Frontiers | Role of Glia in Stress-Induced Enhancement and Impairment of Memory (original) (raw)

REVIEW article

Front. Integr. Neurosci., 11 January 2016

This article is part of the Research Topic All 3 types of glial cells are important for memory formation View all 16 articles

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA

- 2R.S. Dow Neurobiology Department, Legacy Research Institute, Portland, OR, USA

- 3Behavioral Neuroscience and Biology, University at Albany, Albany, NY, USA

Both acute and chronic stress profoundly affect hippocampally-dependent learning and memory: moderate stress generally enhances, while chronic or extreme stress can impair, neural and cognitive processes. Within the brain, stress elevates both norepinephrine and glucocorticoids, and both affect several genomic and signaling cascades responsible for modulating memory strength. Memories formed at times of stress can be extremely strong, yet stress can also impair memory to the point of amnesia. Often overlooked in consideration of the impact of stress on cognitive processes, and specifically memory, is the important contribution of glia as a target for stress-induced changes. Astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes all have unique contributions to learning and memory. Furthermore, these three types of glia express receptors for both norepinephrine and glucocorticoids and are hence immediate targets of stress hormone actions. It is becoming increasingly clear that inflammatory cytokines and immunomodulatory molecules released by glia during stress may promote many of the behavioral effects of acute and chronic stress. In this review, the role of traditional genomic and rapid hormonal mechanisms working in concert with glia to affect stress-induced learning and memory will be emphasized.

Introduction

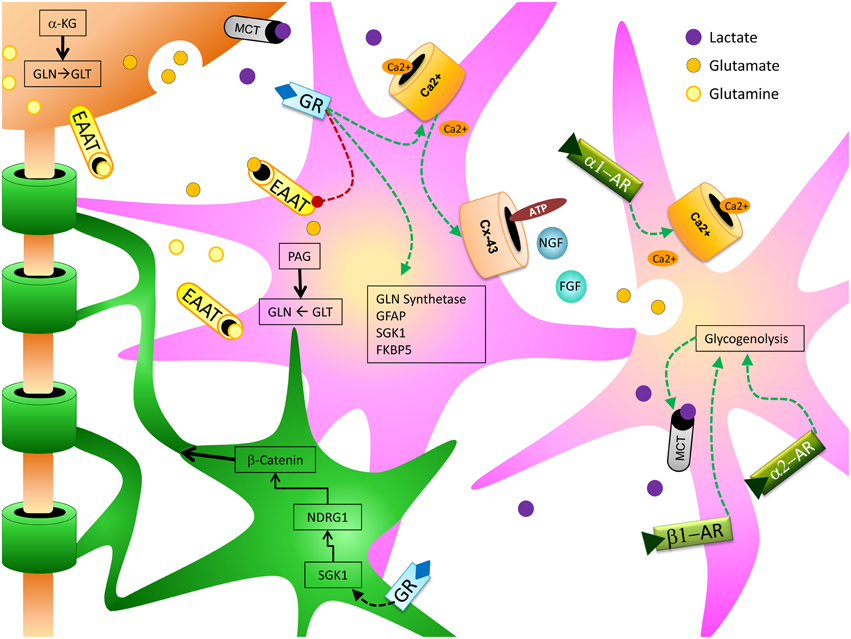

Over the past several years, consensus on the role of glia in cognitive function has shifted from viewing them as primarily supportive of neuronal actions to recognizing them as critical players in neural function and behaviors such as learning and memory (Fields et al., 2014) (Figure 1). Astrocytes exert a variety of influences on neural processes critical for memory, including regulation of extracellular K+ concentration, provision of metabolic support (i.e., glucose and/or lactate) to neurons, and recycling of glutamate and GABA (Moraga-Amaro et al., 2014). Ramified (previously known as “resting”) microglia can control synaptic plasticity through release of several different cytokines that can modulate memory (Morris et al., 2013). An expanding field of research demonstrates that other types of glia, such as oligodendrocytes, can also influence processes underlying learning and memory (Fields et al., 2014). Conversely, stress can have a profound impact on glial structure and function (particularly astrocytes and microglia), which may affect the glial contribution to learning and memory. The impact of stress and stress-associated molecules, such as glucocorticoids (GCs) and norepinephrine (NE), on glial function has been the target of substantial investigation (Jauregui-Huerta et al., 2010). Many of the effects that glia exert on memory following stress may be mediated through neuroinflammatory processes (Frank et al., 2012), and the interaction between glia and stress hormones is likely to be bidirectional: many neuroimmune molecules released by glia, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6, can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) (Dinan and Cryan, 2012).

Figure 1. Depicts the relationship between stress hormone effects on astrocytes (pink) and oligodendrocytes (green) and how they can support and enhance neuronal (orange) function to produce cognitive enhancing effects.

This review focuses on the specifics of interactions between stress hormones and glia, and the impact that these interactions have on learning and memory primarily via actions in the hippocampus.

Stress Axis Overview

The HPA axis is the canonical regulatory system for stress hormones. Immediately following exposure to a stressor, epinephrine is secreted from the adrenal medulla and triggers a central stress response via stimulation of NE release from the locus coeruleus (LC) to multiple areas of the brain, including the hippocampus (Womble et al., 1980; Wong et al., 2012). NE in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) then prompts the release of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH). CRH and vasopressin promote secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary via pro-opiomelanocortin (Petrov et al., 1993). ACTH initiates the synthesis of GCs for release by the adrenal cortex. Whereas NE acts rapidly in the brain following release from the LC, GCs do not typically reach the brain for up to 10 min (Barbaccia et al., 2001), at which point they exert both signal transduction- and genomic-based effects in the brain (Salehi et al., 2010); these include feedback signaling in the hippocampus and other brain regions to negatively regulate the HPA axis and hence limit the neural impact of stress (Liberzon et al., 1999).

Importance of Stress to Learning and Memory

Acute stress can facilitate formation of highly salient and long-lasting memories, which in extreme cases may form the basis of post-traumatic stress disorder (Oitzl and de Kloet, 1992; Sandi and Rose, 1994a,b, 1997; Roozendaal et al., 1996; Sandi et al., 1997; Oitzl et al., 2001; Lupien et al., 2002a,b; Cahill and Alkire, 2003; Cahill et al., 2003). Increases in NE and GCs, either independently or to a greater extent together, act to increase integration of input from several regions [e.g., basal lateral amygdala (BLA), LC, cortex, PVN] whose outputs directly or indirectly converge on the hippocampus (de Kloet et al., 2005). Released early in the stress response, NE actions in the BLA are particularly important for enhanced memory consolidation following exposure to acute stress (Ferry and McGaugh, 1999; Hatfield and McGaugh, 1999; LaLumiere et al., 2003; Lalumiere and McGaugh, 2005). BLA lesions attenuate the procognitive effects of NE (Liang and McGaugh, 1983; Liang et al., 1990; Roozendaal and McGaugh, 1996), and administration of adrenergic antagonists, particularly β-adrenergic receptor (AR) antagonists to the amygdala (i) produces similar attenuation of stress enhanced memory and (ii) prevents GC-mediated increases in hippocampal-dependent learning (Liang et al., 1986; Quirarte et al., 1997; Roozendaal et al., 1999). Compared to the actions of NE in the BLA, direct effects of NE in the hippocampus are not as clear, although infusions of NE to the hippocampus can improve contextual fear learning (Yang and Liang, 2014). Again these effects appear to be dependent on β-AR activation, as propranolol administration prior to or following training diminished contextual fear performance (Stuchlik et al., 2009; Kabitzke et al., 2011).

The effects of elevated GCs on learning and memory are more complicated and time/dose sensitive than those of NE. Both mineralocorticoid (MRs) and glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) are present throughout the brain, and the hippocampus has the highest level of receptor co-localization (Sarrieau et al., 1984; Reul and de Kloet, 1985, 1986; Van Eekelen et al., 1988; Herman et al., 1989; Decavel and Van den Pol, 1990; Funder, 1994; Cullinan, 2000; Reul et al., 2000a,b; Barbaccia et al., 2001); consistent with this, GCs are potent modulators of hippocampal memory processes. Stress-mediated rises in GC levels following learning can improve memory formation, but proximate to recall GCs may impair memory retrieval (Oitzl and de Kloet, 1992; Kirschbaum et al., 1996; Sandi and Rose, 1997; Oitzl et al., 2001; Roozendaal, 2002; Joëls, 2006). GCs can also mask the mnemonic effects of NE when administered prior to NE (Borrell et al., 1984; Joels and de Kloet, 1989; Roozendaal, 2003; Richter-Levin, 2004). The effects of GCs on memory processing vary not only with the temporal relationship of increases in GCs to the event being remembered, but also according to the level of GC increase. The impact of GCs on the hippocampus (particularly CA1) follows an inverted-U-shaped dose-response curve (Joëls, 2006; Polman et al., 2013). Removal of GCs by adrenalectomy results in impaired consolidation, an effect that can be rescued by administering moderate doses of GCs (Joëls, 2006; Spanswick et al., 2011), so that low levels of GCs appear to mediate not only procognitive effects of moderate stress but also the formation of memories under baseline, non-stressed conditions. Moderate, physiological increases in GCs can improve cognitive processes, but very high elevations in GCs acutely impair hippocampal function (Salehi et al., 2010). Similarly, very high and/or prolonged GC exposure markedly impairs subsequent hippocampal function with results including cognitive deficits, hippocampal atrophy, metabolic dysfunction, and central insulin resistance (Sapolsky et al., 1985; Sapolsky, 1996; Willi et al., 2002; Joëls et al., 2004; Stranahan et al., 2008; Karatsoreos et al., 2010; Yun et al., 2010; Ye et al., 2011; Reagan, 2012).

Astrocytes are the most widely studied glial cell-type with regard to both memory processes and the effects of stress. It has been known for decades that chronic stress is associated with a decrease in hippocampal and prefrontal cortex volume (Fuchs and Flügge, 2003). More recent studies have shown that much of the brain volume reduction caused by chronic stress is accounted for by a large decrease in astrocytes, rather than neurons (Rajkowska and Miguel-Hidalgo, 2007). Similar outcomes of stress, and of elevated GCs in particular, have been observed in animal models: short-term stress increasing astrocyte volume (as measured by GFAP immunoreactivity), while chronic stress decreases astrocyte volume (Lambert et al., 2000; Jauregui-Huerta et al., 2010).

Glucocorticoid-specific Astrocytic Actions: Stress and Memory

Astrocytes can influence memory in a variety of ways including (i) control of glutamate reuptake, synthesis and metabolism, (ii) regulation of calcium dynamics, (iii) large-scale coordination of neural activity via release of gliotransmitters, (iv) regulation of blood flow and hence glucose supply, and (v) provision of lactate as a metabolic substrate for neurons (Sahlender et al., 2014). Both GRs and MRs are expressed by astrocytes, and GCs have potent effects on astrocytic function (Jauregui-Huerta et al., 2010). Hence, it follows that GC-mediated modulation of astrocyte activity would influence cognitive processes. Here, we will focus on the known impact of GCs on memory processes mediated by astrocytes.

Astrocytes play a key role in regulating glutamate metabolism and activity. Following neural release of glutamate into synapses, astrocytes can remove glutamate through glial-specific glutamate transporters and convert glutamate into glutamine. Glutamine can then be used as an energy substrate in astrocytes or exported to neurons, where it can be re-converted into glutamate (Schousboe et al., 1993). Many of the long-term effects of chronically elevated GCs have been linked to excitotoxicity; GC-mediated dysfunction in astrocytes may prevent optimal glutamate clearance and therefore promote excitotoxicity (Popoli et al., 2012). Moreover, GC-induced dysfunction of astrocytes may also affect calcium metabolism and regulation, which will also impair glutamate regulation and thus increase the risk of excitotoxicity. Indeed, an important candidate mechanism for transduction of mnemonic regulation by astrocytes is calcium signaling. Regulation of calcium release and sequestration is also affected by GCs and stress. In both neurons and astrocytes, GCs control calcium homeostasis and signaling (Simard et al., 1999; Chameau et al., 2007; Suwanjang et al., 2013). Activated GRs can increase mitochondrial buffering capacity, leading to a reduction in cytosolic calcium (Psarra and Sekeris, 2009), and GCs can increase astrocytic calcium waves (Simard et al., 1999). These effects feed back into regulation of glutamate, discussed above: astrocytic calcium signaling controls release of glutamate (Volterra and Meldolesi, 2005). Calcium influx in astrocytes promotes release of gliotransmitters, which can include amino and nucleic acids, ATP, growth factors, glutamate, and/or peptides (Parpura et al., 2010, 2011). Gliotransmitters have been associated with regulation of the multipartite synapse, where they regulate neural excitability and can hence modulate memory processing (Hassanpoor et al., 2014). Inhibition of gliotransmitter release by blocking Cx-43 hemichannels (which release gliotransmitters) in astrocytes prevents the formation of long-term fear memories (Stehberg et al., 2012).

Stress can affect a variety of growth factors involved in learning and memory. For example, nerve growth factor (NGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) are both increased following exposure to GCs or stress (Mocchetti et al., 1996; Molteni et al., 2001; Gubba et al., 2004; Chang et al., 2005; Kirby et al., 2013; Hashikawa et al., 2015). FGF in particular is critical for homeostatic regulation of astrocytes, and changes in FGF are largely responsible for the transition of astrocytes from a nonreactive to a reactive state (Kang et al., 2014a,b). These findings are intriguing because NE signaling can increase astrocyte reactivity (Griffith and Sutin, 1996); thus suppression of astrocyte reactivity by GC-induced release of FGF may moderate increased overall astrocyte reactivity following prolonged sympathetic activation. NGF has many roles, not limited to effects on glia; these include increasing both survival and differentiation of newly-maturing neurons and supporting hippocampal-dependent memory processes and cholinergic signaling (Chao, 2003; Mufson et al., 2003; Capsoni and Cattaneo, 2006; Schindowski et al., 2008; Aboulkassim et al., 2011).

GRs in the nucleus act as a transcription factor. Because different cell types have unique transcriptomes, it is worth discussing how GRs specifically influence gene transcription in astrocytes. In mature astrocytes GCs have been found to regulate a specific subset of genes that differs from that regulated in neurons. Early work demonstrated that transcription of glutamine synthetase and glial fibrillary acidic protein, both astrocyte-specific, is under GC-mediated control (Nichols et al., 1990; Laping et al., 1994), suggesting that both metabolic function and morphology of astrocytes can be influenced by GCs at the level of mRNA. Of the numerous genes affected by GCs in hippocampal astrocytes, some stand out as playing a prominent role in cognition and are under differential control by GCs based on dose/duration of exposure (Carter et al., 2013). Acute exposure to GCs, at doses sufficient to activate GRs, results in significantly increased astrocytic mRNA levels of adenosine 2b receptor, FK506 binding protein (FKBP5), pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4, and serum/glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-1 (Sgk1), while significantly decreasing early growth response protein 2 (Egr2) and wingless-related MMTV integration site 7a (Wnt7a). In contrast, chronic exposure to GCs produced effects that in some cases are opposite of the acute effects. Chronic GCs decrease hippocampal RNA expression of growth associated protein 43 (Gap43), histone deacetylase 7 (Hdac7), and synapsin II. Additionally, chronically elevated GCs decrease adenosine receptor 2b and Sgk1, while the effects of acute vs. chronic are the same for FKBP5 and Wnt7a. Similar effects were observed in the cortex, demonstrating that acute and chronic exposure to GCs have different effects on astrocytic gene expression (Carter et al., 2012, 2013) including that of several genes whose products are important in memory processing: in general, these changes are consistent with enhancement of memory processing after acute elevation in GCs but impairment after chronic GC elevation. Moreover, prolonged elevations in GCs can lead to a reduced number of astrocytes (Unemura et al., 2012). Given the data discussed in this review showing the importance of astrocytes in mediating neural processes critical for memory, it is likely that changes in gene expression and a reduction in astrocyte quantity and function following prolonged stress and GC exposure may underlie some of the cognitive deficits observed following long-term stress.

As noted, many of the astrocytic genes changed by GCs have products that are involved in memory processing. FKBP5 is particularly interesting as it can control stress reactivity (Schmidt et al., 2015). FKBP5 is a chaperone protein required to shuttle GRs to the nucleus (Binder, 2009). It has also been heavily implicated in early life stress programming, epigenetic regulation of stress responding (Klengel et al., 2013), and susceptibility to chronic stress later in life (Hartmann et al., 2012; Guidotti et al., 2013; Radley et al., 2013). Patients with PTSD have decreased FKBP5 expression, and successful cognitive-behavioral therapy in PTSD patients increases FKBP5 expression and hippocampal volume (Levy-Gigi et al., 2013). It is unclear, however, whether many of these effects of FKBP5 are mediated through glia or neurons. Sgk1 has an ever-growing body of evidence to indicate that it is integral to GC effects to enhance cognition, which includes actions to activate CREB and increase AMPAR and NMDAR receptors at the plasma membrane (Strutz-Seebohm et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Tai et al., 2009; Lang et al., 2010). Currently, it is unclear as to whether the pro-cognitive activities of Sgk1 are mediated by neurons or astrocytes. Future research should examine the specific role of Sgk1 in astrocyte function given the robust increase in astrocytic Sgk1 following both acute and chronic GCs (Carter et al., 2013).

A further mechanism by which astrocytes may contribute to learning and memory is via metabolism of glucose leading to export of lactate, which will both regulate cerebral blood flow and potentially provide metabolic support to active neurons (Iadecola and Nedergaard, 2007). Some data suggest that acquisition of long-term fear memories may require astrocytically-derived lactate (Suzuki et al., 2011). Intriguingly, it is unknown as to what extent stress-induced molecules such as GCs can affect efficacy of lactate export from astrocytes. Astrocytes form a functional unit with neurons and blood vessels, which has been referred to as the neurovascular unit (Iadecola and Nedergaard, 2007). Many neuroinflammatory molecules that are released during stress are known to affect the neurovascular unit, and can increase “leakiness” of the blood-brain barrier (Kröll et al., 2009). In the amygdala, GCs produced by chronic stress can impair efficacy of the neurovascular unit by preventing vasodilation in response to neural activity (Longden et al., 2014). It is currently unknown whether neurovascular units in other brain regions respond similarly/differently to that of the amygdala, but such effects are likely to markedly impact cognitive processing. As a side note, such effects are also important to consider when interpreting fMRI or PET studies in which patients may be stressed, which is likely to be the case in the majority of such studies.

Overall, GCs exert a variety of effects on astrocytic function, from acute effects via calcium dynamics and release of gliotransmitters to transcription-mediated events, neurovascular control, and regulation of glutamate metabolism and glucose flux.

Astrocyte-specific Noradrenergic Activities

Using rodents and chicks, respectively, Dr. Leif Hertz's and Dr. Marie Gibbs' groups have elucidated many roles for noradrenergic signaling in regulating astrocyte function and metabolism (Huang and Hertz, 1995; Hertz et al., 2007, 2010; Gibbs and Bowser, 2010). While most of this work has been aimed at unraveling cognitive aspects of astrocytic function under baseline conditions, these data can likely be extended to permit speculation on the impact of LC activation and subsequent NE release on cognitive function during stress.

Noradrenergic cell bodies are primarily located within the LC and project throughout the cerebral cortex, limbic system, and cerebellum (Swanson and Hartman, 1975), with prefrontal cortical and hippocampal regions receiving large amounts of noradrenergic innervation (Gibbs et al., 2010). A simplified primary function of LC-activation during stress may be to “boost brain power” and direct cognitive processes toward enhanced attention, improved vigilance, and a shift in memory processing toward retrieval of information relevant to the stressor (O'Donnell et al., 2012). NE may promote some of these cognitive effects via astrocytic release of glutamate, lactate production and transport to active neurons, and an increase in both glycogen metabolism and gliotransmitter release (O'Donnell et al., 2012; Moraga-Amaro et al., 2014): overall, one major effect is to increase glucose metabolism to meet the demands of cognitive processing. Hippocampal memory processes are well-established to be limited by glucose availability, and the procognitive effects of exogenous glucose administration have been suggested to be via glia rather than neurons (McNay and Gold, 2002).

NE acts via G-protein coupled receptors; α- and β- type 1 and 2 adrenergic receptors (ARs). Astrocytes primarily express β1, α1, and α2 (Hertz et al., 1984, 2010; Deecher et al., 1993). Like GCs, NE regulate astrocytic calcium signaling (Gibbs and Bowser, 2010): administration of the α1 agonist phenylephrine increases intracellular Ca2+, and similarly stimulation of the LC increases intracellular astrocytic Ca2+ via an α1-dependent mechanism (O'Donnell et al., 2012). Because NE activation during stress precedes GC activation, it is possible that the reduction in intracellular calcium and increased mitochondrial calcium buffering induced by GCs acts to control increases in intracellular Ca2+ caused by NE signaling to prevent overexcitation and/or apoptotic events.

NE also has effects on astrocytic metabolism, and effects of both α-receptor and β-receptor signaling on astrocytic metabolism have been documented (Subbarao and Hertz, 1990, 1991; Hutchinson et al., 2007, 2008; Gibbs et al., 2008). Activation of α2 receptors on astrocytes can both promote glycogen storage and increase astrocytic glycogen breakdown (Hertz et al., 2007). Astrocytic β-receptor-mediated glycogenolysis is more effective than α-receptor mediated glycogenolysis (Subbarao and Hertz, 1990). Astrocytic glycogenolysis is critical for glutamate cycling, as well as providing lactate that may be especially important as a rapidly-utilizable energy source during cognitive demand. Both α1- and α2 adrenergic signaling in astrocytes can increase oxidative metabolism including lactate production (Subbarao and Hertz, 1991). NE can also increase glutamine uptake in astrocytes, which is another important energy metabolite in astrocytes (Huang and Hertz, 1995). Because energy provision is a rate-limiting step in neural activity, the several actions of NE to increase metabolic support for both astrocytes and neurons are likely key to producing increased strength of memories formed at times of moderate stress (Osborne et al., 2015). The specificity of NE receptor subtypes found on astrocytes offers a potential target for therapies aimed at specifically modulating glial responses to stress, including treatments for stress-related disorders.

Microglial Impacts on Cognition

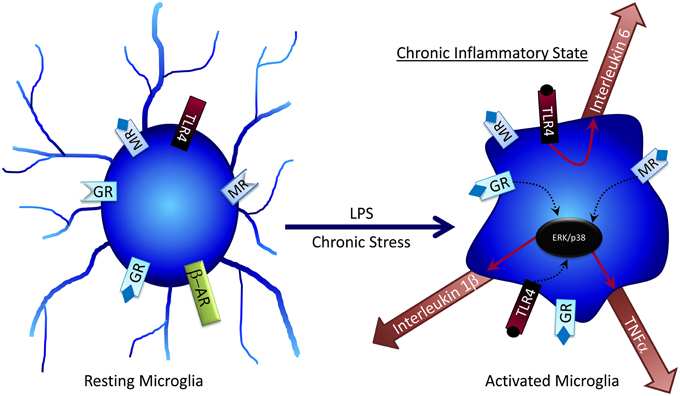

No longer regarded as solely an immune cell of the brain, several studies show that microglia are also involved in regulating neural activity (Thomas, 1992; Ilschner et al., 1996; Kettenmann, 2007), primarily through release of neuroimmune molecules such as cytokines that modulate surrounding neurons and astrocytes (Figure 2). Chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) promotes an increase in microglial proliferation and activation in a variety of brain regions including the hippocampus; however, following 5 weeks of CUS exposure microglial activity declines below baseline (Kreisel et al., 2014). Treatment with a variety of microglia-activating molecules such as endotoxin, macrophage colony-stimulating factor, or granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor can prevent CUS-induced depressive behaviors (Kreisel et al., 2014), suggesting that microglia may be key regulators of adaptation to chronic stress.

Figure 2. Microglia can become activated by factors such as LPS or chronic stress, where they become desensitized to the anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Activated microglia can release pro-inflammatory cytokines, which at high concentrations can have negative effects on cognitive processes.

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is perhaps the best-characterized cytokine released in response to stress. Following chronic mild stress, mice have impaired memory on both object location and object recognition memory. Cognitive impairments are accompanied by increased plasma IL-1β, plasma tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and IL-6 (Li et al., 2008). After chronic mild resident-defeat stress, a subset of rats that develop pro-depressive behaviors shows increased brain IL-β expression, and inhibition of brain IL-1β signaling prevents the pro-depressive symptoms (Wood et al., 2015). Independent of stress, studies have reported that IL-1β can impair memory, have no effect on memory, or enhance memory (Ross et al., 2003; Goshen et al., 2007; Huang and Sheng, 2010; Ben Menachem-Zidon et al., 2011; Bitzer-Quintero and González-Burgos, 2012; Pascual et al., 2012; Arisi, 2014; Jones et al., 2015), indicating that further work is needed.

Other microglial-released cytokines and immune molecules, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, can affect memory (Tonelli and Postolache, 2005; Nelson et al., 2013; Williamson and Bilbo, 2013; Arisi, 2014; Grinan-Ferre et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015). In general, effects of cytokines are highly dependent on timing, dose, and duration; but the potentially confounding effects of inflammation can make interpretation difficult and are a major contributing factor to every major neurological disease (Bibi et al., 2014; Daulatzai, 2014; Legido and Katsetos, 2014; Nisticò et al., 2014; Stuart and Baune, 2014; Patterson, 2015; Walker and Lue, 2015). Chronic stress, poor diets, and acute traumatic stress can all induce elevated cytokine release, negatively affecting learning outcomes (Boitard et al., 2014; Hsu et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2015; Yazir et al., 2015).

Important to discuss, as a component of microglial effects following stress, is the kynurenine pathway (KP). Following chronic stress, tryptophan can be directed toward the KP (Miura et al., 2008), primarily driven by cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3,-dioxygenase (IDO). In astrocytes, the KP increases production of the NMDA receptor agonist kynurenic acid; in microglia, the KP increases production of the NMDA receptor agonist quinolinic acid (Jo et al., 2015). Given the key role of NMDA receptors in hippocampal memory processing, it is not surprising that recent data suggests that activation of the KP can affect memory processes, and thus may be a novel pathway with importance for stress-related memory dysfunction (Heisler and O'Connor, 2015; Varga et al., 2015).

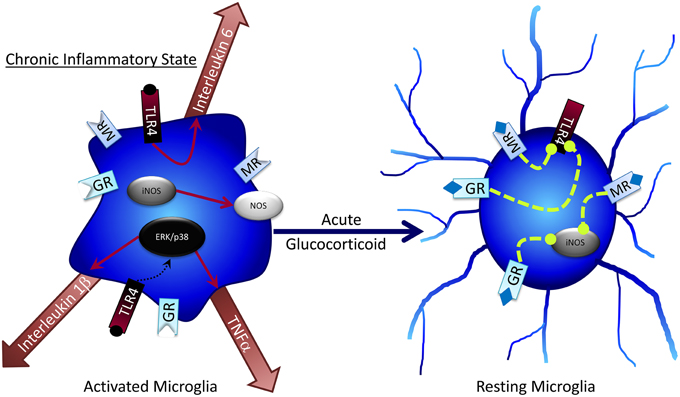

Microglia and Glucocorticoids

GCs have well-established anti-inflammatory effects that decrease microglial activation. GCs provide master control over several inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors (Figure 3). Microglia express both MRs and GRs (Sierra et al., 2008), and GCs can suppress central inflammation through microglia (Goujon et al., 1996; Kawai and Akira, 2010). GC administration to microglial cultures suppresses nitric oxide release by blocking the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, which likely leads to a reduction in microglial-mediated cell death (Drew and Chavis, 2000). In mice lacking functional GRs on microglia, lipopolysaccharide treatment (LPS; a treatment that produces “active” microglia) can increase neuroinflammation and neural toxicity relative to wildtype mice treated with LPS (Carrillo-de Sauvage et al., 2013). In other studies, GR antagonism attenuated the effects of LPS-induced microglial activation including CA1 pyramidal cell loss, JNK and p38 activation and decreased Akt and CREB phosphorylation (Espinosa-Oliva et al., 2011); taken together, these findings strongly support a role for GCs in modulating microglia function, but suggest that the impact of GCs may—as with e.g., astrocytes—be critically dependent on dosage and timing.

Figure 3. Acute glucocorticoid exposure can return activated microglia to resting states.

Chronic stressors can attenuate or prevent the anti-inflammatory effects of GR activation on microglia. Microglia can readily become sensitized to GC over-secretion to the point where GCs no longer prevent pro-inflammatory microglial activity, but rather promote it, as is the case in neurodegenerative disease and obesity (Munhoz et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2012; Dey et al., 2014). Understanding of the links between diet-induced obesity, cognitive dysfunction, and neurodegenerative disease continues to expand and now encompasses a greater role for microglia in these events. Sustained GC release and impaired HPA negative feedback are hallmarks of obesity and Type 2 Diabetes (Bruehl et al., 2009; de Guia et al., 2014; Paredes and Ribeiro, 2014; Martocchia et al., 2015), cognitive dysfunction (McEwen and Sapolsky, 1995; Dumas et al., 2010) and Alzheimer's disease (Notarianni, 2013). These pathological conditions are also characterized by increased cytokine release, inflammation, and microglial activation (Xiang et al., 2006; Rodriguez et al., 2010; Buckman et al., 2014; Erion et al., 2014; Hwang et al., 2014; Heneka et al., 2015; Kälin et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Ramos-Rodriguez et al., 2015).

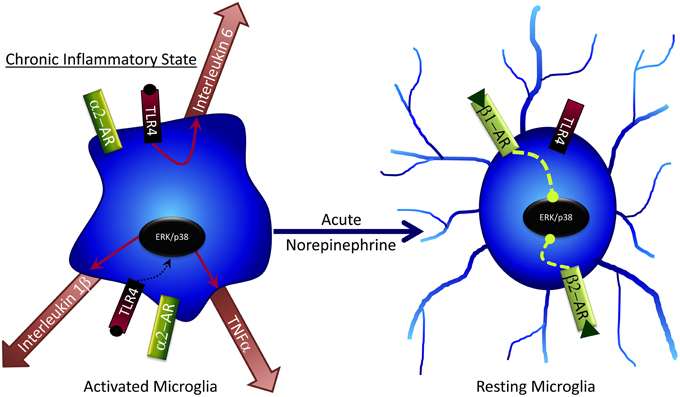

Microglia and Norepinephrine

NE has several effects on microglia that may contribute to cognitive deficits following stress (Figure 4). Generally, NE is capable of subduing inflammatory response genes in microglia and astrocytes (Hetier et al., 1991; Feinstein et al., 2002; Tynan et al., 2012), such as the major histocompatibility complex (Frohman et al., 1988), IL-1β (Ballestas and Benveniste, 1997), and TNF-α (Ballestas and Benveniste, 1997; Tynan et al., 2012) via β-AR activation. While in a “resting” phase, microglia predominately express β2 and β1 ARs (Tanaka et al., 2002), but this can change to α2 expression following inflammatory activation (i.e., during stress). Bath application of NE to brain slices results in microglial process retraction and potential reversal of stress-induced inflammation (Mori et al., 2002). NE can also attenuate microglial process extension mediated by the gliotransmitter ATP (Gyoneva and Traynelis, 2013); conversely, loss of NE decreases microglial migration to sites of inflammation (Heneka et al., 2010), confirming a key role for NE in microglial regulation. NE administration to cultured rat microglial cells decreases mRNA expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α (Mori et al., 2002). Although under normal, non-pathological conditions these pro-inflammatory factors can have important procognitive roles, in disease or chronic stress states their effects can become pathogenic and lead to impaired cognitive function and cell death. Therefore, NE may decrease pathogenic microglial action following stress (Heneka et al., 2010). Taken together with findings of GCs on inhibiting microglial activation, it is intriguing that both NE and GCs can suppress microglial activation amidst a milieu of pro-inflammatory stimuli (e.g., pro-inflammatory cytokines, increased BBB permeability, and immune cell influx into the brain) that occur following stress. These findings may suggest that NE and GCs, via glia, act in part as anti-inflammatory stimuli that prevent pathogenic inflammatory activity in the brain following stress; the impaired response to these hormones seen after chronic and/or very high stress may include diminished ability to protect against brain inflammation, with deleterious consequences.

Figure 4. Acute norepinephrine exposure can decrease release of cytokines by microglia via inhibition of ERK/p38 signaling.

Oligodendrocytes and Stress

While most attention in this field has been given to the impact of astrocytes and microglia on cognitive function, there is evidence that oligodendrocytes are also affected by stress and could modulate learning and memory. Oligodendrocytes' list of known functions extends beyond axon myelination, and now includes direct modulation of neuronal function (de Hoz and Simons, 2015).

Although stress and/or GC administration almost ubiquitously decreases neurogenesis (Anacker et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2013; Schoenfeld and Gould, 2013; Anacker, 2014; Chetty et al., 2014), stress has the opposite effect on oligodendrogenesis (Chetty et al., 2014). As with neurons, corticosterone increases activation of SGK1 in oligodendrocytes and subsequently induces abnormal morphological changes in arborization via NDRG1 and catenin signaling (Miyata et al., 2011). This increased arborization has been linked to increased depression-like behavior in stressed mice (Miyata et al., 2015). Other research suggests that GCs provide important survival signals that can aid oligodendrocyte and oligodendrocyte precursor survival against cytokine toxicity (Melcangi et al., 2000; Mann et al., 2008). Further investigation into the role oligodendrocytes play in cognition is required, both at baseline and after stress, but early evidence supports a vital function for this cell type in cognitive responses to stress.

Conclusion

Glia are increasingly recognized as critical regulators of cognitive processes; understanding of the multiple cell types involved in behavioral regulation and the molecular processes involved continues to expand. Glia are quickly becoming pharmacologically-relevant cellular targets for treatments of a variety of psychiatric disorders (Koyama, 2015) and offer a potential opportunity to regulate neural and cognitive responses to stress including treatment of stress-induced behavioral disorders. Such approaches are likely to take advantage of the potentially increased specificity offered by modulation mechanisms unique to glia rather than also affecting neurons.

Author Contributions

JP-L, DO, and EM all planned, drafted, and edited the manuscript.

Funding

Merlin Trust 2015 Excellence award to ECM; American Diabetes Association 7-12-BS-126 to ECM.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer Professor Leif Hertz and handling Editor Professor Ye Chen declared past collaboration and the handling Editor states that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

References

Aboulkassim, T., Tong, X. K., Tse, Y. C., Wong, T. P., Woo, S. B., Neet, K. E., et al. (2011). Ligand-dependent TrkA activity in brain differentially affects spatial learning and long-term memory. Mol. Pharmacol. 80, 498–508. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071332

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anacker, C. (2014). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression: behavioral implications and regulation by the stress system. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 18, 25–43. doi: 10.1007/7854_2014_275

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anacker, C., Cattaneo, A., Musaelyan, K., Zunszain, P. A., Horowitz, M., Molteni, R., et al. (2013). Role for the kinase SGK1 in stress, depression, and glucocorticoid effects on hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8708–8713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300886110

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arisi, G. M. (2014). Nervous and immune systems signals and connections: cytokines in hippocampus physiology and pathology. Epilepsy Behav. 38, 43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.01.017

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ballestas, M. E., and Benveniste, E. N. (1997). Elevation of cyclic AMP levels in astrocytes antagonizes cytokine-induced adhesion molecule expression. J. Neurochem. 69, 1438–1448. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041438.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ben Menachem-Zidon, O., Avital, A., Ben-Menahem, Y., Goshen, I., Kreisel, T., Shmueli, E. M., et al. (2011). Astrocytes support hippocampal-dependent memory and long-term potentiation via interleukin-1 signaling. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 1008–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.11.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bibi, F., Yasir, M., Sohrab, S. S., Azhar, E. I., Al-Qahtani, M. H., Abuzenadah, A. M., et al. (2014). Link between chronic bacterial inflammation and Alzheimer disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 13, 1140–1147. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666140917115741

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Binder, E. B. (2009). The role of FKBP5, a co-chaperone of the glucocorticoid receptor in the pathogenesis and therapy of affective and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(Suppl. 1), S186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.021

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bitzer-Quintero, O. K., and González-Burgos, I. (2012). Immune system in the brain: a modulatory role on dendritic spine morphophysiology? Neural Plast. 2012:348642. doi: 10.1155/2012/348642

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Boitard, C., Cavaroc, A., Sauvant, J., Aubert, A., Castanon, N., Layé, S., et al. (2014). Impairment of hippocampal-dependent memory induced by juvenile high-fat diet intake is associated with enhanced hippocampal inflammation in rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 40, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Borrell, J., de Kloet, E. R., and Bohus, B. (1984). Corticosterone decreases the efficacy of adrenaline to affect passive avoidance retention of adrenalectomized rats. Life Sci. 34, 99–104. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90336-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bruehl, H., Wolf, O. T., Sweat, V., Tirsi, A., Richardson, S., and Convit, A. (2009). Modifiers of cognitive function and brain structure in middle-aged and elderly individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Brain Res. 1280, 186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.032

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Buckman, L. B., Hasty, A. H., Flaherty, D. K., Buckman, C. T., Thompson, M. M., Matlock, B. K., et al. (2014). Obesity induced by a high-fat diet is associated with increased immune cell entry into the central nervous system. Brain Behav. Immun. 35, 33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.06.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cahill, L., and Alkire, M. T. (2003). Epinephrine enhancement of human memory consolidation: interaction with arousal at encoding. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 79, 194–198. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7427(02)00036-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cahill, L., Gorski, L., and Le, K. (2003). Enhanced human memory consolidation with post-learning stress: interaction with the degree of arousal at encoding. Learn. Mem. 10, 270–274. doi: 10.1101/lm.62403

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Capsoni, S., and Cattaneo, A. (2006). On the molecular basis linking Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) to Alzheimer's disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 26, 619–633. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9112-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carrillo-de Sauvage, M. Á., Maatouk, L., Arnoux, I., Pasco, M., Sanz Diez, A., Delahaye, M., et al. (2013). Potent and multiple regulatory actions of microglial glucocorticoid receptors during CNS inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 20, 1546–1557. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.108

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carter, B. S., Hamilton, D. E., and Thompson, R. C. (2013). Acute and chronic glucocorticoid treatments regulate astrocyte-enriched mRNAs in multiple brain regions in vivo. Front. Neurosci. 7:139. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00139

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carter, B. S., Meng, F., and Thompson, R. C. (2012). Glucocorticoid treatment of astrocytes results in temporally dynamic transcriptome regulation and astrocyte-enriched mRNA changes in vitro. Physiol. Genomics 44, 1188–1200. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00097.2012

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chameau, P., Qin, Y., Spijker, S., Smit, A. B., and Joëls, M. (2007). Glucocorticoids specifically enhance L-type calcium current amplitude and affect calcium channel subunit expression in the mouse hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 97, 5–14. doi: 10.1152/jn.00821.2006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chang, C. N., Yang, J. T., Lee, T. H., Cheng, W. C., Hsu, Y. H., and Wu, J. H. (2005). Dexamethasone enhances upregulation of nerve growth factor mRNA expression in ischemic rat brain. J. Clin. Neurosci. 12, 680–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.05.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chetty, S., Friedman, A. R., Taravosh-Lahn, K., Kirby, E. D., Mirescu, C., Guo, F., et al. (2014). Stress and glucocorticoids promote oligodendrogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 1275–1283. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.190

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cullinan, W. E. (2000). GABA(A) receptor subunit expression within hypophysiotropic CRH neurons: a dual hybridization histochemical study. J. Comp. Neurol. 419, 344–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(20000410)419:3<344::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-Z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Daulatzai, M. A. (2014). Chronic functional bowel syndrome enhances gut-brain axis dysfunction, neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment, and vulnerability to dementia. Neurochem. Res. 39, 624–644. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1266-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Deecher, D. C., Wilcox, B. D., Dave, V., Rossman, P. A., and Kimelberg, H. K. (1993). Detection of 5-hydroxytryptamine2 receptors by radioligand binding, northern blot analysis, and Ca2+ responses in rat primary astrocyte cultures. J. Neurosci. Res. 35, 246–256. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350304

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dey, A., Hao, S., Erion, J. R., Wosiski-Kuhn, M., and Stranahan, A. M. (2014). Glucocorticoid sensitization of microglia in a genetic mouse model of obesity and diabetes. J. Neuroimmunol. 269, 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.01.013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dinan, T. G., and Cryan, J. F. (2012). Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dumas, T. C., Gillette, T., Ferguson, D., Hamilton, K., and Sapolsky, R. M. (2010). Anti-glucocorticoid gene therapy reverses the impairing effects of elevated corticosterone on spatial memory, hippocampal neuronal excitability, and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 30, 1712–1720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4402-09.2010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Erion, J. R., Wosiski-Kuhn, M., Dey, A., Hao, S., Davis, C. L., Pollock, N. K., et al. (2014). Obesity elicits interleukin 1-mediated deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 34, 2618–2631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4200-13.2014

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Espinosa-Oliva, A. M., de Pablos, R. M., Villarán, R. F., Arguelles, S., Venero, J. L., Machado, A., et al. (2011). Stress is critical for LPS-induced activation of microglia and damage in the rat hippocampus. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 85–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.01.012

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Feinstein, D. L., Heneka, M. T., Gavrilyuk, V., Dello Russo, C., Weinberg, G., and Galea, E. (2002). Noradrenergic regulation of inflammatory gene expression in brain. Neurochem. Int. 41, 357–365. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(02)00049-9

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ferry, B., and McGaugh, J. L. (1999). Clenbuterol administration into the basolateral amygdala post-training enhances retention in an inhibitory avoidance task. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 72, 8–12. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3904

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fields, R. D., Araque, A., Johansen-Berg, H., Lim, S. S., Lynch, G., Nave, K. A., et al. (2014). Glial biology in learning and cognition. Neuroscientist 20, 426–431. doi: 10.1177/1073858413504465

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Frank, M. G., Thompson, B. M., Watkins, L. R., and Maier, S. F. (2012). Glucocorticoids mediate stress-induced priming of microglial pro-inflammatory responses. Brain Behav. Immun. 26, 337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.10.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Frohman, E. M., Vayuvegula, B., Gupta, S., and van den Noort, S. (1988). Norepinephrine inhibits gamma-interferon-induced major histocompatibility class II (Ia) antigen expression on cultured astrocytes via beta-2-adrenergic signal transduction mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 1292–1296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1292

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gibbs, M. E., Hutchinson, D. S., and Summers, R. J. (2008). Role of beta-adrenoceptors in memory consolidation: beta3-adrenoceptors act on glucose uptake and beta2-adrenoceptors on glycogenolysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 2384–2397. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301629

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gibbs, M. E., Hutchinson, D. S., and Summers, R. J. (2010). Noradrenaline release in the locus coeruleus modulates memory formation and consolidation; roles for alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors. Neuroscience 170, 1209–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.052

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goshen, I., Kreisel, T., Ounallah-Saad, H., Renbaum, P., Zalzstein, Y., Ben-Hur, T., et al. (2007). A dual role for interleukin-1 in hippocampal-dependent memory processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, 1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goujon, E., Parnet, P., Layé, S., Combe, C., and Dantzer, R. (1996). Adrenalectomy enhances pro-inflammatory cytokines gene expression, in the spleen, pituitary and brain of mice in response to lipopolysaccharide. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 36, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(95)00242-K

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Griffith, R., and Sutin, J. (1996). Reactive astrocyte formation in vivo is regulated by noradrenergic axons. J. Comp. Neurol. 371, 362–375.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Griñan-Ferré, C., Pérez-Cáceres, D., Gutiérrez-Zetina, S. M., Camins, A., Palomera-Avalos, V., Ortuño-Sahagún, D., et al. (2015). Environmental enrichment improves behavior, cognition, and brain functional markers in young senescence-accelerated prone mice (SAMP8). Mol. Neurobiol. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9210-6. [Epub ahead of print].

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gubba, E. M., Fawcett, J. W., and Herbert, J. (2004). The effects of corticosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone on neurotrophic factor mRNA expression in primary hippocampal and astrocyte cultures. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 127, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guidotti, G., Calabrese, F., Anacker, C., Racagni, G., Pariante, C. M., and Riva, M. A. (2013). Glucocorticoid receptor and FKBP5 expression is altered following exposure to chronic stress: modulation by antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 616–627. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.225

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gyoneva, S., and Traynelis, S. F. (2013). Norepinephrine modulates the motility of resting and activated microglia via different adrenergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 15291–15302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458901

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hartmann, J., Wagner, K. V., Liebl, C., Scharf, S. H., Wang, X. D., Wolf, M., et al. (2012). The involvement of FK506-binding protein 51 (FKBP5) in the behavioral and neuroendocrine effects of chronic social defeat stress. Neuropharmacology 62, 332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.041

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hashikawa, N., Ogawa, T., Sakamoto, Y., Ogawa, M., Matsuo, Y., Zamami, Y., et al. (2015). Time course of behavioral alteration and mRNA levels of neurotrophic factor following stress exposure in mouse. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 35, 807–817. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0174-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hassanpoor, H., Fallah, A., and Raza, M. (2014). Mechanisms of hippocampal astrocytes mediation of spatial memory and theta rhythm by gliotransmitters and growth factors. Cell Biol. Int. 38, 1355–1366. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10326

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hatfield, T., and McGaugh, J. L. (1999). Norepinephrine infused into the basolateral amygdala posttraining enhances retention in a spatial water maze task. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 71, 232–239. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3875

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heisler, J. M., and O'Connor, J. C. (2015). Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-dependent neurotoxic kynurenine metabolism mediates inflammation-induced deficit in recognition memory. Brain Behav. Immun. 50, 115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.022

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heneka, M. T., Carson, M. J., El Khoury, J., Landreth, G. E., Brosseron, F., Feinstein, D. L., et al. (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 14, 388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heneka, M. T., Nadrigny, F., Regen, T., Martinez-Hernandez, A., Dumitrescu-Ozimek, L., Terwel, D., et al. (2010). Locus ceruleus controls Alzheimer's disease pathology by modulating microglial functions through norepinephrine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 6058–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909586107

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herman, J. P., Patel, P. D., Akil, H., and Watson, S. J. (1989). Localization and regulation of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptor messenger RNAs in the hippocampal formation of the rat. Mol. Endocrinol. 3, 1886–1894. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-11-1886

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hertz, L., Lovatt, D., Goldman, S. A., and Nedergaard, M. (2010). Adrenoceptors in brain: cellular gene expression and effects on astrocytic metabolism and [Ca(2+)]i. Neurochem. Int. 57, 411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.03.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hertz, L., Peng, L., and Dienel, G. A. (2007). Energy metabolism in astrocytes: high rate of oxidative metabolism and spatiotemporal dependence on glycolysis/glycogenolysis. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 219–249. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600343

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hertz, L., Schousboe, I., and Schousboe, A. (1984). Receptor expression in primary cultures of neurons or astrocytes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 8, 521–527. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(84)90010-1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hetier, E., Ayala, J., Bousseau, A., and Prochiantz, A. (1991). Modulation of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor expression by beta-adrenergic agonists in mouse ameboid microglial cells. Exp. Brain Res. 86, 407–413. doi: 10.1007/BF00228965

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hsu, T. M., Konanur, V. R., Taing, L., Usui, R., Kayser, B. D., Goran, M. I., et al. (2015). Effects of sucrose and high fructose corn syrup consumption on spatial memory function and hippocampal neuroinflammation in adolescent rats. Hippocampus 25, 227–239. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22368

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, R., and Hertz, L. (1995). Noradrenaline-induced stimulation of glutamine metabolism in primary cultures of astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 41, 677–683. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410514

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hutchinson, D. S., Summers, R. J., and Gibbs, M. E. (2007). Beta2- and beta3-adrenoceptors activate glucose uptake in chick astrocytes by distinct mechanisms: a mechanism for memory enhancement? J. Neurochem. 103, 997–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04789.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hutchinson, D. S., Summers, R. J., and Gibbs, M. E. (2008). Energy metabolism and memory processing: role of glucose transport and glycogen in responses to adrenoceptor activation in the chicken. Brain Res. Bull. 76, 224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.02.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hwang, I. K., Choi, J. H., Nam, S. M., Park, O. K., Yoo, D. Y., Kim, W., et al. (2014). Activation of microglia and induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus of type 2 diabetic rats. Neurol. Res. 36, 824–832. doi: 10.1179/1743132814Y.0000000330

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ilschner, S., Nolte, C., and Kettenmann, H. (1996). Complement factor C5a and epidermal growth factor trigger the activation of outward potassium currents in cultured murine microglia. Neuroscience 73, 1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00107-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jauregui-Huerta, F., Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo, Y., Gonzalez-Castañeda, R., Garcia-Estrada, J., Gonzalez-Perez, O., and Luquin, S. (2010). Responses of glial cells to stress and glucocorticoids. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 6, 195–204. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823790

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jo, W. K., Zhang, Y., Emrich, H. M., and Dietrich, D. E. (2015). Glia in the cytokine-mediated onset of depression: fine tuning the immune response. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:268. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00268

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Joëls, M., Karst, H., Alfarez, D., Heine, V. M., Qin, Y., van Riel, E., et al. (2004). Effects of chronic stress on structure and cell function in rat hippocampus and hypothalamus. Stress 7, 221–231. doi: 10.1080/10253890500070005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jones, M. E., Lebonville, C. L., Barrus, D., and Lysle, D. T. (2015). The role of brain interleukin-1 in stress-enhanced fear learning. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 1289–1296. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.317

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kabitzke, P. A., Silva, L., and Wiedenmayer, C. (2011). Norepinephrine mediates contextual fear learning and hippocampal pCREB in juvenile rats exposed to predator odor. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 96, 166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.04.003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kälin, S., Heppner, F. L., Bechmann, I., Prinz, M., Tschöp, M. H., and Yi, C. X. (2015). Hypothalamic innate immune reaction in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 339–351. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.48

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kang, K., Lee, S. W., Han, J. E., Choi, J. W., and Song, M. R. (2014a). The complex morphology of reactive astrocytes controlled by fibroblast growth factor signaling. Glia 62, 1328–1344. doi: 10.1002/glia.22684

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kang, W., Balordi, F., Su, N., Chen, L., Fishell, G., and Hébert, J. M. (2014b). Astrocyte activation is suppressed in both normal and injured brain by FGF signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, E2987–E2995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320401111

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Karatsoreos, I. N., Bhagat, S. M., Bowles, N. P., Weil, Z. M., Pfaff, D. W., and McEwen, B. S. (2010). Endocrine and physiological changes in response to chronic corticosterone: a potential model of the metabolic syndrome in mouse. Endocrinology 151, 2117–2127. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1436

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kirby, E. D., Muroy, S. E., Sun, W. G., Covarrubias, D., Leong, M. J., Barchas, L. A., et al. (2013). Acute stress enhances adult rat hippocampal neurogenesis and activation of newborn neurons via secreted astrocytic FGF2. Elife 2:e00362. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00362

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kirschbaum, C., Wolf, O. T., May, M., Wippich, W., and Hellhammer, D. H. (1996). Stress- and treatment-induced elevations of cortisol levels associated with impaired declarative memory in healthy adults. Life Sci. 58, 1475–1483. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00118-X

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Klengel, T., Mehta, D., Anacker, C., Rex-Haffner, M., Pruessner, J. C., Pariante, C. M., et al. (2013). Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 33–41. doi: 10.1038/nn.3275

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Koyama, Y. (2015). Functional alterations of astrocytes in mental disorders: pharmacological significance as a drug target. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:261. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00261

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kreisel, T., Frank, M. G., Licht, T., Reshef, R., Ben-Menachem-Zidon, O., Baratta, M. V., et al. (2014). Dynamic microglial alterations underlie stress-induced depressive-like behavior and suppressed neurogenesis. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 699–709. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.155

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kröll, S., El-Gindi, J., Thanabalasundaram, G., Panpumthong, P., Schrot, S., Hartmann, C., et al. (2009). Control of the blood-brain barrier by glucocorticoids and the cells of the neurovascular unit. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1165, 228–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04040.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

LaLumiere, R. T., Buen, T. V., and McGaugh, J. L. (2003). Post-training intra-basolateral amygdala infusions of norepinephrine enhance consolidation of memory for contextual fear conditioning. J. Neurosci. 23, 6754–6758.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Lalumiere, R. T., and McGaugh, J. L. (2005). Memory enhancement induced by post-training intrabasolateral amygdala infusions of beta-adrenergic or muscarinic agonists requires activation of dopamine receptors: involvement of right, but not left, basolateral amygdala. Learn. Mem. 12, 527–532. doi: 10.1101/lm.97405

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lambert, K. G., Gerecke, K. M., Quadros, P. S., Doudera, E., Jasnow, A. M., and Kinsley, C. H. (2000). Activity-stress increases density of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes in the rat hippocampus. Stress 3, 275–284. doi: 10.3109/10253890009001133

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lang, F., Strutz-Seebohm, N., Seebohm, G., and Lang, U. E. (2010). Significance of SGK1 in the regulation of neuronal function. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 588, 3349–3354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190926

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Laping, N. J., Nichols, N. R., Day, J. R., Johnson, S. A., and Finch, C. E. (1994). Transcriptional control of glial fibrillary acidic protein and glutamine synthetase in vivo shows opposite responses to corticosterone in the hippocampus. Endocrinology 135, 1928–1933.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Lee, C. T., Ma, Y. L., and Lee, E. H. (2007). Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase1 enhances contextual fear memory formation through down-regulation of the expression of Hes5. J. Neurochem. 100, 1531–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04284.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, M., McGeer, E., and McGeer, P. L. (2015). Activated human microglia stimulate neuroblastoma cells to upregulate production of beta amyloid protein and tau: implications for Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.024

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Legido, A., and Katsetos, C. D. (2014). Experimental studies in epilepsy: immunologic and inflammatory mechanisms. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 21, 197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2014.10.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lehmann, M. L., Brachman, R. A., Martinowich, K., Schloesser, R. J., and Herkenham, M. (2013). Glucocorticoids orchestrate divergent effects on mood through adult neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 33, 2961–2972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3878-12.2013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Levy-Gigi, E., Szabó, C., Kelemen, O., and Kéri, S. (2013). Association among clinical response, hippocampal volume, and FKBP5 gene expression in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder receiving cognitive behavioral therapy. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.017

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, S., Wang, C., Wang, W., Dong, H., Hou, P., and Tang, Y. (2008). Chronic mild stress impairs cognition in mice: from brain homeostasis to behavior. Life Sci. 82, 934–942. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.02.010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liang, K. C., Juler, R. G., and McGaugh, J. L. (1986). Modulating effects of posttraining epinephrine on memory: involvement of the amygdala noradrenergic system. Brain Res. 368, 125–133. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91049-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liang, K. C., and McGaugh, J. L. (1983). Lesions of the stria terminalis attenuate the enhancing effect of post-training epinephrine on retention of an inhibitory avoidance response. Behav. Brain Res. 9, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(83)90013-X

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liang, K. C., McGaugh, J. L., and Yao, H. Y. (1990). Involvement of amygdala pathways in the influence of post-training intra-amygdala norepinephrine and peripheral epinephrine on memory storage. Brain Res. 508, 225–233. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90400-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liberzon, I., López, J. F., Flagel, S. B., Vázquez, D. M., and Young, E. A. (1999). Differential regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors mRNA and fast feedback: relevance to post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Neuroendocrinol. 11, 11–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00288.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Longden, T. A., Dabertrand, F., Hill-Eubanks, D. C., Hammack, S. E., and Nelson, M. T. (2014). Stress-induced glucocorticoid signaling remodels neurovascular coupling through impairment of cerebrovascular inwardly rectifying K+ channel function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 7462–7467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401811111

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lupien, S. J., Wilkinson, C. W., Brière, S., Ménard, C., Ng Ying Kin, N. M., and Nair, N. P. (2002a). The modulatory effects of corticosteroids on cognition: studies in young human populations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 27, 401–416. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00061-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lupien, S. J., Wilkinson, C. W., Brière, S., Ng Ying Kin, N. M., Meaney, M. J., and Nair, N. P. (2002b). Acute modulation of aged human memory by pharmacological manipulation of glucocorticoids. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 3798–3807. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8760

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mann, S. A., Versmold, B., Marx, R., Stahlhofen, S., Dietzel, I. D., Heumann, R., et al. (2008). Corticosteroids reverse cytokine-induced block of survival and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells from rats. J. Neuroinflammation 5:39. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-39

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Martocchia, A., Stefanelli, M., Falaschi, G. M., Toussan, L., Ferri, C., and Falaschi, P. (2015). Recent advances in the role of cortisol and metabolic syndrome in age-related degenerative diseases. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0353-0. [Epub ahead of print].

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McNay, E. C., and Gold, P. E. (2002). Food for thought: fluctuations in brain extracellular glucose provide insight into the mechanisms of memory modulation. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 1, 264–280. doi: 10.1177/1534582302238337

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Melcangi, R. C., Cavarretta, I., Magnaghi, V., Ciusani, E., and Salmaggi, A. (2000). Corticosteroids protect oligodendrocytes from cytokine-induced cell death. Neuroreport 11, 3969–3972. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200012180-00013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Miura, H., Ozaki, N., Sawada, M., Isobe, K., Ohta, T., and Nagatsu, T. (2008). A link between stress and depression: shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression. Stress 11, 198–209. doi: 10.1080/10253890701754068

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Miyata, S., Hattori, T., Shimizu, S., Ito, A., and Tohyama, M. (2015). Disturbance of oligodendrocyte function plays a key role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:492367. doi: 10.1155/2015/492367

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Miyata, S., Koyama, Y., Takemoto, K., Yoshikawa, K., Ishikawa, T., Taniguchi, M., et al. (2011). Plasma corticosterone activates SGK1 and induces morphological changes in oligodendrocytes in corpus callosum. PLoS ONE 6:e19859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019859

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mocchetti, I., Spiga, G., Hayes, V. Y., Isackson, P. J., and Colangelo, A. (1996). Glucocorticoids differentially increase nerve growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor expression in the rat brain. J. Neurosci. 16, 2141–2148.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Molteni, R., Fumagalli, F., Magnaghi, V., Roceri, M., Gennarelli, M., Racagni, G., et al. (2001). Modulation of fibroblast growth factor-2 by stress and corticosteroids: from developmental events to adult brain plasticity. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 37, 249–258. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00128-X

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Moraga-Amaro, R., Jerez-Baraona, J. M., Simon, F., and Stehberg, J. (2014). Role of astrocytes in memory and psychiatric disorders. J. Physiol. Paris 108, 240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2014.08.005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mori, K., Ozaki, E., Zhang, B., Yang, L., Yokoyama, A., Takeda, I., et al. (2002). Effects of norepinephrine on rat cultured microglial cells that express alpha1, alpha2, beta1 and beta2 adrenergic receptors. Neuropharmacology 43, 1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00211-3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Morris, G. P., Clark, I. A., Zinn, R., and Vissel, B. (2013). Microglia: a new frontier for synaptic plasticity, learning and memory, and neurodegenerative disease research. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 105, 40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.07.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mufson, E. J., Ginsberg, S. D., Ikonomovic, M. D., and DeKosky, S. T. (2003). Human cholinergic basal forebrain: chemoanatomy and neurologic dysfunction. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 26, 233–242. doi: 10.1016/S0891-0618(03)00068-1

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Munhoz, C. D., Lepsch, L. B., Kawamoto, E. M., Malta, M. B., Lima Lde, S., Avellar, M. C., et al. (2006). Chronic unpredictable stress exacerbates lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in the frontal cortex and hippocampus via glucocorticoid secretion. J. Neurosci. 26, 3813–3820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4398-05.2006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nelson, P. A., Sage, J. R., Wood, S. C., Davenport, C. M., Anagnostaras, S. G., and Boulanger, L. M. (2013). MHC class I immune proteins are critical for hippocampus-dependent memory and gate NMDAR-dependent hippocampal long-term depression. Learn. Mem. 20, 505–517. doi: 10.1101/lm.031351.113

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

Nichols, N. R., Masters, J. N., and Finch, C. E. (1990). Changes in gene expression in hippocampus in response to glucocorticoids and stress. Brain Res. Bull. 24, 659–662. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90004-J

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nisticò, R., Mori, F., Feligioni, M., Nicoletti, F., and Centonze, D. (2014). Synaptic plasticity in multiple sclerosis and in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369:20130162. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0162

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Notarianni, E. (2013). Hypercortisolemia and glucocorticoid receptor-signaling insufficiency in Alzheimer's disease initiation and development. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 10, 714–731. doi: 10.2174/15672050113109990137

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

O'Donnell, J., Zeppenfeld, D., McConnell, E., Pena, S., and Nedergaard, M. (2012). Norepinephrine: a neuromodulator that boosts the function of multiple cell types to optimize CNS performance. Neurochem. Res. 37, 2496–2512. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0818-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Oitzl, M. S., and de Kloet, E. R. (1992). Selective corticosteroid antagonists modulate specific aspects of spatial orientation learning. Behav. Neurosci. 106, 62–71. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.106.1.62

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Oitzl, M. S., Reichardt, H. M., Joëls, M., and de Kloet, E. R. (2001). Point mutation in the mouse glucocorticoid receptor preventing DNA binding impairs spatial memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12790–12795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231313998

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Osborne, D. M., Pearson-Leary, J., and McNay, E. C. (2015). The neuroenergetics of stress hormones in the hippocampus and implications for memory. Front. Neurosci. 9:164. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00164

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

Parpura, V., Grubišic, V., and Verkhratsky, A. (2011). Ca(2+) sources for the exocytotic release of glutamate from astrocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pascual, O., Ben Achour, S., Rostaing, P., Triller, A., and Bessis, A. (2012). Microglia activation triggers astrocyte-mediated modulation of excitatory neurotransmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E197–E205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111098109

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Patterson, S. L. (2015). Immune dysregulation and cognitive vulnerability in the aging brain: interactions of microglia, IL-1beta, BDNF and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 96, 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.020

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Petrov, T., Krukoff, T. L., and Jhamandas, J. H. (1993). Branching projections of catecholaminergic brainstem neurons to the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus and the central nucleus of the amygdala in the rat. Brain Res. 609, 81–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90858-K

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Polman, J. A., de Kloet, E. R., and Datson, N. A. (2013). Two populations of glucocorticoid receptor-binding sites in the male rat hippocampal genome. Endocrinology 154, 1832–1844. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2187

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Popoli, M., Yan, Z., McEwen, B. S., and Sanacora, G. (2012). The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 22–37. doi: 10.1038/nrn3138

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Psarra, A. M., and Sekeris, C. E. (2009). Glucocorticoid receptors and other nuclear transcription factors in mitochondria and possible functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.11.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Quirarte, G. L., Roozendaal, B., and McGaugh, J. L. (1997). Glucocorticoid enhancement of memory storage involves noradrenergic activation in the basolateral amygdala. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 14048–14053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14048

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Radley, J. J., Anderson, R. M., Hamilton, B. A., Alcock, J. A., and Romig-Martin, S. A. (2013). Chronic stress-induced alterations of dendritic spine subtypes predict functional decrements in an hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal-inhibitory prefrontal circuit. J. Neurosci. 33, 14379–14391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0287-13.2013

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ramos-Rodriguez, J. J., Jimenez-Palomares, M., Murillo-Carretero, M. I., Infante-Garcia, C., Berrocoso, E., Hernandez-Pacho, F., et al. (2015). Central vascular disease and exacerbated pathology in a mixed model of type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. Psychoneuroendocrinology 62, 69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.606

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reul, J. M., and de Kloet, E. R. (1985). Two receptor systems for corticosterone in rat brain: microdistribution and differential occupation. Endocrinology 117, 2505–2511. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2505

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reul, J. M., and de Kloet, E. R. (1986). Anatomical resolution of two types of corticosterone receptor sites in rat brain with in vitro autoradiography and computerized image analysis. J. Steroid Biochem. 24, 269–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90063-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reul, J. M., Bilang-Bleuel, A., Droste, S., Linthorst, A. C., Holsboer, F., and Gesing, A. (2000a). New mode of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis regulation: significance for stress-related disorders. Z Rheumatol 59(Suppl. 2), II/22–25.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Reul, J. M., Gesing, A., Droste, S., Stec, I. S., Weber, A., Bachmann, C., et al. (2000b). The brain mineralocorticoid receptor: greedy for ligand, mysterious in function. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 405, 235–249. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00677-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rodríguez, J. J., Witton, J., Olabarria, M., Noristani, H. N., and Verkhratsky, A. (2010). Increase in the density of resting microglia precedes neuritic plaque formation and microglial activation in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Dis. 1, e1. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2009.2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roozendaal, B. (2002). Stress and memory: opposing effects of glucocorticoids on memory consolidation and memory retrieval. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 78, 578–595. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4080

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roozendaal, B. (2003). Systems mediating acute glucocorticoid effects on memory consolidation and retrieval. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 27, 1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.015

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roozendaal, B., Carmi, O., and McGaugh, J. L. (1996). Adrenocortical suppression blocks the memory-enhancing effects of amphetamine and epinephrine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 1429–1433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1429

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roozendaal, B., and McGaugh, J. L. (1996). Amygdaloid nuclei lesions differentially affect glucocorticoid-induced memory enhancement in an inhibitory avoidance task. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 65, 1–8. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roozendaal, B., Nguyen, B. T., Power, A. E., and McGaugh, J. L. (1999). Basolateral amygdala noradrenergic influence enables enhancement of memory consolidation induced by hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11642–11647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11642

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ross, F. M., Allan, S. M., Rothwell, N. J., and Verkhratsky, A. (2003). A dual role for interleukin-1 in LTP in mouse hippocampal slices. J. Neuroimmunol. 144, 61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.08.030

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sahlender, D. A., Savtchouk, I., and Volterra, A. (2014). What do we know about gliotransmitter release from astrocytes? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369:20130592. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0592

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sandi, C., Loscertales, M., and Guaza, C. (1997). Experience-dependent facilitating effect of corticosterone on spatial memory formation in the water maze. Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 637–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01412.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sandi, C., and Rose, S. P. (1994a). Corticosteroid receptor antagonists are amnestic for passive avoidance learning in day-old chicks. Eur. J. Neurosci. 6, 1292–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00319.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sandi, C., and Rose, S. P. (1994b). Corticosterone enhances long-term retention in one-day-old chicks trained in a weak passive avoidance learning paradigm. Brain Res. 647, 106–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91404-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sandi, C., and Rose, S. P. (1997). Training-dependent biphasic effects of corticosterone in memory formation for a passive avoidance task in chicks. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 133, 152–160. doi: 10.1007/s002130050385

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sapolsky, R. M., Krey, L. C., and McEwen, B. S. (1985). Prolonged glucocorticoid exposure reduces hippocampal neuron number: implications for aging. J. Neurosci. 5, 1222–1227.