Carcinoid Tumor: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Practice Essentials

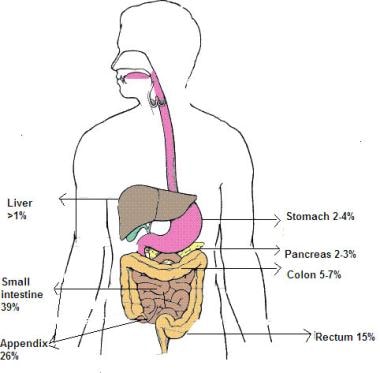

Carcinoid tumors are of neuroendocrine origin and derived from primitive stem cells in the gut wall, especially the appendix. [1, 2, 3, 4] They can be seen in other organs, [5] including the lungs, [6] mediastinum, thymus, [7] liver, bile ducts, [8] pancreas, [9] bronchus, [10, 11] ovaries, [12] prostate, [13] and kidneys (see the image below). While carcinoid tumors have a tendency to grow slowly, they have a potential for metastasis.

Distribution of carcinoid tumors.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of carcinoid tumors vary greatly. Carcinoid tumors can be "nonfunctioning" presenting as a tumor mass or "functioning" i.e. producing several biopeptides causing carcinoid syndrome. The sign and symptoms of a "nonfunctioning" tumor depend on the tumor location and size as well as on the presence of metastases. Therefore, findings range from no tumor-related symptoms (most carcinoid tumors) to full symptoms of carcinoid syndrome (primarily in adults).At times, the tumor is found as an incidental finding in a histopathologic examination. [14] Due to their vague and intermittent symptoms, diagnosis of carcinoid tumors may be delayed, especially in children, in whom the tumor is rare and the diagnosis is unexpected.

Signs and symptoms seen in larger tumors may include the following:

- Periodic abdominal pain: Most common presentation for a small intestinal carcinoid; often associated with malignant carcinoid syndrome

- Cutaneous flushing: Early and frequent (94%) symptom; typically affects head and neck; often associated with an unpleasant warm feeling, itching, rash, sweating, palpitation, upper-body erythema and edema, salivation, diaphoresis, lacrimation, and diarrhea

- Diarrhea and malabsorption (84%): Watery, frothy, or bulky stools, gastrointestinal (GI) bleed or steatorrhea; may or may not be associated with abdominal pain, flushing, and cramps

- Cardiac manifestations (60%): Valvular heart lesions, fibrosis of the endocardium; may lead to heart failure with tachycardia and hypertension

- Wheezing or asthmalike syndrome (25%): Due to bronchial constriction; some tremors are relatively indolent and result in chronic symptoms such as cough and dyspnea [15, 16]

- Pellagra with scale-like skin lesions, diarrhea and mental disturbances

- Carcinoid crisis can be the most serious symptom of carcinoid tumors and can be life-threatening. It can occur suddenly, after stress, or following chemotherapy and anesthesia. [17]

Classification

Carcinoid tumors generally are classified based on the location in the primitive gut that gives rise to the tumor, as follows:

- Foregut carcinoid tumors: Divided into sporadic primary tumors (lung, bronchus, stomach, proximal duodenum, pancreas) and tumors secondary to achlorhydria

- Midgut carcinoid tumors: Derived from the second portion of the duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, and the right colon

- Hindgut carcinoid tumors: Includes the transverse colon, descending colon, and rectum

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Carcinoid tumors are divided into well-differentiated (i.e., low grade [ENETS G1] and intermediate grade [ENETS G2]) and poorly differentiated (i.e., high grade [ENETS G3]). Classification based on the extent of the tumor are local, regional and distant spread. (See grading and staging)

Diagnosis

The etiology of carcinoid tumors is not known, but genetic abnormalities are suspected. Reported chromosomal abnormalities include changes in chromosomes, [18, 19] such as loss of heterogeneity, and numerical imbalances. The diagnosis is sometimes made because of unrelated findings, such as anemia, endocrine disease, or autoimmune disorders.

Laboratory testing

Laboratory diagnosis of carcinoid tumors depends on the identification of the characteristic biomarkers of the disease. [20, 21, 22] Measurement of biogenic amine levels (eg, serotonin, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid [5-HIAA], chromographin-A, catecholamines, histamine) and its metabolites in the platelets, plasma, and urine of patients can be helpful in making the diagnosis.

Imaging studies

Depending on the location of the tumor and metastasis, a combination of the following imaging modalities may be used to evaluate suspected carcinoid tumors:

- Plain radiography

- Upper and lower GI radiography with oral contrast agents

- Computed tomography scanning

- Magnetic resonance imaging

- Angiography

- Ultrasound including endoscopic ultrasound

- Positron emission tomography scanning

- Scintigraphy with metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) and octreotide [23, 24]

- Radionuclide imaging with somatostatin analogs attached to the radioactive tracer

- Technetium-99m bone scanning

Procedures

Endoscopic procedures, such as the following, may be used for biopsy and diagnosis:

- Bronchoscopy

- Esophagogastroscopy

- Gastroscopy

- Colonoscopy

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Surgery

If feasible, the treatment of choice for carcinoid tumors is surgical excision. The surgical technique may vary according to the type or location of the tumor. When total resection is not possible, debulking may provide symptomatic relief. In selected cases, cryotherapy can be effective.

Chemotherapy

If metastasis of carcinoid tumor has occurred and in cases where surgical excision is not suitable, consider treatment with currently recommended chemotherapeutic agents, individually or in combination, such as the following:

- Alkylating agents

- Doxorubicin

- 5-Fluorouracil

- Dacarbazine

- Actinomycin D

- Cisplatin

- Etoposide

- Streptozotocin

- Interferon alfa

- Somatostatin analogs with a radioactive load

- Experimental agents such as 177Lu-Dotatate [25]

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

Origin and general involvement and presentation

Carcinoid tumors are derived from primitive stem cells in the gut wall but can be seen in other organs, [5] including the lungs, [6] mediastinum, thymus, [7] liver, pancreas, bronchus, ovaries, [12] prostate, [13] and kidneys. [26] In children, most tumors occur in the appendix and are benign and asymptomatic. While very rare in children, bronchial carcinoid tumors are the most common primary pulmonary neoplasm in the pediatric age group. [9]

Most carcinoid tumors are slow growing and indolent without symptoms. Nevertheless, aggressive and metastatic disease (eg, to the brain) does occur. Even tumors in the appendix can metastasize. [27, 28] Depending on the size and location, carcinoid tumors can cause various symptoms, including carcinoid syndrome. [17] Carcinoid tumors of the ileum and jejunum, especially those larger than 1 cm, especially in adults, are most prone to produce this syndrome.

Classification

Carcinoid tumors generally are classified based on the location in the primitive gut (ie, foregut, midgut, hindgut) that gives rise to the tumor.

Foregut carcinoid tumors are divided into sporadic primary tumors and tumors secondary to achlorhydria. The term sporadic primary foregut tumor encompasses carcinoids of the lung, bronchus, stomach, proximal duodenum, and pancreas.

Midgut tumors are derived from the second portion of the duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, and the right colon. The image below shows the distribution of carcinoid tumors in adults.

Distribution of carcinoid tumors.

These account for 60-80% of all carcinoid tumors (especially those of the appendix and distal ileum) in adults and are also seen in children. [29] Appendicular carcinoid tumors are most common. [30, 31] In children, more than 70% of these tumors occur at the tip of the appendix and are often an incidental finding in appendectomy specimens. In one study, carcinoid tumors were found in 0.169% of 4747 appendectomies. [32] Overall, based on retroactive studies, up to 0.35% of children undergoing appendectomy have appendiceal carcinoid tumors. [14, 33] Bulky tumors are relatively rare and require somewhat extensive cecectomy or, when tumor infiltration is beyond the cecum, ileocecal resection. [34, 35, 31]

Hindgut carcinoid tumors include those of the transverse colon, descending colon, and rectum.

Carcinoid tumors can also arise from the Meckel diverticulum, cystic duplications, and the mesentery. Each of these entities has distinctive clinical, histochemical, and secretory features. For example, foregut carcinoids are argentaffin negative and have low serotonin content but secrete 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), histamine, and several polypeptide hormones. These tumors can metastasize to bone and may be associated with atypical carcinoid syndrome, acromegaly, Cushing disease, other endocrine disorders, telangiectasia, or hypertrophy of the skin in the face and upper neck.

Midgut carcinoids are argentaffin positive and can produce high levels of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), kinins, prostaglandins, substance P (SP), and other vasoactive peptides. These tumors have a rare potential to produce corticotropic hormone (previously adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]). Bone metastasis is uncommon.

Hindgut carcinoids are argentaffin negative and rarely secrete 5-HT, 5-HTP, or any other vasoactive peptides. Therefore, they do not produce related symptomatology. Bone metastases are not uncommon in these tumors.

Pathophysiology

Carcinoid tumors are of neuroendocrine origin and derived from primitive stem cells, which can give rise to multiple cell lineages. [36] In the intestinal tract, these tumors develop deep in the mucosa, growing slowly and extending into the underlying submucosa and mucosal surface. This results in the formation of small firm nodules, which bulge into the intestinal lumen. These tumors have a yellow, tan, or gray-brown appearance that can be observed through the intact mucosa. The yellow color is a result of cholesterol and lipid accumulation within the tumor. Tumors can have a polypoid appearance and occasionally become ulcerated. With expansion and infiltration through the submucosa into the muscularis propria and serosa, carcinoid tumors can involve the mesentery. Metastases to the mesenteric lymph node and liver, ovaries, peritoneum, and spleen can occur.

Upon histologic examination, carcinoid tumors have 5 distinctive patterns: (1) solid, nodular, and insular cords; (2) trabecular or ribbons with anastomosing features; (3) tubules and glands or rosettelike patterns; (4) poorly differentiated or atypical patterns; and (5) mixed patterns. A combination of these patterns is often observed. Tubules can contain mucinous secretions, and individual tumor cells can contain mucin-positive material, which includes the various acidic and neutral intestinal mucin. Tumors rarely have eosinophilic stroma. Capillaries are often prominent. Cells are uniformly round or polygonal with a central nucleus and punctate chromatin as well as small nucleoli and infrequent mitosis. The cytoplasm can be slightly acidophilic, basophilic, or amphophilic. Eosinophilic granules may be present. Immunohistochemically, these tumors have a strong positive reaction to keratin and neuroendocrine markers. These include chromogranin and synaptophysin.

In midgut carcinoids, cells are arranged in closely packed, round, regular, monomorphous masses. In the appendix, carcinoids appear as discrete yellow nodules in the lumen. Lesions associated with diffuse wall thickening are relatively uncommon. Carcinoid tumors commonly affect the tip of the appendix. Most carcinoid tumors invade the wall of the appendix, and lymphatic involvement is nearly universal. About 75% of patients have evidence of peritoneal involvement. However, only a few patients have regional or distant dissemination. The size of the tumor can be correlated with outcome of the disease; tumors smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter (after formalin fixation) rarely result in distant metastases or recurrences.

Carcinoid tumors can be associated with concentric and elastic vascular sclerosis that results in obliteration of vascular lumina and ischemia. A common finding is elastosis and fibrosis that surround nests of the tumor cells and that result in matting of the involved tissues and lymph nodes. Fibroblastic proliferation may result from the stimulation of fibroblast cells by growth factor. This stimulation may be as a result of a local release of tumor growth factor (TGF)-beta, beta–fibroblast growth factor (beta-FGF), and platelet-derived growth factor.

Other products of carcinoid tumors include the following:

- Acid phosphatase

- Alpha-1-antitrypsin

- Amylin

- Atrial natriuretic polypeptide

- Calbindin-D28k

- Catecholamines

- Dopamine

- Fibroblast growth factor

- Gastrin

- Gastrin-releasing peptide (bombesin)

- Glucagon, glicentin

- 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA)

- 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)

- Histamine

- Insulin

- Kallikrein

- Kinins

- Motilin

- Neuropeptide

- Neurotensin

- Pancreastatin

- Pancreatic polypeptide

- Platelet-dermal growth factor

- Prostaglandins

- Pyroglutamyl-glutamyl-prolinamide

- Secretin

- Serotonin

- Somatostatin (ie, SRIF)

- Tachykinins

- Neuropeptide K

- Neuropeptide A

- Substance P (SP)

- Transforming growth factor-beta

- Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)

Classic carcinoid tumor cells are argentaffinic and argyrophilic. At present, immunostain and hormonal markers are used for diagnosis. Carcinoid tumors of mediastinum can be misclassified as thymoma.

Carcinoids may have somatostatin receptors. Five identified somatostatin receptors are members of the G-protein receptor family. Five distinct genes on chromosomes 11, 14, 16, 17, and 20 encode somatostatin receptors. Somatostatin receptors are used to advantage for diagnosing and treating this disease.

Carcinoid tumors have high potential for metastasis. These cells produce a significant amount of beta-catenin, which enables the tumor cell adhesion, thus promoting metastasis. Induction of Raf1 results in decreased adhesion of carcinoid cells and may be important in the metastatic process. [37]

Etiology

The etiology of carcinoid tumors is not known, but genetic abnormalities, especially in pediatric pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, [9] are suspected. Reported chromosomal abnormalities include changes in chromosomes, such as loss of heterogeneity, and numerical imbalances.

- MEN 1 is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the occurrence of multiple tumors, particularly in the pancreatic islets, parathyroid and pituitary glands, and neuroendocrine tumors. [38]

- Germline mutations in the MEN 1 gene can be identified in the general population.

- Multiple carcinoid tumors occurring in association with MEN 1 have been reported. [39]

- Although the MEN 1 gene locus is known to be involved in neuroendocrine tumors, the genetic events underlying the neoplastic process are basically unknown.

- Familial cases other than those associated with MEN 1 are rare, but do occur. [40]

- In several studies, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the MEN 1 locus has been reported. [41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46]

- Genetic abnormalities involving chromosome 11 are most common. These can be seen as a part of MEN 1 or independent of MEN 1 abnormalities. [45, 46] In 5 of 9 typical carcinoid tumors of the lung, 3 distinct regions of allelic loss were identified at bands 11q13.1 (D11S1883), 11q14.3-11q21 (D11S906), and 11q25 (D11S910).

- Some atypical carcinoids have LOH at band 11q13 between markers PYGM and D11S937 and at bands 11q14.3-11q21 (D11S906), 11q23.2-23.3 (D11S939), and 11q25 (D11S910).

- The region of band 11q13 bearing the MEN 1 gene can also be affected in some atypical carcinoid tumors more than it is in typical carcinoid tumors. Therefore, band 11q13 appears to be important in these tumors. Aggressive atypical carcinoid tumors, defined by high mitosis, vascular invasion and organ metastasis, also appear to have more allelic losses than other tumors.

- The MEN 1 gene is located on band 11q13 and likely functions as a tumor-suppressor gene. In a study of 46 sporadically occurring tumors, 78% had LOH at this site, with almost the entire allele missing in 5 patients. In the remaining cases, genetic heterozygosity had a discontinuous pattern. Some have postulated that sporadically occurring carcinoid tumors evolve after inactivation of a tumor-suppressor gene on chromosome 11 as well as genetic mutations that affect DNA-mismatch repair.

- Gastric neuroendocrine tumors are associated with a high incidence of LOH at chromosomal arm 8p and a lowered frequency of LOH at 7q. Chromosomal arm 8p is suspected to be the possible location of the tumor-suppressor gene associated with the genesis of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. In one study, two out of five patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors had Von Hippel-Lindau disease and two others were diagnosed with multiple endocrine neoplasia type1. [47]

- LOH on the X chromosome is seen in 15% of malignant carcinoid tumors. [43, 44]

- Numerical imbalances of chromosomes have been observed in carcinoid tumors.

- In one study of midgut carcinoids, numerical changes were found in 16 of the 18 tumors.

- The most common aberrations were losses of bands 18q22-qter (67%), 11q22-q23 (33%), and 16q21-qter (22%) with a gain of band 4p14-qter (22%). Rates of alterations were substantially more common in metastases than in primary tumors.

- Losses of chromosomal arms 18q and 11q were found in the primary tumors and metastases, whereas loss of 16q and gain of 4p were present only in metastases.

- HER2 expression has been reported in intestinal, but not gastric, tumors. [48]

- Some studies have implicated homeobox gene Hoxc6 through activation of the oncogenic activator protein-1 signaling pathway and via interaction with JunD in carcinoid tumorigenesis. [49] Mutation in the home domain of Hoxc6, which blocks this interaction, results in inhibition of the carcinoid tumor cell proliferation in vitro.

- One postulate is that loss of chromosomal arms 18q and 11q may represent an early event and that the loss of 16q and gain of 4p occur as a late event in midgut carcinoids.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Carcinoids are the most common neuroendocrine tumors, with an estimated 1.5-1.9 clinical cases per 100,000 population. The incidence in autopsy cases is higher at 650 cases per 100,000 population. An estimated 8000 gastrointestinal (GI) tract–related carcinoid tumors are diagnosed each year in the United States. [50] A study by Zeineddin et al found that the prevalence of neuroendocrine tumors was 1:271 among children undergoing appendectomy for acute appendicitis. [51]

Evidence in adults suggests that overall incidence of carcinoid tumors has been steadily increasing. [52, 53] While not entirely clear, it is speculated that this increase is due to more universal utilization of proton pump inhibitors. The exact incidence in children is not known. Most tumors occur in adults and are rare in children.

Historically, prior to availability of improved diagnostic techniques, distant metastasis was reported in 12.9% range. A retrospective cohort study by Kasumova et al reported that out of 10,752 patients, 12.7% were diagnosed with carcinoid tumors, 84.7% with nonfunctional and 2.6% with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The incidence of carcinoid tumors rose from 36 (5.7%) diagnosed in 2004 to 497 (27.7%) in 2013. Overall survival was significantly longer for carcinoid compared with functional and nonfunctional tumors, with 5-year survival rates of 63.1%, 58.3%, and 52.6%, respectively. Overall survival for patients having resection improved significantly for carcinoid tumors (89.2%) compared to functional and non-functional tumors (76.6%, and 78.7%, respectively). [54]

International statistics

In 1980-1989, the overall age-standardized incidence rate for male and female populations in England were estimated to be 0.71 (0.68-0.75 and 0.87 (0.83-0.91), respectively. In Scotland, the respective rates were 1.17 (0.91-1.44) per 100,000 population and 1.36 (1.09-1.63) per 100,000 population. [55]

A study by Duess et al in Germany reported that appendiceal carcinoid tumors were found incidentally in 0.11% of children who underwent appendectomy (44 out of 40,499 patients). [56]

Prognosis

No systematic data for survival of children with carcinoid tumors is currently available.

The prognosis for patients with completely resected localized disease is excellent. [57, 58, 59, 60] Tumors larger than 2 cm, positive lymph nodes, and atypical histologic features are often associated with a poor prognosis. [61] In patients with carcinoid tumors located in the appendix, age, primary tumor size, histologic features, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis are significant factors in predicting survival. [62] In one retroactive study, survival of patients with sigmoid colon was only 33% while 99% of those with appendiceal tumor had survived. [58] Second primary malignancies of gastrointestinal tract which occurred in up to 33% of cases in adults,are unusual in children and adolescents. [59]

In adult patients, factors associated with poor survival include persistence of plasma neurokinin A (NKA), urinary 50-hydroxyindolacetic acid output, age, and 5 or more liver metastases. Rise in plasma NKA appears to be independent of other prognostic factors and constitutes the strongest indication. [63]

Overall, localized carcinoid tumor which is completely resected has an excellent prognosis; the outcome for patients with metastasis, however, remains poor.

Complications

The most serious complications of carcinoid tumors are carcinoid syndrome/crisis and metastasis, which is often observed in patients who have foregut tumors and high levels of 5-HIAA. [17]

- Ominoe G, Kodish E, Herman R. Neuroendocrine tumors of the appendix in adolescents and young adults. Clinics in Oncology. 2017 July. 2:1318.

- Kim SS, Kays DW, Larson SD, Islam S. Appendiceal carcinoids in children--management and outcomes. J Surg Res. 2014 Dec. 192 (2):250-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- de Lambert G, Lardy H, Martelli H, Orbach D, Gauthier F, Guérin F. Surgical Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Appendix in Children and Adolescents: A Retrospective French Multicenter Study of 114 Cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016 Apr. 63 (4):598-603. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Scott A, Upadhyay V. Carcinoid tumours of the appendix in children in Auckland, New Zealand: 1965-2008. N Z Med J. 2011 Mar 25. 124 (1331):56-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Broaddus RR, Herzog CE, Hicks MJ. Neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid and neuroendocrine carcinoma) presenting at extra-appendiceal sites in childhood and adolescence. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003 Sep. 127(9):1200-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moraes TJ, Langer JC, Forte V, et al. Pediatric pulmonary carcinoid: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003 Apr. 35(4):318-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Soga J, Yakuwa Y, Osaka M. Evaluation of 342 cases of mediastinal/thymic carcinoids collected from literature: a comparative study between typical carcinoids and atypical varieties. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999 Oct. 5(5):285-92. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhan J, Bao G, Hu X, Gao W, Ruo X, Gong J, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the common bile duct in children: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2010 Oct. 45 (10):2061-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kelemen D, Horváth OP, Juhász Z, Vajda P, Pintér A. Pancreatic carcinoid in childhood. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009 Aug. 19 (4):268-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Avanzini S, Pio L, Buffa P, Panigada S, Sacco O, Pini-Prato A, et al. Intraoperative bronchoscopy for bronchial carcinoid parenchymal-sparing resection: a pediatric case report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012 Jan. 28 (1):75-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Andersen JB, Mortensen J, Damgaard K, Skov M, Sparup J, Petersen BL, et al. Fourteen-year-old girl with endobronchial carcinoid tumour presenting with asthma and lobar emphysema. Clin Respir J. 2010 Apr. 4 (2):120-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Piura B, Dgani R, Zalel Y, et al. Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary: a study of 20 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1995 Jul. 59(3):155-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Murali R, Kneale K, Lalak N, Delprado W. Carcinoid tumors of the urinary tract and prostate. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006 Nov. 130(11):1693-706. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vandevelde A, Gera P. Carcinoid tumours of the appendix in children having appendicectomies at Princess Margaret Hospital since 1995. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Sep. 50 (9):1595-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Knigge U, Capdevila J, Bartsch DK, et al. ENETS Consensus Recommendations for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Follow-Up and Documentation. Neuroendocrinology. 2017. 105 (3):310-319. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Uskul BT, Turker H, Dincer IS, Melikoglu A, Tasolar O, Tahaoglu C. A primary tracheal carcinoid tumor masquerading as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. South Med J. 2008 May. 101(5):546-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Granata C, Haupt R, Mazzaferro V, Fratino G, Mattioli G, Gasparini M, et al. Carcinoid syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 1996 Jun. 11 (5-6):398-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jakobovitz O, Nass D, DeMarco L, Barbosa AJ, Simoni FB, Rechavi G, et al. Carcinoid tumors frequently display genetic abnormalities involving chromosome 11. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 Sep. 81 (9):3164-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zhao J, de Krijger RR, Meier D, Speel EJ, Saremaslani P, Muletta-Feurer S, et al. Genomic alterations in well-differentiated gastrointestinal and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoids): marked differences indicating diversity in molecular pathogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2000 Nov. 157 (5):1431-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cunningham JL, Janson ET. The biological hallmarks of ileal carcinoids. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011 Dec. 41 (12):1353-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Maroun J, Kocha W, Kvols L, Bjarnason G, Chen E, Germond C, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of carcinoid tumours. Part 1: the gastrointestinal tract. A statement from a Canadian National Carcinoid Expert Group. Curr Oncol. 2006 Apr. 13 (2):67-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Srivastava A, Hornick JL. Immunohistochemical staining for CDX-2, PDX-1, NESP-55, and TTF-1 can help distinguish gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors from pancreatic endocrine and pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009 Apr. 33 (4):626-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Monsieurs MA, Thierens HM, Vral A, et al. Patient dosimetry after 131I-MIBG therapy for neuroblastoma and carcinoid tumours. Nucl Med Commun. 2001 Apr. 22(4):367-74. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shi W, Johnston CF, Buchanan KD, et al. Localization of neuroendocrine tumours with [111In] DTPA-octreotide scintigraphy (Octreoscan): a comparative study with CT and MR imaging. QJM. 1998 Apr. 91(4):295-301. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. Phase 3 Trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for Midgut Neuroendocrine Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jan 12. 376 (2):125-135. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Romero FR, Rais-Bahrami S, Permpongkosol S, Fine SW, Kohanim S, Jarrett TW. Primary carcinoid tumors of the kidney. J Urol. 2006 Dec. 176(6 Pt 1):2359-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hlatky R, Suki D, Sawaya R. Carcinoid metastasis to the brain. Cancer. 2004 Dec 1. 101(11):2605-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Volpe A, Willert J, Ihnken K, et al. Metastatic appendiceal carcinoid tumor in a child. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000 Mar. 34(3):218-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schmittenbecher PP. Carcinoid tumours of the appendix in children--epidemiology, clinical aspects and procedures. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001 Dec. 11(6):428. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bethel CA, Bhattacharyya N, Hutchinson C, et al. Alimentary tract malignancies in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Jul. 32(7):1004-8; discussion 1008-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pelizzo G, La Riccia A, Bouvier R, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001 Jul. 17(5-6):399-402. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Doede T, Foss HD, Waldschmidt J. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children--epidemiology, clinical aspects and procedure. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000 Dec. 10(6):372-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fallon SC, Hicks MJ, Carpenter JL, Vasudevan SA, Nuchtern JG, Cass DL. Management of appendiceal carcinoid tumors in children. J Surg Res. 2015 Oct. 198 (2):384-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Soreide JA, van Heerden JA, Thompson GB, et al. Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors: long-term prognosis for surgically treated patients. World J Surg. 2000 Nov. 24(11):1431-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- D'Aleo C, Lazzareschi I, Ruggiero A, Riccardi R. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix in children: two case reports and review of the literature. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001 Jul-Aug. 18(5):347-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010 Aug. 39 (6):707-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Greenblatt DY, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. Raf-1 activation in gastrointestinal carcinoid cells decreases tumor cell adhesion. Am J Surg. 2007 Mar. 193(3):331-5; discussion 335. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Dreijerink KM, Roijers JF, van der Luijt RB, et al. [Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: recent developments and guidelines for DNA diagnosis and periodic clinical monitoring]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2000 Dec 16. 144(51):2445-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yazawa K, Kuroda T, Watanabe H, et al. Multiple carcinoids of the duodenum accompanied by type I familial multiple endocrine neoplasia. Surg Today. 1998. 28(6):636-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hemminki K, Li X. Familial carcinoid tumors and subsequent cancers: a nation-wide epidemiologic study from Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2001 Nov 1. 94(3):444-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vageli D, Danill Z, Dahabreh J. Microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity at the MEN1 locus in lung carcinoid tumors: a novel approach using real-time PCR with melting curve analysis in histopathologic material. Oncol Rep. 2006. 15:557-64.

- D'Adda T, Pizzi S, Azzoni C. Different patterns of 11q allelic losses in digestive endocrine tumors. Hum Pathol. 2002. 33:322-9.

- Pizzi S, D'Adda T, Azzoni c. Malignancy-associated allelic losses on the X-chromosome in foregut but not in midgut endocrine tumours. J Pathol. 2002. 196:401-7.

- Pizzi S, D'Adda T, Azzoni C, et al. Malignancy-associated allelic losses on the X-chromosome in foregut but not in midgut endocrine tumours. J Pathol. 2002 Apr. 196(4):401-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jakobovitz O, Nass D, DeMarco L. Carcinoid tumors frequently display genetic abnormalities involving chromosome 11. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996. 81:3164-7.

- Jakobovitz O, Nass D, DeMarco L, et al. Carcinoid tumors frequently display genetic abnormalities involving chromosome 11. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 Sep. 81(9):3164-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Diets IJ, Nagtegaal ID, Loeffen J, de Blaauw I, Waanders E, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. Childhood neuroendocrine tumours: a descriptive study revealing clues for genetic predisposition. Br J Cancer. 2017 Jan 17. 116 (2):163-168. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yamaguchi M, Hirose K, Hirai N. HER2 expression in gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors: high in intestinal but not in gastric tumors. Surg Today. 2007. 37(3):270-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fujiki K, Duerr EM, Kikuchi H, et al. Hoxc6 is overexpressed in gastrointestinal carcinoids and interacts with JunD to regulate tumor growth. Gastroenterology. 2008 Sep. 135(3):907-16, 916.e1-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics About Gastrointestinal Carcinoid Tumors. American Cancer Society. Available at https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/gastrointestinal-carcinoid-tumor/about/key-statistics.html. 2018 Sep 24; Accessed: February 29, 2024.

- Zeineddin S, Aldrink JH, Bering J, et al. Multi-institutional assessment of the prevalence of neuroendocrine tumors in children undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023 Nov. 70 (11):e30620. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Robertson RG, Geiger WJ, Davis NB. Carcinoid tumors. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Aug 1. 74(3):429-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ellis L, Shale MJ, Coleman MP. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: trends in incidence in England since 1971. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Dec. 105 (12):2563-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kasumova GG, Tabatabaie O, Eskander MF, Tadikonda A, Ng SC, Tseng JF. National Rise of Primary Pancreatic Carcinoid Tumors: Comparison to Functional and Nonfunctional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 2017 Jun. 224 (6):1057-1064. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Newton JN, Swerdlow AJ, dos Santos Silva IM, et al. The epidemiology of carcinoid tumours in England and Scotland. Br J Cancer. 1994 Nov. 70(5):939-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Duess JW, Lange A, Zeidler J, et al. Appendiceal Carcinoids in Children-Prevalence, Treatment and Outcome in a Large Nationwide Pediatric Cohort. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Dec 30. 59 (1):[QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Spunt SL, Pratt CB, Rao BN, et al. Childhood carcinoid tumors: the St Jude Children's Research Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2000 Sep. 35(9):1282-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Godwin JD 2nd. Carcinoid tumors. An analysis of 2,837 cases. Cancer. 1975 Aug. 36 (2):560-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fernández KS, Aldrink JH, Ranalli M, Ruymann FB, Caniano DA. Carcinoid tumors in children and adolescents: risk for second malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015 Mar. 37 (2):150-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Njere I, Smith LL, Thurairasa D, Malik R, Jeffrey I, Okoye B, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of appendiceal carcinoid tumors in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018 Aug. 65 (8):e27069. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003 Feb 15. 97 (4):934-59. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Landry CS, Woodall C, Scoggins CR, McMasters KM, Martin RC 2nd. Analysis of 900 appendiceal carcinoid tumors for a proposed predictive staging system. Arch Surg. 2008 Jul. 143(7):664-70; discussion 670. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Turner GB, Johnston BT, McCance DR, McGinty A, Watson RG, Patterson CC, et al. Circulating markers of prognosis and response to treatment in patients with midgut carcinoid tumours. Gut. 2006 Nov. 55(11):1586-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lal DR, Clark I, Shalkow J, et al. Primary epithelial lung malignancies in the pediatric population. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005 Oct 15. 45(5):683-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fink G, Krelbaum T, Yellin A, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature. Chest. 2001 Jun. 119(6):1647-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fauroux B, Aynie V, Larroquet M, et al. Carcinoid and mucoepidermoid bronchial tumours in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2005 Dec. 164(12):748-52. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tullie L, Vadgama B, Anbarasan R, Stanton MP, Steinbrecher H. The Excised Appendix Tip-To Send or not to Send, That is the Question. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2018 Jan. 6 (1):e81-e82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Barnó, PA, Rivilla, F, Yagüez, JB, et al. Appendiceal Carcinoid Tumor in Children: a Conservative Surgical Approach. Indian J Surgery. 2018 October. 80(5):461–464.

- Wu H, Chintagumpala M, Hicks J, Nuchtern JG, Okcu MF, Venkatramani R. Neuroendocrine Tumor of the Appendix in Children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017 Mar. 39 (2):97-102. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Anastasiadis K, Kepertis C, Lampropoulos V, Tsioulas P, Spyridakis I. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix - last decade experience. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Nov. 8 (11):NC01-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mathur A, Steffensen TS, Paidas CN, Ogera P, Kayton ML. The perforated appendiceal carcinoid in children: a surgical dilemma. J Pediatr Surg. 2012 Jun. 47 (6):1155-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Warrier RP, Varma AV, Chauhan A, Ward K, Craver R. Carcinoid tumor with bilateral renal involvement in a child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011 Dec. 33 (8):628-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wang WP, Guo C, Berney DM, et al. Primary carcinoid tumors of the testis: a clinicopathologic study of 29 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Apr. 34(4):519-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Atoui R, Almarzooqi S, Saleh W, Marcovitz S, Mulder D. Bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumor associated with Cushing syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008 Nov. 86(5):1688-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Capovilla M, Kambouchner M, Bernier M, Soulier A, Tissier F, Saintigny P. Late cerebellar relapse of a juvenile bronchial carcinoid. Clin Lung Cancer. 2007 Mar. 8(5):339-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Igaz P. MEN1 clinical background. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009. 668:1-15. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lin ZM, Chang YL, Lee CY, Wang CP, Hsiao TY. Simultaneous typical carcinoid tumour of larynx and occult papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2008 Jan. 122(1):93-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Aubry MC, Thomas CF Jr, Jett JR, Swensen SJ, Myers JL. Significance of multiple carcinoid tumors and tumorlets in surgical lung specimens: analysis of 28 patients. Chest. 2007 Jun. 131(6):1635-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Petrou A, Papalambros A, Papaconstantinou I, et al. Gastric carcinoid tumor in association with hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. South Med J. 2008 Nov. 101(11):1170-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moertel CG. Karnofsky memorial lecture. An odyssey in the land of small tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1987 Oct. 5(10):1502-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moertel CG. Treatment of the carcinoid tumor and the malignant carcinoid syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1983 Nov. 1(11):727-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Moertel CG, Weiland LH, Nagorney DM, Dockerty MB. Carcinoid tumor of the appendix: treatment and prognosis. N Engl J Med. 1987 Dec 31. 317(27):1699-701. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Delcore R, Friesen SR. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 1994 Feb. 178(2):187-211. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Mani S, Modlin IM, Ballantyne G, et al. Carcinoids of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1994 Aug. 179(2):231-48. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kulke MH, Mayer RJ. Carcinoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 18. 340(11):858-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Carling RS, Degg TJ, Allen KR, et al. Evaluation of whole blood serotonin and plasma and urine 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid in diagnosis of carcinoid disease. Ann Clin Biochem. 2002 Nov. 39(Pt 6):577-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saqi A, Alexis D, Remotti F, Bhagat G. Usefulness of CDX2 and TTF-1 in differentiating gastrointestinal from pulmonary carcinoids. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005 Mar. 123(3):394-404. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pattenden HA, Leung M, Beddow E, Dusmet M, Nicholson AG, Shackcloth M, et al. Test performance of PET-CT for mediastinal lymph node staging of pulmonary carcinoid tumours. Thorax. 2015 Apr. 70 (4):379-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Boggs W. PET-CT of Little Use in Mediastinal Lymph Node Staging of Pulmonary Carcinoid Tumors. Reuters Health Information. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/831316. September 09, 2014; Accessed: June 16, 2015.

- Kaltsas G, Korbonits M, Heintz E, et al. Comparison of somatostatin analog and meta-iodobenzylguanidine radionuclides in the diagnosis and localization of advanced neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Feb. 86(2):895-902. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Patel YC, Srikant CB. Subtype selectivity of peptide analogs for all five cloned human somatostatin receptors (hsstr 1-5). Endocrinology. 1994 Dec. 135 (6):2814-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Dubois S, Morel O, Rodien P, et al. A Pulmonary adrenocorticotropin-secreting carcinoid tumor localized by 6-Fluoro-[18F]L-dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission/computed tomography imaging in a patient with Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Dec. 92(12):4512-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Degnan AJ, Tadros SS, Tocchio S. Pediatric Neuroendocrine Carcinoid Tumors: Review of Diagnostic Imaging Findings and Recent Advances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017 Apr. 208 (4):868-877. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bloomston M, Al-Saif O, Klemanski D, et al. Hepatic artery chemoembolization in 122 patients with metastatic carcinoid tumor: lessons learned. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007 Mar. 11(3):264-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lefebvre S, De Paepe L, Abs R, et al. Subcutaneous octreotide treatment of a growth hormone-releasing hormone-secreting bronchial carcinoid: superiority of continuous versus intermittent administration to control hormonal secretion. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995 Sep. 133(3):320-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rubin J, Ajani J, Schirmer W, et al. Octreotide acetate long-acting formulation versus open-label subcutaneous octreotide acetate in malignant carcinoid syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Feb. 17(2):600-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Corleto VD, Angeletti S, Schillaci O, et al. Long-term octreotide treatment of metastatic carcinoid tumor. Ann Oncol. 2000 Apr. 11(4):491-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, Peeters M, Hörsch D, Winkler RE, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2011 Dec 10. 378(9808):2005-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pavel ME, Singh S, Strosberg JR, et al. Health-related quality of life for everolimus versus placebo in patients with advanced, non-functional, well-differentiated gastrointestinal or lung neuroendocrine tumours (RADIANT-4): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Oct. 18 (10):1411-1422. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Alvarez MC, Macias AA, Saurez MG, Fernandez ML, Lage DA. Bronchial carcinoid tumor treated with interferon and a new vaccine against NeuGcGM3 antigen expressed in malignant carcinoid cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007 Jun. 6(6):853-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Malkan AD, Wahid FN, Fernandez-Pineda I, Sandoval JA. Appendiceal carcinoid tumor in children: implications for less radical surgery?. Clin Transl Oncol. 2015 Mar. 17 (3):197-200. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Njere I, Smith LL, Thurairasa D, Malik R, Jeffrey I, Okoye B, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of appendiceal carcinoid tumors in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018 Aug. 65 (8):e27069. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kwaan MR, Goldberg JE, Bleday R. Rectal carcinoid tumors: review of results after endoscopic and surgical therapy. Arch Surg. 2008 May. 143(5):471-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Givi B, Pommier SJ, Thompson AK, Diggs BS, Pommier RF. Operative resection of primary carcinoid neoplasms in patients with liver metastases yields significantly better survival. Surgery. 2006 Dec. 140(6):891-7; discussion 897-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bertoletti L, Elleuch R, Kaczmarek D, Jean-Francois R, Vergnon JM. Bronchoscopic cryotherapy treatment of isolated endoluminal typical carcinoid tumor. Chest. 2006 Nov. 130(5):1405-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fornaro R, Frascio M, Sticchi C, et al. Appendectomy or right hemicolectomy in the treatment of appendiceal carcinoid tumors?. Tumori. 2007 Nov-Dec. 93(6):587-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bamboat ZM, Berger DL. Is right hemicolectomy for 2.0-cm appendiceal carcinoids justified?. Arch Surg. 2006 Apr. 141(4):349-52; discussion 352. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyons, France: IARC; 2010.

- Rindi G, Klöppel G, Alhman H, et al., European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS). TNM staging of foregut (neuro)endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2006 Oct. 449 (4):395-401. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Rindi G, Klöppel G, Couvelard A, Komminoth P, Körner M, Lopes JM, et al. TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2007 Oct. 451 (4):757-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004.

- [Guideline] Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, Filosso P, Garcia-Yuste M, Lim E, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015 Aug. 26 (8):1604-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Öberg K, Hellman P, Ferolla P, Papotti M, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct. 23 Suppl 7:vii120-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Neuroendocrine Tumors, Version 2.2016. NCCN. Available at https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/neuroendocrine.pdf. May 25, 2016; Accessed: October 2, 2016.

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

- [Guideline] Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020 Jul. 31 (7):844-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Berruti A, Baudin E, Gelderblom H, Haak HR, Porpiglia F, Fassnacht M, et al. Adrenal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct. 23 Suppl 7:vii131-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Ramage JK, Ahmed A, Ardill J, et al., UK and Ireland Neuroendocrine Tumour Society. Guidelines for the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine (including carcinoid) tumours (NETs). Gut. 2012 Jan. 61 (1):6-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, de Herder WW, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, et al. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010 Aug. 39 (6):735-52. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kunz PL, Reidy-Lagunes D, Anthony LB, Bertino EM, Brendtro K, Chan JA, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2013 May. 42 (4):557-77. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Delle Fave G, O'Toole D, Sundin A, Taal B, Ferolla P, Ramage JK, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Gastroduodenal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016. 103 (2):119-24. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Ramage JK, De Herder WW, Delle Fave G, Ferolla P, Ferone D, Ito T, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016. 103 (2):139-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Niederle B, Pape UF, Costa F, Gross D, Kelestimur F, Knigge U, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Jejunum and Ileum. Neuroendocrinology. 2016. 103 (2):125-38. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Park HW, Byeon JS, Park YS, Yang DH, Yoon SM, Kim KJ, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Jul. 72 (1):143-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chapman WC, Debelak JP, Wright Pinson C, Washington MK, Atkinson JB, Venkatakrishnan A, et al. Hepatic cryoablation, but not radiofrequency ablation, results in lung inflammation. Ann Surg. 2000 May. 231 (5):752-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell DL, de Herder WW, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, et al. NANETS treatment guidelines: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach and pancreas. Pancreas. 2010 Aug. 39 (6):735-52. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Öberg K, Knigge U, Kwekkeboom D, Perren A, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine gastro-entero-pancreatic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct. 23 Suppl 7:vii124-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016. 103 (2):153-71. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Lenders JW, Duh QY, Eisenhofer G, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Grebe SK, Murad MH, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun. 99 (6):1915-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Chen H, Sippel RS, O'Dorisio MS, Vinik AI, Lloyd RV, Pacak K, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and medullary thyroid cancer. Pancreas. 2010 Aug. 39 (6):775-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Zeiger MA, Thompson GB, Duh QY, Hamrahian AH, Angelos P, Elaraj D, et al. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Association of Endocrine Surgeons medical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009 Jul-Aug. 15 Suppl 1:1-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Partelli S, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Chen J, Knigge U, Niederle B, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Standard of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumours: Surgery for Small Intestinal and Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2017. 105 (3):255-265. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Author

Cameron K Tebbi, MD Director, Children's Cancer Research Group Laboratories

Cameron K Tebbi, MD is a member of the following medical societies: International Society of Pediatric Oncology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Specialty Editor Board

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Timothy P Cripe, MD, PhD, FAAP Chief, Division of Hematology/Oncology/BMT, Gordon Teter Endowed Chair in Pediatric Cancer, Nationwide Children's Hospital; Professor of Pediatrics, Ohio State University College of Medicine

Timothy P Cripe, MD, PhD, FAAP is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for the Advancement of Science, American Association for Cancer Research, American Pediatric Society, American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy, American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Connective Tissue Oncology Society, Society for Pediatric Research, Children's Oncology Group

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Max J Coppes, MD, PhD, MBA Executive Vice President, Chief Medical and Academic Officer, Renown Heath

Max J Coppes, MD, PhD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Healthcare Executives, American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Kathleen M Sakamoto, MD, PhD Shelagh Galligan Professor, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine

Kathleen M Sakamoto, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for Cancer Research, American Society of Hematology, American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, International Society for Experimental Hematology, Society for Pediatric Research, Western Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.