Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

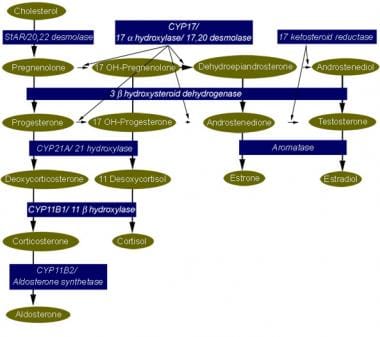

The term congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) encompasses a group of autosomal recessive disorders, each of which involves a deficiency of an enzyme involved in the synthesis of cortisol, [1, 2] aldosterone, or both. Deficiency of 21-hydroxylase, resulting from mutations or deletions of CYP21A, is the most common form of CAH, accounting for more than 90% of cases. [3] The diagnosis of CAH depends on the demonstration of inadequate production of cortisol and/or aldosterone in the presence of accumulation of excess concentrations of precursor hormones. [2] (See the image below.)

Steroidogenic pathway for cortisol, aldosterone, and sex steroid synthesis. A mutation or deletion of any of the genes that code for enzymes involved in cortisol or aldosterone synthesis results in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The particular phenotype that results depends on the sex of the individual, the location of the block in synthesis, and the severity of the genetic deletion or mutation.

Signs and symptoms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

The clinical phenotype of CAH depends on the nature and severity of the enzyme deficiency. Although the presentation varies according to chromosomal sex, the sex of a neonate with CAH is often initially unclear because of genital ambiguity.

Clinical presentation in females

- Females with severe CAH due to deficiencies of 21-hydroxylase, 11-beta-hydroxylase, or 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase have ambiguous genitalia at birth (classic virilizing adrenal hyperplasia); genital anomalies range from complete fusion of the labioscrotal folds and a phallic urethra to clitoromegaly, partial fusion of the labioscrotal folds, or both

- Females with mild 21-hydroxylase deficiency are identified later in childhood because of precocious pubic hair, clitoromegaly, or both, often accompanied by accelerated growth and skeletal maturation (simple virilizing adrenal hyperplasia)

- Females with still milder deficiencies of 21-hydroxylase or 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity may present in adolescence or adulthood with oligomenorrhea, hirsutism, and/or infertility (nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia) [4]

- Females with 17-hydroxylase deficiency appear phenotypically female at birth but do not develop breasts or menstruate in adolescence; they may present with hypertension

Clinical presentation in males

- Males with 21-hydroxylase deficiency have normal genitalia

- If the defect is severe and results in salt wasting, these male neonates present at age 1-4 weeks with failure to thrive, recurrent vomiting, dehydration, hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and shock (classic salt-wasting adrenal hyperplasia)

- Males with less severe deficiencies of 21-hydroxylase present later in childhood with early development of pubic hair, phallic enlargement, or both, accompanied by accelerated linear growth and advancement of skeletal maturation (simple virilizing adrenal hyperplasia)

- Males with steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) deficiency, classic 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency, or 17-hydroxylase deficiency generally have ambiguous genitalia or female genitalia; they may be raised as girls and seek medical attention later in life because of hypertension or a lack of breast development

Other findings

- Patients with aldosterone deficiency of any etiology may present with dehydration, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia, especially with the stress of illness

- Males or females with 11-hydroxylase deficiency may present in the second or third week of life with a salt-losing crisis; later in life, these patients develop hypertension, hypokalemic alkalosis, or both

- Infants with StAR deficiency (lipoid adrenal hyperplasia) usually have signs of adrenal insufficiency (eg, poor feeding, vomiting, dehydration, hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia)

- Hyperpigmentation: Occurs in patients with deficiencies of enzyme activity involved in cortisol synthesis; may be subtle and is best observed in the genitalia and areolae

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)

The diagnosis of CAH depends on the demonstration of inadequate production of cortisol, aldosterone, or both in the presence of accumulation of excess concentrations of precursor hormones, as follows:

- 21-hydroxylase deficiency: High serum concentration of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (usually >1000 ng/dL) and urinary pregnanetriol (metabolite of 17-hydroxyprogesterone) in the presence of clinical features suggestive of the disease; 24-hour urinary 17-ketosteroid levels are elevated

- 11-beta-hydroxylase deficiency: Excess serum concentrations of 11-deoxycortisol and deoxycorticosterone, or an elevation in the ratio of 24-hour urinary tetrahydrocompound S (metabolite of 11-deoxycortisol) to tetrahydrocompound F (metabolite of cortisol); 24-hour urinary 17-ketosteroid levels are elevated

- 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency: An abnormal ratio of 17-hydroxypregnenolone to 17-hydroxyprogesterone and of dehydroepiandrosterone to androstenedione

- Salt-wasting forms of CAH: Low serum aldosterone concentrations, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and elevated plasma renin activity (PRA), indicating hypovolemia

- Hypertensive forms of adrenal hyperplasia (ie, 11-beta-hydroxylase deficiency and 17-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency) are associated with suppressed PRA and, often, hypokalemia

- Subtle forms of adrenal hyperplasia (as in nonclassic forms of 21-hydroxylase deficiency and nonclassic 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency): Synthetic corticotropin (Cortrosyn) stimulation testing demonstrates the abnormal accumulation of precursor steroids; nomograms are available for interpreting the results [5]

Imaging studies

- CT scanning of the adrenal gland can help exclude bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in patients with signs of acute adrenal failure without ambiguous genitalia or other clues to adrenal hyperplasia [6]

- Pelvic ultrasonography may be performed in an infant with ambiguous genitalia to demonstrate a uterus or associated renal anomalies, which are sometimes found in other conditions that may result in ambiguous genitalia (eg, mixed gonadal dysgenesis, Denys-Drash syndrome)

- Urogenitography is often helpful in defining the anatomy of the internal genitalia

- A bone-age study is useful in evaluating for advanced skeletal maturation in a child who develops precocious pubic hair, clitoromegaly, or accelerated linear growth

Other tests

- A karyotype is essential in an infant with ambiguous genitalia, to establish the chromosomal sex

- Genetic testing is essential for genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis of adrenal hyperplasia

- Newborn screening programs for 21-hydroxylase deficiency may be lifesaving in an affected male infant who would otherwise be undetected until presentation with a salt-wasting crisis [7]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Newborns with ambiguous genitalia should be closely observed for symptoms and signs of salt wasting while a diagnosis is being established. Clinical clues include abnormal weight loss or lack of expected weight gain. Electrolyte abnormalities generally take from a few days to 3 weeks to appear, but in mild forms of salt-wasting adrenal hyperplasia, salt wasting may not become apparent until an illness stresses the child.

Management is as follows:

- Patients with dehydration, hyponatremia, or hyperkalemia and a possible salt-wasting form of CAH should receive an IV bolus of isotonic sodium chloride solution (20 mL/kg or 450 mL/m2) over the first hour, as needed, to restore intravascular volume and blood pressure; this may be repeated if the blood pressure remains low

- Dextrose must be administered if the patient is hypoglycemic and must be included in the rehydration fluid after the bolus dose to prevent hypoglycemia

- After samples are obtained to measure electrolyte, blood sugar, cortisol, aldosterone, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone concentrations, the patient should be treated with glucocorticoids; treatment should not be withheld while confirmatory results are awaited

- After the patient's condition is stabilized, treat all patients who have adrenal hyperplasia with long-term glucocorticoid or aldosterone replacement (or both), depending on which enzyme is involved and on whether cortisol and/or aldosterone synthesis is affected

- Patients who are sick and have signs of adrenal insufficiency should receive stress dosages of hydrocortisone (50-100 mg/m2 or 1-2 mg/kg IV administered as an initial dose), followed by 50-100 mg/m2/day IV divided every 6 hours

The Endocrine Society's 2018 clinical practice guidelines include the following [8] :

- It is advised that prenatal treatment for CAH be regarded as experimental

- The addition of fludrocortisone and sodium supplementation to the treatment regimen is recommended for newborns and patients in early infancy

- Daily hydrocortisone and/or long-acting glucocorticoids plus mineralocorticoids are recommended, as clinically indicated, for adults with classic CAH

- Behavioral/mental health consultation and evaluation are recommended for persons with CAH and for their parents, to address CAH-related concerns

Surgical care

Infants with ambiguous genitalia require surgical evaluation and, if needed, plans for corrective surgery, as follows:

- The traditional approach to the female patient with ambiguous genitalia due to adrenal hyperplasia is clitoral recession early in life followed by vaginoplasty after puberty [9]

- Vocal groups of patients with disorders of sexual differentiation (eg, Intersex Society of North America) have challenged this approach

- Some female infants with adrenal hyperplasia have only mild virilization and may not require corrective surgery if they receive adequate medical therapy to prevent further virilization

The Endocrine Society's 2018 clinical practice guidelines include the following [8] :

- It is suggested “that bilateral adrenalectomy not be performed” in patients with CAH

- It is advised that parents of all pediatric patients with CAH, especially those of minimally virilized girls, “be informed about surgical options, including delaying surgery and/or observation until the child is older”

- With regard to severely virilized females, discussion is advised concerning early surgery for urogenital sinus repair

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The term congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) encompasses a group of autosomal recessive disorders, each of which involves a deficiency of an enzyme involved in the synthesis of cortisol, [1] aldosterone, or both.

Pathophysiology

The clinical manifestations of each form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia are related to the degree of cortisol deficiency and/or the degree of aldosterone deficiency. In some cases, these manifestations reflect the accumulation of precursor adrenocortical hormones. When present in supraphysiologic concentrations, these precursors lead to excess androgen production with resultant virilization, or because of mineralocorticoid properties, cause sodium retention and hypertension.

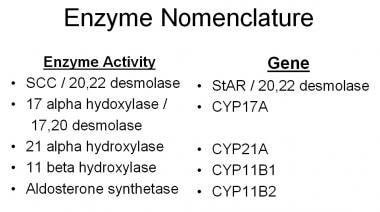

The phenotype depends on the degree or type of gene deletion or mutation and the resultant deficiency of the steroidogenic enzyme. The enzymes and corresponding genes are displayed in the image below.

Enzymes and genes involved in adrenal steroidogenesis.

Two copies of an abnormal gene are required for disease to occur, and not all mutations and partial deletions result in disease. The phenotype can vary from clinically inapparent disease (occult or cryptic adrenal hyperplasia) to a mild form of disease that is expressed in adolescence or adulthood (nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia) to severe disease that results in adrenal insufficiency in infancy with or without virilization and salt wasting (classic adrenal hyperplasia). The most common form of adrenal hyperplasia (due to a deficiency of 21-hydroxylase activity) is clinically divided into 3 phenotypes: salt wasting, simple virilizing, and nonclassic.

CYP21A is the gene that codes for 21-hydroxylase, CYP11B1 codes for 11-beta-hydroxylase, and CYP17 codes for 17-alpha-hydroxylase. Many of the enzymes involved in cortisol and aldosterone syntheses are cytochrome P450 (CYP) proteins.

A study by Ridder et al indicated that the comorbidity profile of adults with CAH is sex-specific. Adult females with CAH tended to have higher hemoglobin levels, a greater body mass index (BMI), lower insulin sensitivity, a prolonged E-wave deceleration time, and a higher E/e’ ratio, than did female controls. They also tended to have a lower self-reported quality of life. Adult males with CAH tended to have more cognitive complaints and higher scores on the Autism Spectrum Quotient questionnaire than did male controls. [10]

Frequency

United States

The most common form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia is due to mutations or deletions of CYP21A, resulting in 21-hydroxylase deficiency. This deficiency accounts for more than 90% of adrenal hyperplasia cases. Mutations or partial deletions that affect CYP21A are common, with estimated frequencies as high as 1 in 3 individuals in selected populations (eg, Ashkenazi Jews) to 1 in 7 individuals in New York City. The estimated prevalence is 1 case per 60 individuals in the general population.

Classic adrenal hyperplasia has an overall prevalence of 1 case per 16,000 population; however, in selected populations (eg, the Yupik of Alaska), the prevalence is as high as 1 case in 400 population. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia caused by 11-beta-hydroxylase deficiency accounts for 5-8% of all congenital adrenal hyperplasia cases.

International

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency is found in all populations. 11-beta-hydroxylase deficiency is more common in persons of Moroccan or Iranian-Jewish descent.

Mortality/Morbidity

The morbidity of the various forms of adrenal hyperplasia is best understood in the context of the steroidogenic pathway, shown below, used by the adrenal glands and gonads.

Steroidogenic pathway for cortisol, aldosterone, and sex steroid synthesis. A mutation or deletion of any of the genes that code for enzymes involved in cortisol or aldosterone synthesis results in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The particular phenotype that results depends on the sex of the individual, the location of the block in synthesis, and the severity of the genetic deletion or mutation.

The clinical phenotype can be understood by analyzing the location of the enzyme deficiency, the accumulation of precursor hormones, the products of those precursors when one enzyme pathway is ineffective, and the physiologic action of those hormones (see History).

A study by Halper et al of 42 children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia reported that total body bone mineral density was lower in these youngsters than in controls (0.81 g/cm2 vs 1.27 g/cm2, respectively). However, no significant differences in body composition, including with regard to visceral adipose tissue and android:gynoid ratio, were found between the two groups. [11]

A study by Yang and White indicated that in children with the salt-wasting form of 21-hydroxylase deficiency congenital adrenal hyperplasia, the risk of postdiagnostic hospitalization is greater in patients younger than 2 years (possibly resulting from a higher susceptibility to viral infections and a lower ability to cope with stress and dehydration) and those who need a greater daily dosage of fludrocortisone (perhaps because these patients are likely to have more severe disease). The study also found that children with noncommercial insurance were more likely to be hospitalized, possibly because they are more likely to experience social barriers to treatment compliance. [12]

A study by Herting et al indicated that medial temporal lobe volumes are smaller in young people with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, with the lateral nucleus of the amygdala, along with the hippocampal subiculum and CA1 subregion, particularly being affected. [13]

A study by Lim et al of Asian adults with congenital adrenal hyperplasia found that males had a 2.7-fold greater risk for hypertension, while women had a 2.0-fold increased risk for obesity. Adrenal limb thickness was significantly greater in men with obesity, while 17-hydroxyprogesterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels were significantly higher in women with obesity. Women with irregular periods also tended to have higher dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels. [14]

Severe forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia are potentially fatal if unrecognized and untreated because of the severe cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies that result in salt wasting, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, dehydration, and hypotension.

Epidemiology

Race

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia occurs among people of all races. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia secondary to CYP21A1 mutations and deletions is particularly common among the Yupik Eskimos.

Sex

Because all forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia are autosomal recessive disorders, both sexes are affected with equal frequency. However, because accumulated precursor hormones or associated impaired testosterone synthesis impacts sexual differentiation, the phenotypic consequences of mutations or deletions of a particular gene differ between the sexes.

Age

Classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia is generally recognized at birth or in early childhood because of ambiguous genitalia, salt wasting, or early virilization. Nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia is generally recognized at or after puberty because of oligomenorrhea or virilizing signs in females.

Prognosis

With adequate medical and surgical therapy, the prognosis is good. However, problems with psychological adjustment are common and usually stem from the genital abnormality that accompanies some forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

- Short stature and infertility are common.

- Gender identity in females with virilizing adrenal hyperplasia is usually female if female gender assignment is made early in life, if adequate medical and surgical support are provided, and if the family (and eventually the patient herself) is given adequate education to understand the disease.

- Females with virilizing adrenal hyperplasia may have more masculine interests.

- Females with adrenal hyperplasia have reduced fertility rates, but fertility is possible with good metabolic control.

- Early death may occur if patients are not provided with stress doses of glucocorticoid in times of illness, trauma, or surgery.

Patient Education

Educate the caretakers and patients about the nature of the disease in order for them to understand the importance of replacement of the deficient adrenal cortical hormones.

Patients must also understand the need for additional glucocorticoids in times of illness and stress in order to avoid an adrenal crisis.

Patients must know the importance of IM injections of glucocorticoids and be educated in the technique of IM administration.

Useful Web sites for patients and parents include the National Adrenal Diseases Foundation and the Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Research Education and Support (CARES) Foundation.

- Merke DP. Approach to the adult with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Mar. 93(3):653-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Turcu AF, Auchus RJ. The next 150 years of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015 Sep. 153:63-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Turcu AF, Auchus RJ. Adrenal steroidogenesis and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015 Jun. 44 (2):275-96. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Witchel SF. Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012 Jun. 19(3):151-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- New MI, Rapaport R. The adrenal cortex. In: Pediatric Endocrinology. Philadelphia, Pa:. WB Saunders. 1996:287.

- Purandare A, Godil MA, Prakash D, et al. Spontaneous adrenal hemorrhage associated with transient antiphospholipid antibody in a child. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001 Jun. 40(6):347-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Speiser PW, Azziz R, Baskin LS, Ghizzoni L, Hensle TW, Merke DP. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Sep. 95(9):4133-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Speiser PW, Arlt W, Auchus RJ, et al. Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to Steroid 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Nov 1. 103 (11):4043-88. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Poppas DP. Clitoroplasty in congenital adrenal hyperplasia: description of technique. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011. 707:49-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ridder LO, Balle CM, Skakkebæk A, et al. Endocrine, cardiac and neuropsychological aspects of adult congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2024 Jun. 100 (6):515-26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Halper A, Sanchez B, Hodges JS, et al. Bone mineral density and body composition in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018 Feb 20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yang M, White PC. Risk factors for hospitalization of children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017 Feb 13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Herting MM, Azad A, Kim R, Tyszka JM, Geffner ME, Kim MS. Brain Differences in the Prefrontal Cortex, Amygdala, and Hippocampus in Youth with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Apr 1. 105 (4):[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lim SG, Lee YA, Jang HN, et al. Long-Term Health Outcomes of Korean Adults With Classic Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021. 12:761258. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Torre JJ, Bloomgarden ZT, Dickey RA, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Endocr Pract. 2006 Mar-Apr. 12(2):193-222. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Carvalho LC, Brito VN, Martin RM, et al. Clinical, hormonal, ovarian, and genetic aspects of 46,XX patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to CYP17A1 defects. Fertil Steril. 2016 Jun. 105 (6):1612-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Auchus RJ. The backdoor pathway to dihydrotestosterone. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Nov. 15(9):432-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kamrath C, Hochberg Z, Hartmann MF, Remer T, Wudy SA. Increased activation of the alternative "backdoor" pathway in patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency: evidence from urinary steroid hormone analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Mar. 97(3):E367-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Auchus RJ, Miller WL. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia--more dogma bites the dust. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Mar. 97(3):772-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=omim.

- Fluck CE, Tajima T, Pandey AV, et al. Mutant P450 oxidoreductase causes disordered steroidogenesis with and without Antley-Bixler syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004 Mar. 36(3):228-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Longui CA, Kochi C, Calliari LE, Modkovski MB, Soares M, Alves EF, et al. Near-final height in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia treated with combined therapy using GH and GnRHa. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2011 Nov. 55(8):661-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lin-Su K, Harbison MD, Lekarev O, Vogiatzi MG, New MI. Final adult height in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia treated with growth hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jun. 96(6):1710-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Roth JD, Casey JT, Whittam BM, et al. Characteristics of Female Genital Restoration Surgery for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Using a Large Scale Administrative Database. Urology. 2018 Mar 2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dangle PP, Lee A, Chaudhry R, Schneck FX. Surgical Complications Following Early Genitourinary Reconstructive Surgery for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia-Interim Analysis at 6 Years. Urology. 2016 Nov 23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gunther DF, Bukowski TP, Ritzen EM, et al. Prophylactic adrenalectomy of a three-year-old girl with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: pre- and postoperative studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997 Oct. 82(10):3324-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Maccabee-Ryaboy N, Thomas W, Kyllo J, et al. Hypertension in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016 Apr 22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aycan Z, Akbuga S, Cetinkaya E, et al. Final height of patients with classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Turk J Pediatr. 2009 Nov-Dec. 51(6):539-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Riehl G, Reisch N, Roehle R, Claahsen van der Grinten H, Falhammar H, Quinkler M. Bone mineral density and fractures in congenital adrenal hyperplasia: Findings from the dsd-LIFE study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2020 Apr. 92 (4):284-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Garner PR. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 1998 Dec. 22(6):446-56. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vos AA, Bruinse HW. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia: do the benefits of prenatal treatment defeat the risks?. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2010 Mar. 65(3):196-205. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Carlson AD, Obeid JS, Kanellopoulou N, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia: update on prenatal diagnosis and treatment. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999 Apr-Jun. 69(1-6):19-29. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Joint LWPES/ESPE CAH Working Group. Consensus statement on 21-hydroxylase deficiency from the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Sep. 87(9):4048-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Meyer-Bahlburg HF, Dolezal C, Haggerty R, Silverman M, New M. Cognitive Outcome of Offspring from Dexamethasone-Treated Pregnancies at Risk for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012 May 1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hirvikoski T, Nordenstrom A, Wedell A, Ritzen M, Lajic S. Prenatal dexamethasone treatment of children at risk for congenital adrenal hyperplasia: the Swedish experience and standpoint. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Jun. 97 (6):1881-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- White PC. Neonatal screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009 Sep. 5(9):490-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Janzen N, Riepe FG, Peter M, Sander S, Steuerwald U, Korsch E, et al. Neonatal screening: identification of children with 11ß-hydroxylase deficiency by second-tier testing. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012. 77(3):195-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barone MA, ed. The Harriet Lane Handbook. St Louis, Mo: Mosby-Year Book; 1996. 681.