Systemic Mastocytosis: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

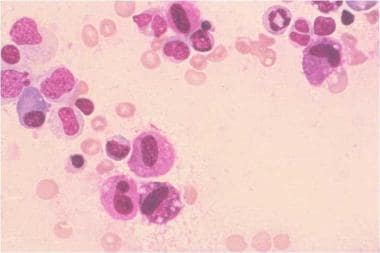

Systemic mastocytosis, often termed systemic mast cell disease (SMCD), is characterized by infiltration of clonally derived mast cells in different tissues, including bone marrow (see the image below), skin, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the liver, and the spleen. [1, 2, 3] Median survival ranges from 198 months in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis to 41 months in aggressive systemic mastocytosis and 2 months in acute mast cell leukemia.

Systemic mastocytosis. Bone marrow aspirate, Romanowsky stain, high-definition magnification. Diagnosis is mastocytosis, and morphology is abnormal mast cells. This is a bone marrow smear from a patient with systemic mastocytosis. Several mast cells are present in this photograph. These mast cells are larger than normal mast cells and have more irregularly shaped nuclear outlines and less densely packed mast cell granules. Courtesy of the American Society of Hematology Slide Bank. Used with permission.

Signs and symptoms

Manifestations of systemic mastocytosis may include the following:

- Anemia and coagulopathy

- Abdominal pain is the most common GI symptom, followed, by diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting

- Symptoms and signs of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Pruritus and flushing

- Anaphylactoid reaction (eg, to Hymenoptera stings, general anesthetics, intravenous contrast media, other drugs, foods) [4, 5]

- Neuropsychiatric manifestations (eg, depression, mood changes, lack of concentration, short memory span, increased somnolence, irritability, and emotional instability) [6]

- Increased risk of developing osteopenia and osteoporosis [7]

Findings on physical examination may include the following:

- Signs of anemia (eg, pallor)

- Hepatomegaly (27%)

- Splenomegaly (37%)

- Lymphadenopathy (21%)

- Urticaria (41%)

- Osteolysis and pathological fractures (rare)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Findings on blood studies may include the following:

- Anemia (45% of patients)

- Thrombocytopenia

- Leukocytosis

- Some patients have eosinophilia, basophilia, thrombocytosis, monocytosis and circulating mast cells

- The combination of anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, and excess bone marrow blasts (> 5%) portends a poor prognosis [8]

Measurement of serum tryptase may reveal the following:

- Total serum tryptase levels of 20 ng/mL or higher in a baseline serum sample with a total–to–beta-tryptase ratio greater than 20:1 [9]

- Serum tryptase levels of 11.5 ng/mL or higher (the cut-off value used in more recent studies) are found in more than 50% of patients

The following imaging studies may be necessary to identify the extent and stage of the disease:

- GI radiography, ultrasonography, and liver-spleen computed tomography scanning in patients with abdominal pain

- Skeletal surveys and bone CT scanning in patients with suspected bone involvement

Diagnostic procedures are as follows:

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are essential

- GI procedures (eg, barium studies, endoscopy) are indicated for patients with GI symptoms

- Liver biopsy can show mast cell infiltration in patients with hepatomegaly

- Skin biopsy may be warranted in patients with cutaneous manifestations

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) published revised criteria for diagnosing systemic mastocytosis and added a new bone marrow mastocytosis (BMM) subtype. [10] Diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis requires the presence of a major criterion plus one minor criterion, or the presence of three minor criteria. The WHO major diagnostic criterion for systemic mastocytosis is the presence of multifocal, dense infiltrates of mast cells in bone marrow or in other extracutaneous tissues. Mast cells should be seen in aggregates of 15 cells or more. [11]

The major criterion may be absent in early disease. In this situation, three of the following four minor criteria are required to make the diagnosis [10] :

- Spindle shape or atypical mast cell morphology (type I or type II) in 25% or more of the mast cells in biopsy sections of bone marrow or other extracutaneous organs

- Presence of KIT-activating KIT point mutation(s) at codon 816 or in other critical regions of KIT in bone marrow or another extracutaneous organ

- Expression of CD25 and/or CD2 and/or CD30 in addition to normal mast cell markers

- Serum/plasma total tryptase levels persistently greater than 20 ng/mL

The WHO classifies systemic mastocytosis into subtypes, depending on the presence of typical clinical findings (B and C findings). B findings, which refer to organ involvement without organ failure, are as follows [11] :

- Elevated grade of mast cell infiltration - Bone marrow biopsy showing > 30% infiltration by mast cells (focal, dense aggregates) and/or serum total tryptase level > 200 mg/mL and/or KIT D816V variant allele frequency _(_VAF) ≥10% in bone marrow or peripheral blood leukocytes

- Dysmyelopoiesis - Signs of myelodysplasia or myeloproliferation in non–mast cell lineage(s) but insufficient criteria for definitive diagnosis of an associated hematologic neoplasm**,** with the blood picture normal or only slightly abnormal

- Organomegaly on palpation or imaging - Hepatomegaly without impairment of liver function, and/or palpable splenomegaly without hypersplenism, and/or lymphadenopathy

C findings, which refer to organ involvement with organ dysfunction, are as follows [11] :

- Cytopenias – Bone marrow dysfunction manifested by one or more cytopenia (neutrophil count [ANC] < 1 × 109/L, hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, or platelets < 100 × 109/L) with no obvious non–mast cell hematopoietic malignancy

- Palpable hepatomegaly with elevated liver enzyme levels, ascites, and/or portal hypertension

- Skeletal involvement with large osteolytic lesions and/or severe osteoporosis and pathologic fractures

- Palpable splenomegaly with hypersplenism

- Malabsorption with hypoalbuminemia and weight loss due to GI mast cell infiltrates

WHO subtypes of systemic mastocytosis are as follows [10] :

- Bone marrow mastocytosis (BMM) – Diagnostic criteria include the presence of less than two B findings and the absence of C findings. Bone marrow aspirate smears show < 20% mast cells.

- Indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM) – This is the most common form of systemic mastocytosis. No C findings are present. ISM follows a stable or slowly progressing clinical course and carries a good prognosis in most patients.

- Smoldering systemic mastocytosis (SSM) – Diagnostic criteria include the presence of two or more B findings and the absence of C findings.

- Systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN) – Diagnostic criteria include the presence of aclonal hematologic non–mast cell lineage disorder (eg, myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS], myeloproliferative neoplasm [MPN], acute myeloid leukemia [AML], lymphoma)

- Aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM) – Diagnostic criteria include the presence of C findings, with no features of mast cell leukemia.

- Mast cell leukemia (MCL) – Bone marrow biopsy shows a diffuse infiltration, usually compact, by atypical, immature mast cells. Bone marrow aspirate smears show ≥20% mast cells.

SM-AHN, ASM, and MCL are collectively referred to as advanced systemic mastocytosis.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Therapy for systemic mastocytosis is primarily symptomatic; no established therapy is curative. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation has the potential ability to cure advanced systemic mastocytosis but is considered experimental.

Treatment modalities include the management of the following:

- Anaphylaxis and related symptoms

- Pruritus and flushing

- Intestinal malabsorption

Agents for symptomatic relief include the following:

- Epinephrine is used in acute anaphylaxis

- Histamine H1 antagonists (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, cetirizine, desloratadine) have been used to treat pruritus and flushing

- Histamine H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitors have been used to treat gastric hypersecretion and peptic ulcer disease

- Cromolyn is helpful for decreasing bone pain and headaches, controlling GI symptoms, and improving skin symptoms

- Aspirin can be used when H1 receptor blockers are ineffective

- Corticosteroids have been used to control malabsorption, ascites, and bone pain and to prevent anaphylaxis

- Patients with osteopenia that does not respond to therapy may receive a trial of interferon alfa-2b

- Leukotriene antagonists (eg, zafirlukast, montelukast) have been used

- Psoralen ultraviolet A therapy may provide transient relief of pruritus and may cause fading of skin lesions

Chemotherapy has not been particularly successful in the management of systemic mastocytosis, but the following regimens have been tried, in particular as bridging treatment in patients who plan to undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [12] :

- Interferon-alfa may be beneficial, especially in patients with aggressive systemic mastocytosis

- Cladribine

- Hydroxyurea in advanced disease

The following agents are used for treatment of primary disease:

- Midostaurin (Rydapt) is approved by the FDA for use in advanced systemic mastocytosis (ASM, SM-AHN, MCL) [13]

- Avapritinib (Ayvakit) is approved for use in adults with advanced systemic mastocytosis [14] and indolent systemic mastocytosis [15]

- Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) is used in patients who do not have mutations of codon 816 on the c-kit gene and carry the wild-type kit, or who carry the FIP1L1-PDGFRA rearrangement. [16]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

For patient education information, see Systemic Mastocytosis.

Background

Systemic mastocytosis is a heterogeneous clonal disorder of the mast cell and its precursor cells. The clinical symptoms and signs of systemic mastocytosis result from mediator release and the accumulation of these clonally derived mast cells in different tissues, including bone marrow, skin, the GI tract, the liver, and the spleen. [1, 2, 17, 3]

Systemic mastocytosis is characterized by mast cell infiltration of extracutaneous organs, which is in contrast to cutaneous mast cell disorders, which involve only the skin. Ehrlich first described mast cells in 1877 when he found cells that stained metachromatically with aniline dyes. [18] He called these cells "mast Zellen" because the cells were distended with granules (ie, the botanical definition of mast, which refers to an accumulation of nuts on the forest floor).

Cutaneous mastocytosis was identified in the late 19th century. Sangster first described urticaria pigmentosa, which is one of the cutaneous mast cell disorders, in 1878. In 1933, Touraine suggested that this disease could involve internal organs. In 1949, Ellis first established at autopsy that cutaneous mastocytosis can also involve internal organs. An autopsy of a 1-year-old infant revealed mast cell infiltration of the bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, kidneys, and pancreas.

Pathophysiology

Systemic mastocytosis (systemic mast cell disease) is characterized by mast cell infiltration of skin and extracutaneous organs. Mast cells typically infiltrate the bone marrow and consequently affect the peripheral blood and coagulation system. [19] Mast cells are derived from CD34+/ KIT+ pluripotent hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. [20] The neoplastic clones of mast cells express abnormal cell surface markers CD25 and/or CD2.

Mueller et al reported that the adhesion molecule CD44 is expressed in systemic mastocytosis cell lines and correlates with the aggressiveness of the disorder. They found that serum levels of soluble CD44 were higher in advanced systemic mastocytosis compared with indolent systemic mastocytosis or cutaneous mastocytosis, and correlated with overall and progression-free survival. [21]

The marrow cellularity ranges from normocellular to markedly hypercellular changes. Erythropoiesis is usually normoblastic without any significant abnormalities. Eosinophilia is a common bone marrow histology finding (see Workup, Histologic Findings). Hypocellular bone marrow and myelofibrosis can be observed in late stages of systemic mastocytosis.

Ho et al evaluated the plasma level of pro–major basic protein (proMBP), a precursor of major basic protein that is contained in eosinophil cytoplasmic granules, in eosinophilic and chronic myeloproliferative disorders. [22] They found that the plasma proMBP level was significantly higher in patients with systemic mastocytosis with eosinophilia, idiopathic eosinophilia, and myeloproliferative disorders with eosinophilia than in healthy controls. In addition, the median proMBP level of patients with postpolycythemic myeloid metaplasia and those with postthrombocythemic myeloid metaplasia was significantly higher than in those with polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. [22]

Ho et al also reported that the presence and size of splenomegaly correlated with proMBP levels in certain conditions. In patients with idiopathic eosinophilia, the presence of splenomegaly was significantly associated with elevated proMBP. [22] In 76 patients with de novo myelofibrosis, the proMBP level correlated with spleen size and the presence of hypercatabolic symptoms. All of these findings led the investigators to conclude that "significantly elevated levels of proMBP in myelofibrosis patients implies that proMBP could be an important stromal cytokine in bone marrow fibrosis." [22]

Focal mast cell lesions in the bone marrow are found in approximately 90% of adult patients with systemic mastocytosis. A typical mast cell has a spindle-shaped nucleus and fine eosinophilic granules, which can be visualized at high magnification. These cells are likely to return positive findings upon Giemsa staining. Peripheral blood can show anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia. The most common abnormality found in the peripheral blood is anemia. In some patients, eosinophilia, leukocytosis, basophilia, thrombocytosis, and monocytosis can be observed.

Spleen and lymphoid tissue involvement is a significant manifestation of systemic mastocytosis. Mast cell infiltrates in the spleen can cause nodular areas that could be confused with lymphomas. A biopsy specimen from the spleen can reveal findings similar to a myeloproliferative disorder or hairy cell leukemia. Histopathology studies of the spleen can reveal two types of involvement: (1) diffuse infiltration of the red pulp and sinuses and (2) focal infiltration of the white pulp. Lymph node biopsy can show mast cell infiltrates, particularly in the paracortex. Follicles and medullary involvement can be observed in some cases.

The immune system is affected as a consequence of the previously mentioned pathology. Mast cell products, such as interleukin 4 (IL-4) and IL-3, may induce immunoglobulin E (IgE) synthesis and augment T-cell differentiation toward an allergic phenotype. Mast cells also release histamine, which results in inhibition of IL-2.

GI manifestations result from microscopic infiltration of the liver, pancreas, and intestines by mast cells. [23, 24] Abdominal pain has been attributed to peptic ulcer disease, involvement of the GI tract by mast cells, mediators released by mast cells, and motility disorders. GI involvement includes the following:

- Esophagus (eg, esophagitis, stricture, varices)

- Stomach (eg, peptic ulcer disease, mucosal lesions)

- Small intestine (eg, dilatated small bowel, malabsorption)

- Colon and rectum (eg, multiple polyposis, diverticulitis)

- Liver (eg, hepatomegaly and portal hypertension, ascites, sclerosing cholangitis, Budd-Chiari syndrome)

Osteoporosis is a common manifestations of systemic mastocytosis, particularly in adults, and can result in vertebral fractures. The mechanism of bone loss is not yet fully elucidated, but stimulation of osteoclast activity through RANK-RANKL signaling appears to be most important. Histamine and other cytokines also play significant roles. [25]

Systemic mastocytosis has many features in common with myeloproliferative disorders. However, the 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia no longer lists mastocytosis under the broad heading of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), and instead assigns it to a separate category. [11]

More than 95% of adults with systemic mastocytosis have exon 17 KIT mutations, most commonly the KIT D816V mutation. This gain of function mutation in the KIT receptor was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques in 68% of bone marrow specimens in patients with systemic mastocytosis. [8] Additional molecular aberrations are frequently identified in TET2, SRSF2, ASXL1, CBL, RUNX1, DNMT3A, and in the RAS pathway. [26]

The association between JAK2 V617F and systemic mastocytosis is weak and was noted in just 4% of patients with systemic mastocytosis (all had associated non–mast cell hematological disease). [8] The incidence of TET2 mutations (reportedly as high as 29% in KIT-positive systemic mastocytosis) seems to influence the phenotype without affecting the prognosis. [27] Another finding that may prove relevant to the pathogenesis of systemic mastocytosis is a constitutive expression of the stress-related survival factor heat-shock protein 32 (Hsp32) in a human mast cell tumor line. [28]

Etiology

Mutations of the c-kit proto-oncogene may cause some forms of mastocytosis. [29, 30, 24] Mutations of c-kit in mast cell tumor lines and the ability of c-kit to cause mast cell proliferation and transformation suggest that these mutations are necessary in most forms of mastocytosis.

Several types of somatic activating and nonactivating mutations in c-kit have been demonstrated to cause systemic mastocytosis. One of the common mutations found in systemic mastocytosis is an exon 17 D816V KIT receptor mutation. Most, if not all, adult patients with systemic mastocytosis carry this mutation. [31] In the majority of patients, mastocytosis does not appear to be inherited, but rare familial cases with KIT mutations have been reported.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Systemic mastocytosis is an extremely rare disorder in the United States; the specific incidence has not been reported. Likewise, epidemiologic data on the incidence of systemic mastocytosis are lacking. Some studies in Great Britain showed two cases per year from a study population of 300,000.

Mortality/morbidity

Systemic mastocytosis is a progressive neoplastic disorder that has no known curative therapy. Survival in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis, with a median survival of 198 months, is not significantly different from the general population. However, median survival with aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM) is 41 months and that with systemic mastocytosis with associated hematological non–mast cell disorder (SM-AHNMD) is 24 months. Acute mast cell leukemia has the poorest prognosis, with a median survival of 2 months.

Early evolution into acute leukemia may occur in as many as 32% of patients with aggressive mastocytosis. [17] Leukemic transformation is rare with indolent systemic mastocytosis. [8]

Sex- and age-related demographics

A slight male preponderance in the incidence of mastocytosis is noted. [8] Mastocytosis is more common in children than in adults, and it is usually transient and self-limited in children compared with the adult version. Onset is before age 2 years in 55% of patients and is from 2 and 15 years in 10% of patients.

In pediatric patients, progression of cutaneous mastocytosis to systemic mastocytosis is uncommon. In adults, however, cutaneous mastocytosis frequently progresses to systemic disease. [3]

In adults, the median age at diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis is 55 years. Lim et al reported that patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis were younger and symptomatic for a longer duration of time as compared with patients with ASM or SM-AHNMD. [8]

Prognosis

The prognosis in patients with systemic mastocytosis (systemic mast cell disease) is variable. [32] Several prognostic models for systemic mastocytosis have been developed, but there is no consensus regarding the preferred approach for defining prognosis. Young children and patients who present with primarily cutaneous and flushing manifestations tend to have little or no progression of the disease over a considerable length of time. However, older patients and those with more extensive systemic disease involving organ systems other than the skin have a poorer prognosis [33] ; although their median duration of survival is not known, it appears to be a few years.

On laboratory studies, elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels are a poor prognostic sign. [33] On multivariate analysis, the following findings have also been shown to portend poor prognosis [8] :

- Anemia (hemoglobin < 10.0 mg/dL)

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 150,000/μ L)

- Hypoalbuminemia (albumin < 3.5 g/dL)

- Excess bone marrow blasts (>5%)

In 2019, Jawhar et al published a validated five-parameter mutation-adjusted risk score (MARS) that defines three risk groups among patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis, which may improve up-front treatment stratification. [34] The MARS parameters and assigned points are as follows

- Age > 60 years – 1 point

- Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL) – 1 point

- Platelet count < 100 × 109/L) – 1 point

- Presence of one high molecular risk gene mutation (ie, in SRSF2, ASXL1, and/or RUNX1 – 1 point

- Presence of two or more high molecular risk gene mutations – 2 points

These weighted scores are used to classify patients into one of the following three risk categories:

- Low risk: 0 to 1 point

- Intermediate risk: 2 points

- High risk: 3 - 5 points

Median overall survival (OS) in the three risk categories were as follows:

- Low risk - Median OS not reached

- Intermediate risk - Median OS 3.9 years (95% CI, 2.1 to 5.7 years)

- High risk - Median OS 1.9 years (95% CI, 1.3 to 2.6 years

Patient Education

Given the risk of anaphylactoid reactions, patients should carry epinephrine-filled syringes at all times and should be taught to administer epinephrine in cases of emergency.

For patient education information, see Systemic Mastocytosis.

- Lee HJ. Recent advances in diagnosis and therapy in systemic mastocytosis. Blood Res. 2023 Apr 30. 58 (S1):96-108. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gangireddy M, Ciofoaia GA. Systemic Mastocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2023 Jan. 106(1):9-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Horny HP, Arock M, Metcalfe DD, et al. New Insights into the Pathogenesis of Mastocytosis: Emerging Concepts in Diagnosis and Therapy. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023 Jan 24. 18:361-386. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bonadonna P, Zanotti R, Pagani M, Caruso B, Perbellini O, Colarossi S. How much specific is the association between hymenoptera venom allergy and mastocytosis?. Allergy. 2009 Sep. 64(9):1379-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Weingarten TN, Volcheck GW, Sprung J. Anaphylactoid reaction to intravenous contrast in patient with systemic mastocytosis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009 Jul. 37(4):646-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moura DS, Georgin-Lavialle S, Gaillard R, Hermine O. Neuropsychological features of adult mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014 May. 34 (2):407-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van der Veer E, van der Goot W, de Monchy JG, Kluin-Nelemans HC, van Doormaal JJ. High prevalence of fractures and osteoporosis in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis. Allergy. 2012 Mar. 67 (3):431-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lim KH, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, et al. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009 Jun 4. 113(23):5727-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schwartz LB, Irani AM. Serum tryptase and the laboratory diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000 Jun. 14(3):641-57. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022 Jul. 36 (7):1703-1719. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016 May 19. 127 (20):2391-405. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ustun C, Corless CL, Savage N, et al. Chemotherapy and dasatinib induce long-term hematologic and molecular remission in systemic mastocytosis with acute myeloid leukemia with KIT D816V. Leuk Res. 2009 May. 33(5):735-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, Akin C, Sotlar K, Hermine O, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Midostaurin in Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 30. 374 (26):2530-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- FDA Approves Avapritinib for Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. The ASCO Post. Available at https://ascopost.com/news/june-2021/fda-approves-avapritinib-for-advanced-systemic-mastocytosis/?utm_source=TAP%2DEN%2D061721%2DTrending%5FHeme&utm_medium=email&utm_term=046fca8ed7062b1f9d17ba521501b8c9?bc_md5=046fca8ed7062b1f9d17ba521501b8c9. June 17, 2021; Accessed: June 21, 2021.

- FDA Approves Avapritinib for Indolent Systemic Mastocytosis. The ASCO Post. Available at https://ascopost.com/news/may-2023/fda-approves-avapritinib-for-indolent-systemic-mastocytosis/?utm_source=TAP%2DEN%2D052323&utm_medium=email&utm_term=046fca8ed7062b1f9d17ba521501b8c9. May 23, 2023; Accessed: May 23, 2023.

- Pardanani A, Ketterling RP, Brockman SR, et al. CHIC2 deletion, a surrogate for FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion, occurs in systemic mastocytosis associated with eosinophilia and predicts response to imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood. 2003 Nov 1. 102(9):3093-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Pieri L, Bonadonna P, Elena C, Papayannidis C, Grifoni FI, et al. Clinical presentation and management practice of systemic mastocytosis. A survey on 460 Italian patients. Am J Hematol. 2016 Apr 7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ehrlich P. Beitrage zur Kenntnis der Anilinfarbungen und ihrer Verwendung in der mikroskopischen Technik. Arch mikr Anat. 1877. 13:263-7.

- Parker RI. Hematologic aspects of systemic mastocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000 Jun. 14(3):557-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kirshenbaum AS, Goff JP, Semere T, Foster B, Scott LM, Metcalfe DD. Demonstration that human mast cells arise from a progenitor cell population that is CD34(+), c-kit(+), and expresses aminopeptidase N (CD13). Blood. 1999 Oct 1. 94(7):2333-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mueller N, Wicklein D, Eisenwort G, Jawhar M, Berger D, Stefanzl G, et al. CD44 is a RAS/STAT5-regulated invasion receptor that triggers disease expansion in advanced mastocytosis. Blood. 2018 Jul 17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ho CL, Kito H, Squillace DL, Lasho TL, Tefferi A. Clinical correlates of serum pro-major basic protein in a spectrum of eosinophilic disorders and myelofibrosis. Acta Haematol. 2008. 120(3):158-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal abnormalities and involvement in systemic mastocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000 Jun. 14(3):579-623. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kirsch R, Geboes K, Shepherd NA, et al. Systemic mastocytosis involving the gastrointestinal tract: clinicopathologic and molecular study of five cases. Mod Pathol. 2008 Dec. 21(12):1508-16. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rossini M, Zanotti R, Orsolini G, Tripi G, Viapiana O, Idolazzi L, et al. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment options for mastocytosis-related osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2016 Feb 18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schwaab J, Schnittger S, Sotlar K, Walz C, Fabarius A, Pfirrmann M, et al. Comprehensive mutational profiling in advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2013 Oct 3. 122 (14):2460-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tefferi A, Levine RL, Lim KH, Abdel-Wahab O, Lasho TL, Patel J, et al. Frequent TET2 mutations in systemic mastocytosis: clinical, KITD816V and FIP1L1-PDGFRA correlates. Leukemia. 2009 May. 23(5):900-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kondo R, Gleixner KV, Mayerhofer M, Vales A, Gruze A, Samorapoompichit P, et al. Identification of heat shock protein 32 (Hsp32) as a novel survival factor and therapeutic target in neoplastic mast cells. Blood. 2007 Jul 15. 110 (2):661-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ma Y, Zeng S, Metcalfe DD, et al. The c-KIT mutation causing human mastocytosis is resistant to STI571 and other KIT kinase inhibitors; kinases with enzymatic site mutations show different inhibitor sensitivity profiles than wild-type kinases and those with regulatory-type mutations. Blood. 2002 Mar 1. 99(5):1741-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Pardanani A, Elliott M, Reeder T, et al. Imatinib for systemic mast-cell disease. Lancet. 2003 Aug 16. 362(9383):535-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garcia-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, Teodosio C, Sanchez ML, Nunez R, Prados A, et al. KIT mutation in mast cells and other bone marrow hematopoietic cell lineages in systemic mast cell disorders: a prospective study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) in a series of 113 patients. Blood. 2006 Oct 1. 108(7):2366-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lim KH, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, et al. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009 Jun 4. 113(23):5727-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pardanani A, Lim KH, Lasho TL, et al. Prognostically relevant breakdown of 123 patients with systemic mastocytosis associated with other myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2009 Oct 29. 114(18):3769-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jawhar M, Schwaab J, Álvarez-Twose I, et al. MARS: Mutation-Adjusted Risk Score for Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Nov 1. 37 (31):2846-2856. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Butterfield JH. Survey of aspirin administration in systemic mastocytosis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009 Apr. 88(3-4):122-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mital A, Prejzner W, Hellmann A. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome during the course of systemic mastocytosis - analysis of 21 cases. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2018 Jul 11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Jawhar M, Schwaab J, Horny HP, Sotlar K, Naumann N, Fabarius A, et al. Impact of Centralized Evaluation of Bone Marrow Histology in Systemic Mastocytosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016 Feb 23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Donker ML, van Doormaal JJ, van Doormaal FF, Kluin PM, van der Veer E, de Monchy JG, et al. Biochemical markers predictive for bone marrow involvement in systemic mastocytosis. Haematologica. 2008 Jan. 93 (1):120-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lueke AJ, Meeusen JW, Donato LJ, Gray AV, Butterfield JH, Saenger AK. Analytical and clinical validation of an LC-MS/MS method for urine leukotriene E4: A marker of systemic mastocytosis. Clin Biochem. 2016 Feb 18. 264 (1):217-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gilreath JA, Tchertanov L, Deininger MW. Novel approaches to treating advanced systemic mastocytosis. Clin Pharmacol. 2019. 11:77-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Horny HP. Mastocytosis: an unusual clonal disorder of bone marrow-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009 Sep. 132(3):438-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jawhar M, Schwaab J, Horny HP, Sotlar K, Naumann N, Fabarius A, et al. Impact of Centralized Evaluation of Bone Marrow Histology in Systemic Mastocytosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016 Feb 23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hahn HP, Hornick JL. Immunoreactivity for CD25 in gastrointestinal mucosal mast cells is specific for systemic mastocytosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007 Nov. 31 (11):1669-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. 2022 Sep 15. 140 (11):1200-1228. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Worobec AS. Treatment of systemic mast cell disorders. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000 Jun. 14(3):659-87, vii. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gangireddy M, Ciofoaia GA. Systemic Mastocytosis. 2023 Jan. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Cardet JC, Akin C, Lee MJ. Mastocytosis: update on pharmacotherapy and future directions. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013 Oct. 14 (15):2033-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Pitt TJ, Cisneros N, Kalicinsky C, Becker AB. Successful treatment of idiopathic anaphylaxis in an adolescent. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Aug. 126 (2):415-6; author reply 416. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Slapnicar C, Trinkaus M, Hicks L, Vadas P. Efficacy of Omalizumab in Indolent Systemic Mastocytosis. Case Rep Hematol. 2019. 2019:3787586. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- McComish JS, Slade CA, Buizen L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of omalizumab in treatment-resistant systemic and cutaneous mastocytosis (ROAM). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 Apr 23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Sacta MA, Alsaati N, Spergel J. Anaphylaxis: A 2023 practice parameter update: Major changes in management of anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024 Feb. 132 (2):109-110. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- van der Veer E, van der Goot W, de Monchy JG, Kluin-Nelemans HC, van Doormaal JJ. High prevalence of fractures and osteoporosis in patients with indolent systemic mastocytosis. Allergy. 2012 Mar. 67(3):431-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Radia D, Deininger M, Gotlib J, et al. Avapritinib, a potent and selective inhibitor of KIT D816V, induces complete and durable responses in patients (pts) with advanced systemic mastocytosis (AdvSM). European Hematology Association. Available at https://library.ehaweb.org/eha/2019/24th/267413/deepti.radia.avapritinib.a.potent.and.selective.inhibitor.of.kit.d816v.induces.html?f=listing%3D3%2Abrowseby%3D8%2Asortby%3D1%2Amedia%3D1. June 15, 2019; Accessed: June 22, 2020.

- Gotlib J, Castells M, Elberink HO, Siebenhaar F, Hartmann K, Broesby-Olsen S, et al. Avapritinib versus placebo in indolent systemic mastocytosis. NEJM Evid. 2023 May 23. 2(6):[Full Text].

- Lee HJ. Recent advances in diagnosis and therapy in systemic mastocytosis. Blood Res. 2023 Apr 30. 58 (S1):96-108. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Valent P, Sperr WR, Akin C. How I treat patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis. Blood. 2010 Dec 23. 116 (26):5812-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2021 Update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. Am J Hematol. 2021 Apr 1. 96 (4):508-525. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Systemic Mastocytosis Version 1.2023. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mastocytosis.pdf. May 24, 2023; Accessed: May 28, 2023.

- Gruson B, Lortholary O, Canioni D, Chandesris O, Lanternier F, Bruneau J, et al. Thalidomide in systemic mastocytosis: results from an open-label, multicentre, phase II study. Br J Haematol. 2013 May. 161 (3):434-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yacoub A, Prochaska L. Ruxolitinib improves symptoms and quality of life in a patient with systemic mastocytosis. Biomark Res. 2016. 4:2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Dowse R, Ibrahim M, McLornan DP, Moonim MT, Harrison CN, Radia DH. Beneficial effects of JAK inhibitor therapy in Systemic Mastocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2016 Feb 5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ustun C, Reiter A, Scott BL, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for advanced systemic mastocytosis. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Oct 10. 32 (29):3264-74. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chaar CI, Bell RL, Duffy TP, Duffy AJ. Guidelines for safe surgery in patients with systemic mastocytosis. Am Surg. 2009 Jan. 75(1):74-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Alvarez-Twose I, Matito A, Morgado JM, Sánchez-Muñoz L, Jara-Acevedo M, García-Montero A, et al. Imatinib in systemic mastocytosis: a phase IV clinical trial in patients lacking exon 17 KIT mutations and review of the literature. Oncotarget. 2017 Sep 15. 8 (40):68950-68963. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Coauthor(s)

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Ronald A Sacher, MD, FRCPC, DTM&H Professor Emeritus of Internal Medicine and Hematology/Oncology, Emeritus Director, Hoxworth Blood Center, University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center

Ronald A Sacher, MD, FRCPC, DTM&H is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Association of Blood Banks, American Clinical and Climatological Association, American Society for Clinical Pathology, American Society of Hematology, College of American Pathologists, International Society of Blood Transfusion, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Emmanuel C Besa, MD Professor Emeritus, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematologic Malignancies and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, Kimmel Cancer Center, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University

Emmanuel C Besa, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for Cancer Education, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American College of Clinical Pharmacology, American Federation for Medical Research, American Society of Hematology, New York Academy of Sciences

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Koyamangalath Krishnan, MD, FRCP, FACP Dishner Endowed Chair of Excellence in Medicine, Professor of Medicine, James H Quillen College of Medicine at East Tennessee State University

Koyamangalath Krishnan, MD, FRCP, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, American Society of Hematology, Royal College of Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Thomas H Davis, MD, FACP Associate Professor, Fellowship Program Director, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Hematology/Oncology, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth

Thomas H Davis, MD, FACP is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Association for Cancer Education, American College of Physicians, New Hampshire Medical Society, Phi Beta Kappa, Society of University Urologists

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors and editors of Medscape Reference gratefully acknowledge the contributions of previous authors Stephen J Smith, MD, Harsha G Vardhana, MD, and Guha Krishnaswamy, MD, to the development and writing of this article.