Pheochromocytoma Imaging: Practice Essentials, Radiography, Computed Tomography (original) (raw)

In 1912, a pathologist named Pick coined the term pheochromocytoma —after the Greek words phaios, meaning dark or dusky, and chroma, meaning color—to describe the chromaffin reaction seen in adrenomedullary tumors. The tumors arise from the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and are associated with increased catecholamine production. Although chromaffin tissue is also present elsewhere in the body, such as in the mediastinum, along the aorta, and in the pelvis, the term pheochromocytoma is reserved for tumors that arise from the adrenal medulla. Chromaffin cell tumors at other locations are more appropriately called paragangliomas or chemodectomas, although the term extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma is still applied. [1, 2] (Examples of pheochromocytomas are shown below.)

Patients with sporadic pheochromocytoma present at a mean age of approximately 44 years, and those with a genetic predisposition present at about 25 years of age. [1] Annual incidence is reported to be 2-8 per million and prevalence 0.05–0.12%. [2]

According to the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) Endocrine and Head and Neck Disease Site Working Group, pheochromocytomas constitute about 4–8% of all adrenal incidentalomas, and approximately 21.1–57.6% of all pheochromocytomas are discovered incidentally on imaging studies. [3]

Symptomatic patients typically present in their fourth or fifth decade of life, and between 90 and 95% of the tumors are unifocal and benign. The likelihood of malignancy depends on the primary site (adrenal vs. extra-adrenal) and the presence of certain germline mutations, such as SDHB in particular. [3]

Imaging modalities

Patients who may be referred for imaging of the adrenal glands include those with new or worsening diabetes mellitus (owing to impaired glucose regulation) and those with hypertensive crisis after anesthesia, surgery, or treatment with medications. Imaging may also be performed in patients with a known history of multiple endocrine problems. [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

The Endocrine Society recommends CT as the initial imaging study, but MRI is a better option in patients with metastatic disease or when radiation exposure must be limited. [12] MRI is more specific for pheochromocytomas than CT scanning, but MRI is not tolerable for some patients.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have higher sensitivity in detecting pheochromocytomas than nuclear medicine scanning with iodine-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG), although 131I-MIBG uptake is more specific. Some authors prefer to use MIBG uptake scanning as the initial screening modality because it enables whole-body imaging, making it useful for the detection of extra-adrenal tumors and metastatic deposits. [11, 1, 13, 14, 15, 2, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

Positron emission tomography (PET) is also an alternative imaging test, with agents such as 18F-deoxyglucose (F-FDG), 18F-dihydroxyphenaline (F-DOPA), and 18F-fluorodopamine (F-FDA) being used in cases of negative 123I-MIBG when there is a high clinical and laboratory suspicion. PET with 18F-FDG has been shown to have a greater sensitivity than 123I-MIBG scintigraphy for metastatic disease because, in these cases, the tumors are generally less differentiated and therefore lose the ability to efficiently capture 123I-MIBG. [21]

Once an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor is detected, CT scanning or MRI of the region may be performed for anatomic localization prior to surgical removal. If 131I-MIBG uptake is negative but the clinical findings suggest pheochromocytoma, CT scanning or MRI of the chest or abdomen may be performed, because the false-negative rate of MIBG scintigraphy is 10%. [22, 1, 2, 17, 18, 19, 20]

Luster et al investigated the specificity and sensitivity of (18)F-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, CT scanning, and a combination of the 2 modalities in the identification and localization of adrenal and extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas. Nineteen lesions were detected by all 3 imaging methods, but only DOPA PET/CT scanning accurately characterized and localized them all, demonstrating, on a per-patient basis, a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 88%. [23]

A further study by Gaertner et al concluded the (18)F-LMI1195 is a promising tracer for tumor imaging. [24] Saad et al found in a study of 23 patients with a history of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma that (18)F-FDG PET/CT was a superior tool for the localization of recurrent tumors. [25]

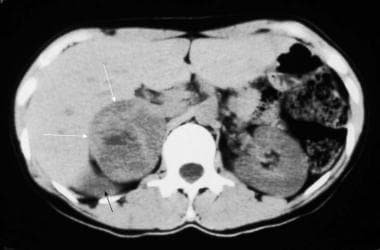

Nonenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan in a 35-year-old woman with hypertension demonstrates a large, right-sided, inhomogeneous adrenal mass (white arrows) with a central area of low attenuation that represents hemorrhage or necrosis. The upper pole of the displaced right kidney can be seen (black arrow). Courtesy of Dr Ali Shirkhoda, William Beaumont Hospital, Michigan.

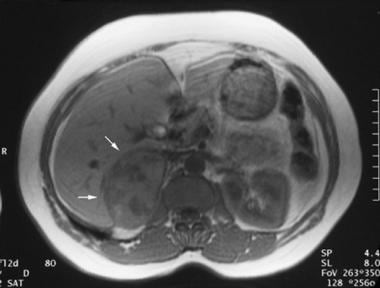

Axial gradient-recalled magnetic resonance angiogram in a 42-year-old woman with a 5-year history of hypertension who underwent magnetic resonance angiography for the assessment of renal arterial stenosis. Although the renal arteries were unremarkable, a 7.5-cm X 5-cm right adrenal mass was incidentally identified. Angiogram demonstrates a large, right-sided, inhomogeneous adrenal mass (arrows). Courtesy of Dr Ali Shirkhoda, William Beaumont Hospital, Michigan.

Detecting the tumors is important for a number of reasons. First, hypertension is usually cured with the removal of the tumor, whereas untreated patients are at risk for a lethal hypertensive paroxysm and long-term sequelae of the disease. Second, the discovery of a pheochromocytoma may indicate the presence of a familial disorder. Third, approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas are malignant. Incidentally, pheochromocytomas are called the 10% tumor because they are associated with a 10% risk of malignancy, because 10% of the tumors are bilateral, and because 10% of the tumors are extra-adrenal. Early detection may reduce the risk of metastasis.

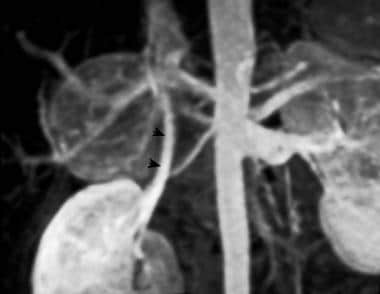

Usually, tumors are larger than 3 cm when seen. They are highly vascular (see the images below), and larger tumors are prone to hemorrhage and necrosis, even when they are benign.

Selective adrenal angiogram demonstrates the highly vascular nature of a pheochromocytoma. Courtesy of Dr Ali Shirkhoda, William Beaumont Hospital, Michigan.

Three-dimensional maximal-intensity magnetic resonance angiogram clearly demonstrates a large, hypervascular right adrenal mass. Arrowheads demarcate the right renal vein. Courtesy of Dr Ali Shirkhoda, William Beaumont Hospital, Michigan.

Failure to make the correct diagnosis can create serious risks for the patient. Early surgical removal of the adrenal gland is important to prevent complications associated with pheochromocytomas. Delay can significantly increase the risk of an adverse event. Worse, if pheochromocytoma is not considered in the diagnosis, the injection of contrast material, especially ionic contrast material, can provoke a hypertensive crisis.

Therefore, exclusion of pheochromocytoma should be part of the diagnostic evaluation in every patient with a suprarenal mass. Some authors recommend 131I-MIBG scintigraphy and/or the use of laboratory tests to confirm or rule out excessive production of catecholamines, prior to the use of invasive procedures.

Limitation of techniques

Unfortunately, the cost and lack of availability of MIBG studies restrict its use. In addition, imaging with 131I-MIBG can be time-consuming, and the technique has limited ability to provide sufficiently accurate information for surgery. Therefore, some authors recommend the use of at least 2 of the following modalities: CT scanning, MRI, and MIBG uptake studies. [1, 20]

CT scanning is quick and relatively inexpensive, and it offers good spatial localization. CT scan findings are not specific enough to distinguish masses caused by pheochromocytoma from other adrenal masses. Additionally, some authors report a risk of hypertensive crisis after the injection of contrast material.

MRI is more specific for pheochromocytomas than is CT scanning, but some patients cannot tolerate MRI.

Guidelines

The Endocrine Society recommends CT for initial imaging, but they note that MRI is a better option in patients with metastatic disease or when radiation exposure must be limited. They add that 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy is a useful imaging modality for metastatic pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas (PPGL). [12]

The SSO Endocrine and Head and Neck Disease Site Working Group notes that CT is often the first imaging performed. MRI is not as commonly used as CT, and typically, MRI shows increased signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging and, as with CT, variable patterns of postcontrast enhancement. Historically, 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) has been the primary functional imaging method, but a number of studies have consistently demonstrated the superiority of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT over other functional imaging methods. [3]

The European Society of Endocrinology suggests screening for metastatic tumors by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) and performing imaging tests every 1-2 years in patients with biochemically inactive PPGLs to screen for local or metastatic recurrences or new tumors. [26]

The European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) and Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) published the following information regarding image acquisition and interpretation [27] :

- PPGLs have different preferential sites of origin that must be known. Integration of functional and anatomic imaging in hybrid SPECT/CT or PET/CT devices is strongly recommended.

- Images are generally acquired from the top of the skull (for a large jugular PGL) to the pelvis. In cases where recurrent or metastatic disease is suspected, whole-body images are necessary.

- Metastases from PPGLs are often small and numerous and could be difficult to localize precisely on co-registered CT images obtained by combined SPECT/CT and PET/CT (plain CT, thick anatomical sections, or a positional shift between CT and nuclear images).

The following guidelines were provided by societies taking a multidisciplinary approach, including the Spanish Societies of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN), Medical Oncology (SEOM), Medical Radiology (SERAM), Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SEMNIM), Otorhinolaryngology (SEORL), Pathology (SEAP), Radiation Oncology (SEOR), and Surgery (AEC) and Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) [28] :

- The diagnosis of PPGL relies on the imaging identification of an appropriately located mass with consistent clinical and biochemical features. Once the diagnosis is clinically and biochemically confirmed, imaging studies should be performed to localize and stage the tumor.

- CT is the most common imaging method used because it is widely available and because it is less expensive and offers better spatial resolution than MRI.

- MRI is not a first-choice imaging tool, but it has the advantage of being free of ionizing radiation and is suitable for children, pregnant women, and patients with adverse reactions to iodinated contrast medium.

- PPGL cells express different transporters on their surface that allow images to be obtained by different radiotracers depending on the capture mechanisms, thus yielding different functional information. The most sensitive functional image for each tumor will depend on the clinical and biochemical profiles and the location of the primary tumor, which are also predictors of the underlying genotype.

- Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT technology has been shown to be superior to scintigraphy with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT/CT), with higher spatial resolution, greater sensitivity, and fewer indeterminate or equivocal studies.

- Generally, when facing metastatic disease, better results are reported with the use of 18F-FDG PET/CT.