Jitterbug (original) (raw)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dance style associated with swing dance

Jitterbug

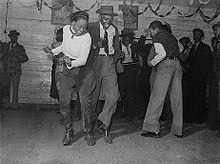

Jitterbugging at a juke joint, 1939. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott Jitterbugging at a juke joint, 1939. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott |

|

|---|---|

| Genre | Swing |

Jitterbug is a generalized term used to describe swing dancing.[1] It is often synonymous with the lindy hop dance[2][3] but might include elements of the jive, east coast swing, collegiate shag, charleston, balboa and other swing dances.[4]

Swing dancing originated in the African-American communities of New York City in the early 20th century.[5] Many nightclubs had a whites-only or blacks-only policy due to racial segregation, however the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem had a no-discrimination policy which allowed whites and blacks to dance together[6] and it was there that the Lindy Hop dance flourished,[7] started by dancers such as George Snowden and Frank Manning. The term jitterbug was originally a ridicule used by black patrons to describe whites who started to dance the Lindy Hop, as they were dancing faster and jumpier than was intended, like "jittering bugs",[8] although it quickly lost its negative connotation as the more erratic version caught on. Both the Lindy Hop and the "jitterbug" became popular outside Harlem when the dance was featured in Hollywood films and Broadway theatre, starring the performance group Whitey's Lindy Hoppers.

Dancing the jitterbug, Los Angeles, 1939

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) the word "jitterbug" is a combination of the words "jitter" and "bug";[9][10] both words are of unknown origin.[11][12][13]

The first use of the word "jitters" quoted by the OED is from 1929, Act II of the play Strictly Dishonorable by Preston Sturges where the character Isabelle says: "Willie's got the jitters" is answered by a judge "Jitters?" to which Isabelle answers "You know, he makes faces all the time."[11][14] The second quote in the OED is from the N.Y. Press from 2 April 1930: "The game is played only after the mugs and wenches have taken on too much gin and they arrive at the state of jitters, a disease known among the common herd as heebie jeebies."[11][15]

The first quote containing the term “jitter bug” recorded by the OED is from the 1934 Cab Calloway song “Jitter Bug”. The magazine Song Hits, in the 19 November 1939 issue, published the lyrics, including: “They’re four little jitter bugs. He has the jitters ev’ry morn; that’s why jitter sauce was born.”[9]

According to H. W. Fry in his review of Dictionary of Word Origins by Joseph Twadell Shipley in 1945 the word "jitters" "is from a spoonerism ['bin and jitters' for 'gin and bitters']...and originally referred to one under the influence of gin and bitters".[14]

Wentworth and Flexner explains "jitterbug" as "[o]ne who, though not a musician, enthusiastically likes or understands swing music; a swing fan" or "[o]ne who dances frequently to swing music" or "[a] devotee of jitterbug music and dancing; one who follows the fashions and fads of the jitterbug devotee... To dance, esp[ecially] to jazz or swing music and usu[ally] in an extremely vigorous and athletic manner".[14]

Jitterbug dancers in 1938

Jitterbugging developed from dances performed by African-Americans at juke joints and dance halls.[16] The Carolina shag and single Lindy Hop dances formed the basis of the jitterbug, which gave way to the double Lindy Hop when rock and roll became popular.[17]

White dancers picked up the energetic jitterbug from dancers at black venues. Venues in the Hill District of Pittsburgh were popular places for whites to learn the jitterbug.[18] The Savoy Ballroom, a dance hall in Harlem, was a famous cross-cultural venue, frequented by both black locals and white tourists.[16] Norma Miller, a former Lindy Hop dancer who regularly performed at the Savoy, noted that the dances performed there were choreographed in advance, which was not always understood by the tourists, who sometimes believed the performers were just dancing socially.[19]

A musical number called "The Jitterbug" was written for the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. The "jitterbug" was a bug sent by the Wicked Witch of the West to waylay the heroes by forcing them to do a jitterbug-style dance.[_citation needed_] Although the sequence was not included in the final version of the film, the witch is later heard to tell the flying monkey leader, "I've sent a little insect on ahead to take the fight out of them." The song as sung by Judy Garland as Dorothy and some of the establishing dialogue survived from the soundtrack as the B-side of the disc release of "Over the Rainbow".[_citation needed_]

Jitterbug dancing competition, Trocadero, Sydney, 1948

Jitterbug dancers, Trocadero, Sydney, 1948

In 1944, with the United States' continuing involvement in World War II, a 30% federal excise tax was levied against night clubs that featured dancing. Although the tax was later reduced to 20%, "No Dancing Allowed" signs went up all over the country. It has been argued that this tax had a significant role in the decline of public dancing as a recreational activity in the United States.[20][21][22]

World War II facilitated the spread of jitterbug across the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans. Across the Atlantic in preparation for D-Day, there were nearly 1,6 million American troops stationed throughout Britain in May 1944. Numbers dwindled thereafter, but as late as April 30, 1945 there were still over 224,000 airmen, 109,000 communications zone troops, and 100,000 in hospitals or preparing to serve as individual replacements.[_citation needed_]

Dancing was not a popular pastime in Britain before the war, and many ballrooms had been closed for lack of business. In the wake of the arrival of American troops, many of these re-opened, installing jukeboxes rather than hiring live bands. Working class women who had never danced recreationally before made up a large part of the attendees, along with American soldiers and sailors.[23] British Samoans were doing a "Seabee version" of the jitterbug by January 1944.[24] By November 1945 after the departure of the American troops following D-Day, English couples were being warned not to continue doing energetic "rude American dancing," as it was disapproved of by the upper classes.[23] Time reported that American troops stationed in France in 1945 jitterbugged,[25] and by 1946, jitterbug had become a craze in England.[26] It was already a competition dance in Australia.[27]

A United Press item datelined Hollywood on 9 June 1945 stated that dancer Florida Edwards was awarded a $7,870 judgement by the district court of appeals for injuries she sustained while jitterbugging at the Hollywood Canteen the previous year.[28][29]

In 1957, the Philadelphia-based television show American Bandstand was picked up by the American Broadcasting Company and shown across the United States. American Bandstand featured popular songs of the day, live appearances by musicians, and dancing in the studio. At this time, the most popular fast dance was jitterbug, which was described as "a frenetic leftover of the swing era ballroom days that was only slightly less acrobatic than Lindy".[30]

In a 1962 article in the Memphis Commercial Appeal, bassist Bill Black, who had backed Elvis Presley from 1954 to 1957, listed "jitterbug" along with the twist and cha-cha as "the only dance numbers you can play".[31]

- ^ "Jitterbug".

- ^ "The Call of the Jitterbug".

- ^ Manning, Frankie; Cynthia R. Millman (2007). Frankie Manning: Ambassador of Lindy Hop. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-59213-563-9.

- ^ "Jitterbug".

- ^ "Jitterbug".

- ^ "Jitterbug".

- ^ "The Call of the Jitterbug".

- ^ "Jitterbug and Lindy Hop".

- ^ a b "jitterbug, n. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "jitterbug, v. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b c "jitter, n. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "jitter, v.. in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "bug, n.2 in Oxford English Dictionary". Subscription service. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 November 2014. Etymology unknown. Usually supposed to be a transferred sense of BUG n.1; but this is merely a conjecture, without actual evidence, and it has not been shown how a word meaning 'object of terror, bogle', became a generic name for beetles, grubs, etc. Sense 1 shows either connection or confusion with the earlier budde ; in quot. 1783 at sense 1 shorn bug appears for Middle English scearn-budde (-bude) < Old English scearn-budda dung beetle, and in Kent the 'stag-beetle' is still called shawn-bug. Compare Cheshire 'buggin, a louse' (Holland).

- ^ a b c Wentworth, Harold and Stuart Berg Flexner, ed. (1975). Dictionary of American Slang (2nd ed.). New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company. p. 293. ISBN 0690006705. 1945: "[The term] is from a Spoonerism ['bin and jitters' for 'gin and bitters'] ... and originally referred to one under the influence of gin and bitters" H. W. Fry, rev. of J. T. Shipley's Dict. of Word Origins, Phila. Bulletin, Oct. 16. B22.

- ^ According to The Oxford English Dictionary heebie-jeebie means "A feeling of discomfort, apprehension, or depression; the 'jitters'; delirium tremens; also, formerly, a type of dance."

- ^ a b Stearns, Marshall and Jean (1968). Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Macmillan. page 331. ISBN 0-02-872510-7

- ^ Dance a While: Handbook of Folk, Square, and Social Dancing. Fourth Edition. Harris, Pittman, Waller. 1950, 1955, 1964, 1968. Burgess Publishing Company. No ISBN or catalog number. page 284.

- ^ Stearns, Marshall and Jean (1968). Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Macmillan. page 330. ISBN 0-02-872510-7

- ^ Swinging at the Savoy. Norma Miller. page 63.

- ^ Felten, Eric (17 March 2013). "How the Taxman Cleared the Dance Floor". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ COPELAND, JOHN (1945). "Some Effects of the Changes in the Federal Cabaret Tax in 1944". Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Taxation Under the Auspices of the National Tax Association. 38: 321–339. ISSN 2329-9045. JSTOR 23404801.

- ^ Hill, Constance Valis (2010). Tap dancing America : a cultural history. Internet Archive. New York, N.Y. : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539082-7.

- ^ a b Billboard, 24 November 1945. "Britons Drive to End Jiving as Yanks Go Home". page 88

- ^ Popular Science, January 1944. "The Seabees Can Do It". page 57.

- ^ "U.S. At War: G.I. Heaven". Time. 18 June 1945. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007.

- ^ Clarke, Mary; Crisp, Clement (1981). The History of Dance. Orbis. ISBN 978-0-85613-270-4.

- ^ "Muscle beach party". Smh.com.au. 8 January 2009.

- ^ United Press, no headline, The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Sunday 10 June 1945, Volume 51, page 6.

- ^ "Edwards v. Hollywood Canteen". Justia Law. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Shore, Michael; Dick Clark (1985). The History of American Bandstand. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 54. ISBN 0-345-31722-X.

- ^ The Blue Moon Boys: The Story of Elvis Presley's Band. Ken Burke and Dan Griffin. 2006. Chicago Review Press. page 146. ISBN 1-55652-614-8.