Amyloidosis: Definition of Amyloid and Amyloidosis, Classification Systems, Systemic Amyloidoses (original) (raw)

Definition of Amyloid and Amyloidosis

Amyloid fibrils are protein polymers comprising identical monomer units (homopolymers). Functional amyloids play a beneficial role in a variety of physiologic processes (eg, long-term memory formation, gradual release of stored peptide hormones). Amyloidosis results from the accumulation of pathogenic amyloids—most of which are aggregates of misfolded proteins—in a variety of tissues. [1]

Amyloid

Amyloid is defined as in vivo deposited material distinguished by the following:

- Fibrillar appearance on electron micrography

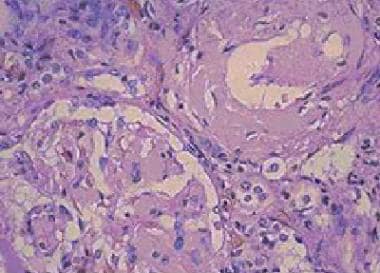

- Amorphous eosinophilic appearance on hematoxylin and eosin staining (see first image below)

- Beta-pleated sheet structure as observed by x-ray diffraction pattern

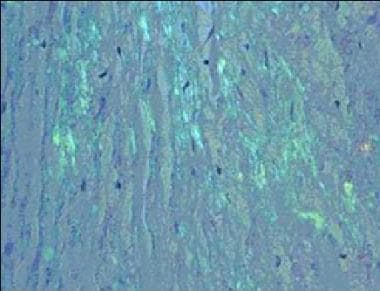

- Apple-green birefringence on Congo red histological staining (see second image below)

- Solubility in water and buffers of low ionic strength

Amyloidosis. Amorphous eosinophilic interstitial amyloid observed on a renal biopsy.

Amyloidosis. Congo red staining of a cardiac biopsy specimen containing amyloid, viewed under polarized light.

All types of amyloid consist of one major fibrillar protein that defines the type of amyloid. Polymorphisms that slightly vary native peptides or inflammatory processes set the stage for abnormal protein folding and amyloid fibril deposition. [2] Many classic eponymic diseases were later found to be related to a diverse array of misfolded polypeptides (amyloid) that contain the common beta-pleated sheet architecture.

Native or wild-type quaternary protein structure is usually born from a single translated protein sequence with one ordered conformation with downstream protein interactions. [3] However, amyloid fibrils can have different protofilament numbers, arrangements, and polypeptide conformations. [4] It is also important to understand that the same polypeptide sequence can produce many different patterns of interresidue or intraresidue interactions. [3]

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is a clinical disorder caused by extracellular and/or intracellular deposition of insoluble abnormal amyloid fibrils that alter the normal function of tissues. [5] Only 10% of amyloidosis deposits consist of components such as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), apolipoprotein-E (apoE), and serum amyloid P-component (SAP), while nearly 90% of the deposits consist of amyloid fibrils that are formed by the aggregation of misfolded proteins. These proteins either arise from proteins expressed by cells at the deposition site (localized), or they precipitate systemically after production at a local site (systemic). [6] In humans, about 23 different unrelated proteins are known to form amyloid fibrils in vivo. [7]

Many mechanisms of protein function contribute to amyloidogenesis, including “nonphysiologic proteolysis, defective or absent physiologic proteolysis, mutations involving changes in thermodynamic or kinetic properties, and pathways that are yet to be defined.” [7]

For patient education information, see Amyloidosis.

Classification Systems

Historical classification systems for amyloidosis were clinically based. Modern classification systems are biochemically based.

Historical classification systems

Until the early 1970s, the idea of a single amyloid substance predominated. Various descriptive classification systems were proposed based on the organ distribution of amyloid deposits and clinical findings. Most classification systems included primary (ie, in the sense of idiopathic) amyloidosis, in which no associated clinical condition was identified, and secondary amyloidosis, which is associated with chronic inflammatory conditions. Some classification systems included myeloma-associated, familial, and localized amyloidosis.

The modern era of amyloidosis classification began in the late 1960s with the development of methods to solubilize amyloid fibrils. These methods permitted chemical amyloid studies. Descriptive terms such as primary amyloidosis, secondary amyloidosis, and others (eg, senile amyloidosis), which are not based on etiology, provide little useful information and are no longer recommended.

Modern amyloidosis classification

Amyloid is now classified chemically. The amyloidoses are referred to with a capital A (for amyloid) followed by an abbreviation for the fibril protein. For example, in most cases formerly called primary amyloidosis and in myeloma-associated amyloidosis, the fibril protein is an immunoglobulin light chain or light chain fragment (abbreviated L); thus, patients with these amyloidoses are now said to have light chain amyloidosis (AL). Names such as AL describe the protein (light chain), but not necessarily the clinical phenotype. [6]

Similarly, in most cases previously termed senile cardiac amyloidosis and in many cases previously termed familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP), the fibrils consist of the transport protein transthyretin (TTR); these diseases are now collectively termed ATTR.

Proteins that form amyloid fibrils differ in size, function, amino acid sequence, and native structure but become insoluble aggregates that are similar in structure and properties. Protein misfolding results in the formation of fibrils that show a common beta-sheet pattern on x-ray diffraction.

In theory, misfolded amyloid proteins can be attributed to infectious sources (prions), de novo gene mutations, errors in transcription, errors in translation, errors in post-translational modification, or protein transport. For example, in ATTR, 100 different points of single mutations, double mutations, or deletions in the TTR gene and several different phenotypes of FAP have been documented. [8] Twenty-three different fibril proteins are described in human amyloidosis, with variable clinical features.

The major types of human amyloid are outlined and discussed individually in the table below. Great importance is now placed on appropriate and timely typing and classification of each type of amyloid-related disease, to focus therapy and plan appropriate monitoring. [9] The common clinical amyloid entities are AL, AA, ATTR, and Aβ2M types. [9]

Table. Human Amyloidoses (Open Table in a new window)

| Type | Fibril Protein | Main Clinical Settings |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic | Immunoglobulin light chains | Plasma cell disorders |

| Transthyretin | Familial amyloidosis, senile cardiac amyloidosis | |

| A amyloidosis | Inflammation-associated amyloidosis, familial Mediterranean fever | |

| Beta2 -microglobulin | Dialysis-associated amyloidosis | |

| Immunoglobulin heavy chains | Systemic amyloidosis | |

| Hereditary | Fibrinogen alpha chain | Familial systemic amyloidosis |

| Apolipoprotein AI | Familial systemic amyloidosis | |

| Apolipoprotein AII | Familial systemic amyloidosis | |

| Lysozyme | Familial systemic amyloidosis | |

| Central nervous system | Beta protein precursor | Alzheimer syndrome, Down syndrome, hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (Dutch) |

| Prion protein | Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease, fatal familial insomnia, kuru | |

| Cystatin C | Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (Icelandic) | |

| ABri precursor protein | Familial dementia (British) | |

| ADan precursor protein | Familial dementia (Danish) | |

| Ocular | Gelsolin | Familial amyloidosis (Finnish) |

| Lactoferrin | Familial corneal amyloidosis | |

| Keratoepithelin | Familial corneal dystrophies | |

| Localized | Calcitonin | Medullary thyroid carcinoma |

| Amylin* | Insulinoma, type 2 diabetes | |

| Atrial natriuretic factor amyloidosis | Isolated atrial amyloidosis | |

| Prolactin | Pituitary amyloid | |

| Keratin | Cutaneous amyloidosis | |

| Medin | Aortic amyloidosis in elderly people | |

| *Islet amyloid polypeptide amyloidosis. |

Systemic Amyloidoses

A amyloidosis (AA)

The precursor protein is a normal-sequence apo-SAA (serum amyloid A protein) now called "A", which is an acute phase reactant produced mainly in the liver in response to multiple cytokines. [6] "A" protein circulates in the serum bound to high-density lipoprotein.

AA occurs in various chronic inflammatory disorders, chronic local or systemic microbial infections, and occasionally with neoplasms; it was formerly termed secondary amyloidosis.. Worldwide, AA is the most common systemic amyloidosis, although the frequency has been shown to vary significantly in different ethnic groups. [10] Typical organs involved include the kidney, liver, and spleen. Some of the conditions associated with AA include the following:

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [11]

- Alzheimer disease [12]

- Multiple myeloma [13]

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis [14]

- Ankylosing spondylitis [15]

- Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [16]

- Still disease [17]

- Behçet syndrome [18]

- Familial Mediterranean fever [19]

- Crohn disease [20]

- Leprosy [21]

- Osteomyelitis [22]

- Tuberculosis [23]

- Chronic bronchiectasis [24]

- Castleman disease [25]

- Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma [26]

- Renal cell carcinoma [27]

- Gastrointestinal, lung, or urogenital carcinoma [28]

- Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) [29]

Therapy has traditionally been aimed at the underlying inflammatory condition to reduce the production of the precursor amyloid protein, SAA. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as colchicine, a microtubule inhibitor and weak immunosuppressant, can prevent secondary renal failure due to amyloid deposition specifically in familial Mediterranean fever.

Newer therapies have become more targeted to avoid the cytotoxicity of older agents (eg, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide). The SAA amyloid seen in CAPS was reduced with a biologic interleukin (IL)–1β trap called rilonacept.

Tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) is also thought to be involved in amyloid deposition. [30] Aggressive use of newer biologic therapies for RA, such as etanercept (a TNF-alpha blocker), and tocilizumab [31] have been used to decrease the concentration of SAA, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, and proteinuria in renal AA associated with RA. [32] One study compared etanercept with tocilizumab and showed that IL-6 inhibition may be a more effective therapy. [33]

Additionally, SAA isoforms have been studied using high-resolution 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis and peptide mapping by reverse-phase chromatography, electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry, and genetic analysis down to the post-translational modification level. [34] SAA is coded by 4 genes: SAA1, AAA2, SAA3, and SAA4. The SAA1 gene contributes to most of the deposits and contains a single nucleotide polymorphism that defines at least 3 haplotypes. The saa1.3 allele was found to be a risk factor and a poor prognostic indicator in Japanese RA patients. Genetic analysis has proved useful in selecting patients for biologic therapy and for predicting outcome. [35] Early treatment is essential to prevent the long-term sequelae of AA. [36]

Light chain amyloidosis (AL)

The precursor protein is a clonal immunoglobulin light chain or light chain fragment. AL is a monoclonal plasma cell disorder closely related to multiple myeloma, as some patients fulfill diagnostic criteria for multiple myeloma. Typical organs involved include the heart, kidney, peripheral nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, and nearly any other organ. AL includes former designations of primary amyloidosis and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.

Treatment usually mirrors the management of multiple myeloma (ie, chemotherapy). Selected patients have received benefit from high-dose melphalan and autologous stem-cell transplantation, with reports of prolonged survival in some studies.

The most current guidelines recommend high-dose steroids for isolated organ involvement, but transplantation should be considered early. [37] Any transplantation should also be followed by high-dose intravenous melphalan supported with stem-cell transplantation to try to prevent future amyloid deposition in the transplanted organ. [37]

Other agents used in AL amyloidosis have included bortezomib, rituximab, immunomodulatory agents, and standard-dose alkylating agents (eg, melphalan, cyclophosphamide), thalidomide, and lenalidomide. [38, 39, 37, 40] Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor that is well tolerated in multiple myeloma. [41, 42] Patients younger than 65 years may be candidates for stem cell transplantation with melphalan and dexamethasone or thalidomide-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone regimens. [37]

The response is then classified as either partial, complete, or no response. If a partial or complete response is achieved, patients are closely monitored. [37] Imaging and some biomarkers like N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), troponin, and free light-chain concentration can be useful in gauging clinical response, especially in cardiac amyloid disease. [40] If no response is seen, the patient becomes a candidate for novel agents that usually include alkylating agents combined with novel agents such as lenalidomide. [37, 43]

For more information, see Immunoglobulin-Related Amyloidosis.

Heavy chain amyloidosis (AH)

In a few cases, immunoglobulin chain amyloidosis fibrils contain only heavy-chain sequences rather than light-chain sequences, and the disease is termed AH rather than AL. Electron microscopy may be helpful in the detection of small deposits and in the differentiation of amyloid from other types of renal fibrillar deposits. [44]

For more information, see Immunoglobulin-Related Amyloidosis.

Transthyretin amyloidosis

The precursor protein is the normal- or mutant-sequence transport protein transthyretin (TTR), a transport protein synthesized in the liver and choroid plexus. TTR is a tetramer of 4 identical subunits of 127 amino acids each. Normal-sequence TTR forms amyloid deposits in the cardiac ventricles of elderly people (ie, >70 y); this disease was also termed senile cardiac amyloidosis. The prevalence of TTR cardiac amyloidosis increases progressively with age, affecting 25% or more of the population older than 90 years. Normal-sequence TTR amyloidosis (ATTR) can be an incidental autopsy finding, or it can cause clinical symptoms (eg, heart failure, arrhythmias). [45]

Point mutations in TTR increase the tendency of TTR to form amyloid. Amyloidogenic TTR mutations are inherited as an autosomal dominant disease with variable penetrance. More than 100 amyloidogenic TTR mutations are known, but many remain unknown. [46] The most prevalent TTR mutations are TTR Val30Met (common in Portugal, Japan, and Sweden), and TTR Val122Ile (carried by 3.9% of African Americans).

Amyloidogenic TTR mutations cause deposits primarily in the peripheral nerves, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and vitreous. The presentation of ATTR is fairly nonspecific, but signs and symptoms typical of chronic heart failure, polyneuropathy, and carpal tunnel syndrome occur commonly.45 Autonomic nerves are often affected before motor nerves. [47]

Treatment for mutant-sequence amyloidogenic ATTR is liver transplantation or supportive care. Liver transplantation should be performed in Val30Met patients as early as possible as it removes the main source of mutant TTR and dramatically reduces the progression of neuropathy (up to 70%) and can double the median survival. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several pharmacologic treatments for ATTR, including tafamidis for cardiomyopathy caused by ATTR and patisiran, inotersen, and vurtirsiran for polyneuropathy associated with hTTR. Additionally, revusiran, and tolcapone have demonstrated some benefit. For normal-sequence amyloidogenic ATTR_,_ the treatment is supportive care.

For details, see Transthyretin-Related Amyloidosis.

Beta2-microglobulin amyloidosis ( Abeta2M)

The precursor protein is a normal beta2 -microglobulin (β2 M), which is the light-chain component of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). In the clinical setting, β2 M is associated with patients on dialysis and, rarely, patients with renal failure who are not on dialysis.

β2 M is normally catabolized in the kidney after it is displaced from the MHC-I heavy chain in the proximal tubules, but in patients with decreased clearance the serum level of the β2 M can be more than 60 times the normal level. [48] In patients with renal failure, the protein accumulates in the serum, leading to secondary osteoarticular destruction and dialysis-related amyloidosis (DRA). [49] Aβ2 M commonly is associated with deposits in the carpal ligaments, synovium, and bone, resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome, destructive arthropathy, bone cysts, and fractures. Other organs involved include the heart, gastrointestinal tract, liver, lungs, prostate, adrenals, and tongue.

Conventional dialysis membranes do not remove β2 M, but new techniques are now being used to improve hemodialysis β2 M removal. Traut et al reported that patients using polyamide high-flux membranes had lower β2 M concentrations compared with those patients on low-flux dialyzers. [50] They postulated that the difference was mediated by an increase in β2 M mRNA, lower concentrations of β2 M released from the blood cells, and or better β2 M clearance in patients treated with high-flux dialyzers. [50] Yamamoto et al have investigated Lixelle adsorbent columns that remove serum β2 M safely in dialysis patients and significantly improved quality of life, strength, C-reactive protein levels, and β2 M concentration. [51]

Treatment also includes renal transplantation, which may arrest amyloid progression. For details, see Dialysis-Related Beta-2m Amyloidosis.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS)-associated amyloidosis

Types of CAPS include the following:

- Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS)

- Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS)

- Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID)

These disorders are typically associated with heterozygous mutations in the NLRP3 (CIAS1) gene, which encodes the cryopyrin (NALP3) protein, and are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. [52] The inflammation in CAPS is driven by excessive release of interleukin (IL)–1β. [53] IL-1β release is normally regulated by an intracellular protein complex known as the inflammasome that maps to a gene sequence called NLRP3. Mutations in NLRP3 may cause an aberrant cryopyrin protein inside the inflammasome, leading to the release of too much IL-1β and subsequent multisystem inflammation.

Secondary to increased IL-1β, CAPS patients have chronically elevated levels of acute-phase reactants, especially serum amyloid A (SAA) and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). [54, 55, 56] With elevated SAA coupled with multisystem cytokine dysregulation, multisystem amyloid deposition can be severe, with the most feared complication being renal failure. By blocking the action of IL-1β or down-regulating its production, inflammation and therefore amyloid deposition can be reduced. [57]

In a randomized double-blind CAPS therapy trial, the soluble decoy receptor rilonacept was shown to provide rapid and profound symptom improvement, in addition to improvement in measures of inflammation such as hsCRP and SAA levels. [57] In the second part of the study, continued treatment with rilonacept maintained improvements, where disease activity worsened with discontinuation of the drug. [57]

Canakinumab is a competing human immunoglobulin G (IgG) monoclonal antibody that also targets IL-1β and has shown efficacy in autoinflammatory conditions that, if untreated, are fatal by age 20 years in about 20% of individuals. [29] Both agents have the potential to cause infections, but they are usually mild and treatable.

MWS

MWS is another autoinflammatory syndrome secondary to a mutation in the CIAS gene encoding cryopyrin, a component of the inflammasome that regulates the processing of IL-1β. Patients commonly experience sensorineural hearing loss and other neuropathies. [58] The IL-1β receptor antagonist anakinra has been shown to improve the signs and symptoms in MWS by decreasing serum (hsCRP and SAA) and cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-1β. In some cases, it improved sensory deafness, as well as the laboratory values for markers of inflammation MWS. [59]

Hereditary Renal Amyloidoses

Hereditary amyloidoses encompass a group of conditions that each are related to mutations in a specific protein. The most common form is transthyretin amyloidosis (usually neuropathic), but non-neuropathic amyloidoses are likely the result of abnormalities in lysozyme, fibrinogen, alpha-chain, or apolipoprotein A-I and A-II. [60] Consider these diseases when a renal biopsy demonstrates amyloid deposition and when they are likely diagnoses (rather than light chain amyloidosis [AL] or A amyloidosis [AA]) because the family history suggests an autosomal dominant disease. Again, the definitive diagnosis is made using immunohistologic staining of the biopsy material with antibodies specific for the candidate amyloid precursor proteins. Clinical correlation is required to diagnose amyloid types, even if a hereditary form is detected by amyloid protein typing. [61]

For details, see Familial Renal Amyloidosis.

Apolipoprotein AI amyloidosis (apoAI) is an autosomal dominant amyloidosis caused by point mutations in the apoAI gene. Usually, this amyloidosis is a prominent renal amyloid but can also form in many locations. ApoAI (likely of normal sequence) is the fibril precursor in localized amyloid plaques in the aortae of elderly people. ApoAI can present either as a nonhereditary form with wild-type protein deposits in atherosclerotic plaques or as a hereditary form due to germline mutations in the apoA1 gene. [62] Currently, more than 50 apoAI variants are known and 13 are associated with amyloidosis. [62] As more gene locations are found, the clinical phenotypes are slowly being elucidated.

Fibrinogen amyloidosis (AFib) is an autosomal dominant amyloidosis caused by point mutations in the fibrinogen alpha chain gene. If DNA sequences indicate a mutant amyloid precursor protein, protein analysis of the deposits must provide the definitive evidence in laboratories with sophisticated methods. [61]

Lysozyme amyloidosis (ALys) is an autosomal dominant amyloidosis caused by point mutations in the lysozyme gene.

Apolipoprotein AII amyloidosis (AapoAII) is an autosomal dominant amyloidosis caused by point mutations in the apoAII gene. The 2 kindreds described with this disorder have each carried a point mutation in the stop codon, leading to production of an abnormally long protein.

Central Nervous System Amyloidoses and Other Localized Amyloidoses

Central nervous system amyloidoses

Beta protein amyloid

The amyloid beta precursor protein (AβPP), which is a transmembrane glycoprotein, is the precursor protein in beta protein amyloid (A). Three distinct clinical settings are as follows:

- Alzheimer disease has a normal-sequence protein, except in some cases of familial Alzheimer disease, in which mutant beta protein is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

- Down syndrome has a normal-sequence protein that forms amyloids in most patients by the fifth decade of life.

- Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (HCHWA), Dutch type, is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The beta protein contains a point mutation. These patients typically present with cerebral hemorrhage followed by dementia.

The accumulation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) in the brain both in the form of plaques in the cerebral cortex and in blood vessel as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) causes progressive cognitive decline. Researchers have used immunization strategies to neutralize amyloid fibrils before deposition. Experimental models and human clinical trials have shown that accumulation of Aβ plaques can be reversed by immunotherapy. Aβ immunization results in solubilization of plaque Aβ42 which, at least in part, exits the brain via the perivascular pathway, causing a transient increase in the severity of CAA. The extent to which these vascular alterations following Aβ immunization in Alzheimer disease are reflected in changes in cognitive function remains to be determined. [63]

Newer research has focused on finding a way to prevent the parent molecules from fragmenting and then aggregating to form toxic oligomers. Aβ peptide is known as a factor in the pathology of Alzheimer disease. Aβ aggregation is dependent on monomer concentration, nucleus formation, fibril elongation, and fibril fragmentation. Cellular, kinetic, and radiolabeling experiments have demonstrated that secondary nucleation occurs on the surface of only specific types of Aβ fibrils. The work focused on Aβ42, which could be a target molecule for future therapies to prevent nucleation events, oligomer formation rates, and neurotoxic effects. [64]

Other target fibrils with secondary amyloidogenic nucleation potential are also being investigated across large-scale comparative data sets. [65]

Prion protein amyloidosis (APrP)

The precursor protein in APrP is a prion protein, which is a plasma membrane glycoprotein. The etiology is either infectious (ie, kuru) and transmissible spongiform encephalitis (TSE) or genetic (ie, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [CJD], Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker [GSS] syndrome, fatal familial insomnia [FFI]). The infectious prion protein is a homologous protein encoded by a host chromosomal gene, which induces a conformational change in a native protease-sensitive protein, increasing the content of beta-pleated sheets. The accumulation of these beta-pleated sheets renders the protein protease-resistant and therefore amyloidogenic. [66] Patients with TSE, CJD, GSS, and FFI carry autosomal dominant amyloidogenic mutations in the prion protein gene; therefore, the amyloidosis forms even in the absence of an infectious trigger.

Similar infectious animal disorders include scrapie in sheep and goats and bovine spongiform encephalitis (ie, mad cow disease).

Cystatin C amyloidosis

The precursor protein in cystatin C amyloidosis (ACys) is cystatin C, which is a cysteine protease inhibitor that contains a point mutation. This condition is clinically termed HCHWA, Icelandic type.

ACys is autosomal dominant. Clinical presentation includes multiple strokes and mental status changes beginning in the second or third decade of life. Many of the patients die by age 40 years. This disease is documented in a 7-generation pedigree in northwest Iceland. The pathogenesis is one of mutant cystatin that is widely distributed in tissues, but fibrils form only in the cerebral vessels; therefore, local conditions must play a role in fibril formation.

Non-amyloid beta cerebral amyloidosis (chromosome 13 dementias)

Two syndromes (British and Danish familial dementia) that share many aspects of clinical Alzheimer disease have been identified. Findings include the presence of neurofibrillary tangles, parenchymal preamyloid and amyloid deposits, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and amyloid-associated proteins. Both conditions have been linked to specific mutations on chromosome 13; they cause abnormally long protein products (ABri and ADan) that ultimately result in different amyloid fibrils.

Other localized amyloidoses

Gelsolin amyloidosis

This disorders was first reported in 1969 and found to be heritable in a Finnish family in an autosomal dominant fashion. A flurry of research uncovered the molecular dysfunction of the disease but a treatment approach has yet to be devised. Gelsolin amyloidosis has now been described in countries all over the world and is often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. [67]

Amyloid fibrils include a gelsolin fragment that contains a point mutation. Two amyloidogenic gelsolin mutations are described. "A G654A or G654T DNA mutation in the gelsolin coding area (q32–34) of chromosome 9, which changes an aspartate at position 187 in the gelsolin protein to an asparagine or tyrosine (D187N/Y) residue respectively. These mutations lead to gelsolin fragment formation and amyloidogenesis." [67] .

The precursor protein in gelsolin amyloidosis (AGel) is the ubiquitous actin-modulating protein gelsolin, but the mutated form lacks a crucial calcium binding site, allowing it to unfold and expose the amino acid chain to proteolysis while processed in the Golgi and again after exocytosis, forming an 8- and 5-kd amyloidogenic fragment. [68, 69] When the gelsolin gene is transcribed, some is spliced to form cytoplasm and some is secreted from the cell, but only the secreted forms deposit as amyloid secondary to faulty post-translational modification of gelsolin. [70] Mass spectrometric-based proteomic analysis and immunohistochemical staining can reliably differentiate amyloid as gelsolin type. [71, 72, 73]

Most early symptoms are ocular; thus, the ophthalmologist is crucial in early diagnosis. Clinical characteristics include slowly progressive cranial neuropathies, distal peripheral neuropathy, and lattice corneal dystrophy. Gelsolin gene sequencing is the only confirmatory test, but tissue samples can also be stained with tagged, commercially available gelsolin antibodies to provide a solid pathology diagnosis. [74] An extremely detailed review of this condition, along with the recent scientific developments, was published by Solomon et al in 2012. [67]

Atrial natriuretic factor amyloidosis

The precursor protein is atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), a hormone controlling salt and water homeostasis that is synthesized by the cardiac atria. Amyloid deposits are localized to the cardiac atria. This condition is highly prevalent in elderly people and generally is of little clinical significance. ANF amyloidosis (AANF) is most common in patients with long-standing congestive heart failure, presumably because of persistent ANF production. Proper diagnosis requires extensive testing, including paraffin blocks of tissue for molecular typing by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and observation of Congo red staining on affected atrial tissues. [75] No known relation exists to the amyloidoses that involve the cardiac ventricles (ie, AL, ATTR).

Keratoepithelin amyloidosis and lactoferrin amyloidosis

Point mutations occur in a gene termed BIGH3, which encodes keratoepithelin and leads to autosomal dominant corneal dystrophies characterized by the accumulation of corneal amyloid. Some BIGH3 mutations cause amyloid deposits, and others cause nonfibrillar corneal deposits. Another protein, lactoferrin, is also reported as the major fibril protein in familial subepithelial corneal amyloidosis. The relationship between keratoepithelin and lactoferrin in familial corneal amyloidosis is not yet clear.

Calcitonin amyloid

In calcitonin amyloid (ACal), the precursor protein is calcitonin, a calcium regulatory hormone synthesized by the thyroid. Patients with medullary carcinoma of the thyroid may develop localized amyloid deposition in the tumors, consisting of normal-sequence procalcitonin (ACal). The presumed pathogenesis is increased local calcitonin production, leading to a sufficiently high local concentration of the peptide and causing polymerization and fibril formation.

Islet amyloid polypeptide amyloidosis

In islet amyloid polypeptide amyloidosis (AIAPP), the precursor protein is an islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), also known as amylin. IAPP is a protein secreted by the islet beta cells that are stored with insulin in the secretory granules and released in concert with insulin. Normally, IAPP modulates insulin activity in skeletal muscle, influencing energy homeostasis, satiety, blood glucose levels, adiposity, and even body weight. [76] IAPP amyloid is found in insulinomas and in the pancreas of many patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2). IAPP could be toxic at the competitive or non-competitive level. IAPP analogs are now being investigated in the treatment of DM2 and obesity. [76]

Prolactin amyloid

In prolactin amyloid (Apro), prolactin or prolactin fragments are found in the pituitary amyloid. This condition is often observed in elderly people and has also been reported in an amyloidoma in a patient with a prolactin-producing pituitary tumor. The spherical amyloid deposits have a characteristic MRI appearance that differs from common pituitary adenomas. [77]

Keratin amyloid

Some forms of cutaneous amyloid react with antikeratin antibodies. The identity of the fibrils is not chemically confirmed in keratin amyloid (Aker). Aker is often described as primary cutaneous amyloidosis and is extremely rare. [78]

Medin amyloid

Aortic medial amyloid occurs in most people older than 60 years. Medin amyloid (AMed) is derived from a proteolytic fragment of lactadherin, a glycoprotein expressed by mammary epithelium.

Nonfibrillar Components of Amyloid

All types of amyloid deposits contain not only the major fibrillar component (solubility in water, buffers of low ionic strength), but also nonfibrillar components that are soluble in conventional ionic-strength buffers. The role of the minor components in amyloid deposition is not clear. These components do not appear to be absolutely required for fibril formation, but they may enhance fibril formation or stabilize formed fibrils.

The nonfibrillar components, contained in all types of amyloid, are discussed below. However, note that other components found in some types of amyloid include complement components, proteases, and membrane constituents.

Pentagonal component

Pentagonal (P) component comprises approximately 5% of the total protein in amyloid deposits. This component is derived from the circulating serum amyloid P (SAP) component, which behaves as an acute-phase reactant. The P component is one of the pentraxin group of proteins, with homology to C-reactive protein. In experimental animals, amyloid deposition is slowed without the P component.

Radiolabeled material homes to amyloid deposits; therefore, this component can be used in amyloid scans to localize and quantify amyloidosis and to monitor therapy response. Radiolabeled P component scanning has proven clinically useful in England, where the technology was developed, but it is available in only a few centers worldwide.

Apolipoprotein E

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) is found in all types of amyloid deposits.

One allele, ApoE4, increases the risk for beta protein deposition, which is associated with Alzheimer disease. ApoE4 as a risk factor for other forms of amyloidosis is controversial.

The role of apoE in amyloid formation is not known.

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)

GAGs are heteropolysaccharides composed of long, unbranched polysaccharides that contain a repeating disaccharide unit. These proteoglycans are basement membrane components intimately associated with all types of tissue amyloid deposits. Amyloidotic organs contain increased amounts of GAGs, which may be tightly bound to amyloid fibrils. Heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate are the GAGs most often associated with amyloidosis.

Heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate have an unknown role in amyloidogenesis. Studies of A amyloidosis (AA) and light chain amyloidosis (AL) amyloid have shown marked restriction of the heterogeneity of the glycosaminoglycan chains, suggesting that particular subclasses of heparan and dermatan sulfates are involved.

Compounds that bind to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (eg, anionic sulfonates) decrease fibril deposition in murine models of AA and have been suggested as potential therapeutic agents.

Mechanisms of Amyloid Formation

Amyloid protein structures

In all forms of amyloidosis, the cell secretes the precursor protein in a soluble form that becomes insoluble at some tissue site, compromising organ function. All the amyloid precursor proteins are relatively small (ie, molecular weights 4000-25,000) and do not share any amino acid sequence homology. The secondary protein structures of most soluble precursor proteins (except for SAA and chromosomal prion protein [Prpc]) have substantial beta-pleated sheet structure, while extensive beta-sheet structure occurs in all of the deposited fibrils.

In some cases, hereditary abnormalities (primarily point mutations or polymorphisms) in the precursor proteins are present (eg, lysozyme, fibrinogen, cystatin C, gelsolin). In other cases, fibrils form from normal-sequence molecules (eg, AL, β2 M). In other cases, normal-sequence proteins can form amyloid, but mutations underlying inflammatory milieu accelerate the process (eg, TTR, beta protein precursor or CAPS).

Deposition location

In localized amyloidoses, the deposits form close to the precursor synthesis site; however, in systemic amyloidoses, the deposits may form either locally or at a distance from the precursor-producing cells. Amyloid deposits primarily are extracellular, but reports exist of fibrillar structures within macrophages and plasma cells.

Proteolysis and protein fragments

In some types of amyloidosis (eg, always in AA, often in AL and ATTR), the amyloid precursors undergo proteolysis, which may enhance folding into an amyloidogenic structural intermediate. In addition, some of the amyloidoses may have a normal proteolytic process that is disturbed, yielding a high concentration of an amyloidogenic intermediate. For example, it was shown that the mast cells of allergic responses may also participate in the development of secondary or amyloid AA in chronic inflammatory conditions. Mast cells hasten the partial degradation of the SAA protein that can produce highly amyloidogenic N-terminal fragments of SAA. However, factors that lead to different organ tropisms for the different amyloidoses are still largely unknown.

Whether the proteolysis occurs before or after tissue deposition is unclear in patients in whom beta protein fragments are observed in tissue deposits. In some types of amyloid (eg, AL, Aβ, ATTR), nonfibrillar forms of the same molecules can accumulate before fibril formation; thus, nonfibrillar deposits, in some cases, may represent intermediate deposition.

Approach to Diagnosing Amyloidosis

Pathologic diagnosis (Congo red staining and immunohistochemistry)

Immunocytochemical studies for amyloid should include the following [79] :

- Stains for Congo red (apple-green birefringence)

- Hematoxylin and eosin stains for amorphous material

- Kappa and lambda light chains

- Beta-amyloid A4 protein,

- Transthyretin

- Beta 2-microglobulin

- Cystatin C

- Gelsolin

- Immunoreactivity with antiamyloid AA antibody

Amyloidosis is diagnosed when Congo red–binding material is demonstrated in a biopsy specimen. Because different types of amyloidosis require different approaches to treatment, determining only that a patient has a diagnosis of amyloidosis is no longer adequate. A clinical situation may suggest the type of amyloidosis, but the diagnosis generally must be confirmed by immunostaining a biopsy specimen. Antibodies against the major amyloid fibril precursors are commercially available. For example, AL, ATTR, and Aβ2 M can present as carpal tunnel syndrome or gastrointestinal amyloidosis, but each has a different etiology and requires a different treatment approach.

Similarly, determining whether the amyloid is of the AL or ATTR type is often difficult in patients with cardiac amyloidosis, because the clinical picture usually is similar. Without immunostaining to identify the type of deposited protein, an incorrect diagnosis can lead to ineffective and, perhaps, harmful treatment. Be wary of drawing diagnostic conclusions from indirect tests (eg, monoclonal serum proteins) because the results of these presumptive diagnostic tests can be misleading; for example, monoclonal serum immunoglobulins are common in patients older than 70 years, but the most common form of cardiac amyloidosis is derived from TTR.

New adjuncts to traditional laboratory testing are now available. The serum free light chain test is commercially available and can aid in screening, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment monitoring by detecting low concentrations of free light chains and can measure the ratio of kappa chains to lambda chains. [80]

Diagnosis by subcutaneous fat aspiration

For many years, rectal biopsy was the first procedure of choice. An important clinical advance was the recognition that the capillaries in the subcutaneous fat are often involved in patients with systemic amyloidosis and can often provide sufficient tissue for the diagnosis of amyloid, immunostaining, and, in some cases, amino acid sequence analysis; thus, biopsy of the organ with the most severe clinical involvement is often unnecessary.

For example, in cardiac amyloidosis, the definitive diagnosis of the type of amyloid can be made using an endomyocardial biopsy specimen, with Congo red and immunologic staining of the tissue sample. Alternatively, when noninvasive testing suggests cardiac amyloidosis, studying a subcutaneous fat aspiration instead of endomyocardial biopsy, thereby avoiding an invasive procedure, often provides a specific diagnosis.

Organ biopsies

It is important to recognize that not all biopsy sites offer the same sensitivity. The best sites from which to obtain a biopsy specimen in systemic amyloidosis are the abdominal fat pad and rectal mucosa (approaching 90% sensitivity for fat pad and 73-84% for rectal mucosa). [81] While some imaging modalities can strongly suggest amyloidosis, a tissue sample showing birefringent material is still the criterion standard. This is definitely the case in terms of cardiac specific amyloid. While, endomyocardial biopsy is the best confirmatory test for local cardiac amyloid deposition, it can be very risk averse and requires a center of excellence with the full complement of immunohistochemical and molecular-based testing. [82]

When the subcutaneous fat aspiration biopsy (the least invasive biopsy site) does not provide information to reach a firm diagnosis, biopsy specimens can be obtained from other organs. In addition, an advantage to performing a biopsy of an involved organ (eg, kidney, heart) is that it definitively establishes a cause-and-effect relationship between the organ dysfunction and amyloid deposition.

Other sites that are often sampled but have poor sensitivity for the diagnosis of amyloid include the salivary glands, skin, tongue, gingiva, stomach, and bone marrow. A recent study suggests that the duodenum may be the most sensitive biopsy site compared with the gingiva, esophagus, or gastric antrum in AA renal disease. [83]

Imaging

Several modalities can help visualize amyloid deposits. Cardiac amyloidosis can be visualized with gated MRI and technetium pyrophosphate (99m Tc-PYP) scintography. [84] In some cases, scintography can distinguish AL from ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. [85]

Imaging techniques such as structural MRI and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) can show structure and function pathology longitudinally, but "the extent and topographical distribution of Aβ deposition correlates relatively poorly with cognitive profile, severity or progression of the clinical deficit." [86]

Amyloid Arthropathy

Articular and periarticular consequences of amyloidosis often mimic rheumatoid arthritis (RA), polymyalgia rheumatica, autoinflammatory syndromes, seronegative spondyloarthritis, and plasma cell dyscrasias. [87] Whether causal or just associated, various autoimmune diseases can also predispose to the deposition of amyloid fibrils. Amyloid deposition in inflammatory syndromes is amplified by the underlying inflammatory state, significantly increasing morbidity and mortality, especially in the case of renal amyloidosis. [88] However, autopsy study shows that amyloid arthropathy in RA is often undiagnosed in patients with long-standing severe RA. [89]

Amyloid arthropathy is classically seen in the shoulders, knees, wrists, and elbows, and this may be explained by that fact that these are sites that are commonly aspirated. Amyloid arthropathy can mimic classic RA but usually lacks the intense distal synovitis and can affect the hips, knees, and shoulders more than peripheral joints. [90]

Synovial fluid may contain amyloid fibrils, although it is not particularly inflammatory, with white blood cell counts on average less than 2000 cells/µL. Synovial biopsies reveal marked synovial villi hypertrophy. The classic “shoulder-pad” sign denotes end-stage amyloid deposits in the shoulder synovium and periarticular structures, but is rarely seen.

Another articular structure commonly affected by amyloid deposition is the carpal tunnel. Carpal tunnel syndrome can be the presenting sign of primary or secondary forms of amyloid, as only minimal deposits are required to impair nerve conduction. The diagnosis can be made with biopsy at the time of carpal tunnel release surgery or other joint procedures. It can be helpful to obtain pathology even on routine carpal tunnel release surgeries, as this is a great opportunity for a tissue diagnosis. In a pathology review of 124 patients undergoing carpal tunnel release without a previous diagnosis or clinical signs of amyloidosis, 82% had amyloid deposition. At 10-year follow-up, only 2 patients had systemic amyloidosis diagnosed after amyloid was discovered in their tenosynovium. [91]

Radiography may reveal irregularly shaped hyperlucencies, subchondral cysts, and erosions that will correspond with low-intensity signals on both T1 and T2 MRIs. [92] Ultrasound investigations may also show lucencies, soft-tissue changes, power Doppler changes, increased thickness of tendons, and joint effusions with echogenic zones.

Up to 5% of patients with long-standing RA can develop systemic amyloidosis that usually presents as nephrotic syndrome. [90] Genetic study can predict certain haplotypes that can increase the risk of developing amyloidosis by 7 times. [88] The hope is that this increase in the understanding of haplotypes and proteomics will lead to more specific therapies.

Interestingly, with the advent of more effective therapies for inflammatory arthritis, the incidence of amyloidosis secondary to RA has decreased from 5% to less than 1%. [90]

Incidence of Amyloidosis

The incidence of amyloid associated with long-standing inflammatory disease may be decreasing with improved treatment to target strategies and focused biologic therapeutics. The overall incidence of various types of amyloidosis has declined over the last 10 years, and the decline can be directly linked to wider information sharing, prompt treatment of underlying disease, and increased used of disease-modifying therapy and targeted biological therapy. [93]

In Finland, the overall number of patients requiring renal replacement therapy in the setting of amyloidosis has decreased over 50% in 10 years, while the use of methotrexate has increased almost 4-fold. [94] This was the first study to prove this drop in amyloid-related kidney disease, but the results were contrary to an earlier study that only showed the average age of amyloid-related renal disease was rising. [94] Investigational bias, however, may be confounding the incidence data, with a 2013 study showing the incidence renal amyloidosis may be rising. [95]

However, certain subsets of renal amyloid are decreasing, such as the HIV-related renal amyloid, which now only accounts for a fraction of HIV-related kidney disease in the setting of widespread highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). [96]

Treatment of Amyloidosis

Patisiran

Patisiran (Onpattro) was the first drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in August 2018, for treatment of polyneuropathy caused by hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR) in adults. The first of a new class of targeted RNA-based therapies, patisiran acts by using RNA to interfere with the production of mutant transthyretin (TTR) protein, thereby reducing serum TTR protein levels and TTR protein deposits in tissues. It is administered by intravenous (IV) infusion every 3 weeks.

Approval was based on the APOLLO clinical trial, in which patients taking patisiran (n=148) showed significantly improved scores on the Neuropathy Impairment Score+7 and Norfolk Quality of Life Questionnaire–Diabetic Neuropathy (QOL-DN) at 18 months, compared with those taking placebo (n=77) (P < 0.001). [97]

Inotersen

Inotersen (Tegsedi) was approved by the FDA in October 2018. Like patisiran, it is indicated for polyneuropathy of hATTR in adults; unlike patisiran, inotersen is given as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection that the patient or caregiver can administer. It is an antisense oligonucleotide that causes degradation of mutant and wild-type transthyretin mRNA by binding TTR mRNA. This action results in reduced TTR protein levels in serum and tissue.

Approval was based on a placebo-controlled trial in which patients (n=172) were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive weekly inotersen or placebo. Scores on the mNIS+7 and the QOL-DN showed improvement in those receiving inotersen (P < 0.001). [98]

Vutrisiran

Vutrisiran (Amvuttra) gained FDA approval in June 2022 for polyneuropathy of hATTR in adults. Like patisiran, it is an siRNA that affects TTR. It is administered subcutaneously every 3 months. Approval was based on results from HELIOS-A, a global, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 study in which164 patients with hATTR amyloidosis were randomized 3:1 to receive either vutrisiran or patisiran for 18 months. The efficacy of vutrisiran was also assessed by comparing the vutrisiran group in HELIOS-A with the placebo group (n = 77) from the APOLLO phase 3 study of patisiran.

Vutrisiran met the primary endpoint of the study, the change from baseline in the modified Neuropathy Impairment Score + 7 (mNIS+7) at 9 months. Treatment with vutrisiran (N = 114) resulted in a 2.2 point mean decrease (improvement) in mNIS+7 from baseline compared with a 14.8 point mean increase (worsening) reported for the external placebo group (N = 67), resulting in a 17.0 point mean difference relative to placebo (p < 0.0001). By 9 months, 50% of patients treated with vutrisiran experienced improvement in neuropathy impairment relative to baseline.

Vutrisiran also met all secondary endpoints with significant improvement in the Norfolk Quality of Life Questionnaire-Diabetic Neuropathy (Norfolk QoL-DN) score and timed 10-meter walk test (10-MWT), and improvements were observed in exploratory endpoints, including change from baseline in modified body mass index (mBMI), all relative to external placebo. Efficacy results at 18 months were consistent with 9-month data. [99, 100, 101]

Tafamidis

Transthyretin amyloidosis is related to abnormal conformational changes and transthyretin aggregation, leading to severe neuropathy and cardiomyopathy. After learning the structure and function of transthyretin, researchers developed a molecule and later a drug, tafamidis, that could stabilize the native tetrameric state of transthyretin. [102]

The FDA approved tafamidis meglumine (Vyndaqel) and tafamidis (Vyndamax) for cardiomyopathy caused by transthyretin mediated amyloidosis (ATTR-CM) in adults in 2019. These are the first FDA-approved treatments for ATTR-CM. Although the two products have the same active moiety, tafamidis, they are not substitutable on a milligram-to milligram basis and their recommended doses differ.

Efficacy of tafamidis was shown in a randomized clinical trial in which all-cause mortality and rates of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations were lower in the 264 patients who received tafamidis than in the 177 patients who received placebo (P < 0.001). After an average of 30 months, patients receiving tafamidis also had a lower rate of decline in distance for the 6-minute walk test (P < 0.001) and a lower rate of decline in KCCQ-OS score (P < 0.001). [103]

A phase II, open-label, single-treatment arm evaluated the pharmacodynamics, efficacy, and safety of tafamidis in patients with non-Val30Met transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis. Twenty-one patients with 8 different non-Val30Met mutations received daily oral tafamidis, and many experienced improved quality of life measures, while pro-BNP and echocardiographic features improved. [104] Another study showed that long-term use continued to stabilize TTR at 30 months. In a cross-over scheme, patients previously given placebo showed slowing in their neurologic decline, proving that earlier treatment is better. [105] Clinical trials for use in amyloidosis polyneuropathy are ongoing.

Doxycycline

A pilot study demonstrated reduction in arthralgia and increased range of motion with doxycycline treatment. The authors theorize that doxycycline inhibits β2-microglobulin fibrillogenesis and inhibits the accumulation in bone architecture. Their trial monitored long-term dialysis patients with severe amyloid arthropathy. Use of a low dose of 100 mg of doxycycline daily provided pain reduction, increased range of motion, and no adverse effects at 5 months. [106]

Beta-2m–adsorbing columns for dialysis

β2-m–adsorbing columns have demonstrated some benefit in dialysis-related amyloidosis. This addition to long-term dialysis may reduce inflammation and accumulation of fibrils without major adverse effects. [107]

Immunotherapy

Amyloid betA (Aβ) immunotherapies have shown some promise in the treatment of Alzheimer disease. The anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies aducanumab and lecanemab have received FDA approval for this indication. Other agents in this class, such as bapineuzumab, [51] solanezumab, [108] ponezumab, [109] crenezumab, [110] and gantenerumab [111] have failed to provide meaningful cognitive changes in clinical trials. [112] In a phase II trial, ponezumab also failed to show efficacy in the treatment of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. [113]

Tocilizumab

A subset of patients with amyloidosis (AA) in the setting of arthritis were monitored for benefits from the IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab. After a year of therapy with the standard regimen for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (8 mg/kg q4wk) a significant reduction in kidney dysfunction, serum AA concentration, and urinary protein secretion was observed in conjunction with reduced disease activity. These patients had been previously treated with etanercept without these benefits. [31] This study again highlights the importance of treating the underlying condition, but certain biologic targets may have more downstream effects on amyloidogenesis.

Daratumumab/hyaluronidase

The FDA granted accelerated approval to daratumumab/hyaluronidase (Darzalex Faspro) in combination with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone for newly diagnosed light chain (AL) amyloidosis in 2021. Approval was based on the open-label, active-controlled ANDROMEDA trial, in which patients (n=388) with newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis were randomized to receive bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VCd arm) or with Darzalex Faspro (D-VCd arm). The hematologic complete response rate was 42.1% for the D-VCd arm and 13.5% for the VCd arm. [114]

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines prefer clinical trial participation but also recommend daratumumab/hyaluronidase, in combination with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) as a category 1, preferred primary therapy option for patients with systemic light chain amyloidosis. [115] A joint guideline from the European Society of Haematology and the International Society of Amyloidosis regarding non-transplant chemotherapy treatment for patients with AL amyloidosis also recommend consideration of clinical trial participation, but otherwise recommend daratumumab/CyBorD for most untreated patients. [116]

Bortezomib

In AL amyloidosis, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has proved effective, especially as pretreatment before high-dose melphalan followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that the addition of bortezomib to treatment of AL amyloidosis resulted in significantly improved overall response rate (ORR), complete response, cardiac response rate, and 2-year overall survival; risk of neuropathy and overall mortality were both reduced. [117]

Other medications

Other innovative medicines have been developed to block hepatic production of both mutant and wild type TTR (noxious in late-onset forms of NAH after age 50 y), and to remove amyloid deposits (monoclonal anti-SAP). [118] Clinical trials should first include patients with late-onset FAP or non-met30 TTR familial amyloid polyneuropathy who are less responsive to LT7 and patients in whom tafamidis is ineffective or inappropriate. Initial and periodic cardiac assessment is necessary, as cardiac impairment is inevitable and largely responsible for mortality. Symptomatic treatment is crucial to improve these patients' quality of life.

Transplantation

Autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) has been used in patients with AL amyloidosis. Initially, high rates of early mortality raised concern about the safety of ASCT in this setting, but a study of Mayo Clinic patients found that treatment-related mortality declined from 14.5% in 1996-2002 to 2.4% in 2010-2016 (P < 0.001). Median overall survival for those periods increased from 75 months to not reached. Hematologic response rates rose from 69% to 84%. The authors conclude that ASCT is likely to remain an important first-line treatment, even when novel agents become available.

Treatment Response in Amyloidosis

While amyloidosis is a very heterogeneous disease, there has been a focused effort to define what a meaningful response to therapy looks like. Each affected organ can be measured over time.

In cardiac amyloidosis, the prognosis was historically thought to carry a poor prognosis. However, recent advances in diagnosis, which permit early recognition, and new treatment for various forms of amyloidosis that can affect the heart, permit improved survival and good quality of life for many of these patients. [119]

Improvement in cardiac amyloidosis is defined as a 2-mm decrease in mean interventricular septal thickness, 20% improvement in ejection fraction, improvement by 2 New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes without an increase in diuretic use, and no increase in wall thickness, and/or a reduction (≥30% and ≥300 ng/L) of N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) in patients in whom the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m2. [120]

For kidney-related amyloidosis, use of interleukin-1 inhibitors, interleukin-6 inhibitors, and tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors to reduce serum amyloid A protein formation has significantly improved the prognosis of this entity. [121] A meaningful clinical response in these patients is defined as "50% decrease (at least 0.5 g/day) of 24-hr urine protein (urine protein must be > 0.5 g/day pre-treatment) in the absence of a reduction in eGFR ≥25% or an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.5 mg/dL". [120]

For liver-related amyloid, a decrease in the size of the liver by 2 cm radiographically and a 50% drop in the alkaline phosphatase level is a meaningful clinical response goal. [120]

Supportive Care

Symptomatic care in amyloidosis is paramount, given the limited targeted therapeutics. Certain organ-specific types of amyloid are beginning to have standards of supportive care.

For example, cardiac amyloidosis requires judicious use of rate and rhythm control agents to prevent fatal arrhythmias. Amyloid can infiltrate the conduction system and the coronary arteries. [122] Clues to aid in early detection are the presence of cardiac arrhythmia with early heart failure evidenced by abnormal echocardiogram. [123]

Considerations regarding drug therapy include the following:

- Certain medications such as digoxin or calcium channel blockers are dangerous to the already-hindered conduction system in cardiac amyloid.

- Higher doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors can also foster dangerous hypotension and are not recommended. [120]

- Beta-blockers are relatively contraindicated in cardiac amyloidosis and are associated with a higher death rate. [124]

- Amiodarone (200 mg PO q5d/wk) prevents arrhythmias and should be considered first and continued indefinitely. [125]

Very gentle afterload reduction with diuretics is important to decrease the effects of restrictive pathology and higher filling pressures, but orthostasis is common and dangerous. Attempting to make peripheral edema resolve with diuretics is not advised and can cause dangerously low cardiac output. If the patient has low and labile blood pressure that is thought to be related to autonomic dysfunction, midodrine, an alpha agonist, may improve blood pressure. [124]

Defibrillators may be a life-saving option for fatal arrhythmias, but there are no strong data indicating they prevent mortality. [126] Even so, pacemakers may still have a role in preventing symptomatic bradycardia or conduction blocks. [127]

Questions & Answers

- Chuang E, Hori AM, Hesketh CD, Shorter J. Amyloid assembly and disassembly. J Cell Sci. 2018 Apr 13. 131 (8):86-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006. 75:333-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fandrich M, Meinhardt J, Grigorieff N. Structural polymorphism of Alzheimer Abeta and other amyloid fibrils. Prion. 2009 Apr-Jun. 3(2):89-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Fandrich M. On the structural definition of amyloid fibrils and other polypeptide aggregates. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007 Aug. 64(16):2066-78. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bustamante JG, Zaidi SRH. Amyloidosis. 2023 Jan. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Westermark P, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Cohen AS, Frangione B, Ikeda S, et al. A primer of amyloid nomenclature. Amyloid. 2007 Sep. 14(3):179-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buxbaum JN. The systemic amyloidoses. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004 Jan. 16(1):67-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ando Y, Ueda M. Novel methods for detecting amyloidogenic proteins in transthyretin related amyloidosis. Front Biosci. 2008. 13:5548-58. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hazenberg BP. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013 May. 39(2):323-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Buck FS, Koss MN, Sherrod AE, Wu A, Takahashi M. Ethnic distribution of amyloidosis: an autopsy study. Mod Pathol. 1989 Jul. 2(4):372-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shin JK, Jung YH, Bae MN, Baek IW, Kim KJ, Cho CS. Successful treatment of protein-losing enteropathy due to AA amyloidosis with octreotide in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2013 Mar. 23(2):406-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tam JH, Pasternak SH. Amyloid and Alzheimer's disease: inside and out. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012 May. 39(3):286-98. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Basha HI, Raj E, Bachuwa G. Cardiac amyloidosis masquerading as biventricular hypertrophy in a patient with multiple myeloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Jul 29. 2013:[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saha A, Chopra Y, Theis JD, Vrana JA, Sethi S. AA amyloidosis associated with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013 Oct. 62(4):834-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cammelli D. [Extra-articular manifestations of seronegative spondylarthritis]. Recenti Prog Med. 2006 May. 97(5):280-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bergis M, Dega H, Planquois V, Benichou O, Dubertret L. [Amyloidosis complicating psoriatic arthritis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Nov. 130(11):1039-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kishida D, Okuda Y, Onishi M, Takebayashi M, Matoba K, Jouyama K. Successful tocilizumab treatment in a patient with adult-onset Still's disease complicated by chronic active hepatitis B and amyloid A amyloidosis. Mod Rheumatol. 2011 Apr. 21(2):215-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Erten S, Perçinel S, Olmez U, Ensari A, Düzgün N. Behçet's disease associated with diarrhea and secondary amyloidosis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb. 22(1):106-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lane T, Loeffler JM, Rowczenio DM, Gilbertson JA, Bybee A, Russell TL. AA amyloidosis complicating the hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Apr. 65(4):1116-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Denis MA, Cosyns JP, Persu A, Dewit O, de Galocsy C, Hoang P. Control of AA amyloidosis complicating Crohn's disease: a clinico-pathological study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013 Mar. 43(3):292-301. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Silva Júnior GB, Barbosa OA, Barros Rde M, Carvalho Pdos R, Mendoza TR, Barreto DM. [Amyloidosis and end-stage renal disease associated with leprosy]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010 Jul-Aug. 43(4):474-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Neugebauer C, Graf R. [Expert opinion problems in the evaluation of osteomyelitis]. Orthopade. 2004 May. 33(5):603-11; quiz 612. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lekpa FK, Ndongo S, Pouye A, Tiendrebeogo JW, Ndao AC, Ka MM. [Amyloidosis in sub-Saharan Africa]. Med Sante Trop. 2012 Jul-Sep. 22(3):275-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Akçay S, Akman B, Ozdemir H, Eyüboglu FO, Karacan O, Ozdemir N. Bronchiectasis-related amyloidosis as a cause of chronic renal failure. Ren Fail. 2002 Nov. 24(6):815-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Caro-Cuenca MT, Ortega-Salas R, Espinosa-Hernández M. Renal AA amyloidosis in a Castleman's disease patient. Nefrologia. 2012. 32(5):699-700. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Caro-Cuenca MT, Ortega-Salas R, Espinosa-Hernández M. Renal AA amyloidosis in a Castleman's disease patient. Blood. 2013 Jul 18. 122(3):458-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nobata H, Suga N, Itoh A, Miura N, Kitagawa W, Morita H, et al. Systemic AA amyloidosis in a patient with lung metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. Amyloid. 2012 Dec. 19(4):197-200. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rivera R, Kaul V, DeCross A, Whitney-Miller C. Primary gastric amyloidosis presenting as an isolated gastric mass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Jul. 76(1):186-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yokota S, Kikuchi M, Nozawa T, Kizawa T, Kanetaka T, Miyamae T, et al. [An approach to the patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS) : a new biologic response modifier, canakinumab]. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 2012. 35(1):23-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Smith GR, Tymms KE, Falk M. Etanercept treatment of renal amyloidosis complicating rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med J. 2004 Sep-Oct. 34(9-10):570-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Miyagawa I, Nakayamada S, Saito K, Hanami K, Nawata M, Sawamukai N. Study on the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis complicated with AA amyloidosis. Mod Rheumatol. 2013 Oct 21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nakamura T, Higashi S, Tomoda K, Tsukano M, Baba S. Efficacy of etanercept in patients with AA amyloidosis secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007 Jul-Aug. 25(4):518-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Okuda Y, Ohnishi M, Matoba K, Jouyama K, Yamada A, Sawada N, et al. Comparison of the clinical utility of tocilizumab and anti-TNF therapy in AA amyloidosis complicating rheumatic diseases. Mod Rheumatol. 2014 Jan. 24(1):137-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ducret A, Bruun CF, Bures EJ, Marhaug G, Husby G, Aebersold R. Characterization of human serum amyloid A protein isoforms separated by two-dimensional electrophoresis by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis. 1996 May. 17(5):866-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nakamura T. Clinical strategies for amyloid A amyloidosis secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2008. 18(2):109-18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lane T, Loeffler JM, Rowczenio DM, Gilbertson JA, Bybee A, Russell TL, et al. AA amyloidosis complicating the hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Apr. 65(4):1116-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Merlini G, Seldin DC, Gertz MA. Amyloidosis: pathogenesis and new therapeutic options. J Clin Oncol. 2011 May 10. 29(14):1924-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sissoko M, Sanchorawala V, Seldin D, Sworder B, Angelino K, Broce M, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment responses in IgM-related AL amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2015. 22 (4):229-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Reece DE, Hegenbart U, Sanchorawala V, et al. Weekly and twice-weekly bortezomib in AL amyloidosis: Results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010. 28:578s.

- Wechalekar AD, Goodman HJ, Lachmann HJ, Offer M, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD. Safety and efficacy of risk-adapted cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone in systemic AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2007 Jan 15. 109(2):457-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kastritis E, Anagnostopoulos A, Roussou M, Toumanidis S, Pamboukas C, Migkou M, et al. Treatment of light chain (AL) amyloidosis with the combination of bortezomib and dexamethasone. Haematologica. 2007 Oct. 92(10):1351-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sitia R, Palladini G, Merlini G. Bortezomib in the treatment of AL amyloidosis: targeted therapy?. Haematologica. 2007 Oct. 92(10):1302-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, Hayman SR, et al. A phase II study of pomalidomide and dexamethasone in previously treated light-chain (AL) amyloidosis. J Clin Oncol. 2010. 28:579s.

- Picken MM. Immunoglobulin light and heavy chain amyloidosis AL/AH: renal pathology and differential diagnosis. Contrib Nephrol. 2007. 153:135-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Connors LH, Sam F, Skinner M, Salinaro F, Sun F, Ruberg FL, et al. Heart Failure Resulting From Age-Related Cardiac Amyloid Disease Associated With Wild-Type Transthyretin: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. Circulation. 2016 Jan 19. 133 (3):282-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Planté-Bordeneuve V. [The diagnosis and management of familial amyloid polyneuropathy]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2006 Nov. 162(11):1138-46. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gonzalez-Duarte A. Autonomic involvement in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR amyloidosis). Clin Auton Res. 2018 Mar 6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Floege J, Bartsch A, Schulze M, Shaldon S, Koch KM, Smeby LC. Clearance and synthesis rates of beta 2-microglobulin in patients undergoing hemodialysis and in normal subjects. J Lab Clin Med. 1991 Aug. 118(2):153-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Otsubo S, Kimata N, Okutsu I, Oshikawa K, Ueda S, Sugimoto H, et al. Characteristics of dialysis-related amyloidosis in patients on haemodialysis therapy for more than 30 years. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 May. 24(5):1593-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Traut M, Haufe CC, Eismann U, Deppisch RM, Stein G, Wolf G. Increased binding of beta-2-microglobulin to blood cells in dialysis patients treated with high-flux dialyzers compared with low-flux membranes contributed to reduced beta-2-microglobulin concentrations. Results of a cross-over study. Blood Purif. 2007. 25(5-6):432-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schenk D. Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002 Oct. 3(10):824-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001 Nov. 29(3):301-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dinarello CA. Unraveling the NALP-3/IL-1beta inflammasome: a big lesson from a small mutation. Immunity. 2004 Mar. 20(3):243-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- van der Hilst JC, Simon A, Drenth JP. Hereditary periodic fever and reactive amyloidosis. Clin Exp Med. 2005 Oct. 5(3):87-98. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, Aganna E, McDermott MF. Spectrum of clinical features in Muckle-Wells syndrome and response to anakinra. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Feb. 50(2):607-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, Gelabert A, Jones J, Rubin BI. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 10. 355(6):581-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hoffman HM, Throne ML, Amar NJ, Sebai M, Kivitz AJ, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilonacept (interleukin-1 Trap) in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: results from two sequential placebo-controlled studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Aug. 58(8):2443-52. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Stew BT, Fishpool SJ, Owens D, Quine S. Muckle-Wells syndrome: a treatable cause of congenital sensorineural hearing loss. B-ENT. 2013. 9(2):161-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yamazaki T, Masumoto J, Agematsu K, Sawai N, Kobayashi S, Shigemura T, et al. Anakinra improves sensory deafness in a Japanese patient with Muckle-Wells syndrome, possibly by inhibiting the cryopyrin inflammasome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Mar. 58(3):864-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Granel B, Valleix S, Serratrice J, Chérin P, Texeira A, Disdier P, et al. Lysozyme amyloidosis: report of 4 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006 Jan. 85(1):66-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Picken MM, Linke RP. Nephrotic syndrome due to an amyloidogenic mutation in fibrinogen A alpha chain. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Aug. 20(8):1681-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Eriksson M, Schönland S, Yumlu S, Hegenbart U, von Hutten H, Gioeva Z, et al. Hereditary apolipoprotein AI-associated amyloidosis in surgical pathology specimens: identification of three novel mutations in the APOA1 gene. J Mol Diagn. 2009 May. 11(3):257-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, et al. Consequence of Abeta immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer's disease brain. Brain. 2008 Dec. 131:3299-310. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cohen SI, Linse S, Luheshi LM, Hellstrand E, White DA, Rajah L. Proliferation of amyloid-ß42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jun 11. 110(24):9758-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Emily M, Talvas A, Delamarche C. MetAmyl: a METa-predictor for AMYLoid proteins. PLoS One. 2013. 8(11):e79722. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Rezaei H. Prion protein oligomerization. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008 Dec. 5(6):572-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Solomon JP, Page LJ, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Gelsolin amyloidosis: genetics, biochemistry, pathology and possible strategies for therapeutic intervention. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2012 May-Jun. 47(3):282-96. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chen CD, Huff ME, Matteson J, Page L, Phillips R, Kelly JW. Furin initiates gelsolin familial amyloidosis in the Golgi through a defect in Ca(2+) stabilization. EMBO J. 2001 Nov 15. 20(22):6277-87. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chiti F, Stefani M, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM. Rationalization of the effects of mutations on peptide and protein aggregation rates. Nature. 2003 Aug 14. 424(6950):805-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kangas H, Paunio T, Kalkkinen N, Jalanko A, Peltonen L. In vitro expression analysis shows that the secretory form of gelsolin is the sole source of amyloid in gelsolin-related amyloidosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1996 Sep. 5(9):1237-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ida CM, Yan X, Jentoft ME, Kip NS, Scheithauer BW, Morris JM. Pituicytoma with gelsolin amyloid deposition. Endocr Pathol. 2013 Sep. 24(3):149-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Choe H, Burtnick LD, Mejillano M, Yin HL, Robinson RC, Choe S. The calcium activation of gelsolin: insights from the 3A structure of the G4-G6/actin complex. J Mol Biol. 2002 Dec 6. 324(4):691-702. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Huff ME, Page LJ, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Gelsolin domain 2 Ca2+ affinity determines susceptibility to furin proteolysis and familial amyloidosis of finnish type. J Mol Biol. 2003 Nov 14. 334(1):119-27. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Haverland N, Pottiez G, Wiederin J, Ciborowski P. Immunoreactivity of anti-gelsolin antibodies: implications for biomarker validation. J Transl Med. 2010 Dec 20. 8:137. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Podduturi V, Armstrong DR, Hitchcock MA, Roberts WC, Guileyardo JM. Isolated atrial amyloidosis and the importance of molecular classification. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2013 Oct. 26(4):387-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Abedini A, Schmidt AM. Mechanisms of islet amyloidosis toxicity in type 2 diabetes. FEBS Lett. 2013 Apr 17. 587(8):1119-27. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Levine SN, Ishaq S, Nanda A, Wilson JD, Gonzalez-Toledo E. Occurrence of extensive spherical amyloid deposits in a prolactin-secreting pituitary macroadenoma: a radiologic-pathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013 Aug. 17(4):361-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wenson SF, Jessup CJ, Johnson MM, Cohen LM, Mahmoodi M. Primary cutaneous amyloidosis of the external ear: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 17 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012 Feb. 39(2):263-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kebbel A, Röcken C. Immunohistochemical classification of amyloid in surgical pathology revisited. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006 Jun. 30(6):673-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rao M, Lamont JL, Chan J, Concannon TW, Comenzo R, Ratichek SJ, et al. Serum Free Light Chain Analysis for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prognosis of Plasma Cell Dyscrasias: Future Research Needs: Identification of Future Research Needs From Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 73 [Internet]. 2012 Sep. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- West S, Singleton JD. Rheumatology Secrets. 2nd ed. Philadelpha, PA: Hanley and Belfus; 2003. 519.

- Thiene G, Bruneval P, Veinot J, Leone O. Diagnostic use of the endomyocardial biopsy: a consensus statement. Virchows Arch. 2013 Jul. 463(1):1-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yilmaz M, Unsal A, Sokmen M, Harmankaya O, Alkim C, Kabukcuoglu F, et al. Duodenal biopsy for diagnosis of renal involvement in amyloidosis. Clin Nephrol. 2012 Feb. 77(2):114-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Castaño A, Bokhari S, Brannagan TH 3rd, Wynn J, Maurer MS. Technetium pyrophosphate myocardial uptake and peripheral neuropathy in a rare variant of familial transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis (Ser23Asn): a case report and literature review. Amyloid. 2012 Mar. 19(1):41-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].