Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Background, Indications, Contraindications (original) (raw)

Overview

Background

Whereas it is true that no operation has been more profoundly affected by the advent of laparoscopy than cholecystectomy has, it is equally true that no procedure has been more instrumental in ushering in the laparoscopic age than laparoscopic cholecystectomy has. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has rapidly become the procedure of choice for routine gallbladder removal and is currently the most commonly performed major abdominal procedure in Western countries. [1]

A National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus statement in 1992 stated that laparoscopic cholecystectomy provides a safe and effective treatment for most patients with symptomatic gallstones and has become the treatment of choice for many patients. [2] This procedure has more or less ended attempts at noninvasive management of gallstones.

The initial driving force behind the rapid development of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was patient demand. Prospective randomized trials were late and largely irrelevant because advantages were clear. Hence, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was introduced and gained acceptance not through organized and carefully conceived clinical trials but through acclamation.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy decreases postoperative pain, decreases the need for postoperative analgesia, shortens the hospital stay from 1 week to less than 24 hours, and returns the patient to full activity within 1 week (compared with 1 month after open cholecystectomy). [3, 4] Laparoscopic cholecystectomy also provides improved cosmesis and improved patient satisfaction as compared with open cholecystectomy.

Although direct operating room and recovery room costs are higher for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the shortened length of the hospital stay leads to a net savings. More rapid return to normal activity may lead to indirect cost savings. [5] Not all such studies have demonstrated a cost savings, however. In fact, with the higher rate of cholecystectomy in the laparoscopic era, the costs in the United States of treating gallstone disease may actually have increased. To this must be added the costs associated with treating bile duct injuries (BDIs) sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. [6]

Trials have shown that laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients in outpatient settings and those in inpatient settings recover equally well, indicating that a greater proportion of patients should be offered the outpatient modality. [7]

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has received nearly universal acceptance and is currently considered the criterion standard for the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis. Many centers have special “short-stay” units or “23-hour admissions” for postoperative observation following this procedure. [7]

Data from all over the world have, however, shown that the risk of a BDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is about 0.5%—that is, about two to three times the risk previously reported for open cholecystectomy. [8]

Indications

The general indications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy are the same as those for the corresponding open procedure. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy was originally reserved for young and thin patients, it is now offered to elderly and obese patients as well; in fact, these latter patients may benefit even more from surgery through small incisions.

Asymptomatic (silent) gallstones

The widespread use of diagnostic abdominal ultrasonography (US) has led to increasing detection of clinically unsuspected asymptomatic gallstones. This development, in turn, has given rise to a great deal of controversy regarding the optimal management of asymptomatic gallstones. [9]

Cholecystectomy is not indicated in most patients with asymptomatic (silent) gallstones, because only 2-3% of these patients go on to become symptomatic each year. For an accurate determination of the indications for elective cholecystectomy, the risk posed by the operation (with individual patient age and comorbid factors taken into account) must be weighed against the risk of complications and death if the operation is not done. [10]

Patients who are immunocompromised, are awaiting organ allotransplantation, or have sickle cell disease are at higher risk for the development of complications and should be treated irrespective of the presence or absence of symptoms.

Additional reasons to consider prophylactic laparoscopic cholecystectomy include the following:

- Calculi greater than 3 cm in diameter, particularly in individuals in geographic regions with a high prevalence of gallbladder cancer

- Chronically obliterated cystic duct

- Nonfunctioning gallbladder

- Calcified (porcelain) gallbladder [9]

- Gallbladder polyp larger than 10 mm or showing a rapid increase in size [11]

- Gallbladder trauma [10]

- Anomalous junction of the pancreatic and biliary ducts without cystic dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD), because of a very high risk of gallbladder cancer

Morbid obesity is associated with a high prevalence of cholecystopathy, and the risk of developing cholelithiasis is increased during rapid weight loss. Routine prophylactic laparoscopic cholecystectomy before Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is controversial, but laparoscopic cholecystectomy should clearly precede or be performed concurrently with RYGB in patients with a history of gallbladder pathology. [12]

A normal gallbladder is often removed as a part of another surgical procedure (eg, right-lobe donor hepatectomy, liver resection, excision of a choledochal cyst, or pancreatoduodenectomy).

Symptomatic gallstone disease

Biliary colic with sonographically identifiable stones in the gallbladder is the most common indication for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. [10, 13]

Biliary dyskinesia should be considered in patients who present with biliary colic in the absence of gallstones, and a cholecystokinin–diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid (CCK-DISIDA) isotope scan should be obtained. The finding of a gallbladder ejection fraction lower than 35% at 20 minutes is considered abnormal and constitutes another indication for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. [14]

Complex gallbladder disease

Acute cholecystitis, if diagnosed within 72 hours after symptom onset, can and usually should be treated laparoscopically. Beyond this 72-hour period, inflammatory changes in surrounding tissues are widely believed to render dissection more difficult as a consequence of increased vascularity and friability of the tissues. This may, in turn, increase the likelihood of conversion to an open procedure to 25%. Randomized control trials have not borne out this 72-hour cutoff and have shown no difference in morbidity (though only when the procedure is performed by expert and experienced surgeons).

Other options include conservative management followed by interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy after 4-6 weeks and percutaneous cholecystostomy. [15, 16, 17]

Gallstone pancreatitis

Once the clinical signs of mild-to-moderate biliary pancreatitis have resolved, laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be safely performed during the same hospitalization. Patients diagnosed with gallstone pancreatitis should first undergo imaging to rule out the presence of choledocholithiasis. This can be achieved by means of preoperative US, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic US (EUS), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or intraoperative cholangiography (IOC). [18] The chances of finding a stone in the CBD decrease with increasing time after the attack of acute pancreatitis.

In cases of acute moderate-to-severe biliary pancreatitis (according to the Ranson criteria), laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be delayed to a lter date when the inflammation of acute pancreatitis has settled. [19]

Choledocholithiasis

The following treatment options are available for patients found to have choledocholithiasis:

- Preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone extraction

- Laparoscopic CBD exploration with or without T-tube placement

- Open CBD exploration with or without T-tube placement

- Postoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy

In a patient with documented choledocholithiasis, a single laparoscopic procedure that treats both cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis in a single setting is preferable. This approach appears to be cost-effective and to be associated with a shorter hospital stay than a two-stage procedure (ie, preoperative endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy) would be. In experienced hands, laparoscopic CBD exploration appears to have high success rates (75-91%). The exact algorithm followed, however, depends on local expertise.

Mirizzi syndrome

In 1948, Mirizzi described an unusual presentation of gallstones that, when lodged in either the cystic duct or the Hartmann pouch of the gallbladder, externally compressed the common hepatic duct (CHD), causing symptoms of obstructive jaundice.

Although an initial trial of dissection may be performed by an experienced laparoscopic biliary surgeon, one must be prepared for subtotal (partial) cholecystectomy or for conversion to open operation and for biliary reconstruction. Endoscopic stone fragmentation at ERCP, with papillotomy and stenting, is a viable alternative to operative surgery for treatment of Mirizzi syndrome presenting with acute cholnagitis in the acute setting. [20] Subsequent cholecystectomy may be performed later. [21]

Cholecystoduodenal fistula

Cholecystoduodenal fistula does not represent an absolute contraindication for laparoscopic surgery, though it does necessitate careful visualization of the anatomy and good laparoscopic suturing and stapling skills.

Gallstone ileus

Patients with cholecystoduodenal fistula leading to gallstone ileus should undergo exploratory laparotomy and removal of the stone, followed by exploration of the remainder of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract for additional stones. The fistula may be addressed at the time of the initial procedure but is probably better addressed at a second operation 3-4 weeks later, after inflammation has subsided. [21]

Acalculous cholecystitis

A substantial proportion of patients with acalculous cholecystitis are too ill to undergo surgery. In these situations, percutaneous cholecystostomy guided by US or computed tomography (CT) is advised. As many as 90% of these patients demonstrate clinical improvement. Once the patient has recovered, the cholecystostomy tube can be removed without sequelae; this usually takes place at about 6 weeks. Interval cholecystectomy is not necessary. [22]

Incidental gallbladder cancer

Gallbladder cancer may be an incidental finding on histopathology after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with an incidence ranging from 0.3% to 5.0%. [23, 24, 25] Uncertainty about the diagnosis, lack of clarity regarding the degree of tumor spread, or postoperative identification of cancer on pathologic examination of a routine cholecystectomy specimen should warrant early reoperation.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have advocated simple cholecystectomy (which has already been done) as definitive treatment for patients with mucosal (T1a) disease and a negative cystic duct margin; all other patients (ie, those with involvement of muscle or beyond, a positive cystic duct margin, or a positive cystic lymph node) should undergo repeat operation for completion extended (radical) cholecystectomy (which includes hepatic resection, lymphadenectomy and, sometimes, bile duct excision). (See Gallbladder Cancer.)

Before reoperation, distant metastases should be excluded by means of a detailed clinical examination that includes examination both per rectum and per vaginam, examination for supraclavicular lymph nodes, and CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest and abdomen (and, possibly, positron emission tomography [PET]).

Intraoperative identification of cancer during laparoscopic cholecystectomy used to be an indication for conversion to an open procedure. A malignant gallbladder can, however, be removed laparoscopically. Gallbladder perforation and bile spill should be avoided, and the gallbladder should be extracted in a bag to reduce the risk of port-site recurrence. Excision of all ports or the port of extraction is not mandatory and is not generally preferred, in that it has not been shown to improve survival. [26]

Special populations

Children

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe and effective treatment for most children diagnosed with biliary disease. Although it takes longer to perform than open cholecystectomy does, it results in less postoperative narcotic use and a shorter hospital stay, as has been the case in the adult literature. [27]

Patients with cirrhosis

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is safe in many patients with cirrhosis. The laparoscopic approach should be considered the procedure of choice in the patients with Child class A and B cirrhosis and symptomatic gallstone disease. Patients with Child class C cirrhosis who present with symptomatic cholelithiasis or cholecystitis should be considered for medical management if they are transplant candidates. Some consider repeated episodes of cholecystitis in a patient with Child class C cirrhosis an indication for transplant. [28, 29]

Diabetics

The presence of diabetes mellitus, in and of itself, does not confer sufficient risk to warrant prophylactic cholecystectomy in asymptomatic individuals with gallstones. It should be kept in mind, however, that acute cholecystitis in a patient with diabetes is associated with a significantly higher frequency of complications such as gangrenous cholecystitis and infectious complications, such as sepsis.

Pregnant women

Biliary colic or uncomplicated cholecystitis in a pregnant patient is treated with conservative management followed by elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The use of antibiotics, analgesics, and antiemetics helps most pregnant women avoid surgical intervention. Surgery is generally indicated for patients with recurrent acute cholecystitis that does not respond to maximal medical therapy.

Classically, the second trimester is considered the safest time for surgical treatment. This is because of the increased risk of spontaneous abortion and teratogenesis during the first trimester and the increased risk of premature labor and difficulties with visualization of the gallbladder in the third trimester.

At one time, pregnancy was considered to be an absolute contraindication for the laparoscopic approach, out of concern for the potential trocar injury to the uterus and the unknown effects of pneumoperitoneum on the fetal circulation. However, this concern has not been borne out in the literature, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy is now considered safe in pregnant patients.

Reported predictors of fetal complications are laparoscopy, diagnosis, admission urgency, year, hospital size, location, teaching status, and high-risk obstetric cases; predictors of maternal complications are an open procedure and greater patient comorbidity. [30]

Recommendations for pregnant patients who must undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy include the following:

- Placement in the left lateral recumbent position to shift the weight of the gravid uterus off the vena cava

- Maintenance of insufflation pressures between 10 and 12 mm Hg

- Monitoring of maternal arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2) - This may be done by measuring either arterial blood gases or end-tidal CO2; the former may be more accurate

Other recommendations are as follows [31] :

- Avoidance of rapid changes in patient position

- Avoidance of rapid changes in intraperitoneal pressures

- Supraumbilical placement of the first port

- Use of open technique for the first (umbilical) port placement

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy include an inability to tolerate general anesthesia and uncontrolled coagulopathy. Patients with severe obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure (eg, cardiac ejection fraction < 20%) may not tolerate carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum and may be better served with open cholecystectomy if cholecystectomy is absolutely necessary.

At one time, gallbladder cancer was considered a contraindication for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but laparoscopic extended (radical) cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer has since been reported to have oncologic results equivalent to those of the open operation. [32] If there is any suspicion of gallbladder cancer, laparoscopic simple cholecystectomy should not be performed. If gallbladder cancer is diagnosed intraoperatively, the operation must be converted to an open procedure. Theoretically, an open procedure allows a more controlled performance, with less chance of spillage; in addition, lymph nodes can be sampled intraoperatively to facilitate staging. [33]

Many conditions once felt to be contraindications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy (eg, gangrenous gallbladder, empyema of the gallbladder, cholecystoenteric fistulae, obesity, pregnancy, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, previous upper abdominal procedures, cirrhosis, and coagulopathy) are no longer considered contraindications but are acknowledged to require special care and preparation of the patient by the surgeon and careful weighing of risk against benefit.

As surgeons have accumulated extensive experience with the laparoscopic technique, these contraindications have been discounted, and reports of successfully performed cases have become abundant. [34, 35]

Technical Considerations

Anatomy

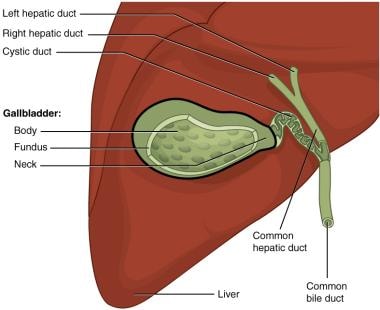

The extrahepatic biliary tree consists of the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts, the CHD, the CBD, the cystic duct, and the gallbladder (see the image below).

Gallbladder anatomy. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons | OpenStax College, Anatomy & Physiology (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2425\_Gallbladder.jpg). Creative Commons BY 3.0 Deed (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped reservoir of bile, 7-10 cm in length and 2.5-5 cm in diameter, that is situated on the inferior surface of the liver, partially covered by peritoneum. It lies at the junction of the right and left hemilivers, between segments 4 and 5. The gallbladder is divided into four parts: fundus, body, infundibulum, and neck. Normally, it contains up to 60 mL of fluid, but it may be distended to a capacity as high as 300 mL in certain pathologic conditions. [36]

As the neck of the gallbladder joins the cystic duct, it makes an S-shaped bend. The Hartmann pouch is an outpouching of the wall in the region of the neck. This pouch varies in size, largely as a result of dilatation or the presence of stones. [14] A large Hartman pouch may easily obscure the cystic duct within the triangle of Calot.

The gallbladder is supplied by a single cystic artery, which is most commonly a branch of the right hepatic artery but may also originate from the left hepatic, proper hepatic, gastroduodenal, or superior mesenteric artery. The cystic artery typically courses superior to the cystic duct. Its length varies, depending on which artery it originates from and whether it enters into the neck or the body of the gallbladder. A double cystic artery may exist in 15% of the population. [37]

The cystic duct connects the gallbladder to the CHD to form the CBD. It is arguably the most important structure to be identified in a cholecystectomy. The cystic duct ranges from 1 to 5 cm in length and from 3 to 7 mm in width; an extremely short (< 1 cm) cystic duct may pose a substantial challenge in the dissection and placement of clips during cholecystectomy.

The CBD is 5-9 cm long and is divided into three segments: supraduodenal, retroduodenal, and intrapancreatic. It lies anterior to the portal vein and to the right of the proper hepatic artery, at the free border of the lesser omentum. The CBD runs behind the first part of the duodenum on top of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and lies in a groove on the posterior surface of the pancreatic head. It continues down the left side of the second part of the duodenum, joining the pancreatic duct to form the ampulla of Vater, which opens into the second part of the duodenum at the papilla. [38]

The triangle of Calot is an important landmark whose boundaries include the CHD medially, the cystic duct laterally, and the inferior edge of the liver superiorly. It contains the cystic lymph node of Lund (also known as the Calot node); it is also where the cystic artery branches off the right hepatic artery. This triangular space is dissected to allow the surgeon to identify, clip and divide the cystic duct and the cystic artery. The Calot node is the main route of lymphatic drainage of the gallbladder.

Accessory hepatic ducts, also known as the ducts of Luschka, connect directly from the hepatic bed to the gallbladder. The ducts drain a normal segment of the liver. When encountered during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, they should be clipped and divided to prevent a bile leak or a biliary fistula.

Best practices

The following measures may facilitate performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, reduce perioperative morbidity, or both:

- All ports should be inserted under direct vision

- Placing the patient in the reverse Trendelenburg position (head up) with the right side up permits gravity to assist in retraction and allows the structures to fall away from the operative field

- The use of a 30° laparoscope is optional but significantly improves visualization of the triangle of Calot from all sides

- The subxiphoid incision should be made in an oblique manner so it can be extended in case conversion to open cholecystectomy becomes necessary

- An additional 5-mm port placed in the left upper quadrant to retract a floppy liver or press down on a very fatty omentum or duodenum may be the key to success in a difficult case

- The liver bed should always be rechecked for bleeding before the gallbladder is completely removed

- A subtotal cholecystectomy may be an excellent option in cases of severe fibrosis or inflammation [39]

- Drains are not routinely placed but may be necessary in the event of (1) severe acute cholecystitis with significant inflammation, (2) suspicion of inadequate control of a duct of Luschka, or (3) subtotal cholecystectomy

- The drain may be placed laparoscopically and brought out through the most lateral of the 5-mm ports at the end of the procedure

Complication prevention

Major CBD injuries, though infrequent (0.2-0.3%%), can be devastating when they do occur (see Complications). Repairs for such injuries range from primary repair over a stent to hepaticojejunostomy. [3] Tricks that can help the surgeon avoiding this potentially serious complication include the following:

- Avoiding excessive cephalad traction on the gallbladder so as to prevent tenting and misidentification of the CBD as the cystic duct [40]

- Before clipping and transection, carefully identifying the cystic duct and artery in the critical view of safety (CVS) (see Conventional Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy) as the only two structures entering the gallbladder [41]

Litigation is much more common after laparoscopic cholecystectomy than after open cholecystectomy, for two apparent reasons. First, BDIs are more common with laparoscopic cholecystectomy; second, missed intraoperative injuries may be more common in laparoscopic cholecystectomy cases.

Recommendations for the prevention of BDIs include the use of the critical view of safety technique and bailout procedures (eg, subtotal cholcystectomy and early conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to open cholecystectomy) (see Conventional Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy). [42, 43, 44]

IOC has the potential to benefit the surgeon in the following two ways:

- Prevention of CBD injury - Although IOC may help prevent such injuries, [45, 46] the literature does not support using it on a routine basis; this modality is most likely to yield benefit if used selectively in cases of unclear anatomy [47]

- Identification of choledocholithiasis - Even if IOC is performed only selectively, many cholangiograms would have to be obtained to find a small number of stones; thus, IOC is not cost-effective for this purpose [48, 49]

In randomized trials, formal residency training, like routine use of IOC, has not been shown to reduce the number of BDIs.

Outcomes

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy remains an extremely safe procedure, with a mortality of 0.22-0.4%. [50, 51] Major morbidity occurs in approximately 5% of patients. [52] Complications include the following:

- Veress needle/trocar injury

- Hemorrhage

- CBD injury or stricture

- Gallstone spillage

- Litwin DE, Cahan MA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2008 Dec. 88 (6):1295-313, ix. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. NIH Consens Statement. 1992 Sep 14-16. 10 (3):1-28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Calland JF, Tanaka K, Foley E, Bovbjerg VE, Markey DW, Blome S, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy: patient outcomes after implementation of a clinical pathway. Ann Surg. 2001 May. 233 (5):704-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shea JA, Berlin JA, Bachwich DR, Staroscik RN, Malet PF, McGuckin M, et al. Indications for and outcomes of cholecystectomy: a comparison of the pre and postlaparoscopic eras. Ann Surg. 1998 Mar. 227 (3):343-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nealon WH, Bawduniak J, Walser EM. Appropriate timing of cholecystectomy in patients who present with moderate to severe gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis with peripancreatic fluid collections. Ann Surg. 2004 Jun. 239 (6):741-9; discussion 749-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kapoor VK, Pottakkat B, Jhawar S, Sharma S, Mishra K, Singh N, et al. Costs of management of bile duct injuries. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr-Jun. 32 (2):117-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lillemoe KD, Lin JW, Talamini MA, Yeo CJ, Snyder DS, Parker SD. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a "true" outpatient procedure: initial experience in 130 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999 Jan-Feb. 3 (1):44-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kapoor VK. Epidemiology of bile duct injury. Kapoor VK, ed. Post-cholecystectomy Bile Duct Injury. Singapore: Springer; 2020. 11-20.

- Gupta SK, Shukla VK. Silent gallstones: a therapeutic dilemma. Trop Gastroenterol. 2004 Apr-Jun. 25 (2):65-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Potts JR 3rd. What are the indications for cholecystectomy?. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990 Jan-Feb. 57 (1):40-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pejić MA, Milić DJ. [Surgical treatment of polypoid lesions of gallbladder]. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2003 Jul-Aug. 131 (7-8):319-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tucker ON, Fajnwaks P, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Is concomitant cholecystectomy necessary in obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery?. Surg Endosc. 2008 Nov. 22 (11):2450-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hunter JG. Acute cholecystitis revisited: get it while it's hot. Ann Surg. 1998 Apr. 227 (4):468-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Adams DB. The importance of extrahepatic biliary anatomy in preventing complications at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 1993 Aug. 73 (4):861-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, Lai EC, Wong J. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998 Apr. 227 (4):461-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Willsher PC, Sanabria JR, Gallinger S, Rossi L, Strasberg S, Litwin DE. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a safe procedure. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999 Jan-Feb. 3 (1):50-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pessaux P, Tuech JJ, Rouge C, Duplessis R, Cervi C, Arnaud JP. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. A prospective comparative study in patients with acute vs. chronic cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2000 Apr. 14 (4):358-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Uhl W, Müller CA, Krähenbühl L, Schmid SW, Schölzel S, Büchler MW. Acute gallstone pancreatitis: timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild and severe disease. Surg Endosc. 1999 Nov. 13 (11):1070-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mushinski M. Average charges for cholecystectomy open and laparoscopic procedures, 1994. Stat Bull Metrop Insur Co. 1995 Oct-Dec. 76 (4):21-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Roake JA. Mirizzi syndrome: Deja vu again. ANZ J Surg. 2007 Dec. 77 (12):1037.

- Zaliekas J, Munson JL. Complications of gallstones: the Mirizzi syndrome, gallstone ileus, gallstone pancreatitis, complications of "lost" gallstones. Surg Clin North Am. 2008 Dec. 88 (6):1345-68, x. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Elwood DR. Cholecystitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2008 Dec. 88 (6):1241-52, viii. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rothenberg RE, LaRaja RD, McCoy RE, Pryce EH. Elective cholecystectomy and carcinoma of the gallbladder. Am Surg. 1991 May. 57 (5):306-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- de Aretxabala XA, Roa IS, Burgos LA, Araya JC, Villaseca MA, Silva JA. Curative resection in potentially resectable tumours of the gallbladder. Eur J Surg. 1997 Jun. 163 (6):419-26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Roa I, Araya JC, Wistuba I, de Aretxabala X. [Gallbladder cancer: anatomic and anatomo-pathologic considerations]. Rev Med Chil. 1990 May. 118 (5):572-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Maker AV, Butte JM, Oxenberg J, Kuk D, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Is port site resection necessary in the surgical management of gallbladder cancer?. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Feb. 19 (2):409-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Miltenburg DM, Schaffer RL, Palit TK, Brandt ML. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children: is it better than open surgery?. Pediatr Endosurg Innov Techn. 2001 Mar. 5 (1):13-7.

- Curro G, Baccarani U, Adani G, Cucinotta E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with mild cirrhosis and symptomatic cholelithiasis. Transplant Proc. 2007 Jun. 39 (5):1471-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cucinotta E, Lazzara S, Melita G. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients. Surg Endosc. 2003 Dec. 17 (12):1958-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kuy S, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Outcomes following cholecystectomy in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Surgery. 2009 Aug. 146 (2):358-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Date RS, Kaushal M, Ramesh A. A review of the management of gallstone disease and its complications in pregnancy. Am J Surg. 2008 Oct. 196 (4):599-608. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Han HS, Yoon YS, Agarwal AK, Belli G, Itano O, Gumbs AA, et al. Laparoscopic Surgery for Gallbladder Cancer: An Expert Consensus Statement. Dig Surg. 2019. 36 (1):1-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Roa I, Araya JC, Wistuba I, Villaseca M, de Aretxabala X, Gómez A, et al. [Laparoscopic cholecystectomy makes difficult the analysis of gallbladder mucosa. Morphometric study]. Rev Med Chil. 1994 Sep. 122 (9):1015-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kiviluoto T, Sirén J, Luukkonen P, Kivilaakso E. Randomised trial of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for acute and gangrenous cholecystitis. Lancet. 1998 Jan 31. 351 (9099):321-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kwon YJ, Ahn BK, Park HK, Lee KS, Lee KG. What is the optimal time for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in gallbladder empyema?. Surg Endosc. 2013 Oct. 27 (10):3776-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dalley AF II, Agur AMR. Abdominal viscera. Moore's Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2023. 454-538.

- Nagral S. Anatomy relevant to cholecystectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2005 Jun. 1 (2):53-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Biliary system. Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 21st ed. St Louis: Elsevier; 2022. Chap 55.

- Michalowski K, Bornman PC, Krige JE, Gallagher PJ, Terblanche J. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in patients with complicated acute cholecystitis or fibrosis. Br J Surg. 1998 Jul. 85 (7):904-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Flum DR, Koepsell T, Heagerty P, Sinanan M, Dellinger EP. Common bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the use of intraoperative cholangiography: adverse outcome or preventable error?. Arch Surg. 2001 Nov. 136 (11):1287-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khera SY, Kostyal DA, Deshmukh N. A comparison of chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine skin preparation for surgical operations. Curr Surgery. 1999 Jul-Aug. 56 (6):341-3.

- MacFadyen BV Jr, Vecchio R, Ricardo AE, Mathis CR. Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The United States experience. Surg Endosc. 1998 Apr. 12 (4):315-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995 Jan. 180 (1):101-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fabiani P, Iovine L, Katkhouda N, Gugenheim J, Mouiel J. [Dissection of the Calot's triangle by the celioscopic approach]. Presse Med. 1993 Mar 27. 22 (11):535-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Branum G, Schmitt C, Baillie J, Suhocki P, Baker M, Davidoff A, et al. Management of major biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1993 May. 217 (5):532-40; discussion 540-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Flum DR, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L, Koepsell T. Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA. 2003 Apr 2. 289 (13):1639-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Metcalfe MS, Ong T, Bruening MH, Iswariah H, Wemyss-Holden SA, Maddern GJ. Is laparoscopic intraoperative cholangiogram a matter of routine?. Am J Surg. 2004 Apr. 187 (4):475-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nugent N, Doyle M, Mealy K. Low incidence of retained common bile duct stones using a selective policy of biliary imaging. Surgeon. 2005 Oct. 3 (5):352-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barkun JS, Fried GM, Barkun AN, Sigman HH, Hinchey EJ, Garzon J, et al. Cholecystectomy without operative cholangiography. Implications for common bile duct injury and retained common bile duct stones. Ann Surg. 1993 Sep. 218 (3):371-7; discussion 377-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Steiner CA, Bass EB, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Steinberg EP. Surgical rates and operative mortality for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Maryland. N Engl J Med. 1994 Feb 10. 330 (6):403-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Csikesz N, Ricciardi R, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Current status of surgical management of acute cholecystitis in the United States. World J Surg. 2008 Oct. 32 (10):2230-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Giger UF, Michel JM, Opitz I, Th Inderbitzin D, Kocher T, Krähenbühl L. Risk factors for perioperative complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: analysis of 22,953 consecutive cases from the Swiss Association of Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery database. J Am Coll Surg. 2006 Nov. 203(5):723-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang WT, Lee KT, Chuang SC, Wang SN, Kuo KK, Chen JS, et al. The impact of prophylactic antibiotics on postoperative infection complication in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2006 Jun. 191 (6):721-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tocchi A, Lepre L, Costa G, Liotta G, Mazzoni G, Maggiolini F. The need for antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2000 Jan. 135 (1):67-70; discussion 70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Higgins A, London J, Charland S, Ratzer E, Clark J, Haun W, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: are they necessary?. Arch Surg. 1999 Jun. 134 (6):611-3; discussion 614. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sanabria A, Dominguez LC, Valdivieso E, Gomez G. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Dec 8. 12:CD005265. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lau WY, Yuen WK, Chu KW, Chong KK, Li AK. Systemic antibiotic regimens for acute cholecystitis treated by early cholecystectomy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990 Jul. 60 (7):539-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- El-Dawlatly AA, Al-Dohayan A, Fadin A. Epidural anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy: case report and review of literature. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2007. 13(1):[Full Text].

- Tzovaras G, Fafoulakis F, Pratsas K, Georgopoulou S, Stamatiou G, Hatzitheofilou C. Spinal vs general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: interim analysis of a controlled randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2008 May. 143 (5):497-501. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gurusamy K, Junnarkar S, Farouk M, Davidson BR. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the safety and effectiveness of day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2008 Feb. 95 (2):161-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sultan AM, El Nakeeb A, Elshehawy T, Elhemmaly M, Elhanafy E, Atef E. Risk factors for conversion during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: retrospective analysis of ten years' experience at a single tertiary referral centre. Dig Surg. 2013. 30 (1):51-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Brunt LM, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, Strasberg SM, Aggarwal R, Asbun H, et al. Safe Cholecystectomy Multi-society Practice Guideline and State of the Art Consensus Conference on Prevention of Bile Duct Injury During Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2020 Jul. 272 (1):3-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Bansal VK, Misra MC, Agarwal AK, Agrawal JB, Agarwal PN, Aggarwal S, et al. SELSI Consensus Statement for Safe Cholecystectomy—Prevention and Management of Bile Duct Injury—Part A. Indian J Surg. 2021. 83:592-610. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Bansal VK, Misra MC, Agarwal AK, Agrawal JB, Agarwal PN, Aggarwal S, et al. SELSI Consensus Statement for Safe Cholecystectomy—Prevention and Management of Bile Duct Injury—Part B. Indian J Surg. 2021. 83:611-24. [Full Text].

- Hunter JG. Avoidance of bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1991 Jul. 162 (1):71-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Strasberg SM. Biliary injury in laparoscopic surgery: part 2. Changing the culture of cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2005 Oct. 201 (4):604-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yeh CN, Jan YY, Liu NJ, Yeh TS, Chen MF. Endo-GIA for ligation of dilated cystic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an alternative, novel, and easy method. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004 Jun. 14 (3):153-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Abbas IS. Overlapped-clipping, a new technique for ligation of a wide cystic duct in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005 Jul-Aug. 52 (64):1039-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nowzaradan Y, Meador J, Westmoreland J. Laparoscopic management of enlarged cystic duct. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992 Dec. 2 (4):323-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tonouchi H, Ohmori Y, Kobayashi M, Kusunoki M. Trocar site hernia. Arch Surg. 2004 Nov. 139 (11):1248-56. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Novitsky YW, Kercher KW, Czerniach DR, Kaban GK, Khera S, Gallagher-Dorval KA, et al. Advantages of mini-laparoscopic vs conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2005 Dec. 140 (12):1178-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yamazaki M, Yasuda H, Koda K. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review of methodology and outcomes. Surg Today. 2015 May. 45 (5):537-48. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kim MJ, Kim TS, Kim KH, An CH, Kim JS. Safety and feasibility of needlescopic grasper-assisted single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis: comparison with three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014 Aug. 24 (8):523-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sato N, Shibao K, Mori Y, Higure A, Yamaguchi K. Postoperative complications following single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a retrospective analysis in 360 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2015 Mar. 29 (3):708-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jategaonkar PA, Yadav SP. Prospective Observational Study of Single-Site Multiport Per-umbilical Laparoscopic Endosurgery versus Conventional Multiport Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Critical Appraisal of a Unique Umbilical Approach. Minim Invasive Surg. 2014. 2014:909321. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Breitenstein S, Nocito A, Puhan M, Held U, Weber M, Clavien PA. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy: outcome and cost analyses of a case-matched control study. Ann Surg. 2008 Jun. 247 (6):987-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buzad FA, Corne LM, Brown TC, Fagin RS, Hebert AE, Kaczmarek CA, et al. Single-site robotic cholecystectomy: efficiency and cost analysis. Int J Med Robot. 2013 Sep. 9 (3):365-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhou PH, Liu FL, Yao LQ, Qin XY. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003 Feb. 2 (1):117-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moore MJ, Bennett CL. The learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The Southern Surgeons Club. Am J Surg. 1995 Jul. 170 (1):55-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lien HH, Huang CC, Liu JS, Shi MY, Chen DF, Wang NY, et al. System approach to prevent common bile duct injury and enhance performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007 Jun. 17 (3):164-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Southern Surgeons Club. A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. N Engl J Med. 1991 Apr 18. 324 (16):1073-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Massarweh NN, Flum DR. Role of intraoperative cholangiography in avoiding bile duct injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 Apr. 204(4):656-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of fascial stay sutures.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Visualization of gallbladder after placement of table in reverse Trendelenburg position.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Advancement of 11-mm trocar under direct vision.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of two lateral 5-mm ports under direct vision.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. External view after port placement.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lateral grasper is used to retract fundus cephalad and retract adhesions.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medial grasper is applied to infundibulum.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medial grasper is used to retract infundibulum in caudolateral direction.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Critical view, with only cystic duct and cystic artery seen entering gallbladder.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Use of L-hook electrocautery to score anterior peritoneum.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Division of peritoneum along medial aspect.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Use of Endo Peanut to identify cystic structures.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Use of Maryland dissector to dissect cystic duct.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Use of Maryland dissector to dissect cystic artery.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Continued dissection of critical structures.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of clip at lower aspect of cystic artery.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of superior clips on cystic artery.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Transection of cystic artery with Endo Shears.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of clips on distal cystic duct.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of proximal clip on cystic duct.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. View of clipped cystic duct before transection.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Transection of cystic duct between clips with Endo Shears.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Use of hook to develop plane in areolar tissue between gallbladder and liver.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Use of traction and hook to remove gallbladder from gallbladder bed.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Side-to-side sweeping motion with electrocautery to remove gallbladder from gallbladder bed.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cauterization of any bleeding in gallbladder bed before complete division of gallbladder.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of gallbladder into endoscopic retrieval pouch.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Placement of gallbladder into endoscopic retrieval pouch and removal of instrument from pouch.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Irrigation and suction of gallbladder bed.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Removal of ports under direct vision.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Abdomen after skin closure.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. CT scan illustrating biloma.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Postcholecystectomy ERCP showing leak of contrast.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Postcholecystectomy ERCP.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ERCP-guided stent placement.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HIDA scan showing postcholecystectomy leak.

- Anatomy of biliary tree.

- Gallbladder anatomy. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons | OpenStax College, Anatomy & Physiology (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2425\_Gallbladder.jpg). Creative Commons BY 3.0 Deed (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Author

Danny A Sherwinter, MD Attending Surgeon, Department of Mimially Invasive Surgery and Bariatrics, Associate Program Director, Department of Surgery, Maimonides Medical Center; Director of Minimally Invasive and Bariatric Surgery, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) Center of Excellence

Danny A Sherwinter, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, Society of Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgeons

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Coauthor(s)

Stalin Ramakrishnan Subramanian, MD Resident Physician, Department of Medicine, Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Vinay K Kapoor, MBBS, MS, FRCSEd, FICS, FAMS Professor of Surgical Gastroenterology, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital (MGMCH), Jaipur, India

Vinay K Kapoor, MBBS, MS, FRCSEd, FICS, FAMS is a member of the following medical societies: Association of Surgeons of India, Indian Association of Surgical Gastroenterology, Indian Society of Gastroenterology, Medical Council of India, National Academy of Medical Sciences (India), Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Jerzy M Macura, MD Chief of Advanced Laparoscopic Surgery, Director of Bariatric Surgery, Maimonides Medical Center

Jerzy M Macura, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, American Society of Abdominal Surgeons, and Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.