The Mount Everest Economics That Take Us to the Margin (original) (raw)

In the past, writing about Mount Everest, I’ve said that the summit is at 29,028 feet.

I was wrong.

Agreeing for the first time, China and Nepal said the right number is 29,031.69 feet.

It’s tough to measure a mountain. Figuring out where sea level starts is not quite clearcut. In the past, Nepal used the Bay of Bengal and wound up with the summit at 29,028 feet while China started with the Yellow Sea and got 29,017. Then, for the position of the peak you have to decide whether to include the snow cover. And, it gets even more complicated because shifting tectonic plates can lift the mountain and earthquakes make it sink.

Mount Everest Economics

More and more people want to scale those 29,000 feet.

From a trickle to an avalanche, the traffic on Everest has multiplied. One reason was the onset of expedition companies that facilitated and marketed the adventure. In addition, the equipment and weather forecasting got better. Changing the size of the groups also made a difference. At first more climbers supported the attempts of a few to make it to the summit. More recently, small groups, with all hoping to reach the top, ascend together.

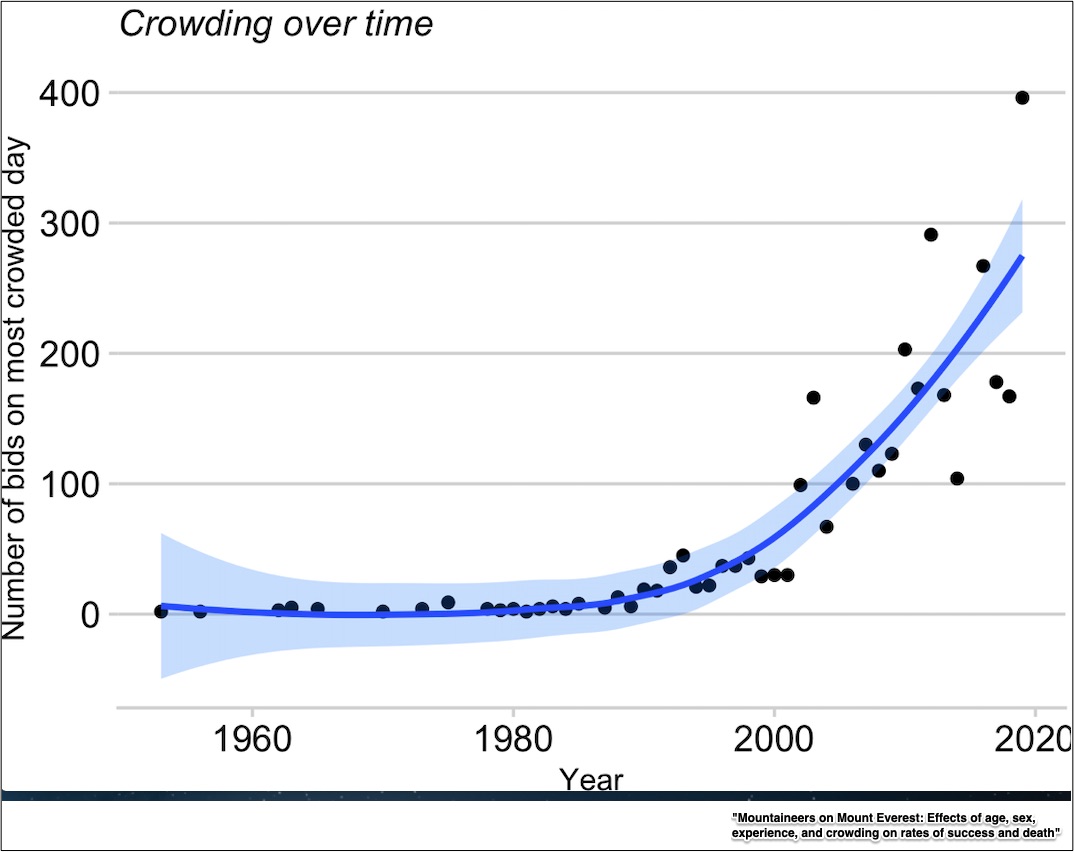

You can see the numbers rising:

One result has been traffic jams at the summit:

These are the crowding numbers:

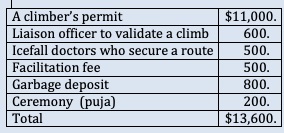

Still, Nepal refuses to cap permits because Mount Everest tourism boosts its 24billionGDPbyapproximately10percent.Itsfeesandlicensesgenerateapproximately24 billion GDP by approximately 10 percent. Its fees and licenses generate approximately 24billionGDPbyapproximately10percent.Itsfeesandlicensesgenerateapproximately13,600 a person:

Other climbing expenses include equipment, guides, Sherpas, travel, food, meds. Together, the whole Everest package averages 66,000but(reputedly)canclimbto66,000 but (reputedly) can climb to 66,000but(reputedly)canclimbto160,000.

Our Bottom Line: Thinking At The Margin

Economists like to say that we think at the margin. The margin is that imaginary line where we can add some sleep or drive faster or study longer or eat more. Choosing a budget, Congress is always at the margin when it allocates extra dollars to different agencies.

Similarly, the tale of Mount Everest is a story about climbing margins. It involves additional permits, more revenue, sherpas, and expeditions. Perhaps most crucially, climbers make decisions at the margin. They think about margins of safety when debating whether to scale the summit or not.

We would be remiss though if we did not add that all of these margins relate to the fixed quantity of the mountain that is supplied and the increasing goods and services that we demand. The result is too much traffic.

Let’s end though with where we began. A few feet at the margin might not make a difference for a 29,000 foot mountain. But it does.

My sources and more: For Mount Everest, the BBC, and the Hustle were ideal complements. Then, for a slightly different perspective, this blog focuses on supply and demand. However, for the most accurate information, I recommend this paper from the University of Washington.

Our featured image, Mount Everest, is from the BBC.