Clinical features of gastroduodenal injury associated with long-term low-dose aspirin therapy (original) (raw)

Editorial Open Access

Copyright ©2013 Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited. All rights reserved.

World J Gastroenterol. Mar 21, 2013; 19(11): 1673-1682

Published online Mar 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1673

Clinical features of gastroduodenal injury associated with long-term low-dose aspirin therapy

Junichi Iwamoto, Yoshifumi Saito, Akira Honda, Yasushi Matsuzaki, Department of Gastroenterology, Tokyo Medical University, Ibaraki Medical Center, Ibaraki 300-0395, Japan

ORCID number: $[AuthorORCIDs]

Author contributions: All the authors contributed equally to this work; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Correspondence to: Junichi Iwamoto, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, Tokyo Medical University, Ibaraki Medical Center, 3-20-1 Ami-machi Chuo, Inashiki-gun, Ibaraki 300-0395, Japan. junnki@dg.mbn.or.jp

Telephone: +81-298-871161 Fax: +81-298-883463

Received: September 14, 2012

Revised: December 3, 2012

Accepted: December 15, 2012

Published online: March 21, 2013

Processing time: 188 Days and 20.5 Hours

Abstract

Low-dose aspirin (LDA) is clinically used for the prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events with the advent of an aging society. On the other hand, a very low dose of aspirin (10 mg daily) decreases the gastric mucosal prostaglandin levels and causes significant gastric mucosal damage. The incidence of LDA-induced gastrointestinal mucosal injury and bleeding has increased. It has been noticed that the incidence of LDA-induced gastrointestinal hemorrhage has increased more than that of non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced lesions. The pathogenesis related to inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 includes reduced mucosal flow, reduced mucus and bicarbonate secretion, and impaired platelet aggregation. The pathogenesis related to inhibition of COX-2 involves reduced angiogenesis and increased leukocyte adherence. The pathogenic mechanisms related to direct epithelial damage are acid back diffusion and impaired platelet aggregation. The factors associated with an increased risk of upper gastrointestinal (GI) complications in subjects taking LDA are aspirin dose, history of ulcer or upper GI bleeding, age > 70 years, concomitant use of non-aspirin NSAIDs including COX-2-selective NSAIDs, and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Moreover, no significant differences have been found between ulcer and non-ulcer groups in the frequency and severity of symptoms such as nausea, acid regurgitation, heartburn, and bloating. It has been shown that the ratios of ulcers located in the body, fundus and cardia are significantly higher in bleeding patients than the ratio of gastroduodenal ulcers in patients taking LDA. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of developing gastric and duodenal ulcers. In contrast to NSAID-induced gastrointestinal ulcers, a well-tolerated histamine H2-receptor antagonist is reportedly effective in prevention of LDA-induced gastrointestinal ulcers. The eradication of H. pylori is equivalent to treatment with omeprazole in preventing recurrent bleeding. Continuous aspirin therapy for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding may increase the risk of recurrent bleeding but potentially reduces the mortality rates, as stopping aspirin therapy is associated with higher mortality rates. It is very important to prevent LDA-induced gastroduodenal ulcer complications including bleeding, and every effort should be exercised to prevent the bleeding complications.

- Citation: Iwamoto J, Saito Y, Honda A, Matsuzaki Y. Clinical features of gastroduodenal injury associated with long-term low-dose aspirin therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(11): 1673-1682

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i11/1673.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1673

INTRODUCTION

Low-dose aspirin (LDA) is clinically used for the prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events with the advent of an aging society[1-6]. Worldwide trials of antiplatelet therapy have demonstrated that an antiplatelet regimen (such as aspirin 75-325 mg/d) offers worthwhile protection against myocardial infarction, stroke, and death.

On the other hand, a very low dose of aspirin (10 mg daily) decreases the gastric mucosal prostaglandin levels and causes significant gastric mucosal damage[7]. The incidence of LDA-induced gastrointestinal (GI) mucosal injury has increased[8-11]. This review focuses on the clinical characteristics of LDA-induced GI ulcer or erosion and bleeding, including incidence, mechanism, risk of bleeding, clinical manifestations, risk factors, endoscopic features, prevention, and treatment.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF LDA-INDUCED GI INJURY

Incidence of LDA-induced GI ulcer and bleeding

The incidence of upper GI damage in patients taking long-term LDA has been investigated. In a multicenter investigation, Yeomans _et al_[12] found that the prevalence rates of ulcer and erosion were 10.7% and 63.1%, respectively, in 187 patients taking long-term LDA, and that the incidence rates of ulcer and erosion in 113 patients followed up for 3 mo were 7.1% and 60.2%, respectively, indicating that GI ulcers develop in one in 10 patients taking LDA.

The annual incidence of serious upper GI ulcer bleeding among Japanese patients taking LDA or non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) was investigated. The pooled incidence rate of bleeding was 2.65% (range: 2.56%-2.74%) and 1.29% (range: 1.27%-1.31%) per 1000 patient years for LDA and non-aspirin NSAID users, respectively[13]. Niv _et al_[14] have investigated, using esophagogastroduodenoscopy, 46 asymptomatic patients taking LDA and they detected ulcer or erosions in 22 patients, erosive gastroduodenitis in 13, gastric ulcer in 14, duodenal ulcer in 2, and gastric and duodenal ulcers in 2, suggesting that esophagogastroduodenoscopy is important for LDA users, even the asymptomatic patients. The incidence and factors influencing the occurrence of upper GI bleeding in 903 consecutive patients taking LDA were analyzed. The results revealed that 4.5% of patients presented with upper GI bleeding requiring hospitalization during follow-up, and the incidence of upper GI bleeding was 1.2 per 100 patient years[9]. The incidence rates of upper GI bleeding in 27 694 users of LDA were analyzed, and a total of 207 exclusive users of LDA experienced a first episode of upper GI bleeding. The standardized incidence rate of upper GI bleeding among LDA users was 2.6% (range: 2.2%-2.9%), and the standardized incidence rate for combined use of LDA and other NSAIDs was 5.6% (range: 4.4%-7.0%)[10].

The frequency of gastroduodenal injuries associated with LDA use for prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events were investigated. The results showed that mucosal injuries occurred in 61.4% and gastroduodenal ulcers in 18.8% of 101 LDA users with ischemic heart disease who were not receiving antiulcer treatment[15]. In another investigation, screening upper endoscopic examinations were prospectively performed on 236 patients with ischemic heart disease, and mucosal defects were found in 92 of 190 (48.4%) users of LDA and in 6 of 46 (13.0%) non-users[16].

Taha _et al_[17] have investigated the efficacy of famotidine in prevention of peptic ulcers and erosive esophagitis in patients receiving LDA. They showed that gastric ulcers had developed in 3.4% of patients treated with famotidine and in 15.0% of patients on placebo, while duodenal ulcers had developed in 0.5% and 8.5%, respectively. Other previous reports have examined the efficacy of esomeprazole as compared with placebo in prevention of peptic ulcers in patients who were at risk for ulcer development taking low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA). These studies have shown that esomeprazole significantly reduced the cumulative proportion of patients with peptic ulcers, and that 7.4% of placebo recipients developed peptic ulcers[18]. These studies have revealed not only the efficacy of famotidine or esomeprazole but also the incidence of gastroduodenal ulcer in patients taking long-term LDA without anti-ulcer drugs.

A clinical investigation examined the efficacy of low-dose lansoprazole in the secondary prevention of LDA-associated gastric or duodenal ulcers, and showed that the cumulative incidence of gastric or duodenal ulcers was 3.7% in the lansoprazole group and 31.7% in the placebo group. This investigation indicated that the incidence of gastric or duodenal ulcers was 31.7% in patients with a definite history of gastric or duodenal ulcers who required long-term LDA therapy[19].

The incidence rates of upper GI events in LDA users are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Incidence of upper gastrointestinal events in low-dose aspirin users.

| Ref. | Subjects | GI event | Incidence rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeomans _et al_[12] | 187 | Gastroduodenal | 10.7% |

| Gastroduodenal | 63.1% | ||

| Ishikawa _et al_[13] | 1657 | Gastroduodenal | 2.65 (95%CI: 2.56-2.74) per 1000 patient years |

| Niv _et al_[14] | 46 asymptomatic | Gastroduodenal ulcer or erosion | 47.83% |

| Taha _et al_[17] | 200 | Gastroduodenal ulcer | 23.5% |

| Scheiman _et al_[18] | 2426 high risk | Gastroduodenal ulcer | 7.4% |

| Sugano _et al_[19] | 235 with a history of ulcer | Gastroduodenal ulcer | 31.7% |

| Serrano _et al_[9] | 903 | Upper GI bleeding | 1.2 per 100 patient years |

| Sorensen _et al_[10] | 27 694 | Upper GI bleeding | 2.6 (95%CI: 2.2-2.9) |

| Nema _et al_[15] | 101 | Gastroduodenal mucosal injury | 61.4% |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer | 18.8% | ||

| Nema _et al_[16] | 190 | Gastroduodenal mucosal defects | 48.4% |

Mechanism of LDA-induced gastroduodenal mucosal damage

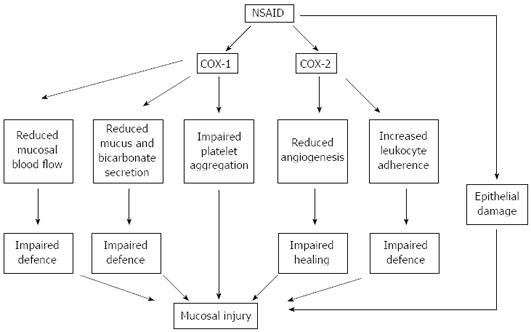

The mechanism of action of NSAIDs or LDA can be subdivided into local action and systemic action, and several mechanisms have been reported in a previous review[20] (Figure 1). The pathogenesis related to inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 includes reduced mucosal flow, reduced mucus and bicarbonate secretion, and impaired platelet aggregation. The pathogenic mechanisms involved in inhibition of COX-2 are reduced angiogenesis and increased leukocyte adherence. The pathogenesis related to direct epithelial damage involves acid back diffusion and impaired platelet aggregation. Aspirin is a more potent inhibitor of COX-1 than of COX-2[20] (Figure1).

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastric injury. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs induce injury via three key pathways: inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 activity, inhibition of COX-2 activity, and direct cytotoxic effects on the epithelium. Aspirin is a more potent inhibitor of COX-1 than of COX-2[20].

Both the direct effect of aspirin on the GI mucosa and the systemic effect related to reduction of prostaglandin level are suggested to contribute in the pathogenesis of LDA-induced GI mucosal damage[7]. Some researchers have suggested that reduction in the ability of the gastric mucosa to synthesize prostaglandin E2 and the consequent side effects result in injury of the gastric mucosa following aspirin use[21].

Gastric damage in rats induced by a selective COX-1 inhibitor (SC-560) and a selective COX-2 inhibitor (celecoxib) were investigated. SC-560 alone or celecoxib alone did not cause gastric damage, whereas the combination of SC-560 and celecoxib invariably caused hemorrhagic erosion. This study suggested that inhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 is required for NSAID-induced gastric injury in the rat[22].

Another study demonstrated that COX-1-deficient mice survived well and had no gastric pathology, indicating that inhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 was required for NSAID-induced gastric injury[23].

A previous review has suggested a mechanism of LDA-induced gastroduodenal mucosal injury, claiming that ion trapping and back diffusion of hydrogen ions lead to gastric erosion and bleeding; this is known as the hypothesis of NSAIDs’ dual insult on the stomach[24].

It has been suggested that NSAID-induced neutrophil adherence is associated with NSAID-induced GI mucosal damage. The neutrophil adherence to the vascular endothelium could lead to obstruction in the capillaries with consequent reduction of blood flow in the gastric mucosa. The increased production of oxygen-derived free radicals and the liberation of proteases are also associated with NSAID-induced mucosal damage[25].

Risk of upper GI injury and bleeding associated with long-term use of LDA

A previous investigation has evaluated the long-term effects of individual doses of aspirin (10 mg, 81 mg, or 325 mg daily for 3 mo) on the GI tract, and revealed that a very low dose of aspirin (10 mg daily) decreased the gastric mucosal prostaglandin levels and caused significant gastric mucosal damage[7].

Other researchers studied the characteristics of patients with acute upper GI hemorrhage at 3 time points over a 6-year follow-up period, and revealed that the incidence of hemorrhage in patients taking LDA increased from 15 per 100 000 of the population per annum to 18 and 27, and that the respective incidence rates in patients taking other anti-thrombotic drugs were 4, 8, and 12, respectively. On the other hand, no significant change was found in NSAID users. This study has suggested that the rate of LDA-induced GI hemorrhage is higher than that of non-aspirin NSAID-induced lesions[26]. A previous case-control study demonstrated that the percentages of regular users of aspirin regimens (300 mg daily or less) among patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer bleeding, hospital and community controls were 12.8%, 9.0%, and 7.8%, respectively, concluding that the regular users of aspirin regimens were at risk for gastric or duodenal ulcer bleeding[27].

A case-control study in Japan has shown that the odds ratio (OR) of upper GI bleeding was 5.5 for aspirin and 6.1 for non-aspirin NSAIDs, indicating that the risk of upper GI bleeding in the cases taking LDA is almost similar to the risk in the cases taking non-aspirin NSAIDs[28].

A meta-analysis of 24 randomized controlled trials has evaluated the incidence of GI hemorrhage associated with long-term aspirin therapy to determine the effect of dose reduction and formulation on the incidence of hemorrhage. This meta-analysis revealed that GI hemorrhage occurred in 2.47% of patients taking aspirin as compared with 1.42% taking placebo. This study suggested that long-term therapy with aspirin is associated with a significant increase in the incidence of GI hemorrhage, and no evidence was found supporting the proposal that reducing the dose or using modified release formulations would reduce the incidence of GI hemorrhage[29]. Another meta-analysis of 6 trials investigated the benefits and GI risk of aspirin use for secondary prevention of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases. It was shown that aspirin reduced all-cause mortality by 18%, the number of strokes by 20%, myocardial infarctions by 30%, and other vascular events by 30%. It was further demonstrated that patients who took aspirin were 2.5 times more likely than those in the placebo group to have GI tract bleeding, concluding that aspirin use for secondary prevention of thromboembolic events has a favorable benefit-to-risk profile[30].

A previous investigation has demonstrated that following percutaneous coronary intervention, long-term (one year) clopidogrel therapy significantly reduced the risk of adverse ischemic events, indicating the efficacy of clopidogrel therapy in such cases[31].

The risk of major upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with various antiplatelet drugs has been examined, and the results revealed that the individual risks of upper GI bleeding were 4.0% (range: 3.2%-4.9%) with acetylsalicylic acid, 2.3% (range: 0.9%-6.0%) with clopidogrel, 0.9% (range: 0.4%-2.0%) with dipyridamole, and 3.1% with ticlopidine (range: 1.8%-5.1%), suggesting that not only acetylsalicylic acid but also the other various antiplatelet drugs have some risk for upper GI bleeding[32].

The risk of upper GI bleeding following the combined use of LDA and other antithrombotic drugs has been investigated. Hallas _et al_[33] have assessed the risk of serious upper GI bleeding in patients taking LDA alone or in combination with other antithrombotic drugs. This investigation demonstrated that the adjusted odds ratios associating drug use with upper GI bleeding were 1.8 (range: 1.5-2.1) for LDA, 1.1 (range: 0.6-2.1) for clopidogrel, 1.9 (range: 1.3-2.8) for dipyridamole, and 1.8 (range: 1.3-2.4) for vitamin K antagonists. Furthermore, they have shown that the adjusted odds ratios associated with combined use were 7.4 (range: 3.5-15) for clopidogrel and aspirin, 5.3 (range: 2.9-9.5) for vitamin K antagonists and aspirin, and 2.3 (range: 1.7-3.3) for dipyridamole and aspirin[33]. The higher risk of upper GI bleeding in patients receiving LDA and other antithrombotic drugs was revealed.

Risk factors for LDA-induced GI damage and bleeding

A previous investigation demonstrated that at doses below 163 mg/d, GI hemorrhage occurred in 2.30% of patients taking aspirin as compared with 1.45% taking placebo, and that with modified release formulations of aspirin, the odds ratio was 1.93, indicating that reducing the dose or using modified release formulations would not reduce the incidence of GI hemorrhage[29].

Another report examined the association between taking LDA and the risk of symptomatic ulcer. The authors demonstrated that the relative risk was 2.9 (range: 2.3-3.6) for aspirin (75 mg) users as compared with non-users, and that the relative risk was similar for doses up to 300 mg daily[34].

On the other hand, a multivariate analysis examined the risk factors for LDA-related upper GI bleeding, and showed that higher doses of aspirin increased the risk of upper GI bleeding, suggesting a dose-dependent risk for aspirin[9].

A multicenter case-control study investigated 550 incident cases of upper GI bleeding admitted into hospital with melena or hematemesis and confirmed by endoscopy, in comparison with 1202 controls identified from population census lists about the use of aspirin. This study demonstrated that the relative risks of upper GI bleeding for plain, enteric-coated, and buffered aspirin at average daily doses of 325 mg or less were 2.6, 2.7, and 3.1, respectively, and at doses greater than 325 mg, the relative risk was 5.8 for plain and 7.0 for buffered aspirin[35]. Another investigation disclosed that the risk of upper GI bleeding was similar among users of non-coated LDA and coated LDA[10]. It was also suggested in another study that the risk of gastroduodenal ulcer was similarly elevated for both regular and enteric-coated preparations of LDA[34]. These clinical reports revealed no important differences in risk among the three aspirin forms.

Some studies have been designed to identify patients who are most likely to have adverse events of NSAID therapy. The established risk factors for development of NSAID-associated gastroduodenal ulcers were reportedly advanced age, history of ulcer, concomitant use of corticosteroids, higher dose of NSAID including the use of more than one NSAID, concomitant administration of anticoagulants, and serious systemic disorders, while possible risk factors were reportedly concomitant infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), cigarette smoking, and consumption of alcohol[36].

The risk factors for upper GI bleeding or peptic ulcer in patients taking LDA have been suggested in a previous investigation. A clinical study evaluated the risk predictors of gastroduodenal ulcers during treatment with vascular protective doses of aspirin, and suggested that older age and H. pylori infection increased the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers[12].

A multivariate analysis examined the risk factors for LDA-related upper GI bleeding, and showed that a history of peptic ulcer or upper GI bleeding correlated with higher risk of upper GI bleeding. On the other hand, antisecretory and nitro-vasodilator drugs correlated with a decreased risk[9]. It has been suggested that the factors associated with an increased risk of upper GI complications in subjects taking LDA are aspirin dose, history of ulcer or upper GI bleeding, age > 70 years, concomitant use of non-aspirin NSAIDs including COX-2-selective NSAIDs, and H. pylori infection[8].

A previous cohort study investigated the incidence rates of upper GI bleeding in 27 694 users of LDA as compared with the incidence rates in the general population. This study disclosed that the standardized incidence rate ratio was 2.6 (range: 2.2-2.9), and the standardized incidence rate ratio for combined use of LDA and other NSAIDs was 5.6 (range: 4.4-7.0), indicating the higher risk of combined use of LDA and other NSAIDs[10].

Many investigators have reported the relationship between H. pylori infection and use of NSAIDs in the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer, and this is still controversial. A meta-analysis of 25 studies has shown that both H. pylori infection and use of NSAIDs independently and significantly increase the risk of peptic ulcer and ulcer bleeding, concluding that there is synergism for the development of peptic ulcer and ulcer bleeding between H. pylori infection and NSAID use[37]. Another previous study investigated whether H. pylori increases the risk of upper GI bleeding in patients taking LDA, evaluating the role of H. pylori infection and other clinical factors. The results revealed that H. pylori infection was an independent risk factor of upper GI bleeding in this population (OR: 4.7, range: 2.0-10.9)[38]. On the other hand, another previous report has demonstrated that _H. pylori_-infected patients were less likely to have any gastric erosion than the non-infected, indicating that H. pylori infection may partially protect against LDA-induced gastric erosion[39].

A previous case-control study investigated the risk of peptic ulcer and upper GI bleeding associated with the use of coxibs, traditional NSAIDs, aspirin, or combinations of these drugs. This study demonstrated that the risk associated with coxib use for upper GI bleeding was less than that of non-selective NSAIDs. This report revealed that with combined use of LDA, the lower risk of coxibs tended to disappear[40]. The Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study has shown that for patients not taking aspirin, the annual incidence rates of upper GI ulcer complications alone and combined with symptomatic ulcers for celecoxib were 0.44% and 1.40%, respectively, and for patients taking aspirin, the corresponding rates were 2.01% and 4.70%, respectively. These results suggested that celecoxib was associated with a lower incidence of GI toxicity, but that the risk increased with concomitant use of LDA[41].

Although coxibs tend to present a lower risk of upper GI complications than NSAIDs overall, aspirin is a strong effect modifier, abolishing completely the GI safety advantage of coxibs over NSAIDs, suggesting that concomitant use of COX-2 inhibitor and LDA increases the risk of upper GI complications[42].

Clinical manifestations of LDA-induced gastroduodenal injury

Previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between clinical manifestations and ulcers in patients taking LDA. In a multicenter investigation, Yeomans _et al_[12] demonstrated that the ulcer prevalence was 10.7% in 187 patients taking long-term LDA, and that only 20% had dyspeptic symptoms, which was not significantly different from the patients without ulcer. This study revealed no significant differences between the ulcer groups and non-ulcer groups in the frequency and severity of symptoms such as nausea, acid regurgitation, heartburn, and bloating[12]. Another previous report stated that some patients on aspirin complained of symptoms whereas the others remained completely asymptomatic, indicating that the patients remaining free of symptoms seemed to characteristically have a higher gastric sensory threshold[43]. Niv _et al_[14] have investigated 46 asymptomatic patients taking mini-dose aspirin for more than 3 mo. Ulcer or erosions developed in 22 of those patients taking mini-dose aspirin, erosive gastroduodenitis in 13, gastric ulcer in 14, duodenal ulcer in 2, and gastric and duodenal ulcers in 2, indicating a high prevalence of ulcerations of the stomach and duodenum in asymptomatic LDA users[14].

The mechanism of asymptomatic ulceration in aspirin users has been investigated, and it was suggested that subjects on aspirin remaining free of symptoms appear to characteristically have higher gastric sensory thresholds[43].

Endoscopic features of LDA-induced gastroduodenal mucosal damage

A recent investigation has examined the chronological changes of the GI mucosa with LDA use in 20 healthy _H. pylori_-negative subjects. These patients were divided into those receiving 100 mg aspirin with placebo, and those receiving 100 mg aspirin + 300 mg rebamipide daily for 7 d, and they were examined for mucosal damage at 0, 2, 6, and 24 h on the first day, and then on the third and seventh days. The results revealed that ulcers developed in the duodenum at 24 h and in the antrum at 72 h, and that erosions mainly developed in the duodenum in the subjects receiving 100 mg aspirin, concluding that damage occurred in the duodenum most frequently and that almost all damage improved gradually in spite of continuous aspirin[44]. A prospective study on 238 patients with bleeding peptic ulcers demonstrated the endoscopic characteristics of LDA-induced hemorrhagic ulcer. Non-NSAID-induced ulcers were significantly higher in the gastric body than the LDA-induced ulcers, and non-aspirin NSAID-induced ulcers and most of the LDA-induced ulcers were found in the gastric body, angular notch, and duodenum. The number of ulcers was investigated in 18 non-aspirin NSAID-induced ulcers, and the ulcer was single in 44.4% and multiple in 55.6%[11]. In our previous investigation, the ratios of ulcers located in the antrum of patients taking LDA and non-aspirin NSAIDs were significantly higher than those of patients not taking NSAIDs (the bleeding patients and the whole gastroduodenal ulcer patient population). It also has been shown that the ratios of ulcers located in the body, fundus, and cardia were significantly higher in the bleeding patients than in the whole gastroduodenal ulcer patient population taking LDA[45]. Shiotani _et al_[46] investigated 305 patients taking 100 mg aspirin for cardiovascular diseases. They found that 38 patients (12.4%) had ulcer lesions (34 gastric ulcer, 2 duodenal ulcer, and 2 with gastroduodenal ulcer). Of the 34 gastric ulcers, 18 were single and 16 were multiple, and 58.8% of the gastric ulcers were in the gastric body while the maximum ulcer size was 25 mm[46].

Some investigators analyzed the size of LDA-induced ulcers, and demonstrated that gastric ulcers were more frequent than duodenal ulcers in both _H. pylori_-negative and -positive patients; the gastric ulcers and duodenal ulcers were most commonly 5-10 mm in size[47]. In a study on 674 upper GI bleeders, erosive esophagitis was detected in 150 cases, suggesting that erosive esophagitis is common in patients with upper GI bleeding taking LDA or antithrombotic agents[48].

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF LDA-INDUCED GASTRODUODENAL MUCOSAL DAMAGE

Prevention of LDA-induced gastroduodenal mucosal damage and bleeding

The primary prevention of LDA-induced gastroduodenal damage has been investigated. It was demonstrated that famotidine is effective in prevention of gastric and duodenal ulcers, as well as erosive esophagitis, in patients taking LDA[17]. In contrast to NSAID-induced GI ulcers, a well-tolerated histamine H2-receptor antagonist is effective in preventing the development of LDA-induced GI ulcers.

A previous study investigated the efficacy of esomeprazole in reducing the risk of gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients receiving continuous LDA therapy. The results revealed that 5.4% in the placebo group developed a gastric or duodenal ulcer during the 26-wk treatment as compared with 1.6% in the esomeprazole group, suggesting that esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) reduces the risk of developing gastric and duodenal ulcers[47]. Another clinical trial revealed that treatment with esomeprazole (40 mg or 20 mg once daily) reduces the occurrence of peptic ulcers in LDA-taking patients who are at risk for ulcer development[18].

The secondary prevention of LDA-induced gastroduodenal damage has been investigated. A case-control study demonstrated that proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, and nitrates reduced upper GI bleeding risk, suggesting that antisecretory agents or nitrate treatment results in reduced relative risks of upper GI bleeding in patients taking NSAIDs or aspirin[49]. A clinical trial involving 160 patients with aspirin-related peptic ulcers/erosions compared the efficacy of H2-receptor antagonists (famotidine group) and proton pump inhibitors (pantoprazole group). This trial demonstrated that GI bleeding was significantly more frequent in the famotidine group than in the pantoprazole group[50]. A clinical investigation in Japan examined the efficacy of low-dose lansoprazole (15 mg once daily) in the secondary prevention of LDA-associated gastric or duodenal ulcers. The patients were randomized to receive lansoprazole 15 mg daily (n = 226) or gefarnate 50 mg twice daily (n = 235) for 12 mo or longer. The results disclosed that the cumulative incidence of gastric or duodenal ulcers was 3.7% in the lansoprazole group and 31.7% in the placebo group, indicating that lansoprazole was superior to gefarnate for the secondary prevention of LDA-associated gastric or duodenal ulcers[19]. After the ulcers had healed, the patients who were negative for H. pylori were randomly assigned to receive either 75 mg of clopidogrel daily plus placebo or 80 mg of aspirin daily plus 20 mg of esomeprazole twice daily for 12 mo. The results showed that recurrent ulcer bleeding occurred in 13 patients receiving clopidogrel and in 1 receiving aspirin plus esomeprazole. This study concluded that among patients with a history of aspirin-induced ulcer bleeding, aspirin plus esomeprazole was superior to clopidogrel in the prevention of recurrent ulcer bleeding in _H. pylori_-negative patients[51]. The studied co-treatments for prevention of LDA-induced gastroduodenal events are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 Prevention of low-dose aspirin-induced gastroduodenal events.

| Ref. | Co-treatment | GI event | Incidence rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taha _et al_[17] | Famotidine 40 mg vs placebo | Gastric ulcers/duodenal ulcers | 3.4% vs 15.0% |

| 0.5% vs 8.5% | |||

| Scheiman _et al_[18] | Esomeprazole 40 mg vs 20 mg vs placebo | Gastroduodenal ulcers | 1.5% vs 1.1% vs 7.4% |

| Sugano _et al_[19] | Lansoprazole 15 mg vs placebo | Gastroduodenal ulcers | 3.7% vs 31.7% |

| Yeomans _et al_[47] | Esomeprazole 20 mg vs placebo | Gastroduodenal ulcers | 1.6% vs 5.4% |

| Ng _et al_[50] | Famotidine 40 mg vs pantoprazole 20 mg | Dyspeptic or bleeding ulcers/erosions | 20% vs 0% |

| Chan _et al_[67] | Omeprazole 20 mg vs H. pylori eradication | Gastroduodenal bleeding | 0.9% vs 1.9% |

| Lai _et al_[68] | H. pylori eradication + lansoprazole 15 mg vs H. pylori eradication | Gastroduodenal ulcers | 1.6% vs 14.8% |

Treatment of LDA-induced gastroduodenal injury and bleeding

It has been reported that ranitidine with NSAID discontinuation is effective in the treatment of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcer[52]. If it is not possible to stop NSAID treatment, rabeprazole should be used as its efficacy for NSAID-induced ulcer under continuous NSAID administration has been confirmed[53].

Many investigations have studied the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in the healing of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcer in comparison with the efficacy of H2-receptor antagonists. Most of the reports stated that the proton pump inhibitors healed and prevented ulcers more effectively than H2-receptor antagonists[54-56]. An animal experiment revealed that lansoprazole protection against NSAID-induced gastric damage depends on a reduction in mucosal oxidative injury, which is also responsible for an increase in sulfhydryl radical bioavailability[57].

Another previous report stated that the differences between the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment of NSAID-induced ulcer were not statistically significant[58].

In patients with LDA-induced upper GI bleeding, the risk involved in stopping the LDA was higher than that of non-aspirin NSAID. A previous study compared the therapeutic effects of proton pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists on the healing rate of gastroduodenal ulcers during continuous use of LDA, and no significant differences were found. The results indicated that not only proton pump inhibitors but also H2-receptor antagonists are effective in the treatment of gastroduodenal ulcers during continuous use of LDA[59,60].

Previous research has also revealed that misoprostol is effective for the treatment of gastroduodenal injury in patients taking NSAIDs or LDA[61-63].

It is a clinical problem whether aspirin therapy should be continued or discontinued in patients who develop peptic ulcer bleeding while receiving LDA. A clinical trial examined whether discontinuation of aspirin therapy is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and compared the frequency of aspirin therapy discontinuation during four weeks before an ischemic cerebral event in patients and four weeks before interview in controls. This trial suggested the importance of continuous aspirin therapy and clarified the risk associated with discontinuation of aspirin therapy in patients at risk for ischemic stroke[64]. A recent clinical investigation has analyzed the recurrent ulcer bleeding and mortality rates attributable to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in 78 patients receiving aspirin and 78 taking placebo for 8 wk immediately after endoscopic therapy. It was demonstrated that recurrent ulcer bleeding rate within 30 d was 10.3% in the aspirin group and 5.4% in the placebo group. The patients who received aspirin had lower all-cause mortality rates than the patients who received placebo (1.3% vs 12.9%), while the patients in the aspirin group had lower mortality rates attributable to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or GI complications than the patients in the placebo group (1.3% vs 10.3%). This study suggested that continuous aspirin therapy may increase the risk of recurrent bleeding but potentially reduces the mortality rates, indicating that continuous aspirin therapy had lower mortality rates[65].

Our previous study has revealed that the ratios of patients taking LDA who required additional endoscopic treatment on the next day following the first procedure were higher than those of non-aspirin NSAID and non-NSAID patients. The duration of hospitalization of the patients taking LDA was significantly longer than that of the patients taking non-aspirin NSAIDs and non-NSAIDs. These results suggested the possibility that the treatment of LDA-induced hemorrhagic gastroduodenal ulcers is more difficult than treatment of those induced by non-aspirin NSAIDs or non-NSAIDs, indicating that every effort should be exercised to prevent bleeding complications in patients receiving LDA[45]. Endoscopic high-frequency soft coagulation has been recently developed in Japan, and the efficacy of hemostasis with soft coagulation for bleeding gastric ulcer patients (including aspirin users) has been investigated by comparing it with hemoclips. The results demonstrated that 85% of patients in the endoscopic hemostasis with soft coagulation group and 79% patients in the endoscopic hemoclipping group were successfully treated[65]. Another clinical investigation involved 39 cases where hemostasis was attempted with bipolar forceps to deal with non-variceal upper GI bleeding. This study revealed that the technique of bipolar forceps (a new technique of endoscopic hemostasis) is simple, safe and unlikely to induce complications[66]. Although standard endoscopic hemostasis is reportedly difficult for upper GI bleeding in aspirin users, this new technique of endoscopic hemostasis is potentially effective in such cases[45,65,66].

Eradication of H. pylori in treatment of LDA-induced gastroduodenal damage

A meta-analysis has investigated the prevalence of H. pylori infection and NSAID use in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding, and revealed that H. pylori infection increased the risk (3.53-fold) of peptic ulcer disease in NSAID takers, in addition to the risk associated with NSAID use, concluding that both H. pylori infection and NSAID use independently and significantly increase the risk of peptic ulcer and ulcer bleeding[37].

A previous report demonstrated that among those taking aspirin, the probability of recurrent bleeding during a 6-mo period was 1.9% for patients who received eradication therapy and 0.9% for patients who received omeprazole, indicating that eradication of H. pylori is equivalent to treatment with omeprazole in preventing recurrent bleeding. On the other hand, omeprazole is superior to eradication of H. pylori in preventing recurrent bleeding in patients who are taking non-aspirin NSAIDs[67].

However, in another study, after the ulcers had healed and the H. pylori infection was eradicated, the patients were randomly assigned to treatment with 30 mg of lansoprazole daily or placebo, in addition to 100 mg of aspirin daily, for 12 mo. The results revealed that the treatment with lansoprazole in addition to eradication of H. pylori infection significantly reduced the rate of recurrence of ulcer complications[68].

CONCLUSION

Worldwide trials of antiplatelet therapy have demonstrated that an antiplatelet regimen (75-325 mg/d) offers worthwhile protection against myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. On the other hand, the rate of low-dose aspirin-induced GI hemorrhage has increased more than that of non-aspirin NSAID-induced lesions. Continuous aspirin therapy in the case of GI bleeding may increase the risk for recurrent bleeding but potentially reduces mortality rates. Although the size of gastroduodenal ulcers in patients taking LDA is smaller than that of patients taking non-aspirin NSAIDs, more cases need additional endoscopic treatment on the next day after the first procedure as compared with patients taking non-aspirin NSAIDs. Previous clinical investigation has suggested that co-treatment with proton pump inhibitors is effective in preventing the development of LDA-induced GI ulcer. These results indicate that it is very important to prevent LDA-induced gastroduodenal ulcer complications including bleeding, and that every effort should be exercised to prevent bleeding complications.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer Rocha JBT S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zhang DN

References

| 3. | Lauer MS. Clinical practice. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1468-1474. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 4. | Lorenz RL, Schacky CV, Weber M, Meister W, Kotzur J, Reichardt B, Theisen K, Weber PC. Improved aortocoronary bypass patency by low-dose aspirin (100 mg daily). Effects on platelet aggregation and thromboxane formation. Lancet. 1984;1:1261-1264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 5. | Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2. ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1988;2:349-360. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 13. | Ishikawa S, Inaba T, Mizuno M, Okada H, Kuwaki K, Kuzume T, Yokota H, Fukuda Y, Takeda K, Nagano H. Incidence of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Japan. Acta Med Okayama. 2008;62:29-36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 19. | Sugano K, Matsumoto Y, Itabashi T, Abe S, Sakaki N, Ashida K, Mizokami Y, Chiba T, Matsui S, Kanto T. Lansoprazole for secondary prevention of gastric or duodenal ulcers associated with long-term low-dose aspirin therapy: results of a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, double-dummy, active-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:724-735. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

|---|

| 40. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, Gomollón F, Feu F, González-Pérez A, Zapata E, Bástida G, Rodrigo L, Santolaria S. Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer bleeding associated with selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, traditional non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and combinations. Gut. 2006;55:1731-1738. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 339] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

|---|

| 41. | Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, Whelton A, Makuch R, Eisen G, Agrawal NM, Stenson WF. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA. 2000;284:1247-1255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2166] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2030] [Article Influence: 81.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

|---|

| 44. | Kawai T, Yamagishi T, Goto S. Circadian variations of gastrointestinal mucosal damage detected with transnasal endoscopy in apparently healthy subjects treated with low-dose aspirin (ASA) for a short period. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16:155-163. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 45. | Iwamoto J, Mizokami Y, Shimokobe K, Ito M, Hirayama T, Saito Y, Ikegami T, Honda A, Matsuzaki Y. Clinical features of gastroduodenal ulcer in Japanese patients taking low-dose aspirin. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2270-2274. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 49. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, Bujanda L, Gomollón F, Forné M, Aleman S, Nicolas D, Feu F, González-Pérez A. Effect of antisecretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:507-515. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 223] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

|---|

| 53. | Mizokami Y. Efficacy and safety of rabeprazole in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced ulcer in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5097-5102. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 54. | Campbell DR, Haber MM, Sheldon E, Collis C, Lukasik N, Huang B, Goldstein JL. Effect of H. pylori status on gastric ulcer healing in patients continuing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy and receiving treatment with lansoprazole or ranitidine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2208-2214. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 55. | Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhász L, Rácz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ, Swannell AJ, Hawkey CJ. A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid Suppression Trial: Ranitidine versus Omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:719-726. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 56. | Agrawal NM, Campbell DR, Safdi MA, Lukasik NL, Huang B, Haber MM. Superiority of lansoprazole vs ranitidine in healing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastric ulcers: results of a double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. NSAID-Associated Gastric Ulcer Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1455-1461. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 57. | Blandizzi C, Fornai M, Colucci R, Natale G, Lubrano V, Vassalle C, Antonioli L, Lazzeri G, Del Tacca M. Lansoprazole prevents experimental gastric injury induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs through a reduction of mucosal oxidative damage. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4052-4060. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 62. | Sontag SJ, Schnell TG, Budiman-Mak E, Adelman K, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, Roth SH, Ipe D, Schwartz KE. Healing of NSAID-induced gastric ulcers with a synthetic prostaglandin analog (enprostil). Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1014-1020. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

|---|

| 65. | Arima S, Sakata Y, Ogata S, Tominaga N, Tsuruoka N, Mannen K, Shiraishi R, Shimoda R, Tsunada S, Sakata H. Evaluation of hemostasis with soft coagulation using endoscopic hemostatic forceps in comparison with metallic hemoclips for bleeding gastric ulcers: a prospective, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:501-505. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

|---|