Ingrian phonology (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Distribution of the Ingrian language by 2007 (shown in blue).

Ingrian is a nearly extinct Finnic language of Russia. The spoken language remains unstandardised, and as such statements below are about the four known dialects of Ingrian (Ala-Laukaa, Hevaha, Soikkola and Ylä-Laukaa) and in particular the two extant dialects (Ala-Laukaa and Soikkola).

The written forms are, if possible, based on the written language (referred to as kirjakeeli, "book language") introduced by the Ingrian linguist Väinö Junus [fi] in the late 1930s. Following 1937's mass repressions in the Soviet Union, the written language was abolished and ever since, Ingrian does not have a (standardised) written language.

The following chart shows the monophthongs present in the Ingrian language:

Ingrian vowel phonemes[1]

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | i /i/ | y /y/ | (ь /ɨ/) | u /u/ |

| Mid | e /e/ | ö /ø/ | o /o/ | |

| Open | ä /æ/ | a /ɑ/ |

- The vowel /ɨ/ is only present in some Russian loanwords, like rьbakka ("fisher"); this vowel has been replaced by /i/ in some idiolects.[1]

- All vowels can occur as both short (/æ e i ɨ ø y ɑ o u/) and long (/æː eː iː ɨː øː yː ɑː oː uː/). The long vowel /ɨː/ is extremely rare, occurring in borrowed words like rььžoi ("red-haired").

- The vowels /eː øː oː/ are usually realised as diphthongs ([ie̯ yø̯ uo̯]) in the southern varieties of the Ala-Laukaa dialect, as diphthongoids ([i̯eː y̯øː u̯oː]) in many transitional varieties, and as [iː yː uː] in the northernmost Soikkola subdialects.[1]

Besides the diphthongs that arise due to diphthongisation of the long mid vowels ([ie̯ yø̯ uo̯]), Ingrian has a wide range of phonemic diphthongs, present in both dialects:

| -i | -u | -i | -y | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a- | ai /ɑi̯/ | au /ɑu̯/ | ä- | äi /æi̯/ | äy /æy̯/ |

| i- | – | iu /iu̯/ | |||

| e- | ei /ei̯/ | eu /eu̯/ | |||

| o- | oi /oi̯/ | ou /ou̯/ | ö- | öi /øi̯/ | öy /øy̯/ |

| u- | ui /ui̯/ | – | y- | yi /yi̯/ | – |

Ingrian has only one falling phonemic diphthong, iä (/iæ̯/), which is only present in the personal pronouns miä ("I") and siä ("you", singular).

Phonemically, Ingrian vowels can be long (/Vː/) and short (/V/) in both dialects. Short vowels after short stressed syllables are realised as half-long:[1]

kana /ˈkɑnɑ/ [ˈkɑnɑˑ]

Vowel reduction is furthermore a common feature in both dialects. In the Soikkola dialect, vowel reduction is restricted to the vowels a and ä; These vowels are sometimes reduced to [ə] in quick speech:[1]

linna /ˈlinːɑ/ [ˈlinːə] ("city")

ilma /ˈilmɑ/ [ˈiɫmə] ("weather")

In Ala-Laukaa, this process is much more common and regular, but varies greatly by speaker.[1] In the northernmost varieties, reduction is similar to that of the Soikkola dialect. In the southernmost idiolects, the following features appear:[1]

- Long unstressed vowels are shortened to short vowels (/ɑː eː iː oː uː æː øː yː/ to [ɑ e i o u æ ø y] respectively).

- Unstressed vowel clusters /u.ɑ o.ɑ/ are reduced to [o], /y.æ ø.æ/ to [ø], and /i.ɑ i.æ/ to [e].

- Unstressed diphthongs generally keep their quality and length. Diphthongs ending in /i̯/ may sometimes lose this glide, although this may be a phonological feature.

- Short unstressed vowels following a short stressed syllable remain unreduced, and continue to be realised as halflong (/ɑ e i o u æ ø y/ to [ɑˑ eˑ iˑ oˑ uˑ æˑ øˑ yˑ]).

- Other short unstressed /i o u ø y/ are shortened to [ĭ ŏ ŭ ø̆ y̆], respectively.

- When at word-end, these shortened vowels are furthermore pronounced as voiceless: [ĭ̥ ŏ̥ ŭ̥ ø̥̆ y̥̆] respectively.[4]

- The voiceless word-final [ĭ̥] may surface as palatalisation of the preceding consonant instead.

- Other short unstressed /ɑ æ/ are shortened to a schwa ([ə]), and dropped (or, potentially, devoiced to [ə̥]) at word-end.

- Short unstressed /e/ at word-end is dropped, and is sometimes also reduced to a schwa in polysyllabic words, although this is not as frequent as the reduction of /ɑ/ and /æ/.

Although some vowels merge in the process of reduction, speakers do generally have the knowledge of the original (unreduced) vowel quality.

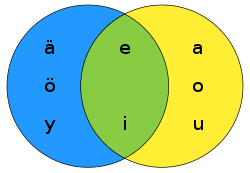

A diagram illustrating Ingrian vowel groups.

Ingrian, just like its closest relatives Finnish and Karelian, has the concept of vowel harmony. The principle of this morphophonetic phenomenon is that vowels in a word consisting of one root are all either front or back. As such, no native words can have any of the vowels {a, o, u} together with any of the vowels {ä, ö, y}.[2][5]

To harmonise formed words, any suffix containing one of these six vowels have two separate forms: a front vowel form and a back vowel form. Compare the following two words, formed using the suffix -kas: liivakas ("sandy") from liiva ("sand") and iäkäs ("elderly") from ikä ("age").[2][5]

The vowels {e, i} are considered neutral and can co-occur with both types of vowels. However, stems with these vowels are always front vowel harmonic: kivekäs ("rocky") from kivi ("rock").[2]

Compound words don't have to abide by the rules of vowel harmony, since they consist of two stems: rantakivi ("coastal stone") from ranta ("coast") + kivi ("stone").[2]

The consonantal phonology of Ingrian varies greatly among dialects. For example, while Soikkola Ingrian misses the voiced-unvoiced distinction, it has a three-way consonant length distinction, missing in the Ala-Laukaa dialect.[1]

Consonant inventory of Soikkola

| Labial | Dental | Postalveolar/ Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p, b /p/ | t, d /t/ | k, g /k/ | |

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | [ŋ] | |

| Fricative | f /f/ | s, z /s/ | [x] | h /h/ |

| Lateral | l /l/ | |||

| Trill | r /r/ | |||

| Affricate | ts /t͡s/ | c /t͡ʃ/ | ||

| Approximant | v /ʋ/ | j /j/ |

- The velar nasal [ŋ] is a form of /n/ occurring before the plosive /k/ (written ⟨nk⟩).

- The velar fricative [x] is a (half-)long version of /h/ (written ⟨hh⟩).

- Common realisations of /s/ are [ʃ] (in most subdialects) and [s̠] (in some subdialects).[6]

- /t͡ʃ/ is most commonly realised as the palatalised [t͡ɕ]

- /t͡s/ may be realised as the consonant cluster [ts̠].

In the Soikkola dialect, consonants have a three-way distinction in length. Geminates can be either short (1.5 times the length of a short consonant) or long (twice the length of a short consonant):[4]

tapa /ˈtɑpɑ/ ("manner" NOM)

tappaa /ˈtɑpˑɑː/ ("he/she catches" also: "manner" PTV)

tappaa /ˈtɑpːɑː/ ("to kill")

A similar phenomenon can be observed in the related Estonian language.

A word with the underlying structure *(C)VCVCV(C) is geminated to (C)VCˑVːCV(C) in the Soikkola dialect:

omena /ˈomˑeːnɑ/ ("apple" NOM; respelled ommeena)

omenan /ˈomˑeːnɑn/ ("apple" GEN; respelled ommeenan)

orava /ˈorˑɑːʋɑ/ ("squirrel" NOM; respelled orraava)

This rule however does not apply to forms that are underlyingly tetrasyllabic:

omenaal (< *omenalla) /ˈomenɑːl/ ("apple" ADE)

omenaks (< *omenaksi) /ˈomenɑːks/ ("apple" TRANSL)

The Soikkola dialect also exhibits a phonetic three-way voicing distinction for plosives and the sibilant:

- Intervocalically, short (ungeminated) consonants, when followed by a short vowel, are generally realised as semi-voiced, so [b̥], [d̥], [ɡ̊] and [ʒ̊] for /p/, /t/, /k/ and /s/ respectively:[4][7]

poika /ˈpoi̯kɑ/, [ˈpoi̯ɡ̊ɑ]

poikaa /ˈpoi̯kɑː/, [ˈpoi̯kɑː] - When preceding a hiatus, word-final consonants are also semi-voiced. When not, voicing assimilation occurs, resulting in voiced consonants ([b], [d], [ɡ], [ʒ]) before voiced consonants and vowels, and voiceless consonants ([p], [t], [k], [ʃ]) before voiceless consonants:[4][7]

pojat /ˈpojɑt/, [ˈpojɑd̥]

pojat nooret /ˈpojɑt ˈnoːret/, [ˈpojɑd‿ˈnoːred̥]

pojat suuret /ˈpojɑt ˈsuːret/, [ˈpojɑt‿ˈʃuːred̥]

pojat ovat /ˈpojɑt ˈoʋɑt/, [ˈpojɑd‿ˈoʋɑd̥] - Word-initially, plosives and sibilants are generally voiceless. Some speakers, however, may pronounce Russian loanwords, deriving from Russian words with a word-initial voiced plosive, with a voiced initial consonant:[4]

bocka [ˈpot͡ɕkɑ] ~ [ˈbot͡ɕkɑ]; compare also pocka [ˈpot͡ɕkɑ]

A word-final dental nasal (/n/) assimilates to the following stop and nasal:[7]

meehen poika [ˈmeːhem‿ˈpoi̯ɡ̊ɑ]

meehen koira [ˈmeːheŋ‿ˈkoi̯rɑ]

kanan muna [ˈkɑnɑm‿ˈmunɑ]

Some speakers also assimilate word-final /n/ to a following liquid, glottal fricative or bilabial approximant:[7]

meehen laps [ˈmeːhel‿lɑps]

joen ranta [ˈjoer‿rɑnd̥a]

miul on vene [ˈmiul oʋ‿ˈʋene]

varis on harmaa [ˈʋɑriz ox‿ˈxɑrmɑː]

Consonant inventory of Ala-Laukaa | | Labial | Dental | Postalveolar/ Palatal | Velar | Glottal | | | | | -------------------------------------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- | | | Plosive | p /p/ | b /b/ | t /t/ | d /d/ | k /k/ | g /ɡ/ | | | Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | | /ŋ/ | | | | | Fricative | f /f/ | s /s/ | z /z/ | š /ʃ/ | ž /ʒ/ | h /h/ | | | Lateral | l /l/ | | | | | | | | Trill | r /r/ | | | | | | | | Affricate | ts /t͡s/ | c /t͡ʃ/ | | | | | | | Approximant | v /ʋ/ | | j /j/ | | | | |

- The velar nasal /ŋ/ only appears before the plosive /k/ (written ⟨nk⟩) or /ɡ/ (written ⟨ng⟩)

- /t͡s/ may be realised as the consonant cluster [ts].

- /t͡s/ sometimes corresponds to Soikkola /t͡ʃ/ and is thus written ⟨c⟩: compare mancikka (Soikkola [ˈmɑnt͡ʃikːɑ], Ala-Laukaa [ˈmɑnt͡sikːə̥]).

In the Ala-Laukaa dialect, phonetic palatalisation of consonants in native words occurs first of all before the vowels {y, i} and the approximant /j/:[1]

tyttö [ˈtʲytːø̥̆] ("girl"); compare Soikkola [ˈtytːøi̯] and Standard Finnish [ˈt̪yt̪ːø̞].

The palatalised /t/ and /k/ may both be realised as [c] by some speakers. Furthermore, palatalisation before /y(ː)/ and /i(ː)/ that have developed from an earlier */ø/ or */e/ respectively is rare:

töö [ˈtøː] ~ [ˈtyø̯] ~ [ˈtyː] ("you (plural)")

The cluster ⟨lj⟩ is realised as a long palatalised consonant in the Ala-Laukaa dialect:[7]

neljä [ˈnelʲː(ə̥)] ("four"); compare Soikkola [ˈneljæ]

paljo [ˈpɑlʲːŏ̥] ("many"); compare Soikkola [ˈpɑljo]

kiljua [ˈkilʲːo] ("to shout"); compare Standard Finnish [ˈkiljuɑ]

These same phenomena are noticed in the extinct Ylä-Laukaa dialect:[7]

tyttö [ˈtʲytːøi̯] ("girl")

neljä [ˈnelʲːæ] ("four")

At the end of a word, the sibilant ⟨s⟩ and the stop ⟨t⟩ are voiced:

lammas [ˈlɑmːəz] ("sheep")

linnut [ˈlinːŭd] ("birds")

Like in the Soikkola dialect, when preceding a word beginning with a voiceless stop, this sibilant is again devoiced:

lammas pellool [ˈlɑmːəs‿ˈpelolː(ə̥)]

linnut kyläs [ˈlinːŭt‿ˈkylæsː(ə̥)]

Stress in Ingrian falls on the first syllable in native words, but may be shifted in loanwords. An exception is the word paraikaa (/pɑrˈɑi̯kɑː/, "now"), where the stress falls on the second syllable. Secondary stress falls on odd-numbered syllables or occurs as a result of compounding and is not phonemic.[1][5]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j N. V. Kuznetsova (2009). Фонологические системы Ижорских диалектов [_The phonological systems of the Ingrian dialects_]. Institute for Linguistic Studies (dissertation).

- ^ a b c d e V. I. Junus (1936). Iƶoran Keelen Grammatikka [_The grammar of the Ingrian language_]. Riikin Ucebno-pedagogiceskoi Izdateljstva.

- ^ A. Laanest (1966). "Ижорский Язык". Финно-Угорские и Самодийские языки. Языки народов мира. pp. 102–117.

- ^ a b c d e N. V. Kuznetsova (2015). "Две фонологические редкости Ижорского языка" [Two phonological rarities of the Ingrian language]. Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. XI (2).

- ^ a b c O. I. Konkova; N. A. D'jachinkov (2014). Inkeroin Keel: Пособие по Ижорскому Языку. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography .

- ^ F. I. Rozhanskij (2010). "Ижорский язык: Проблема определения границ в условиях языкового континуума". Вопросы языкознания: 74–93. ISSN 0373-658X.

- ^ a b c d e f R. E. Nirvi (1971). Inkeroismurteiden sanakirja [_Dictionary of the Ingrian dialects_].