Hyperallergic Reviews Nineteen – Drawn & Quarterly (original) (raw)

“I don’t even know who the weirdo is — me or everyone else.” These words, spoken by one of the characters in Ancco’s latest comic Nineteen, evince the messy, hesitant ways in which teenagers configure their universes. Ancco, the pen name of Choi Kyung-jin, gained fame in South Korea through her short diary-like webcomics, which she began publishing in 2002. Unlike those quotidian tales, however, the stories in Nineteen are balanced on the knife-edge of memoir and fiction, rippling through domestic violence, social oppression, and rebellion.

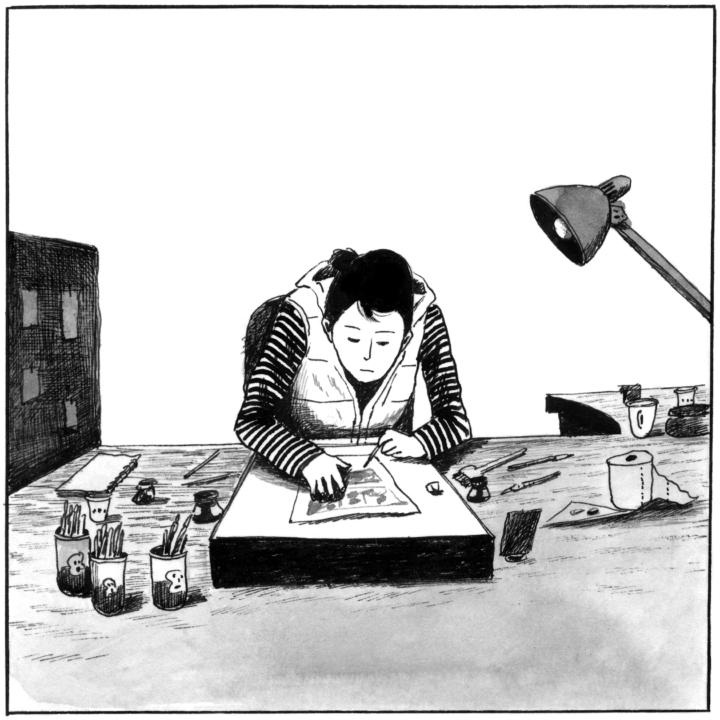

Written over a period of five years, these grayscale stories evoke the murkiness of adolescence. In each chapter, Ancco’s young characters struggle in the transition between puberty and adulthood, oscillating between emotional and rational responses to their environment. For example, in “nineteen,” Choi (based on Ancco herself) drinks, smokes, and draws profane comics at school, actions that lead to severe consequences: in one scene, her father beats her raw with a badminton racket. But although Choi attempts to clean up and study, she falls back into the same destructive, abusive patterns, perhaps too young to understand that these cycles are tied to larger institutional problems in South Korea, such as patrilineal family structures, substance abuse, gender-based violence, and economic inequality.

Although Ancco introduces some levity — in the form of a botched haircut or anthropomorphic dogs — she returns frequently to these social issues, as if to demonstrate the insidiousness of their existence. In the story “life,” she references high teen suicide rates through the eyes of a queer, HIV-positive character; and in “do you know jinsil?,” we see patriarchy’s trickle-down effect on interpersonal female relationships. In the latter, Choi initially expresses concern to her friends about Jinsil’s alleged rape and abuse. But when Jinsil appears, Choi treats her with disgust, perhaps because she is the type of woman — poor, abused, socially outcast — that young girls are told to fear, lest they become her. In this moment of devastating lucidity, we see a single panel filled with Jinsil’s face, which appears blank and distant — expecting, perhaps, the hollow empathy. Ancco is especially skilled in narrating such complexities through obvious cues — text and facial expression — and subtle details. For example, a shadowed highway in “nineteen” becomes a dual space, its redacted tarmac a potential for trauma as well as safety. (This same highway is also a significant landmark in her award-winning graphic novel, Bad Friends.)

If the teenagers in Nineteen map the malaise of a contemporary society, it is the older generations which carry its traumas. A significant character is based on Ancco’s grandmother, who passed away as the English version of the book — flawlessly translated by Janet Hong — was being put together. In “grandma,” the matriarch recalls that when she was “a wee thing, foreign men would come and kidnap young girls”; and “wild roses” reveals the specific loneliness of an entire generation of war survivors through solitary gardening scenes. Choi appears in these stories, often kind but not always — in “wild roses,” she only shows up to pick up necessities, leaving her grandmother to eat alone in the dark. There is a rawness to Ancco’s depictions of this generation gap, and a rare willingness to admit imperfections in how teens handle the world and themselves.

Korea’s youth has had to contend with the country’s war traumas and the ongoing oppression of marginalized communities. In Nineteen, however, Ancco hints that it is only through confronting these issues — however painful — that these young adults can also contend with their own voices, in the process sketching out who they are, and what they want to say.