Evidence for treatable inborn errors of metabolism in a cohort of 187 Greek patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (original) (raw)

Introduction

Numerous pathologies (Fragile X, syndromes of congenital infection, vaccinations, perinatal damage, and others) have been discussed as potential etiologies associated with autistic behavior and/or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Mazzoko et al., 1998; Gallagher and Goodman, 2010), and an expanding literature has demonstrated more frequent associations between inborn errors of metabolisms (IEMs) and ASD (Weissman et al., 2008; Sempere et al., 2010). Recent reports have highlighted a growing association between ASDs and respiratory chain abnormalities, including complex III/IV deficiency and MELAS syndrome, as well as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (Guevara-Campos et al., 2010; Chauhan et al., 2011). Further, a number of reports suggest metabolic derangements in ASD patients that are suggestive of IEM, such as abnormalities of glucose oxidation and utilization, among others (Haznedar et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010). In these cases, however, it is difficult to conclusively identify whether the manifestation of ASD on the background of the IEM is a primary or secondary pathology. Despite the increased number of IEM, recent work (Schiff et al., 2010) suggested that a careful clinical evaluation is more crucial than systematic metabolic investigations but this aspect should be tested through a large population based prospective study assessing the benefits of routine metabolic screening in non-syndromic autistic spectrum disorders.

Greece represents a country for which a number of populations reside in relative geographic isolation. This is especially true for the Greek islands, where previous studies have documented a large number of patients for whom indeterminate neurological features associate with a small number of IEMs (Evangeliou et al., 2001). Many of these patients manifest features of ASD, occasionally associated with a positive family history and/or consanguinity. In order to extend our earlier work, we examined a cohort of these patients on the island of Crete in order to ascertain the incidence of IEMs and metabolic disturbances, and the corresponding link to ASD. The current report summarizes the results of our investigations.

Materials and Methods

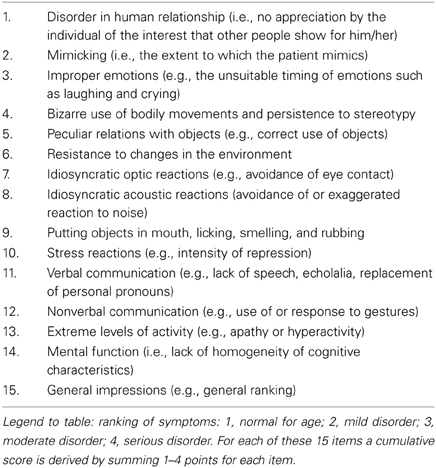

We evaluated 187 children (105 males, 82 females; ages 4–14 years) who presented with ASD. The differential diagnosis was based upon DSM-IV criteria for pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs; Kim et al., 2010; see also Table 1).

Table 1. Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) (Schopler et al., 1980).

Patients with identified ASD etiologies (e.g., perinatal damage, CNS infection, CNS tumor, or chromosomal abnormalities related to known neurogenetic disorders such as Angelman syndrome) were excluded from evaluation. Further, patients with otorhinal or ocular abnormalities, as well as failure to thrive, were also excluded.

At admission, we recorded detailed family histories (e.g., additional affected individuals, consanguinity, repetitive miscarriages, etc.) as well as dietary habits of the patients (symptoms following ingestion of certain foods and/or prolonged fasting, tendency to dietary avoidances). All subjects underwent detailed clinical and psychiatric examination, and anthropomorphic data was obtained. Laboratory investigations included: complete blood count, blood biochemical evaluations (electrolytes, glucose, transaminases, CPK, LDH, cholesterol, triglycerides, thyroid hormones), electrocardiogram (ECG), and electroencephalogram (EEG). These were followed by more specific examinations, including: serum amino acids, carnitine, urine purines and pyrimidines, urine amino and organic acids, urine mucopolysaccharides and oligosaccharides, cytogenetic analysis, and glucose loading test. For the latter, blood was obtained for determination of lactic acid, pyruvate, and β-hydroxybutyric acid (b-OH-b) following an 8 h fast, after which subjects received a 10% glucose bolus (2 g/kg of body weight, maximum 50 g). Sixty minutes post glucose administration, blood was obtained for determination of the same metabolites. In selected patients, more detailed analyses included lysosomal enzymology, guanidinoacetate-_n_-methyltransferase (GAMT) assay and biopsy of skeletal muscle for assessment of various mitochondrial enzymes.

Results

Confirmed Diagnoses

We identified two patients with Lesch Nyhan syndrome, two patients with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency, and a single patient with phenylketonuria. Thus, confirmed diagnoses in ASD patients for a known IEM was 2.7% of the total subject number investigated.

Biochemical Abnormalities Suggestive of IEM

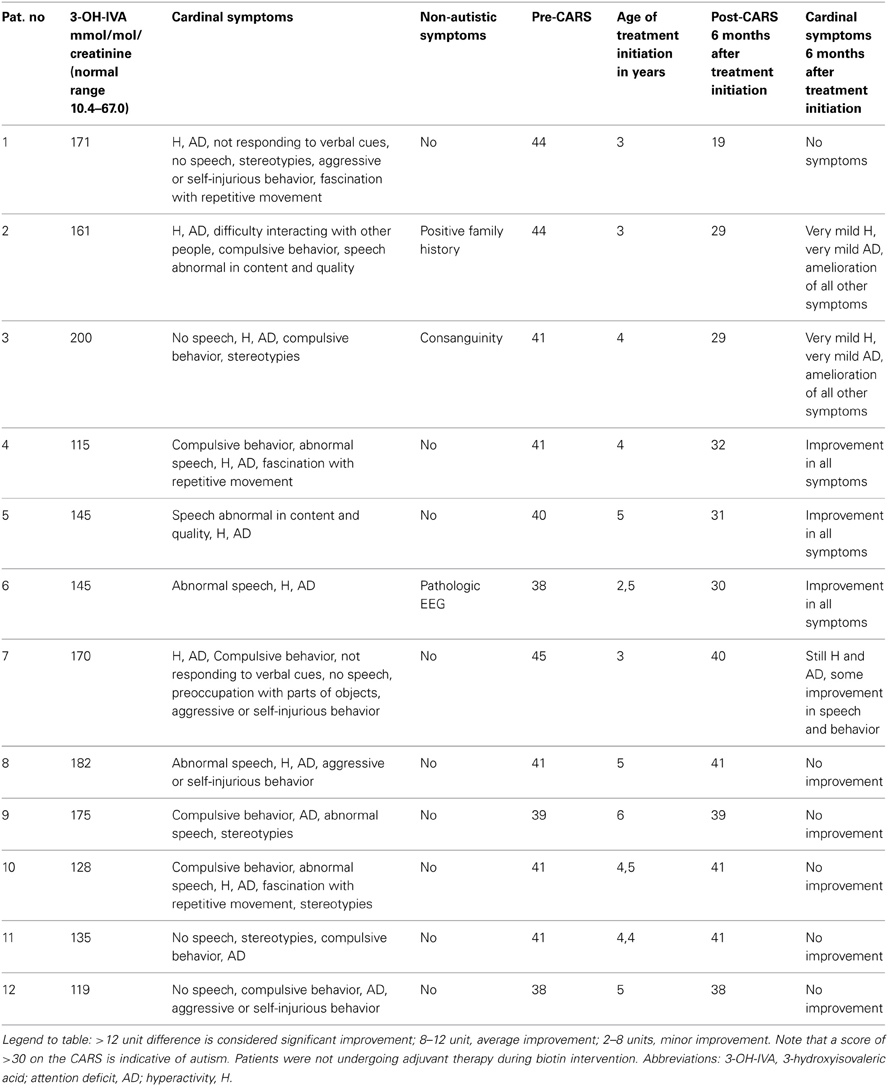

For 12/187 (7%) of patients, urinary 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid (3-OH-IVA) was elevated and sera methylcitrate and lactate levels were also elevated in two of these patients. Despite these biochemical abnormalities, defects in biotinidase, or holocarboxylase synthetase (Watanabe et al., 2005) could not be demonstrated in either sera or fibroblasts. Of interest, none of these 12 patients was undergoing valproate intervention, the latter a potential source of 3-OH-IVA elevation in urine (Silva et al., 2001). Despite an absence of confirmatory enzyme deficiencies in these 12 patients, we nonetheless opted to treat empirically with biotin for 3 weeks, 2 × 10 mg and then for 6 months at 2 × 5 mg, which led to a clear therapeutic benefit in 7/13 consisting of improvement in the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Table 2). For those benefiting from biotin intervention, the most impressive outcome centered on a 42 month-old boy whose severe ASD was completely ameliorated following biotin intervention. This patient was subsequently followed for 5 years, and cessation of biotin intervention (or placebo replacement) resulted in the rapid return of ASD-like symptomatology. This patient currently attends public school without any clinical sequelae and remains on biotin at 20 mg/d.

Table 2. ASD patients with increased urinary 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid and biotin supplemented.

Results of Diagnostic Loading Studies

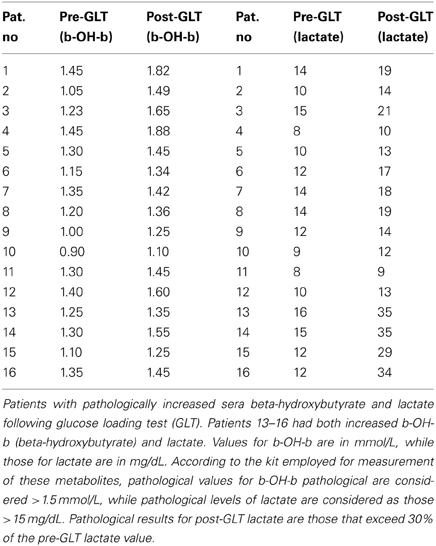

A glucose challenge was administered to all test subjects, revealing a pathological increase in sera b-OH-b in 16/187 subjects (Table 3) and elevated sera lactate in 18/187. These results for glucose loading pointed to mitochondrial disease, although confirmatory testing could not be undertaken due to a lack of monetary support for muscle biopsy from both parents and insurers.

Table 3. Evaluation of lactate and beta-hydroxybutyrate after glucose loading test.

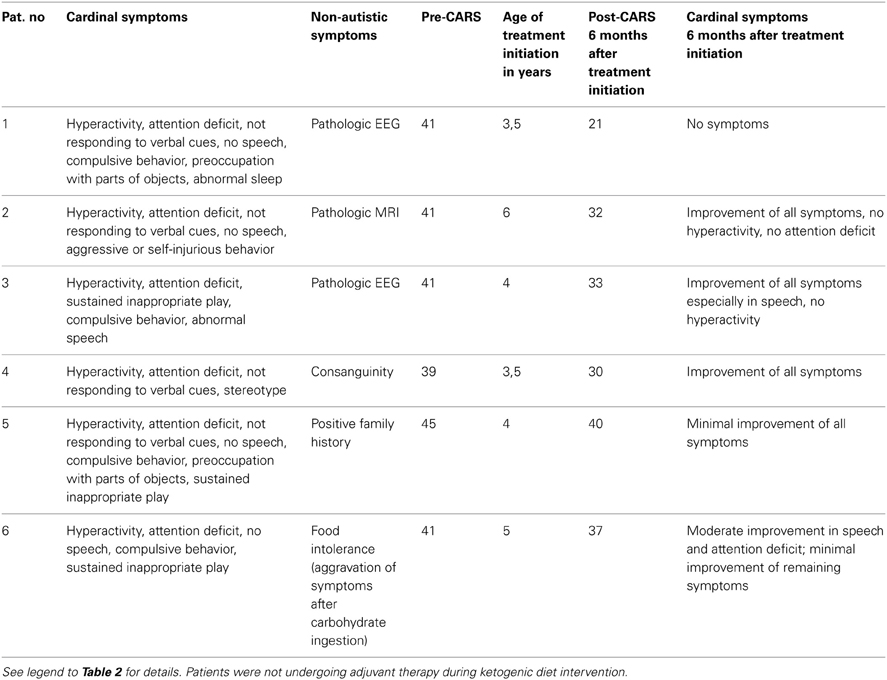

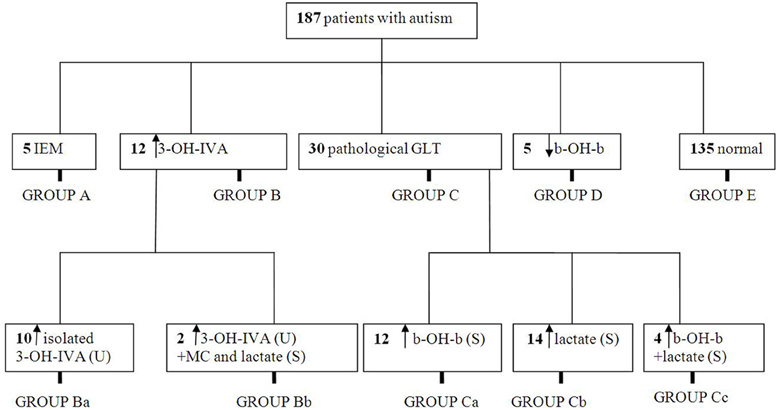

We instituted a ketogenic diet (KD) in 6/16 patients who had demonstrated a pathological increase in serum b-OH-b associated with glucose loading. Although our desire was to implement the KD in all 16 patients, it is a diet particularly challenging to implement in autistic patients, and we were only successful in six cases. One of these six patients showed a remarkable improvement in CARS scale (Table 4) and subsequently medications (risperidone and hydroxyzine) were stopped. This patient is currently attending a public elementary school without clinical problems. Clinical improvements in the remaining 5/6 patients were more subtle (Table 4). Additionally, for 5/178 patients, blood b-OH-b levels were significantly lower in comparison to control levels following a 12 h fast. Conversely, urine organic acid analysis and acylcarnitine evaluation in dried blood spots were normal for all of these patients, thus providing no evidence for a defect in beta-oxidation. An overview of abnormal biochemical and loading results is presented in Figure 1.

Table 4. ASD patients responsive to ketogenic diet implementation.

Figure 1. Summary of metabolic abnormalities in the patients evaluated in this study. Abbreviations: IEM, inborn errors of metabolism; 3-OH-IVA, 3 hydroxyisovaleric acid; GLT, glucose loading test; b-OH-b, β-hydroxybutyrate; MC, methylcitrate.

Family Histories, Clinical Findings, and Dietary Characteristics

Twenty-two of 178 test subjects had a family history that was positive for neurological disease. Additionally, 13/178 subjects had 1st, 2nd, or 3rd degree relatives with comparable symptoms, while other family members often suffered from other chronic neurological morbidity, including epilepsy, ataxia or mild to severe developmental delay. Consanguinity was confirmed in the parents of six patients (1st, 2nd and 3rd degree relatives). Unfortunately three of these families had children with symptomatology similar to that of the proband we investigated. Twelve of 178 patients had clear evidence of facial dysmorphia, including hypertelorism and low-set ears. With regard to diet, 26/178 subjects showed evidence of dietary intolerance. Of these, 5/26 patients (who also had abnormal glucose loading results) manifested exacerbation of symptoms during high carbohydrate intake. Similarly, three patients who demonstrated decreased blood ketone body production following a glucose bolus self-selected a low-fat diet, and high fat consumption correlated with deterioration in the clinical picture for one of these three, characterized by increased hyperactivity and stereotypies. Finally, 15/187 patients without biochemical abnormalities manifested food intolerance, and key clinical symptoms (hyperactivity, increased stereotypies, sleep disturbances) were exacerbated with high protein consumption.

Neuroimaging Abnormalities

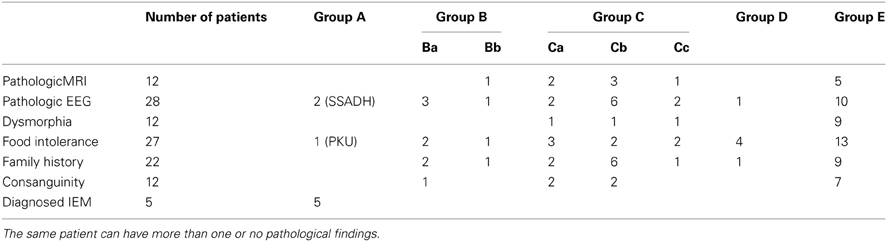

Twenty-five of 187 subjects manifested pathological EEG findings without seizures, the most common feature being beta-rhythms. Abnormalities of the MRI were found in 12/187 subjects, featuring primarily cerebellar hypoplasia and agenesis of the corpus callosum in the absence of specific structural abnormalities. Additionally, 7/187 patients without pathological biochemical findings suffered from epilepsy that was treated symptomatically with valproate (n = 3), carbamazepine (n = 3) and oxcarbazepine (n = 1). A comprehensive summary of findings for family history, consanguinity, dysmorphia, imaging abnormalities and dietary aversions is presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Distribution of pathological findings corresponding to subgroups depicted in Figure 1.

Discussion

A complex disorder associated with multifactorial inheritance, autism (or ASD; also pervasive developmental delay) is comprised of multiple phenotypic features, the most prominent of which are behavioral disturbances (e.g., obsessive compulsive disorder and/or highly ritualistic behavior) and primary disturbances of social skills, the latter prominent in adolescents and adults (Stokstad, 2001; Manzi et al., 2008; Kotulska and Jóźwiak, 2011). For most patients, the primary etiology remains undefined. Conversely, in a small subset of cases there is a clear genetic etiology, primarily those of a syndromic genetic disorder, including Fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis and others (Pickler and Elias, 2009; Toriello, 2012). Additionally, expanding research has revealed the presence of ASD in IEM, including phenylketonuria, disorders of mitochondrial metabolism (Weissman et al., 2008; Shoffner et al., 2010), defects in the metabolism of purines and pyrimidines, and disorders of cerebral glucose transport (Schaefer and Lutz, 2006; Schiff et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010). Of interest, in the rare disorder of GABA metabolism, SSADH deficiency, a major subset of confirmed adolescent patients suffer from extensive obsession compulsion, frequently characterized as ASD (Pearl et al., 2011).

In addition to the confirmed cases of IEM that were detected in the current report (5/178 cases), our cohort analyses included indirect evidence for IEM without confirmed diagnosis, including abnormal responses to glucose loading, response to KD (in the absence of clinical seizures) and responsiveness to pharmacological biotin administration. The response to biotin in a subset of our cohort, despite an absence of defined deficiencies in biotin-dependent biotinidase or multiple carboxylase enzymes, supports earlier findings in ASD cohorts revealing nutritional deficiencies including biotin (Main et al., 2010; Adams et al., 2011). From the biochemical perspective, it would seem logical to assume that biotin response and hyperexcretion of 3-OH-IVA in our cohort are correlated, most likely through biotin-dependent 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, but currently we have no clear etiology explaining the response to biotin.

To our knowledge, the existence of Lesch-Nyhan disease or SSADH deficiency has not been previously detected during screening of any ASD patient cohort. The rarity of both suggests that a more discrete screening for these disorders in the ASD population is warranted, at the very least in the Greek population. The finding of two cases of SSADH deficiency within 187 cases (>1%) is consistent with the expanding phenotypic observation of OCD in these patients (Vogel et al., 2012). The current report, therefore, may present some justification for the concept of screening for SSADH deficiency in the autism and ASD populations, especially in those populations in which autosomal recessive disorders are expected to have increased prevalence.

The current report represents only the second large scale evaluation of ASD patients for the presence of IEMs. Schiff et al. (2011) broadly screened 274 ASD patients for the presence of IEM, identifying two cases. These included a case of non-specific urinary creatine excretion and a patient with persistent 3-methylglutaconic aciduria, or less than 1% yield in their patient cohort. Neither Schiff's report nor ours positively identified patients with mitochondrial disease, creatine transport defects, glucose transport defect or others (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) which have been previously documented in ASD patients (Connolly et al., 2010; Guevara-Campos et al., 2010). This may simply reflect the ethnicity of the cohorts evaluated, including France and Greece, where incidence/prevalence of various IEMs will be quite different. Other investigators have recommended that care be taken in considering screening for IEM in ASD patients (Wang et al., 2010), and Moss and Howlin (2009) have appropriately cautioned that correlation of behavioral similarities between ASD and those observed in genetically-determined syndromes (e.g., Fragile X, Angelman, etc.) be carefully interpreted. Nonetheless, our report suggests that further consideration be given to the selected analysis of IEM in ASD patients, and that those studies might benefit from the broadest coverage of ethnic and regional groups possible, especially in populations for whom recessive disorders have an increased incidence. Broad screening evaluations such as these might be justifiable in helping to identify genetic subsets of ASD, providing genetic counseling opportunities for affected families, and presenting treatment options for those disorders for which therapeutic options are available. Clearly, the key outcome of our investigation is the identification of biomarker (3-OH-IVA and b-OH-b) with therapeutic relevance (biotin, KD) for patients with ASD, suggesting that our results should be investigated in additional ASD cohorts.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adams, J. B., Audhya, T., McDonough-Means, S., Rubin, R. A., Quig, D., Geis, E., et al. (2011). Nutritional and metabolic status of children with autism vs. neurotypical children, and the association with autism severity. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 8, 34. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-34

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Chauhan, A., Gu, F., Essa, M. M., Wegiel, J., Kaur, K., Brown, W. T., et al. (2011). Brain region-specific deficit in mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in children with autism. J. Neurochem. 117, 209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07189.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Connolly, B. S., Feigenbaum, A. S., Robinson, B. H., Dipchand, A. I., Simon, D. K., and Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2010). MELAS syndrome, cardiomyopathy, rhabdomyolysis, and autism associated with the A3260G mitochondrial DNA mutation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 402, 443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.060

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Evangeliou, A., Lionis, C., Michailidou, H., Spilioti, M., Kanitsakis, A., Nikitakis, P., et al. (2001). A selective screening for inborn errors of metabolism: the primary care-based model in rural Crete. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 24, 877–880. doi: 10.1023/A:1013904627537

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Gallagher, C. M., and Goodman, M. S. (2010). Hepatitis B vaccination of male neonates and autism diagnosis, NHIS 1997–2002. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. A 73, 1665–1677. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2010.519317

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Guevara-Campos, J., González-Guevara, L., Briones, P., Loìpez-Gallardo, E., Bulaìn, N., Ruiz-Pesini, E.,et al. (2010). Autism associated to a deficiency of complexes III and IV of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Invest. Clin. 51, 423–431.

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text

Haznedar, M. M., Buchsbaum, M. S., Hazlett, E. A., LiCalzi, E. M., Cartwright, C., and Hollander, E. (2006). Volumetric analysis and three-dimensional glucose metabolic mapping of the striatum and thalamus in patients with autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 1252–1263. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1252

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Kim, S. M., Han, D. H., Lyoo, H. S., Min, K. J., Kim, K. H., and Renshaw, P. (2010). Exposure to environmental toxins in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Invest. 7, 122–127. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.122

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Main, P. A., Angley, M. T., Thomas, P., O'Doherty, C. E., and Fenech, M. (2010). Folate and methionine metabolism in autism: a systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 1598–1620. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Mazzoko, M. M., Pulsifer, M., Fiumara, A., Cocuzza, M., Nigro, F., Incorpora, G., et al. (1998). Autistic behaviors among children with fragile X or Rett syndrome: implications for the classification of pervasive developmental disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 28, 321–328. doi: 10.1023/A:1026012703449

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Moss, J., and Howlin, P. (2009). Autism spectrum disorders in genetic syndromes: implications for diagnosis, intervention and understanding the wider autism spectrum disorder population. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 53, 852–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01197.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Pearl, P. L., Shukla, L., Theodore, W. H., Jakobs, C., and Gibson, K. M. (2011). Epilepsy in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, a disorder of GABA metabolism. Brain Dev. 33, 796–805. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.04.013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Schaefer, G. B., and Lutz, R. E. (2006). Diagnostic yield in the clinical genetic evaluation of autism spectrum disorders. Genet. Med. 8, 549–556.

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text

Schiff, M., Benoist, J. F., Aïssaoui, S., Boepsflug-Tanguy, O., Mouren, M.-C., de Baulny, H. O., et al. (2011). Should metabolic diseases be systematically screened in nonsyndromic autism spectrum disorders? PLoS ONE 6:e21932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021932

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., De Vellis, R. F., and Daly, K. (1980). Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 10, 91–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02408436

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Sempere, A., Arias, A., Farré, G. Garciìa-Villoria, J., Rodriìguez-Pombo, P., Desviat, L. R., et al. (2010). Study of inborn errors of metabolism in urine from patients with unexplained mental retardation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 33, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-9004-y

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Shoffner, J., Hyams, L., Langley, G. N., Cossette, S., Mylacraine, L., Dale, J., et al. (2010). Fever plus mitochondrial disease could be risk factors for autistic regression. J. Child Neurol. 25, 429–434. doi: 10.1177/0883073809342128

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Silva, M. F., Selhorst, J., Overmars, H., van Gennip, A. H., Maya, M., Wanders, R. J., et al. (2001). Characterization of plasma acylcarnitines in patients under valproate monotherapy using ESI-MS/MS. Clin. Biochem. 34, 635–638. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9120(01)00272-7

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Vogel, K. R., Pearl, P. L., Theodore, W. H., McCarter, R. C., Jakobs, C., and Gibson, K. M. (2012). Thirty years beyond discovery-Clinical trials in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, a disorder of GABA metabolism. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 36, 401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9499-5

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Wang, L., Angley, M. T., Sorich, M. J., Young, R. L., McKinnon, R. A., and Gerber, J. P. (2010). Is there a role for routinely screening children with autism spectrum disorder for creatine deficiency syndrome? Autism Res. 3, 268–272. doi: 10.1002/aur.145

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Watanabe, T., Oguchi, K., Ebara, S., and Fukui, T. (2005). Measurement of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid in urine of biotin-deficient infants and mice by HPLC. J. Nutr. 135, 615–618.

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text

Weissman, J. R., Kelley, R. I., Bauman, M. L., Cohen, B. H., Murray, K. F., Mitchell, R. L., et al. (2008). Mitochondrial disease in autism spectrum disorder patients: a cohort analysis. PLoS ONE 3:e3815. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003815

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text

Zhao, Y., Fung, C., Shin, D., Shin, B. C., Thamotharan, S., Sankar, R., et al. (2010). Neuronal glucose transporter isoform 3 deficient mice demonstrate features of autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Psychiatr. 15, 286–299. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.51