Pediatric Rectal Prolapse: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

Rectal prolapse refers to the circumferential extrusion of some or the entire rectal wall through the external anal sphincter. [1] Although, less common in Western societies, pediatric rectal prolapse is a relatively common benign disorder in children. However, without proper treatment, it can become a lifestyle limiting chronic condition. Most cases are self-limiting, with prompt resolution after conservative measures aimed at correcting the associated underlying process.

In children, rectal prolapse should always be considered a presenting sign of an underlying condition, and not a disease entity unto itself. Rectal prolapse starts as a mucosal extrusion from the mucocutaneous junction, which may eventually progress to full-thickness prolapse.

Rectal prolapse starts as a mucosal extrusion from the mucocutaneous junction, which may eventually progress to full-thickness prolapse. It is one of the first surgical entities ever described in medicine. (see the image below).

Image of young patient with full-thickness rectal prolapse with multiple circular folds seen on exposed mucosa.

Rectal prolapse and its etiology were first described in 1912 by Moschcowitz. Rectal prolapse in childhood was first highlighted in 1939 by Lockhart and Mummery [2] , who attributed the condition to malnutrition and careless nursing, but also acknowledged diarrheal disease and wasting illnesses as contributing factors. Lockhart-Mummery’s preferred operative treatment was linear cauterization of the prolapsed rectum, with recurrences treated by 5% phenol injection.

Loss of the normal sacral curvature that causes a vertical tube between the rectum and the anal canal has been described as a causative factor. Straining during defecation predisposes children with constipation, diarrhea, or parasitosis to prolapse, as does childhood laxative usage. About 60%-70% of patients have fecal incontinence. [3] The prolapse can spontaneously reduce or may require digital reduction.

Background

One classification of rectal prolapse divides the entity into true prolapse (protrusion of all layers of the rectum) and procidentia (herniation of only the mucosa). However, this classification is confusing and nonspecific and therefore, fallen out of use.

The most used classification for rectal prolapse was described in 1971 by Altemeier et al, who divided the entity into the following types [4] :

Type I Protrusion of redundant mucosa, termed false prolapse; usually associated with hemorrhoids

Type II Intussusception without sliding hernia of the cul-de-sac; it occupies the rectal ampulla but does not continue through the anal canal; the most common symptom is fecal incontinence, but solitary ulcers in the anterior rectal mucosa can be seen

Type III Complete, full-thickness rectal wall prolapse, associated with a sliding hernia of the Douglas pouch. It is the most frequent type.

Types II and III can be further subdivided into three degrees [5] :

First degree prolapse includes the mucocutaneous junction. The length of the protrusion from the anal verge usually is greater than 5cm.

Second degree prolapse occurs without involvement of the mucocutaneous junction. The length of the protrusion from the anal verge usually is between 2 and 5 cm.

Third degree prolapse is internal concealed or occult, and does not pass through the anal verge.

For the particular case of rectal prolapse occurring after the surgical correction of an anorectal malformation, [6] the entity can also be classified as:

Minimal, when the rectal mucosa was visible at the anal verge with Valsalva manoeuvre

Moderate, when there was a protrusion of the rectal mucosa inferior to 5 mm without the Valsalva manoeuvre; and

Evident, when the mucosal protrusion was greater than 5 mm without the Valsalva manoeuvre

The entity can also be categorized as circumferential,when it affects the rectum for 360o and hemi-circumferential, when the rectum is affected for less than 180o. [6] Most patients (77%) with rectal prolapse presenting after anorectoplasty can be successfully managed with conservative treatment. [6]

Anatomy

The anal canal extends cephalad from the anal verge to the anorectal ring. The rectum extends from this point to the sacral promontory.

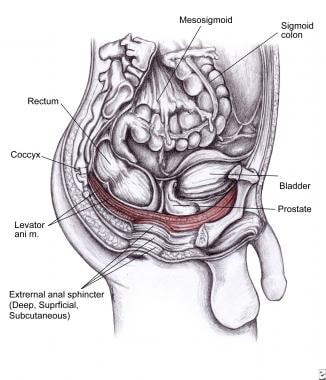

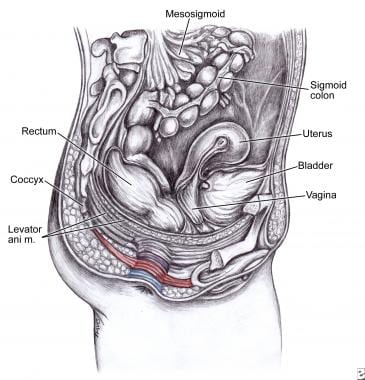

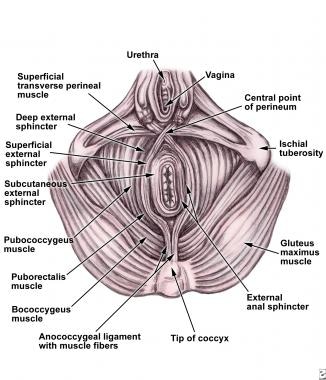

Upon histologic examination, the anal canal consists of mucosa, submucosa, and 2 muscular layers: the internal anal sphincter (IAS), which is a continuation of the circular muscle of the rectum, and [3] the external anal sphincter (EAS), which lies outside the IAS as an elliptic cylinder, continuous with the puborectalis muscle superiorly. The surgical anal canal includes this entire muscular sphincter mechanism (see the images below).

Levator ani muscle is shown in red. It includes ileococcygeus (stretches during defecation and labor), pubococcygeus (maintains integrity of pelvic floor), and puborectalis muscles (closes the anorectal canal as a sling).

Deep, superficial, and subcutaneous external sphincter.

Anatomy of internal and external anal sphincter mechanisms.

The many and varied procedures described for the treatment of rectal prolapse attempt to create a fixation of the anorectal mucosa to the submucosa, or the rectal wall to perirectal tissues.

Pathophysiology

Children are predisposed to rectal prolapse due to anatomic considerations: A pelvic floor defect with levator ani muscle diastasis and a deep endopelvic fascia represent the pathophysiology of the disease. Patients with rectal prolapse have lost the normal semi-horizontal rectal position; they also have weak muscle insertions to the pelvic walls and sacrum, an abnormally deep Douglas pouch and Houston’s valves absence in approximately 75% of infants younger than 1 year of age. [7] A redundant rectosigmoid and weaker / wider anal sphincter are common.

The normal resting tone of the anal sphincter decreases in response to rectal distention. In 1962, Porter found that patients with rectal prolapse have a profound and lengthy response and weakened tone of the levator ani muscles. [8] Whether this is a causative factor or a secondary finding is not clear, since the prolapse begins above the pelvic musculature. Most recently, information has suggested that rectal prolapse can be developed as a result of circumferential intussusception of the upper rectum and rectosigmoid colon. [7]

Rectal prolapse has been associated with a myriad of conditions, including:

- Increased intraabdominal pressure due to straining (as often occurs in toilet training and constipation)

- Parasitic disease (the most common cause of rectal prolapse in developing countries)

- Neoplastic disease

- Malnutrition (loss of ischiorectal fat pad) Worldwide, this is possibly the most common condition associated with pediatric rectal prolapse; the loss of ischiorectal fat reduces perirectal support

- Ulcerative colitis

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Meningomyelocele

- Pertussis

- Surgical repair of anorectal malformation

- Fecal incontinence and diarrhea [9, 10]

- Chronic constipation [11]

- Neuromuscular disorders

- Mental challenge [12]

- Poor sacral root innervation (Spina bifida)

- Bladder or cloacal exstrophy [13]

- Scleroderma [14]

- Hirschsprung disease (especially in ultrashort aganglionic segment, which acts as subocclusion, favoring prolapse) [15]

- Rectal polyps (the polyp acts as a leading point) [16]

- Cystic fibrosis [17]

- Shigellosis in neonates [1]

- Diarrheal disease (Infection by organisms that increases bowel motility) [7]

Cystic fibrosis (CF) deserves special attention as it may cause rectal prolapse in children. In the past, rectal prolapse was described in up to 20% of individuals with cystic fibrosis. However, current reports estimate an incidence of 3% of children with the disease. [18, 19] Potential mechanisms include bulky bowel movements, coughing paroxysms, and undernutrition. It is most frequently seen in toddlers, but it can occur at any age (triggered by cough). Clinical clues to cystic fibrosis include oily, malodorous, or floating stools; poor growth; wheezing or other respiratory symptoms; and digital clubbing. The absence of respiratory symptoms and normal findings upon physical examination do not necessarily exclude this diagnostic possibility. Sweat chloride test should be performed in order to rule out cystic fibrosis.

Most cases of childhood rectal prolapse occur in children younger than 4 years, with the highest incidence during the first year of life. Anatomic considerations related to this early presentation include the vertical course of the rectum along the straight surface of the sacrum, a relatively low position of the rectum in relation to other pelvic organs, increased mobility of the sigmoid colon, relative lack of support by the levator ani muscle, loose attachment of the rectal mucosa to the underlying muscularis, and absence of Houston valves, seen in about 75% of infants.

Etiology

Several predisposing factors have been identified, chronic constipation and straining being most common (52%). Other causes include diarrhea (15%), [9] rectal parasites, [20] malnutrition, [7] neuromuscular and pelvic nerve disorders, myelomeningocele, bladder and cloacal exstrophy, Hirschsprung disease, behavioral and psychological disorders, [21] high anorectal malformations, [22] cystic fibrosis, chronic respiratory infections and cough, [23] lymphoid hyperplasia, rectal polyps, and shigellosis. [24] Rectal prolapse has also been described in a case of Clostridium difficile –associated pseudomembranous colitis in a child. [22]

Hill et al. evaluated 39 patients for associated behavioral/psychiatric disorders. Of these, they identified 21 (54%) children with one or more behavioral or psychological disorders (ADHD, anxiety disorder, depression, encopresis/stool withholding). They concluded there’s a high rate (over 50%) incidence of behavioral and psychological disorders in older (3-18 years) children presenting with rectal prolapse. However, there is scant published literature identifying a high rate of BPD in prolapsed children. [25]

Broden and Snellman demonstrated by cineradiography, that the entity implies a circumferential intussusception of the rectum, with its origin three inches above the anal margin. [26]

Epidemiology

In adults, rectal prolapse is six times more common in females than in males. 75% of patients have history of constipation, which stretches the pelvic floor and the anal sphincter mechanism, predisposing them to the disease.

In children, incidence is higher during the first year of life, after which it becomes increasingly infrequent. It is slightly more common in boys than in girls and usually occurs between infancy and 4 years of age.

Rentea and St. Peter, proposed the following risk factors for rectal prolapse [7] :

- Chronic constipation 28%

- Neurologic or anatomic conditions 24%

- Diarrheal disease 20%

- No underlying cause 17%

- Cystic Fibrosis 11%

As mentioned before, the cystic fibrosis group deserves special interest. An earlier review of CF revealed that 23% of patients with CF experienced rectal prolapse and that 78% of these patients experiencing rectal prolapse before the diagnosis of CF. This led to the recommendation that CF should be considered in a child with rectal prolapse of unknown etiology. [1]

Prognosis

Most cases reduce spontaneously. Otherwise, venous stasis, edema, and ulceration ensure. Longstanding or frequent recurrent prolapse episodes lead to proctitis.

Approximately 10% of patients who experience rectal prolapse as children continue to be symptomatic into adulthood. Over 90% of children who prolapsed during the first 3 years of life, respond to conservative treatment by age 6. It is important to achieve this early because the more episodes of rectal prolapse, especially, those cases that do not reduce spontaneously or have difficult reduction, demonstrate a lesser response to conservative management. [27] Spontaneous resolution is much less likely in children who develop their first episode of prolapse after age 4 years. After a surgical rectopexy, continence is achieved in 92% of patients. Resective procedures demonstrate lower recurrence rates.

Recovery of continence after surgery is not immediate, it may take up to a year.

Nwako et al reported a 100% success rate with the Lockhart-Mummery procedure, which involves packing the presacral space with gauze through a posterior approach, with excision of the prolapsed mucosa. [24]

Hight et al recommend linear cauterization of the rectal mucosa, with a 98% success rate in 72 patients. [28]

- El-Chammas KI, Rumman N, Goh VL, Quintero D, Goday PS. Rectal Prolapse and Cystic Fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug 25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lockhart-Mummery JP. Surgical procedures in general practice. Br Med J. 1939. 1:345-7.

- Williams JG, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM. Treatment of rectal prolapse in the elderly by perineal rectosigmoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992 Sep. 35(9):830-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Altemeier WA, Culbertson WR, Schowengerdt C, Hunt J. Nineteen years' experience with the one-stage perineal repair of rectal prolapse. Ann Surg. 1971 Jun. 173(6):993-1006. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Rana Kronfol. Rectal prolapse in children. UpToDate. Available at https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rectal-prolapse-in-children?search=rectal%20prolapse&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~49&usage_type=default&display_rank=2. Sep 2017.; Accessed: 30 Oct 2019.

- Brisighelli G, Di Cesare A, Morandi A, Paraboschi I, Canazza L, Consonni D, et al. Classification and management of rectal prolapse after anorectoplasty for anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014 Aug. 30 (8):783-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rentea RM, St Peter SD. Pediatric Rectal Prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018 Mar. 31 (2):108-116. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Porter NH. A physiological study of the pelvic floor in rectal prolapse. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1962 Dec. 31:379-404. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Mann CV. Rectal prolapse. Morson BC, Heinemann W, eds. Diseases of the Colon, Rectum and Anus. London: Medical Books; 1969. 238.

- Hinninghofen H, Enck P. Fecal incontinence: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003 Jun. 32(2):685-706. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Katz C, Drongowski RA, Coran AG. Long-term management of chronic constipation in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1987 Oct. 22(10):976-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ponge T, Bruley des Varannes S. [Digestive involvement of scleroderma]. Rev Prat. 2002 Nov 1. 52(17):1896-900. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Candela G, Grillo M, Campione M, Casaburi V, Maschio A, Sciano D, et al. [Complete rectal prolapse in a patient with Hirschsprung disease: a clinical case]. G Chir. 2003 Aug-Sep. 24(8-9):289-94. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sanaka MR, Ferguson DR, Ulrich S, Sargent R. Polyp associated with rectal prolapse. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Jun. 59(7):871-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Orenstein DM, Winnie GB, Altman H. Cystic fibrosis: a 2002 update. J Pediatr. 2002 Feb. 140(2):156-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Huskins WC, Griffiths JK, Faruque AS, Bennish ML. Shigellosis in neonates and young infants. J Pediatr. 1994 Jul. 125(1):14-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rock MJ. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2007 Jun. 28(2):297-305. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Adedayo O, Nasiiro R. Intestinal parasitoses. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004 Jan. 96(1):93-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Brisighelli G, Di Cesare A, Morandi A, Paraboschi I, Canazza L, Consonni D, et al. Classification and management of rectal prolapse after anorectoplasty for anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014 Aug. 30(8):783-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bush A. Recurrent respiratory infections. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009 Feb. 56(1):67-100, x. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hill SR, Ehrlich PF, Felt B, Dore-Stites D, Erickson K, Teitelbaum DH. Rectal prolapse in older children associated with behavioral and psychiatric disorders. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015 Aug. 31 (8):719-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Huang SC, Yang YJ, Lee CT. Rectal prolapse in a child: an unusual presentation of Clostridium difficile-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011 Apr. 52(2):110-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brodén B, Snellman B. Procidentia of the rectum studied with cineradiography. A contribution to the discussion of causative mechanism. Dis Colon Rectum. 1968 Sep-Oct. 11(5):330-47. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nwako F. Rectal Prolapse in Nigerian Children. Int Surg. 1975 May. 60(5):284-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Villarreal M, Brum P. [Rectal prolapse in a neonate with Shigella diarrhea]. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2010 Feb. 108(1):e17-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bequet E, Stiennon L, Lhomme A, Piette C, Hoyoux C, Rausin L, et al. [Rectal prolapse revealing a tumor: The role of abdominal ultrasound]. Arch Pediatr. 2016 Jul. 23 (7):723-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Antao B, Bradley V, Roberts JP, Shawis R. Management of rectal prolapse in children. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005 Aug. 48(8):1620-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hight DW, Hertzler JH, Philippart AI, Benson CD. Linear cauterization for the treatment of rectal prolapse in infants and children. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982 Mar. 154(3):400-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sarmast MH, Askarpour S, Peyvasteh M, Javaherizadeh H, Mooghehi-Nezhad M. Rectal prolapse in children: a study of 71 cases. Prz Gastroenterol. 2015. 10 (2):105-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khushbakht S, ul Haq A. Rectal Duplication Cyst: A Rare Cause of Rectal Prolapse in a Toddler. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015 Dec. 25 (12):909-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Felt-Bersma RJ, Tiersma ES, Cuesta MA. Rectal prolapse, rectal intussusception, rectocele, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, and enterocele. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008 Sep. 37(3):645-68, ix. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jason S.Frischer, MD, Beth Rymeski, DO. Complications in colorectal surgery. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 2016. 25:380–387. [Full Text].

- Rashid Z, Basson MD. Association of rectal prolapse with colorectal cancer. Surgery. 1996 Jan. 119(1):51-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bennett W. Calder and Robert A. Cina. Perianal Disease - Rectal Prolapse. Peter Mattei. Fundamentals of Pediatric Surgery. Second Edition. ISBN 978-3-319-27441-6: Springer; 2017. 525-530.

- Campbell AM, Murphy J, Charlesworth PB, Bhan C, Jarvi K, Power N, et al. Dynamic MRI (dMRI) as a guide to therapy in children and adolescents with persistent full thickness rectal prolapse: a single centre review. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Mar. 48 (3):607-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mäkelä-Kaikkonen J, Rautio T, Pääkkö E, Biancari F, Ohtonen P, Mäkelä J. Robot-assisted vs laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for external or internal rectal prolapse and enterocele: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2016 Oct. 18 (10):1010-1015. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mugie SM, Bates DG, Punati JB, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C, Mousa HM. The value of fluoroscopic defecography in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of defecation disorders in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2014 Sep 30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Norton C. Fecal incontinence and biofeedback therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008 Sep. 37(3):587-604, viii. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Li M, Jiang T, Peng P, Yang X. MR Defecography in Assessing Functional Defecation Disorder: Diagnostic Value of the Defecation Phase in Detection of Dyssynergic Defecation and Pelvic Floor Prolapse in Females. Digestion. 2019. 100 (2):109-116. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ramage L, Simillis C, Yen C, Lutterodt C, Qiu S, Tan E, et al. Magnetic resonance defecography versus clinical examination and fluoroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2017 Dec. 21 (12):915-927. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chan WK, Kay SM, Laberge JM, Gallucci JG, Bensoussan AL, Yazbeck S. Injection sclerotherapy in the treatment of rectal prolapse in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Feb. 33(2):255-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Festen S, van Geloven AA, D'Hoore A, Lindsey I, Gerhards MF. Controversy in the treatment of symptomatic internal rectal prolapse: suspension or resection?. Surg Endosc. 2011 Jun. 25(6):2000-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ramanujam PS, Venkatesh KS. Management of acute incarcerated rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992 Dec. 35(12):1154-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Coburn WM 3rd, Russell MA, Hofstetter WL. Sucrose as an aid to manual reduction of incarcerated rectal prolapse. Ann Emerg Med. 1997 Sep. 30(3):347-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wijffels NA, Collinson R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. What is the natural history of internal rectal prolapse?. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Aug. 12(8):822-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Seenivasagam T, Gerald H, Ghassan N, Vivek T, Bedi AS, Suneet S. Irreducible rectal prolapse: emergency surgical management of eight cases and a review of the literature. Med J Malaysia. 2011 Jun. 66(2):105-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tou S, Brown SR, Nelson RL. Surgery for complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Nov 24. CD001758. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brown AJ, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Finlay IG. Strategy for selection of type of operation for rectal prolapse based on clinical criteria. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 Jan. 47(1):103-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ripstein CB, Lanter B. Etiology and surgical therapy of massive prolapse of the rectum. Ann Surg. 1963 Feb. 157:259-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Dattani PG. 15th International Conference on AIDS. Bangkok, Thailand: Jul, 2004. 15: abstract no. B11748.

- Ezer SS, Kayaselçuk F, Oguzkurt P, Temiz A, Ince E, Hicsonmez A. Comparative effects of different sclerosing agents used to treat rectal prolapse: an experimental study in rats. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 Aug. 48(8):1738-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mugie SM, Bates DG, Punati JB, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C, Mousa HM. The value of fluoroscopic defecography in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of defecation disorders in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2015 Feb. 45 (2):173-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yoon SG. Rectal prolapse: review according to the personal experience. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011 Jun. 27(3):107-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ashcraft KW, Garred JL, Holder TM, Amoury RA, Sharp RJ, Murphy JP. Rectal prolapse: 17-year experience with the posterior repair and suspension. J Pediatr Surg. 1990 Sep. 25(9):992-4; discussion 994-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chiang LW, Lee SY. Laparoscopic management for non-traumatic colon perforation in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013 Apr. 29 (4):353-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ibáñez V, Gutiérrez C, García-Sala C, Lluna J, Barrios JE, Roca A, et al. [The prolapse of the rectum. Treatment with fibrin adhesive]. Cir Pediatr. 1997 Jan. 10(1):21-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fahmy MA, Ezzelarab S. Outcome of submucosal injection of different sclerosing materials for rectal prolapse in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004 May. 20(5):353-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Abes M, Sarihan H. Injection sclerotherapy of rectal prolapse in children with 15 percent saline solution. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Apr. 14(2):100-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zganjer M, Cizmic A, Cigit I, et a;. Treatment of rectal prolapse in children with cow milk injection sclerotherapy: 30-year experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Feb 7. 14(5):737-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lomas MI, Cooperman H. Correction of rectal procidentia by use of polypropylene mesh (Marlex). Dis Colon Rectum. 1972 Nov-Dec. 15(6):416-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saleem MM, Al-Momani H. Acute scrotum as a complication of Thiersch operation for rectal prolapse in a child. BMC Surg. 2006 Dec 28. 6:19. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chauhan K, Gan RW, Singh S. Successful treatment of recurrent rectal prolapse using three Thiersch sutures in children. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Nov 25. 2015:[QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- El-Sibai O, Shafik AA. Cauterization-plication operation in the treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2002 Apr. 6(1):51-4; discussion 54. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sander S, Vural O, Unal M. Management of rectal prolapse in children: Ekehorn's rectosacropexy. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999. 15(2):111-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schepens MA, Verhelst AA. Reappraisal of Ekehorn's rectopexy in the management of rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1993 Nov. 28(11):1494-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Joshi AA, Milanovic DM. Delorme’s procedure for rectal prolapse in a child refractory to conservative treatment and rectal suspension. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006. 21:395-6.

- De la Torre L, Zornoza-Moreno M, Cogley K, Calisto JL, Wehrli LA, Ruiz-Montañez A, et al. Transanal endorectal approach for the treatment of idiopathic rectal prolapse in children: Experience with the modified Delorme's procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2018 Oct 12. 146 (1):87-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lieberth M, Kondylis LA, Reilly JC, Kondylis PD. The Delorme repair for full-thickness rectal prolapse: a retrospective review. Am J Surg. 2009 Mar. 197(3):418-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lee JI, Vogel AM, Suchar AM, Glynn L, Statter MB, Liu DC. Sequential linear stapling technique for perineal resection of intractable pediatric rectal prolapse. Am Surg. 2006 Dec. 72(12):1212-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yamana T, Iwadare J. Mucosal plication (Gant-Miwa procedure) with anal encircling for rectal prolapse--a review of the Japanese experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003 Oct. 46(10 Suppl):S94-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lasheen AE. Closed rectosacropexy for rectal prolapse in children. Surg Today. 2003. 33(8):642-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gomes-Ferreira C, Schneider A, Philippe P, Lacreuse I, Becmeur F. Laparoscopic modified Orr-Loygue mesh rectopexy for rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Feb. 50 (2):353-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ismail M, Gabr K, Shalaby R. Laparoscopic management of persistent complete rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Mar. 45(3):533-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kairaluoma MV, Viljakka MT, Kellokumpu IH. Open vs. laparoscopic surgery for rectal prolapse: a case-controlled study assessing short-term outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003 Mar. 46(3):353-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Delaney CP. Laparoscopic management of rectal prolapse. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007 Feb. 11(2):150-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Awad K, El Debeiky M, AbouZeid A, Albaghdady A, Hassan T, Abdelhay S. Laparoscopic Suture Rectopexy for Persistent Rectal Prolapse in Children: Is It a Safe and Effective First-Line Intervention?. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2016 Apr. 26 (4):324-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Senagore AJ. Management of rectal prolapse: the role of laparoscopic approaches. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2003 Dec. 10(4):197-202. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Hoore A, Penninckx F. Laparoscopic ventral recto(colpo)pexy for rectal prolapse: surgical technique and outcome for 109 patients. Surg Endosc. 2006 Dec. 20(12):1919-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saxena AK, Metzelder ML, Willital GH. Laparoscopic suture rectopexy for rectal prolapse in a 22-month-old child. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004 Feb. 14(1):33-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Koivusalo AI, Pakarinen MP, Rintala RI, Seuri R. Dynamic defecography in the diagnosis of paediatric rectal prolapse and related disorders. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012 Aug. 28(8):815-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Stonelake S, Gee O, McArthur D, Jester I. Laparoscopic Protack™ rectopexy: Early experience of a novel technique for full thickness rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2018 Oct. 53 (10):2077-2080. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gupta PJ. Treatment of rectal prolapse with radiofrequency ablation and plication--a new surgical technique. Acta Chir Belg. 2007 Sep-Oct. 107(5):535-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nyström PO, Qvist N, Raahave D, Lindsey I, Mortensen N. Randomized clinical trial of symptom control after stapled anopexy or diathermy excision for haemorrhoid prolapse. Br J Surg. 2010 Feb. 97(2):167-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhang M. Thirty-six cases of infantile proctoptosis treated by extremely shallow puncture. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002 Mar. 22(1):33-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Van Heest R, Jones S, Giacomantonio M. Rectal prolapse in autistic children. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Apr. 39(4):643-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pearl RH, Ein SH, Churchill B. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for pediatric recurrent rectal prolapse. J Pediatr Surg. 1989 Oct. 24(10):1100-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Godbole P, Botterill I, Newell SJ, Sagar PM, Stringer MD. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in children. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2000 Dec. 45(6):411-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Savoye-Collet C, Koning E, Dacher JN. Radiologic evaluation of pelvic floor disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008 Sep. 37(3):553-67, viii. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lesher AP, Hill JG, Schabel SI, Morgan KA, Hebra A. An unusual pediatric case of chronic constipation and rectosigmoid prolapse diagnosed by video defecography. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 May. 45(5):1050-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shin T, Rafferty JF. Laparoscopy for benign colorectal diseases. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010 Feb. 23(1):42-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Potter DD, Bruny JL, Allshouse MJ, Narkewicz MR, Soden JS, Partrick DA. Laparoscopic suture rectopexy for full-thickness anorectal prolapse in children: an effective outpatient procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Oct. 45(10):2103-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Laituri CA, Garey CL, Fraser JD, Aguayo P, Ostlie DJ, St Peter SD. 15-Year experience in the treatment of rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Aug. 45(8):1607-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shalaby R, Ismail M, Abdelaziz M, Ibrahem R, Hefny K, Yehya A. Laparoscopic mesh rectopexy for complete rectal prolapse in children: a new simplified technique. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010 Aug. 26(8):807-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rittmeyer C, Nakayama D, Ulshen MH. Lymphoid hyperplasia causing recurrent rectal prolapse. J Pediatr. 1997 Sep. 131(3):487-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hussein AM, Helal SF. Schistosomal pelvic floor myopathy contributes to the pathogenesis of rectal prolapse in young males. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 May. 43(5):644-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Carrada-Bravo T. [Massive childhood trichocephaliasis]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2002 Jul-Sep. 67(3):212. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pancharoen C, Likitnukul S, Chongsrisawat V, Vivatvekin B, Bhattarakosol P, Suwangool P, et al. Rectal prolapse associated with cytomegalovirus pseudomembranous colitis in a child infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003 Sep. 34(3):583-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kuiper RJ, de Jong JR, Kneepkens CM. [There is something coming out of the anus of my child]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2011. 155:A2735. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Akkoyun I. The advantages of using photographs and video images in telephone consultations with a specialist in paediatric surgery. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2012 May-Aug. 9(2):128-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Akkoyun I, Akbiyik F, Soylu SG. The use of digital photos and video images taken by a parent in the diagnosis of anal swelling and anal protrusions in children with normal physical examination. J Pediatr Surg. 2011 Nov. 46(11):2132-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fang SH, Cromwell JW, Wilkins KB, Eisenstat TE, Notaro JR, Alva S. Is the abdominal repair of rectal prolapse safer than perineal repair in the highest risk patients? An NSQIP analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012 Nov. 55(11):1167-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dolejs SC, Sheplock J, Vandewalle RJ, Landman MP, Rescorla FJ. Sclerotherapy for the management of rectal prolapse in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2017 Oct 10. 32 (1):36-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Khalil. Rectal Prolapse and Cystic Fibrosis.

Author

Jaime Shalkow, MD, FACS Pediatric Surgical Oncologist, ABC Cancer Center; Associated Researcher, Anahuac University, Mexico

Jaime Shalkow, MD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, International Society of Paediatric Surgical Oncology, International Society of Pediatric Oncology, Latin American Pediatric Surgical Oncology Group, Mexican Association of Pediatric Surgery, Mexican Society of Oncology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Coauthor(s)

Pablo Magaña Mainero, MD General and Laparoscopic Surgeon, ABC Medical Center; Assistant Director, General Hospital of Mexico “Dr Eduardo Liceaga”, Mexico

Pablo Magaña Mainero, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Mexican Association for Endoscopic Surgery, Mexican Association of General Surgery, Mexican Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Andrés Olivares Ronces, MD Assistant Surgeon, Centro Médico ABC Campus Observatorio, Mexico

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Carmen Cuffari, MD Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology/Nutrition, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Carmen Cuffari, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Gastroenterology, American Gastroenterological Association, North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

Disclosure: Received honoraria from Prometheus Laboratories for speaking and teaching; Received honoraria from Abbott Nutritionals for speaking and teaching. for: Abbott Nutritional, Abbvie, speakers' bureau.

Additional Contributors

Ignacio Guzman, MD Medical Staff, Medical and Surgical Patient Care, General Hospital of Mexico; Medical Staff, Pediatric Surgical Oncology, National Institute of Pediatrics, Mexico

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Joyce Vazquez-Braverman, MD Instructor of ACLS, BLS, and Heartsavers, American Heart Assocation

Joyce Vazquez-Braverman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Issac Octavio Vargas Olmos Universidad Anahuac, Mexico

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Shahida Bibi, MD Resident Physician, Department of Surgery, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Robert Baldassano, MD Director, Center for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Robert Baldassano, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Gastroenterological Association, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Deborah F Billmire, MD Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Indiana University Medical Center

Deborah F Billmire, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Surgeons, American Pediatric Surgical Association, Phi Beta Kappa, and Society of Critical Care Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Rebeccah Brown, MD Associate Director of Trauma Services, Associate Professor, Department of Clinical Surgery and Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Hospital

Rebeccah Brown, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, and American Medical Women's Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Frank Cunningham, Jr, MD, FAAP, FACEP Director, Division of Emergency Pediatrics, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

Frank Cunningham, Jr, MD, FAAP, FACEP is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Joel A Friedlander, DO, MBe Instructor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Fellow, Pediatric Gastroenterology, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Joel A Friedlander, DO, MBe is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Osteopathic Pediatricians, American Gastroenterological Association, American Medical Association, American Osteopathic Association, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Leon M Garner, DO, MPH Staff Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, North Broward Medical Center

Leon M Garner, DO, MPH is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Harsh Grewal, MD, FACS, FAAP Professor of Surgery and Pediatrics, Temple University School of Medicine; Chief, Section of Pediatric Surgery, Temple University School of Medicine

Harsh Grewal, MD, FACS, FAAP is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Surgeons, American Pediatric Surgical Association, Association for Surgical Education, Children's Oncology Group, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, International Pediatric Endosurgery Group, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons, and SouthwesternSurgical Congress

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Marc S Lessin, MD Consulting Surgeon, Children's Surgical Associates, PC

Marc S Lessin, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons and American Pediatric Surgical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

B UK Li, MD Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Director, Pediatric Fellowships and Gastroenterology Fellowship, Medical Director, Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Cyclic Vomiting Program, Medical College of Wisconsin; Attending Gastroenterologist, Children's Hospital of Wisconsin

B UK Li, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Gastroenterological Association, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Maria Rebello Mascarenhas, MBBS Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Section Chief of Nutrition, Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Director, Nutrition Support Service, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Maria Rebello Mascarenhas, MBBS is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.