Frontiers | Is acceptance and commitment therapy helpful in reducing anxiety symptomatology in people aged 65 or over? A systematic review (original) (raw)

Introduction

Anxiety-related mental health problems in older adults are among the most persistent, prevalent and impactful (1–3). However, even today, their prevalence is not yet established. Values for anxiety-related mental health problems range from 1.20 to 15%, while rates of clinically significant anxiety symptoms vary from 15 to 52% (4). It has been found that anxiety disorders tend to be persistent in older adults, with an average duration of 20 years or more (5). Furthermore, there appears to be a bidirectional association between anxiety and disability (2, 6): anxiety increases disability and worsens both quality of life and life satisfaction (4) and is associated with an increased risk of mortality in older adults, both from suicide and physical illness (7). Besides, anxiety is considered a risk factor for cognitive impairment in cognitively normal older adults (8). In fact, there is evidence that suggests that anxiety in older adults may lead to mild cognitive amnestic impairment (8). Despite the above, few studies have focused on developing psychological treatments adapted to older people (9).

The tendency toward fear and avoidance of internal experiences is a relevant feature of people with anxiety (10). Experiential avoidance is defined by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) as one of the psychological inflexibility processes associated with psychopathology (11). According to Hayes, et al. (11), the six processes associated with psychological inflexibility and consequently psychopathology are experiential avoidance, cognitive defusion, dominance of the conceptualized past or future, disengagement from personal values, impulsivity, and persistent avoidance. Research suggests that these core psychopathology processes persist into adulthood, with a significant association between experiential avoidance of distressing internal experiences and increased anxiety in later life (12). People who display psychological inflexibility are considered to exert energy and resources toward experiential avoidance, as well as neglecting and disengaging from core values in their lives (12). Kashdan, et al. (13) used a 21-day experience sampling methodology to examine the relationships between experiential avoidance, suppressing emotions, and cognitive reappraisal with daily reports of social anxiety. Including cognitive reappraisal allowed the comparison of a core process of traditional cognitive-behavioral therapies with the core process of acceptance and attention-based therapies, experiential avoidance or acceptance. The results showed that people who worked with ACT intervention techniques reported a significant reduction in anxiety levels. ACT-based treatment aims to focus attention on feeling better and living better. These authors consider ACT-based exercises to be more effective than cognitive behavioral therapy as they are not portrayed as a way to reduce anxiety, but as a strategy to develop a willingness to deal with anxiety while progressing toward a set of desired goals (13). Similar studies have shown how thought suppression as a mechanism to combat unwanted thoughts has been associated with a less subjective meaning of one's life in older adults (14). Petkus & Wetherell, et al. (12) confirmed how thought suppression was associated with more somatic, depressive and anxiety symptoms after physical, functional and cognitive disease control in a sample of older adults with functional disability and chronic illness (12). In the same line, more recent research exploring ACT in older adults suggests that ACT contributes more significantly to alleviating anxious symptoms than traditional cognitive-behavioral techniques (2, 15, 16).

Numerous reasons support the appropriateness of ACT in older adults (9, 10, 17). On the one hand, anxiety disorders often present a chronic condition resulting in their onset prior to old age and their persistence over time (5). In addition, anxiety disorders often show greater resistance to treatment in older adults (9). On the other hand, comorbidity of anxiety and depression are common in older adults, making them more difficult to differentiate (18). The transdiagnostic nature of ACT makes assessment and intervention for anxiety and depression more efficient, as it is not necessary to distinguish between both pathologies, as it focuses exclusively on determining how core processes of psychological inflexibility contribute to psychopathology in order to intervene on them, regardless of the current mental health problem (12). In addition, ACT can be beneficial in cases where psychological distress is associated with loss-related factors that are unavoidable and immutable. In this way, the acceptance approach and refocusing behaviors on attainable goals aligned with one's values can be particularly beneficial (17).

In summary, the particularities and challenges presented by anxiety in older adults require special attention to address this issue in an idiosyncratic manner. ACT has shown to be potentially successful in this regard; however, more evidence is needed to support these findings so far, especially in older adults. Therefore, this study aimed to conduct a systematic review in order to compile the available evidence on the efficacy of ACT in older adults with anxiety problems.

Methods

This systematic review was developed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (19).

Bibliographic search

The Proquest, Pubmed, Web of Science and Scopus databases were consulted by two authors (LL-T and JM-M), exploring articles published before 29th May 2022. Using the PICO approach (20), the following research question was posed: do older people who undergo ACT improve their anxiety levels?.

The searching protocol was applied to all the selected databases and was constructed as follows: “acceptance and commitment therapy” AND (anxiety OR “anxiety disorders”) AND (aged OR aging). In order to optimize the process, standardized terms were retrieved from the Medical Subject Headings—MeSH (English) and from Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud—DeCS (Spanish).

All selected articles were managed through the Covidence software. First, duplicate articles were eliminated, after which the two authors (LL-T and JM-M) reviewed the manuscripts with emphasis on the title and abstract, determining compliance with the eligibility criteria separately. In this process, articles were screened independently and in a blind manner with regard to the other author's decision. If there were conflicts, a second in-depth reading was performed individually. Finally, disagreements were resolved through active discussion. A third reviewer (IDL) provided arbitration in cases where consensus could not be reached.

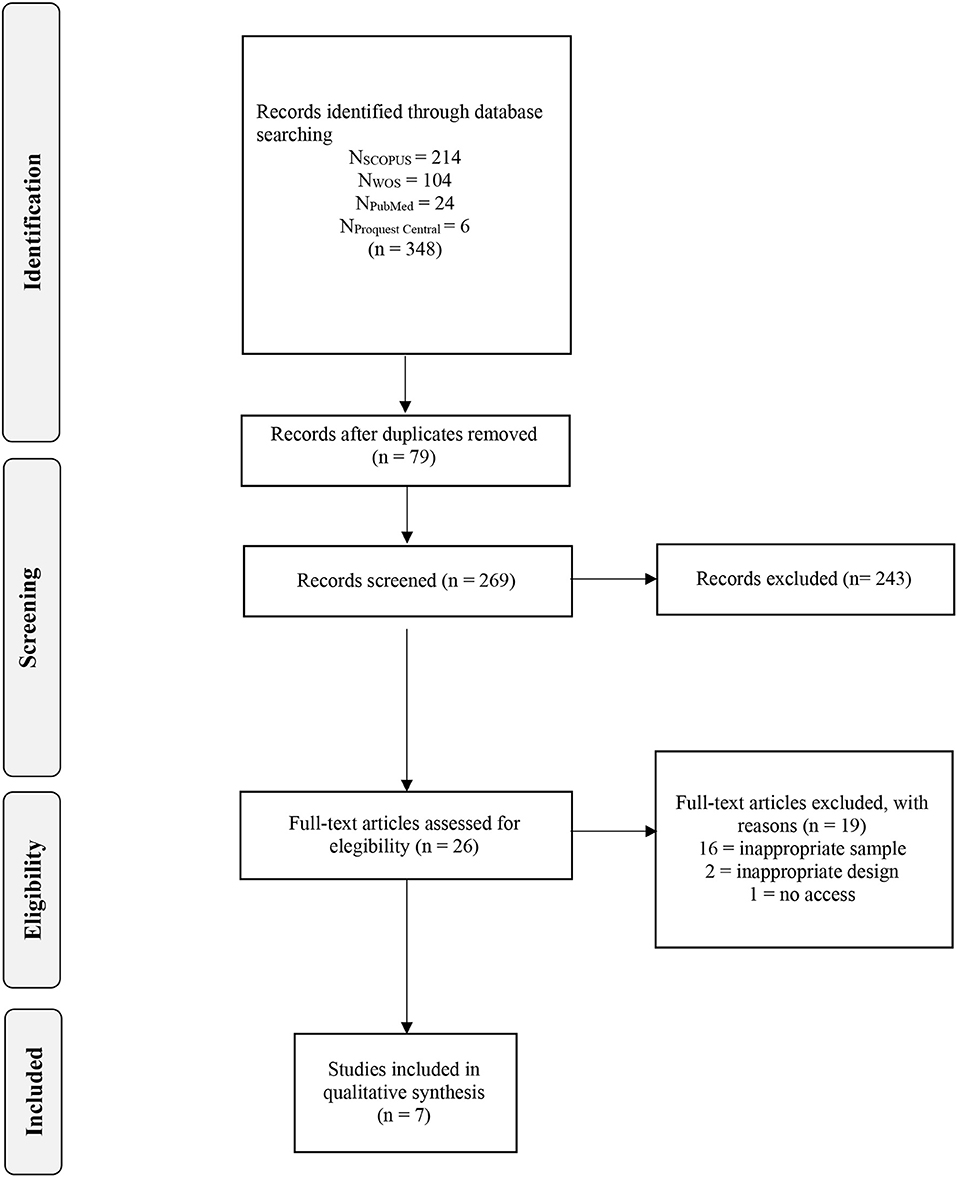

The Cohen's Kappa index (κ) (21) was used to evaluate the agreement between judges; values between−1 and.40 are considered unsatisfactory, those between 0.41 and 0.75 are considered acceptable, and those that score 0.76 or higher are considered satisfactory (22). Figure 1 displays the flowchart that depicts the selection process.

Figure 1. Flowchart of selection process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (a) the study assessed the benefits attributable ACT on the anxious symptomatology, (b) the age of the sample was 65 years or older, (c) the manuscript underwent a peer review process, (d) the article was published in a journal with significant impact factor, (e) the study was published in English or Spanish, and (f) the paper was published within the last 10 years.

The following exclusion criteria were agreed upon: (a) samples of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, (b) samples of patients diagnosed with severe medical conditions, (c) publications derived from conferences, (d) studies based on a narrative review, and (e) studies that did not explore anxiety using a scientifically validated questionnaire.

Data collection

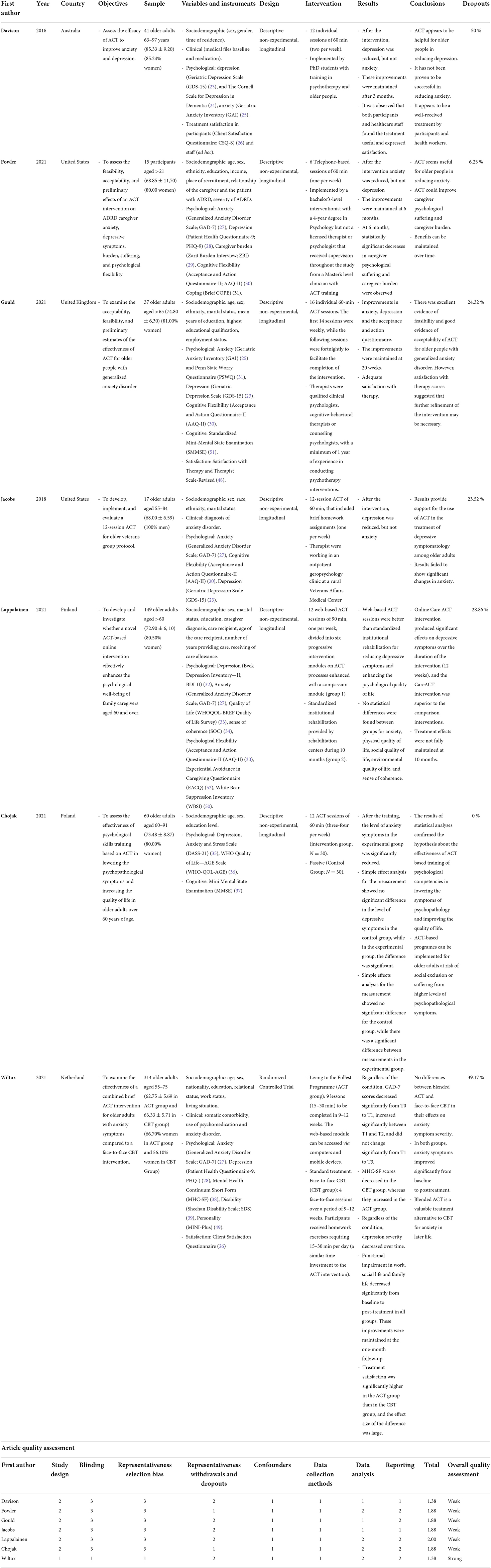

One of the authors (LLT) developed an ad hoc table to synthesize all relevant information from the selected articles. This information included: (a) first author, (b) year of publication, (c) source country, (d) objectives, (e) sample, (f) variables and instruments, (g) design, (h) intervention, (i) results, (j) main conclusions, (k) methodological rigor indices, and (l) dropouts (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review (N = 7) and article quality assessment.

Quality assessment

Two authors (LL-T and JM-M) assessed the methodological rigor of the selected studies in an independent and blinded manner using an adapted version of the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (40). This tool consists of 19 items that assess 8 criteria: (a) study design, (b) blinding, (c) selection bias, (d) withdrawals and dropouts, (e) confounders, (f) data collection methods, (g) data analysis, and (h) reporting. Studies can have between 4 and 8 component ratings based on these criteria (41). The average quality score was 1.84, with quality scores ranging from 1 to 3, with 1 being the highest score (least likely to be biased and highest quality) and 3 being the weakest score (most likely to be biased or lowest quality). A study with 6 ratings could be rated as “strong” if there are no weak ratings and at least 3 strong ratings, “moderate” if there is one rating and <3 strong ratings, or “weak” if there are two or more weak ratings.

Results

Study selection and screening

The study selection process is shown in Figure 1. The literature screening resulted in a total of 348 records. After removing duplicates, the total number of records was 77. The initial selection excluded 189 studies based on title and abstract, and the full content of the remaining 42 papers was read as part of a second selection process. The reliability of prior agreement between the two independent reviewers (LL-T and JM-M) in the full-text selection was excellent (κ = 0.84). In the second screening, 30 papers were excluded resulting in 7 dependent studies being eligible for inclusion. The degree of agreement between the reviewers was also excellent (κ = 0.82).

Characteristics of the study

The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1. The seven studies investigated included a total of 633 older adults. The samples ranged from 15 participants to 134, with an average sample size of 90.43. Of the participants, 68.94% were female. The age of participants ranged from 57.14 to 94.22 years, with an average of 68.89 years. All studies were longitudinal. However, only two of them included a control group; one had the same control group as the experimental group (waiting list), and in the other, the control group received CBT. Three of the studies had at least one follow-up. The mean assessment time in these studies was 6.86 weeks for the first measurement, ranging from 6 to 24 months between assessments. The mean number of weeks at follow-up was 24.60.

Regarding the sample's representativeness for treatment dropout, all but one study reported this information. This percentage ranged from 6.25 to 39.17. The mean dropout rate from the studies was estimated at 24.66%. Futhermore, although most papers do not mention the reason, they are generally high. In those that do mention the reason for dropout, it is said to be due to difficulties in following treatment or death. There was considerable heterogeneity in the independent and dependent variables assessed (χ2 = 8.55, p = 0.010, V = 0.45) as well as in the number of participants (χ2 = 10.00, p = 0.007, V = 0.60). However, the study designs were acceptably heterogeneous (χ2 = 0,09, p = ,520, V = 0,01). Most studies assessed anxiety, depression, stress or burden, and ACT elements such as cognitive flexibility. Other variables of interest were personality, psychopathology, life satisfaction, cognitive impairment and quality of life. Four studies report that the therapy was conducted by qualified psychologists, while the rest do not provide any information. Most interventions lasted for about 12 weeks, but in one case (42), treatment lasted for 6 sessions, and in another (15), it lasted for 16 sessions. There was also heterogeneity in the presentation of the therapies. Overall, 4 studies were individual and face-to-face, while one study (42) was conducted over the telephone and two studies were conducted over online modules. In this regard, the two reviewers (LL-T and JM-M) assessed the presence or absence of a control group and the presentation format, with inter-rater reliability reaching an almost perfect level of agreement (κ = 90). Every study controlled at least one confounding variable (medication intake, type of medication, caregiver relationship, gender, background, session attendance, waiting time between treatment and assessment, marital status, education, employment status, mental health status, and socio-demographic and clinical variables), and they all mention inclusion and exclusion criteria. In general, weak statistical tests were used. However, two studies (15, 43) did use ANCOVA to evaluate the programmes.

Discussion

This study aimed to conduct a systematic review to compile the available evidence on the efficacy of ACT in older adults with anxiety problems. A total of 7 papers were included. Overall, 57.14% of the studies focused on the population with generalized anxiety disorder, 28.57% on caregivers of dependent persons and 14.29% on anxious and depressive symptoms associated with long-term institutionalization.

These studies showed how ACT was effective in reducing depressive (15, 43–47), and anxiety symptoms (15, 42, 44, 47). Regarding anxiety, the results are less consistent, with studies concluding that ACT could reduce anxiety symptoms (15, 42, 44, 47) and other studies finding that it does not (43, 45, 46). One of the studies (47) compared the benefits of ACT with those of traditional CBT, concluding that both procedures effectively reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, ACT showed a superior therapeutic impact on mental health and treatment satisfaction. For both ACT and CBT, the effects were maintained at follow-up. Another paper (46) compared ACT treatment conducted online with the traditional approach provided by rehabilitation centers, finding that the online modality of ACT was more effective in reducing depressive symptoms and strengthening the psychological components of quality of life.

The findings of the reviewed studies have some limitations. Some of the studies have been conducted with very small samples (42, 45). Furthermore, there is a lack of control and experimental groups (15, 42, 43, 45, 46), and only one randomized controlled trial was found (47). On the other hand, the available studies assess anxiety in various ways, in many cases alongside other emotional problems. In 25% of the studies, the GAI was used (25), 50% used the GAD-7 (34), 12.50% used the DASS-21 (35) and the remaining 12.50% used ad hoc semi-structured interviews. In addition to the above, most of the studies included have high drop-out rates of over 20%. Not all studies provide reasons for the dropouts. Finally, despite having performed a heterogeneity analysis, results should be considered cautiously. This type of analysis should be conducted in more endline studies.

However, preliminary results indicate that ACT can be beneficial for treating anxiety problems in older adults, particularly suitable for this population's characteristics (2, 15, 17). Therefore, these tools should be studied in greater depth to maximize their benefits. In this regard, further research of higher quality is required, including additional randomized controlled trials specifically targeting older people.

The results of this research may be affected by some biases, including the following: biases in the sample size, as well as in the research design (non-randomization of participants, general lack of control and experimental group, no double-blind allocation between control and experimental group; use of weak statistics and general lack of follow-up), assessment biases (selection of non-specific assessment instruments for older adults), and sampling biases.

On the other hand, the limited selection of articles directly related to the systematicity of the review requires further research. In addition to the above, most articles address the benefits of ACT in older people with a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, but other clinical conditions of the same psychopathological category are underrepresented. Furthermore, there has been a significant heterogeneity of assessment methods and therapeutic procedures. Although the number of sessions tends to be similar among the studies; their contents, timing and administration methods are highly variable, making it impossible to carry out a meta-analysis at the present time. Similarly, the quality of the studies analyzed has been found to be moderate or weak.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review conducted on the possible benefits of ACT on anxiety in older adults. Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that there is a need for further higher-quality research focused on this area that would allow to truly evaluate the benefits of ACT in older adults.

Author contributions

ID: project management, literature search, writing the original manuscript, and revising the manuscript. JM-M: review proposal, conducting the search process, methodology, review and synthesis of the review articles, and writing the original manuscript and revision. LL-T: review proposal, conducting the search process, review and synthesis of the review articles, and statistical analysis and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

Research Project Emotional intelligence as a resource for successful adaptation in everyday life (PII2021_06), funded by Valencian International University. LL-T is a beneficiary of the Ayuda de Atracció a Talent de la Universitat de València (0113/2018).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Valencian International University and the Universitat de València for the funding received.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Andreas S, Schulz H, Volkert J, Dehoust M, Sehner S, Suling A, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in elderly people: the European MentDis_ICF65+ study. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 125:125–31. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180463

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Lenze E, Wetherell JL. A lifespan view of anxiety disorders. Dial Clin Neurosci. (2022) 13:381–99. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/elenze

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Zilber N, Lerner Y, Eidelman R, Kertes J. Depression and anxiety disorders among Jews from the former Soviet Union five years after their immigration to Israel. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2001) 16:993–9. doi.org/10.1002/gps.456 doi: 10.1002/gps.456

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Bryant C, Jackson H, Ames D. The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: methodological issues and a review of the literature. J Affect Disord. (2008) 109:233–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Brenes GA, Kritchevsky SB, Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Simonsick EM, Ayonayon HN, et al. Scared to death: results from the health, aging, and body composition study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2007) 15:262–5. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31802e21f0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Allagulander C, Lavori PW. Causes of death among 936 elderly patients with “pure” anxiety neurosis in Stockholm County, Sweden, and patients with depressive neurosis or both diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry. (1993) 34:299–302. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(93)90014-U

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Hanseeuw BJ, Jonas V, Jackson J, Betensky RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, et al. Association of anxiety with subcortical amyloidosis in cognitively normal older adults. Mol Psychiatry. (2020) 25:2599–607. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0214-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Lawrence V, Kimona K, Howard RJ, Serfaty MA, Wetherell JL, Livingston G, et al. Optimising the acceptability and feasibility of acceptance and commitment therapy for treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder in older adults. Age Ageing. (2019) 48:741–50. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz082

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Roemer L, Salters K, Raffa SD, Orsillo SM. Fear and avoidance of internal experiences in GAD: preliminary tests of a conceptual model. Cognit Ther Res. (2005) 29:71–88. doi: 10.1007/s10608-005-1650-2

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Kashdan TB, Barrios V, Forsyth JP, Steger MF. Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:1301–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Gould RL, Wetherell JL, Kimona K, Serfaty MA, Jones R, Graham CD, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for late-life treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder: a feasibility study. Age Ageing. (2021) 50:1751–61. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab059

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Wetherell JL, Liu L, Patterson TL, Afari N, Ayers CR, Thorp SR, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: a preliminary report. Behav Ther. (2011) 42:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.07.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Roberts SL, Sedley B. Acceptance and commitment therapy with older adults: rationale and case study of an 89-year-old with depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Clin Case Stud. (2016) 15:53–67. doi: 10.1177/1534650115589754

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. (2015) 349:1–25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Santos CMC, Pimenta CAM, Nobre MRC. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. (2007) 15:508–11. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692007000300023

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Orwin RG. Evaluating coding decisions. In:Cooper H, Hedges LV, , editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation (1994). p. 139–62.

22. Hernández Nieto R. Contribuciones al analisis estadistico: sensibilidad estabilidad y consistencia de varios coeficientes de variabilidad relativa y el coeficiente de variacion proporcional cvp el coeficiente: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; (2002).

25. Pachana NA, Byrne GJ, Siddle H, Koloski N, Harley E, Arnold E. Development and validation of the geriatric anxiety inventory. Int Psychogeriatr. (2007) 19:103–14. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003504

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. The UCSF Client Satisfaction Scales: I. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers (2004). p. 799–811.

27. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther. (2011) 42:676–88. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the penn state worry questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. (1990) 28:487–95. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of beck depression inventories – IA and II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. (1996) 67:588–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell KA. The world health organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. (2004) 13:299–31. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Antonovsky A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass (1987).

35. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. (1995) 33:335–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Zawisza K, Gałaś S, Adamczyk BT. Validation of the Polish version of the WHOQOL-AGE scale in older population. Gerontologia Polska. (2016) 24:7–16.

37. Pangman V, Sloan J, Guse L. An examination of psychometric properties of the mini-mental state examination and the standardized mini-mental state examination: implications for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res. (2000) 13:209–13. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2000.9231

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Lamers SMA, Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET. ten Klooster PM, Keyes CLM. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). J Clin Psychol. (2011) 67:99–110. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20741

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the sheehan disability scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. (1997) 27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Wermelinger Ávila MP, Lucchetti ALG. Association between depression and resilience in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2017) 32:237–46. doi: 10.1002/gps.4619

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. McMullan RD, Berle D, Arnáez S, Starcevic V. The relationships between health anxiety, online health information seeking and cyberchondria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2019) 15:270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.037

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Fowler NR, Judge KS, Lucas K, Gowan T, Stutz P, Shan M, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an acceptance and commitment therapy intervention for caregivers of adults with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 1:127. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02078-0

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Davison TE, Eppingstall B, Runci S, O'Connor DW. A pilot trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety in older adults residing in long-term care facilities. Aging Ment Health. (2017) 21:766–73. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1156051

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Chojak A. Effectiveness of a training programme based on acceptance and commitment therapy aimed at older adults – no moderating role of cognitive functioning. Neuropsychiatria i Neuropsychol/Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol. (2021) 16:138–46. doi: 10.5114/nan.2021.113314

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Jacobs ML, Luci K, Hagemann L. Group-based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for older veterans: findings from a quality improvement project. Clin Gerontol. (2018) 41:458–67. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1391917

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Lappalainen P, Pakkala I, Lappalainen R, Nikander R. Supported web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for older family caregivers (CareACT) compared to usual care. Clin Gerontol. (2021) 45:939–55. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2021.1912239

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

47. Wiltox M, Garnefski N, Kraaij V, De Waal MWM, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, et al. Blended acceptance and commitment therapy versus face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy for older adults with anxiety symptoms in primary care: pragmatic single-blind cluster randomized trial. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e24366. doi: 10.2196/24366

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Oei TP, Green AL. The satisfaction with therapy and therapist scale-revised (STTS-R) for group psychotherapy: psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis. Prof Psychol Res Pr. (2008) 39:435–42. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.435

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan K. The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur J Psychiatry. (1997) 12:224–31. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

51. Molloy DW, Alemayehu E, Roberts R. Reliability of a standardized mini-mental state examination compared with the traditional mini-mental state examination. Am J Psychiatry. (1991) 148:102–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.102

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

52. Losada A, Márquez González M, Romero Moreno R, López J. Development and validation of the experiential avoidance in caregiving questionnaire (EACQ). Aging Ment Health. (2014) 18:897–904. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.896868