How the Port Strike Reflects Continuing Automation (original) (raw)

The International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA) is threatening to strike over wages and automation.

The automation issue began with a box.

The Box

Long before today, our story begins In 1956 when Malcom McLean rigged an oil tanker with 58 of his trailer trucks. Then, just the cargo containers were placed in slots on the vessel in Newark N.J. When they arrived in Houston, again, only the containers were unloaded, and shipped to stores and warehouses by rail or truck.

The container was revolutionary.

Before the container, t-shirts, flour, and bananas were packed in barrels or bags or crates. Transported by truckers to waterfront docks, it could have taken weeks and gargantuan worker hours to load them onto ships.

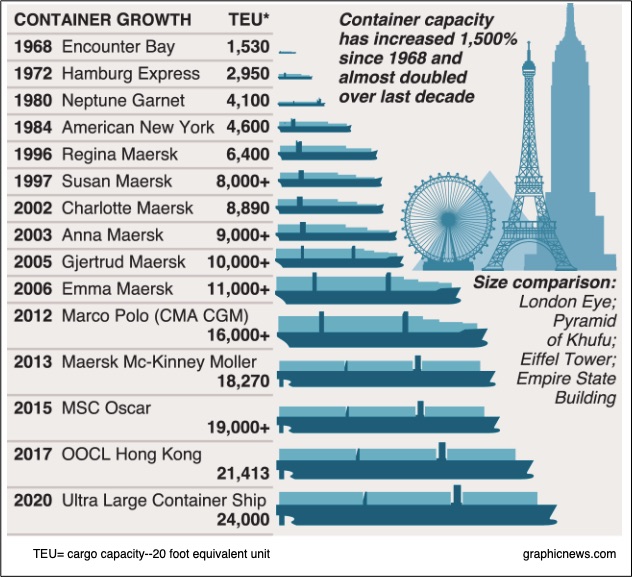

Leaping to 2015, we have just one container ship carrying 39,000 cars, 117 million pairs of sneakers, or a whopping 900 million cans of dog food. The container in our featured image can carry 82,880 t-shirts. Whereas moving your cargo 1,000 feet from the street to a ship could have taken as long as an entire ocean trip, instead plummeting time and cost have remade contemporary shipping:

The Port Strike

The box was only the beginning.

The ILA contract with the United States Maritime Alliance (USMX) expires on September 30. With the impact of a strike rippling far beyond the East and Gulf Coast ports where the strike would take place, it would most hit time sensitive industries like chemicals, agriculture, automobile parts. Also, the upcoming holiday season looms large.

Objecting to automation and robotics, the union opposes a system that autonomously processes trucks without ILU labor. They also expect a job audit that indicates the technology personnel that would be hired. As for wages, they are reputedly negotiating for a 77% wage increase over the 6-year spread of a new contract.

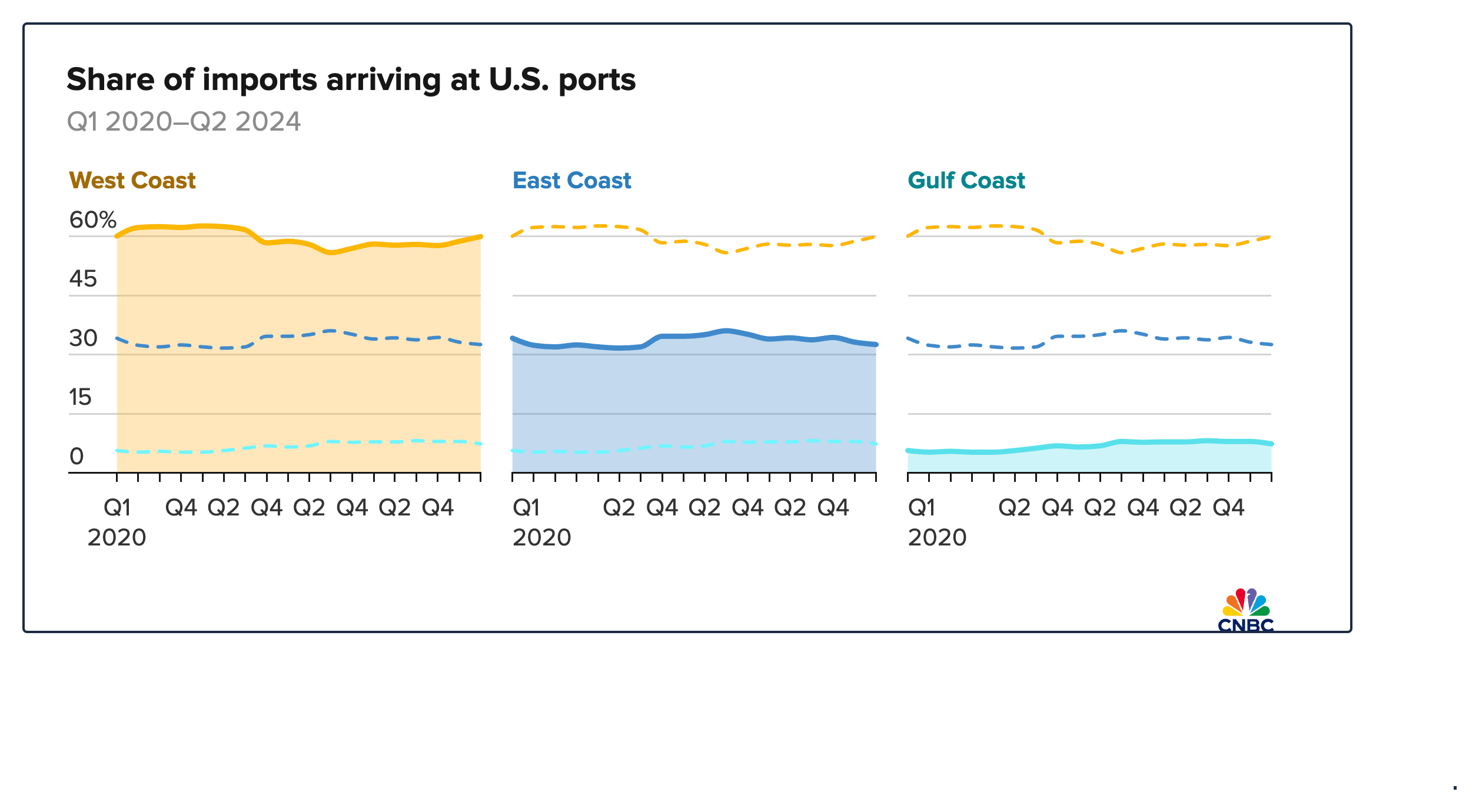

Imagined as cargo, the East Coast graph reflects the 74,000 shipping containers a day that would not arrive during a strike:

Our Bottom Line: Structural Change

Characterized by new land, labor, and capital, port automation represents a structural transition in the economy. Like the bowling alleys that used to need pinsetters and the typewriters we wrote with, the factors of production continue to change at our ports.

Described by Joseph Schumpeter as creative destruction, the change is painful. From dockworkers’ perspective, livelihoods will evaporate. At the same time, port managers and shippers and terminal owners have to plan for a slew of new jobs that we call structural change. Referring to new factors of production, structural change transforms our labor and our capital. It requires new skills and new technology.

In 1956, it was a box. Now there is so much more.

My sources and more: For the facts, these CNBC articles, here and here, are a good place to start. From there, these supply chain websites, here, here, and here were handy for their lens. Then, I found out more about the union’s position at News 12 and the book that tells the whole box story. But finally, do compare the ILA’s concerns to the UAW.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a previous econlife post.