaerobic conditions. Cultures were grown in biologically independent triplicates and the resulting growth data were expressed as the means from these replicates.

Once it had been established that CDM supports bifidobacterial growth, amino acid assays were performed using CDM in which individual amino acids were omitted or with bCDM supplemented with 0.2 g/l of a particular amino acid. To understand amino acid metabolism and in particular the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids derived from complex substrates, bCDM was supplemented with 2–0.5% (w/w) of whey protein or casein hydrolysate (Sigma). To test the influence of reduced sulfur substrate instead cysteine to PRL2010 growth, 5 mM of reduced glutathione (Sigma) was added to bCDM formulation without any other amino acid (bCDM + Glut). To evaluate the utilization of source of sulfur and nitrogen available in the gut environment, 0.5 g/l of taurine was added to bCDM.

Identification of Genes Involved in Sulfur-containing Amino Acid Metabolism

The identification of genes involved in cysteine and methionine metabolism in PRL2010 and other B. bifidum strains was performed by using the BLASTP program (Gish and States, 1993). For the BLAST search, previously identified genes involved in sulfur metabolism of lactic acid bacteria were used (Liu et al., 2012). Twenty bp oligonucleotides for RT-qPCR experiments were manually designed on identified putative genes to obtain amplicons with a size ranging from 150 to 200 bp. Primers were checked with Primer Blast (Ye et al., 2012) and listed in Table 2.

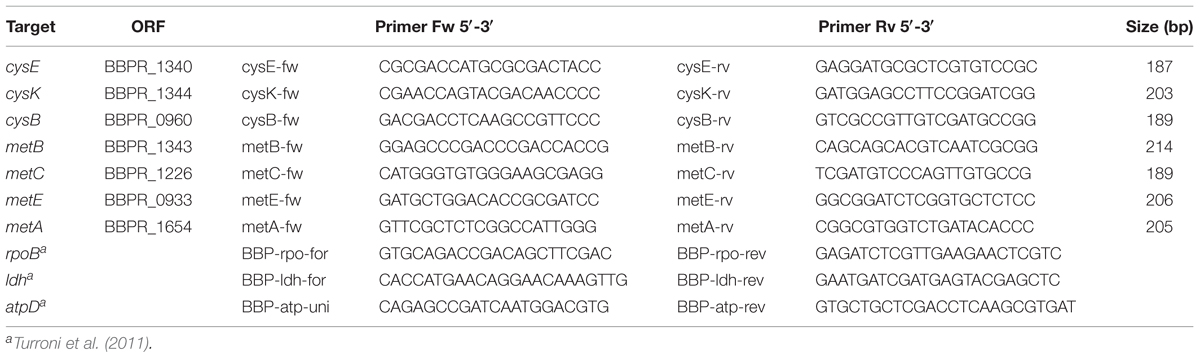

TABLE 2. Primers used for RT-qPCR experiments.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from PRL2010 cultures grown in CDM, bCDM supplemented with cysteine, or bCDM supplemented with cysteine and whey protein or casein hydrolysate (2% w/w). PRL2010 cells grown in MRS was used as a control condition. Cultures were grown in biologically independent triplicates. Cells were harvested by centrifugation step at 4000 ×g for 5′ at 4°C when cells had reached late exponential phase (OD values of 0.8–1.0, except for bCDM supplemented with glutathione where cells were harvested at OD 0.35). Cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen, UK) and mechanically lysed by inclusion of 0.1 mm zirconium–silica beads (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) and by subjecting the sample to three 2 min pulses at maximum speed in a bead beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) with intervals of 3 min on ice. RNA was extracted with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) as reported in the manufacturer’s instructions. Quality and integrity of the RNA was checked by Tape station 2200 (Agilent Technologies, USA) analysis and only samples displaying a RIN value above seven were used. RNA concentration and purity was then determined with a Picodrop microlitre Spectrophotometer (Picodrop). Reverse transcription to cDNA was performed with the iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad) using the following thermal cycle: 5 min at 25°C, 30 min at 42°C, 10 min at 45°C, 10 min at 50°C and 5 min at 85°C.

The mRNA expression levels of these genes were analyzed with SYBR green technology in quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using SoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Biorad) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCR was carried out according to the following cycle: initial hold at 96°C for 30 s and then 40 cycles at 96°C for 2 s and 60°C for 5 s. Gene expression was normalized relative to a housekeeping genes as previously described (Turroni et al., 2011) and reported in Table 2. The amount of template cDNA used for each sample was 12.5 ng.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance between means was analyzed using the two way ANOVA. Statistically different means were determined using the Bonferroni post hoc test at 5% (_P_-value < 0.05). Values are expressed as the means ± standard errors from three experiments. Statistical calculations were performed using the software program GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Development of a CDM for B. bifidum PRL2010

We modified the previously described CDM formulations (Petry et al., 2000; Cronin et al., 2012) based on the nutrient requirements of B. bifidum PRL2010. Several growth attempts on CDM minimal modifications (Petry et al., 2000; Cronin et al., 2012), i.e., where various compounds were omitted one after the other, allowed the identification of a number of components that were either essential or non-essential for growth of PRL2010 cells. Notably, folic acid and pyridoxal were eliminated from CDMPRL2010 composition, while guanine and thiamine were supplemented. When testing different sugars it was observed that PRL2010 exhibits the best growth performance with lactose, consistent with previous studies (Turroni et al., 2010, 2012b), and this sugar was therefore used for CDMPRL2010 formulation.

Evaluation of Amino Acids Auxotrophy and Prototrophy of PRL2010

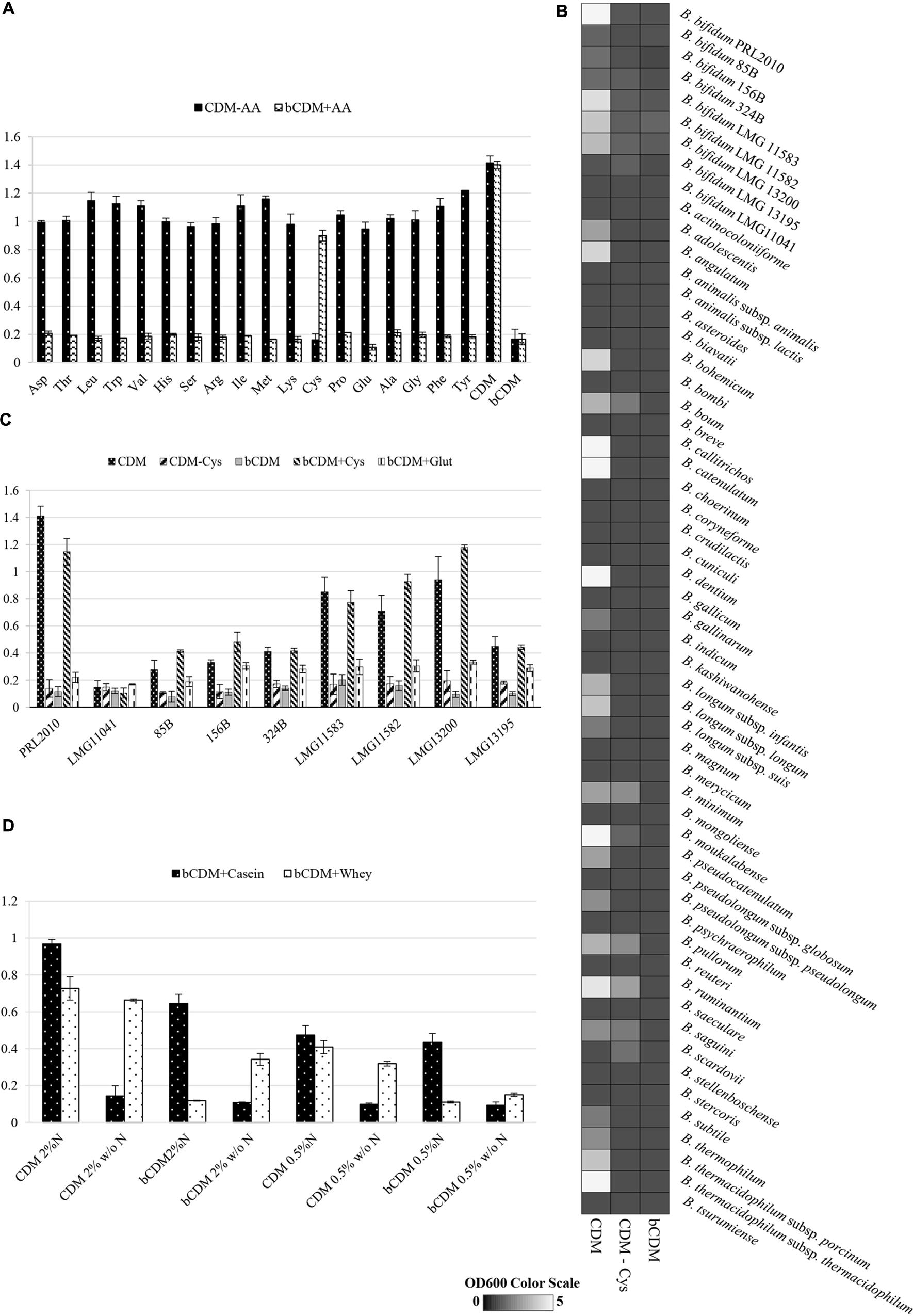

When PRL2010 cells were cultivated on CDMPRL2010, they exhibited reduced growth (OD600 value of 1.21 ± 0.3) compared to that observed when grown on a nutrient-rich medium such as MRS (OD600 value of 2.9 ± 0.2). In order to assess PRL2010 amino acid prototrophy/auxotrophy, growth experiments were performed using CDMPRL2010 where an individual amino acid had been omitted at time, and bCDMPRL2010 medium with the inclusion of one amino acid at time. The achieved growth yield was compared to that obtained for complete CDMPRL2010 or bCDMPRL2010 respectively (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2. Growth of B. bifidum strains. Growth was measured as the optical density of the medium at 600 nm (OD600). Cultures were grown in triplicates. (A) Reports the growth of B. bifidum PRL2010 in CDMPRL2010. In these tests, one amino acid at time was removed (CDM-AA) or supplied (bCDM + AA) to the medium. Amino acids are reported in the horizontal axis as follows: aspartic acid Asp, threonine Thr, leucine Leu, tryptophan Trp, valine Val, histidine His, serine Ser, arginine Arg, isoleucine Iso, methionine Met, lysine Lys, cysteine Cys, proline Pro, glutamine Gln, alanine Ala, glycine Gly, phenylalanine Phe and tyrosine Tyr. (B) Shows an heat map representing the growth performance of all of the type strains of the currently recognized 48 (sub)species belonging to the genus Bifidobacterium on CDMPRL2010, CDM-CysPRL2010 and bCDMPRL2010. The different shading represents the optical density reached by the various cultures. (C) Displays the growth of B. bifidum strains LMG11041, 85B, 156B, 324B, LMG11583, LMG11582 LMG13200 and LMG13195 in comparison with PRL2010 in CDMPRL2010, CDMPRL2010 without cysteine (CDM – Cys), basal CDMPRL2010 (bCDM), basal CDMPRL2010 with cysteine (bCDM + Cys) and basal CDMPRL2010 with glutathione (bCDM + Glut). (D) Illustrates the growth of B. bifidum PRL2010 in CDMPRL2010 supplemented with complex substrates like whey proteins or casein hydrolysate. For both substrates two concentration were tested, 0.5 and 2% (wt/wt). For every concentration was evaluated the presence of amino acid (CDM or bCDM) or other nitrogen sources (N or w/o N).

In both experiments, only when cysteine was removed or supplied to the medium a significant decrease or increase (ranging from four- to sixfold, P < 0.05) of the obtained growth yield was observed, respectively, suggesting that PRL2010 is auxotrophic for cysteine. Furthermore, PRL2010 seems unable to grow on sulfate as its sole sulfur source, such as when this strain is grown in bCDMPRL2010 (a medium that contains MnSO4, MgSO4, and FeSO4).

Another reducing compound, glutathione, was added to bCDMPRL2010 and only very limited growth was detected when PRL2010 cells were cultivated for 24 h (OD600 value of 0.31 ± 0.038). Furthermore, we decided to investigate if taurine, which is a common nitrogen and sulfur sources present in the gut environment (Carbonero et al., 2012) influence the growth yields of PRL2010. However, we did achieved any significant grow (OD600 = 0.10 ± 0.01) of PRL2010 when taurine was used as the unique nitrogen and sulfur sources.

Assessing Cysteine Auxotrophy of Members of the Genus Bifidobacterium

We further investigated the behavior of other strains belonging to the B. bifidum species (see Table 1), when cultivated under similar growth conditions (Figure 2B). These experiments showed that strains LMG11041, 156B, 85B, 324B, and LMG13195 were unable to grow on CDMPRL2010, (OD600 values ≤ 0.3) after 24 h of incubation (Figure 2B). The other B. bifidum strains investigated (i.e., LMG13200, LMG11582, and LMG11583) reached OD600 values of 0.7–0.9 and exhibited an identical auxotrophic behavior as PRL2010 for cysteine (Figure 2B).

Within the genus Bifidobacterium, the same auxotrophic behavior for cysteine appears to be widely distributed. In fact, of the currently recognized 48 (sub)species harboring the genus Bifidobacterium, only B. boum LMG10736, B. minimum LMG11592, B. pullorum LMG21816, B. ruminantium LMG21811, B. saguini DSM23967 and B. scardovii LMG21589 were shown to be able to grow in CDMPRL2010 without cysteine, though such strains reached OD600 values of just 0.5 ± 0.1 (Figure 2C). No bifidobacterial strain was able to grow in bCDMPRL2010.

Sulfur Amino Acid Metabolism of B. bifidum PRL2010

A general prediction based on genomic data about nitrogen metabolism within the genus Bifidobacterium was previously reported by (Milani et al., 2014). The presence of genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis appears to be conserved among the seven phylogenetic groups of the genus Bifidobacterium (Lugli et al., 2014). However, the genes that are predicted to be involved in sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism were shown to be variably present within bifidobacterial genomes. In this context, an in silico analysis of the B. bifidum PRL2010 genome (Turroni et al., 2010) for putative genes involved in sulfur-containing amino acid transport did not reveal any positive match.

Aliphatic sulfonates can be used as alternative sulfur sources for the synthesis of cysteine (van der Ploeg et al., 1998). Bioinformatics analyses revealed the occurrence of two genes (BBPR_0202 and BBPR_0362) encoding two putative ABC-type permeases, in the chromosome of PRL2010. A low level of homology with genes involved in sulfonate transport (Even et al., 2006) was detected (Supplementary Table S1), possibly explaining why B. bifidum PRL2010 cells are unable to grow with sulfate as the only sulfur source (bCDM condition, see Figure 2A). Another mechanism to achieve sulfur from the environment is based on the intake of cysteine by symporter proteins. This type of symporter may participate in the uptake of cysteine (Vitreschak et al., 2008). In this context, a putative sodium dicarboxylate symporter gene (BBPR_0324) was identified in PRL2010 (see Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, two putative genes (BBPR_0668 and BBPR_0671) predicted to encode two carriers involved in glutamate transport system (GluA and GluD), exhibited 53 and 26% homology, respectively, with the genes that encode the L-cysteine uptake system of B. subtilis (Supplementary Table S1).

As mentioned above, B. bifidum PRL2010 cells were shown to be unable to grow in presence of reduced glutathione (and in the absence of cysteine). Such physiological findings are in agreement with in silico analyses of PRL2010 chromosome sequences. In fact, the pepT and pepM genes, which are constituting the pathway for degradation of this compound (Andre et al., 2010) to generate cysteine, are absent in PRL2010 genome. Furthermore, a homolog of the gshAB gene, which specifies the glutamate–cysteine ligase/glutathione synthase, is also absent in chromosome of PRL2010 (Figure 1).

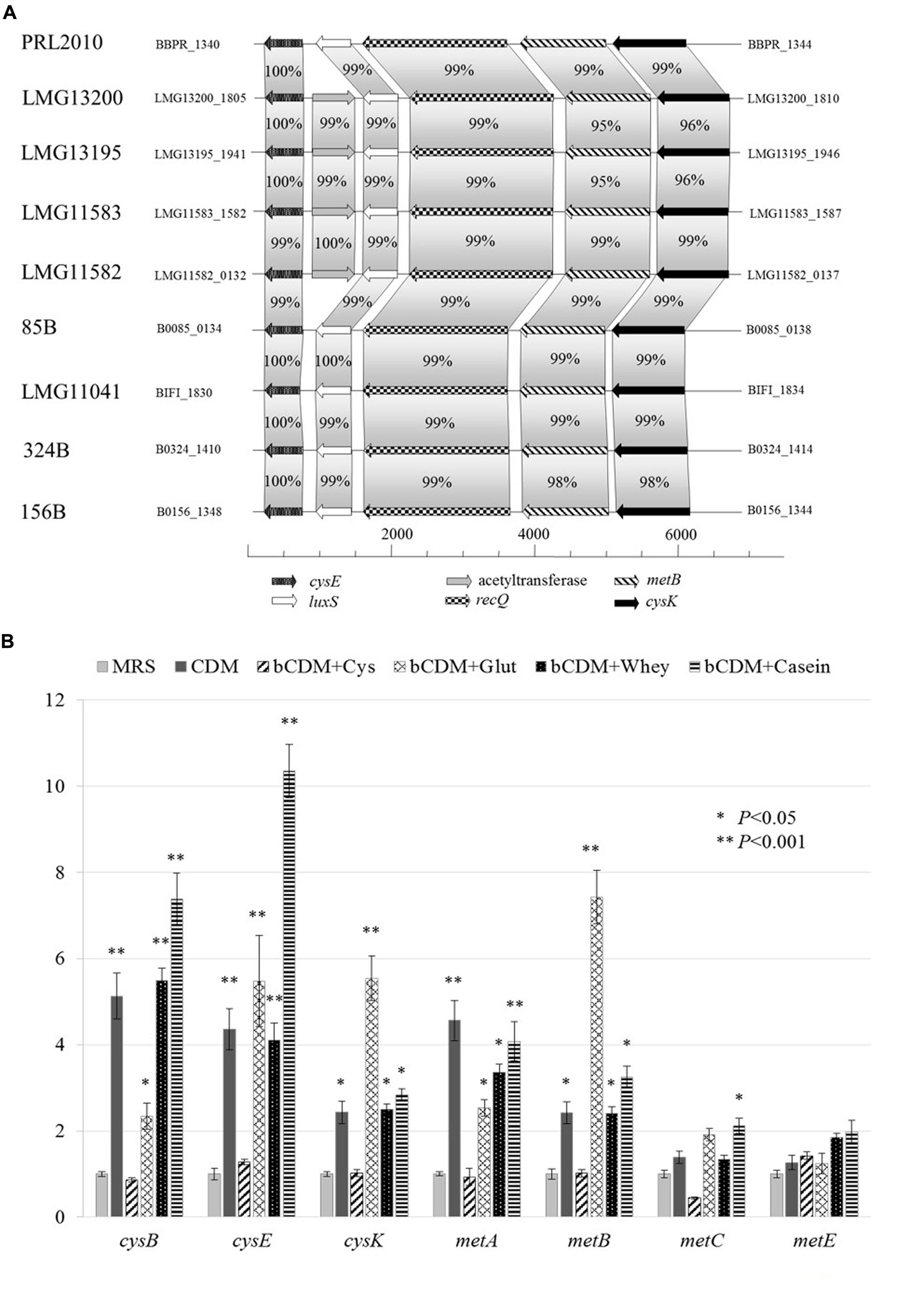

Genes predicted to be involved in the cysteine biosynthesis I/homocysteine degradation pathway and methionine biosynthesis I pathway were identified in PRL2010 (Figure 3A). In silico analyses of PRL2010 genome revealed the occurrence of the cysE (BBPR_1340) and cysK (BBPR_ 1344) genes, which encode the predicted serine acetyltransferase that transfers an acetyl group to serine, and the cysteine synthase, respectively (Liu et al., 2012) (Figure 3A). In the same genomic region, we also identified the metB gene (BBPR_1343) predicted to encode a cystathionine-γ-synthase, which is catalyzing the conversion of cysteine to cystathionine, as well as the luxS gene (BBPR_1341), encoding an _S_-ribosylhomocysteinase involved in the production of homocysteine, and the recQ gene (BBPR_1342) encoding an ATP-dependent DNA helicase. When the presence of these genes was investigated in the genomes of other B. bifidum strains (Duranti et al., 2015) included in this study, a high level of homology (higher than 98% at nucleotide level) was found. Furthermore, in the genome sequences of four B. bifidum strains, i.e., LMG13200, LMG13195, LMG11582, and LMG11583 (Duranti et al., 2015), an additional acetyltransferase-encoding gene was identified (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3. Schematic representation of genes involved in cysteine and methionine metabolism in B. bifidum species and transcriptional analysis in B. bifidum PRL2010. (A) Shows the genetic map of the predicted cysteine/methionine metabolism gene region identified in the genome of B. bifidum PRL2010 and compared with other B. bifidum strains. Each individual gene is represented by an arrow and is colored or marked according to the predicted function as indicated in the figure. (B) Reports the relative transcription levels of cysteine and methionine metabolism genes from B. bifidum PRL2010 upon cultivation in complete CDMPRL2010, bCDMPRL2010 supplemented with cysteine (bCDM + Cys), bCDMPRL2010 supplemented with glutathione (bCDM + Glut), bCDMPRL2010 with cysteine and 2% (wt/wt) whey protein (bCDM + Whey) and bCDMPRL2010 with cysteine and 2% (wt/wt) casein hydrolysate as analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR assays. The histograms indicate the relative amounts of the cysE, cysK, cysB, metA, metE, metB, and metC genes mRNAs for the specific samples. The y axis indicates the logarithmic fold induction of the investigated gene compared to the reference condition (MRS). The x axis represents the different gene tested. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to the control. The error bar for each column represent the standard deviation calculated from three replicates.

Other genes such as the cysB gene (BBPR_0960), metC (BBPR_1226) and metA (BBPR_1654) that are predicted to be involved in cysteine and methionine metabolism (Fernandez et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2012) are scattered across the PRL2010 genome.

Growth Evaluation in Complex Substrates

The effects of complex substrates, such as whey proteins or casein hydrolysate, on PRL2010 growth were tested and are reported in Figure 2D. Whey proteins and casein hydrolysate were dissolved in CDMPRL2010 and bCDMPRL2010 with or without other nitrogen sources at 0.5 or 2% concentration (wt/wt), respectively. Casein hydrolysate better supports PRL2010 growth in presence of nitrogen, compared to what was observed when this strain was cultivated on whey proteins. In CDM or bCDM without other nitrogen sources, PRL2010 cells seemed to metabolize whey proteins more efficiently as displayed by the higher OD 600 values that were reached (Figure 2D).

Targeted Gene Expression Analyses of PRL2010 with Different Sulfur Substrate

Transcription of genes involved in sulfur metabolism, such as those of cysteine (cysE, cysK and cysB) and methionine metabolism (_met_A, metE, metB, and metC), were investigated using a qRT-PCR approach, the results of which are reported in Figure 3B.

When PRL2010 cells were cultivated in the complete CDMPRL2010, cysB, cysE, cysK, metA and metB were overexpressed (P < 0.05) (Figure 3B). The occurrence of cysteine in the basal CDMPRL2010 (bCDM + Cys) does not seem to modulate expression of genes involved in sulfur amino acid metabolism. Glutathione (bCDM + Glut) does not allow a significant growth of PRL2010 (OD600 values of 0.31 ± 0.038). However, it enhanced the transcription of the cysB, cysE, cysK, metA and metB genes (P < 0.05).

Regarding complex substrates, cys genes appear to be less induced when PRL2010 cells are cultivated in whey protein compared to basal CDMPRL2010 in the presence of casein hydrolysate (bCDM + Whey and bCDM + Casein respectively in Figure 3B), although at significant level (P < 0.05). Moreover, casein hydrolysate significantly increases the transcription level of metC, the cystathionine β-liase (P < 0.05).

In all conditions tested, no significant transcriptional changes were detected for the metC and metE genes predicted to encode for cystathionine β-liase and homocysteine methyltransferase, respectively, except for metC when PRL2010 was grown in bCDMPRL2010 with casein hydrolysate.

Discussion

Following birth, the human intestine is rapidly colonized by a vast array of microorganisms. Bifidobacterium, and in particular, B. bifidum strains are abundant in breast-fed infants, due to their capacity to grow on mucin and on human milk oligosaccharides (Turroni et al., 2010). The bifidogenic effect of breast milk due to bioactive peptides presence is well known (Liepke et al., 2002). A similar bifidogenic effect was shown for milk-derived k-caseins with loss of activity when the disulfide bonds were oxidized (Poch and Bezkorovainy, 1991).

Here, we investigated for the first time sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism in B. bifidum PRL2010 through the development of a CDM called CDMPRL2010 and by the molecular characterization of the putative auxotrophic behavior of this strain for cysteine. Data indicates that bCDMPRL2010 does not support B. bifidum PRL2010 growth, unless cysteine addition. The same behavior was extended to three other B. bifidum strains, i.e., LMG13200, LMG11582 and LMG11583. Furthermore, cysteine auxotrophy is not a common feature of all the (sub)species harboring the genus Bifidobacterium, since representatives of some species such as B. boum, B. minimum, B. pullorum, B. ruminantium, B. saguini and B. scardovii are able to grow without cysteine, although rather poorly.

In silico analyses of PRL2010 genome did not reveal the presence of the genetic arsenal needed to sulfate transport and reduction to sulfide. Growth experiments showed that cysteine is the only amino acid necessary to sustain PRL2010 growth but when the strain is cultivated in basal CDMPRL2010 with cysteine (bCDM + Cys) the transcription of genes involved in cysteine and methionine metabolism was not stimulated by the availability of these amino acid residues. Similar results were reported previously for other bacterial species, such as Escherichia coli (Kredich, 1992), Bacillus subtilis (Mansilla and de Mendoza, 2000), and Lactococcus lactis (Fernandez et al., 2002). Another reduced sulfur compound was used to understand if the role of cysteine in PRL2010 is linked to the reducing effect that it exploits on the redox potential (Even et al., 2006). However, reduced glutathione does not sustain any appreciable strain growth, yet enhanced the transcription of genes predicted to be involved in sulfur amino acid metabolism (cysB, cysE, cysK, metA and metB). Similar behavior was previously reported for E. coli (Kredich, 1992) and B. subtilis (Mansilla and de Mendoza, 2000).

Complex substrates from dairy industry such as whey proteins and casein hydrolysate act as a reservoir of amino acid, peptides and free protein. Transcriptional analysis showed that whey proteins and casein hydrolysate increased the transcriptions of genes involved in serine degradation and/or conversion to cysteine and methionine (cysB, cysE, cysK metA and metB).

Conclusion

This study provides new insights into the amino acid utilization ability of the B. bifidum species. This work also suggested the existence of a relationship between the sulfur amino acid metabolism and the redox state of the cell. The use of complex nitrogen sources available in the infant gut revealed an enhancement of growth yield and expression of genes involved in sulfur amino acid metabolism in PRL2010. These results could open a new avenue of research for the development of novel functional foods based on milk caseins and whey proteins with high content of cysteine or cysteine precursor’s compounds that could act as prebiotics for Bifidobacterium enrichment.

Author Contributions

CF performed the work and wrote the manuscript, SD performed the work, CM, performed bioinformatics analyses, LM performed bioinformatics analyses, GL performed bioinformatics analyses, MM performed the work, AV performed the work, MO contributed data, DvS wrote the manuscript, MV wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Guest Associate Editor David Berry declares that despite having hosted a Frontiers Research Topic with the authors Marco Ventura and Francesca Turroni, the review process was handled objectively. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Science Foundation Ireland for financial support to DvS. This study was funded by the Irish Government’s National Development Plan (Grant number SFI/12/RC/2273) to DvS.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01331

References

Alvarez, R., Neumann, G., Fravega, J., Diaz, F., Tejias, C., Collao, B., et al. (2015). CysB-dependent upregulation of the Salmonella Typhimurium cysJIH operon in response to antimicrobial compounds that induce oxidative stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 458, 46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.058

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andre, G., Haudecoeur, E., Monot, M., Ohtani, K., Shimizu, T., Dupuy, B., et al. (2010). Global regulation of gene expression in response to cysteine availability in Clostridium perfringens. BMC Microbiol. 10:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-234

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bogicevic, B., Berthoud, H., Portmann, R., Meile, L., and Irmler, S. (2012). CysK from Lactobacillus casei encodes a protein with O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase and cysteine desulfurization activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 94, 1209–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3677-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Burguiere, P., Auger, S., Hullo, M. F., Danchin, A., and Martin-Verstraete, I. (2004). Three different systems participate in L-cystine uptake in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4875–4884. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.4875-4884.2004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carbonero, F., Benefiel, A. C., Alizadeh-Ghamsari, A. H., and Gaskins, H. R. (2012). Microbial pathways in colonic sulfur metabolism and links with health and disease. Front. Physiol. 3:448. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00448

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cronin, M., Zomer, A., Fitzgerald, G. F., and van Sinderen, D. (2012). Identification of iron-regulated genes of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 as a basis for controlled gene expression. Bioeng. Bugs 3, 157–167. doi: 10.4161/bbug.18985

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Davila, A. M., Blachier, F., Gotteland, M., Andriamihaja, M., Benetti, P. H., Sanz, Y., et al. (2013). Intestinal luminal nitrogen metabolism: role of the gut microbiota and consequences for the host. Pharmacol. Res. 68, 95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Duranti, S., Milani, C., Lugli, G. A., Turroni, F., Mancabelli, L., Sanchez, B., et al. (2015). Insights from genomes of representatives of the human gut commensal Bifidobacterium bifidum. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 2515–2531. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12743

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Even, S., Burguiere, P., Auger, S., Soutourina, O., Danchin, A., and Martin-Verstraete, I. (2006). Global control of cysteine metabolism by CymR in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 2184–2197. doi: 10.1128/Jb.188.6.2184-2197.2006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fanning, S., Hall, L. J., Cronin, M., Zomer, A., MacSharry, J., Goulding, D., et al. (2012). Bifidobacterial surface-exopolysaccharide facilitates commensal-host interaction through immune modulation and pathogen protection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2108–2113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115621109

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fernandez, M., Kleerebezem, M., Kuipers, O. P., Siezen, R. J., and van Kranenburg, R. (2002). Regulation of the metC-cysK operon, involved in sulfur metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 184, 82–90. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.1.82-90.2002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hamer, H. M., De Preter, V., Windey, K., and Verbeke, K. (2012). Functional analysis of colonic bacterial metabolism: relevant to health? Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 302, G1–G9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kredich, N. M. (1992). The molecular-basis for positive regulation of Cys promoters in _Salmonella_-Typhimurium and Escherichia-Coli. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 2747–2753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01453.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lebeer, S., De Keersmaecker, S. C. J., Verhoeven, T. L. A., Fadda, A. A., Marchal, K., and Vanderleyden, J. (2007). Functional analysis of luxS in the probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reveals a central metabolic role important for growth and Biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 189, 860–871. doi: 10.1128/Jb.01394-06

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liepke, C., Adermann, K., Raida, M., Magert, H. J., Forssmann, W. G., and Zucht, H. D. (2002). Human milk provides peptides highly stimulating the growth of bifidobacteria. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 712–718. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02712.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, M. J., Prakash, C., Nauta, A., Siezen, R. J., and Francke, C. (2012). Computational analysis of cysteine and methionine metabolism and its regulation in dairy starter and related bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 194, 3522–3533. doi: 10.1128/JB.06816-11

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lugli, G. A., Milani, C., Turroni, F., Duranti, S., Ferrario, C., Viappiani, A., et al. (2014). Investigation of the evolutionary development of the genus Bifidobacterium by comparative genomics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6383–6394. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02004-14

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mansilla, M. C., and de Mendoza, D. (2000). The Bacillus subtilis cysP gene encodes a novel sulphate permease related to the inorganic phosphate transporter (Pit) family. Microbiology 146(Pt 4), 815–821. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-4-815

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Marcobal, A., Southwick, A. M., Earle, K. A., and Sonnenburg, J. L. (2013). A refined palate: bacterial consumption of host glycans in the gut. Glycobiology 23, 1038–1046. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt040

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McCann, K. B., Shiell, B. J., Michalski, W. P., Lee, A., Wan, J., Roginski, H., et al. (2006). Isolation and characterisation of a novel antibacterial peptide from bovine alpha(s1)-casein. Int. Dairy J. 16, 316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyl.2005.05.005

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Milani, C., Lugli, G. A., Duranti, S., Turroni, F., Bottacini, F., Mangifesta, M., et al. (2014). Genomic encyclopedia of type strains of the genus Bifidobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6290–6302. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02308-14

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nagpal, R., Behare, P., Rana, R., Kumar, A., Kumar, M., Arora, S., et al. (2011). Bioactive peptides derived from milk proteins and their health beneficial potentials: an update. Food Funct. 2, 18–27. doi: 10.1039/c0fo00016g

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

O’Connell Motherway, M., Zomer, A., Leahy, S. C., Reunanen, J., Bottacini, F., Claesson, M. J., et al. (2011). Functional genome analysis of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 reveals type IVb tight adherence (Tad) pili as an essential and conserved host-colonization factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11217–11222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105380108

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Petry, S., Furlan, S., Crepeau, M. J., Cerning, J., and Desmazeaud, M. (2000). Factors affecting exocellular polysaccharide production by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp bulgaricus grown in a chemically defined medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 3427–3431. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.8.3427-3431.2000

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Poch, M., and Bezkorovainy, A. (1991). Bovine-milk kappa-casein trypsin digest is a growth enhancer for the genus Bifidobacterium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 39, 73–77. doi: 10.1021/jf00001a013

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schanbacher, F. L., Talhouk, R. S., and Murray, F. A. (1997). Biology and origin of bioactive peptides in milk. Livestock Prod. Sci. 50, 105–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.06.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Singh, P., Brooks, J. F. II, Ray, V. A., Mandel, M. J., and Visick, K. L. (2015). CysK plays a role in biofilm formation and colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 5223–5234. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00157-15

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turroni, F., Bottacini, F., Foroni, E., Mulder, I., Kim, J. H., Zomer, A., et al. (2010). Genome analysis of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 reveals metabolic pathways for host-derived glycan foraging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19514–19519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011100107

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turroni, F., Foroni, E., Montanini, B., Viappiani, A., Strati, F., Duranti, S., et al. (2011). Global genome transcription profiling of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 under in vitro conditions and identification of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8578–8587. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06352-11

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turroni, F., Peano, C., Pass, D. A., Foroni, E., Severgnini, M., Claesson, M. J., et al. (2012a). Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 7:e36957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turroni, F., Strati, F., Foroni, E., Serafini, F., Duranti, S., van Sinderen, D., et al. (2012b). Analysis of predicted carbohydrate transport systems encoded by Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5002–5012. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00629-12

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turroni, F., Serafini, F., Foroni, E., Duranti, S., O’Connell Motherway, M., Taverniti, V., et al. (2013). Role of sortase-dependent pili of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 in modulating bacterium-host interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11151–11156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303897110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turroni, F., Taverniti, V., Ruas-Madiedo, P., Duranti, S., Guglielmetti, S., Lugli, G. A., et al. (2014). Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 modulates the host innate immune response. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 730–740. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03313-13

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Underwood, M. A., German, J. B., Lebrilla, C. B., and Mills, D. A. (2015). Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis: champion colonizer of the infant gut. Pediatr. Res. 77, 229–235. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.156

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

van der Ploeg, J. R., Cummings, N. J., Leisinger, T., and Connerton, I. F. (1998). Bacillus subtilis genes for the utilization of sulfur from aliphatic sulfonates. Microbiology 144(Pt 9), 2555–2561. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2555

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ventura, M., Turroni, F., Motherway, M. O., MacSharry, J., and van Sinderen, D. (2012). Host-microbe interactions that facilitate gut colonization by commensal bifidobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 20, 467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.07.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Vitreschak, A. G., Mironov, A. A., Lyubetsky, V. A., and Gelfand, M. S. (2008). Comparative genomic analysis of T-box regulatory systems in bacteria. RNA 14, 717–735. doi: 10.1261/rna.819308

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ye, J., Coulouris, G., Zaretskaya, I., Cutcutache, I., Rozen, S., and Madden, T. L. (2012). Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 13:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134