The animated chop of meat (and other miraculous marvels): pilgrimage songs in the Cantigas de Santa Maria (CSM article 4/6) (original) (raw)

Left: A miraculous flying chair illustrating Cantiga 153.

Right: A miraculous chop of meat is hung at Mary’s altar in a miniature decorating Cantiga 159.

What do an animated chop of meat, a man who wouldn’t hang, a talking sheep, a flying chair, a life-saving chemise, and a shoe that heals by being rubbed on the face have in common? They all appear in the pilgrimage songs of the 13th century Iberian songbook, Cantigas de Santa Maria (Songs of Holy Mary). This is one of the most important collections of medieval music, and certainly one of the largest, with 420 songs, illustrated with vibrant illuminations of the songs and court musicians.

In these songs there are constant references to pilgrimage, reflecting its importance in medieval Christianity generally. Pilgrimage represents the utter dependence of believers on divine favour for their physical health, their emotional dependence on divine approval, and their dependence on heaven’s judgement for their eternal fate. Holy relics, which proliferated in the period prior to the Cantigas, play a talisman-like role and bring all three themes together.

This article, the fourth in a series of six about the Cantigas, explores the many pilgrimage themes in the Cantigas, beginning with a live performance of Cantiga 159, featuring an animated pork chop.

Click picture to play the video .

A live performance of Cantiga 159: The pilgrims and the stolen chop, arranged and

sung in English by Ian Pittaway. The original Galician lyric does not specify what type

of meat or chop is being referred to. Ian made it a pork chop because, in reconstructing

the original Galician syllable count and rhyme scheme in English, making it so helps

the rhythm and rhyme to flow, and brings out the humour of the song.

The purpose of pilgrimage

Pilgrimage is a physical journey at home or abroad to a holy destination associated with a saint, but spiritually and psychologically it signifies so much more. In the middle ages, pilgrimage was a sign of the need for physical healing when the world gives no hope, forcing reliance on supernatural intervention at the shrine of a saint. The journey was taken as penance for sins, in many cases acting on an indulgence, a clerical instruction to act as part of a plea-bargain to reduce time being punished in purgatory. Pilgrimage was a way of giving thanks for divine activity. It activated a kind of supernatural insurance policy against ill fortune. For Alfonso X, King of Castile, León and Galicia, chief author of the Cantigas, creating a site of pilgrimage was a way of gaining power and prestige. All of these themes are explored below in relation to the Cantigas, within the context of wider medieval sources.

By the 4th century, the Church recognised pilgrimage as a valid religious expression, endorsing and promoting it as a way of escaping worldly affairs and focussing on faith. The earliest Christian pilgrimages centred around Jerusalem, Palestine and the Roman Empire, since this region was the location of the life of Christ and the earliest saints such as Peter, Paul and Stephen, as recorded in the New Testament. The impact of being on the exact spot (as was claimed) where holy persons enacted holy events is recorded by Saint Jerome (347–420), writing of Saint Paula of Rome (347–404): “Here, when she looked upon the inn made sacred by the virgin and the stall where the ox knew his owner and the ass his master’s crib … she protested in my hearing that she could behold with the eyes of faith the infant Lord wrapped in swaddling clothes and crying in the manger, the wise men worshipping him, the star shining overhead, the virgin mother, the attentive foster-father, the shepherds coming by night to see the word that had come to pass”.

On the left is a pilgrim from the Luttrell Psalter,

England, c. 1325–35 (BL Add MS 42130).

We can see from the shell-shaped badge in his

hat that he has journeyed to Santiago de

Compostela, the shrine of Saint James. Often

the features we see here signified that the figure

was Saint James himself, as we see on the right

– only the addition of the halo signifies the

difference between pilgrim and saint – from

Les Grandes chroniques de France, France,

1332–1350 (BL Royal MS 16 G VI). The

detail of bare feet in both images here is

not universal in depictions of pilgrims,

and signifies penance.

(As with all pictures, click to see

larger in a new window.)

As Christianity expanded geographically, so did saints and therefore pilgrimage centres numerically. Places of pilgrimage proliferated to the point where any church could take this role, since relics, items imbued with holy power through association with a saint, were located in every church from the 8th century by universal decree. This did not make every church of equal value to the pilgrim: the major pilgrimage sites retained their pre-eminence – Rome for Christ, Mary, Peter and Paul; Jerusalem for Christ, Mary and Abraham; Santiago de Compostela for Saint James; Cologne Cathedral for the shrine of the Three Kings, the tomb of the three magi; and Canterbury Cathedral for Thomas Becket.

Before making the journey, pilgrims received a blessing from the local bishop and, if the pilgrimage was penance, they made a full confession. Though it is clear that not all pilgrims wore it, there was special pilgrims’ clothing: a broad-brimmed hat, a long and coarse garment, a sturdy staff and a small purse. Upon reaching the holy place, a badge specific to the site could be bought and worn to demonstrate pilgrimage piety.

The journey itself was integral to the experience, requiring a great deal of effort, money and commitment. A long absence was required, possibly a year or more, with the necessary loss of earnings coupled with the expense of food, transport, lodging, often in monasteries en route, and offerings to the destination shrine and any other shrines on the way. As well as the obvious potential peril of exhaustion and falling ill, the journey involved other significant dangers as described in the Cantigas: shipwreck (CSM 33) and/or drowning (CSM 171, CSM 383), getting lost in unfamiliar and perilous territory (CSM 49), robbery (CSM 57, CSM 302), trickery and false accusations against the pilgrim stranger (CSM 175), arguments and fights between pilgrims (CSM 198), and life-threatening weather (CSM 311).

Pilgrimage was an inner, spiritual journey as much as an outer, physical expedition. Purity of purpose, the contrite and obedient heart, was the central principle. Thus, for the medieval pilgrim, there were inner perils, too, as shown in a stone carving, dated c. 1330-40, in Beverley Minster, East Riding of Yorkshire, home to the tomb of Saint John of Beverley, a pilgrimage destination from the 11th century. Below we see a pilgrim, identifiable by his distinctive broad-brimmed hat, struggling in the grip of a long-eared, two-headed monster. Its largest head is shown on the underside, with protruding fangs and spots of dark red paint, the last traces of the colours that once completed its appearance. On each side of this largest head, its clawed feet face forward. The smaller head on its tail is biting onto one of its own wings to further strengthen its grip on the helpless man. The man’s mouth shows his physical strain, his eyes show his fear. His left foot is on the back of the monster’s head, his right foot on the back of its neck in a vain attempt to escape, his hands helpless to do anything but hold on to the beast. This is the amphisbaena (anphivena or other variants) of Greek mythology. Amphisbaena comes from the Greek for ‘walk both ways’ and it is “so called”, says the 13th century Bodley 764 bestiary, “because it has two heads, one in the right place, the other on its tail. It goes in the direction of both heads, and its body forms a circle.” Carvings from the 12th century onward and later writings make clear that this beast represents the hypocrite Satan who faces both ways; thus the carving symbolises the pilgrim, outwardly pious with his pilgrim’s hat, inescapably ensnared by his hypocrisy: the Beverley pilgrim has strayed from the true path, his pilgrimage of no avail since his heart is sinful, his piety without sincerity.

Four views of the pilgrim ensnared by the amphisbaena, symbolising him trapped by his

Satanic hypocrisy. Stone carving in Beverley Minster, East Riding of Yorkshire, c. 1330-40.

Photographs © Ian Pittaway.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in new window.)

Pilgrimage themes in the Cantigas

The raw material Alfonso X and his courtiers worked with, the collections of Marian miracle stories circulating in 13th century Europe, were vibrant, vivid and populated by people of many classes and predicaments. Though pilgrimage was clearly a serious business, in versifying these stories and setting them in song they were remoulding them in an art form meant to entertain. Among the pilgrimage songs in Alfonso’s manuscripts, the following themes emerge: (a) pilgrimage as a supernatural insurance policy against ill fortune; (b) to give thanks for the Virgin’s intervention; (c) as penance for sins; (d) for a healing miracle; (e) travelling on behalf of someone ill or dead.

(a) The dedication of some pilgrims activates a kind of supernatural insurance policy against ill fortune, paid for by sincere holy devotion.

For example, in CSM 33, a storm at sea tore the rigging of a ship full of pilgrims. A pilgrim who fell overboard miraculously survived because “Holy Mary saved me … in order to show you that he who believes in her will be saved by her wisdom.”

In CSM 26, a man who made an annual pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela almost invalidated his heavenly insurance: he sinned one year on the night before he travelled, spending “the night with a dishonest woman to whom he was not married.” The devil appeared to him in the form of Saint James, commanding him to enact penance by cutting “off that member of yours which caused you to fall into the devil’s power, then cut your throat.” When he did so, Saint James himself appeared and argued with the devil for his soul, referring it to the Virgin who judged that “the dead pilgrim [be] revived in fulfilment of God’s will. However, he never recovered the missing part with which he had sinned.”

In CSM 146, a man went on pilgrimage to the shrine of Holy Mary of Albesa against his mother’s advice, who feared for his safety. On the way, his enemies gouged out his eyes and cut off his hands. The maimed man begged passing pilgrims to take him to Albesa, since he had no doubt the Virgin would heal him. His mother heard the news, rushed to Albesa and prayed for her son, whereon “the holy empress, mother of God Emmanuel, at once made for that young man small beautiful eyes like a partridge, and his hands grew out again from the wrists.”

Two illuminations accompanying Cantiga 146.

Left: The maimed pilgrim is helped to Albesa by two other pilgrims.

Right: At the altar of Albesa his mother prays for him and the

Virgin restores his hands and gives him new eyes.

In CSM 175, a German father and son on the way to Santiago de Compostela stayed partway at an inn in Toulouse, run by a heretic, who planted a silver cup in the son’s sack and accused him of theft. As a result, the magistrate ordered the son’s arrest, and he was charged and hanged. The grieving father continued to Santiago and returned to Toulouse to visit the site of his son’s death. His son was still hanging on the gallows, and he spoke: “Good man, father, do not kill yourself, for I am surely alive. The Holy Virgin who sits on the throne with God keeps me. She held me in her hands in her infinite love.” The father ran to find witnesses, who took his son down from the gallows. The son told how he was framed, and the crowd found the heretic and “put him to a frightful death in a fire”.

In CSM 198, a large group of male pilgrims at Terena were celebrating, and it turned into a murderous fight because “the sly devil so aroused their anger”. They were “wounding each other violently, and this unfortunate fray lasted most of the night as they tried to kill each other. However, the pure and noble Virgin, whose pilgrims they were, did not permit them to go home from the battle dead nor even so much as wounded. Instead, in the middle of a field where they had fought since nightfall, struggling to the death, she caused them suddenly to become very friendly and pleased with each other.”

(b) Others went on pilgrimage to give thanks for the Virgin’s intervention: being saved from being trapped under frozen ice in a river (CSM 243); cured of rabies (CSM 275); remaining unharmed when attacked by a lance and a javelin (CSM 22); having an arrow go through the eye and lodge in the neck, the removal of the arrow effecting both a cure and improved eyesight (CSM 129). In CSM 147, “a poor woman bought a sheep with all the money she could scrape together and gave it right away to a shepherd” for him to shear, so that she could “claim the wool from him and sell it for her profit.” When the shepherd lied that the sheep had been eaten by a wolf, she prayed to the Virgin and “the hapless sheep cried: “He-e-ere I-I-I a-a-am.” Thus Holy Mary exposed the deceit.” She sheared her sheep and, in thanks to Mary, carried the wool to the pilgrimage site of Rocamadour.

Two illuminations accompanying Cantiga 147.

Left: A poor woman has bought a sheep and given it to a shepherd to sheer.

Right: When the shepherd lied that her sheep had been taken by wolves,

her sheep talks to reveal her presence.

(c) Those who confessed grave sins could go on pilgrimage as penance. In The Deeds of Kings, c. 1210, Gervase of Canterbury describes the return of King Henry II to England from Normandy in 1174 after the Great Revolt. Henry considered the rebellion to be divine punishment upon him: “he set out with a sad heart to the tomb of Saint Thomas at Canterbury … he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr’s tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury.” There are several stories in the Cantigas of pilgrimage as penance (acting for the remission of sins) and penitence (being sincerely sorry and seeking forgiveness). In CSM 117, a seamstress who worked on the Sabbath was punished by God by having her hands twisted. When she repented at the altar at Chartres, her hands were cured by Mary. In CSM 163, a gambler who lost everything “renounced the Virgin and refused to fear her”. He was “crippled in his body because of the great blasphemy he had uttered” and “lost his speech, for God had contempt for him”. He indicated with signs that he wished to go to Salas. When he repented there at Mary’s altar he was cured by the Virgin. In CSM 153, “a woman of Gascony … scorned the pilgrimage of Holy Mary of Rocamadour” and “said that she would never go there unless a chair upon which she was sitting carried her there.” This is precisely what happened, whereupon “the woman guiltily prostrated herself, calling herself miserable”.

(d) Healing miracles, the need for physical recovery when the world gives no hope of cure, abound in the Cantigas, particularly at Mary’s shrine at Salas in the province of Huesca, northern Aragón, modern-day Spain. In CSM 166, a man who had twisted limbs for five years is cured there when he takes an offering of wax: “He went along nimbly as one who feels no pain, notwithstanding that his feet had been unaccustomed to walking for a long time.” In CSM 167, the same offering at the same shrine revives the dead child of a Moorish woman. “She at once became a Christian, for she saw that Holy Mary had given him back to her alive”. In CSM 168, a woman lost all her children in succession: “She grieved so deeply for the last one who died that she almost went mad.” She took her dead son to Salas “and the worthy queen resuscitated him and made him come to life in her arms.” In CSM 173, a man “had such a painful attack of kidney stones that he was in mortal agony … he could not even eat nor sleep nor do anything except call constantly on the Virgin, lady of mercy.” He went on pilgrimage to Salas, prayed to the Virgin “who holds the world in her command” and asked her to forgive his sins. “He woke up then and found the whole kidney stone in the bed with him. It was truly as large as a chestnut, you may be sure.” (You can see a performance in English of this Cantiga, The blessings of Maria ~ or ~ The kidney stone Cantiga, by clicking here.)

(e) People of great wealth sometimes paid for others to go on a pilgrimage on their behalf. In 1352, a London merchant paid a man £20 to go on a pilgrimage to Mount Sinai for him. Similarly, if the person was too ill to make the journey, it was possible to effect a cure by a sponsor making the journey on their behalf. The Paston family were Norfolk gentry whose letters of 1422-1509 have survived. Part of a letter written by Margaret Paston to her husband in 1484 says, “When I heard you were ill I decided to go on pilgrimage to Walsingham … for you.” We see this in CSM 197, where “a rich and peaceable man …. had a son whom he loved above all else.” When the son, who suffered from seizures up to seven times a day, died because the devil “seized him so fiercely that he strangled him there where he stood”, his brother went on pilgrimage to Terena, as the dead man had intended to do, so that his sins may be forgiven on his behalf. The brother travelled, prayed to the Virgin, whose pleas God heard, and the dead man revived, never to suffer from seizures again.

Pilgrimage as prestige: Alfonso’s Holy Port

The final quarter of the collection of 420 Cantigas includes many testaments to King Alfonso’s establishment of a new pilgrimage shrine, a body of 20 songs concerning one important city. When north African Moors invaded southern Iberia in 711, they named the municipality under discussion Alcante or Alcanatif, Port of Salt. When Alfonso X recaptured it in 1260, he renamed it Santa María del Puerto, Holy Mary of the Port.

CSM 328 is specifically about its establishment and the Virgin’s part in the process, and CSM 327 describes its colonisation and the protection given it by Mary. So keen was Alfonso to establish a Christian population in and trade to the newly-won city that he “gladly gave rich merchants all they asked, providing they would come there to settle”, and that included Moors, members of the very group he had just deposed. CSM 398 describes Alfonso establishing it as a new centre of pilgrimage: “There King don Alfonso of León and Castile had a noble and beautiful church built which he gave to Holy Mary as house and chapel in which her name might be praised by many people. While they were building it, Holy Mary performed very beautiful miracles there, delightful to hear, for those who are desirous of her mercy.”

Castillo San Marcos, shown above and below, is the fortified church commissioned by Alfonso X

for the praise of the Virgin Mary in Santa María del Puerto (now El Puerto de Santa María). It acted

as a church, a place of pilgrimage, and a Christian fortress during the Christian Reconquest of Iberia.

Built upon the remains of a Moorish mosque, the wall of the qibla, signifying the direction of Mecca

(or Makkah), still survives. The castle was enlarged during the 14th and 15th centuries, and its crenels

and towers restored in the mid 20th century. It is located in the city centre, at Plaza Alfonso X, with

a bust of the king outside the castle walls. Used today for cultural events, conferences, and dining,

it is one of the most visited monuments in El Puerto de Santa María. (Castillo San Marcos is not

to be confused with the Castillo de San Marcos fort in the USA.)

Of the 20 Cantigas about Holy Mary of the Port, one is about its establishment and one about its colonisation, three are miracle stories about Mary aiding her church’s construction and protecting its workers, twelve are miracles at Mary’s newly-established shrine, and three are other miracles by Holy Mary of the Port.

Of the 20 Cantigas about Holy Mary of the Port, one is about its establishment and one about its colonisation, three are miracle stories about Mary aiding her church’s construction and protecting its workers, twelve are miracles at Mary’s newly-established shrine, and three are other miracles by Holy Mary of the Port.

Songs about miracles at the new shrine are the most numerous for an obvious reason: without miracles the shrine had no supernatural credibility and no reason for pilgrims to come. CSM 367 concerns the king himself, how “Holy Mary of the Port cured King don Alfonso from a great sickness which caused his legs to swell so much that they would not fit inside his shoes … This miracle happened … when he went to see the beautiful church he had built in Andalusia.” Other miracles at the new royally-established shrine include the cure by Holy Mary of the Port of “a woman with twisted mouth and limbs who had come to her house on a pilgrimage” (CSM 357), rabies (CSM 372 and CSM 393), a woman who had “a snake … in her belly for three years” (CSM 368), and straightening “the crippled limbs of a girl whom they brought there on pilgrimage” (CSM 391), among others.

For a king who had staked his identity on being Virgin Mary’s troubadour, her religious and political champion, composing songs in her praise, contender for the Catholic title of Emperor of the Romans (which he did not gain – see the second article in this series by clicking here), the recapture and religious renaming of Alcante and its establishment as a Marian shrine was a significant victory of recognition, power and prestige. Alfonso’s three actions – recapture, populate, establish a pilgrimage shrine – are the three foundations by which he attempted to secure its longevity. It remains to this day in the province of Cádiz, Andalusia.

The power of the relic

Central to medieval pilgrimage was the power of holy relics, physical objects associated with saints which have the heavenly authority to effect cures. Since illness and poor fortune were associated with sinfulness, cure at a shrine was a sign of divine forgiveness. Relics therefore acted as a bridge between heaven with Earth, between the eternal and temporal, connecting saints with sinners, the miraculous with the mundane.

In 1346, Saint-Omer Church in France listed some of the relics it held: “A piece of Our Lord’s Cross … Pieces of the Lord’s tomb … A piece of the Lord’s cradle … Some of the hairs of St. Mary. A piece of her robe … Part of St. Thomas of Canterbury’s tunic. Part of his chair. Shavings from the top of his head. Part of the blanket that covered him, and part of his woollen shirt … part of his hair shirt. Some of his blood.”

Implied in this list are many important ideas for understanding the medieval Christian worldview, and therefore for understanding the pilgrim songs of the Cantigas, which will now be addressed: how relics were categorised; collected; kept; understood; distributed; and their encapsulation of the universal in the local.

Relic categories: Mary’s miraculous shift

The silk shift allegedly worn by Mary while giving birth to Jesus, now in Chartres Cathedral, France.

Relics fall into two broad categories, those associated with the Bible – people and events in the life of Christ, his disciples, his mother, the Hebrew prophets – and those associated with saints and martyrs in post-biblical Christian history. Of all the saints in the Catholic panoply of praise, God’s Mother was preeminent from the 12th century onwards. Though Marian shrines were ubiquitous, Marian relics were rare. The reason was theological. Catholic belief in Mary’s bodily assumption into heaven is widely and regularly attested from the 5th century on, celebrated by Pope Sergius I in the 8th century, with the Feast of the Assumption declared official by Pope Leo IV in the 9th century. This meant no one could lay claim to the mandible of Mary, the ventricles of the Virgin or the hipbone of the Heavenly Queen. With no corporeal remnants of the Virgin, shrines claimed Marian items of clothing as relics.

The sancta camisia or sainte chemise, a silk shift or chemise supposedly worn by Mary when giving birth to Jesus, was acquired by Byzantine Empress Irene of Constantinople, who sent it as a gift to Charlemagne (Charles the Great), whose grandson Charles the Bald gifted it to Chartres Cathedral, France, in 876. Since this item had allegedly been in physical contact with Mary, and it had thereby been infused with holy power, stories circulated of knights’ tunics coming into contact with it and gaining miraculous protection in battle. Though Chartres Cathedral didn’t gain the fame of the major medieval pilgrimage sites, it did become the chief shrine of Île-de-France (Paris and its region).

The idea that miraculous events follow merely by touching a garment worn by a holy person is present in the Bible. A woman in Mark’s Gospel 5: 25-34 had been failed by doctors and “had been bleeding for twelve years”, but was cured by reaching out to Jesus and touching his clothes: “As soon as she touched them, her bleeding stopped, and she knew she was well.” The notion that such holy potency could extend to Mary is a post-biblical idea, but it is certainly present in the 13th century Iberian Cantigas de Santa Maria, relating directly back to the 9th century acquisition of Mary’s shift in Chartres. CSM 148 tells the story of “a chest” in Chartres “in which is kept a linen shift which belonged to [Mary], and many go to see it. Each one takes his cloth and lays it on that shift, which lies wrapped in gauze. They then make shifts, each to his own measure, which they wear in battle, so that God will protect them … One day [a knight] was riding next to a thicket, wearing his shift, for he had not time to put on his armour. Then his enemies sprang out in front of him and dealt him savage, mortal blows … but the Virgin protected him so that not a single blow reached his body nor did they make any mark.”

An illustration panel for CSM 148, which reads, “A knight, wearing such a garment

[a newly-made shift which has been in contact with Mary’s shift], was attacked by his

enemies. Although they tried to pierce him with lances, they were unable to wound him.”

Aachen Cathedral, Germany, also claimed to have a shift worn by Mary, along with the swaddling clothes of the infant Jesus, a belt worn by him, his crucifixion loincloth, and the cloth that held the decapitated head of John the Baptist. Pilgrimage to Aachen is attested from 1238. By the 14th century, pilgrims came in such numbers that being able to see or touch the relics was impossible for most, so from 1322 the relics were displayed outside on a tower. Since this meant that pilgrims could not touch the relics, pilgrim badges (see below) were designed to hold a mirror, which could be aimed at the relics to catch their reflection and thereby receive their holy power from a distance. This holy potency could then be redirected to other objects from the mirror, for example by aiming it at bread eaten by a sick pilgrim in the hope of a cure. This once-removed experience did nothing to deter numbers. In 1337, the Queen of Hungary made the pilgrimage with an escort of 700 knights. Since 1349 there has been a tradition of displaying the relics only once every 7 years for 15 days, from the 10th to the 24th of July. (This continues to this day, the last occasion, at the time of writing, being 2014.) In 1433, the mystic Margery Kempe made her pilgrimage from Norfolk, England, to see the Virgin’s smock. During the 15 day relic display of 1496, the gatekeepers of Aachen counted 147,000 pilgrims.

Left: The shift claimed to have been worn by the Virgin Mary, held up by clergy in Aachen Cathedral.

Right: A 15th century pilgrim badge from the shrine of Our Lady of Aachen, Germany, made of

lead alloy, 3cm x 3cm, representing Mary’s shift. Badges were often made of two or more frames,

designed to hold a mirror that could be aimed at relics to receive their holy potency. The section

shown would have been one of three frames of the Aachen badge.

The making of relics: Thomas Becket’s blood, the miraculous chop of meat, and the miraculously clean chasuble

Relics have a highly personal quality, being body parts such as hair, bone, a finger, a piece of Jesus’ cradle or a part of the cross. Taking the claim of authenticity at face value it follows that, upon the holy person’s death, no time can have been wasted in gaining the relic. In c. 1175, Benedict of Peterborough (Benedictus Abbas) wrote in his Chronicle that 5 years earlier, after the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral, Thomas’ spilt blood was collected and poured into a clean vessel to be kept in the church. In the Trinity Chapel of Canterbury Cathedral are a series of stained glass panels, made c.1185–1220, depicting the life, martyrdom and sainthood of Thomas. The images include several miracle cures through the ‘water of Saint Thomas’, the mixing by monks of a drop of Becket’s blood with water for sick pilgrims to drink or bathe affected limbs. Among these depictions is the cure of leper Richard Sunieve; the cure of a woman named Etheldreda from malarial fever; Petronilla, an epileptic nun from Polesworth, who sits at Thomas’ tomb, having her feet washed with Becket’s diluted blood; and Juliana Puintel, with stomach pains after eating fish, cured after sleeping at the shrine. Other pilgrims took the blood/water away in a container known as an ampulla (plural ampullae), a flask of glass, ceramics or metal used for carrying holy liquids such as water, oil or blood, many of which have survived from Canterbury.

Stained glass window in Canterbury Cathedral, made in c.1185–1220, showing the cure of

leper Richard Sunieve with the ‘water of Saint Thomas’, a drop of Thomas Becket’s blood

in water, administered by a monk. Richard is usually interpreted as being the figure in red,

so overcome with gratitude that he throws himself on Becket’s tomb. However, the figure

in red is reaching down toward a niche in the side of the saint’s tomb, a design on saints’

tombs which allowed the pilgrim to make contact with the saint by placing inside the part

of the body in need of healing. Richard Sunieve must therefore be the figure in white,

receiving Becket’s blood from the monk.

(Crown Copyright. Historic England Archive.)

Both sides of a lead alloy ampulla for the ‘water of Saint Thomas’, measuring 63.67mm high by

54.4mm wide, late middle ages, now in the British Museum. On the left is God the Father embracing

the soul of Thomas Becket, with an angel on both sides. On the right is the martyrdom of Becket.

Two of the Cantigas may describe the making of a relic.

Cantiga 159 is the song performed in English at the beginning of this article, and is Alfonso’s versification of a story from a collection of 126 stories written by the monks of Rocamadour, France, in 1172-73, about the miracles performed there for the pilgrims who came from Iberia, Italy, Germany and England, as well as from the home country. A group of nine pilgrims took “lodging and ordered meat, bread, and wine … for their supper”. After praying to Mary they were very hungry, and eagerly opened the pot of chops, expecting nine but finding eight, “for the servant girl had robbed them, and they were very annoyed about it.” After searching the house and failing to find the chop, they prayed to Mary to reveal it. She did so by causing the chop to jump from side to side inside the chest in which it was hidden, banging on the sides. They opened the chest and were so delighted to find it that they didn’t eat it; instead “they took the chop and hung it by a silken cord before her holy altar, praising holy Mary, who performs beautiful miracles.” Certainly, the chop is a souvenir of the miracle, but does it then act as a relic? The song ends with the hanging of the chop at the altar and the praise of Mary, so we’re not told if the chop, like Mary’s shift, has supernatural properties of healing and protection through being touched by her heavenly powers.

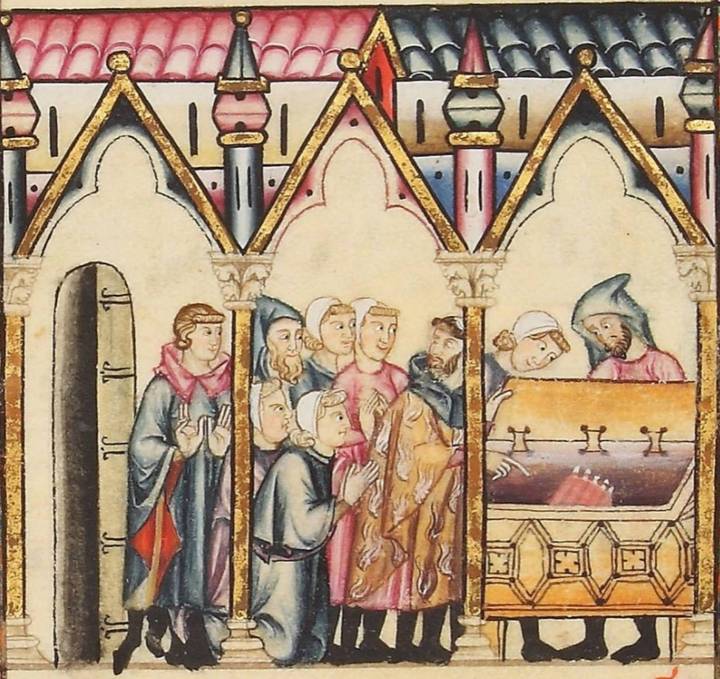

Illustrations for CSM 159.

Above: The pilgrims discovered they were one chop short.

Below: After hearing banging noises from inside a chest, the pilgrims

opened it “and they saw their chop jumping from side to side.”

In CSM 73, a monk was wearing a fine white chasuble, the ornate sleeveless outer vestment worn by Catholic priests. He tripped on a stone, spilling red communion wine all over the garment, “and it looked as though fresh blood had been poured on it.” When the monk found the stain to be indelible, he prayed to Mary to save him from disgrace: “I shall never dare to show my face in the abbot’s presence nor associate with the other monks.” Mary made the chasuble “whiter than it had been before”, “such a miracle that many pilgrims came from far away to worship the white chasuble.” Again, the story ends with the display of the miraculous item: “many pilgrims came from far away to worship the chasuble.” The song does not explain any holy efficacy it may have, but in both songs the clear impression is given that a new relic has been created, to encourage believers and to stand as a signifier of Mary’s holy power.

The housing of relics: the reliquary

In CSM 362, unspecified “relics of this lady of great worth” were carried in “a very rich chest of gold to carry the relics in every procession.” Being fragmentary and therefore small, relics are both portable and in need of protection. For this, there was the reliquary. Typically the saint’s bone, chip of stone from a holy site, dust from physical remains and so on, was wrapped in linen or silk and stitched into a small pouch to keep the matter together which could otherwise potentially disperse or disintegrate. From the 7th century on there are surviving scraps of papyrus (in the earliest period) or parchment (later and more common), written on as labels to identify the contents. The relic and the label were then placed inside a reliquary, often lavish and ornate to reflect in material terms the spiritual value of the contents. One exceptional example is the Holy Thorn reliquary, dated 1390-97, now in the British Museum.

The front and two details of the late 14th century Holy Thorn Reliquary, originally in Paris, now

in the British Museum. It is made of gold, richly enamelled and set with rubies, pearls and sapphires;

30.5cm high, 13cm wide at the base, 15cm at its widest point.

(As with all pictures, click to see larger in new window.)

The power of relics: a part has the power of the whole

It follows from the partial nature of relics – there is no whole True Cross or complete volume of holy blood – that any part stands for the presence of the whole, and has the full power of the whole. The woman who “had been bleeding for twelve years” in Mark’s Gospel 5: 25-34 did not touch Jesus’ body, but his clothes, and that small contact was enough to cause the healing miracle. There is, then, no minimum requirement of holy presence: any amount of holiness is sufficient for a miracle. In the same way, the clerics at Thomas Becket’s shrine offered limitless ampullae of Thomas’ much-diluted blood, and the dilution did nothing to weaken its supposed efficacy.

We see this in the power of the relics described in the Cantigas. In CSM 35, a fire destroyed everything else in the church at Lyon du Rhône except relics of the Virgin’s milk and hair, which stood for the presence of her whole person. Similarly, in CSM 257, King Alfonso had numerous unspecified relics in Seville “of Holy Mary and male and female saints, through which God worked miracles”. He left them unattended while he lived in Castile for 10 years. On his return, he “found all the other relics badly damaged and the chests in which they lay all broken. However, those of Holy Mary were well preserved, for she prevents harm to her things.”

(In both of these stories, Mary’s miracles were for the benefit of herself, and clearly she thought only her relics were worth saving, the church of her worshippers and the items of other saints being of no value. For more on the Virgin’s narcissism, see The Virgin’s vengeance and Regina’s rewards: the surprising character of Mary in the Cantigas de Santa Maria by clicking here.)

In CSM 257, Alfonso returns to Seville to find all his relics damaged

except those of Holy Mary, which she has prevented from harm.

The business of relics: the pilgrimage franchise, stolen bones and foreskins

Despite the smallness and portability of relics, they nearly always remained in one place: churches would associate and identify themselves with their particular location and the relics therein. We see this constantly in the Cantigas, where Mary not only has universal titles, “Holy Mary”, “the Mother of God”, “Lady of Great Worth” and so on, but multiple local identities, each tied to a particular shrine, “Holy Mary of Montserrat”, “Holy Mary of Salas”, “Holy Mary of Rocamadour”, “Holy Mary of Terena”, “Holy Mary of Villa-Sirga”, “Holy Mary of Albesa”, “Holy Mary of Castrogeriz”, and so on.

The reason for this localism stems from the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 787, which declared that every consecrated altar should contain sacred relics. Thus the numbers of relics proliferated and the holding of holy artefacts became a commercial industry. It would not be stretching the point to see the business of pilgrimage as a money-making franchise, acting in a similar way to McDonald’s or Subway today. The franchiser, the Catholic Church, provides the brand (forgiveness of sins; eternal heaven), the sales pitch (you’re all going to hell without our solution; we have the only truth; only our truth will wash your sins clean; shorten your waiting time in purgatory; get healed), and the monopoly on the sales product (the sole authorisation of saints and therefore their shrines), expanding the brand through other people’s money while retaining the ultimate position of power. The franchisees, the local pilgrimage sites with their local relics, have the advantage of the umbrella organisation’s familiar international profile while promoting their local brands of holy artefacts and efficacious healing. The franchisee’s income from shrine souvenirs, donations and indulgences is divided between the clergy, church building programmes, and the poor – or, put commercially, the franchisee’s profits are divided between local franchisee partners (clergy), business expansion (church building programmes), and charitable donations (the poor).

The business of pilgrimage in modern-day Bethlehem.

The proliferation of relics meant that any church was potentially a place of pilgrimage but, with so many sites for the pilgrim to choose from, a church had to prove its relics were extra-special and/or greater in number to be ahead of market competition. In all such contexts, there is the potential for commercial sabotage, and CSM 316 gives just such an example. Martim Alvítez, a “troubadour priest” in Alenquer, Portugal, saw that “across the river from the city miraculous powers were discovered … They built an altar there in honour of the glorious lady, the virgin mother of God, so that pilgrims came there from far and wide, for she performed many of her miracles in that place, healing the lame and crippled and blind.” As a result, Martim Alvítez’s “heart grew heavy, because he lost the offerings of his church on account of the other one”. He “set fire to [the other church] and thus burned it down”. The Virgin was distressed, and Jesus took revenge by blinding Alvítez in front of a crowd. He immediately confessed, said he deserved it, and rebuilt the church with lime and stone. At the first mass in the rebuilt church, his sight was restored and he wept. His sabotage revealed and the penalty enacted, his crime hadn’t paid because The Ultimate Franchiser had invested in the local competition. Good earthly business and heavenly holy favour went hand in hand.

Above, left to right: Relics of the True Cross in the Schatzkammer, Vienna;

Santo Toribio de Liébana, Spain; and the Serbian Monastery of Visoki Dečani.

Below, left to right: Relics of the True Cross in Notre Dame de Paris;

another in Notre Dame de Paris; and in the treasury of the former

Premonstratensian Abbey in Rüti, Switzerland.

The Holy Prepuce or Holy Foreskin of the infant Jesus – or one of them, he had several – held at the Basilica of the Holy Blood, Bruges, Belgium.

Others in the relic business did get away with it. In 1087, a church in Bari, Italy, paid thieves to steal the remains of Saint Nicolas from a church in Myra, Turkey. They succeeded, and Bari was proud to be the town that stole and owned Nicolas’ bones. Other churches, rather than steal, faked. There are hundreds of European churches which all claim to have pieces of the True Cross, some of which are pictured above. The Holy Foreskin, removed from Jesus at his brit milah, his circumcision on the eighth day of his earthly life, was claimed by Charlemagne to have been given to him by an angel, and he gave it as a gift to Pope Leo III in c. 800. In 1149, Thierry d’Alsace, Count of Flanders, brought a vial of gold and glass to Bruges, Belgium, with a blood-like substance inside, saying it was the Holy Foreskin. He had received it from the Patriarch of Jerusalem as a reward for his contribution to the First Crusade in the Holy Land. It is now held at the Basilica of the Holy Blood, Bruges. However, the monks of Charroux, France, claimed in the 16th century that their Holy Foreskin was the real one, and Pope Clement VII agreed. Whether or not we believe angels give foreskins to kings as presents, there are now 21 churches across Europe which claim to have it, with powers which include the protection of women in childbirth. In 1166, a 33 year old woman named Rosalia – later Saint Rosalia – died in a cave on Mount Pelligrino, Palermo, Sicily. In 1624 a plague swept through Palermo, and one woman claimed to have seen a vision of Rosalia, instructing that her bones should be found. Duly, they were found by a hunter looking in a cave. While on honeymoon in Palermo in 1825, British geologist William Buckland examined them, and found them to be the bones of a goat.

Questioning the authenticity of holy relics brings a dreadful penalty, as CSM 61 shows. This is “a miracle which happened in Soissons. There is a book there all filled with miracles of that place and no other which the Mother of God performed by night and day.” The book cited is very likely to be the Miracles de la Sainte Vierge or Les Miracles de Nostre-Dame (Miracles of the Blessed Virgin or The Miracles of Notre Dame), a collection of poems to the Virgin in vernacular Middle French, set to the popular troubadour and trouvère melodies of the day by Benedictine monk, Gautier de Coincy, who was prior of Soissons from 1233. It is very likely that King Alfonso’s songwriting was based on that of Gautier de Coincy: certainly, it is in the same mould. CSM 61 tells the tale of “a churlish fellow” – a “foolhardy cowherd” in other versions of the story – who said “It is senseless to believe in [the shoe of the Virgin at Soissons convent], for the shoe could not have been so well preserved and not have rotted away after such a long time has passed.” As a result, when he was travelling with four companions, “his mouth became twisted in such a way as to frighten anyone who saw it”, as shown in the manuscript illustration below left. “He felt such pain that he thought his eyes would pop out of his head. In this distress, he returned on a pilgrimage to where the shoe was”, as shown below right.

As with all pictures, click to see larger in new window.

Returning as a pilgrim to the convent, he prostrated himself in front of the altar, exclaiming his foolishness in doubting. “Then, for his atonement, the abbess of the convent rubbed the shoe across his face and made it whole and sound again as it was before”, as shown below left. “When the peasant realised that he was completely cured, he was released from the master to whom he belonged and came to the convent where he is a servant to this day”, as shown below right.

This warning against doubting relics was a popular story, included internationally in five other surviving medieval collections in addition to Gautier’s and Alfonso’s. The clear intention of the story is to scare anyone with an enquiring mind into silence: the church and its collection of relics is not to be questioned. The same motivation is behind a story set in 12th century France. In 1176, 6 years after the murder of Thomas Becket, 3 years after his canonisation, John of Salisbury became Bishop at Chartres Cathedral, bringing with him an ampulla of Saint Thomas’ water. A stonecutter named Pierre was struck down by God after publicly voicing his doubt that Saint Thomas could perform miracles. In an attempt to cure him, John of Salisbury laid Pierre on the tomb of Leobinus (Lubin in French), a 6th century saint and bishop. When this failed, he tried the power of the sainte chemise, a silk shift or chemise which belonged to the Virgin, held by the cathedral since the 9th century (as described above). This also had no effect. Only when Pierre kissed the ampulla of Saint Thomas’ water, then drank the water in which the ampulla had been washed, was he granted divine forgiveness and release from his affliction. In penance for his sin and in thanks for his cure, Pierre vowed to visit Canterbury, home of Saint Thomas. The message: don’t doubt, don’t question, or God will punish you until you recant.

The local and the universal

The _New Testament_’s history of the early church, Acts of the Apostles, has the apostle Paul say, “The God who made the world and everything in it is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands. And he is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything. Rather, he himself gives everyone life and breath and everything else.” Even so, medieval Christianity relied upon the temporal, the temple, the relic, as a conduit for the holy, and relied upon the constant praising of and obeisance to the divine.

There is an implicit tension in relicry between the local, temporal nature of pilgrimage and the universal, eternal, holy presence. While “God … is the Lord of heaven and earth and does not live in temples built by human hands”, divine presence is fractured into competing locales, competing pilgrimages, competing relics of competing efficacy, even competing Virgin Marys “of Montserrat”, “of Salas”, “of Rocamadour”, and so on. In this way, the medieval practice of pilgrimage was reminiscent of George Orwell’s “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” (Animal Farm, 1945): ‘Omnipresent God is everywhere, but he is more everywhere in some places than others’.

At the other extreme of meaning, while universal holy presence is localised and splintered across myriad competing pilgrimage destinations and relics, the relic also unites all time in a single eternity: the whole of Christian cosmology is encapsulated in each fragment of saint’s hair, cloth or wood. The relic looks backwards to commemorate God’s plan of salvation, holy events in Christ’s life, or Mary’s life, or the death of martyrs; it also represents the pilgrim’s present need for health and forgiveness; and it looks forward to God’s judgement, resulting in redemptive heaven or punishing hell. This idea of the local in contact with the universal, the temporal in contact with the eternal, is expressed in every song of the Cantigas. In the pilgrimage story of CSM 173, for example, doctors have failed and Mary is the only possible hope of healing: “He had gone to many doctors, but they did him no good. Therefore, he had placed all his trust in Holy Mary. He went at once to Salas to pray to her who holds the world in her command”.

Rocamadour, the site of the miracle of the stolen chop and other stories in the Cantigas, as it is today.

This is the key to understanding the medieval idea of pilgrimage, the Marian miracle stories circulating in 13th century Europe and the Cantigas which put them into verse. Today an animated chop of meat, a man who wouldn’t hang, a talking sheep, a flying chair, a life-saving chemise, and a shoe that heals by being rubbed on the face seem fanciful at best, dangerously illogical at worst. But such events were completely in keeping with a worldview in which the supernatural rules the natural, the eternal rules the temporal, heaven rules Earth, and God and Mary rule their people through divinely-appointed kings, such as Alfonso, and aid their people through their miracle-working shrines. Thus the unpredictability of life-threatening illness, life-threatening weather and life-threatening enemies is conceptually tamed by the hope of supernatural help, healing and redemption. One only has to believe the truth, which is a property of power and authority, and be subservient and sinless.

~ ~ ~ 0 ~ ~ ~

In modern literature, Alfonso X is usually presented as a wise, tolerant king who took steps to create a multicultural court and a liberal kingdom of learning. The next article examines the evidence for these claims in relation to Moors and Jews, as represented in the Cantigas and in the king’s law codes.

Translation credit

The translations of the Cantigas de Santa Maria are by Kathleen Kulp-Hill – see bibliography. Since the syntax of different languages makes it impossible to create a meaningful line by line literal translation that rhymes in all the same places, Kathleen Kulp-Hill’s translation is presented in her book in verses without retaining individual lines. This is replicated in the above article.

My role in creating English verses in the videos that accompany these articles was to recreate, as far as possible, the original syllable count and rhyme scheme. The versification in English of CSM 159 and the musical arrangement are © Ian Pittaway.

Bibliography

Arnold, John H. (2014) The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barber, Richard (1992), Bestiary, MS Bodley 764. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press.

Bell, Adrian R., & Dale, Richard S. (2011) The medieval pilgrimage business. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Boehm, Barbara Drake (2011) Relics and Reliquaries in Medieval Christianity. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Bowers, Barbara S., & Keyser, Linda Migl (eds.) (2016) The Sacred and the Secular in Medieval Healing: Sites, Objects, and Texts. Abingdon: Routledge.

Brittain, C. Dale (2016) Relics and reliquaries. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Centre for the Study of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (2005) Oxford Cantigas de Santa Maria Database. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Dickson, Gary (2007) The Children’s Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dyas, Dee; Gill, Miriam; Webb, Diana; Riches, Sam; Phillips, Helen; & Weiss, Judith (2012) Pilgrims and Pilgrimage: Patterns of Pilgrimage in England c.1100-c.1500. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Fremantle, W. H. et al (transl.) (1893) Jerome, Letters 108-10, translated by Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, second series, volume 6. Buffalo, N.Y.: Christian Literature Publishing Co.

Geary, Patrick J. (1978) Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goldberg, Eddy (2018) The Benefits of the Franchise Model. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Klein, Holger A. (1999) Relics & Reliquaries: Portable Altar of Countess Gertrude. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Kulp-Hill, Kathleen (2000) Songs of Holy Mary of Alfonso X, The Wise. A translation of the Cantigas de Santa Maria. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies.

Saul, Nigel (1997) The Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simkin, John (2014) Pilgrimage. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Smith, Julia M. H. (2010) Portable Christianity: Relics in the Medieval West (c. 700–1200). [It was online here – but gone when I last checked.]

Sorabella, Jean (2011) Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe. [Online – click here to go to website.]

Switek, Brian (2009) The Father, the Son, and the Holy Goat. [Online – click here to go to website.]

© Ian Pittaway. Not to be reproduced in any form without permission. All rights reserved.