Myles Coverdale (original) (raw)

English preacher and theologian (1488–1569)

| The Right ReverendMyles Coverdale | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Exeter | |

|

|

| Church | Church of England |

| See | Exeter |

| Installed | 1551 |

| Term ended | 1553 |

| Predecessor | John Vesey |

| Successor | John Vesey |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 30 August 1551by Thomas Cranmer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1488Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 20 January 1569 (aged 80-81)London, England |

| Buried | Church of St Bartholomew-by-the-Exchange, then St Magnus-the-Martyr, both in the City of London |

| Denomination | Catholicism; later an early Anglican reformer and regarded as "proto-Puritan" in his later life. |

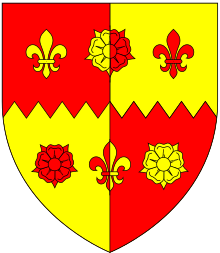

Arms of Myles Coverdale: Quarterly per fess indented gules and or, in chief a rose between two fleurs-de-lys in base a fleur-de-lys between two roses all counter-changed[1]

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles (c. 1488 – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher, hymnist and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553).[2] In 1535, Coverdale produced the first printed translation of the full Bible into Early Modern English, completing the translations of William Tyndale.[3]

His theological development is a paradigm of the progress of the English Reformation from 1530 to 1552. By the time of his death, he had transitioned into an early Puritan, affiliated to Calvin, and a friend of John Knox.

Life to end of 1528

[edit]

Regarding his probable birth county, Daniell cites John Bale, author of a sixteenth-century scriptorium, giving it as Yorkshire.[2][note 1] His birth date is generally regarded as 1488.

Coverdale studied philosophy and theology at Cambridge, becoming bachelor of canon law in 1513.[2][note 2] In 1514 John Underwood, a suffragan bishop and archdeacon of Norfolk, ordained him priest in Norwich. He entered the house of the Augustinian friars in Cambridge, where Robert Barnes had returned from Louvain to become its prior. This is thought to have been about 1520–1525.[2]According to Trueman,[4] Barnes returned to Cambridge in the early to mid-1520s.[note 3] At Louvain Barnes had studied under Erasmus and had developed humanist sympathies. In Cambridge, he read aloud to his students from St. Paul's epistles in translation and taught from classical authors.[2] This undoubtedly influenced them towards Reform. In February 1526, Coverdale was part of a group of friars that travelled from Cambridge to London to present the defence of their superior, after Barnes was summoned before Cardinal Wolsey.[2][4] Barnes had been arrested as a heretic after being accused of preaching Lutheran views in the church of St Edward King and Martyr, Cambridge on Christmas Eve. Coverdale is said to have acted as Barnes' secretary during the trial.[5] By the standards of the time, Barnes received relatively lenient treatment, being made to do public penance by carrying a faggot to St Paul's Cross.[4] However on 10 June 1539, Parliament passed the Act of Six Articles, marking a turning point in the progress of radical protestantism.[6]: 423–424 Barnes was burned at the stake on 30 July 1540, at Smithfield, along with two other reformers. Also executed that day were three Roman Catholics, who were hanged, drawn and quartered.[4]

Coverdale probably met Thomas Cromwell some time before 1527. A letter survives showing that later, in 1531, he wrote to Cromwell, requesting his guidance on his behaviour and preaching; also stating his need for books.[2] By Lent 1528, he had left the Augustinians and, wearing simple garments, was preaching in Essex against transubstantiation, the veneration of sacred images, and Confession to a Priest. At that date, such views were very dangerous, for the future course of the religious revolution that began during the reign of Henry VIII was as yet very uncertain. Reforms, both of the forms proposed by Lollardy, and those preached by Luther, were being pursued by a vigorous campaign against heresy.[6]: 379–380 Consequently, towards the end of 1528, Coverdale fled from England to the Continent.[2]

From 1528 to 1535 Coverdale spent most of his time in continental Europe, mainly in Antwerp. Celia Hughes believes that upon arriving there, he rendered considerable assistance to William Tyndale in his revisions and partial completion of his English versions of the Bible.[7]: 100 [note 4]

In 1531, Tyndale spoke to Stephen Vaughan of his poverty and the hardships of exile, although he was relatively safe in the English House in Antwerp, where the inhabitants supposedly enjoyed diplomatic immunity.[8] However, in the spring of 1535 a "debauched and villainous young Englishman wanting money" named Henry Phillips insinuated himself into Tyndale's trust. Phillips had gambled away money from his father and had fled abroad. He promised the authorities of the Holy Roman Emperor that he would betray Tyndale for cash. On the morning of 21 May 1535, having arranged for the imperial officers to be ready, Phillips tricked Tyndale into leaving the English House, whereupon he was immediately seized. Tyndale languished in prison throughout the remainder of 1535 and despite attempts to have him released, organised by Cromwell through Thomas Poyntz at the English House, Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake in October 1536.

Meanwhile Coverdale continued his work alone to produce what became the first complete English Bible in print, namely the Coverdale Bible. Not proficient in Hebrew or Greek, he used Latin, English and German sources plus the translations of Tyndale himself.

Coverdale's translation of the Bible, 1535

[edit]

In 1534 Canterbury Convocation petitioned Henry VIII that the whole Bible might be translated into English. Consequently, in 1535, Coverdale dedicated this complete Bible to the King.[9]: 201 After much scholarly debate, it is now considered very probable that the place of printing of the Coverdale Bible was Antwerp.[2][10] The printing was financed by Jacobus van Meteren. The printing of the first edition was finished on 4 October 1535.[note 5]

Coverdale based the text in part on Tyndale's translation of the New Testament (following Tyndale's November 1534 Antwerp edition) and of those books which were translated by Tyndale: the Pentateuch, and the Book of Jonah. Other Old Testament books he translated from the German of Luther and others.[note 6] [note 7]

Based on Coverdale's translation of the Book of Psalms in his 1535 Bible, his later Psalter has remained in use in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer to the present day, and is retained with various minor corrections in the 1926 Irish Book of Common Prayer, the 1928 US Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, and the 1962 Canadian Book of Common Prayer, etc.[note 8]

Further translations, 1537–1539

[edit]

In 1537 the Matthew Bible was printed, also in Antwerp, at the expense of Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch who issued it in London.[9]: 1058 It comprised Tyndale's Pentateuch; a version of Joshua 2 and Chronicles translated from the Hebrew, probably by Tyndale and not previously published; the remainder of the Old Testament from Coverdale; Tyndale's New Testament from 1535. It was dedicated to Henry VIII who licensed it for general reading. "Thomas Matthew", the supposed editor, was an alias for John Rogers.

The Matthew Bible was theologically controversial.[12] Furthermore it bore evidence of its origin from Tyndale. If Henry VIII had become aware of this, the position of Cromwell and Cranmer would have been precarious. Consequently in 1538 Coverdale was sent to Paris by Cromwell to superintend the printing of the planned "Great Bible".[note 9] François Regnault, who had supplied all English service books from 1519 to 1534, was selected as the printer because his typography was more sumptuous than that available in England.[2] According to Kenyon, the assent of the French king was obtained.[12] In May 1538 printing began. Nevertheless, a coalition of English bishops together with French theologians at the Sorbonne interfered with the operations and the Pope issued an edict that the English Bibles should be burned and the presses stopped. Some completed sheets were seized, but Coverdale rescued others, together with the type, transferring them to London.[note 10] Ultimately, the work was completed in London by Grafton and Whitchurch.[note 11]

Also in 1538, editions were published, both in Paris and in London, of a diglot (dual-language) New Testament. In this, Coverdale compared the Latin Vulgate text with his own English translation, in parallel columns on each page.[13][14][note 12]

An injunction was issued by Cromwell in September 1538, strengthening an earlier one that had been issued but widely ignored in 1536. This second injunction firmly declared opposition to "pilgrimages, feigned relics, or images, or any such superstitions" whilst correspondingly placing heavy emphasis on scripture as "the very lively word of God". Coverdale’s Great Bible was now almost ready for circulation and the injunction called for the use of "one book of the whole Bible of the largest volume" in every English church.[15][16] However at the time insufficient Great Bibles were actually printed in London so an edition of the Matthew Bible that had been re-edited by Coverdale started to be used.[note 13] The laity were also intended to learn other core items of worship in English, including the Creed, the Lord's Prayer and the Ten Commandments.[6]: 406

In February 1539, Coverdale was in Newbury communicating with Thomas Cromwell.[17] The printing of the London edition of the Great Bible was in progress.[2] It was finally published in April of the same year.[18] John Winchcombe, son of "Jack O'Newbury", a famous clothier, served as a confidential messenger to Coverdale who was performing an ecclesiastical visitation. Coverdale commended Winchcombe for his true heart towards the King's Highness and in 1540, Henry VIII granted to Winchcombe the manor of Bucklebury, a former demesne of Reading Abbey.[19]Also from Newbury, Coverdale reported to Cromwell via Winchcombe about breaches in the king's laws against papism, sought out churches in the district where the sanctity of Becket was still maintained, and arranged to burn primers and other church books which had not been altered to match the king's proceedings.

Sometime between 1535 and 1540 (the exact dates being uncertain), separate printings were made of Coverdale's translations into English of the psalms. These first versions of his psalm renditions were based mainly or completely upon his translation of the Book of Psalms in the 1535 Coverdale Bible.

In the final years of the decade, the conservative clerics, led by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, were rapidly recovering their power and influence, opposing Cromwell's policies.[2] On 28 June 1539 the Act of Six Articles became law, ending official tolerance of religious reform. Cromwell was executed on 28 July 1540.[15] This was close to the date of the burning of Coverdale's Augustinian mentor Robert Barnes. Cromwell had protected Coverdale since at least 1527 and the latter was obliged to seek refuge again.

Second exile, 1540–1547

[edit]

In April 1540 there was a second edition of the Great Bible, this time with a prologue by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. For this reason, the Great Bible is sometimes known as Cranmer’s Bible although he had no part in its translation. According to Kenyon,[12] there were seven editions in total, up until the end of 1541, with the later versions including some revisions.

Before leaving England, Coverdale married Elizabeth Macheson (d. 1565), a Scotswoman of noble family who had come to England with her sister and brother-in-law as religious exiles from Scotland.[2] They went first to Strasbourg, where they remained for about three years. He translated books from Latin and German and wrote an important defence of Barnes. This is regarded as his most significant reforming statement apart from his Bible prefaces. He received the degree of DTh from Tübingen and visited Denmark, where he wrote reforming tracts. In Strasbourg he befriended Conrad Hubert, Martin Bucer's secretary and a preacher at the church of St Thomas. Hubert was a native of Bergzabern (now Bad Bergzabern) in the duchy of Palatine Zweibrücken. In September 1543, on the recommendation of Hubert, Coverdale became assistant minister in Bergzabern as well as schoolmaster in the town's grammar school. During this period, he opposed Martin Luther's attack on the Reformed view of the Lord's Supper. He also began to learn Hebrew, becoming competent in the language, as had been Tyndale.[2]

Return to England, 1548

[edit]

Exeter Cathedral - West Window

Edward VI (1547–53) was only 9 years old[20] when he succeeded his father on 28 January 1547. For most of his reign he was being educated, whilst his uncle, Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, acted as Lord Protector of the Realm and Governor of the King's Person. Immediately upon receiving these appointments he became Duke of Somerset.

Coverdale did not immediately return to England, although the prospects looked better for him. Religious policy followed that of the chief ministers and during Edward's reign this moved towards Protestantism. However in March 1548 he wrote to John Calvin that he was now returning, after eight years of exile for his faith. He was well received at the court of the new monarch. He became a royal chaplain in Windsor, and was appointed almoner to the queen dowager, Catherine Parr. At Parr's funeral in September 1548, Coverdale delivered what would later be said to have been his "1st Protestant sermon".[21]

On 10 June 1549, the Prayer Book Rebellion broke out in Devon and Cornwall. There, Coverdale was directly involved in preaching and pacification attempts.[2] Recognising the continuing unpopularity of the Book of Common Prayer in such areas, the Act of Uniformity had been introduced, making the Latin liturgical rites unlawful from Whitsunday 1549 onward. The west-country rebels, many of whom spoke Cornish but not English, complained that the new English liturgy was "but lyke a Christmas game" – men and women should form separate files to receive communion, reminding them of country dancing.[22]

The direct spark of rebellion occurred at Sampford Courtenay where, in attempting to enforce the orders, an altercation led to a death, with a proponent of the changes being run through with a pitchfork.[23]Unrest was said also to have been fuelled by several years of increasing social dissatisfaction.[24] Lord John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford was sent by the Lord Protector to put down the rapidly spreading rebellion and Coverdale accompanied him as chaplain.[note 14] The Battle of Sampford Courtenay effectively ended the rebellion by the end of August, at a loss of over 1,200 Catholic rebel lives,[25] and several thousands more in previous battles and massacres.

However Coverdale remained in Devon for several more months, helping to pacify the people and doing the work that properly belonged to the Bishop of Exeter. The incumbent, John Vesey, was eighty-six, and had not stirred from Sutton Coldfield in Warwickshire, his birthplace and long-term residence.

Bishop of Exeter, 1551

[edit]

Coverdale spent Easter 1551 in Oxford with the Florentine-born Augustinian reformer Peter Martyr Vermigli. At that time, Martyr was Regius Professor of divinity, belonging to Magdalen College.[9]: 1267 He had been assisting Cranmer with a revision of the Anglican prayer book.[2] Coverdale attended Martyr's lectures on the Epistle to the Romans and Martyr called him a "a good man who in former years acted as parish minister in Germany" who now "labours greatly in Devon in preaching and explaining the Scriptures". He predicted that Coverdale would become Bishop of Exeter and this took place on 14 August 1551 when John Vesey was ejected from his see.[2]

Third exile, 1553–1559

[edit]

Edward VI died of tuberculosis on 6 July 1553.[20] Shortly before, he had attempted to deter a Roman Catholic revival by switching the succession from Mary daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon to Lady Jane Grey. However his settlement of the succession lasted barely a fortnight. After a brief struggle between the opposing factions, Mary was proclaimed Queen of England on 19 July.[note 15] Historian Eamon Duffy reports that the news broke during a sermon by Bishop Coverdale, during which almost all the congregation walked out one by one (i.e., such was the anti-Protestant affinity of the locals of Devon and Cornwall.)[26]: 202

The renewed danger to reformers such as Coverdale was obvious.[2] He was summoned almost immediately to appear before the Privy Council and on 1 September he was placed under house arrest in Exeter.[note 16] On 18 September, he was ejected from his see and Vesey, now ninety and still in Warwickshire, was reinstated. Following an intervention by his brother-in-law, chaplain to King Christian III of Denmark-Norway, Coverdale and his wife were permitted to leave for that country. They then went on to Wesel, and finally back to Bergzabern.

On 24 October 1558, Coverdale received leave to settle in Geneva.[27][2] Commenting on his contribution to the Geneva Bible (the exact details of which are scarce), Daniell says: "Although his Hebrew, and ... now his Greek, could not match the local scholars' skills, Coverdale would no doubt have special things to offer as one who nearly two dozen years before had first translated the whole Bible ... the only Englishman to have done so, and then revised it under royal authority for the successive editions of the Great Bible." On 29 November 1558 Coverdale was godfather to John Knox's son. On 16 December he became an elder of the English church in Geneva, and participated in a reconciling letter from its leaders to other English churches on the continent.[_citation needed_]

In August 1559, Coverdale and his family returned to London, where they lodged with the Duchess of Suffolk, whom they had known at Wesel.[2] He was appointed as preacher and tutor to her children. He wrote to William Cole in Geneva, saying that the duchess had "like us, the greatest abhorrence of the ceremonies" (meaning the increasing reversion to the use of vestments).[note 17]

His stance on vestments was one of the reasons why he was not reinstated to his bishopric. However Hughes believes that it is likely that in his own opinion, he felt too elderly to undertake the responsibility properly.[7] From 1564 to 1566, he was rector of St Magnus the Martyr in the City of London near London Bridge. Coverdale’s first wife, Elizabeth, died early in September 1565, and was buried in St Michael Paternoster Royal, City of London, on the 8th. On 7 April 1566 he married his second wife, Katherine, at the same church.[2] After the summer of 1566, when he had resigned his last living at St Magnus, Coverdale became popular in early Puritan circles, because of his quiet but firm stance against ceremonies and elaborate clerical dress.[7] Due to his opposition to official church practices, he died in poverty aged 80 or 81 on 20 January 1569, in London and was buried at St Bartholomew-by-the-Exchange with a multitude of mourners present.[28] When that church was demolished in 1840 to make way for the new Royal Exchange, his remains were moved to St Magnus, where there is a tablet in his memory on the east wall, close to the altar.[2] Coverdale left no will and on 23 January 1569 letters of administration were granted to his second wife, Katherine. Daniell says that it appears that he has no living descendants.[_citation needed_]

Coverdale's legacy has been far-reaching, especially that of his first complete English Bible of 1535. For the 400th anniversary of the Authorised King James Bible, in 2011, the Church of England issued a resolution, which was endorsed by the General Synod.[29] Starting with the Coverdale Bible, the text included a brief description of the continuing significance of the Authorised King James Bible (1611) and its immediate antecedents:

- The Coverdale Bible (1535)

- The Matthew Bible (1537)

- The Great Bible (1539)

- The Geneva Bible (1557, the New Testament; 1560, the whole Bible)

- The Bishops' Bible (1568)

- The Rheims-Douai Bible (1582, the New Testament; 1609–1610, the whole Bible)

- The Authorised King James Bible (1611)

As indicated above, Coverdale was involved with the first four of the above. He was partially responsible for Matthew's Bible.[2][note 18] In addition to those mentioned above, he produced a diglot New Testament in 1538.[7]: 101 He was extensively involved with editing and producing the Great Bible. He was also part of the group of "Geneva Exiles" who produced the Geneva Bible[2] – the edition preferred, some ninety-five years later, by Oliver Cromwell's army and Parliamentarians.

Fragment of Miles Coverdale's Goostly Psalmes and Spirituall Songes in the Bodleian Library, Oxford

Coverdale's translation of the Psalms (based on Luther's version and the Latin Vulgate) have a particular importance in the history of the English Bible.[30] His translation is still used in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.[9] It is the most familiar translation for many in the Anglican Communion worldwide, particularly those in collegiate and cathedral churches.[31] Many musical settings of the psalms also make use of the Coverdale translation. For example Coverdale's renderings are used in Handel's Messiah, based on the Prayer Book Psalter rather than the King James Bible version. His translation of the Roman Canon is still used in some Anglican and Anglican Use Roman Catholic churches. Less well known is Coverdale’s early involvement in hymn books. Celia Hughes believes that in the days of renewed biblical suppression after 1543, the most important work of Coverdale, apart from his principal Bible translation, was his Ghostly Psalms and Spiritual Songs .[7] This she calls "the first English hymn book" and "the only one until the publication of the collection by Sternhold and Hopkins." (This was more than twenty years later). The undated print probably was done parallel to his Bible translation in 1535.[32] Coverdale’s first three hymns are based on the Latin Veni Creator Spiritus, preceding its other English translations such as that of 1625 by Bishop J. Cosin by more than ninety years.[note 19] However, the majority of the hymns are based on the Protestant hymnbooks from Germany, particularly Johann Walter's settings of Martin Luther's hymns such as Ein feste Burg. Coverdale intended his "godly songs" for "our young men ... and our women spinning at the wheels." Thus Hughes argues that he realised that for the less-privileged, his scriptural teaching could be learnt and retained more readily by song rather than by direct access to the Bible, which could often be prohibited. However, his hymnbook also ended up on the list of forbidden books in 1539, and only one complete copy of it survives which is today held in Queen's College, Oxford.[1] Two fragments survived as binding material and are now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and in the Beinecke Library at Yale.[_citation needed_]

Miles Coverdale was a man who was loved all his life for that ‘singular uprightness’ recorded on his tomb. He was always in demand as a preacher of the gospel. He was an assiduous bishop. He pressed forward with great work in the face of the complexities and adversities produced by official policies. His gift to posterity has been from his scholarship as a translator; from his steadily developing sense of English rhythms, spoken and sung; and from his incalculable shaping of the nation's moral and religious sense through the reading aloud in every parish from his ‘Bible of the largest size’.

David Daniell, ‘Coverdale, Miles (1488–1569)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, October 2009 accessed 15 February 2015.

Coverdale is honoured, together with William Tyndale, with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on 6 October. His extensive contacts with English and Continental Reformers was integral to the development of successive versions of the Bible in the English language.[_citation needed_]

- Remains of Myles Coverdale: Containing Prologues to the Translation of the Bible, Treatise on Death, Hope of the Faithful, Exhortation to the Carrying of Christ's Cross, Exposition Upon the Twenty-Second Psalm, Confutation of the Treatise of John Standish, Defence of a Certain Poor Christian Man, Letters, Ghostly Psalms and Spiritual Songs. (1846)

- Writings and Translations of Myles Coverdale: The Old Faith, A Spiritual and Most Precious Pearl, Fruitful Lessons, A Treatise on the Lord's Supper, Order of the Church in Denmark, Abridgment of the Enchiridion of Erasmus (1844)

- Memorials Of The Right Reverend Father In God Myles Coverdale, Sometime Lord Bishop Of Exeter; Who First Translated The Whole Bible Into English: Together With Divers Matters Relating To The Promulgation Of The Bible, In The Reign Of Henry The Eighth (1838)

- The Letters Of The Martyrs: Collected And Published In 1564 With A Preface By Miles Coverdale (1838)

- Psalms

- Timeline of the English Reformation

- Censorship of the Bible § England

^ According to a bronze plaque on the wall of the former York Minster library, he was believed to have been born in York circa 1488. Anon. (4 September 2014). "Bronze commemorative plaque on wall of former York Minster Library". Retrieved 15 February 2015. However, the exact birth location of York does not appear to be corroborated. An older source (Berkshire History – based on Article of 1903) even suggests his birthplace as Coverdale, a hamlet in North Yorkshire, but neither is this elsewhere substantiated. Daniell says that no details are known of his parentage or early education, so simply Yorkshire is the safest conclusion.

^ Daniell states "BCL according to Cooper, BTh according to Foxe." At the time, such students had to gain proficiency in both subjects.

^ But Trueman also says that Barnes was incorporated BTh in Cambridge university in 1522-3, followed in 1523 by the award of a DTh., so Barnes' return from Louvain was probably in about 1522.

^ Hughes cites four twentieth century authors in support of this view, having said that some older biographers discount the suggestion. Daniell states firmly that Coverdale and Rodgers were with Tyndale in Antwerp in 1534, whilst discounting the account of Foxe (1563) that Coverdale travelled to Hamburg to assist Tyndale in planned printing work.

^ The colophon of the bible itself states this exact date.

^ "Knowing neither Hebrew nor Greek, Coverdale consulted Latin (Vulgate and Pagninus’ Latin version of 1528), English (translations associated with Tyndale), German (Luther’s translation) and Swiss (Zurich Bible of 1531 and 1534) sources to guide him on those portions of the Old Testament that Tyndale had not finished (Matthew’s Bible, Introduction, ix) and to adapt those portions of the Old Testament that Tyndale had finished as well as the Tyndale New Testament of 1526."[11]

^ In his dedication to King Henry, Coverdale explains that he has ‘with a clear conscience purely and faithfully translated this out of five sundry interpreters’. Daniell explains that this means Tyndale, Luther, the Vulgate, the Zürich Bible, and Pagninus's Latin translation of the Hebrew.

^ The following is Guido Latré's citation for: ... it was Coverdale's glory to produce the first printed English Bible, and to leave to posterity a permanent memorial of his genius in that most musical version of the Psalter which passed into the Book of Common Prayer, and has endeared itself to generations of Englishmen. Darlow,T.H. & Moule,H.F., Historical Catalogue of the printed Editions of Holy Scripture in the Library of the British and Foreign Bible Society, 2 vols., London and New York, 1963 (1st ed. 1903) p.6

^ The description ‘Great Bible’ is justified, since it measured 337 mm by 235 mm.

^ A further detail, possibly apocryphal, is that additional sheets were re-purchased as waste paper from a tradesman to whom they had been sold. Foxe (1563) wrote that they had been proffered as hat linings

^ A special copy on vellum, with illuminations, was prepared for Cromwell himself, and is now in the library of St. John’s College, Cambridge.

^ General Note (by Bodleian Library): English and Latin in parallel columns; the calendar is printed partly in red; this edition repudiated by Coverdale on account of the faulty printing.

^ Rychard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch finally printed the London large folio edition of the Great Bible in 1539. Coverdale compiled it, based largely on the 1537 Matthew’s Bible, which had been printed in Antwerp from translations by Tyndale and Coverdale.

^ A later writer recalled that ‘none of the clergy were ready to risk life with Russell's expedition but old Father Coverdale’ (A Brieff Discours, cited by Daniell, p. 232). On the field at Woodbury Windmill, Coverdale ‘caused general thanksgiving to be made unto God’ (Mozley – see Daniell, 15).

^ Her reign was dated from 24 July.

^ In November 1553 and April 1554 both Peter Martyr and the king of Denmark refer to him as having been a prisoner.

^ Daniell cites Mozley, 23, in support of this detail, which is useful in illustrating how, by that time, Coverdale's theology had developed beyond the accepted mainstream of the Elizabethan reforms.

^ According to Daniell, the second half of the Old Testament of the Matthew's Bible was Coverdale's translation.

^ Still used as Hymn No. 153 of the English Hymnal – "Come Holy Ghost, our souls inspire, ..." (NEH No. 138) with English words by Bishop Cosin, music by Thomas Tallis. See The English Hymnal – With Tunes, First ed. Ralph Vaughan Williams, London: Oxford University Press, 1906.

^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Daniell, David (2004). "Coverdale, Miles (1488–1569)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6486. Retrieved 17 February 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

^ Anon. "Early Printed Bibles – in English – 1535–1610". British Library – Help for Researchers – Coverdale Bible. The British Library Board. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

^ a b c d Trueman, Carl R. (2004). "Barnes, Robert (c.1495–1540)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1472. Retrieved 1 April 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

^ Salzman, L.F. (ed.). "'Friaries: Austin friars, Cambridge.' A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 2 pp287-290". British History online. London: Victoria County History, 1948. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

^ a b c Duffy, Eamon. (1992). The Stripping of the Altars. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05342-8.

^ a b c d e Hughes, Celia (1982). "Coverdale's alter ego" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 65 (1). Manchester, UK: John Rylands University Library: 100–124. ISSN 0301-102X. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

^ Daniell, David (2004). "Tyndale, William (c.1494–1536)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27947. Retrieved 11 April 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

^ a b c d Cross 1st ed., F.L.; Livingstone 3rd. ed., E.A. (2006). Article title: Bible, English versions The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211655-X. CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

^ Latré, Guido. "The Place of Printing of the Coverdale Bible". Tyndale org. K. U. Leuven and Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium, 2000. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

^ Naudé, Jacobus A. (13 September 2022). "Emergence of the Tyndale–King James Version tradition in English Bible translation". HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies. 78 (1). doi:10.4102/hts.v78i1.7649.

^ a b c Kenyon, Sir Frederic G. "The Great Bible (1539–1541) – from Dictionary of the Bible". Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1909. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

^ Anon. "English Short Title Catalogue – New Testament, Latin, Coverdale, 1538. Original title – The New Testamen [sic] both in Latin and English after the vulgare texte, which is red in the churche translated and corrected by Myles Couerdale". British Library. British Library Board – Original publishers: Paris :Fraunces Regnault ..., prynted for Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch cytezens of London, M.ccccc.xxxviii [1538] in Nouembre. Cum gratia & priuilegio regis. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

^ Coverdale, Myles. "The newe testamente [electronic resource] : both Latine and Englyshe ech correspondent to the other after the vulgare texte, communely called S. Ieroms. Faythfully translated by Myles Couerdale. Anno. M.CCCCC.XXXVIII. Coverdale, Miles". SOLO – Search Oxford Libraries Online. Printed in Southwarke : By Iames Nicholson. Set forth wyth the Kynges moost gracious licence, 1538. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

^ a b Leithead, Howard (2004). "Oxford DNB Article: Cromwell,Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6769. Retrieved 5 March 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

^ Rex, Richard, "The Crisis of Obedience: God’s Word and Henry’s Reformation", The Historical Journal, V. 39, no. 4, December 1996, pp. 893–4.

^ King, Richard John. "Berkshire History: Biographies: Miles Coverdale (1488–1569)". Berkshire History. David Nash Ford. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

^ Anon. "English Short Title Catalogue – Full View of Record – Uniform title – English Great Bible". British Library. British Library Board – Original publisher Rychard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch, Cum priuilegio ad imprimendum solum, April 1539. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

^ Ditchfield, P H; Page, W. "'Parishes: Bucklebury.' A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3, pp291 – 296". British History Online. London: Victoria County History, 1923. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

^ a b Cannon, John (2009). A Dictionary of British History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191726514. (entry Edward VI).

^ Murray, John (1872). A Handbook for Travellers in Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire. Gloucestershire: J Murray. pp. 162–163.

^ Eamon Duffy, The voices of Morebath: reformation and rebellion in an English village, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, p. 133.

^ The Church of England – A Christian presence in every community. "A Church Near You". St Andrew, Sampford Courtenay. © 2015 Archbishops' Council. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

^ Somerset to Sir Philip Hobby, 24 August 1549. In: Gilbert Burnet, The history of the Reformation of the Church of England, ed. Nicholas Pocock, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1865, vol. V., pp. 250–151. Cited in: Roger B. Manning, "Violence and social conflict in mid-Tudor rebellions," Journal of British Studies, vol. 16, 1977, pp. 18–40 (here p. 28)

^ Philip Payton. (1996). Cornwall. Fowey: Alexander Associates

^ Duffy, Eamon (2001). The voices of Morebath: reformation and rebellion in an English village. New Haven London: Yale university press. ISBN 0300091850.

^ Daniell, David (2004). "Coverdale, Miles (1488–1569), Bible translator and bishop of Exeter". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6486. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

^ Bobrick, Benson. (2001). Wide as the Waters: the story of the English Bible and the revolution it inspired. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84747-7. p. 180.

^ Anon. "Diocesan Synod Motion – Confidence in The Bible – 11/04/2011" (PDF). Church of England. Church of England General Synod. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

^ Marlowe, Michael D. "Coverdale's Psalms". Bible Research – Internet Resources for Students of Scripture Online since February 2001. Michael D. Marlowe, 2001 – 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

^ Peterson W S and Macys V. "Psalms – The Coverdale translation" (PDF). Little Gidding: English Spiritual Traditions – 2000. Authors. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

^ Leaver, Robin A. (1982). "A Newly-Discovered Fragment of Coverdale's Goostly Psalmes". Jahrbuch für Liturgik und Hymnologie. 26: 130–150.

- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1887). "Coverdale, Miles" . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). "Coverdale, Miles" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 343–344.

- Coverdale Bible online

- Myles Coverdale at Find a Grave

- Royal Berkshire History: Miles Coverdale (1488–1569)

- Works by Myles Coverdale at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Works by Myles Coverdale at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| Religious titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byJohn Vesey | Bishop of Exeter 1551–1553 | Succeeded byJohn Vesey |