Method of analytic tableaux (original) (raw)

Tool for proving a logical formula

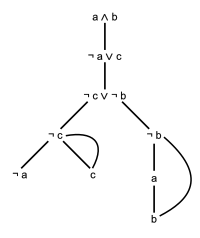

A graphical representation of a partially built propositional tableau

In proof theory, the semantic tableau[1] (; plural: tableaux), also called an analytic tableau,[2] truth tree,[1] or simply tree,[2] is a decision procedure for sentential and related logics, and a proof procedure for formulae of first-order logic.[1] An analytic tableau is a tree structure computed for a logical formula, having at each node a subformula of the original formula to be proved or refuted. Computation constructs this tree and uses it to prove or refute the whole formula.[3] The tableau method can also determine the satisfiability of finite sets of formulas of various logics. It is the most popular proof procedure for modal logics.[4]

A method of truth trees contains a fixed set of rules for producing trees from a given logical formula, or set of logical formulas. Those trees will have more formulas at each branch, and in some cases, a branch can come to contain both a formula and its negation, which is to say, a contradiction. In that case, the branch is said to close.[1] If every branch in a tree closes, the tree itself is said to close. In virtue of the rules for construction of tableaux, a closed tree is a proof that the original formula, or set of formulas, used to construct it was itself self-contradictory,[1] and therefore false. Conversely, a tableau can also prove that a logical formula is tautologous: if a formula is tautologous, its negation is a contradiction, so a tableau built from its negation will close.[1]

In his Symbolic Logic Part II, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (also known by his literary pseudonym, Lewis Carroll) introduced the Method of Trees, the earliest modern use of a truth tree.[5]

The method of semantic tableaux was invented by the Dutch logician Evert Willem Beth (Beth 1955)[6] and simplified, for classical logic, by Raymond Smullyan (Smullyan 1968, 1995).[7] Smullyan's simplification, "one-sided tableaux", is described here. Smullyan's method has been generalized to arbitrary many-valued propositional and first-order logics by Walter Carnielli (Carnielli 1987).[8]

Tableaux can be intuitively seen as sequent systems upside-down. This symmetrical relation between tableaux and sequent systems was formally established in (Carnielli 1991).[9]

Propositional logic

[edit]

A formula in propositional logic consists of letters, which stand for propositions, and connectives for conjunction, disjunction, conditionals, biconditionals, and negation. The truth or falsehood of a proposition is called its truth value. A formula, or set of formulas, is said to be satisfiable if there is a possible assignment of truth-values to the propositional letters such that the entire formula, which combines the letters with connectives, is itself true as well.[1] Such an assignment is said to satisfy the formula.[2]

A tableau checks whether a given set of formulae is satisfiable or not. It can be used to check either validity or entailment: a formula is valid if its negation is unsatisfiable, and formulae A 1 , … , A n {\displaystyle A_{1},\ldots ,A_{n}}

The following table shows some notational variants for logical connectives, for readers who may be more familiar with a different notation from the one used here. In general, as of the time of the inclusion of this sentence, the first symbol in each line has been used in the text of this article; however, since Wikipedia editors are not rule-bound to use consistent notation within or between articles, this may change.

Notational variants of the connectives[10][11]

| Connective | Symbol |

|---|---|

| AND | A ∧ B {\displaystyle A\land B}  , A ⋅ B {\displaystyle A\cdot B} , A ⋅ B {\displaystyle A\cdot B}  , A B {\displaystyle AB} , A B {\displaystyle AB}  , A & B {\displaystyle A\&B} , A & B {\displaystyle A\&B}  , A & & B {\displaystyle A\&\&B} , A & & B {\displaystyle A\&\&B}  |

| equivalent | A ≡ B {\displaystyle A\equiv B}  , A ⇔ B {\displaystyle A\Leftrightarrow B} , A ⇔ B {\displaystyle A\Leftrightarrow B}  , A ⇋ B {\displaystyle A\leftrightharpoons B} , A ⇋ B {\displaystyle A\leftrightharpoons B}  |

| implies | A ⇒ B {\displaystyle A\Rightarrow B}  , A ⊃ B {\displaystyle A\supset B} , A ⊃ B {\displaystyle A\supset B}  , A → B {\displaystyle A\rightarrow B} , A → B {\displaystyle A\rightarrow B}  |

| NAND | A ∧ ¯ B {\displaystyle A{\overline {\land }}B}  , A ∣ B {\displaystyle A\mid B} , A ∣ B {\displaystyle A\mid B}  , A ⋅ B ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {A\cdot B}}} , A ⋅ B ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {A\cdot B}}}  |

| nonequivalent | A ≢ B {\displaystyle A\not \equiv B}  , A ⇎ B {\displaystyle A\not \Leftrightarrow B} , A ⇎ B {\displaystyle A\not \Leftrightarrow B}  , A ↮ B {\displaystyle A\nleftrightarrow B} , A ↮ B {\displaystyle A\nleftrightarrow B}  |

| NOR | A ∨ ¯ B {\displaystyle A{\overline {\lor }}B}  , A ↓ B {\displaystyle A\downarrow B} , A ↓ B {\displaystyle A\downarrow B}  , A + B ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {A+B}}} , A + B ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {A+B}}}  |

| NOT | ¬ A {\displaystyle \neg A}  , − A {\displaystyle -A} , − A {\displaystyle -A}  , A ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {A}}} , A ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {A}}}  , ∼ A {\displaystyle \sim A} , ∼ A {\displaystyle \sim A}  |

| OR | A ∨ B {\displaystyle A\lor B}  , A + B {\displaystyle A+B} , A + B {\displaystyle A+B}  , A ∣ B {\displaystyle A\mid B} , A ∣ B {\displaystyle A\mid B}  , A ∥ B {\displaystyle A\parallel B} , A ∥ B {\displaystyle A\parallel B}  |

| XNOR | A {\displaystyle A}  XNOR B {\displaystyle B} XNOR B {\displaystyle B}  |

| XOR | A ∨ _ B {\displaystyle A{\underline {\lor }}B}  , A ⊕ B {\displaystyle A\oplus B} , A ⊕ B {\displaystyle A\oplus B}  |

The main principle of propositional tableaux is to attempt to "break" complex formulae into smaller ones until complementary pairs of literals are produced or no further expansion is possible.

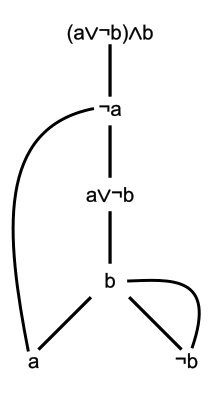

Initial tableau for {(a⋁¬b)⋀b,¬a}

The method works on a tree whose nodes are labeled with formulae. At each step, this tree is modified; in the propositional case, the only allowed changes are additions of a node as descendant of a leaf. The procedure starts by generating the tree made of a chain of all formulae in the set to prove unsatisfiability.[12] Then, the following procedure may be repeatedly applied nondeterministically:

- Pick an open leaf node. (The leaf node in the initial chain is marked open).

- Pick an applicable node on the branch above the selected node.[13]

- Apply the applicable node, which corresponds to expanding the tree below the selected leaf node based on some expansion rule (detailed below).

- For every newly created node that is both a literal/negated literal, and whose complement appears in a prior node on the same branch, mark the branch as closed. Mark all other newly created nodes as open.

Eventually, this procedure will terminate, because at some point every applicable node gets applied, and the expansion rules guarantee that every node in the tree is simpler than the applicable node used to create it.

The principle of tableau is that formulae in nodes of the same branch are considered in conjunction while the different branches are considered to be disjuncted. As a result, a tableau is a tree-like representation of a formula that is a disjunction of conjunctions. This formula is equivalent to the set to prove unsatisfiability. The procedure modifies the tableau in such a way that the formula represented by the resulting tableau is equivalent to the original one. One of these conjunctions may contain a pair of complementary literals, in which case that conjunction is proved to be unsatisfiable. If all conjunctions are proved unsatisfiable, the original set of formulae is unsatisfiable.

(a⋁¬b)⋀b generates a⋁¬b and b

Whenever a branch of a tableau contains a formula A ∧ B {\displaystyle A\wedge B}

( ∧ {\displaystyle \wedge }

) If a branch of the tableau contains a conjunctive formula A ∧ B {\displaystyle A\wedge B}

, add to its leaf the chain of two nodes containing the formulae A {\displaystyle A}

and B {\displaystyle B}

This rule is generally written as follows:

( ∧ ) A ∧ B A B {\displaystyle (\land ){\frac {A\wedge B}{\begin{array}{c}A\\B\end{array}}}}

A variant of this rule allows a node to contain a set of formulae rather than a single one. In this case, the formulae in this set are considered in conjunction, so one can add { A , B } {\displaystyle \{A,B\}}

a⋁¬b generates a and ¬b

If a branch of a tableau contains a formula that is a disjunction of two formulae, such as A ∨ B {\displaystyle A\vee B}

( ∨ {\displaystyle \vee }

) If a node on a branch contains a disjunctive formula A ∨ B {\displaystyle A\vee B}

, then create two sibling children to the leaf of the branch, containing the formulae A {\displaystyle A}

and B {\displaystyle B}

, respectively.

This rule splits a branch into two, differing only for the final node. Since branches are considered in disjunction to each other, the two resulting branches are equivalent to the original one, as the disjunction of their non-common nodes is precisely A ∨ B {\displaystyle A\vee B}

( ∨ ) A ∨ B A ∣ B {\displaystyle (\vee ){\frac {A\vee B}{A\mid B}}}

If nodes are assumed to contain sets of formulae, this rule is replaced by: if a node is labeled Y ∪ { A ∨ B } {\displaystyle Y\cup \{A\vee B\}}

The aim of tableaux is to generate progressively simpler formulae until pairs of opposite literals are produced or no other rule can be applied. Negation can be treated by initially making formulae in negation normal form, so that negation only occurs in front of literals. Alternatively, one can use De Morgan's laws during the expansion of the tableau, so that for example ¬ ( A ∧ B ) {\displaystyle \neg (A\wedge B)}

( ¬ 1 ) A ¬ ¬ A {\displaystyle (\neg 1){\frac {A}{\neg \neg A}}}

( ¬ 2 ) ¬ ¬ A A {\displaystyle (\neg 2){\frac {\neg \neg A}{A}}}

The tableau is closed

Every tableau can be considered as a graphical representation of a formula, which is equivalent to the set the tableau is built from. This formula is as follows: each branch of the tableau represents the conjunction of its formulae; the tableau represents the disjunction of its branches. The expansion rules transforms a tableau into one having an equivalent represented formula. Since the tableau is initialized as a single branch containing the formulae of the input set, all subsequent tableaux obtained from it represent formulae which are equivalent to that set (in the variant where the initial tableau is the single node labeled true, the formulae represented by tableaux are consequences of the original set.)

A tableau for the satisfiable set {a⋀c,¬a⋁b}: all rules have been applied to every formula on every branch, but the tableau is not closed (only the left branch is closed), as expected for satisfiable sets

The method of tableaux works by starting with the initial set of formulae and then adding to the tableau simpler and simpler formulae until contradiction is shown in the simple form of opposite literals. Since the formula represented by a tableau is the disjunction of the formulae represented by its branches, contradiction is obtained when every branch contains a pair of opposite literals.

Once a branch contains a literal and its negation, its corresponding formula is unsatisfiable. As a result, this branch can be now "closed", as there is no need to further expand it. If all branches of a tableau are closed, the formula represented by the tableau is unsatisfiable; therefore, the original set is unsatisfiable as well. Obtaining a tableau where all branches are closed is a way for proving the unsatisfiability of the original set. In the propositional case, one can also prove that satisfiability is proved by the impossibility of finding a closed tableau, provided that every expansion rule has been applied everywhere it could be applied. In particular, if a tableau contains some open (non-closed) branches and every formula that is not a literal has been used by a rule to generate a new node on every branch the formula is in, the set is satisfiable.

This rule takes into account that a formula may occur in more than one branch (this is the case if there is at least a branching point "below" the node). In this case, the rule for expanding the formula has to be applied so that its conclusion(s) are appended to all of these branches that are still open, before one can conclude that the tableau cannot be further expanded and that the formula is therefore satisfiable.

Set-labeled tableau

[edit]

A variant of tableau is to label nodes with sets of formulae rather than single formulae. In this case, the initial tableau is a single node labeled with the set to be proved satisfiable. The formulae in a set are therefore considered to be in conjunction.

The rules of expansion of the tableau can now work on the leaves of the tableau, ignoring all internal nodes. For conjunction, the rule is based on the equivalence of a set containing a conjunction A ∧ B {\displaystyle A\wedge B}

( ∧ ) X ∪ { A ∧ B } X ∪ { A , B } {\displaystyle (\wedge ){\frac {X\cup \{A\wedge B\}}{X\cup \{A,B\}}}}

For disjunction, a set X ∪ { A ∨ B } {\displaystyle X\cup \{A\vee B\}}

( ∨ ) X ∪ { A ∨ B } X ∪ { A } | X ∪ { B } {\displaystyle (\vee ){\frac {X\cup \{A\vee B\}}{X\cup \{A\}|X\cup \{B\}}}}

Finally, if a set contains both a literal and its negation, this branch can be closed:

( i d ) X ∪ { p , ¬ p } c l o s e d {\displaystyle (id){\frac {X\cup \{p,\neg p\}}{closed}}}

A tableau for a given finite set X is a finite (upside down) tree with root X in which all child nodes are obtained by applying the tableau rules to their parents. A branch in such a tableau is closed if its leaf node contains "closed". A tableau is closed if all its branches are closed. A tableau is open if at least one branch is not closed.

Below are two closed tableaux for the set

X = { r ∧ ¬ r , p ∧ ( ( ¬ p ∨ q ) ∧ ¬ q ) } {\displaystyle X=\{r\wedge \neg r,\;p\wedge ((\neg p\vee q)\wedge \neg q)\}}

Each rule application is marked at the right hand side. Both achieve the same effect, the first closes faster. The only difference is the order in which the reduction is performed.

r ∧ ¬ r , p ∧ ( ( ¬ p ∨ q ) ∧ ¬ q ) r , ¬ r , p ∧ ( ( ¬ p ∨ q ) ∧ ¬ q ) ( ∧ ) c l o s e d ( ∧ ) {\displaystyle {\dfrac {\quad {\dfrac {\quad r\wedge \neg r,\;p\wedge ((\neg p\vee q)\wedge \neg q)\quad }{r,\;\neg r,\;p\wedge ((\neg p\vee q)\wedge \neg q)}}(\wedge )}{closed}}(\wedge )}

and second, longer one, with the rules applied in a different order:

r ∧ ¬ r , p ∧ ( ( ¬ p ∨ q ) ∧ ¬ q ) r ∧ ¬ r , p , ( ( ¬ p ∨ q ) ∧ ¬ q ) ( ∧ ) r ∧ ¬ r , p , ( ¬ p ∨ q ) , ¬ q ( ∧ ) r ∧ ¬ r , p , ¬ p , ¬ q c l o s e d ( i d ) r ∧ ¬ r , p , q , ¬ q c l o s e d ( i d ) ( ∨ ) {\displaystyle {\dfrac {\quad {\dfrac {\quad {\dfrac {\quad r\wedge \neg r,\;p\wedge ((\neg p\vee q)\wedge \neg q)\quad }{r\wedge \neg r,\;p,\;((\neg p\vee q)\wedge \neg q)}}(\wedge )\quad }{r\wedge \neg r,\;p,\;(\neg p\vee q),\;\neg q}}(\wedge )}{\quad {\dfrac {\quad r\wedge \neg r,\;p,\;\neg p,\;\neg q\quad }{closed}}(id)\quad \quad {\dfrac {\quad r\wedge \neg r,\;p,\;q,\;\neg q\quad }{closed}}(id)}}(\vee )}

The first tableau closes after only one rule application while the second one misses the mark and takes a lot longer to close. Clearly, we would prefer to always find the shortest closed tableaux but it can be shown that one single algorithm that finds the shortest closed tableaux for all input sets of formulae cannot exist.[_citation needed_]

The three rules ( ∧ ) {\displaystyle (\wedge )}

Just apply all possible rules in all possible orders until we find a closed tableau for X ′ {\displaystyle X'}

or until we exhaust all possibilities and conclude that every tableau for X ′ {\displaystyle X'}

is open.

In the first case, X ′ {\displaystyle X'}

These rules suffice for all of classical logic by taking an initial set of formulae X and replacing each member C by its logically equivalent negated normal form C' giving a set of formulae X' . We know that X is satisfiable if and only if X' is satisfiable, so it suffices to search for a closed tableau for X' using the procedure outlined above.

By setting X = { ¬ A } {\displaystyle X=\{\neg A\}}

If the tableau for { ¬ A } {\displaystyle \{\neg A\}}

closes then ¬ A {\displaystyle \neg A}

is unsatisfiable and so A is a tautology since no assignment of truth values will ever make A false. Otherwise any open leaf of any open branch of any open tableau for { ¬ A } {\displaystyle \{\neg A\}}

gives an assignment that falsifies A.

Classical propositional logic usually has a connective to denote material implication. If we write this connective as ⇒, then the formula A ⇒ B stands for "if A then B". It is possible to give a tableau rule for breaking down A ⇒ B into its constituent formulae. Similarly, we can give one rule each for breaking down each of ¬(A ∧ B), ¬(A ∨ B), ¬(¬A), and ¬(A ⇒ B). Together these rules would give a terminating procedure for deciding whether a given set of formulae is simultaneously satisfiable in classical logic since each rule breaks down one formula into its constituents but no rule builds larger formulae out of smaller constituents. Thus we must eventually reach a node that contains only atoms and negations of atoms. If this last node matches (id) then we can close the branch, otherwise it remains open.

But note that the following equivalences hold in classical logic where (...) = (...) means that the left hand side formula is logically equivalent to the right hand side formula:

¬ ( A ∧ B ) = ¬ A ∨ ¬ B ¬ ( A ∨ B ) = ¬ A ∧ ¬ B ¬ ( ¬ A ) = A ¬ ( A ⇒ B ) = A ∧ ¬ B A ⇒ B = ¬ A ∨ B A ⇔ B = ( A ∧ B ) ∨ ( ¬ A ∧ ¬ B ) ¬ ( A ⇔ B ) = ( A ∧ ¬ B ) ∨ ( ¬ A ∧ B ) {\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lcl}\neg (A\land B)&=&\neg A\lor \neg B\\\neg (A\lor B)&=&\neg A\land \neg B\\\neg (\neg A)&=&A\\\neg (A\Rightarrow B)&=&A\land \neg B\\A\Rightarrow B&=&\neg A\lor B\\A\Leftrightarrow B&=&(A\land B)\lor (\neg A\land \neg B)\\\neg (A\Leftrightarrow B)&=&(A\land \neg B)\lor (\neg A\land B)\end{array}}}

If we start with an arbitrary formula C of classical logic, and apply these equivalences repeatedly to replace the left hand sides with the right hand sides in C, then we will obtain a formula C' which is logically equivalent to C but which has the property that C' contains no implications, and ¬ appears in front of atomic formulae only. Such a formula is said to be in negation normal form and it is possible to prove formally that every formula C of classical logic has a logically equivalent formula C' in negation normal form. That is, C is satisfiable if and only if C' is satisfiable.

Propositional tableau with unification

[edit]

The above rules for propositional tableau can be simplified by using uniform notation. In uniform notation, each formula is either of type α {\displaystyle \alpha }

α α 1 α 2 X ∧ Y X Y ¬ ( X ∨ Y ) ¬ X ¬ Y ¬ ( X ⟹ Y ) X ¬ Y ¬ ¬ X X X {\displaystyle {\begin{array}{c|c|c}\alpha &\alpha _{1}&\alpha _{2}\\\hline X\wedge Y&X&Y\\\neg (X\vee Y)&\neg X&\neg Y\\\neg (X\implies Y)&X&\neg Y\\\neg \neg X&X&X\\\end{array}}}

In each table, the left-most column shows all the possible structures for the formulae of type alpha or beta, and the right-most columns show their respective components. Alternatively, the rules for uniform notation can be expressed using signed formulae:

α α 1 α 2 T X ∧ Y T X T Y F X ∨ Y F X F Y F X ⟹ Y T X F Y F ¬ X T X T Y T ¬ X F X F Y β β 1 β 2 F X ∧ Y F Y F X T X ∨ Y T X T Y T X ⟹ Y F X T Y F ¬ X T X T X T ¬ X F X F Y {\displaystyle {\begin{array}{c|c|c}\alpha &\alpha _{1}&\alpha _{2}\\\hline T\,X\wedge Y&T\,\,X&T\,\,Y\\F\,\,X\vee Y&F\,\,X&F\,\,Y\\F\,\,X\implies Y&T\,\,X&F\,\,Y\\F\,\,\neg X&T\,\,X&T\,\,Y\\T\,\,\neg X&F\,\,X&F\,\,Y\end{array}}\qquad {\begin{array}{c|c|c}\beta &\beta _{1}&\beta _{2}\\\hline F\,\,X\wedge Y&F\,\,Y&F\,\,X\\T\,\,X\vee Y&T\,\,X&T\,\,Y\\T\,\,X\implies Y&F\,\,X&T\,\,Y\\F\,\,\neg X&T\,\,X&T\,\,X\\T\,\,\neg X&F\,\,X&F\,\,Y\end{array}}}

When constructing a propositional tableau using the above notation, whenever one encounters a formula of type alpha, its two components α 1 , α 2 {\displaystyle \alpha _{1},\alpha _{2}}

First-order logic tableau

[edit]

Tableaux are extended to first-order predicate logic by two rules for dealing with universal and existential quantifiers, respectively. Two different sets of rules can be used; both employ a form of Skolemization for handling existential quantifiers, but differ on the handling of universal quantifiers.

The set of formulae to check for validity is here supposed to contain no free variables; this is not a limitation as free variables are implicitly universally quantified, so universal quantifiers over these variables can be added, resulting in a formula with no free variables.

First-order tableau without unification

[edit]

A first-order formula ∀ x . γ ( x ) {\displaystyle \forall x.\gamma (x)}

( ∀ ) ∀ x . γ ( x ) γ ( t ) {\displaystyle (\forall ){\frac {\forall x.\gamma (x)}{\gamma (t)}}}

Contrarily to the rules for the propositional connectives, multiple applications of this rule to the same formula may be necessary. As an example, the set { ¬ P ( a ) ∨ ¬ P ( b ) , ∀ x . P ( x ) } {\displaystyle \{\neg P(a)\vee \neg P(b),\forall x.P(x)\}}

Existential quantifiers are dealt with by means of Skolemization. In particular, a formula with a leading existential quantifier like ∃ x . δ ( x ) {\displaystyle \exists x.\delta (x)}

( ∃ ) ∃ x . δ ( x ) δ ( c ) {\displaystyle (\exists ){\frac {\exists x.\delta (x)}{\delta (c)}}}

A tableau without unification for {∀x.P(x), ∃x.(¬P(x)⋁¬P(f(x)))}. For clarity, formulae are numbered on the left and the formula and rule used at each step is on the right

The Skolem term c {\displaystyle c}

The rule for existential quantifiers introduces new constant symbols. These symbols can be used by the rule for universal quantifiers, so that ∀ y . γ ( y ) {\displaystyle \forall y.\gamma (y)}

The above two rules for universal and existential quantifiers are correct, and so are the propositional rules: if a set of formulae generates a closed tableau, this set is unsatisfiable. Completeness can also be proved: if a set of formulae is unsatisfiable, there exists a closed tableau built from it by these rules. However, actually finding such a closed tableau requires a suitable policy of application of rules. Otherwise, an unsatisfiable set can generate an infinite-growing tableau. As an example, the set { ¬ P ( f ( c ) ) , ∀ x . P ( x ) } {\displaystyle \{\neg P(f(c)),\forall x.P(x)\}}

The rule for universal quantifiers ( ∀ ) {\displaystyle (\forall )}

First-order tableau with unification

[edit]

The main problem of tableau without unification is how to choose a ground term t {\displaystyle t}

A solution to this problem is to "delay" the choice of the term to the time when the consequent of the rule allows closing at least a branch of the tableau. This can be done by using a variable instead of a term, so that ∀ x . γ ( x ) {\displaystyle \forall x.\gamma (x)}

( ∀ ) ∀ x . γ ( x ) γ ( x ′ ) {\displaystyle (\forall ){\frac {\forall x.\gamma (x)}{\gamma (x')}}}

While the initial set of formulae is supposed not to contain free variables, a formula of the tableau may contain the free variables generated by this rule. These free variables are implicitly considered universally quantified.

This rule employs a variable instead of a ground term. What is gained by this change is that these variables can be then given a value when a branch of the tableau can be closed, solving the problem of generating terms that might be useless.

As an example, { ¬ P ( a ) , ∀ x . P ( x ) } {\displaystyle \{\neg P(a),\forall x.P(x)\}}

This rule closes at least a branch of the tableau—the one containing the considered pair of literals. However, the substitution has to be applied to the whole tableau, not only on these two literals. This is expressed by saying that the free variables of the tableau are rigid: if an occurrence of a variable is replaced by something else, all other occurrences of the same variable must be replaced in the same way. Formally, the free variables are (implicitly) universally quantified and all formulae of the tableau are within the scope of these quantifiers.

Existential quantifiers are dealt with by Skolemization. Contrary to the tableau without unification, Skolem terms may not be simple constants. Indeed, formulae in a tableau with unification may contain free variables, which are implicitly considered universally quantified. As a result, a formula like ∃ x . δ ( x ) {\displaystyle \exists x.\delta (x)}

( ∃ ) ∃ x . δ ( x ) δ ( f ( x 1 , … , x n ) ) {\displaystyle (\exists ){\frac {\exists x.\delta (x)}{\delta (f(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{n}))}}}

A first-order tableau with unification for {∀x.P(x), ∃x.(¬P(x)⋁¬P(f(x)))}. For clarity, formulae are numbered on the left and the formula and rule used at each step is on the right

This rule incorporates a simplification over a rule where x 1 , … , x n {\displaystyle x_{1},\ldots ,x_{n}}

The formula represented by a tableau is obtained in a way that is similar to the propositional case, with the additional assumption that free variables are considered universally quantified. As for the propositional case, formulae in each branch are conjoined and the resulting formulae are disjoined. In addition, all free variables of the resulting formula are universally quantified. All these quantifiers have the whole formula in their scope. In other words, if F {\displaystyle F}

- The assumption that free variables are universally quantified is what makes the application of a most general unifier a sound rule: since γ ( x ′ ) {\displaystyle \gamma (x')}

means that γ {\displaystyle \gamma }

is true for every possible value of x ′ {\displaystyle x'}

, then γ ( t ) {\displaystyle \gamma (t)}

is true for the term t {\displaystyle t}

that the most general unifier replaces x {\displaystyle x}

with.

- Free variables in a tableau are rigid: all occurrences of the same variable have to be replaced all with the same term. Every variable can be considered a symbol representing a term that is yet to be decided. This is a consequence of free variables being assumed universally quantified over the whole formula represented by the tableau: if the same variable occurs free in two different nodes, both occurrences are in the scope of the same quantifier. As an example, if the formulae in two nodes are A ( x ) {\displaystyle A(x)}

and B ( x ) {\displaystyle B(x)}

, where x {\displaystyle x}

is free in both, the formula represented by the tableau is something in the form ∀ x . ( . . . A ( x ) . . . B ( x ) . . . ) {\displaystyle \forall x.(...A(x)...B(x)...)}

. This formula implies that ( . . . A ( x ) . . . B ( x ) . . . ) {\displaystyle (...A(x)...B(x)...)}

is true for any value of x {\displaystyle x}

, but does not in general imply ( . . . A ( t ) . . . A ( t ′ ) . . . ) {\displaystyle (...A(t)...A(t')...)}

for two different terms t {\displaystyle t}

and t ′ {\displaystyle t'}

, as these two terms may in general take different values. This means that x {\displaystyle x}

cannot be replaced by two different terms in A ( x ) {\displaystyle A(x)}

and B ( x ) {\displaystyle B(x)}

.

- Free variables in a formula to check for validity are also considered universally quantified. However, these variables cannot be left free when building a tableau, because tableau rules works on the converse of the formula but still treats free variables as universally quantified. For example, P ( x ) → P ( c ) {\displaystyle P(x)\rightarrow P(c)}

is not valid (it is not true in the model where D = { 1 , 2 } , P ( 1 ) = ⊥ , P ( 2 ) = ⊤ , c = 1 {\displaystyle D=\{1,2\},P(1)=\bot ,P(2)=\top ,c=1}

, and the interpretation where x = 2 {\displaystyle x=2}

). Consequently, { P ( x ) , ¬ P ( c ) } {\displaystyle \{P(x),\neg P(c)\}}

is satisfiable (it is satisfied by the same model and interpretation). However, a closed tableau could be generated with P ( x ) {\displaystyle P(x)}

and ¬ P ( c ) {\displaystyle \neg P(c)}

, and substituting x {\displaystyle x}

with c {\displaystyle c}

would generate a closure. A correct procedure is to first make universal quantifiers explicit, thus generating ∀ x . ( P ( x ) → P ( c ) ) {\displaystyle \forall x.(P(x)\rightarrow P(c))}

.

The following two variants are also correct.

- Applying to the whole tableau a substitution to the free variables of the tableau is a correct rule, provided that this substitution is free for the formula representing the tableau. In other worlds, applying such a substitution leads to a tableau whose formula is still a consequence of the input set. Using most general unifiers automatically ensures that the condition of freeness for the tableau is met.

- While in general every variable has to be replaced with the same term in the whole tableau, there are some special cases in which this is not necessary.

Tableaux with unification can be proved complete: if a set of formulae is unsatisfiable, it has a tableau-with-unification proof. However, actually finding such a proof may be a difficult problem. Contrarily to the case without unification, applying a substitution can modify the existing part of a tableau; while applying a substitution closes at least a branch, it may make other branches impossible to close (even if the set is unsatisfiable).

A solution to this problem is delayed instantiation: no substitution is applied until one that closes all branches at the same time is found. With this variant, a proof for an unsatisfiable set can always be found by a suitable policy of application of the other rules. This method however requires the whole tableau to be kept in memory: the general method closes branches, which can be then discarded, while this variant does not close any branch until the end.

The problem that some tableaux that can be generated are impossible to close even if the set is unsatisfiable is common to other sets of tableau expansion rules: even if some specific sequences of application of these rules allow constructing a closed tableau (if the set is unsatisfiable), some other sequences lead to tableaux that cannot be closed. General solutions for these cases are outlined in the "Searching for a tableau" section.

Tableau calculi and their properties

[edit]

A tableau calculus is a set of rules that allows building and modification of a tableau. Propositional tableau rules, tableau rules without unification, and tableau rules with unification, are all tableau calculi. Some important properties a tableau calculus may or may not possess are completeness, destructiveness, and proof confluence.

A tableau calculus is called complete if it allows building a tableau proof for every given unsatisfiable set of formulae. The tableau calculi mentioned above can be proved complete.

A remarkable difference between tableau with unification and the other two calculi is that the latter two calculi only modify a tableau by adding new nodes to it, while the former one allows substitutions to modify the existing part of the tableau. More generally, tableau calculi are classed as destructive or non-destructive depending on whether they only add new nodes to tableau or not. Tableau with unification is therefore destructive, while propositional tableau and tableau without unification are non-destructive.

Proof confluence is the property of a tableau calculus being able to obtain a proof for an arbitrary unsatisfiable set from an arbitrary tableau, assuming that this tableau has itself been obtained by applying the rules of the calculus. In other words, in a proof confluent tableau calculus, from an unsatisfiable set one can apply whatever set of rules and still obtain a tableau from which a closed one can be obtained by applying some other rules.

A tableau calculus is simply a set of rules that prescribes how a tableau can be modified. A proof procedure is a method for actually finding a proof (if one exists). In other words, a tableau calculus is a set of rules, while a proof procedure is a policy of application of these rules. Even if a calculus is complete, not every possible choice of application of rules leads to a proof of an unsatisfiable set. For example, { P ( f ( c ) ) , R ( c ) , ¬ P ( f ( c ) ) ∨ ¬ R ( c ) , ∀ x . Q ( x ) } {\displaystyle \{P(f(c)),R(c),\neg P(f(c))\vee \neg R(c),\forall x.Q(x)\}}

For proof procedures, a definition of completeness has been given: a proof procedure is strongly complete if it allows finding a closed tableau for any given unsatisfiable set of formulae. Proof confluence of the underlying calculus is relevant to completeness: proof confluence is the guarantee that a closed tableau can be always generated from an arbitrary partially constructed tableau (if the set is unsatisfiable). Without proof confluence, the application of a 'wrong' rule may result in the impossibility of making the tableau complete by applying other rules.

Propositional tableaux and tableaux without unification have strongly complete proof procedures. In particular, a complete proof procedure is that of applying the rules in a fair way. This is because the only way such calculi cannot generate a closed tableau from an unsatisfiable set is by not applying some applicable rules.

For propositional tableaux, fairness amounts to expanding every formula in every branch. More precisely, for every formula and every branch the formula is in, the rule having the formula as a precondition has been used to expand the branch. A fair proof procedure for propositional tableaux is strongly complete.

For first-order tableaux without unification, the condition of fairness is similar, with the exception that the rule for universal quantifiers might require more than one application. Fairness amounts to expanding every universal quantifier infinitely often. In other words, a fair policy of application of rules cannot keep applying other rules without expanding every universal quantifier in every branch that is still open once in a while.

Searching for a closed tableau

[edit]

If a tableau calculus is complete, every unsatisfiable set of formulae has an associated closed tableau. While this tableau can always be obtained by applying some of the rules of the calculus, the problem of which rules to apply for a given formula still remains. As a result, completeness does not automatically imply the existence of a feasible policy of application of rules that always leads to a closed tableau for every given unsatisfiable set of formulae. While a fair proof procedure is complete for ground tableau and tableau without unification, this is not the case for tableau with unification.

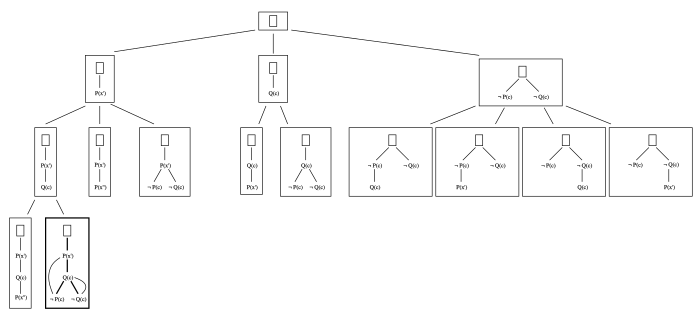

A search tree in the space of tableaux for {∀x.P(x), ¬P(c)⋁¬Q(c), ∃y.Q(c)}. For simplicity, the formulae of the set have been omitted from all tableau in the figure and a rectangle used in their place. A closed tableau is in the bold box; the other branches could be still expanded.

A general solution for this problem is that of searching the space of tableaux until a closed one is found (if any exists, that is, the set is unsatisfiable). In this approach, one starts with an empty tableau and then recursively applies every possible applicable rule. This procedure visits a (implicit) tree whose nodes are labeled with tableaux, and such that the tableau in a node is obtained from the tableau in its parent by applying one of the valid rules.

Since each branch can be infinite, this tree has to be visited breadth-first rather than depth-first. This requires a large amount of space, as the breadth of the tree can grow exponentially. A method that may visit some nodes more than once but works in polynomial space is to visit in a depth-first manner with iterative deepening: one first visits the tree depth first up to a certain depth, then increases the depth and perform the visit again. This particular procedure uses the depth (which is also the number of tableau rules that have been applied) for deciding when to stop at each step. Various other parameters (such as the size of the tableau labeling a node) have been used instead.

The size of the search tree depends on the number of (children) tableaux that can be generated from a given (parent) one. Reducing the number of such tableaux therefore reduces the required search.

A way for reducing this number is to disallow the generation of some tableaux based on their internal structure. An example is the condition of regularity: if a branch contains a literal, using an expansion rule that generates the same literal is useless because the branch containing two copies of the literals would have the same set of formulae of the original one. This expansion can be disallowed because if a closed tableau exists, it can be found without it. This restriction is structural because it can be checked by looking at the structure of the tableau to expand only.

Different methods for reducing search disallow the generation of some tableaux on the ground that a closed tableau can still be found by expanding the other ones. These restrictions are called global. As an example of a global restriction, one may employ a rule that specifies which of the open branches is to be expanded. As a result, if a tableau has for example two non-closed branches, the rule specifies which one is to be expanded, disallowing the expansion of the second one. This restriction reduces the search space because one possible choice is now forbidden; completeness is however not harmed, as the second branch will still be expanded if the first one is eventually closed. As an example, a tableau with root ¬ a ∧ ¬ b {\displaystyle \neg a\wedge \neg b}

When applied to sets of clauses (rather than of arbitrary formulae), tableaux methods allow for a number of efficiency improvements. A first-order clause is a formula ∀ x 1 , … , x n L 1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ L m {\displaystyle \forall x_{1},\ldots ,x_{n}L_{1}\vee \cdots \vee L_{m}}

The only expansion rules that are applicable to a clause are ( ∀ ) {\displaystyle (\forall )}

( C ) L 1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ L n L 1 ′ | ⋯ | L n ′ {\displaystyle (C){\frac {L_{1}\vee \cdots \vee L_{n}}{L_{1}'|\cdots |L_{n}'}}}

When the set to be checked for satisfiability is only composed of clauses, this and the unification rules are sufficient to prove unsatisfiability. In other worlds, the tableau calculi composed of ( C ) {\displaystyle (C)}

Since the clause expansion rule only generates literals and never new clauses, the clauses to which it can be applied are only clauses of the input set. As a result, the clause expansion rule can be further restricted to the case where the clause is in the input set.

( C ) L 1 ∨ ⋯ ∨ L n L 1 ′ | ⋯ | L n ′ {\displaystyle (C){\frac {L_{1}\vee \cdots \vee L_{n}}{L_{1}'|\cdots |L_{n}'}}}

Since this rule directly exploits the clauses in the input set there is no need to initialize the tableau to the chain of the input clauses. The initial tableau can therefore be initialize with the single node labeled t r u e {\displaystyle true}

A number of optimizations can be used for clause tableau. These optimization are aimed at reducing the number of possible tableaux to be explored when searching for a closed tableau as described in the "Searching for a closed tableau" section above.

Connection is a condition over tableau that forbids expanding a branch using clauses that are unrelated to the literals that are already in the branch. Connection can be defined in two ways:

strong connectedness

when expanding a branch, use an input clause only if it contains a literal that can be unified with the negation of the literal in the current leaf

weak connectedness

allow the use of clauses that contain a literal that unifies with the negation of a literal on the branch

Both conditions apply only to branches consisting not only of the root. The second definition allows for the use of a clause containing a literal that unifies with the negation of a literal in the branch, while the first only further constraint that literal to be in leaf of the current branch.

If clause expansion is restricted by connectedness (either strong or weak), its application produces a tableau in which substitution can applied to one of the new leaves, closing its branch. In particular, this is the leaf containing the literal of the clause that unifies with the negation of a literal in the branch (or the negation of the literal in the parent, in case of strong connection).

Both conditions of connectedness lead to a complete first-order calculus: if a set of clauses is unsatisfiable, it has a closed connected (strongly or weakly) tableau. Such a closed tableau can be found by searching in the space of tableaux as explained in the "Searching for a closed tableau" section. During this search, connectedness eliminates some possible choices of expansion, thus reducing search. In other worlds, while the tableau in a node of the tree can be in general expanded in several different ways, connection may allow only few of them, thus reducing the number of resulting tableaux that need to be further expanded.

This can be seen on the following (propositional) example. The tableau made of a chain t r u e − a {\displaystyle true-a}

The connectedness conditions, when applied to the propositional (clausal) case, make the resulting calculus non-confluent. As an example, { a , b , ¬ b } {\displaystyle \{a,b,\neg b\}}

A tableau is regular if no literal occurs twice in the same branch. Enforcing this condition allows for a reduction of the possible choices of tableau expansion, as the clauses that would generate a non-regular tableau cannot be expanded.

These disallowed expansion steps are however useless. If B {\displaystyle B}

Tableaux for modal logics

[edit]

In a modal logic, a model comprises a set of possible worlds, each one associated to a truth evaluation; an accessibility relation specifies when a world is accessible from another one. A modal formula may specify not only conditions over a possible world, but also on the ones that are accessible from it. As an example, ◻ A {\displaystyle \Box A}

As for propositional logic, tableaux for modal logics are based on recursively breaking formulae into its basic components. Expanding a modal formula may however require stating conditions over different worlds. As an example, if ¬ ◻ A {\displaystyle \neg \Box A}

¬ ◻ A ¬ A {\displaystyle {\frac {\neg \Box A}{\neg A}}}

In propositional tableaux all formulae refer to the same truth evaluation, but the precondition of the rule above holds in one world while the consequence holds in another. Not taking this into account would generate incorrect results. For example, formula a ∧ ¬ ◻ a {\displaystyle a\wedge \neg \Box a}

Technically, tableaux for modal logics check the satisfiability of a set of formulae: they check whether there exists a model M {\displaystyle M}

This fact has an important consequence: formulae that hold in a world may imply conditions over different successors of that world. Unsatisfiability may then be proved from the subset of formulae referring to a single successor. This holds if a world may have more than one successor, which is true for most modal logics. If this is the case, a formula like ¬ ◻ A ∧ ¬ ◻ B {\displaystyle \neg \Box A\wedge \neg \Box B}

Depending on whether the precondition and consequence of a tableau expansion rule refer to the same world or not, the rule is called static or transactional. While rules for propositional connectives are all static, not all rules for modal connectives are transactional: for example, in every modal logic including axiom T, it holds that ◻ A {\displaystyle \Box A}

Formula-deleting tableau

[edit]

A method for avoiding formulae referring to different worlds interacting in the wrong way is to make sure that all formulae of a branch refer to the same world. This condition is initially true as all formulae in the set to be checked for consistency are assumed referring to the same world. When expanding a branch, two situations are possible: either the new formulae refer to the same world as the other one in the branch or not. In the first case, the rule is applied normally. In the second case, all formulae of the branch that do not also hold in the new world are deleted from the branch, and possibly added to all other branches that are still relative to the old world.

As an example, in S5 every formula ◻ A {\displaystyle \Box A}

World-labeled tableau

[edit]

A different mechanism for ensuring the correct interaction between formulae referring to different worlds is to switch from formulae to labeled formulae: instead of writing A {\displaystyle A}

All propositional expansion rules are adapted to this variant by stating that they all refer to formulae with the same world label. For example, w : A ∧ B {\displaystyle w:A\wedge B}

A modal expansion rule may have a consequence that refers to different worlds. For example, the rule for ¬ ◻ A {\displaystyle \neg \Box A}

w : ¬ ◻ A w ′ : ¬ A {\displaystyle {\frac {w:\neg \Box A}{w':\neg A}}}

The precondition and consequent of this rule refer to worlds w {\displaystyle w}

Set-labeling tableaux

[edit]

The problem of interaction between formulae holding in different worlds can be overcome by using set-labeling tableaux. These are trees whose nodes are labeled with sets of formulae; the expansion rules explain how to attach new nodes to a leaf, based only on the label of the leaf (and not on the label of other nodes in the branch).

Tableaux for modal logics are used to verify the satisfiability of a set of modal formulae in a given modal logic. Given a set of formulae S {\displaystyle S}

The expansion rules depend on the particular modal logic used. A tableau system for the basic modal logic K can be obtained by adding to the propositional tableau rules the following one:

( K ) ◻ A 1 ; … ; ◻ A n ; ¬ ◻ B A 1 ; … ; A n ; ¬ B {\displaystyle (K){\frac {\Box A_{1};\ldots ;\Box A_{n};\neg \Box B}{A_{1};\ldots ;A_{n};\neg B}}}

Intuitively, the precondition of this rule expresses the truth of all formulae A 1 , … , A n {\displaystyle A_{1},\ldots ,A_{n}}

More technically, modal tableaux methods check the existence of a model M {\displaystyle M}

While the preconditions ◻ A 1 ; … ; ◻ A n ; ¬ ◻ B {\displaystyle \Box A_{1};\ldots ;\Box A_{n};\neg \Box B}

As a result of the possibly different worlds where formulae are assumed true, a formula in a node is not automatically valid in all its descendants, as every application of the modal rule corresponds to a move from a world to another one. This condition is automatically captured by set-labeling tableaux, as expansion rules are based only on the leaf where they are applied and not on its ancestors.

Notably, ( K ) {\displaystyle (K)}

Differently from the propositional rules, ( K ) {\displaystyle (K)}

( θ ) A 1 ; … ; A n ; B 1 ; … ; B m A 1 ; … ; A n {\displaystyle (\theta ){\frac {A_{1};\ldots ;A_{n};B_{1};\ldots ;B_{m}}{A_{1};\ldots ;A_{n}}}}

The addition of this rule (thinning rule) makes the resulting calculus non-confluent: a tableau for an inconsistent set may be impossible to close, even if a closed tableau for the same set exists.

Rule ( θ ) {\displaystyle (\theta )}

This non-determinism can be avoided by restricting the usage of ( θ ) {\displaystyle (\theta )}

Axiom T expresses reflexivity of the accessibility relation: every world is accessible from itself. The corresponding tableau expansion rule is:

( T ) A 1 ; … ; A n ; ◻ B A 1 ; … ; A n ; ◻ B ; B {\displaystyle (T){\frac {A_{1};\ldots ;A_{n};\Box B}{A_{1};\ldots ;A_{n};\Box B;B}}}

This rule relates conditions over the same world: if ◻ B {\displaystyle \Box B}

This rule copies ◻ B {\displaystyle \Box B}

A different method for dealing with formulae holding in alternate worlds is to start a different tableau for each new world that is introduced in the tableau. For example, ¬ ◻ A {\displaystyle \neg \Box A}

The above modal tableaux establish the consistency of a set of formulae, and can be used for solving the local logical consequence problem. This is the problem of telling whether, for each model M {\displaystyle M}

A related problem is the global consequence problem, where the assumption is that a formula (or set of formulae) G {\displaystyle G}

Local and global assumption differ on models where the assumed formula is true in some worlds but not in others. As an example, { P , ¬ ◻ ( P ∧ Q ) } {\displaystyle \{P,\neg \Box (P\wedge Q)\}}

These two problems can be combined, so that one can check whether B {\displaystyle B}

The following conventions are sometimes used.

When writing tableaux expansion rules, formulae are often denoted using a convention, so that for example α {\displaystyle \alpha }

| Notation | Formulae | ||

|---|---|---|---|

α {\displaystyle \alpha }  |

α 1 ∧ α 2 {\displaystyle \alpha _{1}\wedge \alpha _{2}}  |

¬ ( α 1 ¯ ∨ α 2 ¯ ) {\displaystyle \neg ({\overline {\alpha _{1}}}\vee {\overline {\alpha _{2}}})}  |

¬ ( α 1 → α 2 ¯ ) {\displaystyle \neg (\alpha _{1}\rightarrow {\overline {\alpha _{2}}})}  |

β {\displaystyle \beta }  |

β 1 ∨ β 2 {\displaystyle \beta _{1}\vee \beta _{2}}  |

β 1 ¯ → β 2 {\displaystyle {\overline {\beta _{1}}}\rightarrow \beta _{2}}  |

¬ ( β 1 ¯ ∧ β 2 ¯ ) {\displaystyle \neg ({\overline {\beta _{1}}}\wedge {\overline {\beta _{2}}})}  |

γ {\displaystyle \gamma }  |

∀ x γ 1 ( x ) {\displaystyle \forall x\gamma _{1}(x)}  |

¬ ∃ x γ 1 ( x ) ¯ {\displaystyle \neg \exists x{\overline {\gamma _{1}(x)}}}  |

|

δ {\displaystyle \delta }  |

∃ x δ 1 ( x ) {\displaystyle \exists x\delta _{1}(x)}  |

¬ ∀ x δ 1 ( x ) ¯ {\displaystyle \neg \forall x{\overline {\delta _{1}(x)}}}  |

|

π {\displaystyle \pi }  |

◊ π 1 {\displaystyle \Diamond \pi _{1}}  |

¬ ◻ π 1 ¯ {\displaystyle \neg \Box {\overline {\pi _{1}}}}  |

|

ν {\displaystyle \nu }  |

◻ ν 1 {\displaystyle \Box \nu _{1}}  |

¬ ◊ ν 1 ¯ {\displaystyle \neg \Diamond {\overline {\nu _{1}}}}  |

Each label in the first column is taken to be either formula in the other columns. An overlined formula such as α 1 ¯ {\displaystyle {\overline {\alpha _{1}}}}

Since every label indicates many equivalent formulae, this notation allows writing a single rule for all these equivalent formulae. For example, the conjunction expansion rule is formulated as:

( α ) α α 1 α 2 {\displaystyle (\alpha ){\frac {\alpha }{\begin{array}{c}\alpha _{1}\\\alpha _{2}\end{array}}}}

A formula in a tableau is assumed true. Signed tableaux allows stating that a formula is false. This is generally achieved by adding a label to each formula, where the label T indicates formulae assumed true and F those assumed false. A different but equivalent notation is that to write formulae that are assumed true at the left of the node and formulae assumed false at its right.

- ^ a b c d e f g Howson, Colin (1997). Logic with trees: an introduction to symbolic logic. London; New York: Routledge. pp. ix, x, 24–29, 47. ISBN 978-0-415-13342-5.

- ^ a b c Restall, Greg (2006). Logic: an introduction. Fundamentals of philosophy. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 5, 42, 55. ISBN 978-0-415-40067-1. OCLC 63115330.

- ^ Howson 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Girle 2014.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Philosophy 2023.

- ^ Beth 1955.

- ^ Smullyan 1995.

- ^ Carnielli 1987.

- ^ Carnielli 1991.

- ^ Plato, Jan von (2013). Elements of logical reasoning (1. publ ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-107-03659-8.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Connective". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ A variant to this starting step is to begin with a single-node tree whose root is labeled by ⊤ {\displaystyle \top }

. In this second case, the procedure can always copy a formula in the set below a leaf. As a running example, the tableau for the set { ( a ∨ ¬ b ) ∧ b , ¬ a } {\displaystyle \{(a\vee \neg b)\wedge b,\neg a\}}

is shown.

- ^ An applicable node is a node whose outermost connective corresponds to an expansion rule, and which has not already been applied at any prior node on the selected leaf node's branch.

- ^ Smullyan 2014, pp. 88–89.

- Beth, Evert W. (1955). "Semantic entailment and formal derivability". Mededelingen van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Afdeling Letterkunde. 18 (13): 309–42. Reprinted in Intikka, Jaakko, ed. (1969). The Philosophy of Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-875011-6.

- Bostock, David (1997). Intermediate Logic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-156707-0.

- Carnielli, Walter A. (1987). "Systematization of Finite Many-Valued Logics Through the Method of Tableaux". The Journal of Symbolic Logic. 52 (2): 473–493. doi:10.2307/2274395. JSTOR 2274395. S2CID 42822367.

- Carnielli, Walter A. (1991). "On sequents and tableaux for many-valued logics" (PDF). The Journal of Non-Classical Logics. 8 (1): 59–76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- D'Agostino, M.; Gabbay, D.; Haehnle, R.; Posegga, J., eds. (1999). Handbook of Tableau Methods. Kluwer. ISBN 978-94-017-1754-0.

- Fitting, Melvin (1996) [1990]. First-order logic and automated theorem proving (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2360-3. ISBN 978-1-4612-7515-2. S2CID 10411039.

- Girle, Rod (2014). Modal Logics and Philosophy (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-49217-7.

- Goré, Rajeev. "Tableau Methods for Modal and Temporal Logics". Handbook of Tableau Methods. pp. 297–396.

- Hähnle, Reiner (2001). "3. Tableaux and Related Methods". In Robinson, Alan J.A.; Voronkov, Andrei (eds.). Handbook of Automated Reasoning. Elsevier. pp. 101–179. ISBN 978-0-08-053279-0.

- Howson, Colin (11 October 2005) [1997]. Logic with trees: an introduction to symbolic logic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-78550-6.

- Jeffrey, Richard (2006) [1967]. Formal Logic: Its Scope and Limits (4th ed.). Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-813-1.

- Letz, Reinhold; Stenz, Gernot. "28. Model Elimination and Connection Tableau Procedures". Handbook of Automated Reasoning. pp. 2015–2114.

- Smullyan, Raymond (1995) [1968]. First Order-Logic. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-68370-6.

- Smullyan, Raymond (2014). A Beginner's Guide to Mathematical Logic. Dover. ISBN 978-0486492377.

- The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. (11 December 2023). "Modern Logic: The Boolean Period: Carroll". The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- Zeman, Joseph Jay (1973). Modal Logic: The Lewis-modal Systems. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-824374-8. OCLC 641504.

- TABLEAUX: an annual international conference on automated reasoning with analytic tableaux and related methods

- JAR: Journal of Automated Reasoning

- The tableaux package: an interactive prover for propositional and first-order logic using tableaux

- Tree proof generator: another interactive prover for propositional and first-order logic using tableaux

- LoTREC: a generic tableaux-based prover for modal logics from IRIT/Toulouse University

- Intro to Truth Trees on YouTube