Peptic Ulcer Disease: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Background

Peptic ulcer disease can involve the stomach or duodenum. Gastric and duodenal ulcers usually cannot be differentiated based on history alone, although some findings may be suggestive (see DDx). Epigastric pain is the most common symptom of both gastric and duodenal ulcers, characterized by a gnawing or burning sensation and that occurs after meals—classically, shortly after meals with gastric ulcers and 2-3 hours afterward with duodenal ulcers.

In uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease, the clinical findings are few and nonspecific. “Alarm features" that warrant prompt gastroenterology referral [1] include bleeding, anemia, early satiety, unexplained weight loss, progressive dysphagia or odynophagia, recurrent vomiting, and a family history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer. Patients with perforated peptic ulcer disease usually present with a sudden onset of severe, sharp abdominal pain. (See Presentation.)

In most patients with uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease, routine laboratory tests usually are not helpful; instead, documentation of peptic ulcer disease depends on radiographic and endoscopic confirmation. Testing for H pylori infection is essential in all patients with peptic ulcers. Rapid urease tests are considered the endoscopic diagnostic test of choice. Of the noninvasive tests, fecal antigen testing is more accurate than antibody testing and is less expensive than urea breath tests but either is reasonable. A fasting serum gastrin level should be obtained in certain cases to screen for Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. (See Workup.)

Upper GI endoscopy is the preferred diagnostic test in the evaluation of patients with suspected peptic ulcer disease. Endoscopy provides an opportunity to visualize the ulcer, to determine the presence and degree of active bleeding, and to attempt hemostasis by direct measures, if required. Perform endoscopy early in patients older than 45-50 years and in patients with associated so-called alarm features.

Most patients with peptic ulcer disease are treated successfully with cure of H pylori infection and/or avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), along with the appropriate use of antisecretory therapy. In the United States, the recommended primary therapy for H pylori infection is proton pump inhibitor (PPI)–based triple therapy. [1] These regimens result in a cure of infection and ulcer healing in approximately 85-90% of cases. [2] Ulcers can recur in the absence of successful H pylori eradication. (See Treatment.)

In patients with NSAID-associated peptic ulcers, discontinuation of NSAIDs is paramount, if it is clinically feasible. For patients who must continue with their NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) maintenance is recommended to prevent recurrences even after eradication of H pylori. [3, 4] Prophylactic regimens that have been shown to dramatically reduce the risk of NSAID-induced gastric and duodenal ulcers include the use of a prostaglandin analog or a PPI. Maintenance therapy with antisecretory medications (eg, H2 blockers, PPIs) for 1 year is indicated in high-risk patients. (See Medication.)

The indications for urgent surgery include failure to achieve hemostasis endoscopically, recurrent bleeding despite endoscopic attempts at achieving hemostasis (many advocate surgery after two failed endoscopic attempts), and perforation.

Patients with gastric ulcers are also at risk of developing gastric malignancy.

Anatomy

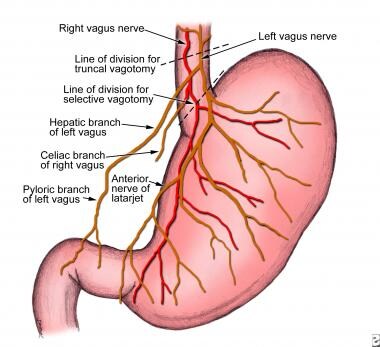

Because many surgical procedures for peptic ulcer disease entail some type of vagotomy, a discussion concerning the vagal innervation of the abdominal viscera is appropriate (see image below). The left (anterior) and the right (posterior) branches of the vagus nerve descend along either side of the distal esophagus. As they enter the lower thoracic cavity, they can communicate with each other through several cross-branches that comprise the esophageal plexus. However, below this plexus, the two vagal trunks again become separate and distinct before the anterior trunk branches to form the hepatic, pyloric, and anterior gastric (also termed the anterior nerve of Latarjet) branches. The posterior trunk branches to form the posterior gastric branch (also termed the posterior nerve of Latarjet) and the celiac branch.

The parietal cell mass of the stomach is segmentally innervated by the terminal branches from each of the anterior and posterior gastric branches. These terminal branches are divided during highly selective vagotomy. The gallbladder is innervated from efferent branches of the hepatic division of the anterior trunk. Consequently, transection of the anterior vagus trunk (performed during truncal vagotomy) can result in a dilated gallbladder with inhibited contractility and subsequent cholelithiasis. The celiac branch of the posterior vagus innervates the entire midgut (with the exception of the gallbladder). Thus, division of the posterior trunk during truncal vagotomy may contribute to postoperative ileus.

Peptic ulcer disease. Vagal innervation of the stomach.

Pathophysiology

Peptic ulcers are defects in the gastric or duodenal mucosa that extend through the muscularis mucosa. The epithelial cells of the stomach and duodenum secrete mucus in response to irritation of the epithelial lining and as a result of cholinergic stimulation. The superficial portion of the gastric and duodenal mucosa exists in the form of a gel layer, which is impermeable to acid and pepsin. Other gastric and duodenal cells secrete bicarbonate, which aids in buffering acid that lies near the mucosa. Prostaglandins of the E type (PGE) have an important protective role, because PGE increases the production of both bicarbonate and the mucous layer.

In the event of acid and pepsin entering the epithelial cells, additional mechanisms are in place to reduce injury. Within the epithelial cells, ion pumps in the basolateral cell membrane help to regulate intracellular pH by removing excess hydrogen ions. Through the process of restitution, healthy cells migrate to the site of injury. Mucosal blood flow removes acid that diffuses through the injured mucosa and provides bicarbonate to the surface epithelial cells.

Under normal conditions, a physiologic balance exists between gastric acid secretion and gastroduodenal mucosal defense. Mucosal injury and, thus, peptic ulcer occur when the balance between the aggressive factors and the defensive mechanisms is disrupted. Aggressive factors, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), H pylori infection, alcohol, bile salts, acid, and pepsin, can alter the mucosal defense by allowing the back diffusion of hydrogen ions and subsequent epithelial cell injury. The defensive mechanisms include tight intercellular junctions, mucus, bicarbonate, mucosal blood flow, cellular restitution, and epithelial renewal.

The gram-negative spirochete H pylori was first linked to gastritis in 1983. Since then, further study of H pylori has revealed that it is a major part of the triad, which includes acid and pepsin, that contributes to primary peptic ulcer disease. The unique microbiologic characteristics of this organism, such as urease production, allows it to alkalinize its microenvironment and survive for years in the hostile acidic environment of the stomach, where it causes mucosal inflammation and, in some individuals, worsens the severity of peptic ulcer disease.

When H pylori colonizes the gastric mucosa, inflammation usually results. The causal association between H pylori gastritis and duodenal ulceration is now well established in the adult and pediatric literature. In patients infected with H pylori, high levels of gastrin and pepsinogen and reduced levels of somatostatin have been measured. In infected patients, exposure of the duodenum to acid is increased. Virulence factors produced by H pylori, including urease, catalase, vacuolating cytotoxin, and lipopolysaccharide, are well described.

Most patients with duodenal ulcers have impaired duodenal bicarbonate secretion, which has also proven to be caused by H pylori because its eradication reverses the defect. [5] The combination of increased gastric acid secretion and reduced duodenal bicarbonate secretion lowers the pH in the duodenum, which promotes the development of gastric metaplasia (ie, the presence of gastric epithelium in the first portion of the duodenum). H pylori infection in areas of gastric metaplasia induces duodenitis and enhances the susceptibility to acid injury, thereby predisposing to duodenal ulcers. Duodenal colonization by H pylori was found to be a highly significant predictor of subsequent development of duodenal ulcers in one study that followed 181 patients with endoscopy-negative, nonulcer dyspepsia. [6]

Etiology

Peptic ulcer disease may be due to any of the following:

- H pylori infection

- Drugs

- Lifestyle factors

- Severe physiologic stress

- Hypersecretory states (uncommon)

- Genetic factors

H pylori infection

H pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use account for most cases of peptic ulcer disease. The rate of H pylori infection for duodenal ulcers in the United States is less than 75% for patients who do not use NSAIDs. Excluding patients who used NSAIDs, 61% of duodenal ulcers and 63% of gastric ulcers were positive for H pylori in one study. These rates were lower in whites than in nonwhites. Prevalence of H pylori infection in complicated ulcers (ie, bleeding, perforation) is significantly lower than that found in uncomplicated ulcer disease.

Drugs

NSAID use is a common cause of peptic ulcer disease. These drugs disrupt the mucosal permeability barrier, rendering the mucosa vulnerable to injury. As many as 30% of adults taking NSAIDs have GI adverse effects. Factors associated with an increased risk of duodenal ulcers in the setting of NSAID use include history of previous peptic ulcer disease, older age, female sex, high doses or combinations of NSAIDs, long-term NSAID use, concomitant use of anticoagulants, and severe comorbid illnesses.

A long-term prospective study found that patients with arthritis who were older than 65 years who regularly took low-dose aspirin were at an increased risk for dyspepsia severe enough to necessitate the discontinuation of NSAIDs. [7] This suggests that better management of NSAID use should be discussed with older patients in order to reduce NSAID-associated upper GI events.

A UK retrospective study of patients newly initiated on low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events identified risk factors for uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease in these patients that included the following [8] :

- Previous history of peptic ulcer disease

- Current use of NSAIDs, oral steroid agents, or acid suppressive agents

- Tobacco use

- Stress

- Depression

- Anemia

- Social deprivation (comprises four census variables used in the Townsend deprivation index [9] : households that lack a car, are overcrowded, not owner-occupied, and have unemployed persons)

Although the idea was initially controversial, most evidence now supports the assertion that H pylori and NSAIDs are synergistic with respect to the development of peptic ulcer disease. A meta-analysis found that H pylori eradication in NSAID-naive users before the initiation of NSAIDs was associated with a decrease in peptic ulcers. [10]

Although the prevalence of NSAID gastropathy in children is unknown, it seems to be increasing, especially in children with chronic arthritis treated with NSAIDs. Case reports have demonstrated gastric ulceration from low-dose ibuprofen in children, even after just 1 or 2 doses. [11]

Corticosteroids alone do not increase the risk for peptic ulcer disease; however, they can potentiate ulcer risk in patients who use NSAIDs concurrently.

The risk of upper GI tract bleeding may be increased in users of the diuretic spironolactone [12] or serotonin reuptake inhibitors with moderate to high affinity for serotonin transporter. [13]

Lifestyle factors

Evidence that tobacco use is a risk factor for duodenal ulcers is not conclusive. Support for a pathogenic role for smoking comes from the finding that smoking may accelerate gastric emptying and decrease pancreatic bicarbonate production. However, studies have produced contradictory findings. In one prospective study of more than 47,000 men with duodenal ulcers, smoking did not emerge as a risk factor. [14] However, smoking in the setting of H pylori infection may increase the risk of relapse of peptic ulcer disease. [15] Smoking is harmful to the gastroduodenal mucosa, and H pylori infiltration is denser in the gastric antrum of smokers. [16]

Ethanol is known to cause gastric mucosal irritation and nonspecific gastritis. Evidence that consumption of alcohol is a risk factor for duodenal ulcer is inconclusive. A prospective study of more than 47,000 men with duodenal ulcer did not find an association between alcohol intake and duodenal ulcer. [14]

Little evidence suggests that caffeine intake is associated with an increased risk of duodenal ulcers.

Severe physiologic stress

Stressful conditions that may cause peptic ulcer disease include burns, central nervous system (CNS) trauma, surgery, and severe medical illness. Serious systemic illness, sepsis, hypotension, respiratory failure, and multiple traumatic injuries increase the risk for secondary (stress) ulceration.

Cushing ulcers are associated with a brain tumor or injury and typically are single, deep ulcers that are prone to perforation. They are associated with high gastric acid output and are located in the duodenum or stomach. Extensive burns are associated with Curling ulcers.

Stress ulceration and upper-gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage are complications that are increasingly encountered in critically ill children in the intensive care setting. Severe illness and a decreased gastric pH are related to an increased risk of gastric ulceration and hemorrhage.

Hypersecretory states (uncommon)

The following are among hypersecretory states that may, uncommonly, cause peptic ulcer disease:

- Gastrinoma (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome) or multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN-I)

- Antral G cell hyperplasia

- Systemic mastocytosis

- Basophilic leukemias

- Cystic fibrosis

- Short bowel syndrome

- Hyperparathyroidism

Physiologic factors

In up to one third of patients with duodenal ulcers, basal acid output (BAO) and maximal acid output (MAO) are increased. In one study, increased BAO was associated with an odds ratio [OR] of up to 3.5, and increased MAO was associated with an OR of up to 7 for the development of duodenal ulcers. Individuals at especially high risk are those with a BAO greater than 15 mEq/h. The increased BAO may reflect the fact that in a significant proportion of patients with duodenal ulcers, the parietal cell mass is increased to nearly twice that of the reference range. [17]

In addition to the increased gastric and duodenal acidity observed in some patients with duodenal ulcers, accelerated gastric emptying is often present. This acceleration leads to a high acid load delivered to the first part of the duodenum, where 95% of all duodenal ulcers are located. Acidification of the duodenum leads to gastric metaplasia, which indicates replacement of duodenal villous cells with cells that share morphologic and secretory characteristics of the gastric epithelium. Gastric metaplasia may create an environment that is well suited to colonization by H pylori.

Seasonal changes and climate extremes may also affect gastric mucosa and cause damage to the gastric mucosa and its barrier function. [18] In extreme cold climate, Yuan et al noted significantly lower expression of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) as well as decreased mucosal thickness in the gastric antrum of patients with peptic ulcer disease who were at high risk of bleeding compared to those at low risk of bleeding.

Moreover, compared to extreme hot climate, extreme cold climate was associated with significantly lower levels of occludin, HSP70, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), but no statistically significant differences in these protein expression levels were found between patients at high and low risk of bleeding. [18] The investigators also did not note any significant differences found in the rates of H pylori infection and pH levels of gastric juices between patients at high bleeding risk and those at low bleeding risk. [18]

Genetics

More than 20% of patients have a family history of duodenal ulcers, compared with only 5-10% in the control groups. In addition, weak associations have been observed between duodenal ulcers and blood type O. Furthermore, patients who do not secrete ABO antigens in their saliva and gastric juices are known to be at higher risk. The reason for these apparent genetic associations is unclear.

A rare genetic association exists between familial hyperpepsinogenemia type I (a genetic phenotype leading to enhanced secretion of pepsin) and duodenal ulcers. However, H pylori can increase pepsin secretion, and a retrospective analysis of the sera of one family studied before the discovery of H pylori revealed that their high pepsin levels were more likely related to H pylori infection.

Additional etiologic factors

Any of the following may be associated with peptic ulcer disease:

- Allergic gastritis and eosinophilic gastritis

- Uremic gastropathy

- Henoch-Schönlein gastritis

- Corrosive gastropathy

- Bile gastropathy

- Autoimmune disease

- Phlegmonous gastritis and emphysematous gastritis

- Other infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, Helicobacter heilmannii, herpes simplex, influenza, syphilis, Candida albicans, histoplasmosis, mucormycosis, and anisakiasis

- Chemotherapeutic agents, such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), methotrexate (MTX), and cyclophosphamide

- Local radiation resulting in mucosal damage, which may lead to the development of duodenal ulcers

- Use of crack cocaine, which causes localized vasoconstriction, resulting in reduced blood flow and possibly leading to mucosal damage

Epidemiology

The global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease, along with the associated rates of hospitalizations and mortality, have been in decline over the past couple of decades, attributed in part to the complex changes in the risk factors for peptic ulcer disease, including reductions in the prevalence of H pylori infection, the widespread use of antisecretory agents and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and an aging population. [19]

United States statistics

In the United States, peptic ulcer disease affects approximately 4.6 million people annually, with an estimated 10% of the US population having evidence of a duodenal ulcer at some time. [20] H pylori infection accounts for 90% of duodenal ulcers and 70%-90% of gastric ulcers. [21] The proportion of people with H pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease increases steadily with age.

Overall, the incidence of duodenal ulcers has been decreasing over the past 3-4 decades. Although the rate of simple gastric ulcer is in decline, the incidence of complicated gastric ulcer and hospitalization has remained stable, partly due to the concomitant use of aspirin in an aging population.

The prevalence of peptic ulcer disease has shifted from predominance in males to similar occurrences in males and females. The lifetime prevalence is approximately 11%-14% in men and 8-11% in women. [20] Age trends for ulcer occurrence reveal declining rates in younger men, particularly for duodenal ulcer, and increasing rates in older women.

In a systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane library, the annual incidence rates of peptic ulcer disease were found to be 0.10-0.19% for physician-diagnosed peptic ulcer disease and 0.03-0.17% when based on hospitalization data. [22] The 1-year prevalence based on physician diagnosis was 0.12-1.50% and that based on hospitalization data was 0.10-0.19%. The majority of studies reported a decrease in the incidence or prevalence of peptic ulcer disease over time. [22]

International statistics

The frequency of peptic ulcer disease in other countries is variable and is determined primarily by association with the major causes of peptic ulcer disease: H pylori and NSAIDs. [23] A 2018 systematic MEDLINE and PubMed review found Spain had the highest annual incidence of all peptic ulcer disease (141.8/100,000 persons), whereas the United Kingdom had the lowest (23.9/100,000 persons). [24] When perforated peptic ulcer disease was assessed, South Korea had the highest annual incidence (4.4/100,000 persons) and the United Kingdom, again, had the lowest (2.2/100,000 persons). [24]

Prognosis

When the underlying cause of peptic ulcer disease is addressed, the prognosis is excellent. Most patients are treated successfully with the eradication of H pylori infection, avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), and the appropriate use of antisecretory therapy. Eradication of H pylori infection changes the natural history of the disease, with a decrease in the ulcer recurrence rate from 60% to 90% to approximately 10% to 20%. However, this is a higher recurrence rate than previously reported, suggesting an increased number of ulcers not caused by H pylori infection.

With regard to NSAID-related ulcers, the incidence of perforation is approximately 0.3% per patient year, and the incidence of obstruction is approximately 0.1% per patient year. Combining both duodenal ulcers and gastric ulcers, the rate of any complication in all age groups combined is approximately 1-2% per ulcer per year.

The mortality rate for peptic ulcer disease, which has decreased modestly in the last few decades, is approximately 1 death per 100,000 cases. If one considers all patients with duodenal ulcers, the mortality rate due to ulcer hemorrhage is approximately 5%. [20] Over the last 20 years, the mortality rate in the setting of ulcer hemorrhage has not changed appreciably despite the advent of histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). However, evidence from meta-analyses and other studies has shown a decreased mortality rate from bleeding peptic ulcers when intravenous PPIs are used after successful endoscopic therapy. [25, 26, 27, 28]

Emergency operations for peptic ulcer perforation carry a mortality risk of 6-30%. [29, 30] Factors associated with higher mortality in this setting include the following:

- Shock at the time of admission

- Renal insufficiency

- Delaying the initiation of surgery for more than 12 hours after presentation

- Concurrent medical illness (eg, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus)

- Age older than 70 years

- Cirrhosis

- Immunocompromised state

- Location of ulcer (mortality associated with perforated gastric ulcer is twice that associated with perforated duodenal ulcer)

In a retrospective population-based study (2001-2014) that evaluated long-term mortality in 234 patients who underwent surgery for perforated peptic ulcer, mortality was 15.2% at 30 days, 19.2% at 90 days, 22.6% at 1 year, and 24.8% at 2 years. [31] When the 30-day mortality data were excluded, 36% of patients died during a median follow-up of 57 months. Independent factors associated with an increased risk of long-term mortality included age older than 60 years and the presence of comorbidities such as active malignancy, hypoalbuminemia, pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, and severe postoperative complications during the initial stay. [31]

Patient Education

Patients with peptic ulcer disease should be warned about known or potentially injurious drugs and agents. Some examples are as follows:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Aspirin

- Alcohol

- Tobacco

- Caffeine (eg, coffee, tea, colas)

Obesity has been shown to have an association with peptic ulcer disease, and patients should be counseled regarding benefits of weight loss. Stress reduction counseling might be helpful in individual cases but is not needed routinely.

For patient education resources, see Digestive Disorders Center as well as Peptic Ulcer, Heartburn, and GERD and Heartburn Medications.

- [Guideline] Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug. 102(8):1808-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Javid G, Zargar SA, U-Saif R, et al. Comparison of p.o. or i.v. proton pump inhibitors on 72-h intragastric pH in bleeding peptic ulcer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Jul. 24(7):1236-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jun 27. 346(26):2033-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, et al. Lansoprazole reduces ulcer relapse after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users--a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Oct 15. 18(8):829-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, Yung MY, Lau JY, Chiu PW. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jan. 105(1):84-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pietroiusti A, Luzzi I, Gomez MJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori duodenal colonization is a strong risk factor for the development of duodenal ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Apr 1. 21(7):909-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Laine L, Curtis SP, Cryer B, Kaur A, Cannon CP. Risk factors for NSAID-associated upper GI clinical events in a long-term prospective study of 34 701 arthritis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Nov. 32(10):1240-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ruigomez A, Johansson S, Nagy P, Martin-Perez M, Rodriguez LA. Risk of uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease in a cohort of new users of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 10. 14:205. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- ReStore, National Centre for Research Methods. Geographical referencing learning resources: Townsend deprivation index. Available at https://www.restore.ac.uk/geo-refer/36229dtuks00y19810000.php. Accessed: December 20, 2018.

- Vergara M, Catalan M, Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Meta-analysis: role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in the prevention of peptic ulcer in NSAID users. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Jun 15. 21(12):1411-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Berezin SH, Bostwick HE, Halata MS, Feerick J, Newman LJ, Medow MS. Gastrointestinal bleeding in children following ingestion of low-dose ibuprofen. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007 Apr. 44(4):506-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gulmez SE, Lassen AT, Aalykke C, et al. Spironolactone use and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a population-based case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008 Aug. 66(2):294-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lewis JD, Strom BL, Localio AR, et al. Moderate and high affinity serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal toxicity. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008 Apr. 17(4):328-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Willett WC. A prospective study of alcohol, smoking, caffeine, and the risk of duodenal ulcer in men. Epidemiology. 1997 Jul. 8(4):420-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sonnenberg A, Muller-Lissner SA, Vogel E, et al. Predictors of duodenal ulcer healing and relapse. Gastroenterology. 1981 Dec. 81(6):1061-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Koivisto TT, Voutilainen ME, Farkkila MA. Effect of smoking on gastric histology in Helicobacter pylori-positive gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008. 43(10):1177-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schubert ML, Peura DA. Control of gastric acid secretion in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jun. 134(7):1842-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yuan XG, Xie C, Chen J, Xie Y, Zhang KH, Lu NH. Seasonal changes in gastric mucosal factors associated with peptic ulcer bleeding. Exp Ther Med. 2015 Jan. 9(1):125-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017 Aug 5. 390(10094):613-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peptic ulcer. OMICS International. Available at https://www.omicsonline.org/united-states/peptic-ulcer-peer-reviewed-pdf-ppt-articles/. Accessed: August 1, 2019.

- Malik TF, Gnanapandithan K, Singh K. Peptic ulcer disease. StatPearls [Internet]. 2021 Jan. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sung JJ, Kuipers EJ, El-Serag HB. Systematic review: the global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 May 1. 29 (9):938-46. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cai S, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Masso-Gonzalez EL, Hernandez-Diaz S. Uncomplicated peptic ulcer in the UK: trends from 1997 to 2005. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Nov 15. 30(10):1039-48. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Azhari H, Underwood F, King J, et al. The global incidence of peptic ulcer disease and its complications at the turn of the 21st century: a systematic review. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018 Feb. 1(suppl_2):61-2. [Full Text].

- Leontiadis GI, Sreedharan A, Dorward S, et al. Systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Health Technol Assess. 2007 Dec. 11(51):iii-iv, 1-164. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bardou M, Toubouti Y, Benhaberou-Brun D, Rahme E, Barkun AN. High dose proton pump inhibition decrease both re-bleeding and mortality in high-risk patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2003. 123(suppl 1):A625.

- Bardou M, Youssef M, Toubouti Y, et al. Newer endoscopic therapies decrease both re-bleeding and mortality in high risk patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding: a series of meta-analyses [abstract]. Gastroenterology. 2003. 123:A239.

- Gisbert JP, Pajares R, Pajares JM. Evolution of Helicobacter pylori therapy from a meta-analytical perspective. Helicobacter. 2007 Nov. 12 suppl 2:50-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Svanes C, Lie RT, Svanes K, Lie SA, Soreide O. Adverse effects of delayed treatment for perforated peptic ulcer. Ann Surg. 1994 Aug. 220(2):168-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Sengupta TK, Prakash G, Ray S, Kar M. Surgical management of peptic perforation in a tertiary care center: a retrospective study. Niger Med J. 2020 Nov-Dec. 61(6):328-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Thorsen K, Soreide JA, Soreide K. Long-term mortality in patients operated for perforated peptic ulcer: factors limiting longevity are dominated by older age, comorbidity burden and severe postoperative complications. World J Surg. 2017 Feb. 41(2):410-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hung KW, Knotts RM, Faye AS, et al. Factors associated with adherence to Helicobacter pylori testing during hospitalization for bleeding peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 May. 18(5):1091-1098.e1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb. 112(2):212-39. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Early DS, Lightdale JR, Vargo JJ 2nd, et al, for the ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Guidelines for sedation and anesthesia in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Feb. 87(2):327-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC. Peptic ulcer disease. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Oct 1. 76(7):1005-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, Moayyedi P. What is the prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with dyspepsia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Oct. 8(10):830-7, 837.e1-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zullo A, Hassan C, Campo SM, Morini S. Bleeding peptic ulcer in the elderly: risk factors and prevention strategies. Drugs Aging. 2007. 24(10):815-28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Udd M, Miettinen P, Palmu A, et al. Analysis of the risk factors and their combinations in acute gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding: a case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007 Dec. 42(12):1395-403. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jensen DM, Eklund S, Persson T, et al. Reassessment of rebleeding risk of Forrest IB (oozing) peptic ulcer bleeding in a large international randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Mar. 112(3):441-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Wang HM, Hsu PI, Lo GH, et al. Comparison of hemostatic efficacy for argon plasma coagulation and distilled water injection in treating high-risk bleeding ulcers. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009 Nov-Dec. 43(10):941-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khodadoostan M, Karami-Horestani M, Shavakhi A, Sebghatollahi V. Endoscopic treatment for high-risk bleeding peptic ulcers: A randomized, controlled trial of epinephrine alone with epinephrine plus fresh frozen plasma. J Res Med Sci. 2016. 21:135. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Larssen L, Moger T, Bjornbeth BA, Lygren I, Klow NE. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of bleeding duodenal ulcers: a 5.5-year retrospective study of treatment and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008. 43(2):217-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Travis AC, Wasan SK, Saltzman JR. Model to predict rebleeding following endoscopic therapy for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Oct. 23(10):1505-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Elmunzer BJ, Young SD, Inadomi JM, Schoenfeld P, Laine L. Systematic review of the predictors of recurrent hemorrhage after endoscopic hemostatic therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Oct. 103(10):2625-32; quiz 2633. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chiu PW, Ng EK, Cheung FK, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers after therapeutic endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Mar. 7(3):311-6; quiz 253. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kikkawa A, Iwakiri R, Ootani H, et al. Prevention of the rehaemorrhage of bleeding peptic ulcers: effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication and acid suppression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Jun. 21 Suppl 2:79-84. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Feu F, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for the prevention of peptic ulcer rebleeding. Helicobacter. 2007 Aug. 12(4):279-86. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Boparai V, Rajagopalan J, Triadafilopoulos G. Guide to the use of proton pump inhibitors in adult patients. Drugs. 2008. 68(7):925-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall JK, for the Nonvariceal Upper GI Bleeding Consensus Conference Group. Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Nov 18. 139(10):843-57. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cote GA, Howden CW. Potential adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008 Jun. 10(3):208-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Laine L, Shah A, Bemanian S. Intragastric pH with oral vs intravenous bolus plus infusion proton-pump inhibitor therapy in patients with bleeding ulcers. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jun. 134(7):1836-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chan WH, Khin LW, Chung YF, Goh YC, Ong HS, Wong WK. Randomized controlled trial of standard versus high-dose intravenous omeprazole after endoscopic therapy in high-risk patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Br J Surg. 2011 May. 98(5):640-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Focareta R, et al. High- versus low-dose proton pump inhibitors after endoscopic hemostasis in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a multicentre, randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Dec. 103(12):3011-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sari YS, Can D, Tunali V, Sahin O, Koc O, Bender O. H pylori: treatment for the patient only or the whole family?. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Feb 28. 14(8):1244-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Konno M, Yokota S, Suga T, Takahashi M, Sato K, Fujii N. Predominance of mother-to-child transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection detected by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting analysis in Japanese families. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008 Nov. 27(11):999-1003. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Singh V, Mishra S, Maurya P, et al. Drug resistance pattern and clonality in H. pylori strains. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009 Mar 1. 3(2):130-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ram M R, Teh X, Rajakumar T, et al. Polymorphisms in the host CYP2C19 gene and antibiotic-resistance attributes of Helicobacter pylori isolates influence the outcome of triple therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019 Jan 1. 74(1):11-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM, for the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Mar. 104(3):728-38. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chan FK, Hung LC, Suen BY, et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in reducing the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2002 Dec 26. 347(26):2104-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yang M, He M, Zhao M, et al. Proton pump inhibitors for preventing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced gastrointestinal toxicity: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017 Jun. 33(6):973-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chan FK, Ching JY, Hung LC, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to prevent recurrent ulcer bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jan 20. 352(3):238-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lai KC, Chu KM, Hui WM, et al. Esomeprazole with aspirin versus clopidogrel for prevention of recurrent gastrointestinal ulcer complications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jul. 4(7):860-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hsu PI, Lai KH, Liu CP. Esomeprazole with clopidogrel reduces peptic ulcer recurrence, compared with clopidogrel alone, in patients with atherosclerosis. Gastroenterology. 2011 Mar. 140(3):791-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Talley NJ, Vakil N, for the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Oct. 100(10):2324-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tajima A, Koizumi K, Suzuki K, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and recurrent bleeding in peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Dec. 23 suppl 2:S237-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McConnell DB, Baba GC, Deveney CW. Changes in surgical treatment of peptic ulcer disease within a veterans hospital in the 1970s and the 1980s. Arch Surg. 1989 Oct. 124(10):1164-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Cosme A, et al, for the H. pylori Study Group of the Asociacion Espanola de Gastroenterologia (Spanish Gastroenterology Association). Long-term follow-up of 1,000 patients cured of Helicobacter pylori infection following an episode of peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug. 107(8):1197-204. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Tarasconi A, Coccolini F, Biffl WL, et al. Perforated and bleeding peptic ulcer: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020. 15:3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Berne TV, Donovan AJ. Nonoperative treatment of perforated duodenal ulcer. Arch Surg. 1989 Jul. 124(7):830-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Donovan AJ, Berne TV, Donovan JA. Perforated duodenal ulcer: an alternative therapeutic plan. Arch Surg. 1998 Nov. 133(11):1166-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wangensteen OH. Non-operative treatment of localized perforations of the duodenum. Proc Minn Acad Med. 1935. 18:477-80.

- Strand DS, Kim D, Peura DA. 25 years of proton pump inhibitors: a comprehensive review. Gut Liver. 2017 Jan 15. 11(1):27-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kajihara Y, Shimoyama T, Mizuki I. Analysis of the cost-effectiveness of using vonoprazan-amoxicillin-clarithromycin triple therapy for first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb. 52(2):238-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ng JC, Yeomans ND. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in low dose aspirin users: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med J Aust. 2018 Sep 1. 209(7):306-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mirabella A, Fiorentini T, Tutino R, et al. Laparoscopy is an available alternative to open surgery in the treatment of perforated peptic ulcers: a retrospective multicenter study. BMC Surg. 2018 Sep 25. 18(1):78. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Havens JM, Castillo-Angeles M, Nitzschke SL, Salim A. Disparities in peptic ulcer disease: A nationwide study. Am J Surg. 2018 Dec. 216(6):1127-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Satoh K, Yoshino J, Akamatsu T, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2015. J Gastroenterol. 2016 Mar. 51(3):177-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, Henderson C, Howden CW, Metz DC. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011. 84(2):102-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sonnenberg A. Temporal trends and geographical variations of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995. 9 suppl 2:3-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mohamed WA, Schaalan MF, Ramadan B. The expression profiling of circulating miR-204, miR-182, and lncRNA H19 as novel potential biomarkers for the progression of peptic ulcer to gastric cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2019 Aug. 120(8):13464-77. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sanaii A, Shirzad H, Haghighian M, et al. Role of Th22 cells in Helicobacter pylori-related gastritis and peptic ulcer diseases. Mol Biol Rep. 2019 Dec. 46(6):5703-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Chief Editor

Philip O Katz, MD, FACP, FACG Chairman, Division of Gastroenterology, Albert Einstein Medical Center; Clinical Professor of Medicine, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University

Philip O Katz, MD, FACP, FACG is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Medtronic

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Torax medical: pfizer consumer, .

Acknowledgements

Faisal Aziz, MD Assistant Professor of Surgery, Divsion of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Department of Surgery, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine

Faisal Aziz, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons and American Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Simmy Bank, MD Chair, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Long Island Jewish Hospital, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Jeffrey Glenn Bowman, MD, MS Consulting Staff, Highfield MRI

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Carmen Cuffari, MD Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology/Nutrition, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Carmen Cuffari, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Brian James Daley, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCP, CNSC Professor and Program Director, Department of Surgery, Chief, Division of Trauma and Critical Care, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Medicine

Brian James Daley, MD, MBA, FACS, FCCP, CNSC is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, Association for Academic Surgery, Association for Surgical Education, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, Shock Society, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Southeastern Surgical Congress, and Tennessee Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Shane M Devlin, MD, FRCP(C) Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Peter Lougheed Center, University of Calgary, Canada

Shane M Devlin, MD, FRCP(C) is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, Canadian Association of Gastroenterology, Canadian Medical Association, and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Steven C Dronen, MD, FAAEM Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, LeConte Medical Center

Steven C Dronen, MD, FAAEM is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

George T Fantry, MD Associate Professor of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Maryland School of Medicine

George T Fantry, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology and American Gastroenterological Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

John Geibel, MD, DSc, MA Vice Chair and Professor, Department of Surgery, Section of Gastrointestinal Medicine, and Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale University School of Medicine; Director, Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Yale-New Haven Hospital

John Geibel, MD, DSc, MA is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, American Physiological Society, American Society of Nephrology, Association for Academic Surgery, International Society of Nephrology, New York Academy of Sciences, and Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: AMGEN Royalty Consulting; Ardelyx Ownership interest Board membership

David Greenwald, MD Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Fellowship Program Director, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

David Greenwald, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Harsh Grewal, MD, FACS, FAAP Clinical Professor of Surgery, Temple University School of Medicine; Chief, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Cooper University Hospital

Harsh Grewal, MD, FACS, FAAP is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Surgeons, American Pediatric Surgical Association, Association for Surgical Education, Children's Oncology Group, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, International Pediatric Endosurgery Group, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, and SouthwesternSurgical Congress

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Eugene Hardin, MD, FAAEM, FACEP Former Chair and Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science; Former Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Martin Luther King Jr/Drew Medical Center

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Andre Hebra, MD Chief, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Professor of Surgery and Pediatrics, Medical University of South Carolina College of Medicine; Surgeon-in-Chief, Medical University of South Carolina Children's Hospital

Andre Hebra, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Pediatric Surgical Association, Children's Oncology Group, Florida Medical Association, International Pediatric Endosurgery Group, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons,South Carolina Medical Association, Southeastern Surgical Congress, and Southern Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Juda Zvi Jona MD, FAAP(s), FACS, EUPSA, Clinical Professor of Surgery, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine; Clinical Professor of Surgery, Northwestern University, The Feinberg School of Medicine; Attending Senior Surgeon, Director of Pediatric Surgery Service, Surgical Executive Committee, Sparrow Hospital

Juda Zvi Jona is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Bronchoesophagological Association, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Pediatric Surgical Association, Association for Academic Surgery, British Association of Paediatric Surgeons, Central Surgical Association, Children's Oncology Group, and International Pediatric Endosurgery Group

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Daryl Lau, MD, MPH, MSc, FRCP(C) Director of Translational Liver Research, Liver Center, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Daryl Lau, MD, MPH, MSc, FRCP(C) is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and American Gastroenterological Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Tri H Le, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center

Tri H Le, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Terence David Lewis, MBBS, FRACP, FRCPC, FACP Program Director, Internal Medicine Residency, & Assistant Chairman, Associate Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Loma Linda University Medical Center

Terence David Lewis, MBBS, FRACP, FRCPC, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, American Medical Association, California Medical Association, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, and Sigma Xi

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

B UK Li, MD Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Director, Pediatric Fellowships and Gastroenterology Fellowship, Medical Director, Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Cyclic Vomiting Program, Medical College of Wisconsin; Attending Gastroenterologist, Children's Hospital of Wisconsin

B UK Li, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Gastroenterological Association, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chris A Liacouras MD, Director of Pediatric Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Chris A Liacouras is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Wendi S Miller, MD Resident Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine

Wendi S Miller, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, and Southern Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Robert K Minkes, MD, PhD Professor of Surgery, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Southwestern Medical School; Medical Director and Chief of Surgical Services, Children's Medical Center of Dallas-Legacy Campus

Robert K Minkes, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Pediatric Surgical Association, and Phi Beta Kappa

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Waqar A Qureshi, MD Associate Professor of Medicine, Chief of Endoscopy, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Baylor College of Medicine and Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Waqar A Qureshi, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Erick F Rivas, MD, PT Resident Physician, Department of Surgery, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine

Erick F Rivas, MD, PT is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Ameesh Shah, MD Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Children's Memorial Hospital

Ameesh Shah, MD is a member of the following medical societies: North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Philip Shayne MD, Associate Professor, Program Director and Vice Chair for Education, Department of Emergency Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine

Philip Shayne is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Sanjeeb Shrestha, MD Consulting Staff, Division of Gastroenterology, Gastroenterology Care Consultants

Sanjeeb Shrestha, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, and American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mutaz I Sultan, MBChB Makassed Hospital, Israel

Mutaz I Sultan, MBChB is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

Alan BR Thomson, MD Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Alberta, Canada

Alan BR Thomson, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alberta Medical Association, American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, Canadian Association of Gastroenterology, Canadian Medical Association, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Noel Williams, MD Professor Emeritus, Department of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Noel Williams, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Jay A Yelon, DO, FACS Associate Professor of Surgery and Anesthesiology, Program Director, Surgical Critical Care Fellowship, New York Medical College; Chief, Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, Westchester Medical Center

Jay A Yelon, DO, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, American Burn Association, American College of Surgeons, American Trauma Society, Association for Academic Surgery, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, Pan American Trauma Society, Shock Society, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Southeastern Surgical Congress, and Surgical Infection Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.