Dialysis Complications of Chronic Renal Failure: Practice Essentials, Electrolyte Abnormalities, Neurologic Complications (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

In persons with kidney disease, the kidneys are damaged and cannot filter blood properly, causing waste to build up in the body. Kidney disease increases the risk for stroke or cardiac arrest. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is complete, permanent kidney failure that can be treated only by a kidney transplant or dialysis. Major risk factors for kidney disease include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and a family history of kidney failure. Over 661,000 people in the United States have kidney failure, of whom 468,000 are on dialysis and 193,000 have a functioning kidney transplant. [1, 2, 3]

Various complications are associated with vascular access in patients who are on hemodialysis and are associated with abdominal catheters in patients using continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). These vascular access complications are similar to those seen in any patient with a vascular surgical procedure (eg, bleeding, local or disseminated intravascular infections [DIC], vessel [graft] occlusion). The native peripheral vascular system is also affected with higher rates of amputation and revascularization procedures, and a peritoneal dialysis catheter exposes patients to the risks of peritonitis and local infection, because the catheter acts as a foreign body and provides a portal of entry for pathogens from the external environment. [4, 5]

Electrolyte abnormalities may result from renal disease itself or as an iatrogenic complication. They include hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, and hypermagnesemia. Neurologic complications include headache, dialysis dementia, dialysis disequilibrium syndrome, Wernicke’s encephalopathy, and stroke, which can occur either directly or indirectly in relation to hemodialysis. [6, 7, 4]

Patients with an arteriovenous fistula or graft should have the site examined regularly. Vascular access problems include infections, which usually manifest themselves as local pain, redness, warmth, or fluctuance. Fever may be present. Clotting of the vascular access presents as loss of normal bruit or palpable thrill. There may be signs or symptoms of distal limb ischemia. Patients may present after dialysis or minor trauma with bleeding from their vascular access site. Active bleeding can also occur from the incisional wound of a newly placed fistula or graft.

Hypotension in dialysis patients may be due to any of the causes encountered in any other patient. Consider serious causes such as bleeding, cardiac dysfunction, and sepsis. Aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms may form and progressively enlarge to compromise the skin overlying the site of venous access. Chest pain in ESRD patients occurs frequently during dialysis. A cardiac origin should be considered because of the high prevalence of coronary disease in ESRD patients.

For more information, see Chronic Renal Failure.

Electrolyte Abnormalities

Electrolyte abnormalities may result from renal disease itself or as an iatrogenic complication. In a study of potassium disorders in patients with chronic kidney disease, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), diabetes, and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers were associated with higher ods of having hyperkalemia. Heart failure and African American race were factors associated with higher odds of hypokalemia. Serum potassium levels less than 4.0 and greater than 5.0 mmol/L were significantly associated with increased mortality risk, but there was no increased risk for progression to ESRD. [8]

Hyperkalemia

Hyperkalemia is the most common clinically significant electrolyte abnormality in chronic renal failure. This condition is uncommon when patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are compliant with treatment and diet, unless an intercurrent illness such as acidosis or sepsis develops. A history of hyperkalemia requiring treatment or poor compliance with treatment should lower the threshold for ordering a potassium level.

Serum potassium levels usually should be measured in patients with chronic renal failure or ESRD who present with a systemic illness or major injury. Serum potassium rises when the serum is acidemic, even though total body potassium is unchanged. Hyperkalemia is usually asymptomatic and should be treated empirically when suspected and when arrhythmia or cardiovascular compromise is present.

Electrocardiography (ECG) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected hyperkalemia. Severely peaked T waves are a relatively specific finding, although this is not a very sensitive test for hyperkalemia in the setting of chronic renal failure. Widening of the QRS complex indicates severe hyperkalemia and must be treated aggressively and rapidly. Similar "hyperacute" T-waves may be seen early in acute MI.

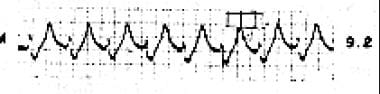

The ECG below shows large T waves and wide QRS complex.

The tracing shows a wide QRS and very large T waves. In the setting of a minimally symptomatic patient with renal failure, this must be treated as hyperkalemia until the potassium level is not elevated. Hyperkalemia may be completely asymptomatic until a lethal arrhythmia occurs. Calcium salts are the most rapid acting of the agents used to treat hyperkalemia.

Hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and hypermagnesemia

Iatrogenic complications related to fluid administration (fluid overload) or medications are frequently encountered in patients in renal failure. Dilutional hyponatremia may cause mental status changes or seizures. Hypocalcemia or hypermagnesemia may cause weakness and life-threatening dysrhythmias. Neuromuscular irritability is seen with hypocalcemia and may present as tetany or paresthesia. Hypermagnesemia causes neuromuscular depression with weakness and loss of reflexes. Acidosis may present as shortness of breath due to the work of breathing from compensatory hyperpnea.

Neurologic Complications

Headache, dialysis dementia, dialysis disequilibrium syndrome, Wernicke’s encephalopathy and stroke can occur either directly or indirectly in relation to hemodialysis (HD). [6, 7, 4]

Headache

Headache is the most commonly reported neurologic complication of dialysis patients, with a reported frequency of 27.6 to 70%. Three types of headache have been reported [6] :

- Headache with onset during dialysis without headache antecedents and fulfilling the criteria for headache related to hemodialysis on the basis ofthe International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd edition (ICHD‐II) classification.

- Headache that worsens during dialysis sessions with antecedents of primary headaches.

- Headache with onset during dialysis without headache antecedents but with headache occurring between the sessions more than 50% of the time and therefore not fulfilling the criteria for headache related to hemodialysis based on ICHD‐II classification.

According to the International Headache Society criteria, headache attributed to dialysis occurs during hemodialysis, disappearing within 72 hours after dialysis, and emerging in at least half of the hemodialysis sessions to make up a total of at least 3 attacks. Headache related to hemodialysis seems to be related to serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels and blood pressure differences between the pre‐ and post‐dialysis periods. It is possible that headache related to hemodialysis can be prevented by screening for high blood pressure and serum BUN levels before dialysis. [6]

Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome

Dialysis disequilibrium syndrome (DDS) is a neurologic complication seen in dialysis patients that is characterized by weakness, dizziness, headache, and, in severe cases, mental-status changes. The diagnosis is one of exclusion; a prime characteristic of this syndrome is that it is nonfocal. DDS usually occurs during or immediately after patients receive their first hemodialysis treatment. It is more common in children than adults and occurs more often with hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis. Risk factors for DDS include young age, severe uremia, marked reduction of urea on initial dialysis, dialysis with ultrafiltration, low dialysate sodium concentration, high-flux and large-surface-area dialyzers, and preexisting neurologic disorders. [9, 10, 11]

Strategies to prevent DDS in patients with a very high serum BUN undergoing their first hemodialysis session include the following [2] :

- Limiting the first session to 2-2.5 hours.

- Limiting the blood flow to 200-250 ml/min.

- Sodium modeling or a high sodium dialysate.

- Intravenous mannitol (1g/kg).

- Consider continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT).

Wernicke encephalopathy

Patients on dialysis are at increased risk for Wernicke encephalopathy due to decreased oral intake and loss of thiamine, as it is water soluble. It is classically described as a triad of confusion, ataxia, and ophthalmoplegia, but may involve atypical features such as neuropathy, myoclonus, and chorea. Specialist renal dietitians can provide advice to improve nutritional intake to prevent the condition. Consideration of the diagnosis and rapid recognition, with initiation of thiamine replacement if it develops, is critical to minimize any long-term neurologic deficits. [7]

Stroke

The incidence of stroke in patients undergoing dialysis is 5–10 times greater than that observed in the general population. Mortality in hemodialysis patients with stroke can be approximately 3 times higher than that in patients with chronic kidney disease not undergoing hemodialysis. Risk factors attributed to hemodialysis include thromboembolism, vascular calcification, hemodynamic instability, and amyloidosis. [4, 12]

Infection

Patients with an arteriovenous fistula or graft should have the site examined regularly. Vascular access problems include infections, which are usually manifest with typical signs and symptoms such as local pain, redness, warmth, or fluctuance. Fever may be present without local signs. Clotting of the vascular access presents as loss of normal bruit or palpable thrill. There may be signs or symptoms of distal limb ischemia.

Catheter-related bloodstream infections

Taurolidine/heparin

Taurolidine/heparin (Defencath) is indicated to reduce the incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI) in adults with kidney failure receiving chronic hemodialysis through a central venous catheter (CVC). [13]

The phase 3 LOCK-IT trial (N = 795) in patients undergoing hemodialysis showed taurolidine/heparin reduced CRBSI by 71% compared with heparin alone. [14] Event rates per 1000 catheter days were 0.13 and 0.46, respectively, with the difference in time to CRBSI being statistically significant, favoring taurolidine/heparin (P< 0.001).

CAPD-associated peritonitis

Peritonitis is common in patients who are being treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), occurring approximately once per patient year. Patients present with generalized abdominal pain, which may be mild, or complain of a cloudy effluent. Localized pain and tenderness suggest a local process, such as incarcerated hernia or appendicitis. Severe generalized peritonitis may be due to a perforated viscus, as in any other patient. Fever is often absent. [2, 5, 15, 16, 17]

The diagnosis of CAPD-associated peritonitis is confirmed by culture of effluent dialysate (ie, peritoneal fluid), which should be ordered before empiric treatment. Presumptive diagnosis is based on a peritoneal fluid white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 100/mL or a positive Gram stain. The effluent is often cloudy when peritonitis is present, and this appearance accurately predicts elevated WBC counts. In patients without peritonitis, WBC counts of 0-50/mL with a mononuclear predominance are considered normal. Cell counts are usually much higher with predominant polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) when peritonitis is present. However, some culture-positive specimens have less than 100 WBCs.

Peritoneal dialysis is the most frequent dialysis method in children, and peritonitis is a frequent complication. Congenital abnormality of the kidney and urinary tract was found to be a significant risk factor for nosocomial peritonitis in pediatric patients with ESRD undergoing peritoneal dialysis. [15]

A number of prophylactic strategies have been employed to reduce the occurrence of peritonitis, including the use of oral, nasal, and topical antibiotics; disinfection of the exit site; modification of the transfer set used in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis exchanges; changes to the design of the peritoneal dialysis catheter implanted; the surgical method by which the peritoneal dialysis catheter is inserted; the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing certain invasive procedures; and the administration of antifungal prophylaxis to peritoneal dialysis patients whenever they are given an antibiotic treatment course. [5]

Hemorrhage

Patients may present after dialysis or minor trauma with bleeding from their vascular access site. Active bleeding can also occur from the incisional wound of a newly placed fistula or graft. The bleeding can usually be controlled with elevation and firm but nonocclusive pressure. In the immediate postdialysis period, protamine may be needed to reverse the effect of heparin (routinely used in dialysis to prevent clotting). Note that life-threatening bleeding may occur. [2, 12]

Anemia is inevitable in chronic renal failure because of loss of erythropoietin production. Abnormalities in white cell and platelet functions lead to increased susceptibility to infection and easy bleeding and bruising. This condition results in fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, decreased cognition, and impaired immunity. [18, 19]

Aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms may form and progressively enlarge to compromise the skin overlying the site of venous access. These present as localized swelling, which may be pulsatile, and are often chronic. A rapid increase in size may indicate active bleeding.

Treatment and Management Considerations

Peripheral hemodialysis access sites may be used to draw blood or infuse medications and fluids in an emergency when no other access is available. A central venous access device may be used with the usual precautions. In an immediately life-threatening emergency, the following procedure may be used. The site should not be used for routine intravenous access. [2, 5, 10, 11, 16, 17]

- Do not use a tourniquet.

- Avoid puncturing the back wall of the vessel.

- Carefully secure all intravenous (IV) catheters; infusions may need to be under pressure because of relatively high pressures at the access site.

- Apply firm but nonocclusive pressure for 10-15 minutes after accessing a peripheral hemodialysis access site.

- Document presence of a thrill before and after procedure.

Consider consultation with a nephrologist and/or vascular surgeon for the following problems:

- Need for urgent dialysis.

- Significant deterioration from baseline renal function.

- CAPD-associated peritonitis or catheter-associated infection.

- Infection, obstruction, or expanding aneurysm/pseudoaneurysm of the vascular access.

Other problems that may arise in the dialysis patient include the following:

- Changes in calcium and phosphorus metabolism, acidosis

- Lipid disorders

- Pericarditis

- Serositis

- Gout, pseudogout

- Hypothyroidism, seizures, fractures

- Accelerated hypertension

- Infertility, impotence, spontaneous abortion

- Bleeding, gastrointestinal mucosal ulcerations, arteriovenous malformations

Hypotension and shock

Hypotension in dialysis patients may be due to any of the causes encountered in any other patient. Consider serious causes such as bleeding, cardiac dysfunction, and sepsis.

IV fluids should not be administered routinely (as is done for many ED patients). When used, the preferred regimen is small bolus doses of normal saline (approximately 200-250 mL), with reevaluation for effect between doses. Lactated Ringer solution should not be used because of the potassium content.

Cardiac dysfunction

Chest pain in ESRD patients occurs frequently during dialysis. A cardiac origin should usually be considered due to the high prevalence of coronary disease in ESRD patients.

Cardiac arrest in a patient with chronic renal failure or ESRD may be due to hyperkalemia. Consider treatment with IV calcium and IV bicarbonate while awaiting laboratory confirmation. Nebulized albuterol may also be used for temporary lowering of serum potassium levels, when appropriate.

Consider pericardial tamponade, especially in the setting of pulseless electrical activity (PEA). If tamponade is suspected, consider pericardiocentesis. If bedside ultrasound is available, this can confirm the diagnosis and guide pericardiocentesis.

Nitrates (oral, topical, or IV) can be temporarily effective for patients with fluid overload.

Hemorrhage

Bleeding may be due to uremic coagulopathy or from anticoagulation during hemodialysis. In the latter case, the heparin effect may be reversed with protamine. Desmopressin (DDAVP) by nasal, subcutaneous, or IV routes and cryoprecipitate are effective in correction of uremic coagulopathy. Applying firm but nonocclusive pressure for 10-15 minutes best treats bleeding from a vascular access site.

Infection and peritonitis

CAPD-associated peritonitis is often treated with a loading dose of parenteral antibiotic, followed by a period of intraperitoneal antibiotics. A systematic review found that IV antibiotics are not needed. [16] Institutions that treat CAPD patients may have a standard protocol for treatment. In most cases, the patient's nephrologist should be consulted, especially if there is no institutional consensus on optimal treatment. When there is evidence of local infection around the CAPD catheter, systemic antibiotics should be used.

Outcome of Patients on Dialysis

The mortality rate of dialysis patients is approximately 20% despite careful attention to fluid and electrolyte balance or other treatment. More than 30% of patients who begin dialysis die within the first year of the initiation of treatment. The most common cause of sudden death in patients with ESRD is hyperkalemia, which is often encountered in patients after missed dialysis or dietary indiscretion. In addition, the cardiovascular mortality is 10-20 times higher in dialysis patients than in the normal population. All-cause mortality in dialysis patients older than 65 years is more than 6 times the general population. [3]

The morbidity and mortality of dialysis patients is much higher in the United States than in most other countries, which is probably a consequence of selection bias. US patients receiving dialysis are on the average older and sicker than those in other countries. [20]

Since 1996, the mortality rate associated with dialysis has decreased by 28%, and that associated with kidney transplantation has declined by 40%. Cardiovascular disease is the cause of over 50% of deaths in patients with ESRD, with arrhythmias and cardiac arrest being responsible for 37% of cardiovascular-related deaths. [1]

For more information, see Chronic Renal Failure.

Author

Chief Editor

Erik D Schraga, MD Staff Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Mills-Peninsula Emergency Medical Associates

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

David S Howes, MD Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics, Residency Program Director Emeritus, Section of Emergency Medicine, University of Chicago, University of Chicago, The Pritzker School of Medicine

David S Howes, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment

Richard H Sinert, DO Professor of Emergency Medicine, Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Research Director, State University of New York College of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Department of Emergency Medicine, Kings County Hospital Center

Richard H Sinert, DO is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.