Frontiers | Exosomes/miRNAs as mediating cell-based therapy of stroke (original) (raw)

REVIEW article

Front. Cell. Neurosci., 10 November 2014

Sec. Cellular Neuropathology

This article is part of the Research Topic Stem cells and progenitor cells in ischemic stroke – fashion or future? View all 16 articles

- 1Department of Neurology, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA

- 2Department of Physics, Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Cell-based therapy, e.g., multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) treatment, shows promise for the treatment of various diseases. The strong paracrine capacity of these cells and not their differentiation capacity, is the principal mechanism of therapeutic action. MSCs robustly release exosomes, membrane vesicles (~30–100 nm) originally derived in endosomes as intraluminal vesicles, which contain various molecular constituents including proteins and RNAs from maternal cells. Contained among these constituents, are small non-coding RNA molecules, microRNAs (miRNAs), which play a key role in mediating biological function due to their prominent role in gene regulation. The release as well as the content of the MSC generated exosomes are modified by environmental conditions. Via exosomes, MSCs transfer their therapeutic factors, especially miRNAs, to recipient cells, and therein alter gene expression and thereby promote therapeutic response. The present review focuses on the paracrine mechanism of MSC exosomes, and the regulation and transfer of exosome content, especially the packaging and transfer of miRNAs which enhance tissue repair and functional recovery. Perspectives on the developing role of MSC mediated transfer of exosomes as a therapeutic approach will also be discussed.

Introduction

The therapeutic effects of cell-based therapy, such as for the treatment of stroke, with multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have demonstrated particular promise. Systemic administration of MSCs as a treatment for stroke (Chen et al., 2001a,b; Li et al., 2001; Chopp and Li, 2002; Hessvik et al., 2013), has demonstrated that MSCs promote central nervous system (CNS) plasticity and neurovascular remodeling which lead to functional benefit (Caplan and Dennis, 2006; Zhang et al., 2006b; Chopp et al., 2008; Dharmasaroja, 2009; Li and Chopp, 2009; Zhang and Chopp, 2009, 2013; Borlongan et al., 2011; Herberts et al., 2011). Instead of the replacement of damaged cells, cell-based therapy provides therapeutic benefit by remodeling of the CNS, i.e., by promoting neuroplasticity, angiogenesis and immunomodulation (Chen et al., 2001b; Chopp and Li, 2002; Chopp et al., 2008; Li and Chopp, 2009; Zhang and Chopp, 2013; Liang et al., 2014). Early studies posited that the therapeutic efficacy of transplanted MSCs was attributed to their subsequent differentiation into parenchymal cells which repairs and replaces damaged tissues. However, studies in animal models and patients demonstrated that only a very small number of transplanted MSCs localize to the damage site and surrounding area, while most of the MSCs were localized in the liver, spleen and lungs (Phinney and Prockop, 2007). In addition, apparent evidence of MSC differentiation likely resulted from the fusion of transplanted MSCs with endogenous cells (Spees et al., 2003; Vassilopoulos et al., 2003; Konig et al., 2005; Ferrand et al., 2011). Supported by robust data, our present understanding of how MSCs promote neurological recovery is through their interaction with brain parenchymal cells. MSCs produce and induce within parenchymal cells biological effectors, e.g., neurotrophic factors, proteases, and morphogens, which subsequently enhance the neurovascular microenvironment surrounding the damaged area, as well as remodel remote tissue (Chen et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2002; Mahmood et al., 2004; Gao et al., 2005, 2008; Xin et al., 2006, 2010, 2011, 2013a; Zhang et al., 2006c, 2009; Qu et al., 2007; Zacharek et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2008, 2010, 2011b; Xu et al., 2010; Hermann and Chopp, 2012; Ding et al., 2013; Zhang and Chopp, 2013). Though the mechanisms which underlie the interaction and communication between the exogenously administered cells, e.g., MSCs, and brain parenchymal cells are not fully understood, the paracrine effect hypothesis has been strengthened by recent evidence that stem cells release extracellular vesicles which elicit similar biological activity to the stem cells themselves (Lai et al., 2011; Camussi et al., 2013; Xin et al., 2013b). These released extracellular lipid vesicles, provide a novel means of intercellular communication (Raposo and Stoorvogel, 2013; Fujita et al., 2014; Record et al., 2014; Turturici et al., 2014; Zhang and Grizzle, 2014). A particularly important class of extracellular vesicles released by stem cells and MSCs, is exosomes, and accumulating data show that MSCs release large amounts of exosomes which mediate the communication of MSCs with other cells (Collino et al., 2010; Hass and Otte, 2012; He et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Roccaro et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). Here, we focus our discussion on exosomes derived from MSCs, the biogenesis of MSC exosomes, cargo packaging (especially the miRNAs) and intercellular communication, and discuss new opportunities in modifying exosomal cargo to develop exosome-based cell-free therapeutics.

Characteristic of Exosomes

Lipid vesicles can be released by various types of cells, and they have been found in the supernatants from a wide variety of cells in culture, as well as in all bodily fluids (Yang et al., 2014; Yellon and Davidson, 2014; Zhang and Grizzle, 2014). The shedding of microvesicles and exosomes is likely a general property of most cells. Initial studies on cell released vesicles were reported in the 1960s (Roth and Luse, 1964; Schrier et al., 1971; Dalton, 1975), and the most common term, exosome, as applied to cell-derived vesicles was first defined by Trams et al. (1981); since they believe that these “exfoliated membrane vesicles may serve a physiologic function” and “it is proposed that they be referred to as exosomes” (Trams et al., 1981), (Box 1, nomenclature).

Box 1. Nomenclature.

Currently, the use of the term ‘exosomes’ for MVB-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) is widely accepted in the field; however, the large variety of EVs secreted by cells and the technical difficult to definitively discriminate small EVs from exosomes in the culture media using currently available methods has led to the less stringent usage of the term, exosomes. Exosomes are presently characterized as either small EVs (of 30–100 nm diameter) measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM)), or as EVs recovered after 100000g ultracentrifugation. As Gould and Raposo proposed recently, given the absence of perfect identification of EVs′ of endosomal origin, researchers are recommended to explicitly state their use of terms, choose their terms based on precedent and logical argument, and apply them consistently throughout a piece of work (Gould and Raposo, 2013). Since the EVs identified and employed in our studies fulfill the above mentioned two characteristics (i.e.,TEM and 100000g untracentrifugation), therefore, exosomes are likely the primary constituents of the EVs. Here, in this manuscript, we use the term ‘exosomes’ as defined by Trams et al. (Trams et al., 1981), however, we do not exclude the possibility of other non-exosomal microvesicle components within the content of our injected precipitate, and we do not exclude a contribution of non-exosomal microvesicles to mediating stroke recovery.

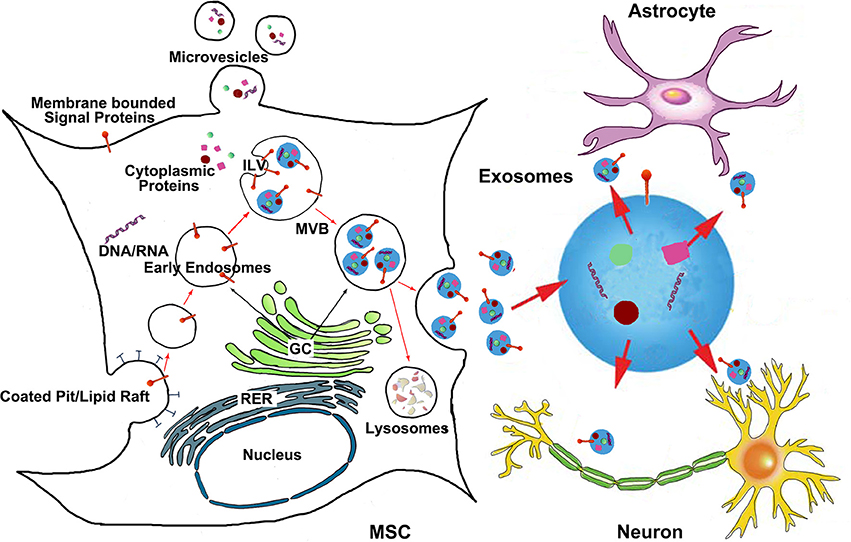

Extracellular released vesicles mainly include exosomes and microvesicles (Momen-Heravi et al., 2013). Exosomes are endocytic origin small-membrane vesicles. Eukaryotic cells periodically engulf small amounts of intracellular fluid in the specific membrane area, forming a small intracellular body called endosome (Thery et al., 2002). The early endosome matures and develops into the late endosome, during the maturation process, the inward budding of the endosomal membrane forms the intraluminal vesicles (ILV) which range in size from approximately 30–100 nm in diameter. The late endosome containing ILVs is also referred to as, a multivesicular body (MVB) and proteins are directly sorted to the MVBs from rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex (Thery et al., 1999), as are mRNAs, microRNAs, and DNAs (Villarroya-Beltri et al., 2013). The MVBs may either fuse with the lysosome and degrade their contents or fuse with the plasma membrane of the cell, releasing their ILVs to the extracellular environment (Figure 1). These vesicles are then referred as exosomes (Van Niel et al., 2006). Microvesicles are small, plasma membrane derived particles that are released into the extracellular environment by the outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane (Amano et al., 2001; Cocucci et al., 2009; Muralidharan-Chari et al., 2010). Unlike the large size of microvesicle (100~1000 nm in diameter), exosomes have a smaller size, ~30–100 nm in diameter (Stoorvogel et al., 2002). Exosome density in sucrose is located at 1.13–1.19 g/ml, and exosomes can be collected by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g (Thery et al., 2006). The exosome membranes are enriched with cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and ceramide which are contained in lipid rafts (Thery et al., 2006). Most exosomes contain conserved proteins such as tetraspanins (CD81, CD63, and CD9), Alix and Tsg101, as well as the unique tissue/cell type specific proteins that reflect their cellular source. A precise and clear distinction between these vesicles (exosomes and microvesicles) is still lacking, and it is technically difficult to definitively separate them from the culture media by currently available methods like ultracentrifugation, density gradient separation, chromatography and immunoaffinity capture methods (Corrado et al., 2013). Exosomes are released by most cell types under physiological conditions. The amount of exosomes released from MSCs is highly related to cellular proliferation rate, and the exosome production is inversely correlated to the developmental maturity of the MSCs (Chen et al., 2013b). The release of extracellular vesicles can be altered by cellular stress and damage (Hugel et al., 2005; Greenwalt, 2006). Increased release of extracellular vesicles is associated with the acute and active phases of several neurological disorders (Hugel et al., 2005; Horstman et al., 2007). The distinctions between exosomes and other extracellular vesicles (such as microvesicles) are beyond the scope of this review and will not be discussed in detail here.

Figure 1. The generation of MSC exosomes and bio-information shuttling between MSCs and brain parenchymal cells via exosomes. Exosomes are generated in the late endosomal compartment by inward budding of the limiting membrane of MVB. The exosome-filled MVBs are either fused with the plasma membrane to release exosomes or sent to lysosomes for degradation. Microvesicles are plasma membrane derived particles that are released into the extracellular environment by the direct outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane. The bio-information carried by MSC exosomes then transfer to brain parenchymal cells like astrocytes and neurons. ILV, intraluminal vesicles; MVB, multivesicular body; GC, Golgi complex; RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum.

MSCs Robustly Release Exosomes

Human MSC conditioned medium can reduce myocardial infarct size in patients with acute myocardial infarction (Timmers et al., 2007), and Reduction of myocardial infarct size by human mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium, probably by increasing myocardial perfusion (Timmers et al., 2011). These therapeutic effects were then subsequently attributed to MSC derived exosomes (Lai et al., 2010). Thereafter, MSC exosomes were widely observed and tested in several disease models (Lee et al., 2012; Reis et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013; Tomasoni et al., 2013; Sdrimas and Kourembanas, 2014; Tan et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014).

Compared to other cells, MSCs can produce large amounts of exosomes (Yeo et al., 2013). There are no differences in terms of morphological features, isolation and storage conditions between exosomes derived from MSCs and other sources (Yeo et al., 2013). The MSC is the most prolific exosome producer when compared to other cell types known to produce exosomes (Yeo et al., 2013). By transfecting human ESC-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hESC-MSCs) with a lentivirus carrying myc gene, Chen et al. generated an immortalized hESC-MSCs cell line. Exosomes from MYC-transformed MSCs were able to reduce relative infarct size in a mouse model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. They found that MYC transformation may be a practical strategy in ensuring an infinite supply of cells for the production of exosomes in the milligram range as either therapeutic agents or delivery vehicles. Additionally, the increased proliferative rate by MYC transformation reduces the time for cell production and thereby reduces production costs. Chen et al. (2011), thus, making MSCs an efficient and effective “factory” for mass production of exosomes.

The Cargo of MSC Exosomes

Exosomes are complex “living” structures generated by many cell types containing a multitude of cell surface receptors (Shen et al., 2011a; Yang and Gould, 2013), encapsulating proteins, trophic factors, miRNAs, and RNAs (Koh et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2011, 2012, 2013b; Record et al., 2011; Xin et al., 2012; Chen and Lim, 2013; Katakowski et al., 2013; Tomasoni et al., 2013; Yeo et al., 2013). These bioactive molecules can mediate exosomal intercellular communication (Zhang and Grizzle, 2014; Zhang and Wrana, 2014).

The exosome cargo is dependent on the cell type of origin (Raposo and Stoorvogel, 2013). Besides the common surface markers of exosomes, such as CD9 and CD81, MSCs contain specific membrane adhesive molecules, including CD29, CD44, and CD73 that are expressed on the MSC generated exosomes (Lai et al., 2012). Further, the specific conditions of cell preparation affect the exosome cargo (Kim et al., 2005; Park et al., 2010). In the MSC derived exosome, protein components also changed when exosomes were obtained from different MSC cultured media. In their study, Lai et al. found that 379, 432, and 420 unique proteins, detected by means of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry in three independent batches of MSC derived exosomes, and only 154 common proteins are present (Lai et al., 2012). In addition to the protein cargo, RNAs, e.g., messenger RNA (mRNA) and miRNAs are encapsulated in MSC exosomes. MiRNAs encapsulated in MSC-derived microparticles are predominantly in their precursor form (Chen et al., 2010). However, other studies have demonstrated that various miRNAs are present in MSC exosomes, and the miRNA cargo participates in the cell-cell communication to alter the fate of recipient cells (Koh et al., 2010; Xin et al., 2012, 2013c; Katakowski et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2013; Ono et al., 2014).

Environmental challenges, such as activation or stress conditions, influence the composition, biogenesis, and secretion of exosomes. Possibly, exosome secretion is an efficient adaptive mechanism that cells modulate intracellular stress situations and modify the surrounding environment via the secretion of exosomes. By preconditioning (Yu et al., 2013) or genetic manipulation (Kim et al., 2007b) of dendritic cells, the exosome secretion profile of these cells can be modified. The proteomic profiles of adipocyte-derived exosomes have been characterized (Sano et al., 2014). The authors found that protein content of the exosomes produced from cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes was changed when they exposed the cells to hypoxic conditions. Quantitative proteomic analysis showed that 231 proteins were identified in the adipocyte-derived exosomes, and the expression levels of some proteins were altered under hypoxic conditions. The total amount of proteins in exosomes increased by 3-4-fold under hypoxic conditions (Sano et al., 2014). Another study found that the miRNA content of dendritic cell exosomes was affected by the maturation of the cells (Montecalvo et al., 2012), and similarly, compared with those from control cells, exosomes from mast cells contain different mRNAs when the cells were exposed to oxidative stress (Eldh et al., 2010). Furthermore, stressed cells that released exosomes conferred resistance against oxidative stress to recipient cells (Eldh et al., 2010), suggesting that cells modulate intracellular stress situations and modify the surrounding environment via the secretion of exosomes. The MSC exosome profile can be modified by pretreatment, as well. When MSCs were in vitro exposed to brain tissue extracted from rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo), the miR-133b levels in MSCs and their released exosomes were significantly increased compared to MSCs exposed to normal rat brain tissue extracts (Xin et al., 2012), indicating that MSCs used for stroke treatment will modify their gene expression and subsequently affect their exosome cargo. Thus, there is a feedback between the MSC and its environment, and through which ischemic conditions will modify the exosome contents, and consequently, the secreted exosomes affect and modify the tissue environment. Though we only tested one specific miRNA in our study, it is reasonable to propose that other miRNAs or other cargos of MSC exosome were modified by the post ischemic condition. i.e., other groups also demonstrated that miR-22 in MSC exosomes were enriched following ischemic preconditioning (Feng et al., 2014).

MSC Derived Exosomes Transfer Bio-Information to Recipient Cells via miRNA

MiRNAs are non-protein coding, short ribonucleic acid (usually 18–25 nucleotides) molecules found in eukaryotic cells. Via binding to complementary sequences on target mRNA transcripts, miRNAs post-transcriptionally control gene expression (Bartel, 2004, 2009). MiRNAs constitute a major regulatory gene family in eukaryotic cells (Bartel, 2004; Zhang et al., 2006a, 2007; Fiore et al., 2008). MiRNAs are master molecular switches, concurrently affecting translation of, possibly, hundreds of mRNAs (Cai et al., 2009; Agnati et al., 2010). Over 1000 miRNAs are encoded by the human genome (Bartel, 2004) and they target about 60% of mammalian genes (Lewis et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2009), and are abundant in many human cell types (Lim et al., 2003). By affecting gene expression, miRNAs are likely involved in most biological processes (Brennecke et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Cuellar and McManus, 2005; Harfe et al., 2005; Lim et al., 2005). Based on the master gene regulation role of miRNAs, though MSC exosomes have the potential for protein cargo transfer (Zhang et al., 2014), we envisage that compared with the delivery of proteins, transfer of miRNA may have dramatic effects on the network of proteins and RNAs of the recipient cells.

Exosomes are well suited for small functional molecule delivery (Zomer et al., 2010). Increasing evidence indicates that they play a pivotal role in cell-to-cell communication (Mathivanan et al., 2010) and act as biological transporters (Denzer et al., 2000; Fevrier and Raposo, 2004; Lotvall and Valadi, 2007; Smalheiser, 2007; Valadi et al., 2007; Mathivanan et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011; Record et al., 2011; Von Bartheld and Altick, 2011; Mittelbrunn and Sanchez-Madrid, 2012; Boon and Vickers, 2013; Raposo and Stoorvogel, 2013). Importantly, by being encapsulated and contained within the exosomes, the RNA is protected from the digestion of RNAase or trypsin (Valadi et al., 2007). Multiple studies show that exosomes transfer miRNAs to recipient cells (Valadi et al., 2007; Hergenreider et al., 2012). The transferred miRNAs then modify the recipient cell's characteristics. Shimbo et al. introduced synthetic miR-143 into cells, and the miR-143 was enveloped in released exosomes (Shimbo et al., 2014). The secreted exosome-formed miR-143 is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and subsequently significantly reduced the migration of osteosarcoma cells (Shimbo et al., 2014). Recent studies show that MSC exosomes regulate recipient cell protein expression and modify cell characteristics through the miRNA transfer (Xin et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). Exosomal transfer of miR-23b from the bone marrow may promote breast cancer cell dormancy in a metastatic niche (Ono et al., 2014). The master gene regulation role of miRNAs encapsulated within exosomes, determines their major role in the modification of recipient cells.

Exosomes Shuttle miRNAs as Regulators for Stroke Recovery After MSC Therapy

In the nervous system, exosomes mediate cell-cell communication including the transfer of synaptic proteins, mRNAs and microRNAs (Smalheiser, 2007). The role of miRNAs at various stages of neuronal development and maturation has been recently elucidated (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009; Saba and Schratt, 2010; Olde Loohuis et al., 2012). Numerous miRNAs are expressed in spatially and temporally controlled manners in the nervous system (Kapsimali et al., 2007; Bak et al., 2008; Dogini et al., 2008; Kocerha et al., 2009; Sethi and Lukiw, 2009; Ziu et al., 2011), suggesting that miRNAs have important functions in the gene regulatory networks involved in adult neural plasticity (Sethi and Lukiw, 2009; Liu and Xu, 2011; Mor et al., 2011; Goldie and Cairns, 2012). Stroke induces changes in the miRNA profile of MSCs and within their released exosomes (Jeyaseelan et al., 2008; Lusardi et al., 2014), and miRNAs actively participate in the recovery process after stroke (Liu et al., 2013).

MiR-133b promotes functional recovery in Parkinson's disease (Kim et al., 2007a) and appears essential for neurite outgrowth and functional recovery after spinal cord injury in adult zebra-fish (Yu et al., 2011). Moreover, miR-133b regulates the expression of its targets, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a major inhibitor of axonal growth at injury sites in the CNS in mammals (White and Jakeman, 2008; Duisters et al., 2009) and down-regulates Ras homolog gene family, member A (RhoA) protein expression (Care et al., 2007; Chiba et al., 2009). In our series of studies, we first found that miR-133b is substantially down-regulated in rat brain after MCAo, and MSC administration significantly increased the miR-133b level in the ischemic cerebral tissue. When MSCs were exposed to ischemic brain extracts, the miR-133b level was increased in exosomes released from these MSCs. We then treated primary cultured neurons and astrocytes with these exosomes, and found the miR-133b level in the neurons and astrocytes were increased, suggesting that the exosomes mediate the miR-133b transfer from MSCs to the neurons and astrocytes. Further in vitro knockdown of miR-133b in MSCs directly confirmed that the increased miR-133b level in astrocytes is attributed to their transfer from MSCs to neural cells, and exosomal miR-133b from MSCs significantly increased the neurite branch number and total neurite length (Xin et al., 2012). Compared with administration of normal MSCs, in vivo administration of MSCs with increased or decreased miR-133b (MSCs modified using lentivirus with miR-133b knocked-in or knocked-down) to rats subjected to MCAo resulted in promotion or inhibition of neurite outgrowth, respectively (Xin et al., 2012). Correspondingly, in vitro and in vivo, we also observed the transfer of miR-133b from MSCs to astrocytes via exosomes down-regulated CTGF expression, which may thin the glial scar and benefit neurite outgrowth. In contrast, treatment of stroke in rats with MSCs containing increased miR-133b, inhibited RhoA expression in neurons which enhanced the regrowth of the corticospinal tract after injury (Dergham et al., 2002; Holtje et al., 2009). Down-regulation of CTGF and RhoA by miR-133b stimulated neurite outgrowth and thereby improved functional recovery after stroke (Xin et al., 2012). This proof-of-concept study, provides the first demonstration that MSCs communicate with astrocytes and neurons and regulate neurite outgrowth by transfer of miRNAs (miR-133b) via exosomes. The identification of exosomes released from MSCs as a shuttle that carries miR-133b to astrocytes and neurons after cerebral ischemia helps to explain, at least in-part, how the exogenous MSCs contribute to neurological recovery after stroke. Exosome delivery of functional miRNAs, e.g., miR-133b, that promote neurite outgrowth may show benefit in other neurological diseases, in addition to stroke.

Exosomes as an Alternative Therapeutic Candidate of MSCs on Stroke

MSC exosomes serve as a vehicle to transfer protein, mRNA, and miRNA to distant recipient cells, altering the gene expression of the recipient cells. Recently, MSC exosomes have been found to be efficacious in an increasing number of animal models for the treatment of diseases such as liver fibrosis (Li et al., 2013), liver injury (Tan et al., 2014), hypoxic pulmonary hypertension (Lee et al., 2012), acute lung injury (Sdrimas and Kourembanas, 2014; Zhu et al., 2014), acute kidney injury (Gatti et al., 2011; Reis et al., 2012; Tomasoni et al., 2013), and cardiovascular diseases (Lai et al., 2011). We demonstrated that systemic treatment of stroke with cell-free exosomes derived from MSCs significantly improve neurological outcome and contribute to neurovascular remodeling (Xin et al., 2013b). This approach is the first to consider treatment of stroke solely with exosomes.

Development of gene therapy vehicles for diffuse delivery to the brain is one of the major challenges for clinical gene therapy. By using miRNA mimics or antagonists, miRNA-based strategies have recently emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for specific diseases. However, despite its exciting potential, the bottleneck of this approach is delivery of miRNA; an optimal delivery system must be found before their clinical application. Researchers developed a number of miRNA delivery systems (Zhang et al., 2013), including liposomes (Lv et al., 2006), and peptide transduction domain–double-stranded RNA-binding domain (Eguchi and Dowdy, 2009). However, synthetic materials which are employed in the above systems, limited their use. Thus, the advantages of exosomes as delivery systems are apparent; they only contain biogenic substances and are readily transferred into target cells, as well as they have potentially wide utility for the delivery of nucleic acids, and possibly for selectively targeting cells. We and others have shown that MSCs can act as “factories” for the generation of exosomes, and that the cargo within these exosomes, including the miRNAs, may be regulated by altering the genetic character of the MSCs, e.g., by transfecting the MSCs with specific genes (Zomer et al., 2010; Bullerdiek and Flor, 2012; Hu et al., 2012; Katakowski et al., 2013; Xin et al., 2013c). We have also successfully modulated the miRNA content of the MSC generated exosomes and thereby modulated neurovascular plasticity and neurological recovery from stroke (Xin et al., 2013c). Given that MSC exosomes promote recovery (Xin et al., 2013b) and MSCs release exosomes in vivo, we propose that MSC generated exosomes with enhanced expression of beneficial miRNAs (e.g., miR-133b) may provide improved recovery benefits.

Another development direction for the exosome treatment of disease is the targeting of recipient cells. We demonstrate a significant therapeutic and neuroplasticity effect of systemic exosome administration (Xin et al., 2013b). Considering the nano size of exosomes, they likely enter into the brain (Lakhal and Wood, 2011). Adhesive molecules are expressed on the exosome membrane (Clayton et al., 2004), which may facilitate entry into the brain. Thus, systemic exosome administration may be a means by which to deliver the active components of cell-based therapy to the CNS. To improve exosomal targeting, we may also consider engineering and tailoring cell membrane proteins, e.g., the engineering of dendritic cells to express an exosomal membrane protein, Lamp2b, fused to the neuron-specific RVG peptide3 (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011). Alvarez-Erviti et al. demonstrated effective delivery of functional siRNA into mouse brain by systemic injection of exosomes, and targeted the exosomes to neurons (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011). These data indicate that specifically targeting neural cells is feasible by modifying exosomal membrane proteins.

Conclusion and Prospects

Exosomes derived from MSCs, carry, and transfer their cargo (e.g., miRNAs) to parenchymal cells, and thereby mediate brain plasticity, and the functional recovery from stroke. For the intricate blend of paracrine factors needed, exosomes may be ideal carriers for treatment of a complicated disease such as stroke. Specifically modifying the miRNA content of MSC generated exosomes to modulate the therapeutic response for stroke may enhance their therapeutic application.

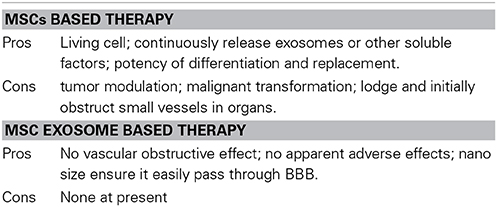

Cell-based therapies are in clinical trials for stroke and other neurological diseases (Zhou et al., 2013) and there is a robust literature on the efficacy of cell-based therapies for stroke (Hess and Borlongan, 2008). However, there are multiple benefits in transplanting exosomes rather than in transplanting the whole “factory,” the cell, into the body. In contrast to exogenously administered cells delivered systemically, exosomes, given their nano dimension may readily enter the brain and easily pass through the blood brain barrier (BBB) (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011; Kooijmans et al., 2012; Anthony and Shiels, 2013; Gheldof et al., 2013; Meckes et al., 2013). Exogenously administered MSCs may have many adverse effects, i. e. tumor modulation and malignant transformation. (Herberts et al., 2011; Wong, 2011), and they may lodge and initially obstruct small vessels in organs (Gao et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2013a). Exosomes given their min size, in contrast, have no vascular obstructive effect, and have no apparent adverse effects.

One case has been reported where exosomes were used for treatment for severe acute graft vs. host disease (Kordelas et al., 2014) in which MSC exosomes did not show any side effects. Side effects of exosome therapies were also not observed in any of the tumor vaccination studies which were performed in humans (Mignot et al., 2006; Viaud et al., 2008). Prion diseases are infectious neurodegenerative disorders linked to the accumulation of the abnormally folded prion protein (PrP) scrapie (PrPsc) in the CNS. Once present, PrPsc catalyzes the conversion of naturally occurring cellular PrP (PrPc) to PrPsc. Recent studies show both PrPc and PrPsc were actively released into the extracellular environment by PrP-expressing cells before and after infection with sheep prions, respectively, and the release associated with exosomes. Even though EV administration appears safe and no side effects have been observed so far, it should be noted, that exosomes may contribute to intercellular membrane exchange and the spread of prions (Fevrier et al., 2004; Klohn et al., 2013). Since fetal calf serum is used for in vitro culturing MSCs and amplifying the exosomes, it may bring the risk of prion disease spreading by exosomes, but this risk may be carried by in vitro cultured MSCs as well. However, the risk associated with exosome therapies is rather low. Table 1 shows the pros and cons of MSCs based therapy and MSC exosomes based therapy.

Table 1. Pros and Cons of MSCs based therapy and MSC exosomes based therapy.

Technical issues, such as, purity of exosomes must be addressed, since the most common isolation protocol with differential centrifugation and a sucrose gradient yield a heterogeneous product (EL Andaloussi et al., 2013; Lai et al., 2013a). Methods for mass exosome isolation should also be developed to reduce costs. For the modified exosome application, the exosome product needs to be extensively characterized, in order to assess its biological function and to avoid adverse effects.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AG037506 (Michael Chopp), R01 NS066041 (Yi Li) and R01 NS081189 (Hongqi Xin).

References

Agnati, L. F., Guidolin, D., Guescini, M., Genedani, S., and Fuxe, K. (2010). Understanding wiring and volume transmission. Brain Res. Rev. 64, 137–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.03.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alvarez-Erviti, L., Seow, Y., Yin, H., Betts, C., Lakhal, S., and Wood, M. J. (2011). Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 341–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1807

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Amano, T., Furuno, T., Hirashima, N., Ohyama, N., and Nakanishi, M. (2001). Dynamics of intracellular granules with CD63-GFP in rat basophilic leukemia cells. J. Biochem. 129, 739–744. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002914

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bak, M., Silahtaroglu, A., Moller, M., Christensen, M., Rath, M. F., Skryabin, B., et al. (2008). MicroRNA expression in the adult mouse central nervous system. RNA 14, 432–444. doi: 10.1261/rna.783108

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Borlongan, C. V., Glover, L. E., Tajiri, N., Kaneko, Y., and Freeman, T. B. (2011). The great migration of bone marrow-derived stem cells toward the ischemic brain: therapeutic implications for stroke and other neurological disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brennecke, J., Hipfner, D. R., Stark, A., Russell, R. B., and Cohen, S. M. (2003). bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113, 25–36. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00231-9

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Care, A., Catalucci, D., Felicetti, F., Bonci, D., Addario, A., Gallo, P., et al. (2007). MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 13, 613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, J., Li, Y., Wang, L., Lu, M., Zhang, X., and Chopp, M. (2001a). Therapeutic benefit of intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 189, 49–57. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(01)00557-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, J., Li, Y., Wang, L., Zhang, Z., Lu, D., Lu, M., et al. (2001b). Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke 32, 1005–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.4.1005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, K., Page, J. G., Schwartz, A. M., Lee, T. N., Dewall, S. L., Sikkema, D. J., et al. (2013a). False-positive immunogenicity responses are caused by CD20(+) B cell membrane fragments in an anti-ofatumumab antibody bridging assay. J. Immunol. Methods 394, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.04.011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, T. S., Arslan, F., Yin, Y., Tan, S. S., Lai, R. C., Choo, A. B., et al. (2011). Enabling a robust scalable manufacturing process for therapeutic exosomes through oncogenic immortalization of human ESC-derived MSCs. J. Transl. Med. 9, 47. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-47

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, T. S., Lai, R. C., Lee, M. M., Choo, A. B., Lee, C. N., and Lim, S. K. (2010). Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 215–224. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp857

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, T. S., Yeo, R. W. Y., Arslan, F., Yin, Y., Tan, S. S., Lai, R. C., et al. (2013b). Efficiency of exosome production correlates inversely with the developmental maturity of MSC donor. J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 3:145. doi: 10.4172/2157-7633.1000145

Chen, X., Li, Y., Wang, L., Katakowski, M., Zhang, L., Chen, J., et al. (2002). Ischemic rat brain extracts induce human marrow stromal cell growth factor production. Neuropathology 22, 275–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2002.00450.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chiba, Y., Tanabe, M., Goto, K., Sakai, H., and Misawa, M. (2009). Down-regulation of miR-133a contributes to up-regulation of Rhoa in bronchial smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180, 713–719. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0325OC

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Clayton, A., Turkes, A., Dewitt, S., Steadman, R., Mason, M. D., and Hallett, M. B. (2004). Adhesion and signaling by B cell-derived exosomes: the role of integrins. FASEB J. 18, 977–979. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1094fje

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Collino, F., Deregibus, M. C., Bruno, S., Sterpone, L., Aghemo, G., Viltono, L., et al. (2010). Microvesicles derived from adult human bone marrow and tissue specific mesenchymal stem cells shuttle selected pattern of miRNAs. PLoS ONE 5:e11803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011803

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Corrado, C., Raimondo, S., Chiesi, A., Ciccia, F., De Leo, G., and Alessandro, R. (2013). Exosomes as intercellular signaling organelles involved in health and disease: basic science and clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 5338–5366. doi: 10.3390/ijms14035338

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Denzer, K., Kleijmeer, M. J., Heijnen, H. F., Stoorvogel, W., and Geuze, H. J. (2000). Exosome: from internal vesicle of the multivesicular body to intercellular signaling device. J. Cell Sci. 113(Pt 19), 3365–3374.

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | Google Scholar

Dergham, P., Ellezam, B., Essagian, C., Avedissian, H., Lubell, W. D., and McKerracher, L. (2002). Rho signaling pathway targeted to promote spinal cord repair. J. Neurosci. 22, 6570–6577.

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | Google Scholar

Ding, X., Li, Y., Liu, Z., Zhang, J., Cui, Y., Chen, X., et al. (2013). The sonic hedgehog pathway mediates brain plasticity and subsequent functional recovery after bone marrow stromal cell treatment of stroke in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.50

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dogini, D. B., Ribeiro, P. A., Rocha, C., Pereira, T. C., and Lopes-Cendes, I. (2008). MicroRNA expression profile in murine central nervous system development. J. Mol. Neurosci. 35, 331–337. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9068-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Duisters, R. F., Tijsen, A. J., Schroen, B., Leenders, J. J., Lentink, V., Van Der Made, I., et al. (2009). miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ. Res. 104, 170–178, 176p following 178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Eldh, M., Ekstrom, K., Valadi, H., Sjostrand, M., Olsson, B., Jernas, M., et al. (2010). Exosomes communicate protective messages during oxidative stress; possible role of exosomal shuttle RNA. PLoS ONE 5:e15353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015353

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Feng, Y., Huang, W., Wani, M., Yu, X., and Ashraf, M. (2014). Ischemic preconditioning potentiates the protective effect of stem cells through secretion of exosomes by targeting Mecp2 via miR-22. PLoS ONE 9:e88685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088685

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ferrand, J., Noel, D., Lehours, P., Prochazkova-Carlotti, M., Chambonnier, L., Menard, A., et al. (2011). Human bone marrow-derived stem cells acquire epithelial characteristics through fusion with gastrointestinal epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 6:e19569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019569

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fevrier, B., Vilette, D., Archer, F., Loew, D., Faigle, W., Vidal, M., et al. (2004). Cells release prions in association with exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9683–9688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308413101

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fujita, Y., Yoshioka, Y., Ito, S., Araya, J., Kuwano, K., and Ochiya, T. (2014). Intercellular communication by extracellular vesicles and their microRNAs in asthma. Clin. Ther. 36, 873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gao, J., Dennis, J. E., Muzic, R. F., Lundberg, M., and Caplan, A. I. (2001). The dynamic in vivo distribution of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after infusion. Cells Tissues Organs 169, 12–20. doi: 10.1159/000047856

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Gao, Q., Katakowski, M., Chen, X., Li, Y., and Chopp, M. (2005). Human marrow stromal cells enhance connexin43 gap junction intercellular communication in cultured astrocytes. Cell Transplant. 14, 109–117. doi: 10.3727/000000005783983205

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gao, Q., Li, Y., Shen, L., Zhang, J., Zheng, X., Qu, R., et al. (2008). Bone marrow stromal cells reduce ischemia-induced astrocytic activation in vitro. Neuroscience 152, 646–655. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.069

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gatti, S., Bruno, S., Deregibus, M. C., Sordi, A., Cantaluppi, V., Tetta, C., et al. (2011). Microvesicles derived from human adult mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischaemia-reperfusion-induced acute and chronic kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 26, 1474–1483. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr015

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gheldof, D., Mullier, F., Chatelain, B., Dogne, J. M., and Chatelain, C. (2013). Inhibition of tissue factor pathway inhibitor increases the sensitivity of thrombin generation assay to procoagulant microvesicles. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 24, 567–572. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328360a56e

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Harfe, B. D., McManus, M. T., Mansfield, J. H., Hornstein, E., and Tabin, C. J. (2005). The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

He, J., Wang, Y., Sun, S., Yu, M., Wang, C., Pei, X., et al. (2012). Bone marrow stem cells-derived microvesicles protect against renal injury in the mouse remnant kidney model. Nephrology (Carlton) 17, 493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2012.01589.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hergenreider, E., Heydt, S., Treguer, K., Boettger, T., Horrevoets, A. J., Zeiher, A. M., et al. (2012). Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 249–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2441

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Holtje, M., Djalali, S., Hofmann, F., Munster-Wandowski, A., Hendrix, S., Boato, F., et al. (2009). A 29-amino acid fragment of Clostridium botulinum C3 protein enhances neuronal outgrowth, connectivity, and reinnervation. FASEB J. 23, 1115–1126. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-116855

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Horstman, L. L., Jy, W., Minagar, A., Bidot, C. J., Jimenez, J. J., Alexander, J. S., et al. (2007). Cell-derived microparticles and exosomes in neuroinflammatory disorders. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 79, 227–268. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79010-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kapsimali, M., Kloosterman, W. P., De Bruijn, E., Rosa, F., Plasterk, R. H., and Wilson, S. W. (2007). MicroRNAs show a wide diversity of expression profiles in the developing and mature central nervous system. Genome Biol. 8, R173. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r173

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Katakowski, M., Buller, B., Zheng, X., Lu, Y., Rogers, T., Osobamiro, O., et al. (2013). Exosomes from marrow stromal cells expressing miR-146b inhibit glioma growth. Cancer Lett. 335, 201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.019

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, J., Inoue, K., Ishii, J., Vanti, W. B., Voronov, S. V., Murchison, E., et al. (2007a). A MicroRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science 317, 1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1140481

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, S. H., Bianco, N. R., Shufesky, W. J., Morelli, A. E., and Robbins, P. D. (2007b). Effective treatment of inflammatory disease models with exosomes derived from dendritic cells genetically modified to express IL-4. J. Immunol. 179, 2242–2249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2242

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, S. H., Lechman, E. R., Bianco, N., Menon, R., Keravala, A., Nash, J., et al. (2005). Exosomes derived from IL-10-treated dendritic cells can suppress inflammation and collagen-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 174, 6440–6448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6440

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Koh, W., Sheng, C. T., Tan, B., Lee, Q. Y., Kuznetsov, V., Kiang, L. S., et al. (2010). Analysis of deep sequencing microRNA expression profile from human embryonic stem cells derived mesenchymal stem cells reveals possible role of let-7 microRNA family in downstream targeting of hepatic nuclear factor 4 alpha. BMC Genomics 11(Suppl. 1), S6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-S1-S6

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kooijmans, S. A., Vader, P., Van Dommelen, S. M., Van Solinge, W. W., and Schiffelers, R. M. (2012). Exosome mimetics: a novel class of drug delivery systems. Int. J. Nanomedicine 7, 1525–1541. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29661

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kordelas, L., Rebmann, V., Ludwig, A. K., Radtke, S., Ruesing, J., Doeppner, T. R., et al. (2014). MSC-derived exosomes: a novel tool to treat therapy-refractory graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 28, 970–973. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.41

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lai, R. C., Arslan, F., Lee, M. M., Sze, N. S., Choo, A., Chen, T. S., et al. (2010). Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 4, 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lai, R. C., Tan, S. S., Teh, B. J., Sze, S. K., Arslan, F., De Kleijn, D. P., et al. (2012). Proteolytic potential of the MSC exosome proteome: implications for an exosome-mediated delivery of therapeutic proteasome. Int. J. Proteomics 2012, 971907. doi: 10.1155/2012/971907

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lakhal, S., and Wood, M. J. (2011). Exosome nanotechnology: an emerging paradigm shift in drug delivery: exploitation of exosome nanovesicles for systemic in vivo delivery of RNAi heralds new horizons for drug delivery across biological barriers. Bioessays 33, 737–741. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100076

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, C., Mitsialis, S. A., Aslam, M., Vitali, S. H., Vergadi, E., Konstantinou, G., et al. (2012). Exosomes mediate the cytoprotective action of mesenchymal stromal cells on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 126, 2601–2611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.114173

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, J. K., Park, S. R., Jung, B. K., Jeon, Y. K., Lee, Y. S., Kim, M. K., et al. (2013). Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells suppress angiogenesis by down-regulating VEGF expression in breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 8:e84256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084256

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, T. H., D'asti, E., Magnus, N., Al-Nedawi, K., Meehan, B., and Rak, J. (2011). Microvesicles as mediators of intercellular communication in cancer–the emerging science of cellular ‘debris’. Semin. Immunopathol. 33, 455–467. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0250-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, T., Yan, Y., Wang, B., Qian, H., Zhang, X., Shen, L., et al. (2013). Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver fibrosis. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 845–854. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0395

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, Y., Chen, J., Wang, L., Lu, M., and Chopp, M. (2001). Treatment of stroke in rat with intracarotid administration of marrow stromal cells. Neurology 56, 1666–1672. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.12.1666

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liang, X., Ding, Y., Zhang, Y., Tse, H. F., and Lian, Q. (2014). Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal Stem cell-based therapy: current status and perspectives. Cell Transplant. 23, 1045–1059. doi: 10.3727/096368913X667709

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lim, L. P., Lau, N. C., Garrett-Engele, P., Grimson, A., Schelter, J. M., Castle, J., et al. (2005). Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433, 769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lim, L. P., Lau, N. C., Weinstein, E. G., Abdelhakim, A., Yekta, S., Rhoades, M. W., et al. (2003). The microRNAs of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 17, 991–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.1074403

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, F. J., Lim, K. Y., Kaur, P., Sepramaniam, S., Armugam, A., Wong, P. T., et al. (2013). microRNAs involved in regulating spontaneous recovery in embolic stroke model. PLoS ONE 8:e66393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066393

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lu, D., Li, Y., Mahmood, A., Wang, L., Rafiq, T., and Chopp, M. (2002). Neural and marrow-derived stromal cell sphere transplantation in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 97, 935–940. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.4.0935

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lusardi, T. A., Murphy, S. J., Phillips, J. I., Chen, Y., Davis, C. M., Young, J. M., et al. (2014). MicroRNA responses to focal cerebral ischemia in male and female mouse brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7:11. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lv, H., Zhang, S., Wang, B., Cui, S., and Yan, J. (2006). Toxicity of cationic lipids and cationic polymers in gene delivery. J. Control. Release 114, 100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.014

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mahmood, A., Lu, D., and Chopp, M. (2004). Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 21, 33–39. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meckes, D. G. Jr. Gunawardena, H. P., Dekroon, R. M., Heaton, P. R., Edwards, R. H., Ozgur, S., et al. (2013). Modulation of B-cell exosome proteins by gamma herpesvirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2925–E2933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303906110

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mignot, G., Roux, S., Thery, C., Segura, E., and Zitvogel, L. (2006). Prospects for exosomes in immunotherapy of cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 10, 376–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00406.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Momen-Heravi, F., Balaj, L., Alian, S., Mantel, P. Y., Halleck, A. E., Trachtenberg, A. J., et al. (2013). Current methods for the isolation of extracellular vesicles. Biol. Chem. 394, 1253–1262. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0141

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Montecalvo, A., Larregina, A. T., Shufesky, W. J., Stolz, D. B., Sullivan, M. L., Karlsson, J. M., et al. (2012). Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 119, 756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mor, E., Cabilly, Y., Goldshmit, Y., Zalts, H., Modai, S., Edry, L., et al. (2011). Species-specific microRNA roles elucidated following astrocyte activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 3710–3723. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1325

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Olde Loohuis, N. F., Kos, A., Martens, G. J., Van Bokhoven, H., Nadif Kasri, N., and Aschrafi, A. (2012). MicroRNA networks direct neuronal development and plasticity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 89–102. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0788-1

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ono, M., Kosaka, N., Tominaga, N., Yoshioka, Y., Takeshita, F., Takahashi, R. U., et al. (2014). Exosomes from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells contain a microRNA that promotes dormancy in metastatic breast cancer cells. Sci. Signal. 7, ra63. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005231

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Park, J. E., Tan, H. S., Datta, A., Lai, R. C., Zhang, H., Meng, W., et al. (2010). Hypoxic tumor cell modulates its microenvironment to enhance angiogenic and metastatic potential by secretion of proteins and exosomes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1085–1099. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900381-MCP200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Qu, R., Li, Y., Gao, Q., Shen, L., Zhang, J., Liu, Z., et al. (2007). Neurotrophic and growth factor gene expression profiling of mouse bone marrow stromal cells induced by ischemic brain extracts. Neuropathology 27, 355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2007.00792.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Record, M., Carayon, K., Poirot, M., and Silvente-Poirot, S. (2014). Exosomes as new vesicular lipid transporters involved in cell-cell communication and various pathophysiologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1841, 108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.10.004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reis, L. A., Borges, F. T., Simoes, M. J., Borges, A. A., Sinigaglia-Coimbra, R., and Schor, N. (2012). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells repaired but did not prevent gentamicin-induced acute kidney injury through paracrine effects in rats. PLoS ONE 7:e44092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044092

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roccaro, A. M., Sacco, A., Maiso, P., Azab, A. K., Tai, Y. T., Reagan, M., et al. (2013). BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 1542–1555. doi: 10.1172/JCI66517

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sano, S., Izumi, Y., Yamaguchi, T., Yamazaki, T., Tanaka, M., Shiota, M., et al. (2014). Lipid synthesis is promoted by hypoxic adipocyte-derived exosomes in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 445, 327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.183

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schrier, S. L., Godin, D., Gould, R. G., Swyryd, B., Junga, I., and Seeger, M. (1971). Characterization of microvesicles produced by shearing of human erythrocyte membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 233, 26–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(71)90354-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, L. H., Li, Y., and Chopp, M. (2010). Astrocytic endogenous glial cell derived neurotrophic factor production is enhanced by bone marrow stromal cell transplantation in the ischemic boundary zone after stroke in adult rats. Glia 58, 1074–1081. doi: 10.1002/glia.20988

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, L. H., Li, Y., Gao, Q., Savant-Bhonsale, S., and Chopp, M. (2008). Down-regulation of neurocan expression in reactive astrocytes promotes axonal regeneration and facilitates the neurorestorative effects of bone marrow stromal cells in the ischemic rat brain. Glia 56, 1747–1754. doi: 10.1002/glia.20722

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, L. H., Xin, H., Li, Y., Zhang, R. L., Cui, Y., Zhang, L., et al. (2011b). Endogenous tissue plasminogen activator mediates bone marrow stromal cell-induced neurite remodeling after stroke in mice. Stroke 42, 459–464. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593863

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shimbo, K., Miyaki, S., Ishitobi, H., Kato, Y., Kubo, T., Shimose, S., et al. (2014). Exosome-formed synthetic microRNA-143 is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and inhibits their migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 445, 381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Spees, J. L., Olson, S. D., Ylostalo, J., Lynch, P. J., Smith, J., Perry, A., et al. (2003). Differentiation, cell fusion, and nuclear fusion during ex vivo repair of epithelium by human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2397–2402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437997100

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tan, C. Y., Lai, R. C., Wong, W., Dan, Y. Y., Lim, S. K., and Ho, H. K. (2014). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote hepatic regeneration in drug-induced liver injury models. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 5, 76. doi: 10.1186/scrt465

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Thery, C., Regnault, A., Garin, J., Wolfers, J., Zitvogel, L., Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P., et al. (1999). Molecular characterization of dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Selective accumulation of the heat shock protein hsc73. J. Cell Biol. 147, 599–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.599

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Timmers, L., Lim, S. K., Arslan, F., Armstrong, J. S., Hoefer, I. E., Doevendans, P. A., et al. (2007). Reduction of myocardial infarct size by human mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium. Stem Cell Res. 1, 129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.02.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Timmers, L., Lim, S. K., Hoefer, I. E., Arslan, F., Lai, R. C., Van Oorschot, A. A., et al. (2011). Human mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improves cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. 6, 206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.01.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tomasoni, S., Longaretti, L., Rota, C., Morigi, M., Conti, S., Gotti, E., et al. (2013). Transfer of growth factor receptor mRNA via exosomes unravels the regenerative effect of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 22, 772–780. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0266

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turturici, G., Tinnirello, R., Sconzo, G., and Geraci, F. (2014). Extracellular membrane vesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication: advantages and disadvantages. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 306, C621–C633. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Valadi, H., Ekstrom, K., Bossios, A., Sjostrand, M., Lee, J. J., and Lotvall, J. O. (2007). Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Villarroya-Beltri, C., Gutierrez-Vazquez, C., Sanchez-Cabo, F., Perez-Hernandez, D., Vazquez, J., Martin-Cofreces, N., et al. (2013). Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat. Commun. 4, 2980. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3980

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wang, J., Hendrix, A., Hernot, S., Lemaire, M., De Bruyne, E., Van Valckenborgh, E., et al. (2014). Bone marrow stromal cell-derived exosomes as communicators in drug resistance in multiple myeloma cells. Blood 124, 555–566. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-562439

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Chopp, M., Shen, L. H., Zhang, R. L., Zhang, L., Zhang, Z. G., et al. (2013a). Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells decrease transforming growth factor beta1 expression in microglia/macrophages and down-regulate plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 expression in astrocytes after stroke. Neurosci. Lett. 542, 81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.02.046

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Li, Y., Buller, B., Katakowski, M., Zhang, Y., Wang, X., et al. (2012). Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-133b from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells to neural cells contributes to neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells 30, 1556–1564. doi: 10.1002/stem.1129

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Li, Y., Chen, X., and Chopp, M. (2006). Bone marrow stromal cells induce BMP2/4 production in oxygen-glucose-deprived astrocytes, which promotes an astrocytic phenotype in adult subventricular progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 83, 1485–1493. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20834

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Li, Y., Cui, Y., Yang, J. J., Zhang, Z. G., and Chopp, M. (2013b). Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 1711–1715. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.152

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Li, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Shang, X., Cui, Y., et al. (2013c). MiR-133b promotes neural plasticity and functional recovery after treatment of stroke with multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in rats via transfer of exosome-enriched extracellular particles. Stem Cells 31, 2737–2746. doi: 10.1002/stem.1409

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Li, Y., Shen, L. H., Liu, X., Hozeska-Solgot, A., Zhang, R. L., et al. (2011). Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells increase tPA expression and concomitantly decrease PAI-1 expression in astrocytes through the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway after stroke (in vitro study). J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 2181–2188. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.116

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xin, H., Li, Y., Shen, L. H., Liu, X., Wang, X., Zhang, J., et al. (2010). Increasing tPA activity in astrocytes induced by multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells facilitate neurite outgrowth after stroke in the mouse. PLoS ONE 5:e9027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009027

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xu, J., Liu, X., Chen, J., Zacharek, A., Cui, X., Savant-Bhonsale, S., et al. (2010). Cell-cell interaction promotes rat marrow stromal cell differentiation into endothelial cell via activation of TACE/TNF-alpha signaling. Cell Transplant. 19, 43–53. doi: 10.3727/096368909X474339

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yeo, R. W., Lai, R. C., Zhang, B., Tan, S. S., Yin, Y., Teh, B. J., et al. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cell: an efficient mass producer of exosomes for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65, 336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yu, L., Yang, F., Jiang, L., Chen, Y., Wang, K., Xu, F., et al. (2013). Exosomes with membrane-associated TGF-beta1 from gene-modified dendritic cells inhibit murine EAE independently of MHC restriction. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 2461–2472. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243295

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yu, Y. M., Gibbs, K. M., Davila, J., Campbell, N., Sung, S., Todorova, T. I., et al. (2011). MicroRNA miR-133b is essential for functional recovery after spinal cord injury in adult zebrafish. Eur. J. Neurosci. 33, 1587–1597. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07643.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zacharek, A., Chen, J., Cui, X., Li, A., Li, Y., Roberts, C., et al. (2007). Angiopoietin1/Tie2 and VEGF/Flk1 induced by MSC treatment amplifies angiogenesis and vascular stabilization after stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 1684–1691. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600475

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, B., Wang, M., Gong, A., Zhang, X., Wu, X., Zhu, Y., et al. (2014). HucMSC-exosome mediated -Wnt4 signaling is required for cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. doi: 10.1002/stem.1771. [Epub ahead of print].

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, H. G., and Grizzle, W. E. (2014). Exosomes: a novel pathway of local and distant intercellular communication that facilitates the growth and metastasis of neoplastic lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.027

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, H., Huang, Z., Xu, Y., and Zhang, S. (2006b). Differentiation and neurological benefit of the mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into the rat brain following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol. Res. 28, 104–112. doi: 10.1179/016164106X91960

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, J., Brodie, C., Li, Y., Zheng, X., Roberts, C., Lu, M., et al. (2009). Bone marrow stromal cell therapy reduces proNGF and p75 expression in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurol. Sci. 279, 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.033

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, J., Li, Y., Lu, M., Cui, Y., Chen, J., Noffsinger, L., et al. (2006c). Bone marrow stromal cells reduce axonal loss in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 84, 587–595. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20962

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, Y., Xu, H., Xu, W., Wang, B., Wu, H., Tao, Y., et al. (2013). Exosomes released by human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against cisplatin-induced renal oxidative stress and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 4, 34. doi: 10.1186/scrt194

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhu, Y. G., Feng, X. M., Abbott, J., Fang, X. H., Hao, Q., Monsel, A., et al. (2014). Human mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles for treatment of Escherichia coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. Stem Cells 32, 116–125. doi: 10.1002/stem.1504

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zomer, A., Vendrig, T., Hopmans, E. S., Van Eijndhoven, M., Middeldorp, J. M., and Pegtel, D. M. (2010). Exosomes: fit to deliver small RNA. Commun. Integr. Biol. 3, 447–450. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.5.12339

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: cell-based therapy, multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC), Exosome, microRNAs (miRNAs), bio-information transfer, stroke

Citation: Xin H, Li Y and Chopp M (2014) Exosomes/miRNAs as mediating cell-based therapy of stroke. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:377. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00377

Received: 30 July 2014; Accepted: 22 October 2014;

Published online: 10 November 2014.

Reviewed by:

Shaohua Yang, University of North Texas Health Science Center, USA

Bernd Giebel, University Hospital Essen, Germany

Copyright © 2014 Xin, Li and Chopp. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongqi Xin, Neurology Research, Henry Ford Hospital, Room 3013, Education and Research Building, 2799 W. Grand Boulevard, Detroit, MI 48202 USA e-mail:aG9uZ3FpQG5ldXJvLmhmaC5lZHU=;SFhpbjFAaGZocy5vcmc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.