Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL): Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

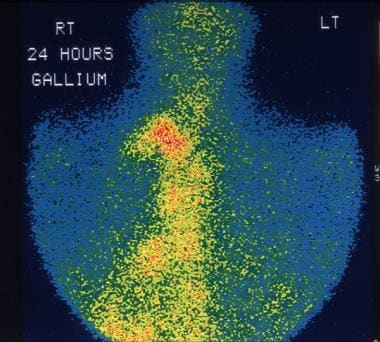

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) are tumors originating from lymphoid tissues, mainly of lymph nodes. These tumors may result from chromosomal translocations, infections, environmental factors, immunodeficiency states, and chronic inflammation. See the image below.

This 28-year-old man was being evaluated for fever of unknown origin. Gallium-67 study shows extensive uptake in the mediastinal lymph nodes due to non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Signs and symptoms

The clinical manifestations of NHL vary with such factors as the location of the lymphomatous process, the rate of tumor growth, and the function of the organ being compromised or displaced by the malignant process.

Signs and symptoms of low-grade lymphomas include the following:

- Peripheral adenopathy: Painless and slowly progressive; can spontaneously regress

- Primary extranodal involvement and B symptoms: Uncommon at presentation; however, common with advanced, malignant transformation or end-stage disease

- Bone marrow: Frequent involvement; may be associated with cytopenias(s); fatigue/weakness more common in advanced-stage disease

Intermediate- and high-grade lymphomas have a more varied clinical presentation, including the following:

- Adenopathy: Most patients

- Extranodal involvement: More than one third of patients; most common sites are GI/GU tracts (including Waldeyer ring), skin, bone marrow, sinuses, thyroid, CNS

- B symptoms: Temperature >38°C, night sweats, weight loss >10% from baseline within 6 months; in approximately 30-40% of patients

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Examination in patients with low-grade lymphomas may demonstrate peripheral adenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly.

Intermediate- and high-grade lymphomas may result in the following examination findings:

- Rapidly growing and bulky lymphadenopathy

- Splenomegaly

- Hepatomegaly

- Large abdominal mass: Usually in Burkitt lymphoma

- Testicular mass

- Skin lesions: Associated with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, and angioimmunoblastic lymphoma

Testing

Laboratory studies in a patient with suspected NHL should include the following:

- CBC count: May be normal in early-stage disease; in more advanced stages, may demonstrate anemia, thrombocytopenia/leukopenia/pancytopenia, lymphocytosis, thrombocytosis

- Serum chemistry studies: May show elevated LDH and calcium levels, abnormal liver function tests

- Serum beta2-microglobulin level: May be elevated

- HIV serology: Especially in patients with diffuse large cell immunoblastic or small noncleaved histologies

- Human T-cell lymphotropic virus–1 serology: For patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

- Hepatitis B testing: In patients in whom rituximab therapy is planned, because reactivation has been reported

Other tests that may be helpful in evaluating suspected NHL include the following:

- Immunophenotypic analysis of lymph node, bone marrow, peripheral blood

- Cytogenetic studies: NHL occasionally associated with monoclonal gammopathy; possible positive Coombs test; maybe hypogammaglobulinemia

Imaging tests

The following imaging studies should be obtained in a patient suspected of having NHL:

- Chest radiography

- Upper GI series with small bowel follow-through: In patients with head and neck involvement and those with a GI primary lesion

- CT scanning of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis

- PET scanning

- Bone scanning: Only in patients with bone pain, elevated alkaline phosphatase, or both

- Testicular ultrasonography: For opposite testis in male patients with a testicular primary lesion

- Multiple gated acquisition (MUGA) scanning: To assess cardiac function, in patients being considered for treatment with anthracyclines

- MRI of brain/spinal cord: For suspected primary CNS lymphoma, lymphomatous meningitis, paraspinal lymphoma, or vertebral body involvement by lymphoma

Procedures

The diagnosis of NHL relies on pathologic confirmation following appropriate tissue biopsy. The following are procedures in cases of suspected NHL:

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy: For staging rather than diagnostic purposes

- Excisional lymph node biopsy (extranodal biopsy): For lymphoma protocol studies

Perform lumbar puncture for CSF analysis in patients with the following conditions:

- Diffuse aggressive NHL with bone marrow, epidural, testicular, paranasal sinus, or nasopharyngeal involvement, or 2 or more extranodal sites of disease

- High-grade lymphoblastic lymphoma

- High-grade small noncleaved cell lymphomas

- HIV-related lymphoma

- Primary CNS lymphoma

- Neurologic signs and symptoms

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The treatment of NHL varies greatly, depending on various factors. Common therapies include the following:

- Chemotherapy: Most common; usually combination regimens

- Biologic agents (eg, rituximab, obinutuzumab, lenalidomide): Typically in combination with chemotherapy

- Radiation therapy

- Bone marrow transplantation: Possible role in relapsed high-risk disease

- Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy: In relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma

- Radioimmunotherapy

- Transfusions of blood products

- Antibiotics

Pharmacotherapy

Medications used in the management of NHL include the following:

- Cytotoxic agents (eg, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, fludarabine, pralatrexate, nelarabine, etoposide, mitoxantrone, cytarabine, bendamustine, carboplatin, cisplatin, gemcitabine, denileukin diftitox, bleomycin)

- Histone deacetylase inhibitors (eg, vorinostat, romidepsin, belinostat)

- Colony-stimulating factor growth factors (eg, epoetin alfa, darbepoetin alfa, filgrastim, pegfilgrastim)

- Monoclonal antibodies (eg, rituximab, ibritumomab tiuxetan, alemtuzumab, ofatumumab, obinutuzumab, pembrolizumab)

- mTOR (mechanistic [mammalian] target of rapamycin) kinase inhibitors (eg, temsirolimus)

- Proteasome inhibitors (eg, bortezomib)

- Immunomodulators (eg, interferon alfa-2a or alfa-2b)

- Corticosteroids (eg, dexamethasone, prednisone)

Surgery

Surgical intervention in NHL is limited but can be useful in selected situations (eg, GI lymphoma), particularly in localized disease or in the presence of risk of perforation, obstruction, and massive bleeding. Orchiectomy is part of the initial management of testicular lymphoma.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The term lymphoma describes a heterogeneous group of malignancies with different biology and prognosis. In general, lymphomas are divided into 2 large groups of neoplasms: non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and Hodgkin lymphoma. About 85% of all malignant lymphomas are NHLs. The median age at diagnosis is 68 years, [1] although Burkitt lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma occur in younger patients.

NHL includes many clinicopathologic subtypes, each with distinct epidemiologies; etiologies; morphologic, immunophenotypic, genetic, and clinical features; and responses to therapy. With respect to prognosis, NHLs can be divided into two groups, indolent and aggressive. [2]

Currently, several NHL classification schemas exist, reflecting the growing understanding of the complex diversity of the NHL subtypes. The Working Formulation, originally proposed in 1982, classified and grouped lymphomas by morphology and clinical behavior (ie, low, intermediate, or high grade). In the 1990s, the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) classification attempted to apply immunophenotypic and genetic features in identifying distinct clinicopathologic NHL entities. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification further elaborates upon the REAL approach. This classification divides NHL into those of B-cell origin and those of T-cell and natural killer (NK)–cell origin.

A study by Shustik et al found that within the WHO classification, the subdivisions of grade 3A and 3B had no difference in outcome or curability with anthracycline-based therapy. [3]

For clinical oncologists, the most practical way of sorting the currently recognized types of NHL is according to their predicted clinical behavior. Each classification schema contributes to a greater understanding of the disease, which dictates prognosis and treatment.

Although a variety of laboratory and imaging studies are used in the evaluation and staging of suspected NHL (see Workup), a well-processed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained section of an excised lymph node is the mainstay of pathologic diagnosis. The treatment of NHL varies greatly, depending on tumor stage, grade, and type and various patient factors (eg, symptoms, age, performance status; see Treatment and Guidelines).

For discussion of individual subtypes of NHL, see the following:

Pathophysiology

NHLs are tumors originating from lymphoid tissues, mainly of lymph nodes. Various neoplastic tumor cell lines correspond to each of the cellular components of antigen-stimulated lymphoid follicles.

NHL represents a progressive clonal expansion of B cells or T cells and/or NK cells arising from an accumulation of lesions affecting proto-oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, resulting in cell immortalization. These oncogenes can be activated by chromosomal translocations (ie, the genetic hallmark of lymphoid malignancies), or tumor suppressor loci can be inactivated by chromosomal deletion or mutation. In addition, the genome of certain lymphoma subtypes can be altered with the introduction of exogenous genes by various oncogenic viruses. Several cytogenetic lesions are associated with specific NHLs, reflecting the presence of specific markers of diagnostic significance in subclassifying various NHL subtypes.

Almost 85% of NHLs are of B-cell origin; only 15% are derived from T/NK cells, and the small remainder stem from macrophages. These tumors are characterized by the level of differentiation, the size of the cell of origin, the origin cell's rate of proliferation, and the histologic pattern of growth.

For many of the B-cell NHL subtypes, the pattern of growth and cell size may be important determinants of tumor aggressiveness. Tumors that grow in a nodular pattern, which vaguely recapitulate normal B-cell lymphoid follicular structures, are generally less aggressive than lymphomas that proliferate in a diffuse pattern. Lymphomas of small lymphocytes generally have a more indolent course than those of large lymphocytes, which may have intermediate-grade or high-grade aggressiveness. However, some subtypes of high-grade lymphomas are characterized by small cell morphology.

Etiology

NHLs may result from chromosomal translocations, infections, environmental factors, immunodeficiency states, and chronic inflammation.

Chromosomal translocations

Chromosomal translocations and molecular rearrangements play an important role in the pathogenesis of many lymphomas and correlate with histology and immunophenotype.

The t(14;18)(q32;q21) translocation is the most common chromosomal abnormality associated with NHL. This translocation occurs in 85% of follicular lymphomas and 28% of higher-grade NHLs. This translocation results in the juxtaposition of the bcl -2 apoptotic inhibitor oncogene at chromosome band 18q21 to the heavy chain region of the immunoglobulin (Ig) locus within chromosome band 14q32.

The t(11;14)(q13;q32 translocation has a diagnostic nonrandom association with mantle cell lymphoma. This translocation results in the overexpression of bcl -1 (cyclin D1/PRAD 1), a cell-cycle regulator on chromosome band 11q13.

The 8q24 translocations lead to c-myc dysregulation. This is frequently observed in high-grade small noncleaved lymphomas (Burkitt and non-Burkitt types), including those associated with HIV infection.

The t(2;5)(p23;q35) translocation occurs between the nucleophosmin (NPM) gene and the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK1) gene. It results in the expression of an aberrant fusion protein found in a majority of anaplastic large cell lymphomas.

Two chromosomal translocations, t(11;18)(q21;q21) and t(1;14)(p22;132), are associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. The more common (ie, t[11;18][q21;q21]) translocates the apoptosis inhibitor AP12 gene with the MALT1 gene, resulting in the expression of an aberrant fusion protein. The other translocation, t(1;14)(p22;132), involves the translocation of the bcl -10 gene to the immunoglobulin gene enhancer region.

Infection

Some viruses are implicated in the pathogenesis of NHL, probably because of their ability to induce chronic antigenic stimulation and cytokine dysregulation, which leads to uncontrolled B- or T-cell stimulation, proliferation, and lymphomagenesis. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a DNA virus that is associated with Burkitt lymphoma (especially the endemic form in Africa), Hodgkin disease, lymphomas in immunocompromised patients (eg, from HIV infection, [4] organ transplantation), and sinonasal lymphoma.

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) causes a latent infection via reverse transcription in activated T-helper cells. This virus is endemic in certain areas of Japan and the Caribbean islands, and approximately 5% of carriers develop adult T-cell leukemia or lymphoma.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is associated with the development of clonal B-cell expansions and certain subtypes of NHL (ie, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia), especially in the setting of essential (type II) mixed cryoglobulinemia.

Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is associated with body cavity–based lymphomas in patients with HIV infection and in patients with multicentric Castleman disease.

Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with the development of primary gastrointestinal (GI) lymphomas, particularly gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors linked to the development of NHL include chemicals (eg, pesticides, herbicides, solvents, organic chemicals, wood preservatives, dusts, hair dye), chemotherapy, and radiation exposure. A study by Antonopoulos et al found that maternal smoking during pregnancy may have a modest increase in the risk for childhood NHL but not HL. [5]

Immunodeficiency states

Congenital immunodeficiency states (eg, severe combined immunodeficiency disease [SCID], Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome), acquired immunodeficiency states (eg, AIDS), and induced immunodeficiency states (eg, immunosuppression) are associated with increased incidence of NHL and are characterized by a relatively high incidence of extranodal involvement, particularly of the GI tract, and with aggressive histology. Primary CNS lymphomas can be observed in about 6% of patients with AIDS.

Celiac disease has been associated with an increased risk of malignant lymphomas. The risk of lymphoproliferative malignancy in individuals with celiac disease depends on small intestinal histopathology; no increased risk is observed in those with latent celiac disease. [6]

Chronic inflammation

The chronic inflammation observed in patients with autoimmune disorders, such as Sjögren syndrome and Hashimoto thyroiditis, promotes the development of MALT and predisposes patients to subsequent lymphoid malignancies. Hashimoto thyroiditis is a preexisting condition in 23-56% of patients with primary thyroid lymphomas.

Epidemiology

The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 80,620 new cases of NHL will be diagnosed in 2024. [7] From the early 1970s to the early 21st century, the incidence rates of NHL nearly doubled. Although some of this increase may be attributable to earlier detection (resulting from improved diagnostic techniques and access to medical care), or possibly to HIV-associated lymphomas, for the most part the rise is unexplained. Since 2015, incidence rates of NHL have declined by about 1% per year. [7]

NHL is the most prevalent hematopoietic neoplasm, representing approximately 4.0% of all cancer diagnoses and ranking eighth in frequency among all cancers. NHL is more than 5 times as common as Hodgkin lymphoma. [1]

Overall, NHL is most often diagnosed in people aged 65-74; median age at diagnosis is 68 years. [1] The exceptions are high-grade lymphoblastic and small noncleaved lymphomas, which are the most common types of NHL observed in children and young adults. At diagnosis, low-grade lymphomas account for 37% of NHLs in patients aged 35-64 years but account for only 16% of cases in patients younger than 35 years. Low-grade lymphomas are extremely rare in children.

Prognosis

The 5-year relative survival rate of patients with NHL is 74.3%. [1] The survival rate has steadily improved over the last 2 decades, thanks to improvements in medical and nursing care, the advent of novel therapeutic strategies (eg, monoclonal antibodies, chimeric antigen receptor [CAR] T-cell therapy), validation of biomarkers of response, and the implementation of tailored treatment.

The prognosis for patients with NHL depends on the following factors:

- Tumor histology (based on Working Formulation classification)

- Tumor stage

- Patient age

- Tumor bulk

- Performance status

- Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level

- Beta2-microglobulin level

- Presence or absence of extranodal disease

In general, these clinical characteristics are thought to reflect the following host or tumor characteristics:

- Tumor growth and invasive potential (eg, LDH, stage, tumor size, beta2-microglobulin level, number of nodal and extranodal sites, bone marrow involvement)

- Patient's response to tumor (eg, performance status, B symptoms)

- Patient's tolerance of intensive therapy (eg, performance status, patient age, bone marrow involvement)

The International Prognostic Index (IPI), which was originally designed as a prognostic factor model for aggressive NHL, also appears to be useful for predicting the outcome of patients with low-grade lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. This index is also used to identify patients at high risk of relapse, based on specific sites of involvement, including bone marrow, CNS, liver, testis, lung, and spleen. These patients may be considered for clinical trials that aim at improving the current treatment standard.

An age-adjusted model for patients younger than 60 years has been proposed. In younger patients, stage III or IV disease, high LDH levels, and nonambulatory performance status are independently associated with decreased survival rates.

Pediatric and adolescent patients have better outcome than adults with CNS lymphoma. [8] An ECOG performance status score of 0-1 is associated with improved survival. Higher dose methotrexate is associated with slightly better response.

Clinical features included in the IPI that are independently predictive of survival include the following:

- Age - Younger than 60 years versus older than 60 years

- LDH level - Within the reference range versus elevated

- Number of extranodal sites - Zero to 1 versus more than 1

With this model, relapse-free and overall survival rates at 5 years are as follows:

- 0-1 risk factors - 75%

- 2-3 risk factors - 50%

- 4-5 risk factors - 25%

For patients with follicular lymphoma—the second most common subtype of NHL—the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score appears to be more discriminating than the IPI. [9] The FLIPI score is calculated on the basis of 5 adverse prognostic factors, as follows:

- Age (> 60 y)

- Ann Arbor stage (III-IV)

- Hemoglobin level (< 12 g/dL)

- Number of nodal areas (> 4)

- Serum LDH level (above normal)

Three risk groups are defined by FLIPI score:

- Low risk (0-1 adverse factor)

- Intermediate risk (2 factors)

- Poor risk (3 or more adverse factors)

Biomarkers in tumor cells such as the expression of bcl- 2 or bcl- 6 proteins and cDNA microarray provide useful prognostic information.

Patients with congenital or acquired immunodeficiency have an increased risk of lymphoma and respond poorly to therapy.

Time to achieve complete remission (CR) and response duration has prognostic significance. Patients who do not achieve CR by the third cycle of chemotherapy have a worse prognosis than those who achieve rapid CR.

Immunophenotype is also a factor. Patients with aggressive T- or NK-cell lymphomas generally have worse prognoses than those with B-cell lymphomas, except the Ki-1 anaplastic large T- or null-cell lymphomas.

Cytogenetic abnormalities and oncogene expression affect prognosis. Patients with lymphomas with 1, 7, and 17 chromosomal abnormalities have worse prognoses than those with lymphomas without these changes.

Low-grade lymphomas have indolent clinical behavior and are associated with a comparatively prolonged survival (median survival is 6-10 y), but they have little potential for cure when the disease manifests in more advanced stages. They also have the tendency to transform to high-grade lymphomas.

Approximately 70% of all patients with intermediate- and high-grade NHL relapse or never respond to initial therapy. Most recurrences are within the first 2 years after therapy completion. Patients with relapsed or resistant NHL have a very poor prognosis (< 5-10% are alive at 2 years with conventional salvage chemotherapy regimens).

Drake et al found that low levels of vitamin D were associated with a decrease in clinical end points (event-free survival and overall survival) in subsets of patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma (ie, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or T-cell lymphoma). [10] Although the results of this study suggest an association between vitamin D levels and its metabolism with the biology of some aggressive lymphomas, further studies are needed before conclusions can be drawn.

A study by Change et al also found a protective effect associated with vitamin D and also concluded that routine residential UV radiation exposure may have a protective effect against lymphomagenesis through mechanisms possibly independent of vitamin D. [11]

Survivors of NHL are at risk for development of a second primary malignancy. A review of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data from 1992-2008 found hazard ratios for a second cancer to be 2.70 for men and 2.88 for women. [12]

Patient Education

Patients should receive a clear and detailed explanation of all the available treatment options, prognosis, and adverse effects of treatment. Advise patients to call their oncologists as necessary and educate patients about oncologic emergencies that require an immediate emergency department visit. Suggest psychosocial counseling.

For patient education information, see Lymphoma.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. National Cancer Institute. Available at https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/nhl.html. Accessed: May 28, 2024.

- PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. May 18, 2023. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Shustik J, Quinn M, Connors JM, et al. Follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma grades 3A and 3B have a similar outcome and appear incurable with anthracycline-based therapy. Ann Oncol. 2011 May. 22(5):1164-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Martí-Carvajal AJ, Cardona AF, Lawrence A. Interventions for previously untreated patients with AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jul 8. CD005419. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Antonopoulos CN, Sergentanis TN, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011 Dec 1. 129(11):2694-703. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Elfstrom P, Granath F, Ekstrom Smedby K, et al. Risk of lymphoproliferative malignancy in relation to small intestinal histopathology among patients with celiac disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 Mar 2. 103(5):436-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Available at https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/2024-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf. Accessed: May 28, 2024.

- Abla O, Weitzman S, Blay JY, O'Neill BP, Abrey LE, Neuwelt E, et al. Primary CNS lymphoma in children and adolescents: a descriptive analysis from the international primary CNS lymphoma collaborative group (IPCG). Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Jan 15. 17(2):346-52. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004 Sep 1. 104 (5):1258-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Drake MT, Maurer MJ, Link BK, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency and prognosis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Sep 20. 28(27):4191-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang ET, Canchola AJ, Cockburn M, et al. Adulthood residential ultraviolet radiation, sun sensitivity, dietary vitamin D, and risk of lymphoid malignancies in the California Teachers Study. Blood. 2011 Aug 11. 118(6):1591-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Donin N, Filson C, Drakaki A, Tan HJ, Castillo A, Kwan L, et al. Risk of second primary malignancies among cancer survivors in the United States, 1992 through 2008. Cancer. 2016 Jul 5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhang QY, Foucar K. Bone marrow involvement by Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009 Aug. 23(4):873-902. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fernberg P, Edgren G, Adami J, et al. Time trends in risk and risk determinants of non-hodgkin lymphoma in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011 Nov. 11(11):2472-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hsia CC, Howson-Jan K, Rizkalla KS. Hodgkin lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Dermatol Online J. 2009 May 15. 15(5):5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hussain SK, Zhu W, Chang SC, Breen EC, Vendrame E, Magpantay L, et al. Serum Levels of the Chemokine CXCL13, Genetic Variation in CXCL13 and Its Receptor CXCR5, and HIV-Associated Non-Hodgkin B-Cell Lymphoma Risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013 Feb. 22(2):295-307. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rossi M, Pertovaara H, Dastidar P, et al. Computed tomography-based tumor volume in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: clinical correlation and comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009 Jul-Aug. 33(4):641-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- von Falck C, Rodt T, Joerdens S, et al. F-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for the detection of radicular and peripheral neurolymphomatosis: correlation with magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Clin Nucl Med. 2009 Aug. 34(8):493-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zinzani PL, Gandolfi L, Broccoli A, et al. Midtreatment 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2011 Mar 1. 117(5):1010-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Terezakis SA, Hunt MA, Kowalski A, et al. [¹8F]FDG-positron emission tomography coregistration with computed tomography scans for radiation treatment planning of lymphoma and hematologic malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Nov 1. 81(3):615-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khan AB, Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, et al. PET-CT staging of DLBCL accurately identifies and provides new insight into the clinical significance of bone marrow involvement. Blood. 2013 May 9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mac Manus MP, Rainer Bowie CA, Hoppe RT. What is the prognosis for patients who relapse after primary radiation therapy for early-stage low-grade follicular lymphoma?. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998 Sep 1. 42(2):365-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rossier C, Schick U, Miralbell R, et al. Low-dose radiotherapy in indolent lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 Nov 1. 81(3):e1-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peyrade F, Jardin F, Thieblemont C, et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May. 12(5):460-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, Banat GA, etc. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013 Feb 19. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. B-cell Lymphomas. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf. Version 2.2024 — April 30, 2024; Accessed: May 28, 2024.

- Horvath B, Demeter J, Eros N, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: Remission after rituximab-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Jul 24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barr PM, Fu P, Lazarus HM, et al. Phase I trial of fludarabine, bortezomib and rituximab for relapsed and refractory indolent and mantle cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2009 Jun 29. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Tobinai K, Ishizawa KI, Ogura M, et al. Phase II study of oral fludarabine in combination with rituximab for relapsed indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2009 Jun 17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Watanabe T, Tobinai K, Shibata T, et al. Phase II/III Study of R-CHOP-21 Versus R-CHOP-14 for Untreated Indolent B-Cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: JCOG 0203 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Oct 20. 29(30):3990-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Czuczman MS, Koryzna A, Mohr A, et al. Rituximab in combination with fludarabine chemotherapy in low-grade or follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Feb 1. 23(4):694-704. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barta SK, Li H, Hochster HS, Hong F, Weller E, Gascoyne RD, et al. Randomized phase 3 study in low-grade lymphoma comparing maintenance anti-CD20 antibody with observation after induction therapy: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E1496). Cancer. 2016 Jun 28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sehn LH, Chua N, Mayer J, Dueck G, Trněný M, Bouabdallah K, et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016 Jun 23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993 Apr 8. 328(14):1002-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Oct 1. 23(28):7013-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rummel MJ, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab is superior in respect to progression free survival and CR rate when compared to CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment in patients with advanced follicular, indolent, and mantle cell lymphomas. [abstract: American Society of Hematology]. Blood. 2009. 114:405.

- Weidmann E, Neumann A, Fauth F, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in combination with rituximab as first-line treatment in patients 80 years or older with aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2011 Aug. 22(8):1839-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Goy A, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma: updated time-to-event analyses of the multicenter phase 2 PINNACLE study. Ann Oncol. 2009 Mar. 20(3):520-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R, Fermé C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 20. 23(18):4117-26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A, et al for the MabThera International Trial Group. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006 May. 7(5):379-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Smith SM, van Besien K, Karrison T, Dancey J, McLaughlin P, Younes A, et al. Temsirolimus has activity in non-mantle cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma subtypes: The University of Chicago phase II consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Nov 1. 28(31):4740-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Leahy MF, Seymour JF, Hicks RJ, Turner JH. Multicenter phase II clinical study of iodine-131-rituximab radioimmunotherapy in relapsed or refractory indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 20. 24(27):4418-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gopal AK, Rajendran JG, Gooley TA, Pagel JM, Fisher DR, Petersdorf SH. High-dose [131I]tositumomab (anti-CD20) radioimmunotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for adults > or = 60 years old with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Apr 10. 25(11):1396-402. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kaminski MS, Zelenetz AD, Press OW, Saleh M, Leonard J, Fehrenbacher L. Pivotal study of iodine I 131 tositumomab for chemotherapy-refractory low-grade or transformed low-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Oct 1. 19(19):3918-28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Milpied N, Deconinck E, Gaillard F, Delwail V, Foussard C, Berthou C. Initial treatment of aggressive lymphoma with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell support. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar 25. 350(13):1287-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Leonard, John P., et al. AUGMENT: A Phase III Study of Lenalidomide Plus Rituximab Versus Placebo Plus Rituximab in Relapsed or Refractory Indolent Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 10. 37 (14):1188-1199. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Gopal AK, Kahl BS, de Vos S, Wagner-Johnston ND, Schuster SJ, Jurczak WJ, et al. PI3Kd inhibition by idelalisib in patients with relapsed indolent lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2014 Mar 13. 370(11):1008-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Dreyling M, Santoro A, Mollica L, Leppä S, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Inhibition by Copanlisib in Relapsed or Refractory Indolent Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Dec 10. 35 (35):3898-3905. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Flinn IW, Miller CB, Ardeshna KM, Tetreault S, et al. DYNAMO: A Phase II Study of Duvelisib (IPI-145) in Patients With Refractory Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Apr 10. 37 (11):912-922. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ukoniq (umbralisib) [package insert]. Edison, NJ: TG Therapeutics, Inc. February 2021. Available at [Full Text].

- Sehn LH, Herrera AF, Matasar MJ, et al. Addition of polatuzumab vedotin to bendamustine and rituximab (BR) improves outcomes in transplant-ineligible patients with relapsed/refractory (r/r) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) versus BR alone: Results from a randomized phase 2 study. Blood. 2017. 130:2821. [Full Text].

- Tixier F, Ranchon F, Iltis A, Vantard N, Schwiertz V, Bachy E, et al. Comparative toxicities of 3 platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens in relapsed/refractory lymphoma patients. Hematol Oncol. 2016 Jul 5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Blay J, Gomez F, Sebban C. The International Prognostic Index correlates to survival in patients with aggressive lymphoma in relapse: analysis of the PARMA trial. Parma Group. Blood. 1998 Nov 15. 92(10):3562-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Somers R, Van der Lelie H, Bron D, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995 Dec 7. 333(23):1540-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Majhail NS, Bajorunaite R, Lazarus HM, et al. Long-term survival and late relapse in 2-year survivors of autologous haematopoietic cell transplantation for Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2009 Jul 1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Malik SM, Liu K, Qiang X, Sridhara R, Tang S, McGuinn WD Jr, et al. Folotyn (pralatrexate injection) for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: U.S. Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Oct 15. 16(20):4921-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Piekarz RL, Frye R, Prince HM, Kirschbaum MH, Zain J, Allen SL, et al. Phase 2 trial of romidepsin in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011 Jun 2. 117(22):5827-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bristol Myers Squibb Statement on Istodax® (romidepsin) Relapsed/Refractory Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma U.S. Indication. Bristol Myers Squibb. Available at https://news.bms.com/news/details/2021/Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Statement-on-Istodax-romidepsin-Relapsed-Refractory-Peripheral-T-cell-Lymphoma-U.S.-Indication/default.aspx. August 2, 2021; Accessed: August 3, 2021.

- FDA approves Beleodaq to treat rare, aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available at https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170112023831/https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm403929.htm. July 3, 2014; Accessed: February 24, 2021.

- O’Connor OA, Masszi T, Savage KJ, Pinter-Brown LC, Foss FM, Popplewell L, et al. Belinostat, a novel pan-histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi), in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (R/R PTCL): Results from the BELIEF trial (abstract 8507). Presented at the 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, IL. May 31-June 4, 2013.

- Jacobsen ED, Kim HT, Ho VT, et al. A large single-center experience with allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome. Ann Oncol. 2011 Jul. 22(7):1608-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Bilora F, Pietrogrande F, Campagnolo E, et al. Are Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin patients at a greater risk of atherosclerosis? A follow-up of 3 years. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009 Aug 26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- FDA approves CAR-T cell therapy to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Available at https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm581216.htm. October 18, 2017; Accessed: February 24, 2021.

- Neelapu SS, Jacobson CA, Ghobadi A, et al. Five-year follow-up of ZUMA-1 supports the curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2023 May 11. 141 (19):2307-2315. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer. 1982 May 15. 49 (10):2112-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994 Sep 1. 84 (5):1361-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul. 36 (7):1720-1748. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Sep 20. 32 (27):3059-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993 Sep 30. 329 (14):987-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, Luminari S, Lopez-Guillermo A, Vitolo U, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Sep 20. 27 (27):4555-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008 Jan 15. 111 (2):558-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphomas: implications for clinical practice and translational research. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009. 523-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Dreyling M, Ghielmini M, Marcus R, Salles G, Vitolo U, Ladetto M, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014 Sep. 25 Suppl 3:iii76-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Brice P, Bastion Y, Lepage E, Brousse N, Haïoun C, Moreau P, et al. Comparison in low-tumor-burden follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy, prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Mar. 15 (3):1110-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Zucca E, Copie-Bergman C, Ricardi U, Thieblemont C, Raderer M, Ladetto M, et al. Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013 Oct. 24 Suppl 6:vi144-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Rohatiner A, d'Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, et al. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994 May. 5 (5):397-400. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Dragosics B, Morgner A, Wotherspoon A, De Jong D. Paris staging system for primary gastrointestinal lymphomas. Gut. 2003 Jun. 52 (6):912-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Dreyling M, Geisler C, Hermine O, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Le Gouill S, Rule S, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014 Sep. 25 Suppl 3:iii83-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jun 20. 346 (25):1937-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Tilly H, Gomes da Silva M, Vitolo U, Jack A, Meignan M, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015 Sep. 26 Suppl 5:v116-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Olszewski AJ. Population-based prognostic factors for survival in patients with Burkitt lymphoma: an analysis from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer. 2013 Oct 15. 119 (20):3672-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Primary Cutaneous Lymphomas. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/primary_cutaneous.pdf. Version 2.2024 — May 6, 2024; Accessed: May 28, 2024.

- [Guideline] Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, Bagot M, Berti E, Cerroni L, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008 Sep 1. 112 (5):1600-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005 May 15. 105 (10):3768-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, Whittaker S, Olsen EA, Ranki A, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007 Jul 15. 110 (2):479-84. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Trautinger F, Knobler R, Willemze R, Peris K, Stadler R, Laroche L, et al. EORTC consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2006 May. 42 (8):1014-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, Specht L, Ladetto M, ESMO Guidelines Committee. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018 Oct 1. 29 (Suppl 4):iv30-iv40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, et al. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007 Sep 15. 110 (6):1713-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Olsen EA, Whittaker S, Kim YH, et al. Clinical end points and response criteria in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a consensus statement of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jun 20. 29 (18):2598-607. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011 Oct 13. 118 (15):4024-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Horwitz SM, Kim YH, Foss F, Zain JM, Myskowski PL, Lechowicz MJ, et al. Identification of an active, well-tolerated dose of pralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012 May 3. 119 (18):4115-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kim YH, Tavallaee M, Sundram U, Salva KA, Wood GS, Li S, et al. Phase II Investigator-Initiated Study of Brentuximab Vedotin in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome With Variable CD30 Expression Level: A Multi-Institution Collaborative Project. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov 10. 33 (32):3750-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Coauthor(s)

Francisco J Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, MD Professor of Medicine, Department of Medical Oncology, Associate Professor of Immunology, Department of Immunology, Chief, Lymphoma and Myeloma Section, Director, The Lymphoma Translational Research Program, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, University of Buffalo State University of New York School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

Francisco J Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for Cancer Research, American Society of Hematology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Emmanuel C Besa, MD Professor Emeritus, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, Kimmel Cancer Center, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University

Emmanuel C Besa, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for Cancer Education, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American College of Clinical Pharmacology, American Federation for Medical Research, American Society of Hematology, New York Academy of Sciences

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Koyamangalath Krishnan, MD, FRCP, FACP Paul Dishner Endowed Chair of Excellence in Medicine, Professor of Medicine and Chief of Hematology-Oncology, James H Quillen College of Medicine at East Tennessee State University

Koyamangalath Krishnan, MD, FRCP, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, American Society of Hematology, and Royal College of Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Lakshmi Rajdev, MD Site Director, Jacobi Medical Center; Assistant Professor, Department of Radiation Oncology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Joseph A Sparano, MD Professor of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Cancer Center; Program Director, Director of Breast Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Oncology, Montefiore Medical Center

Joseph A Sparano, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for Cancer Research, American College of Physicians, and American Society of Hematology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Salary Employment