Morse v. Frederick (2007) (original) (raw)

Home » Articles » Case » Qualified Immunity » Morse v. Frederick (2007)

Written by

, published on August 6, 2023 last updated on July 2, 2024

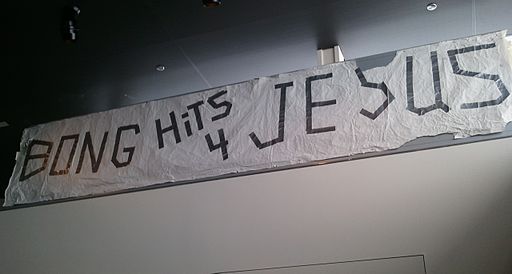

The original "Bong Hits for Jesus" banner that led to a Supreme Court decision on student speech now hangs in the Newseum Institute in Washington, DC. In the case, an 18-year-old Alaska student's unfurling of the sign on a public street near his school led to his suspension. The Supreme Court held that a school could censor student speech that they believe encourages illegal drug use. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

In Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007), often referred to as the “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” case, the Supreme Court ruled that it is not a denial of the First Amendment right to free speech for public school officials to censor student speech that they reasonably believe encourages illegal drug use.

Frederick suspended for unveiling banner referencing drug use

The case began in January 2002 when Joseph Frederick, an 18-year-old student at Juneau-Douglas High School in Alaska, unfurled a 14-foot banner with the message “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” as the Winter Olympics torch relay passed by a public street near his school. Frederick had skipped school that day, intent on displaying his message before television cameras. Frederick, who stood off-campus with several others with his banner, claimed he picked this message not for any commentary on drugs or religion, but simply as a First Amendment experiment to test his free speech rights.

School principal Deborah Morse grabbed the banner and ordered Frederick to her office. She initially suspended him for five days. After Frederick quoted Thomas Jefferson’s “speech limited is speech lost,” she doubled his suspension period.

Frederick, then Morse appealed court decisions

Frederick administratively appealed his suspension to no avail. He then filed suit in federal court, contending Morse had violated his First Amendment rights. A federal district court dismissed the suit, reasoning Morse had the authority to punish Frederick for his message that she reasonably interpreted “directly contravened the Board’s policies related to drug abuse prevention.”

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed, finding that Morse violated Frederick’s First Amendment rights when she punished him based on the content of his speech without showing that his expression would cause any type of disruption. According to the Ninth Circuit, her actions violated the principles of the Supreme Court’s landmark studentspeech precedent, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969). The Ninth Circuit also ruled that Morse was not entitled to qualified immunity because it was clearly established that Frederick had a First Amendment right to display his banner.

Morse and the school board appealed to the Supreme Court with the free legal assistance of former federal appeals court judge and independent counsel Kenneth Starr. Morse argued that the Ninth Circuit strayed from the Court’s later student-speech decision of Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) and Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988). The Supreme Court ruled that Morse did not violate Joseph Frederick’s First Amendment rights.

In this photo, Luke Remchuk, of Bethesda, Maryland, left, Kevin Newcomb, of Bethesda, Maryland, center, and Jay Hartman, of Adelphi, Maryland, right, protest for students free speech outside the Supreme Court in Washington, Monday, March 19, 2007. They were protesting during the case Morse v. Frederick (2007), in which the Supreme Court ruled that it is not a denial of the First Amendment right to free speech for public school officials to censor student speech that they reasonably believe encourages illegal drug use. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Court ruled that school officials can prevent students from advocating drug use

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. reasoned that school officials have the power to prevent students from advocating drug use, stating that “schools may take steps to safeguard those entrusted to their care from speech that can reasonably be regarded as encouraging illegal drug use.”

Roberts first dismissed the argument that the case was not a student speech case at all. He noted that the torch relay was an “approved social event” at which many students participated. “There is some uncertainty at the outer boundaries as to when courts should apply school-speech precedents, but not on these facts,” he wrote.

Roberts then created an exception to the Tinker standard for speech that celebrates illegal drug use, which, he wrote, “poses a particular challenge for school officials working to protect those entrusted to their care from the dangers of drug abuse.”

Roberts did reject the school officials’ arguments that the Kuhlmeier school-sponsored student-speech precedent controlled the analysis because Frederick’s banner was not school sponsored. He also rejected the argument that the Fraser precedent enabled school officials to prohibit any student expression they find “plainly offensive,” stating, “After all much political and religious speech might be perceived as offensive to some.”

Dissenters said majority sanctioned viewpoint discrimination

Justice John Paul Stevens—joined by Justices David H. Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg—dissented on the underlying First Amendment question. He wrote that “the Court does serious violence to the First Amendment in upholding—even, lauding—a school’s decision to punish Frederick for expressing a view with which it disagreed.” According to Stevens, the majority sanctioned “stark viewpoint discrimination.” Stevens did agree with the majority that Principal Morse should be entitled to qualified immunity.

Concurring opinions discussed political issue speech and rights of students

Justice Samuel A. Alito, joined by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, wrote a concurring opinion, which joined the majority on the understanding that “it goes no further than to hold that a public school may restrict speech that a reasonable observer would interpret as advocating illegal drug use” and would not restrict student speech about a legitimate political issue, such as the legalization of marijuana for medicinal purposes.

Justice Clarence Thomas also concurred, emphasizing his continued commitment to originalism, and calling for the Court’s decision in Tinker to be overruled. Thomas reasoned that “the history of public education suggests that the First Amendment, originally understood, does not protect student speech in public schools.”

Justice Stephen G. Breyer concurred in part, reasoning that the Court should not resolve the underlying First Amendment issue but simply rule for Principal Morse on qualified immunity grounds.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.