Current status of function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer (original) (raw)

Topic Highlight Open Access

Copyright ©2014 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved.

World J Gastroenterol. Dec 14, 2014; 20(46): 17297-17304

Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17297

Current status of function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer

Takuro Saito, Yukinori Kurokawa, Shuji Takiguchi, Masaki Mori, Yuichiro Doki, Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka 565-0871, Japan

ORCID number: $[AuthorORCIDs]

Author contributions: All authors contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data.

Correspondence to: Yukinori Kurokawa, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-2-E2, Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan. ykurokawa@gesurg.med.osaka-u.ac.jp

Telephone: +81-6-68793251 Fax: +81-6-68793259

Received: May 27, 2014

Revised: July 16, 2014

Accepted: September 5, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 204 Days and 20.1 Hours

Abstract

Recent advances in diagnostic techniques have allowed the diagnosis of gastric cancer (GC) at an early stage. Due to the low incidence of lymph node metastasis and favorable prognosis in early GC, function-preserving surgery which improves postoperative quality of life may be possible. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) is one such function-preserving procedure, which is expected to offer advantages with regards to dumping syndrome, bile reflux gastritis, and the frequency of flatus, although PPG may induce delayed gastric emptying. Proximal gastrectomy (PG) is another function-preserving procedure, which is thought to be advantageous in terms of decreased duodenogastric reflux and good food reservoir function in the remnant stomach, although the incidence of heartburn or gastric fullness associated with this procedure is high. However, these disadvantages may be overcome by the reconstruction method used. The other important problem after PG is remnant GC, which was reported to occur in approximately 5% of patients. Therefore, the reconstruction technique used with PG should facilitate postoperative endoscopic examinations for early detection and treatment of remnant gastric carcinoma. Oncologic safety seems to be assured in both procedures, if the preoperative diagnosis is accurate. Patient selection should be carefully considered. Although many retrospective studies have demonstrated the utility of function-preserving surgery, no consensus on whether to adopt function-preserving surgery as the standard of care has been reached. Further prospective randomized controlled trials are necessary to evaluate survival and postoperative quality of life associated with function-preserving surgery.

Core tip: We reviewed the current status of two function-preserving surgeries for gastric cancer (GC), pylorus-preserving surgery and proximal gastrectomy (PG). Although both procedures appear to be oncologically safe for early GC, issues regarding postoperative quality of life remain, especially with PG. The effect of the reconstruction method after PG on postoperative quality of life was analyzed, including the novel double tract reconstruction method, which is expected to overcome disadvantages associated with esophagogastrostomy and jejunal interposition reconstruction. Although some reports showed a benefit with function-preserving surgery, further randomized trials are needed.

- Citation: Saito T, Kurokawa Y, Takiguchi S, Mori M, Doki Y. Current status of function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17297-17304

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17297.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17297

INTRODUCTION

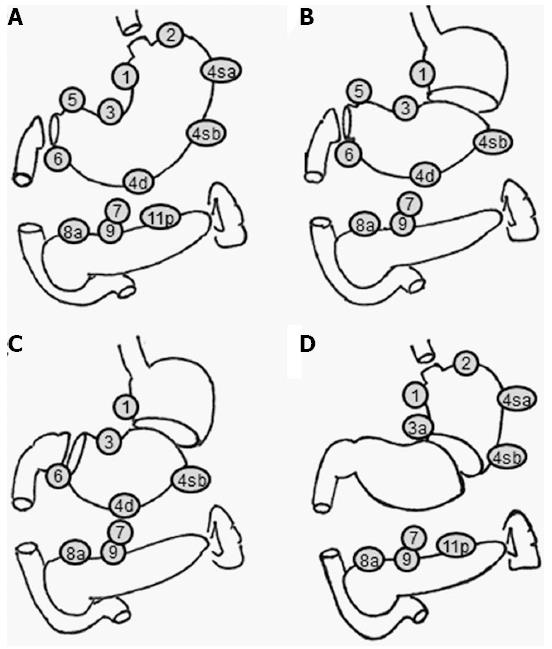

Recent developments in screening programs and endoscopic techniques have allowed the diagnosis of gastric cancer (GC) at an early stage[1]. Early GC (EGC) makes up 50% of the diagnosed cases and the five-year survival rate of EGC treated with surgery is over 90% in Japan[2]. Due to the low incidence of lymph node metastasis and the favorable prognosis of EGC, areas of gastric resection and lymph node dissection areas could be reduced to preserve postoperative gastric function. Although the Japanese GC treatment guidelines advocate resection of at least two-thirds of the stomach with D2 node dissection as the standard treatment for most stages of advanced GC, the guidelines also describe less invasive procedures such as pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG), proximal gastrectomy (PG), and other minimally invasive procedures as investigational treatments (Figure 1)[3].

Figure 1 Extent of D1+ lymph node dissection in pylorus-preserving gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy. A: Total gastrectomy; B: Distal gastrectomy; C: Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy; D: Proximal gastrectomy. The number of lymph node stations is according to the classification of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association.

Here we review PPG and PG as function-preserving procedures for GC.

PPG

PPG was initially used to treat peptic ulcers[4]. Starting in the late 1980s, some surgeons performed PPG in selected patients with EGC to improve postoperative gastric function and maintain patient quality of life[5]. PPG is generally thought to offer several advantages over conventional distal gastrectomy (DG) with Billroth I reconstruction in terms of the incidence of dumping syndrome, bile reflux gastritis, and the frequency of flatus, although the operative duration of PPG is longer than that of DG.

During the procedure, the distal part of the stomach is resected, but a pyloric cuff 2-3 cm wide is preserved[6,7]. The right gastric artery and the infrapyloric artery are preserved to maintain the blood supply to the pyloric cuff. In addition, the hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagal nerves are preserved to maintain pyloric function. The celiac branch of the posterior vagal trunk is sometimes preserved. All regional nodes except the suprapyloric nodes (No. 5) should be dissected as in the standard D2 procedure. However, there are technical challenges associated with completing all of these procedures. Shibata _et al_[8] conducted a questionnaire survey on the PPG procedure in Japanese institutions. According to their report, the vagus nerve was preserved at 73.5% of the institutions, the infrapyloric artery was preserved in 49.4%, and partial dissection of the suprapyloric lymph nodes was performed in 56.2%. These differences in the procedure may affect postoperative gastric function after PPG, leading to postoperative symptoms.

INDICATIONS AND ONCOLOGIC SAFETY OF PPG

Since function-preserving surgeries such as PPG are usually less extensive, patient selection for these procedures should be carefully considered in terms of oncologic safety. In particular, in order to maintain pyloric cuff function with PPG, lymph nodes at the suprapyloric and infrapyloric stations may be incompletely dissected due to preservation of the right gastric artery, the infrapyloric artery, and the hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagus nerves[9-11].

In general, PPG is performed in patients who are preoperatively diagnosed with cT1N0M0 primary GC in the middle third of the stomach when the distal border of the tumor is approximately 4-5 cm away from the pylorus[9-12]. This indication is based on the incidence of lymph node metastasis in patients who have undergone conventional gastrectomy[13-16].

Kim _et al_[17] reported that the incidence of lymph node metastasis at the suprapyloric and infrapyloric stations in EGC located in the middle third of the stomach after PPG and conventional DG was 0.45% (1/220) and 0.45% (1/220), respectively. In addition, Kong _et al_[18] showed that the incidence of lymph node metastasis at the suprapyloric and infrapyloric stations in EGC located ≥ 5 cm from the pylorus was 0.46% (1/219) and 0.90% (2/221), respectively. Both studies also found that the mean number of suprapyloric lymph nodes dissected was significantly lower after PPG than that with conventional DG, but no significant difference was found for infrapyloric lymph nodes. However, incomplete dissection of lymph nodes at the suprapyloric station is considered acceptable because of the low incidence of metastasis. Therefore, patients who are clinically diagnosed with T1N0 disease could be candidates for PPG without suprapyloric lymph node dissection.

The five-year survival rate after PPG with modified D2 lymph node dissection ranges from 95% to 98%[10,11,19-21]. This rate is comparable to the five-year survival rate after gastric resection for EGC, which ranges from 90% to 98%[2,22,23]. In terms of oncologic safety, PPG seems reasonably safe for EGC when the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis can be assured.

POSTOPERATIVE SYMPTOMATIC OUTCOMES AFTER PPG

The advantage of PPG is the prevention of post-gastrectomy symptoms such as dumping syndrome and bile reflux gastritis, as well as reduced frequency of flatus. As shown in Table 1, the ratio of dumping syndrome and bile reflux gastritis was quite low in PPG compared to DG. However, delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after PPG resulting in patient-reported gastric fullness could be a disadvantage of PPG[21,24-30], which make PPG inappropriate in elderly patients and those with hiatus hernia or esophagitis[29,30]. The incidence of gastric stasis after PPG based on endoscopic studies ranges from 19% to 70%, compared to 13% to 36% after DG. Michiura _et al_[31] showed that food intake along with DGE was improved with time. Moreover, the reservoir function of the remnant stomach may promote better body weight (BW) recovery after PPG than after DG with Billroth I reconstruction[21,24,25,27,28].

Table 1 Postoperative symptomatic outcomes after pylorus-preserving surgery.

| Ref. | Procedure | No. of patients | Endoscopic findings (%) | Symptom (%) | Change of body weight (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagitis | Food residue | Bile reflux | Gastritis | Reflux | Fullness | Dumping | ||||

| Matsuki _et al_[21], 2012 | PPG | 433 | 11 | 19 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 94 | |

| Morita _et al_[24], 2013 | PPG | 408 | 6 | 28 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 92 |

| Ikeguchi _et al_[25], 2010 | PPG | 24 | 35 | 71 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 97 | ||

| DG-B1 | 30 | 26 | 16 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 90 | |||

| Park do _et al_[26], 2008 | PPG | 22 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 32 | ||||

| DG-B1 | 17 | 25 | 17 | 46 | 40 | |||||

| Nunobe _et al_[27], 2007 | PPG | 194 | 6 | 22 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 93.9 | |

| DG-B1 | 203 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 13 | 90.2 | ||

| Tomita _et al_[28], 2003 | PPG | 10 | 0 | 60 | 10 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 94.3 | |

| DG-B1 | 22 | 23 | 18 | 64 | 68 | 18 | 23 | 91.3 | ||

| Yamaguchi _et al_[29], 2004 | PPG | 28 | 61 | 28 | 20 | 44 | 12 | 94.6 | ||

| DG-B1 | 58 | 33 | 57 | 27 | 36 | 36 | 91.3 | |||

| Nakane _et al_[30], 2000 | PPG | 25 | 4 | 56 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 35 | 0 | 90 |

| DG-B1 | 25 | 8 | 36 | 40 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 93 |

Preserving the vagal nerve and the infrapyloric artery is thought to prevent gastric stasis[10,32,33], although these techniques have not been evaluated in randomized clinical trials. The length of the pyloric cuff is another important factor with regards to preservation of pyloric function. Nakane _et al_[34] reported that retaining a pyloric cuff of 2.5 cm results in a lower incidence of postoperative stasis compared to retaining a pyloric cuff of 1.5 cm as severe postoperative edema of the pyloric cuff might affect gastric wall motility after PPG. Morita _et al_[24] showed that retaining a pyloric cuff over 3 cm did not affect the incidence of postoperative stasis compared to retaining a pyloric cuff of less than 3 cm. At Japanese institutions, the retained pyloric cuff is usually between 2 and 4 cm[8,35]. Moreover, Hiki _et al_[6] argued that the infrapyloric and right gastric veins should be preserved to maintain blood flow in order to prevent postoperative edema of the pyloric cuff. Complete dissection of both veins could induce severe edema of the pyloric cuff, resulting in long-term postoperative retention of food in the residual stomach.

PG

The incidence of proximal GC has increased in recent years[36]. Total gastrectomy (TG) and PG with lymph node dissection are both performed for EGC located in the upper third of the stomach (U-EGC). In a retrospective study of Japanese institutions, Takiguchi _et al_[37] found that a quarter of the 586 patients with U-EGC underwent PG.

PG is generally thought to offer advantages over conventional TG with Roux-en-Y reconstruction in terms of retention of food in the remnant stomach. On the other hand, heartburn or gastric fullness due to esophageal reflux or gastric stasis is a potential disadvantage. However, these advantages and disadvantages depend on the reconstruction method used.

During the procedure, all regional nodes except the splenic hilar nodes (No. 10), the distal splenic nodes (No. 11d), the suprapyloric nodes (No. 5), and the infrapyloric nodes (No. 6) are dissected, although the dissection of the distal lesser curvature nodes (No. 3) and the right gastroepiploic artery (No. 4d) is incomplete. The hepatic and pyloric branches of the vagal nerve are preserved to maintain the function of the remnant stomach and pylorus as in PPG[7].

INDICATIONS AND ONCOLOGIC SAFETY OF PG

In general, to maintain both curability and functional capacity of the remnant stomach, PG is performed in patients who are preoperatively diagnosed with cT1N0M0 primary GC in the upper third of the stomach when at least half of the stomach can be preserved[38].

In patients undergoing PG, the lymph nodes in the lesser curvature (No. 3) and near the right gastroepiploic artery (No. 4d) are incompletely dissected. Thus, the surgical curability of GC may be lower with PG than with TG. However, Ooki _et al_[39] reported that proximal GC confined to the muscularis propria (mp) is not associated with lymph node metastasis at the right gastroepiploic artery (No. 4d), suprapyloric (No. 5), or infrapyloric (No. 6) stations. Sasako _et al_[40] reported that after curative gastrectomy, lymph node metastasis occurs at the suprapyloric and infrapyloric stations in patients with GC located in the upper third of the stomach in approximately 3% and 7% of cases, respectively. Although these percentages seem high, approximately half of the patients had T2 or more advanced GC and the incidence of metastasis may be lower in patients with EGC. Therefore, patients who are clinically diagnosed with T1N0 disease could be candidates for PG without dissection of the right gastroepiploic artery, suprapyloric, and infrapyloric lymph nodes.

The five-year survival rate after PG ranges from 90.5% to 98.5%[41-47]. Some studies have demonstrated that PG confers a survival benefit comparable to that of TG, the standard procedure for GC located in the upper third of the stomach[41,46-48]. Therefore, PG seems oncologically safe for EGC.

POSTOPERATIVE SYMPTOMATIC OUTCOMES AFTER PG

PG is generally thought to offer several advantages over conventional TG with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (Table 2). Ichikawa _et al_[49] reported that reduced food intake volume occurred less often in patients who underwent PG compared to TG. Masuzawa _et al_[41] reported that postoperative nutritional status as analyzed by blood tests such as serum albumin and hemoglobin was better after PG than TG. However, no studies have shown a superior outcome with PG as compared to TG in terms of postoperative BW, with the exception of one study which compared PG with jejunal interposition (JI) for reconstruction and TG at one year after surgery[41,42,47]. Moreover, compared to TG, PG was associated with a much higher rate of complications such as heartburn and anastomotic stenosis, which led An _et al_[47] to conclude that PG is not a better option for U-EGC than TG[46]. However, the reconstruction method was limited to esophagogastrostomy (EG) in these reports which did not demonstrate that PG was better. Therefore, the evaluation of other reconstruction methods is necessary.

Table 2 Postoperative symptomatic outcomes after proximal gastrectomy.

| Ref. | Procedure | No. of patients | Endoscopic findings (%) | Symptom (%) | Change of body weight (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagitis | Stenosis | Food residue | Reflux | Fullness | Dumping | ||

| Masuzawa _et al_[41], 2014 | PG-EG | 49 | 18 | 16 | 0 | 87 | |

| PG-JI | 32 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 86 | ||

| TG-RY | 122 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 85 | ||

| Nozaki _et al_[42], 2013 | PG-JI | 102 | 3 | 32 | 88 | ||

| TG-RY | 49 | 2 | 86 | ||||

| Katai _et al_[43], 2010 | PG-JI | 128 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 88.9 |

| Katai _et al_[44], 2003 | PG-JI | 45 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 88.5 | |

| Tokunaga _et al_[45], 2008 | PG-EG | 36 | 30 | ||||

| short-PG-JI | 18 | 9 | |||||

| long-PG-JI | 22 | 0 | |||||

| Ahn _et al_[46], 2013 | LAPG-EG | 50 | 32 | 12 | |||

| LATG-RY | 81 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| An _et al_[47], 2008 | PG-EG | 89 | 29 | 38 | 86.4 | ||

| TG-RY | 334 | 2 | 7 | 87.4 | |||

| Yoo _et al_[48], 2004 | PG-EG | 74 | 16 | 35 | |||

| TG-RY | 185 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| Tokunaga _et al_[50], 2009 | PG-EG | 38 | 8 | 3 | 86 | ||

| PG-JI | 45 | 9 | 22 | 86 | |||

| Ahn _et al_[52], 2013 | LAPG-EG | 50 | 8 | 32 | 94 | ||

| LAPG-DT | 43 | 5 | 49 | 5 | 12 | 96.3 | |

| Nomura _et al_[53], 2014 | PG-JI | 10 | 10 | 0 | 30 | 91.2 | |

| PG-DT | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 87.1 |

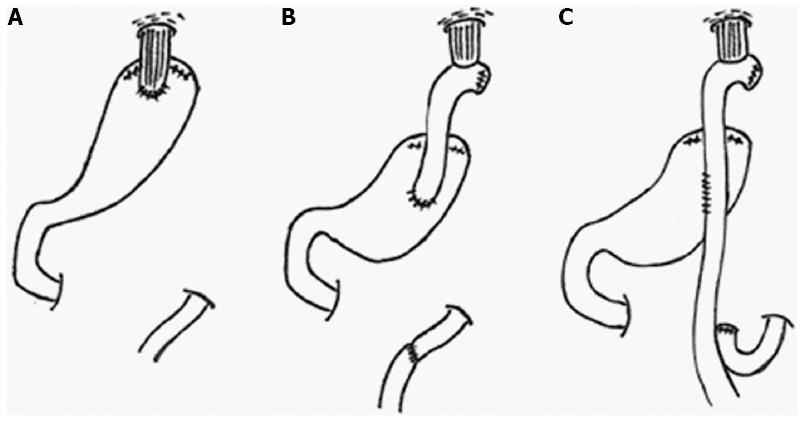

Currently, three procedures, TG with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TG-RY), PG-EG, and PG-JI, are widely used to treat U-EGC in Japan (Figure 2, Table 3)[37]. Double tract (DT) reconstruction and jejunal pouch reconstruction have also been used in a small number of patients. A survey of Japanese institutions regarding reconstruction methods after PG showed that the most frequently used method was EG (48%), followed by JI (28%), DT (13%), and pouch reconstruction (7%)[35].

Figure 2 Reconstruction methods after proximal gastrectomy. A: Esophagogastrostomy; B: Jejunum interposition; C: Double tract.

Table 3 Comparison of the reconstruction methods after proximal gastrectomy.

| PG-EG | PG-JI | PG-DT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage | Short operation time | Low incidence of reflux esophagitis | Low incidence of reflux esophagitis |

| Low incidence of DGE | |||

| Disadvantage | High incidence of reflux esophagitis | Long operation time | Long operation time |

| High incidence of anastomotic stenosis | High incidence of DGE | Sometimes difficult for endoscopic evaluation of remnant stomach |

PG-EG is the simplest procedure since there is a single anastomotic site, but it is associated with a high incidence of reflux esophagitis[46,47]. PG-JI may prevent regurgitation of the gastric contents, resulting in a lower incidence of reflux esophagitis, but the procedure is slightly complicated. Several studies have compared the postoperative outcomes of PG-EG and PG-JI. The incidence of esophageal reflux as evaluated by endoscopic findings and symptoms was reported to be lower after PG-JI compared to PG-EG[41,45]. However, the questionnaire conducted by Tokunaga _et al_[50] showed that abdominal fullness was more frequently observed after PG-JI than after PG-EG, because the interposed jejunum may prevent the smooth passage of food. The length of interposed jejunum is important in preventing esophageal reflux, but a longer length may induce abdominal fullness.

The other important problem after PG is remnant GC (RGC). Ohyama _et al_[51] reported that RGC was observed in 5% of 316 patients after PG. They also showed that advanced RGC was more likely in patients after PG-JI with a longer length of interposed jejunum (> 15 cm) or PG-DT, and cancer-related death was only observed in patients who underwent these reconstruction methods. Tokunaga _et al_[45] reported that endoscopic evaluation of the remnant stomach could not be performed in 50% of patients after PG-JI with interposed jejunum > 10 cm, compared to 22% in patients after PG-JI with interposed jejunum ≤ 10 cm. They concluded that a length of 10 cm or shorter is preferable for endoscopic evaluation of the remnant stomach. The type of reconstruction chosen after PG should facilitate postoperative endoscopic examinations for early detection and treatment of RGC.

PG-DT has been attempted to improve postoperative outcomes after PG. PG-DT has three anastomotic sites; esophagojejunostomy, jejunogastrostomy and jejunojejunostomy. The length of interposed jejunum is from 10 to 20 cm between esophagojejunostomy and jejunogastrostomy, and about 20 cm between jejunogastrostomy and jejunojejunostomy. Food passes through the remnant stomach or the jejunum by two routes in PG-DT. PG-DT is thought to offer the same advantages as PG-JI, including the prevention of esophageal reflux, but it is expected to be better than PG-JI with regards to DGE, because an alternative route for food exists if DGE occurs. Only a few studies have analyzed postoperative outcomes after PG-DT. Ahn _et al_[52] evaluated postoperative complications after PG-DT compared to PG-EG; they concluded that PG-DT is a feasible, simple, and novel method. They showed that the incidence of anastomotic stenosis and reflux symptoms was lower after PG-DT than PG-EG and BW was better maintained. Nomura _et al_[53] evaluated postoperative outcomes after PG-DT vs PG-JI. Although their study had a small sample size, they showed that the BW ratio was significantly higher in the PG-JI group than in the PG-DT group. The incidence of esophageal reflux was 10% in both groups. Further studies are needed to assess the clinical utility of PG-DT.

CONCLUSION

Function-preserving surgery has already been performed in some of the high volume institutions in Japan and South Korea, and it seems to be useful in terms of postoperative quality of life and oncologic safety. However, indications should be carefully considered, because function-preserving surgery usually involves less extensive procedures, resulting in the possibility of inadequate treatment for more deeply invasive tumors. Preoperative evaluation is very important in selecting the appropriate candidates for function-preserving surgery.

Laparoscopy-assisted PPG and PG has several advantages over conventional PPG and PG in terms of reduced intraoperative blood loss, postoperative pain and fast recovery from invasive surgery[54,55]. Since some studies reported that the oncological curability was assured[33,56,57], laparoscopic function-preserving gastrectomy is considered to be feasible by surgeons with sufficient experience in laparoscopic gastrectomy.

Many retrospective studies have shown the usefulness of function-preserving surgery, but there has been no consensus to adopt function-preserving surgery as the standard of surgery. To establish function-preserving surgery as the gold standard for patients with EGC, prospective randomized controlled trials that compare PPG or PG with conventional gastrectomy and evaluate survival and postoperative quality of life are necessary.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Kakushima N, Lim JB, Teoh AYB, Yamamoto H S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

| 1. | Sano T, Hollowood A. Early gastric cancer: diagnosis and less invasive treatments. Scand J Surg. 2006;95:249-255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 4. | Maki T, Shiratori T, Hatafuku T, Sugawara K. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy as an improved operation for gastric ulcer. Surgery. 1967;61:838-845. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 5. | Sawai K, Takahashi T, Suzuki H. New trends in surgery for gastric cancer in Japan. J Surg Oncol. 1994;56:221-226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 13. | Kodama M, Koyama K. Indications for pylorus preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer located in the middle third of the stomach. World J Surg. 1991;15:628-633; discussion 633-634. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 16. | Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Kanemitsu Y, Shimizu Y, Hirai T, Yasui K, Morimoto T, Kato T. Lymph node metastasis in cancer of the middle-third stomach: criteria for treatment with a pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Surg Today. 2001;31:196-203. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 22. | Sano T, Sasako M, Kinoshita T, Maruyama K. Recurrence of early gastric cancer. Follow-up of 1475 patients and review of the Japanese literature. Cancer. 1993;72:3174-3178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 23. | Sue-Ling HM, Johnston D, Martin IG, Dixon MF, Lansdown MR, McMahon MJ, Axon AT. Gastric cancer: a curable disease in Britain. BMJ. 1993;307:591-596. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 29. | Yamaguchi T, Ichikawa D, Kurioka H, Ikoma H, Koike H, Otsuji E, Ueshima Y, Shioaki Y, Lee CJ, Hamashima T. Postoperative clinical evaluation following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:883-886. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 30. | Nakane Y, Akehira K, Inoue K, Iiyama H, Sato M, Masuya Y, Okumura S, Yamamichi K, Hioki K. Postoperative evaluation of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:590-595. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 32. | Sawai K, Takahashi T, Fujioka T, Minato H, Taniguchi H, Yamaguchi T. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy with radical lymph node dissection based on anatomical variations of the infrapyloric artery. Am J Surg. 1995;170:285-288. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 36. | Salvon-Harman JC, Cady B, Nikulasson S, Khettry U, Stone MD, Lavin P. Shifting proportions of gastric adenocarcinomas. Arch Surg. 1994;129:381-388; discussion 388-389. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 39. | Ooki A, Yamashita K, Kikuchi S, Sakuramoto S, Katada N, Hutawatari N, Watanabe M. Clinical significance of total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2875-2883. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 40. | Sasako M, McCulloch P, Kinoshita T, Maruyama K. New method to evaluate the therapeutic value of lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1995;82:346-351. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 49. | Ichikawa D, Ueshima Y, Shirono K, Kan K, Shioaki Y, Lee CJ, Hamashima T, Deguchi E, Ikeda E, Mutoh F. Esophagogastrostomy reconstruction after limited proximal gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1797-1801. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|