Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. It usually presents as bilateral symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that affects the hands and feet (see the image below). Any joint lined by a synovial membrane may be affected, however, and extra-articular involvement of organs such as the skin, heart, lungs, and eyes can be significant. RA is theorized to develop when a genetically susceptible individual (eg, a carrier of HLA-DR4 or HLA-DR1 [1] ) experiences an external factor (eg, cigarette smoking, infection, trauma) that triggers an autoimmune reaction.

Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid changes in the hand. Photograph by David Effron MD, FACEP.

Signs and symptoms

In most patients with RA, onset is insidious, often beginning with fever, malaise, arthralgias, and weakness before progressing to joint inflammation and swelling. Signs and symptoms of RA may include the following:

- Persistent symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) of hands and feet (hallmark feature)

- Progressive articular deterioration

- Extra-articular involvement

- Difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs)

- Constitutional symptoms

The physical examination should address the following:

- Upper extremities (metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists, elbows, shoulders)

- Lower extremities (ankles, feet, knees, hips)

- Cervical spine

During the physical examination, it is important to assess the following:

- Stiffness

- Tenderness

- Pain on motion

- Swelling

- Deformity

- Limitation of motion

- Extra-articular manifestations

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

No test results are pathognomonic; instead, the diagnosis is made by using a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging features. Potentially useful laboratory studies in suspected RA include the following:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- C-reactive protein level

- Complete blood count

- Rheumatoid factor assay

- Antinuclear antibody assay

- Anti−cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody

Potentially useful imaging modalities include the following:

- Radiography (first choice): Hands, wrists, knees, feet, elbows, shoulders, hips, cervical spine, and other joints as indicated

- Magnetic resonance imaging: Primarily cervical spine

- Ultrasonography of joints: Joints, as well as tendon sheaths, for assessment of changes and degree of vascularization of the synovial membrane, and even erosions

Joint aspiration and analysis of synovial fluid may be considered, including the following:

- Gram stain

- Cell count

- Culture

- Assessment of overall appearance

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of RA should be initiated early, using shared decision making, an integrated approach that includes both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies, and a treat-to-target strategy. Treating to target is facilitated by use of the following:

- American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommended RA disease activity measures [2]

- ACR/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) criteria for remission [3]

Nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical therapies include the following:

- Heat and cold therapies

- Orthotics and splints

- Therapeutic exercise

- Occupational therapy

- Adaptive equipment

- Joint-protection education

- Energy-conservation education

The following organizations have published guidelines for pharmacologic therapy:

- American College of Rheumatology (2021) [4]

- European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (2022) [5]

Nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) include the following:

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Azathioprine

- Sulfasalazine

- Methotrexate

- Leflunomide

- Cyclosporine

- Gold salts

- D-penicillamine

- Minocycline

Biologic tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–inhibiting DMARDs include the following:

- Etanercept

- Infliximab

- Adalimumab

- Certolizumab

- Golimumab

Biologic non-TNF DMARDs include the following:

- Rituximab

- Anakinra

- Abatacept

- Tocilizumab

- Sarilumab

- Tofacitinib

- Baricitinib

- Upadacitinib

Other drugs used therapeutically include the following:

- Corticosteroids

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Analgesics

Surgical treatments include the following:

- Synovectomy

- Tenosynovectomy

- Tendon realignment

- Reconstructive surgery or arthroplasty

- Arthrodesis

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The hallmark feature of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is persistent symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that affects the hands and feet, though any joint lined by a synovial membrane may be involved. Extra-articular involvement of organs such as the skin, heart, lungs, and eyes can be significant. (See Presentation.)

No laboratory test results are pathognomonic for RA, but the presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA; often tested as anti-CCP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) is highly specific for this condition. (See Workup.)

Optimal care of patients with RA requires an integrated approach that includes nonpharmacologic therapies and pharmacologic agents such as nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, and corticosteroids. (See Treatment, Guidelines, and Medication.)

Early therapy with DMARDs has become the standard of care; it not only can more efficiently retard disease progression than later treatment but also may induce more remissions. (See Treatment and Guidelines.) Many of the newer DMARD therapies, however, are immunosuppressive in nature, leading to a higher risk for infections. (See Treatment/Complications.)

Macrophage activation syndrome is a life-threatening complication of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) that necessitates immediate treatment with high-dose steroids and cyclosporine. (See Complications.)

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of RA is not completely understood. An external trigger (eg, cigarette smoking, infection, or trauma) that sets off an autoimmune reaction, leading to synovial hypertrophy and chronic joint inflammation along with the potential for extra-articular manifestations, is theorized to occur in genetically susceptible individuals.

The onset of clinically apparent RA is preceded by a period of pre-rheumatoid arthritis (pre-RA). The development of pre-RA and its progression to established RA has been categorized into the following phases [6] :

- Phase I - Interaction between genetic and environmental risk factors of RA

- Phase II - Production of RA autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP)

- Phase III - Development of arthralgia or joint stiffness without any clinical evidence of arthritis

- Phase IV – Development of arthritis in one or two joints (ie, early undifferentiated arthritis); if intermittent, the arthritis at this stage is termed palindromic rheumatism

- Phase V - Established RA

Not all individuals will progress through the full sequence of phases, and current research is investigating ways to identify patients who are at risk of progression, and to delay or prevent RA in those patients. [7]

Synovial cell hyperplasia and endothelial cell activation are early events in the pathologic process that progresses to uncontrolled inflammation and consequent cartilage and bone destruction. Genetic factors and immune system abnormalities contribute to disease propagation.

CD4 T cells, mononuclear phagocytes, fibroblasts, osteoclasts, and neutrophils play major cellular roles in the pathophysiology of RA, and B cells produce autoantibodies (ie, rheumatoid factors). Abnormal production of numerous cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators has been demonstrated in patients with RA, including the following:

- Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)

- Interleukin (IL)-1

- IL-6

- IL-8

- Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-ß)

- Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)

- Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)

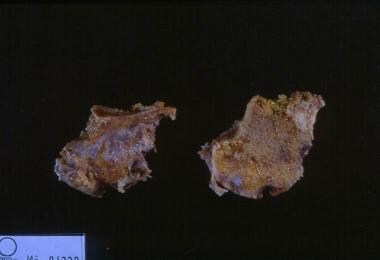

Ultimately, inflammation and exuberant proliferation of the synovium (ie, pannus) leads to destruction of various tissues, including cartilage (see the image below), bone, tendons, ligaments, and blood vessels. Although the articular structures are the primary sites involved by RA, other tissues are also affected.

Rheumatoid arthritis. This gross photo shows destruction of the cartilage and erosion of the underlying bone with pannus from a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

Etiology

The cause of RA is unknown. Genetic, environmental, hormonal, immunologic, and infectious factors may play significant roles. Socioeconomic, psychological, and lifestyle factors may influence disease development and outcome.

Genetic factors

Genetic factors account for 50% of the risk for developing RA. [8] About 60% of RA patients in the United States carry a shared epitope of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4 cluster, which constitutes one of the peptide-binding sites of certain HLA-DR molecules associated with RA (eg, HLA-DR beta *0401, 0404, or 0405). HLA-DR1 (HLA-DR beta *0101) also carries this shared epitope and confers risk, particularly in certain southern European areas. Other HLA-DR4 molecules (eg, HLA-DR beta *0402) lack this epitope and do not confer this risk.

Genes other than those of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are also involved. Results from sequencing genes of families with RA suggest the presence of several resistance and susceptibility genes, including PTPN22 and TRAF5. [9, 10] Researchers have identified more than 150 candidate loci with polymorphisms associated with RA, mainly related to seropositive disease. [11]

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), also known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), is a heterogeneous group of diseases that differs markedly from adult RA. JIA is known to have genetically complex traits in which multiple genes are important for disease onset and manifestations, and it is characterized by arthritis that begins before the age of 16 years, persists for more than 6 weeks, and is of unknown origin. [12] The IL2RA/CD25 gene has been implicated as a JIA susceptibility locus, as has the VTCN1 gene. [13]

Some investigators suggest that the future of treatment and understanding of RA may be based on imprinting and epigenetics. RA is significantly more prevalent in women than in men, [14, 15] which suggests that genomic imprinting from parents participates in its expression. [16, 17] Imprinting is characterized by differential methylation of chromosomes by the parent of origin, resulting in differential expression of maternal over paternal genes. [18]

Epigenetics is the change in DNA expression that is due to environmentally induced methylation and not to a change in DNA structure. Clearly, one research focus will be on environmental factors in combination with immune genetics. [11]

Infectious agents

For many decades, numerous infectious agents have been suggested as potential causes of RA, including Mycoplasma organisms, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), [19] and rubella virus. This suggestion is indirectly supported by the following evidence:

- Occasional reports of flulike disorders preceding the start of arthritis

- The inducibility of arthritis in experimental animals with different bacteria or bacterial products (eg, streptococcal cell walls)

- The presence of bacterial products, including bacterial RNA, in patients’ joints

- The disease-modifying activity of several agents that have antimicrobial effects (eg, gold salts, antimalarial agents, minocycline)

Emerging evidence also points to an association between RA and periodontopathic bacteria. For example, the synovial fluid of RA patients has been found to contain high levels of antibodies to anaerobic bacteria that commonly cause periodontal infection, including Porphyromonas gingivalis. [20, 21]

Hormonal factors

Sex hormones may play a role in RA, as evidenced by the disproportionate number of females with this disease, its amelioration during pregnancy, its recurrence in the early postpartum period, and its reduced incidence in women using oral contraceptives. Hyperprolactinemia may be a risk factor for RA. [22]

Lifestyle and occupational factors

Tobacco use is the main lifestyle risk factor for RA. [23] Genetic factors can further increase risk: a smoker with two copies of HLA-SE is at 40-fold higher risk of developing RA. In former smokers, risk may not return to the level of non-smokers for up to 20 years after smoking cessation. [6]

Dietary risk factors for RA include the following [6] :

- Red meat intake

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Excessive coffee consumption

- High salt intake

A review of data from the Nurses' Health Study, which assessed 5 lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical activity, and diet), found that a healthier lifestyle was associated with lower risk of RA. The population attributable risk estimate was that 34% of incident RA was preventable if participants adopted ≥4 healthy lifestyle factors. [24]

Occupational risk

Schmajuk et al reported a strong association between coal mining, and other dusty trades involving silica exposure, with RA. For those in the highest-intensity ergonomic exposure group, the odds ratio for RA was 4.3. [25]

Immunologic factors

All of the major immunologic elements play fundamental roles in initiating, propagating, and maintaining the autoimmune process of RA. The exact orchestration of the cellular and cytokine events that lead to pathologic consequences (eg, synovial proliferation and subsequent joint destruction) is complex, involving T and B cells, antigen-presenting cells (eg, B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells), and various cytokines. Aberrant production and regulation of both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and cytokine pathways are found in RA.

T cells are assumed to play a pivotal role in the initiation of RA, and the key player in this respect is assumed to be the T helper 1 (Th1) CD4 cells. (Th1 cells produce IL-2 and interferon [IFN] gamma.) These cells may subsequently activate macrophages and other cell populations, including synovial fibroblasts. Macrophages and synovial fibroblasts are the main producers of TNF-a and IL-1. Experimental models suggest that synovial macrophages and fibroblasts may become autonomous and thus lose responsiveness to T-cell activities in the course of RA.

B cells are important in the pathologic process and may serve as antigen-presenting cells. B cells also produce numerous autoantibodies (eg, RF and ACPA) and secrete cytokines.

The hyperactive and hyperplastic synovial membrane is ultimately transformed into pannus tissue and invades cartilage and bone, with the latter being degraded by activated osteoclasts. The major difference between RA and other forms of inflammatory arthritis, such as psoriatic arthritis, lies not in their respective cytokine patterns but, rather, in the highly destructive potential of the RA synovial membrane and in the local and systemic autoimmunity.

Whether these 2 events are linked is unclear; however, the autoimmune response conceivably leads to the formation of immune complexes that activate the inflammatory process to a much higher degree than normal. This theory is supported by the much worse prognosis of RA among patients with positive RF results.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, the annual incidence of RA is approximately 3 cases per 10,000 population, and the prevalence rate is approximately 1%, increasing with age and peaking between the ages of 35 and 50 years. RA affects all populations, though it is much more prevalent in some groups (eg, 5-6% in some Native American groups) and much less prevalent in others (eg, Black persons from the Caribbean region).

First-degree relatives of individuals with RA are at 2- to 3-fold higher risk for the disease. Disease concordance in monozygotic twins is approximately 15-20%, suggesting that nongenetic factors play an important role. Because the worldwide frequency of RA is relatively constant, a ubiquitous infectious agent has been postulated to play an etiologic role.

Women are affected by RA approximately 3 times more often than men are. [14, 15] For example, a nationwide study from Norway reported that the point prevalence of RAl was 1.10% in women and 0.46% in men. [26] However, sex differences in RA diminish in older age groups. [14] In investigating whether the higher rate of RA among women could be linked to certain reproductive risk factors, a study from Denmark found that the rate of RA was higher in women who had given birth to just 1 child than in women who had delivered 2 or 3 offspring. [27] However, the rate was not increased in women who were nulliparous or who had a history of lost pregnancies.

Time elapsed since pregnancy is also significant. In the 1- to 5-year postpartum period, a decreased risk for RA has been recognized, even in those with higher-risk HLA markers. [28]

The Danish study also found a higher risk of RA among women with a history of preeclampsia, hyperemesis during pregnancy, or gestational hypertension. [27] In the authors’ view, this portion of the data suggested that a reduced immune adaptability to pregnancy may exist in women who are predisposed to the development of RA or that there may be a link between fetal microchimerism (in which fetal cells are present in the maternal circulation) and RA. [27]

Prognosis

The clinical course of RA is generally one of exacerbations and remissions. Approximately 40% of patients with this disease become disabled after 10 years, but outcomes are highly variable. [29] Some patients experience a relatively self-limited disease, whereas others have a chronic progressive illness.

Prognostic factors

Outcome in RA is compromised when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Intervention with DMARDs in very early RA (symptom duration < 12 weeks at the time of first treatment) provides the best opportunity for achieving disease remission. [30] Better detection of early joint injury has provided a previously unappreciated view of the ubiquity and importance of early joint damage. Nonetheless, predicting the long-term course of an individual case of RA at the outset remains difficult, though the following all correlate with an unfavorable prognosis in terms of joint damage and disability:

- HLA-DRB1*04/04 genotype

- High serum titer of autoantibodies (eg, RF and ACPA)

- Extra-articular manifestations

- Large number of involved joints

- Age younger than 30 years

- Female sex

- Systemic symptoms

- Insidious onset

In a retrospective study that used logistic regression to analyze clinical and laboratory assessments in patients with RA who took only methotrexate, the authors found that measures of C-reactive protein (CRP) and swollen joint count after 12 weeks of methotrexate administration were most associated with radiographic progression at week 52. [31]

The prognosis of RA is generally much worse among patients with positive RF results. For example, the presence of RF in sera has been associated with severe erosive disease. [32, 33] However, the absence of RF does not necessarily portend a good prognosis.

Other laboratory markers of a poor prognosis include early radiologic evidence of bony injury, persistent anemia of chronic disease, elevated levels of the C1q component of complement, and the presence of ACPA (see Workup). In fact, the presence of ACPA and antikeratin antibodies (AKA) in sera has been linked with severe erosive disease, [32] and the combined detection of these autoantibodies can increase the ability to predict erosive disease in RA patients. [33]

RA that remains persistently active for longer than 1 year is likely to lead to joint deformities and disability. [34] Periods of activity lasting only weeks or a few months followed by spontaneous remission portend a better prognosis.

A study by Mollard et al of 8189 women in a US-wide observational cohort who developed RA before menopause found greater functional decline in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal ones; furthermore, the trajectory of functional decline worsened and accelerated after menopause. However, ever-use of hormonal replacement therapy, ever having a pregnancy, and longer length of reproductive life were associated with less functional decline. [35]

Morbidity and mortality

Most data on RA disability rates derive from specialty units caring for referred patients with severe disease. Little information is available on patients cared for in primary care community settings. Estimates suggest that more than 50% of these patients remain fully employed, even after 10-15 years of disease, with one third having only intermittent low-grade disease and another one third experiencing spontaneous remission.

A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the relative risk of cardiovascular events in patients with RA was 1.55. [36] RA is associated with traditional and nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors. The leading cause of excess mortality in RA is cardiovascular disease, followed by infection, respiratory disease, and malignancies. The effects of concurrent therapy, which is often immunosuppressive, may contribute to mortality in RA. However, studies suggest that control of inflammation may improve survival.

Nontraditional risk factors appear to play an important role in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Myocardial infarction, myocardial dysfunction, and asymptomatic pericardial effusions are common; symptomatic pericarditis and constrictive pericarditis are rare. Myocarditis, coronary vasculitis, valvular disease, and conduction defects are occasionally observed. A large Danish cohort study suggested an increased risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke in patients with RA. [37]

Patients with RA are at significantly elevated risk for lymphoma, likely due to chronic inflammatory stimulation of the immune system. [38] A study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data documented an increased risk for cancer in general in patients with RA. with an odds ratio of 1.632. [39] In contrast, an earlier study of 84,475 RA patients in California concluded that females were at significantly decreased risk for several cancers, including breast, ovary, uterus, cervix, and melanoma, while males had significantly higher risks of lung, liver, and esophageal cancer, but a lower risk of prostate cancer. [40]

The overall mortality in patients with RA is reportedly 2.5 times higher than that of the general age-matched population. In the 1980s, mortality among those with severe articular and extra-articular disease approached that among patients with 3-vessel coronary disease or stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma. Much of the excess mortality derives from infection, vasculitis, and poor nutrition.

Patient Education

Patient education and counseling help to reduce pain and disability and the frequency of physician visits. These may represent the most cost-effective intervention for RA. [41, 42]

Informing patient of diagnosis

With a potentially disabling disease such as RA, the act of informing the patient of the diagnosis takes on major importance. The goal is to satisfy the patient’s informational needs regarding the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment in appropriate detail. To understand the patient’s perspective, requests, and fears, the physician must employ careful questioning and empathic listening.

Telling patients more than they are intellectually or psychologically prepared to handle (a common mistake) risks making the experience so intense as to trigger withdrawal. Conversely, failing to address issues of importance to the patient compromises the development of trust. The patient needs to know that the primary physician understands the situation and is available for support, advice, and therapy as the need arises. Encouraging the patient to ask questions helps to communicate interest and caring.

Discussing prognosis and treatment

Patients and families do best when they know what to expect and can view the illness realistically. Many patients fear crippling consequences and dependency. Accordingly, it is valuable to provide a clear description of the most common disease manifestations. Without encouraging false hopes, the physician can point out that spontaneous remissions can occur, a sizeable portion of patients achieve remission with therapy, and more than two thirds of patients live independently without major disability. In addition, emphasize that much can be done to minimize discomfort and to preserve function.

A review of available therapies and their efficacy helps patients to overcome feelings of depression stemming from an erroneous expectation of inevitable disability. [43] Even in those with severe disease, guarded optimism is now appropriate, given the host of effective and well-tolerated disease-modifying treatments that have become available.

Dealing with misconceptions

Several common misconceptions regarding RA deserve attention. Explaining that no known controllable precipitants exist helps to eliminate much unnecessary guilt and self-recrimination. Dealing in an informative, evidence-based fashion with a patient who expresses interest in alternative and complementary forms of therapy can help limit expenditures on ineffective treatments.

Another misconception is that a medication must be expensive to be helpful. Generic NSAIDs, low-dose prednisone, [29] and the first-line DMARDs are quite inexpensive yet remarkably effective for relieving symptoms, a point that bears emphasizing. The belief that one must be given the latest TNF inhibitor to be treated effectively can be addressed by a careful review of the overall treatment program and the proper role of such agents in the patient’s plan of care.

Active participation of the patient and family in the design and implementation of the therapeutic program helps boost morale and to ensure compliance, as does explaining the rationale for the therapies used.

The family also plays an important part in striking the proper balance between dependence and independence. Household members should avoid overprotecting the patient (eg, the spouse refraining from intercourse out of fear of hurting the patient) and should work to sustain the patient’s pride and ability to contribute to the family. Allowing the patient with RA to struggle with a task is sometimes constructive.

Supporting patient with debilitating disease

Abandonment is a major fear in these individuals. Patients are relieved to know that they will be closely observed by the primary physician and healthcare team, working in conjunction with a consulting rheumatologist and physical/occupational therapist, all of whom are committed to maximizing the patient’s comfort and independence and to preserving joint function. With occupational therapy, the treatment effort is geared toward helping the patient maintain a meaningful work role within the limitations of the illness.

Persons with long-standing severe disease who have already sustained much irreversible joint destruction benefit from an emphasis on comfort measures, supportive counseling, and attention to minimizing further debility. Such patients need help in grieving for their disfigurement and loss of function.

An accepting, unhurried, empathic manner allows the patient to express feelings. The seemingly insignificant act of touching does much to restore a sense of self-acceptance. Attending to pain with increased social support, medication, and a refocusing of attention to function is useful. A trusting and strong patient-doctor relationship can do much to sustain a patient through times of discomfort and disability.

For more information, see the Arthritis Center, as well as Rheumatoid Arthritis, Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Rheumatoid Arthritis Medications.

- Kurkó J, Besenyei T, Laki J, Glant TT, Mikecz K, Szekanecz Z. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis - a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013 Oct. 45 (2):170-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] England BR, Tiong BK, Bergman MJ, Curtis JR, Kazi S, Mikuls TR, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology Recommended Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Measures. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019 Dec. 71 (12):1540-1555. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Studenic P, Aletaha D, de Wit M, Stamm TA, Alasti F, Lacaille D, et al. American College of Rheumatology/EULAR remission criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: 2022 revision. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 Jan. 82 (1):74-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Jul. 73 (7):924-939. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bergstra SA, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023 Jan. 82 (1):3-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Paul BJ, Kandy HI, Krishnan V. Pre-rheumatoid arthritis and its prevention. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017 Jun. 4 (2):161-165. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Deane KD, Holers VM. Rheumatoid Arthritis Pathogenesis, Prediction, and Prevention: An Emerging Paradigm Shift. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Feb. 73 (2):181-193. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barton A, Worthington J. Genetic susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis: an emerging picture. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Oct 15. 61(10):1441-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, et al. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Aug. 75(2):330-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Potter C, Eyre S, Cope A, Worthington J, Barton A. Investigation of association between the TRAF family genes and RA susceptibility. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Oct. 66(10):1322-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Padyukov L. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Immunopathol. 2022 Jan 27. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Prakken B, Albani S, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2011 Jun. 377(9783):2138-49. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hinks A, Ke X, Barton A, Eyre S, Bowes J, Worthington J. Association of the IL2RA/CD25 gene with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jan. 60(1):251-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ahlmen M, Svensson B, Albertsson K, Forslind K, Hafstrom I. Influence of gender on assessments of disease activity and function in early rheumatoid arthritis in relation to radiographic joint damage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Jan. 69(1):230-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Areskoug-Josefsson K, Oberg U. A literature review of the sexual health of women with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2009 Dec. 7(4):219-26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Martin-Trujillo A, van Rietschoten JG, Timmer TC, et al. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 characterises high IGF2 mRNA-expressing type of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Jun. 69(6):1239-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhou X, Chen W, Swartz MD, et al. Joint linkage and imprinting analyses of GAW15 rheumatoid arthritis and gene expression data. BMC Proc. 2007. 1 Suppl 1:S53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barlow DP. Genomic imprinting: a mammalian epigenetic discovery model. Annu Rev Genet. 2011. 45:379-403. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Banko A, Miljanovic D, Lazarevic I, Jeremic I, Despotovic A, Grk M, et al. New Evidence of Significant Association between EBV Presence and Lymphoproliferative Disorders Susceptibility in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Viruses. 2022 Jan 10. 14 (1):[QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hitchon CA, Chandad F, Ferucci ED, et al. Antibodies to porphyromonas gingivalis are associated with anticitrullinated protein antibodies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and their relatives. J Rheumatol. 2010 Jun. 37(6):1105-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Routsias JG, Goules JD, Goules A, Charalampakis G, Pikazis D. Autopathogenic correlation of periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011 Jul. 50(7):1189-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barrett JH, Brennan P, Fiddler M, Silman AJ. Does rheumatoid arthritis remit during pregnancy and relapse postpartum? Results from a nationwide study in the United Kingdom performed prospectively from late pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Jun. 42(6):1219-27. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Carlens C, Hergens MP, Grunewald J, et al. Smoking, use of moist snuff, and risk of chronic inflammatory diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Jun 1. 181(11):1217-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hahn J, Malspeis S, Choi MY, Stevens E, Karlson EW, Lu B, et al. Association of Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors and the Risk of Developing Rheumatoid Arthritis among Women. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022 Jan 18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schmajuk G, Trupin L, Yelin EH, Blanc PD. Dusty trades and associated rheumatoid arthritis in a population-based study in the coal mining counties of Appalachia. Occup Environ Med. 2022 Jan 5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kerola AM, Rollefstad S, Kazemi A, Wibetoe G, Sexton J, Mars N, et al. Psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in Norway: nationwide prevalence and use of biologic agents. Scand J Rheumatol. 2022 Jan 11. 1-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jorgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Jacobsen S, Biggar RJ, Frisch M. National cohort study of reproductive risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis in Denmark: a role for hyperemesis, gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia?. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Feb. 69(2):358-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Guthrie KA, Dugowson CE, Voigt LF, Koepsell TD, Nelson JL. Does pregnancy provide vaccine-like protection against rheumatoid arthritis?. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Jul. 62(7):1842-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Shah A, St. Clair EW. Rheumatoid Arthritis. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, Eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Gremese E, Salaffi F, Bosello SL, et al. Very early rheumatoid arthritis as a predictor of remission: a multicentre real life prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jun. 72(6):858-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Cohen MD, et al. Factors associated with radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were treated with methotrexate. J Rheumatol. 2011 Feb. 38(2):242-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Agrawal S, Misra R, Aggarwal A. Autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: association with severity of disease in established RA. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Feb. 26(2):201-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vencovsky J, Machacek S, Sedova L, et al. Autoantibodies can be prognostic markers of an erosive disease in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 May. 62(5):427-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T, Hannonen P. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis 10 years after the diagnosis. J Rheumatol. 1999 Aug. 26(8):1681-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mollard E, Pedro S, Chakravarty E, Clowse M, Schumacher R, Michaud K. The impact of menopause on functional status in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 29 January 2018. [Full Text].

- Restivo V, Candiloro S, Daidone M, Norrito R, Cataldi M, Minutolo G, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular risk in rheumatological disease: Symptomatic and non-symptomatic events in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2022 Jan. 21 (1):102925. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lindhardsen J, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, et al. Risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke in rheumatoid arthritis: Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2012. 344:e1257. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Klein A, Polliack A, Gafter-Gvili A. Rheumatoid arthritis and lymphoma: Incidence, pathogenesis, biology, and outcome. Hematol Oncol. 2018 Dec. 36 (5):733-739. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bhandari B, Basyal B, Sarao MS, Nookala V, Thein Y. Prevalence of Cancer in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Epidemiological Study Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Cureus. 2020 Apr 28. 12 (4):e7870. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Parikh-Patel A, White RH, Allen M, Cress R. Risk of cancer among rheumatoid arthritis patients in California. Cancer Causes Control. 2009 Aug. 20 (6):1001-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hawley DJ. Psycho-educational interventions in the treatment of arthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1995 Nov. 9(4):803-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tucker M, Kirwan JR. Does patient education in rheumatoid arthritis have therapeutic potential?. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Jun. 50 suppl 3:422-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Thompson A. Practical aspects of therapeutic intervention in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2009 Jun. 82:39-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, Sugiyama H, Ogawa J, Saito K. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Mar 15. 61(3):305-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep. 62(9):2569-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Varache S, Narbonne V, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Is routine viral screening useful in patients with recent-onset polyarthritis of a duration of at least 6 weeks? Results from a nationwide longitudinal prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 Nov. 63(11):1565-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aletaha D, Alasti F, Smolen JS. Rheumatoid factor determines structural progression of rheumatoid arthritis dependent and independent of disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. Jul 13 2012. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Scott IC, Steer S, Lewis CM, Cope AP. Precipitating and perpetuating factors of rheumatoid arthritis immunopathology: linking the triad of genetic predisposition, environmental risk factors and autoimmunity to disease pathogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011 Aug. 25(4):447-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Daha NA, Toes RE. Rheumatoid arthritis: Are ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative RA the same disease?. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011 Apr. 7(4):202-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van Venrooij WJ, van Beers JJ, Pruijn GJ. Anti-CCP antibodies: the past, the present and the future. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011 Jun 7. 7(7):391-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mjaavatten MD, van der Heijde DM, Uhlig T, et al. Should Anti-citrullinated Protein Antibody and Rheumatoid Factor Status Be Reassessed During the First Year of Followup in Recent-Onset Arthritis? A Longitudinal Study. J Rheumatol. 2011 Nov. 38(11):2336-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bang H, Egerer K, Gauliard A, et al. Mutation and citrullination modifies vimentin to a novel autoantigen for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007. 56(8):2503–11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Coenen D, Verschueren P, Westhovens R, Bossuyt X. Technical and diagnostic performance of 6 assays for the measurement of citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies in the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chem. 2007. 53(3):498–504. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Soos L, Szekanecz Z, Szabo Z, et al. Clinical evaluation of anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin by ELISA in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007. 34(8):1658–63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bartoloni E, Alunno A, Bistoni O, Bizzaro N, Migliorini P, Morozzi G, et al. Diagnostic value of anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin in comparison to anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and anti-viral citrullinated peptide 2 antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: an Italian multicentric study and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2012 Sep. 11 (11):815-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Szekanecz Z, Soos L, Szabo Z, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: as good as it gets?. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008. 34(1):26–31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- De Winter LM, Hansen WL, van Steenbergen HW, Geusens P, Lenaerts J, Somers K, et al. Autoantibodies to two novel peptides in seronegative and early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016 Aug. 55 (8):1431-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Mar. 31 (3):315-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Radner H, Neogi T, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Performance of the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Jan. 73 (1):114-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van der Heijde DM. Radiographic imaging: the ‘gold standard’ for assessment of disease progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Jun. 39 suppl 1:9-16. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tan YK, Conaghan PG. Imaging in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011 Aug. 25(4):569-84. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McAlindon T, Kissin E, Nazarian L, Ranganath V, Prakash S, Taylor M, et al. American College of Rheumatology report on reasonable use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography in rheumatology clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Nov. 64 (11):1625-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Di Matteo A, Mankia K, Azukizawa M, Wakefield RJ. The Role of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in the Rheumatoid Arthritis Continuum. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020 Jun 19. 22 (8):41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- do Prado AD, Staub HL, Bisi MC, da Silveira IG, Mendonça JA, Polido-Pereira J, et al. Ultrasound and its clinical use in rheumatoid arthritis: where do we stand?. Adv Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 2. 58 (1):19. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Suter LG, Fraenkel L, Braithwaite RS. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and prognosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 May. 63(5):675-88. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cyteval C. Doppler ultrasonography and dynamic magnetic resonance imaging for assessment of synovitis in the hand and wrist of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2009 Mar. 13(1):66-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fukae J, Kon Y, Henmi M, Sakamoto F, Narita A, Shimizu M. Change of synovial vascularity in a single finger joint assessed by power doppler sonography correlated with radiographic change in rheumatoid arthritis: comparative study of a novel quantitative score with a semiquantitative score. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 May. 62(5):657-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zayat AS, Conaghan PG, Sharif M, et al. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have a significant effect on detection and grading of ultrasound-detected synovitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Results from a randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Oct. 70(10):1746-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kelleher MO, McEvoy L, Yang JP, Kamel MH, Bolger C. Lateral mass screw fixation of complex spine cases: a prospective clinical study. Br J Neurosurg. 2008 Oct. 22(5):663-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cakir B, Kafer W, Reichel H, Schmidt R. [Surgery of the cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. Diagnostics and indication]. Orthopade. 2008 Nov. 37(11):1127-40; quiz 1141. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Narvaez JA, Narvaez J, Serrallonga M, et al. Cervical spine involvement in rheumatoid arthritis: correlation between neurological manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 Dec. 47(12):1814-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, et al, for the American College of Rheumatology. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology Recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012. 64:640-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Verstappen SM, Albada-Kuipers GA, Bijlsma JW, et al, for the Utrecht Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort Study Group (SRU). A good response to early DMARD treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the first year predicts remission during follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005. 64:38-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aletaha D, Funovits J, Keystone EC, Smolen JS. Disease activity early in the course of treatment predicts response to therapy after one year in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007. 56:3226-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Verschueren P, Esselens G, Westhovens R. Predictors of remission, normalized physical function, and changes in the working situation during follow-up of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: an observational study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009. 38:166-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Callhoff J, Weiss A, Zink A, Listing J. Impact of biologic therapy on functional status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis--a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013 Dec. 52(12):2127-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Bass AR, Chakravarty E, Akl EA, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for Vaccinations in Patients With Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2023 Mar. 75 (3):449-464. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 May. 64 (5):625-39. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Brooks M. FDA OKs Methotrexate Autoinjector (Otrexup). Medscape Medical News. Oct 18 2013. [Full Text].

- Glen S Hazlewood, Cheryl Barnabe, George Tomlinson, Deborah Marshall, Dan Devoe, Claire Bombardier. Methotrexate monotherapy and methotrexate combination therapy with traditional and biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: abridged Cochrane systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016. 353:[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bili A, Sartorius JA, Kirchner HL, et al. Hydroxychloroquine use and decreased risk of diabetes in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011 Apr. 17(3):115-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, et al. Association between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011 Jun 22. 305(24):2525-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lane JCE, Weaver J, Kostka K, et al; OHDSI-COVID-19 consortium. Risk of hydroxychloroquine alone and in combination with azithromycin in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a multinational, retrospective study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 Aug 21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2007. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Nov. 66 Suppl 3:iii2-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Garces S, Demengeot J, Benito-Garcia E. The immunogenicity of anti-TNF therapy in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Dec. 72(12):1947-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, et al. Risk of septic arthritis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the effect of anti-TNF therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Oct. 70(10):1810-1814. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lan JL, Chen YM, Hsieh TY, et al. Kinetics of viral loads and risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B core antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis patients undergoing anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Oct. 70(10):1719-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Askling J, van Vollenhoven RF, Granath F, et al. Cancer risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapies: does the risk change with the time since start of treatment?. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Nov. 60(11):3180-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Finzel S, Rech J, Schmidt S, et al. Repair of bone erosions in rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors is based on bone apposition at the base of the erosion. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Sep. 70(9):1587-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van Vollenhoven RF, Ernestam S, Geborek P, Petersson IF, Coster L, Waltbrand E. Addition of infliximab compared with addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (Swefot trial): 1-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8. 374(9688):459-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Visser K, van der Heijde D. Optimal dosage and route of administration of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jul. 68(7):1094-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Keystone EC, Kavanaugh A, Weinblatt ME, Patra K, Pangan AL. Clinical consequences of delayed addition of adalimumab to methotrexate therapy over 5 years in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011 May. 38(5):855-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pouw MF, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Key findings towards optimising adalimumab treatment: the concentration-effect curve. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Mar. 74(3):513-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fleischmann R, Vencovsky J, van Vollenhoven RF, Borenstein D, Box J, Coteur G. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol monotherapy every 4 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing previous disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy: the FAST4WARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun. 68(6):805-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Smolen J, Landewe RB, Mease P, Brzezicki J, Mason D, Luijtens K. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. A randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun. 68(6):797-804. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, Hsia EC, Strusberg I, Durez P. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexate-naive patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: twenty-four-week results of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of golimumab before methotrexate as first-line therapy for early-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Aug. 60(8):2272-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brown T. FDA approves intravenous golimumab (Simponi Aria) for rheumatoid arthritis. Medscape Medical News. July 18, 2013. [Full Text].

- Janssen Biotech, Inc. Simponi Aria (golimumab) for infusion receives FDA approval for treatment of moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis [press release]. July 18, 2013. [Full Text].

- Weinblatt ME, Bingham CO 3rd, Mendelsohn AM, et al. Intravenous golimumab is effective in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy with responses as early as week 2: results of the phase 3, randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled GO-FURTHER trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Mar. 72(3):381-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jun 17. 350(25):2572-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peterfy C, Emery P, Tak PP, Østergaard M, DiCarlo J, Otsa K, et al. MRI assessment of suppression of structural damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving rituximab: results from the randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind RA-SCORE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Jan. 75 (1):170-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Emery P, Gottenberg JE, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. Rituximab versus an alternative TNF inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed to respond to a single previous TNF inhibitor: SWITCH-RA, a global, observational, comparative effectiveness study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jun. 74(6):979-84. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Porter D, van Melckebeke J, Dale J, Messow CM, McConnachie A, Walker A, et al. Tumour necrosis factor inhibition versus rituximab for patients with rheumatoid arthritis who require biological treatment (ORBIT): an open-label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority, trial. Lancet. 2016 Jul 16. 388 (10041):239-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bingham CO 3rd, Looney RJ, Deodhar A, Halsey N, Greenwald M, Codding C. Immunization responses in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with rituximab: results from a controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Jan. 62(1):64-74. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bedaiwi MK, Almaghlouth I, Omair MA. Effectiveness and adverse effects of anakinra in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021 Dec. 25 (24):7833-7839. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Orencia (abatacept) [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2011. Available at [Full Text].

- Genovese MC, Schiff M, Luggen M, et al. Longterm safety and efficacy of abatacept through 5 years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. J Rheumatol. Aug 2012. 39(8):1546-54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, et al. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: Findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan. 65(1):28-38. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dougados M, Kissel K, Sheeran T, et al. Adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in methotrexate inadequate responders: 24-week symptomatic and structural results of a 2-year randomised controlled strategy trial in rheumatoid arthritis (ACT-RAY). Ann Rheum Dis. Jul 7 2012. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Strand V, Burmester GR, Ogale S, Devenport J, John A, Emery P. Improvements in health-related quality of life after treatment with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomized controlled RADIATE study. Rheumatology (Oxford). Jun 28 2012. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Burmester GR, Rubbert-Roth A, Cantagrel A, et al. A randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study of the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous tocilizumab versus intravenous tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (SUMMACTA study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Jan. 73(1):69-74. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Smolen JS, Schoels MM, Nishimoto N, et al. Consensus statement on blocking the effects of interleukin-6 and in particular by interleukin-6 receptor inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Apr. 72(4):482-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Kivitz AJ, Rell-Bakalarska M, Martincova R, Fiore S, et al. Sarilumab Plus Methotrexate in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis and Inadequate Response to Methotrexate: Results of a Phase III Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Jun. 67 (6):1424-37. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Fleischmann R, van Adelsberg J, Lin Y, Castelar-Pinheiro GD, Brzezicki J, Hrycaj P, et al. Sarilumab and Nonbiologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis and Inadequate Response or Intolerance to Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Feb. 69 (2):277-290. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Fleischmann R. Novel small-molecular therapeutics for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012 May. 24(3):335-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- FDA approves Xeljanz for rheumatoid arthritis [press release]. November 6, 2012. Available at https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm327152.htm. Accessed: November 28, 2012.

- van der Heijde D, Tanaka Y, Fleischmann R, et al; ORAL Scan Investigators. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: twelve-month data from a twenty-four-month phase III randomized radiographic study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Mar. 65(3):559-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. Aug 9 2012. 367(6):495-507. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. Aug 9 2012. 367(6):508-19. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, Koch GG, Fleischmann R, Rivas JL, et al. Cardiovascular and Cancer Risk with Tofacitinib in Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jan 27. 386 (4):316-326. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brown T. FDA Approves Baricitinib for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Medscape Medical News. 2018 Jun 01. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/897516.

- Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Chen YC, Greenwald M, Drescher E, Liu J, et al. Baricitinib in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic DMARDs: results from the RA-BUILD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jan. 76 (1):88-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Chen YC, Greenwald M, Drescher E, Klar R, et al. Effects of baricitinib on radiographic progression of structural joint damage at 1 year in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. RMD Open. 2018. 4 (1):e000662. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Smolen JS, Kremer JM, Gaich CL, DeLozier AM, Schlichting DE, Xie L, et al. Patient-reported outcomes from a randomised phase III study of baricitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to biological agents (RA-BEACON). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Apr. 76 (4):694-700. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Smolen JS, Pangan AL, Emery P, Rigby W, Tanaka Y, Vargas JI, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate (SELECT-MONOTHERAPY): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019 Jun 8. 393 (10188):2303-2311. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fleischmann RM, Genovese MC, Enejosa JV, Mysler E, Bessette L, Peterfy C, et al. Safety and effectiveness of upadacitinib or adalimumab plus methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis over 48 weeks with switch to alternate therapy in patients with insufficient response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Jul 30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Tosh JC, Wailoo AJ, Scott DL, Deighton CM. Cost-effectiveness of combination nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011 Aug. 38(8):1593-600. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 30. 343(22):1594-602. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rigby W, Ferraccioli G, Greenwald M, et al. Effect of rituximab on physical function and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis previously untreated with methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011 May. 63(5):711-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- O'Dell JR, Haire CE, Erikson N, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate alone, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of all three medications. N Engl J Med. 1996 May 16. 334(20):1287-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Emery P, Horton S, Dumitru RB, Naraghi K, van der Heijde D, Wakefield RJ, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of very early etanercept and MTX versus MTX with delayed etanercept in RA: the VEDERA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jan 29. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Jones SK. Ocular toxicity and hydroxychloroquine: guidelines for screening. Br J Dermatol. 1999 Jan. 140(1):3-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006 May 17. 295(19):2275-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sohl S, Renner R, Winter U, et al. [Drug-induced lupus erythematosus tumidus during treatment with adalimumab]. Hautarzt. 2009 Oct. 60(10):826-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Soto MJ, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA. Autoimmune diseases induced by TNF-targeted therapies. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Oct. 22(5):847-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lunt M, Watson KD, Dixon WG, Symmons DP, Hyrich KL. No evidence of association between anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Nov. 62(11):3145-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Thompson AE, Rieder SW, Pope JE. Tumor necrosis factor therapy and the risk of serious infection and malignancy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Jun. 63(6):1479-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mariette X, Matucci-Cerinic M, Pavelka K, et al. Malignancies associated with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in registries and prospective observational studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Nov. 70(11):1895-904. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoes JN, Jacobs JW, Buttgereit F, Bijlsma JW. Current view of glucocorticoid co-therapy with DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010 Dec. 6(12):693-702. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buttgereit F, Doering G, Schaeffler A, et al. Efficacy of modified-release versus standard prednisone to reduce duration of morning stiffness of the joints in rheumatoid arthritis (CAPRA-1): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Jan 19 2008. 371(9608):205-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buttgereit F, Doering G, Schaeffler A, et al. Targeting pathophysiological rhythms: prednisone chronotherapy shows sustained efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. Jul 2010. 69(7):1275-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Buttgereit F, Mehta D, Kirwan J, et al. Low-dose prednisone chronotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial (CAPRA-2). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Feb. 72(2):204-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EM, et al. Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Jan. 73(1):75-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. The influence of rheumatoid arthritis disease characteristics on heart failure. J Rheumatol. 2011 Aug. 38(8):1601-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, et al, for the Cross Trial Safety Assessment Group. Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: the cross trial safety analysis. Circulation. 2008 Apr 22. 117(16):2104-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Weinblatt ME, Kavanaugh A, Genovese MC, Musser TK, Grossbard EB, Magilavy DB. An oral spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Sep. 363(14):1303-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Weinblatt ME, Genovese MC, Ho M, Hollis S, Rosiak-Jedrychowicz K, Kavanaugh A, et al. Effects of fostamatinib, an oral spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate: results from a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec. 66 (12):3255-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ince-Askan H, Dolhain RJ. Pregnancy and rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015 Aug-Dec. 29 (4-5):580-96. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ostensen M, Forger F, Nelson JL, Schuhmacher A, Hebisch G, Villiger PM. Pregnancy in patients with rheumatic disease: anti-inflammatory cytokines increase in pregnancy and decrease post partum. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Jun. 64(6):839-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Makol A, Wright K, Amin S. Rheumatoid arthritis and pregnancy: safety considerations in pharmacological management. Drugs. 2011 Oct 22. 71(15):1973-87. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Parke A, West B. Hydroxychloroquine in pregnant patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1996 Oct. 23(10):1715-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Temprano KK, Bandlamudi R, Moore TL. Antirheumatic drugs in pregnancy and lactation. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Oct. 35(2):112-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Singh JA, Saag KG, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. https://read.qxmd.com/doi/10.1002/art.39480 (2015). Arthritis Care and Research. 2015. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Androulakis I, Zavos C, Christopoulos P, Mastorakos G, Gazouli M. Safety of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Dec 21. 21 (47):13205-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bröms G, Granath F, Ekbom A, Hellgren K, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT, et al. Low Risk of Birth Defects for Infants Whose Mothers Are Treated With Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Agents During Pregnancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Feb. 14 (2):234-41.e1-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Luqmani R, Hennell S, Estrach C, et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of rheumatoid arthritis (after the first 2 years). Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Apr. 48(4):436-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Goksel Karatepe A, Gunaydin R, Turkmen G, Kaya T. Effects of home-based exercise program on the functional status and the quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: 1-year follow-up study. Rheumatol Int. 2011 Feb. 31(2):171-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Okuizumi H, Mutoh Y, Ohta M, Handa S. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise and balneotherapy: a summary of systematic reviews based on randomized controlled trials of water immersion therapies. J Epidemiol. 2010. 20(1):2-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Katz P, Margaretten M, Gregorich S, Trupin L. Physical Activity to Reduce Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017 Apr 5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lemmey AB, Marcora SM, Chester K, Wilson S, Casanova F, Maddison PJ. Effects of high-intensity resistance training in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Dec 15. 61(12):1726-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- O'Brien ET. Surgical principles and planning for the rheumatoid hand and wrist. Clin Plast Surg. 1996 Jul. 23(3):407-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Macedo AM, Oakley SP, Panayi GS, Kirkham BW. Functional and work outcomes improve in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who receive targeted, comprehensive occupational therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Nov 15. 61(11):1522-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Williams SB, Brand CA, Hill KD, Hunt SB, Moran H. Feasibility and outcomes of a home-based exercise program on improving balance and gait stability in women with lower-limb osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Jan. 91(1):106-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Siddique S, Imran Y, Afzal MN, Malik U. Effect of Ramadan fasting on disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis presenting in tertiary care hospital. Pak J Med Sci. 2020 Jul-Aug. 36 (5):1032-1035. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ben Nessib D, Maatallah K, Ferjani H, Kaffel D, Hamdi W. Impact of Ramadan diurnal intermittent fasting on rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Aug. 39 (8):2433-2440. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ben Nessib D, Maatallah K, Ferjani H, Triki W, Kaffel D, Hamdi W. Sustainable positive effects of Ramadan intermittent fasting in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2022 Feb. 41 (2):399-403. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Sriya K M Ranatunga, MD, MPH, FACP, FACR Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Chief, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

Sriya K M Ranatunga, MD, MPH, FACP, FACR is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians, American College of Rheumatology, American Medical Women's Association, Association of American Medical Colleges, Chicago Rheumatism Society, Illinois State Medical Society, Southern Illinois Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Herbert S Diamond, MD Visiting Professor of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center; Chairman Emeritus, Department of Internal Medicine, Western Pennsylvania Hospital

Herbert S Diamond, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Physicians, American College of Rheumatology, American Medical Association, Phi Beta Kappa

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Howard R Smith, MD Former Director of the Lupus Clinic, Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases, Cleveland Clinic

Howard R Smith, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Rheumatology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Edward Bessman, MD Chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, John Hopkins Bayview Medical Center; Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Edward Bessman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Sarjoo M Bhagia, MD Consulting Staff, OrthoCarolina; Voluntary Teaching Faculty, Carolinas Rehabilitation

Sarjoo M Bhagia, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Association of Academic Physiatrists, North American Spine Society, and Physiatric Association of Spine, Sports and Occupational Rehabilitation

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Heather Lyn Carone, MD Attending Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, St Vincent Mercy Medical Center

Heather Lyn Carone, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Gino A Farina, MD, FACEP, FAAEM Associate Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine; Program Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, Long Island Jewish Medical Center

Gino A Farina, MD, FACEP, FAAEM is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Patrick M Foye, MD Associate Professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Co-Director of Musculoskeletal Fellowship, Co-Director of Back Pain Clinic, Director of Coccyx Pain Service (Tailbone Pain Service: www.TailboneDoctor.com), University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, New Jersey Medical School

Patrick M Foye, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, Association of Academic Physiatrists, and International Spine Intervention Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Harris Gellman, MD Consulting Surgeon, Broward Hand Center; Voluntary Clinical Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and Plastic Surgery, Departments of Orthopedic Surgery and Surgery, University of Miami, Leonard M Miller School of Medicine

Harris Gellman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Medical Acupuncture, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Orthopaedic Association, American Society for Surgery of the Hand, and Arkansas Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Elliot Goldberg, MD Dean of the Western Pennsylvania Clinical Campus, Professor, Department of Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine

Elliot Goldberg, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American College of Physicians, and American College of Rheumatology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Kavita Gupta, DO, MEng Department of Orthopedics, Center of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Dentistry and Medicine of New Jersey

Kavita Gupta, DO, MEng is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, American Osteopathic Association, Association of Academic Physiatrists, and Pennsylvania Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

John A Kare, MD Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science/UCLA, Director of Research, Department of Emergency Medicine, Martin Luther King Jr/Charles R Drew Medical Center

John A Kare, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American Medical Student Association/Foundation, and Emergency Medicine Residents Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Randall W King, MD, FACEP Assistant Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine, The University of Toledo College of Medicine; Director, Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Associate Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, St Vincent Mercy Medical Center

Randall W King, MD, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, American Medical Association, Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, Ohio State Medical Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Challenger corporation None Physician Advisory Board; Ohio ACEP Consulting fee Editor Rivers review text Emergency Medicine

Milton J Klein, DO, MBA Consulting Physiatrist, Heritage Valley Health System-Sewickley Hospital and Ohio Valley General Hospital

Milton J Klein, DO, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Disability Evaluating Physicians, American Academy of Medical Acupuncture, American Academy of Osteopathy, American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, American Medical Association, American Osteopathic Association, American Osteopathic College of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, American Pain Society, and Pennsylvania Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Kristine M Lohr, MD, MS Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Center for the Advancement of Women's Health and Division of Rheumatology, Director, Rheumatology Training Program, University of Kentucky College of Medicine

Kristine M Lohr, MD, MS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians and American College of Rheumatology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Robert J Nowinski, DO Clinical Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, Ohio State University College of Medicine and Public Health, Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine; Private Practice, Orthopedic and Neurological Consultants, Inc, Columbus, Ohio

Robert J Nowinski, DO is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American College of Osteopathic Surgeons, American Medical Association, American Osteopathic Association, Ohio Osteopathic Association, and Ohio State Medical Association

Disclosure: Tornier Grant/research funds Other; Tornier Honoraria Speaking and teaching

Robert E O'Connor, MD, MPH Professor and Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Virginia Health System

Robert E O'Connor, MD, MPH is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physician Executives, American Heart Association, American Medical Association, Medical Society of Delaware, National Association of EMS Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, and Wilderness Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Elizabeth Salt, ARPN, PhD Assistant Professor, Division of Rheumatology, University of Kentucky College of Nursing; Rheumatology Nurse Practitioner, University of Kentucky Chandler Medical Center

Elizabeth Scarbrough, MSN is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Rheumatology, Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science, and Sigma Theta Tau International

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Roberto Sandoval, MD Consulting Staff, Department of Emergency Medicine, Anaheim Memorial Medical Center, La Palma Intercommunity Hospital

Roberto Sandoval, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians and American Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Joseph E Sheppard, MD Professor of Clinical Orthopedic Surgery, Chief of Hand and Upper Extremity Service, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Arizona Health Sciences Center, University Physicians Healthcare

Joseph E Sheppard, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Society for Surgery of the Hand, and Orthopaedics Overseas