The role of kinematics in cortical regions for continuous human motion perception (original) (raw)

The world is a fluid, ever-changing stream of ongoing activity and movement that the brain must transform into an understanding of intent. How this transformation takes place is a complex problem that can be approached in a bottom-up fashion by exploring the kinematic properties of actions and the brain areas responsive to these properties. The actions in question are the actual physical movements that people perform in order to achieve their intent or goal (Baldwin, Andersson, Saffran, & Meyer, 2008). Much of the research in this area has taken the approach of measuring perceptual judgments or brain activity while presenting contrasting classes of simple elemental movements (e.g., walking and running), utilizing brief video displays or impoverished representations of actions in the form of point-light displays and geometric shapes (cf. Grosbras, Beaton, & Eickhoff, 2012, for a recent meta-analysis). Only a handful of studies have examined the processing of an on-going stream of activity over longer durations (Baldwin et al., 2008; Baldwin, Baird, Saylor & Clark, 2001; Zacks, Kumar, Abrams, & Mehta, 2009) and related this observation to brain activity (Schubotz, Korb, Schiffer, Stadler, & von Cramon, [2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR47 "Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

"); Zacks, Swallow, Vettel, & McAvoy, [2006](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR62 "Zacks, J. M., Swallow, K. M., Vettel, J. M., & McAvoy, M. P. (2006). Visual motion and the neural correlates of event perception. Brain Research, 1076, 150–162.")). However, these studies neglected to investigate how cortical areas respond to relevant kinematics while viewing human activity. In the present research, we directly explored how the kinematics of observed continuous actions relates to brain activity in cortical regions previously established as areas for the general processing of human action and motion. Our approach closely approximated the processes involved in natural viewing.Studies comparing different classes of elemental actions with differing kinematics have provided insight into what motion properties relate to judgments in behavioral experiments. For example, studies of male versus female point-light walking movements have revealed the relative contributions of form and motion in judging gender from point-light walkers (Kozlowski & Cutting, [1977](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR37 "Kozlowski, L. T., & Cutting, J. E. (1977). Recognizing sex of a walker from a dynamic point-light display. Perception & Psychophysics, 21, 575–580. doi: 10.3758/BF03198740

"); Mather & Murdoch, [1994](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR39 "Mather, G., & Murdoch, L. (1994). Gender discrimination in biological motion displays based on dynamic cues. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 258, 273–279."); Pollick, Kay, Heim, & Stringer, [2005](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR44 "Pollick, F. E., Kay, J. W., Heim, K., & Stringer, R. (2005). Gender recognition from point-light walkers. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 31, 1247–1265."); Troje, [2002](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR53 "Troje, N. F. (2002). Decomposing biological motion: A framework for analysis and synthesis of human gait patterns. Journal of Vision, 2(5), 371–387. doi:

10.1167/2.5.2

")). In addition, studies of affective door-knocking movements have shown how the velocity of the wrist can explain the structure of affective judgments from point-light arms (Johnson, McKay, & Pollick, [2011](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR33 "Johnson, K. L., McKay, L. S., & Pollick, F. E. (2011). He throws like a girl (but only when he’s sad): Emotion affects sex-decoding of biological motion displays. Cognition, 119, 265–280."); Pollick, Paterson, Bruderlin, & Sanford, [2001](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR45 "Pollick, F. E., Paterson, H. M., Bruderlin, A., & Sanford, A. J. (2001). Perceiving affect from arm movement. Cognition, 82, B51–B61.")). Examination of ongoing activity has been explored in the context of animacy displays (Heider & Simmel, [1944](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR29 "Heider, F., & Simmel, M. (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. The American Journal of Psychology, 57, 243–259.")) that investigated what motion properties inform the recognition of intent from two geometric objects interacting. Blythe, Todd, and Miller ([1999](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR6 "Blythe, P. W., Todd, P. M., & Miller, G. F. (1999). How motion reveals intention: Categorizing social interactions. In G. Gigerenzer, P. M. Todd, & the ABC Research Group (Eds.), Simple heuristics that make us smart (pp. 257–285). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.")) used a computational analysis to show that seven kinematic features distilled from the trajectories were sufficient to categorize the type of interaction between the two objects. These cues were velocity, relative distance, relative angle, relative heading, absolute velocity, absolute vorticity (change in heading), and relative vorticity. Similarly, Zacks ([2004](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR60 "Zacks, J. M. (2004). Using movement and intentions to understand simple events. Cognitive Science, 28, 979–1008.")) showed that kinematic properties could be related to the way in which observers perceived event boundaries in an animacy display. Event boundaries have been proposed as a means for understanding ongoing activity, first developed in infancy (Baldwin et al., [2001](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR4 "Baldwin, D. A., Baird, J. A., Saylor, M. M., & Clark, M. A. (2001). Infants parse dynamic action. Child Development, 72, 708–717."); Newtson, [1976](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR42 "Newtson, D. (1976). Foundations of attribution: The perception of ongoing behavior. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. F. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (pp. 223–248). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum."); Zacks, Tversky, & Iyer, [2001](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR63 "Zacks, J. M., Tversky, B., & Iyer, G. (2001). Perceiving, remembering, and communicating structure in events. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 130, 29–58. doi:

10.1037/0096-3445.130.1.29

"); Zacks, [2004](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR60 "Zacks, J. M. (2004). Using movement and intentions to understand simple events. Cognitive Science, 28, 979–1008.")). Movement features, including velocity and acceleration of the animated shapes, predicted when observers perceived event boundaries and influenced action comprehension (see also Hard, Recchia, & Tversky, [2011](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR28 "Hard, B. M., Recchia, G., & Tversky, B. (2011). The shape of action. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 140, 586–604.")).Zacks, Kumar, Abrams, and Mehta (2009) explored key motion properties for event boundary perception in natural scenes, using video displays (mean duration = 370 s) of an actor performing common actions: for instance, a man sitting at a desk paying bills. On the basis of previous regression analyses from simplified motion displays (Zacks, 2004; Zacks et al., 2006), they investigated motion properties including changes in the speeds, positions, and acceleration of the actor’s two arms and head, and the relative changes between the pairwise combinations. Motion properties were indeed correlated with the event boundaries perceived by the observer: The most significant predictors of event boundaries were the speed and acceleration of body parts and the relative distances between the left hand and other body parts. This left-hand bias was partially explained by the saliency of the vision of that hand: The actor was left-handed, and the hand was always closer to the viewer. This study showed that, behaviorally, in natural displays, the perception of event boundaries is predictable via changes in the bottom-up processing of the low-level motion properties.

Studies of brain activity during human motion observation have revealed a variety of brain regions specialized for this purpose. Research into how we obtain meaning and intention from observed action have revealed two networks involving substantial frontal, parietal, and temporal regions (Van Overwalle & Baetens, 2009). One of these networks has been indicated to be involved in theory of mind (ToM) and involves medial prefrontal cortex and temporo-parietal cortex (Amodio & Frith, 2006; C. D. Frith & Frith, [1999](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR17 "Frith, C. D., & Frith, U. (1999). Interacting minds—A biological basis. Science, 286, 1692–1695. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1692

")). The other network has been associated with mirror neurons and involves the inferior frontal gyrus and the inferior parietal cortex (Rizzolatti & Sinigaglia, [2010](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR46 "Rizzolatti, G., & Sinigaglia, C. (2010). The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: Interpretations and misinterpretations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 264–274.")). Although these two networks appear to be involved with more complex processing of actions, other regions in temporal cortex have been shown to be involved with processing aspects of the form and motion of an action (Grosbras et al., [2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR25 "Grosbras, M. H., Beaton, S., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2012). Brain regions involved in human movement perception: A quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 33, 431–454.")). The areas associated with selectivity to processing of form include the extrastriate body area (EBA; Downing, Jiang, Shuman, & Kanwisher, [2001](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR13 "Downing, P. E., Jiang, Y. H., Shuman, M., & Kanwisher, N. (2001). A cortical area selective for visual processing of the human body. Science, 293, 2470–2473.")) and the fusiform body area (FBA; Peelen & Downing, [2005](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR43 "Peelen, M. V., & Downing, P. E. (2005). Selectivity for the human body in the fusiform gyrus. Journal of Neurophysiology, 93, 603–608.")). These regions respond to photorealistic displays of bodies and body parts, with evidence showing that the representation is more part-based in EBA than in FBA (Downing & Peelen, [2011](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR14 "Downing, P. E., & Peelen, M. V. (2011). The role of occipitotemporal body-selective regions in person perception. Cognitive Neuroscience, 2, 186–203.")). Areas associated with processing motion include the human motion complex (hMT+), and the posterior region of the superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), which has been demonstrated to be more active when viewing intact displays of biological motion than when viewing scrambled displays (Beauchamp, Lee, Haxby, & Martin, [2002](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR5 "Beauchamp, M. S., Lee, K. E., Haxby, J. V., & Martin, A. (2002). Parallel visual motion processing streams for manipulable objects and human movements. Neuron, 34, 149–159."); Grossman & Blake, [2002](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR26 "Grossman, E. D., & Blake, R. (2002). Brain areas active during visual perception of biological motion. Neuron, 35, 1167–1175.")). It is important to point out, though, that the relationship between individual brain areas and larger networks is not fully clear: For example, pSTS is largely considered part of the ToM network (Castelli, Happé, Frith, & Frith, [2000](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR10 "Castelli, F., Happé, F., Frith, U., & Frith, C. (2000). Movement and mind: A functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. NeuroImage, 12, 314–325."); U. Frith & Frith, [2010](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR18 "Frith, U., & Frith, C. (2010). The social brain: Allowing humans to boldly go where no other species has been. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society B, 365, 165–176. doi:

10.1098/rstb.2009.0160

")), whereas it is also considered the visual input of the mirror neuron network (see Iacoboni & Dapretto, [2006](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR31 "Iacoboni, M., & Dapretto, M. (2006). The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 942–951. doi:

10.1038/nrn2024

")). Likewise, recent evidence has pointed to considerable overlap of hMT+ with EBA (Ferri, Kolster, Jastorff, & Orban, [2013](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR15 "Ferri, S., Kolster, H., Jastorff, J., & Orban, G. A. (2013). The overlap of the EBA and the MT/V5 cluster. NeuroImage, 66, 412–425."); Weiner & Grill-Spector, [2011](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR57 "Weiner, K. S., & Grill-Spector, K. (2011). Not one extrastriate body area: Using anatomical landmarks, hMT+, and visual field maps to parcellate limb-selective activations in human lateral occipitotemporal cortex. NeuroImage, 56, 2183–2199.")), suggesting that hMT+ may be more attuned to the integration of human motion and form than had previously been thought (Ferri et al., [2013](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR15 "Ferri, S., Kolster, H., Jastorff, J., & Orban, G. A. (2013). The overlap of the EBA and the MT/V5 cluster. NeuroImage, 66, 412–425."); Gilaie-Dotan, Bentin, Harel, Rees, & Saygin, [2011](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR21 "Gilaie-Dotan, S., Bentin, S., Harel, M., Rees, G., & Saygin, A. P. (2011). Normal form from biological motion despite impaired ventral stream function. Neuropsychologia, 49, 1033–1043.")). Ultimately, however, research has collectively suggested that cognitive aspects of human motion and action interpretation are performed by fronto-parietal networks, whereas early visual processing of human movement comprises dorsal regions sensitive to motion and ventral regions sensitive to form. This role of frontal areas was furthered explored by Schubotz et al. ([2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR47 "Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi:

10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

")) using extended natural displays of human activity (mean duration = 81 s). Comparing intention-driven displays (e.g., laundry) with purely human motion displays (e.g., tai chi movements), and using scrambled point-light versions as controls, they found that only when displays allowed previous knowledge of intent, as opposed to knowledge of movement (i.e., laundry > tai chi), were fronto-parietal networks invoked, suggesting top-down modulation in order to comprehend intent (Schubotz et al., [2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR47 "Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi:

10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

"); Zacks, [2004](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR60 "Zacks, J. M. (2004). Using movement and intentions to understand simple events. Cognitive Science, 28, 979–1008.")). However, as expected, the perception of human movement did show activation in hMT+ relative to the control stimuli.To move beyond simply identifying activated cortical regions, studies using long display durations have examined the relationship of the kinematic properties of animated movement to brain activity. For example, Dayan et al. (2007) investigated how brain activity is modulated by viewing the different relationships between the speed and shape of 9-s movements. Dayan et al. produced displays of a cloud of points moving in an elliptical trajectory, in which the cloud of points either did or did not move with the natural covariation of speed and shape suggested by the 1/3 power law between speed and local curvature. The researchers found that, regardless of the speed–shape relation, a bilateral fMRI signal increase was apparent in posterior visual areas, including occipito-temporal cortex and bilateral inferior parietal lobe. However, when the speed–shape relation was natural, they found activation in bilateral STS/superior temporal gyrus and in bilateral posterior cerebellum. Using simple animations of two interacting geometric objects, Zacks, Swallow, Vettel, and McAvoy (2006) reported that speed, the distance between objects, and relative speed were related to the fMRI response in areas including hMT+. They also showed that activity in hMT+ and pSTS increased at times that observers identified event boundaries. Similarly Jola et al. (2013) found that fMRI activity in these regions was correlated among a group of observers when they watched a 6-min-long solo dance. Jola et al. suggested that this activity might result from observers synchronizing their brain activity to the motion of the dancer. One possibility is that hMT+ and pSTS both perform human motion analyses and play a bottom-up role in action perception. However, Zacks et al. (2006) used simple geometric stimuli that were quite impoverished relative to live-action movies of human activity. Everyday activity incorporates much additional information, such as nonrigid articulation, and it may be that the relationship between hMT+, pSTS, and observed kinematics may dissipate when such additional information is freely available, despite the behavioral percept remaining largely intact (Zacks et al., 2009).

The present study extends these previous results by exploring the relationship between a set of kinematic properties of a viewed naturalistic movement and brain activity as revealed via fMRI. Our visual stimuli consisted of two extended live-action movies, taken from Zacks et al. (2009), of an actor performing two activities: (a) “playing with Duplo (Lego)” and (b) “paying bills.” We conducted analyses at both the whole-brain level and the region-of-interest (ROI) level, focusing on areas previously highlighted: pSTS and hMT+. Furthermore, an additional ROI, the fusiform face area (FFA), was studied. The FFA is specialized for the processing and recognition of faces (Kanwisher, McDermott, & Chun, 1997; Sergent, Ohta, & MacDonald, 1992), and thus would not be expected to be greatly influenced by motion. We proposed that in regions relating to motion processing, BOLD activity would be predicted by changes in the speed and acceleration of the actor’s limbs. Furthermore, we expected this relationship to be found in both the ROI and whole-brain analyses, with the whole-brain analysis revealing additional areas that might be involved in processing observed natural actions. No change in neural activation of the FFA related to the motion properties of the actor was expected.

Method

Participants

A group of 12 participants (six male, six female; mean age = 22.25, SD = 2.83) were recruited from the University of Glasgow Subject Pool. All participants self-reported being right-handed and neurologically healthy. They were paid £30 in total for their participation. Ethics permission was granted from the Ethics Board of the Faculty of Information and Mathematical Sciences, University of Glasgow.

Stimuli

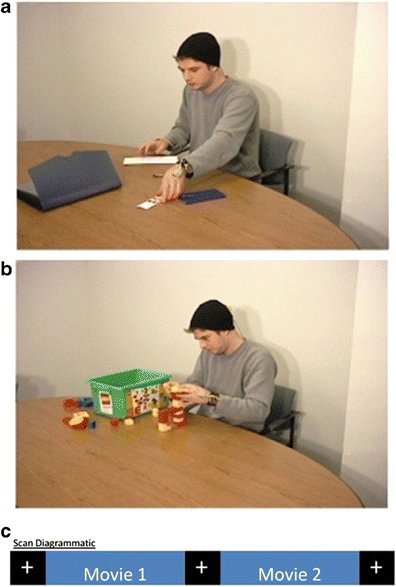

The stimuli for the functional scan consisted of two movies taken from the set previously described by Zacks et al. (2009). In brief, both movies depicted one man performing common activities at a table: (a) the actor paid a set of bills (Fig. 1a, “Bills”); (b) the actor built model figures using Duplo blocks (www.lego.com) (Fig. 1b, “Duplo”). The displays lasted 371 and 388 s, respectively. Three markers for motion tracking were visible on the head and hands of the actor during the displays. These allowed for magnetic motion tracking (www.ascension-tech.com) of the actor’s movements for later analysis of their kinematic properties in a three-dimensional (3-D) space.

Fig. 1

One frame from each of the displayed experimental movies. a Taken from the display showing the actor paying bills. b Taken from the display showing the actor building a model with Duplo blocks

Image acquisition

The participants were scanned using a 3-T Siemens TimTrio MRI scanner (Erlangen, Germany). They completed two scanning sessions lasting approximately 1 h each, separated by a break period of ~30 min, during which the participant was removed from the scanner. Both sessions contained anatomical image acquisition of the whole-brain structure via a 3-D magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient recalled echo (MP-RAGE) T1-weighted sequence (192 slices, 1-mm3 isovoxel, TR = 1,900 ms, TE = 2.52, 256 × 256 image resolution). The sessions included the functional scans described here as well as others that comprised a separate experiment.

Functional and localizer scans were divided up between sessions: Session 1 consisted of the functional scan for seeing the two movies (echo-planar 2-D imaging: PACE-MoCo, TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 30 ms, 32 sagittal slices (near whole-brain), 3-mm3 isovoxel, 70 × 70 matrix, 391 volumes), as well as an hMT+ localizer (like the previous scan; 182 volumes) and a pSTS localizer (like the previous scan; 245 volumes). Session 2 consisted of two unreported functional scans and the FFA localizer (like the previous scan, except TR = 3,000 ms, TE = 30 ms; 152 volumes).

Functional scan

The two displays (“Bills” and “Duplo”) were presented to participants in the scanner via NordicNeuroimagingLab presentation goggles (www.nordicneuroimgaginglab.com). The goggles had a viewing area of 800 (width) × 600 (height) pixels, covering 30 × 22.5 deg of visual angle. Both displays were presented in one functional scan with 10 s of fixation (white cross on a uniform black background) separating the displays. A further 10 s of fixation was presented immediately prior to the onset of the first display and immediately postoffset of the second display. The order of the displays within the run was pseudorandomized across participants: Four participants saw “Duplo” first in the sequence. Timing and display presentation were controlled via Presentation (www.neurobs.com). The participants viewed all displays passively.

Functional localizers

hMT+

hMT+ is defined as a region in the lateral posterior cortex where brain activation is stronger to dynamic than to static displays (Tootell et al., 1995) and is neither shape-sensitive (Albright, 1984; Zeki, 1974) nor contrast-sensitive (Beauchamp et al., 2002; Huk & Heeger, 2002; Zacks et al., 2006). To identify hMT+, a block-design paradigm, in line with previous reports (Beauchamp et al., 2002; Swallow, Braver, Snyder, Speer, & Zacks, 2003; Zacks et al., 2006), was used with stimuli that alternated between a high-contrast static black-and-white circular checkerboard pattern, and a low-contrast dynamic circular dot display constructed from alternating concentric circles of black and white dots. The static checkerboard subtended 21.6 deg of visual angle and alternated between two versions of the same image 15 times over 30 s, with the black and white segments of the checkerboard switching locations across images. The total span of the moving dot display was equivalent to that of the static display. Each dot within the moving display was 2 × 2 pixels. The dynamic display contracted and expanded every 1.5 s, with each block of dynamic display lasting 30 s. In total, five blocks of both dynamic and static images were shown, with periods of baseline before and after the initial and final blocks. The block order was fixed across participants and always alternated from static to dynamic. All images were presented on a uniform gray background. No task was given other than to attend the displays and maintain fixation. Participants completed two runs of this 400-s hMT+ localizer. Prior to starting, participants were asked to confirm that they could indeed perceive the low-contrast dynamic display.

The localization analysis was carried out at the single-subject level using BrainVoyager QX (2.1) in a standardized atlas space (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988). hMT+ was defined as voxels that (a) survived the contrast of dynamic greater than static (p < .005 uncorrected), (b) had a continuous area greater than 108 mm2 (3 mm isotropic voxels), and (c) were within a restricted anatomical region (Zacks et al., 2006).

pSTS

pSTS was defined as a region located in the lateral posterior cortex that responded more strongly to coherent than to scrambled biological motion. A block-design paradigm was used to localize pSTS, alternating blocks of coherent and scrambled biological motion with periods of fixation (Beauchamp et al., 2002; Grossman & Blake, 2002; Grossman et al., [2000](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR27 "Grossman, E., Donnelly, M., Price, R., Pickens, D., Morgan, V., Neighbor, G., & Blake, R. (2000). Brain areas involved in perception of biological motion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12, 711–720. doi: 10.1162/089892900562417

"); Zacks et al., [2006](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR62 "Zacks, J. M., Swallow, K. M., Vettel, J. M., & McAvoy, M. P. (2006). Visual motion and the neural correlates of event perception. Brain Research, 1076, 150–162.")). Coherent biological motion displays (black dots on a uniform gray background) were created using 12 marker points on virtual actors as they performed actions such as walking and jumping; scrambled biological motion displays were created by perturbing the initial point positions. The images subtended a viewing angle of 9.45 (width) × 15 (height) deg. During the fixation intervals, participants viewed a black cross on a uniform gray background. Each motion stimulus block lasted 16 s, consisting of eight pairs of a 1-s display followed by a 1-s blank screen, with ten repetitions per condition. The block orders within runs were fixed: Run 1 was in the order coherent–scrambled–baseline, and Run 2 was in the reverse order. Blocks were separated by 2 s of blank screen, with 10 s of fixation before commencing the first block. A fixation cross was displayed centrally throughout. No task was given other than to attend the displays and maintain fixation. Participants completed two runs of this 490-s pSTS localizer.pSTS was defined as voxels that (a) survived the contrast of coherent greater than scrambled motion (p < .005 uncorrected), (b) had a continuous area greater than 108 mm2 (3-mm isotropic voxels), and (c) were within a restricted anatomical region (Zacks et al., 2006). Given the proximity of pSTS and hMT+, any overlapping voxels were removed from both regions to achieve region-specific voxels.

FFA

A final block-design paradigm was incorporated in order to localize cortical regions sensitive to face perception. Participants viewed alternating blocks of faces, houses, and noise; the noise patterns were constructed from the two other conditions (Vizioli, Smith, Muckli, & Caldara, 2010). All images were shown as uniform gray presented on a white background, and measured 11.25 deg of visual angle: Faces were cropped using an elliptical annulus in order to remove neck, ears, and hairline from the images.

Blocks of the three categories lasted for 18 s and were made up of 20 image presentations lasting 750 ms, separated by 250 ms of blank white screen. Five blocks of each category were shown. A fixation cross on a uniform background was displayed for 12 s at the commencement of each run, and also separated each condition block. Participants completed two runs of the FFA localizer, each lasting 456 s, using a fixed order: (1) faces–noise–houses and (2) the reverse order. No task was given other than to attend the displays and maintain fixation.

FFA was defined as voxels that (a) survived the contrast of faces greater than houses (p < .005 uncorrected), (b) had a continuous area greater than 108 mm2 (3-mm isotropic voxels), and (c) were located around the mid-fusiform-gyrus (Kanwisher et al., 1997; McCarthy, Puce, Gore, & Allison, 1997).

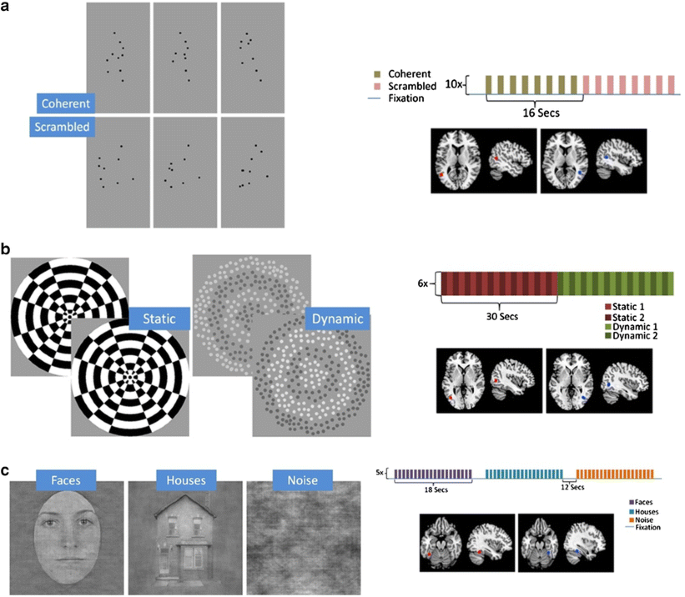

A summary of the locations and extents of the ROIs in the 12 participants can be seen in Table 1, and a schematic depiction of all localizer stimuli and regions of activation can be seen in Fig. 2.

Table 1 Localizer summary: Summary positional coordinates and cluster sizes of group activation from the three functional localizer scans. pSTS, posterior superior temporal sulcus; hMT+, human motion complex; FFA, fusiform face area; n, number of participants who showed activation at given contrast

Fig. 2

Frames from each condition of the three functional localizers, with a schematic diagram of the paradigm and diagrams of the locations of mean activation on a generic normalized brain atlas. a Posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) paradigm. b human motion complex (hMT+) paradigm. c Fusiform face area (FFA) paradigm. Talairach coordinates are as in Table 1

fMRI data analysis

Two separate analyses were performed to characterize the relations between movement features and brain activity, one using the functionally localized regions of interest, and the other using a voxel-wise whole-brain approach.

ROI

All functional and anatomical images were analyzed using BrainVoyager QX 2.1 (Brain Innovations, Maastricht, Netherlands). Functional images were initially preprocessed via slice scan-time correction (cubic-spline interpolation) and temporal high-pass filtering in order to remove low-frequency nonlinear drifts. An additional 3-D motion correction (trilinear interpolation) was used to remove head motion: The translation correction never exceeded 3 mm. All images were transformed into Talairach stereotaxic space (Talairach & Tournoux, 1988) by initially coaligning all functional images to the first volume of the functional run closest to the relevant anatomical run. The two session anatomical scans were then coaligned via intersession alignment methods within BrainVoyager, resulting in all functional images being registered to the stereotaxic space.

For each ROI, in all participants, the mean time course of the region during each display was extracted and a linear model predicting brain activity from four movement variables was fitted. Four variables were selected, in order to minimize multicollinearity and degrees of freedom while retaining as much as possible of the variance in the movement signals. The 3-D positional coordinates of the actor were tracked using magnetic sensors attached to the actor’s hands and head. On the basis of stepwise regression models from previous research informing the most relevant parameters for anthropomorphized motion analysis (Zacks, 2004; Zacks et al., 2009; Zacks et al., 2006), the selected variables were:

- the distance between each pair of body parts (i.e., left hand, right hand and head),

- the speed of each body part (the norm of the first derivative of position),

- the relative speed of each pair of body parts (the first derivative of distance), and

- the relative acceleration of each pair of body parts (the second derivative of distance).

For example, if the actor were to have his left hand resting on his head and then reach for a pen on the table, the movement variables would change as follows. The distance between the hand and head would increase. The speed of the left hand would increase from zero, and then decrease as the hand approached the pen. The relative speed between the left hand and the head would likewise increase from zero, then decrease. The relative acceleration of the left hand and head would initially be zero, then would be positive as the hand sped up, and then would turn negative as the hand slowed, approaching the pen.

The left hand, right hand, and head each had a speed feature, and each of the three pairs of body parts had distance, relative speed, and relative acceleration features. Thus, 12 movement features were tracked in total. Each movement feature was averaged over the duration of each image acquisition frame (29.97 fps) and convolved with a model hemodynamic response function (Boynton, Engel, Glover, & Heeger, 1996) to produce a set of predictor variables. These variables were entered into linear models, together with variables coding for effects of no interest: the presence of the movies and the linear trend across the scan. The dependent measure was the preprocessed blood oxygen dependent (BOLD) signal for each participant for each ROI. Mean regression weights per participant for distance, speed, relative speed, and relative acceleration were calculated by averaging the regression weights across body parts (for speed) or pairs of body parts (for distance, relative speed, and relative acceleration). To provide significance tests with participants as a random effect, the averaged regression weights from each participant’s linear models were subjected to one-sample t tests. Only participants who showed, at minimum, unilateral localization of the ROIs were included in this analysis. Furthermore, in order to compare relationships between the motion parameters within and across the two main experimental ROIs (i.e., pSTS and hMT+), a two-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA: between-subjects variables, hMT+ and pSTS; within-subjects variables, speed, distance, relative speed, and relative acceleration) was conducted for participants who correlated at least unilaterally in both ROIs. Finally, interhemispherical differences were not considered, due to the reduced power of this test from unilateral localization in a number of participants (see Table 1). All tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction.

Whole brain

Brain activity also was analyzed at the single-voxel level across the whole brain. The raw BOLD data were preprocessed to remove artifacts due to slice timing, were corrected for participant motion, and were mapped into a standard atlas space (see Speer, Reynolds, & Zacks, 2007, and Yarkoni, Speer, Balota, McAvoy, & Zacks, [2008](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR59 "Yarkoni, T., Speer, N. K., Balota, D. A., McAvoy, M. P., & Zacks, J. M. (2008). Pictures of a thousand words: Investigating the neural mechanisms of reading with extremely rapid event-related fMRI. NeuroImage, 42, 973–987. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.258

"), for the details of the procedure). Linear models were fitted, and _t_ tests were conducted as for the ROI analysis. The results were corrected for multiple comparisons by converting the _t_ statistics to _z_ statistics, selecting a threshold of _z_ \= 3.5 and a cluster size of nine in order to control the overall map-wise false-positive rate at _p_ \= .05, on the basis of the Monte Carlo simulations of McAvoy, Ollinger, and Buckner ([2001](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR40 "McAvoy, M., Ollinger, J. M., & Buckner, R. L. (2001). Cluster size thresholds for assessment of significant activation in fMRI. NeuroImage, 13, S198.")).Results

ROI analysis

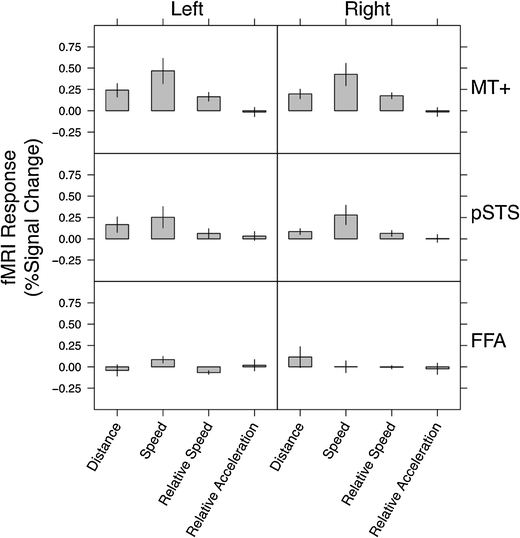

The localized ROIs were consistent with previous research on these areas: hMT+ (Beauchamp et al., 2002; Zacks et al., 2006), pSTS (Grossman & Blake, 2002; Zacks et al., 2006), and FFA (Grill-Spector, Knouf, & Kanwisher, 2004). The strengths of the relations between movement features and brain activity in hMT+, pSTS, and FFA are depicted in Fig. 3. To contain the number of multiple comparisons, and due to unilateral localization in a number of participants, statistical tests were conducted after averaging the effects across the two hemispheres. In hMT+, the distance between body parts, the speed of body parts, and their relative speed were all significantly related to brain activity [smallest t(10) = 3.58, corrected p = .02]. Relative acceleration was not [t(10) = –0.24, n.s.]. In pSTS, speed was significantly related to activity [t(10) = 2.98, corrected p = .04]. The relation for distance was significant before correcting for multiple comparisons, but it did not survive the correction [t(10) = 2.36, corrected p = .12]. Neither relative speed nor relative acceleration was significantly related [largest t(10) = 1.80, n.s.]. In FFA, no movement features were significantly related to brain activity [largest t(9) = –2.02, n.s.].

Fig. 3

Strengths of the relations between movement features and brain activity in independently identified functional regions of interest. The units are percentages of signal change per unit of distance (pixels), speed (pixels/s), relative speed (pixels/s), and relative acceleration (pixels/s2). Error bars indicate standard errors

To compare the strengths of the relationships of the motion parameters across the two main experimental ROIs (i.e., pSTS and hMT+), a two-way mixed-design ANOVA (between-subjects variables, hMT+ and pSTS; within-subjects variables, speed, distance, relative speed, and relative acceleration) was conducted using all participants for whom both regions were activated (n/ROI = 10). After Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, no significant interaction between ROI and kinematics was found, F(3, 54) = 0.3, n.s., nor did we observe a significant main effect for the ROI variable, F(1, 18) = 1.7, n.s. Finally, a significant main effect of kinematics was found, F(3, 54) = 11.24, p < .01: Post-hoc comparisons revealed a significant difference between the mean regression weights for speed being higher than those of distance, relative speed, and relative acceleration. Two similar follow-up ANOVAs comparing FFA to the two main experimental ROIs (n/ROI = 9) showed a similar pattern of results, except this time the between-subjects comparison of ROIs was significant: Activation was greater in hMT+ than in FFA [F(1, 16) = 8.0, p < .05], as was activation greater in pSTS than in FFA [F(1, 16) = 5.3, p < .05].

Finally, to understand the collinearity between the kinematic variables, we considered the correlation between each kinematic variable after it was convolved with the hemodynamic response function. A moderate positive correlation emerged between speed and distance (r = .68, p < .01), as well as weak negative correlations between relative acceleration and distance (r = –.18, p < .05) and relative acceleration and speed (r = –.16, p < .05). No other relationships were significant.

Whole-brain analysis

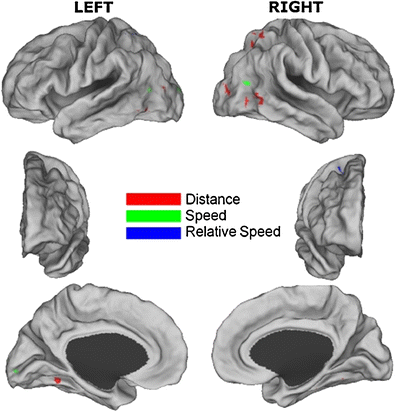

Using an analytical method similar to that in the ROI analysis, the whole-brain analysis revealed a number of regions whose neural activity was predicted by movement features in the posterior cortex, and one region each in the frontal cortex and cerebellum. These areas are listed in Table 2, and the cortical regions are depicted in Fig. 4. The distance between the head and hands of the actor was positively related to activity in a number of regions in the superior parietal cortex, to another cluster at the juncture of the parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes, and to small regions in the medial temporal lobes and the cerebellum. No regions showed activity that was negatively related to the distance between the head and hands of the actor. The speed of the same body parts was positively related to activity in a pair of temporoparietal regions situated proximally to hMT+. This was also true in an early visual area in the left lingual gyrus (likely corresponding to V2/V3) and in the left cuneus. No regions showed activity that was significantly negatively related to speed. The relative speed with which the body parts moved was positively related to activity in small clusters in the left superior parietal cortex, and in the right somatosensory cortex and premotor cortex. No regions showed activity that was negatively related to the relative speeds of the body parts, and we found no significant clusters relating to changes in relative acceleration.

Table 2 Neural regions from the whole-brain analysis that were significantly correlated with movement features

Fig. 4

Regions significantly correlated with movement features in the whole-brain analysis, with different colors/shading indicating the different variables

Discussion

When observers viewed extended natural displays of human movement, the brain activity in motion processing areas was related to the kinematics of the actor’s hands and head. This relationship was shown in both a focused ROI analysis and an unguided whole-brain analysis. The convergence of the two analytical methods highlights the association between limb movements and brain activity: Both methods showed a positive relationship between the speed of the actor’s hands and head and BOLD activity in bilateral human motion complex (hMT+). In addition, the ROI analyses highlighted relationships between hMT+ and distance, between hMT+ and relative speed, and between pSTS and speed. Speed appeared to be the main predictor of brain activity in hMT+ and pSTS, though a moderate correlation between speed and distance was found, which may have blurred individual contributions. Finally, hMT+ and pSTS showed no significant difference in terms of how their activity was modulated by motion properties, but both regions showed stronger relationships to the kinematic parameters than did FFA. In turn, FFA showed no relationships with kinematic parameters. These results indicate that motion properties, and primarily the speed of human motion, are processed in a related fashion within pSTS and hMT+, and that the FFA is not involved in biological motion processing.

Overall, the findings advance current thinking on the relationship between brain activity and kinematic properties for action understanding. Behaviorally, using the same displays as used in the present study, the kinematic parameters most strongly related to segmenting the actor’s behavior into meaningful events were the speed and distance properties of an observed agent’s limbs and head (Zacks et al., 2009). At the neural level, Zacks et al. (2006) showed that while passively viewing the activity of simple animated displays, BOLD changes in hMT+ and in pSTS were indicative of times in the displays that participants would later explicitly perceive to be the end of one event and the beginning of the next. In turn, Schubotz et al. ([2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR47 "Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

")), using natural displays and an online segmentation task, found that hMT+, in general, was related to changes in human motion, but not to goals and intents: Goal comprehension appeared to be modulated by frontal memory networks. The present results advance the theory by showing that when passively observing extended natural displays of a human actor, as opposed to elemental or animated displays, the speed and motion properties proposed as being relevant for event comprehension are correlated to changes in brain activation in the previously highlighted occipital–temporal regions (Schubotz et al., [2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR47 "Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi:

10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

"); Zacks et al., [2006](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR62 "Zacks, J. M., Swallow, K. M., Vettel, J. M., & McAvoy, M. P. (2006). Visual motion and the neural correlates of event perception. Brain Research, 1076, 150–162.")). The full comprehension of ongoing activity may lie in the combination of bottom-up processing of motion parameters and top-down action knowledge and memory (Schubotz et al., [2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR47 "Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi:

10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

")) or statistical learning of actions (Baldwin et al., [2008](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR3 "Baldwin, D., Andersson, A., Saffran, J., & Meyer, M. (2008). Segmenting dynamic human action via statistical structure. Cognition, 106, 1382–1407.")).One caveat is that the present study did not show a direct behavioral correspondence between brain activity during movie viewing and our behavioral measures of action understanding. Instead, we linked activation associated with passive viewing in the present study to behavioral measures obtained previously by Zacks and colleagues (Zacks et al., 2009) using the identical stimuli. This link is consistent with a previous work in which brain activation in occipital–temporal regions obtained via passive viewing related to the role of kinematic parameters in event segmentation (Zacks et al., 2006). In future studies, researchers may consider maintaining direct tests between behavior and brain activation, giving consideration to activation due to task demands (cf. Grosbras et al., 2012).

The neural areas highlighted by the whole-brain analysis were wholly consistent with previous findings for biological motion perception. A relationship between the speed of movement and neural activation was observed in both hMT+ and pSTS, and in the whole-brain analysis, in bilateral occipital–temporal regions. Speed correlates were also witnessed in early visual cortex (V2/V3), with acceleration correlates witnessed proximal to hMT+. The distance between body parts was related to brain activity mostly in temporal and occipital regions, with some activation in the superior parietal cortex and cerebellum. Body part distance is an indicator of posture, in that larger distances occur when the hands are spread and far from the head. These results are consistent with a distinction between the processing of form and motion (Giese & Poggio, [2003](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR20 "Giese, M. A., & Poggio, T. (2003). Neural mechanisms for the recognition of biological movements. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, 179–192. doi: 10.1038/nrn1057

"); Grosbras et al., [2012](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR25 "Grosbras, M. H., Beaton, S., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2012). Brain regions involved in human movement perception: A quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 33, 431–454."); Jastorff & Orban, [2009](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR32 "Jastorff, J., & Orban, G. A. (2009). Human functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals separation and integration of shape and motion cues in biological motion processing. Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 7315–7329. doi:

10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4870-08.2009

"); Lange & Lappe, [2006](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR38 "Lange, J., & Lappe, M. (2006). A model of biological motion perception from configural form cues. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2894–2906.")), but crossover of regions is to be expected, given the correlation between the speed and distance parameters. The correlation of speed and distance in these stimuli may mask the unique contribution of each of these parameters to brain activation. Future studies could probe these relationships using stimuli that decorrelated the two sets of features. Finally, the relationship between distance and brain activity in parietal regions likely reflects activity in body-part-centered neurons for the encoding of hand and head positions (Calvo-Merino, Glaser, Grèzes, Passingham, & Haggard, [2005](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR8 "Calvo-Merino, B., Glaser, D. E., Grèzes, J., Passingham, R. E., & Haggard, P. (2005). Action observation and acquired motor skills: An fMRI study with expert dancers. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 1243–1249. doi:

10.1093/cercor/bhi007

"); Caspers et al., [2010](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR9 "Caspers, S., Zilles, K., Laird, A. R., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2010). ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain. NeuroImage, 50, 1148–1167. doi:

10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.112

"); Colby, [1998](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR11 "Colby, C. L. (1998). Action-oriented spatial reference frames in cortex. Neuron, 20, 15–24."); Graziano & Gross, [1998](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR22 "Graziano, M. S. A., & Gross, C. G. (1998). Spatial maps for the control of movement. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 8, 195–201."); Wagner, Dal Cin, Sargent, Kelley, & Heatherton, [2011](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR56 "Wagner, D. D., Dal Cin, S., Sargent, J. D., Kelley, W. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (2011). Spontaneous action representation in smokers when watching movie characters smoke. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 894–898."); Willems & Hagoort, [2009](/article/10.3758/s13415-013-0192-4#ref-CR58 "Willems, R. M., & Hagoort, P. (2009). Hand preference influences neural correlates of action observation. Brain Research, 1269, 90–104.")).Activations in right premotor and inferior parietal regions are consistent with the existence of a fronto-parietal mirror neuron circuit (Fogassi et al., 2005; Gallese, Fadiga, Fogassi, & Rizzolatti, 1996; Rizzolatti & Sinigaglia, 2010). Similarly, activation in the right somatosensory cortex is consistent with findings of areas with mirror function in this area (Keysers, Kaas, & Gazzola, 2010). These activations were suggested to be driven by the actor being left-handed and the prominence of this hand in the video display: An influence of the left hand in these displays was previously shown on event perception (Zacks et al., 2009).

Finally, given the lack of a relationship between motion parameters and activation to the FFA, activation witnessed in the fusiform gyrus/lateral occipital cortex likely relates in part to general face perception of the actor (Kanwisher et al., 1997; Sergent et al., 1992) or to object recognition (Grill-Spector, Kourtzi, & Kanwisher, 2001) as the viewer recognizes what the actor is manipulating (Grosbras et al., 2012). For example, this may have occurred in the “Duplo” scenario, in which recognition of the object changes as the video progresses.

In conclusion, the ROI analysis showed that fMRI activity in areas associated with biological motion perception is indeed modulated by the specific kinematic properties of actors in continuous natural-motion displays. The dominant parameters appear to be the moving speeds of the hands and head of the observed actor, though a further distinction of the roles of speed and distance is required. A secondary whole-brain analysis supported these findings in hMT+ and showed the involvement of neural areas expected from previous findings for human perception. This study moves beyond mere extrapolation of a relationship between kinematics and neural activation, when observing constrained or animated displays, to firmly establishing that this relationship exists when viewing actual human motion over long durations. The monitoring of motion parameters, such as the speed and distance of limbs, by areas including hMT+ and pSTS is proposed as a key bottom-up process through which the brain processes the ongoing streams of activity that make up our environment.

References

- Albright, T. D. (1984). Direction and orientation selectivity of neurons in visual area MT of the macaque. Journal of Neurophysiology, 52, 1106–1130.

PubMed Google Scholar - Amodio, D. M., & Frith, C. D. (2006). Meeting of minds: The medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 268–277.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Baldwin, D., Andersson, A., Saffran, J., & Meyer, M. (2008). Segmenting dynamic human action via statistical structure. Cognition, 106, 1382–1407.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Baldwin, D. A., Baird, J. A., Saylor, M. M., & Clark, M. A. (2001). Infants parse dynamic action. Child Development, 72, 708–717.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Beauchamp, M. S., Lee, K. E., Haxby, J. V., & Martin, A. (2002). Parallel visual motion processing streams for manipulable objects and human movements. Neuron, 34, 149–159.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Blythe, P. W., Todd, P. M., & Miller, G. F. (1999). How motion reveals intention: Categorizing social interactions. In G. Gigerenzer, P. M. Todd, & the ABC Research Group (Eds.), Simple heuristics that make us smart (pp. 257–285). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar - Boynton, G. M., Engel, S. A., Glover, G. H., & Heeger, D. J. (1996). Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. Journal of Neuroscience, 16, 4207–4221.

PubMed Google Scholar - Calvo-Merino, B., Glaser, D. E., Grèzes, J., Passingham, R. E., & Haggard, P. (2005). Action observation and acquired motor skills: An fMRI study with expert dancers. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 1243–1249. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhi007

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Caspers, S., Zilles, K., Laird, A. R., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2010). ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain. NeuroImage, 50, 1148–1167. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.112

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Castelli, F., Happé, F., Frith, U., & Frith, C. (2000). Movement and mind: A functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. NeuroImage, 12, 314–325.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Colby, C. L. (1998). Action-oriented spatial reference frames in cortex. Neuron, 20, 15–24.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dayan, E., Casile, A., Levit-Binnun, N., Giese, M. A., Hendler, T., & Flash, T. (2007). Neural representations of kinematic laws of motion: evidence for action-perception coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 20582–20587.

Article Google Scholar - Downing, P. E., Jiang, Y. H., Shuman, M., & Kanwisher, N. (2001). A cortical area selective for visual processing of the human body. Science, 293, 2470–2473.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Downing, P. E., & Peelen, M. V. (2011). The role of occipitotemporal body-selective regions in person perception. Cognitive Neuroscience, 2, 186–203.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ferri, S., Kolster, H., Jastorff, J., & Orban, G. A. (2013). The overlap of the EBA and the MT/V5 cluster. NeuroImage, 66, 412–425.

Article Google Scholar - Fogassi, L., Ferrari, P. F., Gesierich, B., Rozzi, S., Chersi, F., & Rizzolatti, G. (2005). Parietal lobe: From action organization to intention understanding. Science, 308, 662–667.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Frith, C. D., & Frith, U. (1999). Interacting minds—A biological basis. Science, 286, 1692–1695. doi:10.1126/science.286.5445.1692

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Frith, U., & Frith, C. (2010). The social brain: Allowing humans to boldly go where no other species has been. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society B, 365, 165–176. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0160

Article Google Scholar - Gallese, V., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., & Rizzolatti, G. (1996). Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain, 119, 593–609.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Giese, M. A., & Poggio, T. (2003). Neural mechanisms for the recognition of biological movements. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, 179–192. doi:10.1038/nrn1057

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Gilaie-Dotan, S., Bentin, S., Harel, M., Rees, G., & Saygin, A. P. (2011). Normal form from biological motion despite impaired ventral stream function. Neuropsychologia, 49, 1033–1043.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Graziano, M. S. A., & Gross, C. G. (1998). Spatial maps for the control of movement. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 8, 195–201.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Grill-Spector, K., Knouf, N., & Kanwisher, N. (2004). The fusiform face area subserves face perception, not generic within-category identification. Nature Neuroscience, 7, 555–562.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Grill-Spector, K., Kourtzi, Z., & Kanwisher, N. (2001). The lateral occipital complex and its role in object recognition. Vision Research, 41, 1409–1422.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Grosbras, M. H., Beaton, S., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2012). Brain regions involved in human movement perception: A quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 33, 431–454.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Grossman, E. D., & Blake, R. (2002). Brain areas active during visual perception of biological motion. Neuron, 35, 1167–1175.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Grossman, E., Donnelly, M., Price, R., Pickens, D., Morgan, V., Neighbor, G., & Blake, R. (2000). Brain areas involved in perception of biological motion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12, 711–720. doi:10.1162/089892900562417

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hard, B. M., Recchia, G., & Tversky, B. (2011). The shape of action. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 140, 586–604.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Heider, F., & Simmel, M. (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. The American Journal of Psychology, 57, 243–259.

Article Google Scholar - Huk, A. C., & Heeger, D. J. (2002). Pattern-motion responses in human visual cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 5, 72–75.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Iacoboni, M., & Dapretto, M. (2006). The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7, 942–951. doi:10.1038/nrn2024

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Jastorff, J., & Orban, G. A. (2009). Human functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals separation and integration of shape and motion cues in biological motion processing. Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 7315–7329. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4870-08.2009

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Johnson, K. L., McKay, L. S., & Pollick, F. E. (2011). He throws like a girl (but only when he’s sad): Emotion affects sex-decoding of biological motion displays. Cognition, 119, 265–280.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Jola, C., McAleer, P., Grosbras, M., Love, S. A., Morison, G., & Pollick, F. E. (2013). Uni- and multisensory brain areas are synchronized across spectators when watching unedited dance recordings. Perception, 4, 1–20.

Article Google Scholar - Kanwisher, N., McDermott, J., & Chun, M. M. (1997). The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. Journal of Neuroscience, 17, 4302–4311.

PubMed Google Scholar - Keysers, C., Kaas, J. H., & Gazzola, V. (2010). Somatosensation in social perception. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 417–428.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kozlowski, L. T., & Cutting, J. E. (1977). Recognizing sex of a walker from a dynamic point-light display. Perception & Psychophysics, 21, 575–580. doi:10.3758/BF03198740

Article Google Scholar - Lange, J., & Lappe, M. (2006). A model of biological motion perception from configural form cues. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 2894–2906.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Mather, G., & Murdoch, L. (1994). Gender discrimination in biological motion displays based on dynamic cues. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 258, 273–279.

Article Google Scholar - McAvoy, M., Ollinger, J. M., & Buckner, R. L. (2001). Cluster size thresholds for assessment of significant activation in fMRI. NeuroImage, 13, S198.

Article Google Scholar - McCarthy, G., Puce, A., Gore, J., & Allison, T. (1997). Face-specific processing in the human fusiform gyrus. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 9, 605–610.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Newtson, D. (1976). Foundations of attribution: The perception of ongoing behavior. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. F. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (pp. 223–248). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Google Scholar - Peelen, M. V., & Downing, P. E. (2005). Selectivity for the human body in the fusiform gyrus. Journal of Neurophysiology, 93, 603–608.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pollick, F. E., Kay, J. W., Heim, K., & Stringer, R. (2005). Gender recognition from point-light walkers. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 31, 1247–1265.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pollick, F. E., Paterson, H. M., Bruderlin, A., & Sanford, A. J. (2001). Perceiving affect from arm movement. Cognition, 82, B51–B61.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Rizzolatti, G., & Sinigaglia, C. (2010). The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: Interpretations and misinterpretations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 264–274.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Schubotz, R. I., Korb, F. M., Schiffer, A. M., Stadler, W., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2012). The fraction of an action is more than a movement: Neural signatures of event segmentaiton in fMRI. NeuroImage, 61, 1195–1205. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.008

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Sergent, J., Ohta, S., & MacDonald, B. (1992). Functional neuroanatomy of face and object processing: A positron emission tomography study. Brain, 1, 15–36.

Article Google Scholar - Speer, N. K., Reynolds, J. R., & Zacks, J. M. (2007). Human brain activity time-locked to narrative event boundaries. Psychological Science, 18, 449–455.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Swallow, K. M., Braver, T. S., Snyder, A. Z., Speer, N. K., & Zacks, J. M. (2003). Reliability of functional localization using fMRI. NeuroImage, 20, 1561–1577.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Talairach, J., & Tournoux, P. (1988). Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system—An approach to cerebral imaging. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme.

Google Scholar - Tootell, R. B. H., Reppas, J. B., Kwong, K. K., Malach, R., Born, R. T., Brady, T. J., & Belliveau, J. W. (1995). Functional analysis of human MT and related cortical areas using magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience, 15, 3215–3230.

PubMed Google Scholar - Troje, N. F. (2002). Decomposing biological motion: A framework for analysis and synthesis of human gait patterns. Journal of Vision, 2(5), 371–387. doi:10.1167/2.5.2

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Van Overwalle, F., & Baetens, K. (2009). Understanding others’ actions and goals by mirror and mentalizing systems: A meta-analysis. NeuroImage, 48, 564–584.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Vizioli, L., Smith, F., Muckli, L., & Caldara, R. (2010, June). Face encoding representations are shaped by race. Paper presented at the 16th Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping, Barcelona, Spain.

- Wagner, D. D., Dal Cin, S., Sargent, J. D., Kelley, W. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (2011). Spontaneous action representation in smokers when watching movie characters smoke. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 894–898.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Weiner, K. S., & Grill-Spector, K. (2011). Not one extrastriate body area: Using anatomical landmarks, hMT+, and visual field maps to parcellate limb-selective activations in human lateral occipitotemporal cortex. NeuroImage, 56, 2183–2199.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Willems, R. M., & Hagoort, P. (2009). Hand preference influences neural correlates of action observation. Brain Research, 1269, 90–104.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yarkoni, T., Speer, N. K., Balota, D. A., McAvoy, M. P., & Zacks, J. M. (2008). Pictures of a thousand words: Investigating the neural mechanisms of reading with extremely rapid event-related fMRI. NeuroImage, 42, 973–987. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.258

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar - Zacks, J. M. (2004). Using movement and intentions to understand simple events. Cognitive Science, 28, 979–1008.

Article Google Scholar - Zacks, J. M., Kumar, S., Abrams, R. A., & Mehta, R. (2009). Using movement and intentions to understand human activity. Cognition, 112, 201–216.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zacks, J. M., Swallow, K. M., Vettel, J. M., & McAvoy, M. P. (2006). Visual motion and the neural correlates of event perception. Brain Research, 1076, 150–162.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zacks, J. M., Tversky, B., & Iyer, G. (2001). Perceiving, remembering, and communicating structure in events. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 130, 29–58. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.130.1.29

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zeki, S. M. (1974). Functional organization of a visual area in the posterior bank of the superior temporal sulcus of the rhesus monkey. The Journal of Physiology, 236, 549–573.

PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar