General Educational Recommendations for Students with Fragile X Syndrome | NFXF (original) (raw)

-

- Fragile X 101

* Fragile X 101

* Prevalence

* Signs and Symptoms

* Genetics and Inheritance

* Testing and Diagnosis - Fragile X Syndrome

* Fragile X Syndrome

* Newly Diagnosed

* Fragile X & Autism - Associated Conditions

* Premutation

* FXPOI

* FXTAS

* New Developments - Xtraordinary Individuals

- 31 Shareable Fragile X Facts

- Fragile X Info SeriesFact sheets by topic

- Fragile X MasterClass™️

- Knowledge CenterFrequently asked questions.

- Fragile X 101

-

- Resources for Families

- FXS Strategies by Topic

* Adulthood

* Autism

* Behavior

* COVID-19

* Daily Living

* Females

* Medications

* Physical & Medical Concerns

* Puberty & Sexuality

* School & Education - FXS Resources by Age

- Premutation Topics

* The Fragile X Premutation

* FXTAS Resources

* FXPOI Resources

* Reproductive Resources - Newly Diagnosed

- ResearchLearn and participate

* Research 101What is research?

* STX209 Reconsent ProjectEnrollment is open

* International Fragile X Premutation Registry — For ParticipantsEnroll now

* Participate in ResearchMyFXResearch Portal

* Original Research Articles

* FORWARD-MARCHDatabase and registry

* Research ResultsNew and archives - Find a Fragile X Clinic

* U.S. Fragile X Syndrome Clinics

* FXTAS-Specific Clinics

* International Clinics & Organizations - Find a Contact Near You

- Knowledge CenterOur Fragile X library

- Webinars & Videos

- Printable Resources

- Treatment Recommendations

-

- Resources for Professionals

- NFXF MasterClass™️ for Professionals

- Research Readiness ProgramResearch facilitation for researchers

- NFXF Data Repository

- International Fragile X Premutation Registry — Research Requests

- FORWARD-MARCHRegistry & Database

- NFXF-Led PFDD Meeting for Fragile X SyndromePatient-focused drug development

- Marketing Your Research Opportunities

- Treatment Recommendations

- Fragile X Clinics

* U.S. FXS Clinics

* FXTAS-Specific Clinics

* International Clinics & Organizations - NFXF RESEARCH AWARDS

* Randi J. Hagerman Summer Scholar Research Awards

* Junior Investigator Awards

Get

Involved-

- Fragile X 101

* Fragile X 101

* Prevalence

* Signs & Symptoms

* Genetics and Inheritance

* Testing and Diagnosis - Fragile X Syndrome

* Fragile X Syndrome

* Fragile X & Autism - Associated Conditions

* Premutation

* FXPOI

* FXTAS

* New Developments - Xtraordinary Individuals

- 31 Shareable Fragile X Facts

- Fragile X Info Series

- FRAGILE X MASTERCLASS

- Knowledge Center

- Fragile X 101

-

- Resources for Families

- FXS Strategies by Topic

* Adulthood

* Autism

* Behavior

* Daily Living

* Females

* Medications

* Physical & Medical Concerns

* Fragile X and Puberty & Sexuality

* School & Education - FXS Resources by Age

- Premutation Topics

* The Fragile X Premutation

* FXTAS Resources

* FXPOI Resources

* Reproductive Resources - Newly Diagnosed

- Research

* Research 101: What is Research?

* STX209 Reconsent Project

* International Fragile X Premutation Registry — For Participants

* Participate in Research

* Original Research Articles

* FORWARD-MARCH

* Research Results Roundup - Find a Clinic Near You

- Find a Contact Near Your

- Knowledge Center

- Webinars & Videos

- Printable Resources

- Treatment Recommendations

-

- Resources for Professionals

- NFXF MasterClass™️ for Professionals

- Research Readiness Program

- NFXF Data Repository

- International Fragile X Premutation Registry — Research Requests

- FORWARD-MARCH Registry & Database

- NFXF-Led Patient-Focused Drug Development Meeting

- Marketing Your Research Opportunities

- Treatment Recommendations

- Find a Clinic Near You

- NFXF Research Awards

* Randi J. Hagerman Summer Scholars

* Junior Investigator Awards

General Educational Recommendations for Students with Fragile X Syndrome

General Educational Recommendations for Students with Fragile X SyndromeDan Whiting2023-05-01T21:05:35-04:00

Consensus of the Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium

General Educational Recommendations for Students with Fragile X Syndrome

Reading Time: 38 min.—**|—Last Updated:** Oct. 2018—**|—First Published:** Aug. 2012—**|**—Download PDF

- Response to Intervention

- Multi-Tiered System of Supports

- Inclusion

- The Individualized Education Plan

- Educational Strategies for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome

- Early Intervention

- Early Childhood

- Middle and High School

- Elementary School

- Post-Secondary

- Descriptions of Assessments

- School Services

- IEP Checklist

- References and Author Note

The relationship between the family and the school is central to the educational success of the child with Fragile X syndrome (FXS). This relationship will last for years and will span the formative years of the child’s life. As such it is very important for all involved to understand the legal aspects as well as some of the nuanced practices for successfully navigating this complex system. It is important to note that in the majority of cases the system works well and both the child and their family are appropriately served. Unfortunately, however, there are cases in which additional resources and legal interventions are required in order to ensure that the child’s needs are being met.

The following document provides a basic framework for understanding different aspects of the educational system and an overview of the terminology.

Education is filled with acronyms and as such this can serve as a resource for those outside the field. It is also important to note that practices and approaches differ depending on the state in which the child resides. Some states utilize a local control approach, which means that each district or BOCES (pronounced bo-sees), or Boards of Cooperative Educational Services, is allowed to make their own policies and interpretations of federal law. As such there can be quite a bit of variability in approach from one state to another and from one school to another.

The information in this document is based on federal law, specifically IDEA, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which provides for a free, appropriate, individualized education in the least restrictive environment, for children birth through age 21 (or older if they are still attending high school). Least restrictive means that the child spends as much time with their typically developing peers as possible while meeting their goals.

For individuals with Fragile X syndrome, a variety of services and programs are available. This recommendation provides an overview of the regulatory aspects of the process as well as intervention suggestions and strategies. Age-specific recommendations and resources are available in the other recommendations documents.

Response to Intervention (RTI)

One of the most significant shifts in education policy in the past several decades has been the implementation of response to intervention or RTI. The reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA; P.L. 108-446) allows educators to use the child’s responsiveness-to-intervention as a substitute for the IQ-achievement discrepancy to identify students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) (Fuchs and Fuchs, 2005).

Although males with FXS typically do not qualify for special education with a diagnosis of SLD, this law is very important for females. This law does not require children to fail prior to receiving support in school. Rather, students are provided with targeted interventions to address academic and behavioral needs. The student’s response to these interventions is monitored closely over time.

If the student fails to respond to the interventions, teachers and related support personnel are charged to provide more frequent or intense interventions as necessary. This may include special education services with an educational diagnosis of SLD. RTI is applied in a variety of forms across the country. Although initially developed for assessment and diagnostic purposes, RTI has intervention and behavioral applications for all students. The use of a tiered approach requires significant data collection and can allow for the creation and implementation of effective interventions for children with FXS.

Since its inception in 2004, the application of RTI has broadened across the country and now is primarily used in a holistic manner and is broadly termed a Multi-Tiered System of Support or MTSS.

Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS)

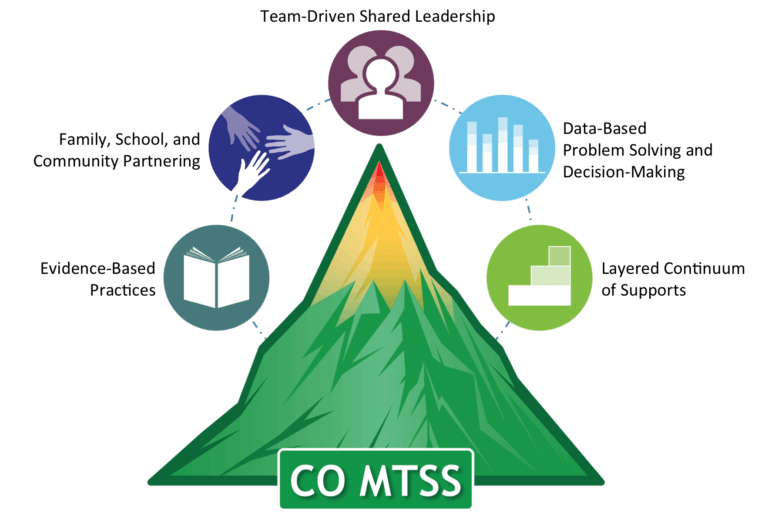

The Colorado Department of Education defines MTSS as “A Multi-Tiered System of Supports” which is a whole-school, prevention-based framework for improving learning outcomes for every student through a layered continuum of evidence-based practices” (Evolution of RTI in Colorado Fact Sheet, January 2014). Most states and schools in the United States have adopted a multi-tiered model of service delivery. MTSS uses a three-tiered model to provide differentiated support to best meet the individual needs of each child. Tier 1 services provide universal support to all students within schools. Tier 2 services target groups of students who require additional support to meet grade-level expectations. Finally, Tier 3 services provide the most individualized support to students with the highest support needs. The goal of MTSS is to optimize school outcomes for all students with a layered approach to support (Stoiber, 2014). Students with FXS may receive services at all three levels of MTSS. It also features structures for educational and behavioral challenges including but not limited to positive behavioral supports.

The graphic (Stoiber, 2014) below illustrates the primary components of MTSS.

Current applications of this tiered approach often immediately place children with genetic disorders in tier three at the top of the RTI pyramid, and in some cases outside of the system. Although this practice is theoretically correct as these children qualify for services, it limits the utility of the approach. Unilaterally placing any student at the top of the pyramid due to their diagnosis operationally assumes that they are unable to benefit from the interventions and approaches afforded to other students in tier 1 or tier 2. This concept is pivotal to effective inclusion practices. Inclusive practices, for preschoolers as well as their school-age peers, extol the benefit of best practices for children with special needs. As a result, it is important for children with FXS to be included in the RTI process whenever possible. This serves many purposes: it operationalizes the idea that children with FXS can and do benefit from universal practices, it provides a structure for them to engage in tier 2 practices that might not otherwise be considered for these children, and it provides the progress monitoring structure necessary to document effective educational interventions.

Inclusion

The momentum to include students with FXS in the general education mainstream grew out of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The assertion that children with disabilities had a civil right to attend school in their home school setting grew out of Civil Rights litigation. The emphasis to include students with FXS in general education classrooms has been noted throughout the literature. Perhaps the impetus for this movement comes from the fact that children with FXS have a considerable interest in people. One of the hallmarks of this population is a strong desire to interact socially, which makes inclusion more viable and increases the success rate.

It is important to remember, however, that placement options must include enough flexibility to meet individual needs. There are occasions when inclusion can be restrictive to children with severe needs. Successful inclusion cannot be accomplished without a systematic, sequential process. Simply placing the student with FXS in a general education classroom without adequate support systems does not necessarily constitute success. These supports include but are not limited to paraprofessional support, differentiated tasks, and thoughtful and clear behavioral expectations.

Students with FXS may require different levels of inclusion over the course of their academic experience. In addition, the outcome for each grade level may change as the goals for the individual evolve. For example, during the early elementary years, the goal of inclusion may be to engage in classroom routines, participate in social activities, and engage in academic tasks.

During middle school and high school, the student may have inclusion opportunities through school-based clubs, social skills, vocational experiences, and extracurricular activities with the goal centering on social engagement and long-term vocational success (Braden, 2011).

The Individualized Education Plan (IEP)

Special Education Services are provided as a part of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004. These services typically occur in school environments with licensed teachers and an interdisciplinary team (i.e., special education teacher, speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, school psychologist).

The Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is the legal document and the process that guides the child’s educational program and services. The IEP is developed by an interdisciplinary team including teachers, parents, and other professionals based on the child’s needs. Constructed on the regulations set forth in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the plan must be revised annually (parent or school personnel may request an IEP review meeting at any time).

Critical components of the IEP include parent involvement, goals and objectives related to the child’s current development and next steps, and intentional accommodations and modifications. Accommodations are strategies used by the teacher to “level the playing field” for children with disabilities and provide equitable access to the curriculum, meaningful participation, and adequate support. Examples of accommodations may include providing a visual schedule, extra adult or peer support, or breaks for movement. Modifications are changes to the curriculum or expectations for the child, which may include simplification of tasks or altered schedules. Modifying the environment, schedule, adult support, tasks, and expectations are important for the success of children with FXS.

See the IEP Checklist at the end of this document.

Educational Strategies for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome

Profile

Students with FXS represent a broad spectrum of cognitive abilities with individual variation. Nevertheless, there is a well-documented cognitive and behavioral phenotype. Most males with FXS exhibit deficits in cognition ranging from mild to severe. Females tend to demonstrate the same patterns but with a more mild presentation. Auditory and sequential processing deficits are frequently associated with the syndrome. Additionally, most students have executive functioning skill deficits, e.g., planning, attending, sustaining effort, generating problem solving strategies, using feedback and self-monitoring.

Males with FXS may exhibit relative strengths in verbal labeling, simultaneous learning, receptive vocabulary (which is often higher than expressive), visual perception tasks, imitation, and activities of daily living. Their weaknesses typically lie in higher level thinking and reasoning, complex problem solving, sequential tasks, quantitative skills, motor planning, socialization and communication.

Strengths of females with FXS include vocabulary and comprehension, short-term visual memory, reading, writing and spelling. Their weaknesses tend to include abstract thinking, understanding spatial relationships, quantitative and conversational processing, short-term auditory memory, maintaining attention and impulsive behavior. Mathematic skills are generally an area of challenge for females and males with FXS with performance in this area lower than would be expected even when accounting for IQ.

Generalized mild hypotonia and joint laxity (looseness) are seen in most children with fragile X syndrome. This has an impact on educational performance. Fine motor tasks such as handwriting are often difficult to master. It is likely that a student with fragile X syndrome will have some agree of gross and fine motor incoordination throughout his academic career and as such his education plan should emphasize compensatory skills (e.g. use of a computer as an alternative to handwriting).

Individuals with FXS also present with significant sensory processing issues. This can be a factor in the school setting across all ages, and often presents as a challenge for classroom teachers. Please see Sensory Processing and Integration Issues in Fragile X Syndrome for a detailed description of sensory processing and strategies for addressing this across settings.

Strategies

The assistive technology plan should involve programs and applications designed to enhance learning based on the specific cognitive and learning profile of the individual with FXS. Modified mice/keyboards and touch screens can be used to interface with technologies for educational purposes and to reduce motor demands, thus reducing limitations from motor dyspraxia and allowing responses more reflective of the ability of the individual with FXS. These technologies often allow content to be delivered visually capitalizing on the visual learning and visual memory strengths of those with FXS.

Key developmental challenges in school age individuals have been identified. Also see: Lesson Planning Guide: A Practical Approach for the Classroom.

Strategies for teachers that have been found to be most useful when educating children with FXS include (but are not limited to):

- To the degree possible, provide a calm and quiet classroom environment with built-in breaks and a predictable daily routine. Consistency and predictability are keys to a successful classroom, which ultimately benefits all students.

- Teach the student to request a break and provide a “safe” refuge area (be cautious not to confuse this with a timeout area.)

- Consider distractibility and anxiety issues when arranging seating for the student (e.g. avoid the middle of a group, seat the student away from doorways and a/c or heating vents.)

- Use small-group or one-to-one instruction when teaching novel tasks. This pre-teaching activity can greatly increase the long-term success for the child in the general classroom environment.

- Infuse a sensory diet, developed with an occupational therapist, into the student’s day to address the sensory processing issues.

- Give ample time for processing and alternative methods of responding.

- Simplify visually presented materials to eliminate a cluttered or excessively distracting and over stimulating.

- Use high and low technological adaptations, such as word tiles, sticky notes and the computer, for writing assignments.

- Provide a visual schedule and/or transitional object or task to prompt transitions.

- Use manipulatives, visual material paired with auditory input, videos, and models.

- Provide social skills lessons and social stories and engage typical peers to model appropriate behaviors.

- Provide completion or closure for activities and lessons.

- Capitalize on strengths in modeling, memory, simultaneous and associative learning.

- Use indirect questioning in a triad format to include a child with FXS, a typical peer, and teacher, rather than direct questioning to the child with FXS.

- Utilize “Cloze” or “fill-in” techniques for assessments to help facilitate executive function skills. This is where certain words from the text are removed and the participant is asked to replace the missing words.

- Use backward chaining—ask the student to finish the task after you begin it.

- Provide visual cues—such as visual icons, color coding, numbering, and arrows—to help organize tasks.

- Use reinforcements, such as “high fives”, rather than hugs or pats on the back (close physical contact tends to over-stimulate children with FXS).

- Introduce novel tasks interspersed with familiar tasks to hold attention and reduce anxiety.

- Avoid forcing eye contact or giving “look at me” prompts. Gaze avoidance for individuals with FXS serves as a protective and/or compensatory behavior. Recognizing this will allow both the educator as well as the student to engage socially, decreasing outburst and flight behavior due to hyper-arousal. Many students with FXS increase and initiate eye contact when they are comfortable with staff, so allow for opportunities by being available and by not forcing the eye contact.

Many of these strategies are suitable for the Specially Designed Instruction (SDI) and Accommodations section in the IEP.

Early Intervention

Early intervention is the process of identifying, assessing and providing intensive, multimodal services and support for children with developmental disabilities from birth through age three.

The portal for these services is Child Find. Each community has a Child Find agency. This is a free service to all families. The process typically begins with the Child Find team completing a multidisciplinary team evaluation in order to determine the child’s eligibility as well as the needs of the child and his or her family.

Once eligibility has been determined an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) must be created within 45 days. An IFSP is a legal document that provides family-based intervention services that may include: speech-language pathology (SLP) services, occupational therapy, physical therapy, audiology, family training, health services, respite care, service coordination, nutrition, vision services and in some cases transportation. These services are appropriate and beneficial for children with FXS. The IFSP is centered on the family and often includes goals for both the family and the child. The delivery of services can be provided at home, in the community and in preschools.

Individual developmental trajectories are common within FXS. However, speech-language and occupational therapy services are particularly important during this developmental stage. Intervention services are provided in the child’s natural environment, usually the child’s home. Although there has been a great deal of research on intervention strategies, there continues to be a paucity of evidence-based practices that are targeted to the birth to 3 age group. It is clear that infants and toddlers with FXS typically demonstrate developmental delays. It is also clear that they respond to early intervention services.

When selecting these services, it is important to utilize a family-centered approach that focuses on educating, training and supporting the child’s parents, as active parent involvement is necessary to ensure positive outcomes. Goals, therapeutic targets and implementation plans should be established with a multidisciplinary team and the family. A routines-based approach to these services is optimal because it increases the likelihood the child’s family will be able to follow the established therapeutic interventions.

Early Childhood

Children aged 3 to 5 years of age are considered to fall within the early childhood recommendations. These children may receive services from special education team members in a preschool setting designed for children with or without special needs.

For children with FXS, a structured, calm atmosphere, with a predictable routine is vital. Visual supports, and structured physical space including an area for self-calming e.g., a small tent with a bean bag chair would be suitable for many children with FXS. A setting that includes children at a variety of levels, including some at a higher functioning level, is optimal since many children with FXS model other children’s behavior.

Related services such as speech/language, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and behavioral interventions are provided through an IEP (from three to 21 years). As is the case with typically developing preschoolers it is important to have the child in a program that employs an evidence-based curriculum.

There should be appropriate student-to-teacher ratios, a highly qualified staff in a licensed physical space that is well-organized including a wide variety of materials. A routines-based approach to inclusive interventions is often optimal for young children with FXS. It is important to remember that additional therapeutic interventions are often necessary to those provided through the early intervention program, e.g., occupational and speech therapy.

Also see: Early Childhood Developmental and Educational Recommendations for Children with Fragile X Syndrome

Elementary School

The transition to elementary school is often a challenge and requires a great deal of intentional educational planning and progress monitoring to ensure that the child is being appropriately challenged and supported. Please see the document entitled Educational Guidelines for Fragile X Syndrome: Preschool Through Elementary Students for complete details on how best to serve children in this age range. During this time inclusion can become challenging and many students experience several different service options in an effort to find the most appropriate setting.

Middle and High School

With elementary school having put the basic building blocks in place, middle school teachers can focus on helping students with FXS achieve greater clarity and precision in oral and social communication. Encouraging the student to express himself independently (without fill-in assistance from peers or the teacher) helps foster confidence and appropriate risk-taking in social settings.

All academic instruction should reflect a practical, functional base, equipping students with tools they can call upon in their interactions with the larger world. These functional modalities range from consumer math skills to following written instructions for tests.

Questions regarding inclusion in regular classroom settings should take into account the invaluable social skill set gained there, as well as each student’s unique—and often highly motivated—interest in a particular subject area such as science, history and music.

As always, students do better when assignments are modified to account for learning style and cognitive deficits. Transitional planning as described in the Educational Guidelines for Fragile X Syndrome: Middle and High School Students document is central to effective planning. It is important to foster relationships that will transcend into friendships at this age. These friendships will provide good transition into High School and beyond.

As the student moves into high school the curricular focus shifts to more practical concerns of employability, social adaptability and ultimately, the capacity of the student with FXS to achieve self-satisfaction. The academic focus shifts from acquisition of skills to learning how to apply them in the larger world. Central to the community-based instructional emphasis are lessons on self-help, recreation, exercise, medication management, accessing mass transit and other resources of daily living.

Job experiences are invaluable for developing virtually every skill in the repertoire of students with FXS, including emotional maturity and the confidence that accompanies it. Whenever possible, school programs should provide a rotation of job placements so interest and competence levels can be assessed. Work Experience Studies (WES) can provide academic credit while the student gets to practice appropriate work behaviors.

When the student turns 18 and has an IEP in place through age 21, the emphasis shifts to the transition between school and independent adult living. Transition Programs are provided in high schools for those with FXS and other disabilities. Transition services under the Reauthorization of IDEA (2004) addresses skills necessary to be successful in moving from the school into the community and into the world of work. The student can access post-secondary education, vocational education, supported employment, independent living, day programs and community participation.

Post-Secondary

Following high school, individuals have two options:

- Engage in the work force at the appropriate level.

- Pursue a post-secondary academic experience.

The appropriateness of these opportunities should have been discussed as a part of the transition planning process discussed above and outlined in the Educational Guidelines for Fragile X Syndrome Middle and High School document.

It is also important to note that not all males are able to engage in these two options and as a result will need different types of supports. Limited post-secondary educational opportunities are available for individuals with FXS nationally. If the individual does not choose a post-secondary academic option after graduation or upon earning a certificate of attendance from high school, the person with FXS enters a new stage in personal development.

Although resources from public schools are no longer available after age 21, if the transition has been properly provided, the person with FXS can be supported in a work setting and services are funded through a regional center in many states. Successful employment may require reduced hours and opportunities to take breaks. Successful community employment opportunities for some FXS adults include: grocery store, food preparation, janitorial work, landscaping, cafeteria, animal care, child care and working in skilled nursing facilities, hospital, laundry, fast food restaurants, library, warehouse, freight yard, factory, department store, fire house, paper shredding, office work, mail delivery, preschool aide, coach’s helper, parking garage attendant.

Also see Transition to Adult Services for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome.

Description of Assessments

Early Childhood Assessment: Assessments for young children with FXS should be an authentic process that happens over time, with familiar caregivers, in familiar environments. There are diverse types of assessments that can be used to measure the developmental progress of children in the following developmental domains: cognition, physical & sensory motor, communication/language, and social/emotional. Information may be obtained from a variety of sources, such as parents, teachers, and other professionals (e.g., speech therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists) to understand the whole child. The assessment may include a developmental history, observational checklists, and specific or formal assessment instruments. The purpose of the assessment is to promote children’s learning and development, identify special services, and monitor progress.

Psychoeducational Assessment: These assessments are used to analyze the underlying cognitive processes that may impact a child’s educational performance. Children with FXS are often better at simultaneous processing than sequential processing; thus, instruments that assess both types of processing will provide helpful information regarding the student’s strengths and weaknesses. Educational testing is typically recommended every three years; however, the educational team may decide that further testing is not required or is more harmful than helpful. In these situations full assessment batteries are not conducted every three years. Using accommodations will enhance the validity of standardized measures by decreasing anxiety and hypersensitivity while simultaneously increasing engagement. Please see the Guidelines for Assessment for a full outline of these recommended accommodations and promising practices.

Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA): A problem-solving evaluation, typically conducted by a behavior specialist or school psychologist, designed to determine the underlying cause or function of a specific behavior. An FBA is important to conduct whenever disruptive or maladaptive behavior is occurring at school and had not been easily solved or redirected. An FBA can be used to develop a hypothesis for the function of challenging behaviors, identifying antecedent strategies, alternative/replacement behaviors and consequences that will not maintain the challenging behavior. A positive behavior support plan is often developed with data collection and analysis to assess the success of the intervention strategies. For students with FXS, the FBA is often best done with all the disciplines contributing their perspectives on what the antecedents to behavior may be and also in generating a comprehensive intervention plan that addresses the causes of behavior that may be outside of a classic ‘behavior’ frame. Please see the Behavior Consensus Document for more information.

Developmental/Multidisciplinary Assessment: This refers to the assessment of developmental progress in the following areas: cognitive, motor, sensory, language, and social emotional skills. Information should be obtained from parents, teachers, and other professionals (e.g.: speech therapists, occupational therapists, physical therapists). The assessment may include developmental history, observational checklists, in addition to standardized and norm referenced measures.

School Services

Some related services that are or that should be made available to school age children with FXS can include but are not limited to the following:

- A ssistive technology and Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Assistive technology (AT) is defined as equipment that helps the child improve his or her functional capabilities. For a child with low muscle tone, the assistive technology could be a special chair to help with positioning and posture. For a child with poor fine motor skills and difficulty with drawing and handwriting, the assistive technology could include computers, iPads or other devices for the child to type instead of writing, or dictation software to convert speech to text. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) refers to methods of communication that enhance or replace conventional forms of expression. For children with FXS who are not yet speaking, the AAC might be picture exchange communication system, manual language, a language board, or a computerized talking device. The decision and selection of the technology devices should be a team decision and reviewed periodically. The school is responsible for both the purchase of the appropriate devices and the training of personnel to use them when the device is identified as a need and a related service. The goals of learning to use and generalize language use with AT devices should be included in the IEP.

- Counseling services: School counselors work with students to improve their behavioral adjustment and self-control. Many times, the counseling or psychological services include social skills development by creating opportunities for children with FXS to be included in small groups at lunch, recess or during the school day.

- O ccupational therapy: Occupational therapists are vital components of the team for children with FXS (Scharfenaker and Stackhouse, 2012). The formal definition of the role of an occupational therapist is to design and implement “purposeful activity or interventions designed to achieve functional outcomes which promote health, prevent injury or disability and which develop, improve, sustain or restore the highest possible level of independence.” This can involve gross and fine motor skills and sensory processing and self-regulation as well as organization of behavior. In addition, OT’s can be helpful in evaluating environment and task/activities that might help support learning and performance behaviors.

- Ori e n tation and mobility services: This may include assessment, instruction, technical assistance and materials for safe travel in home and community e.g. public transportation.

- Pa r e n t counseling and training: Counselors provide information about the child’s disability and provide referrals for support groups, financial assistance and professionals outside the school system. This service does not provide direct service (therapy) to the parents but rather support for services provided to the child**.** Although not provided by the school, therapy for the parent or parents can be a very important for dealing with the unique challenges of having a child with fragile X syndrome.

- Physical therapy: Physical therapists generally focus on gross motor functioning, postural control, sitting, standing and walking**.** Physical therapy can be crucial for young children.

- Psychological services: School psychologists serve a multitude of roles that vary nationally and by district within a state. They too are part of the multidisciplinary team and often administer the individual IQ test and other measure They also consult regarding placement, academic interventions, social emotional skill development and learning profiles. They may also provide psychological counseling for children and parents as well as provide Functional Behavior Assessments (FBAs).

- Re creation: Some children require adapted physical education or recreational therapy to teach the necessary skills to engage in leisure and play, such as golf or taking a hike. For younger children, the adaptive PE may help them develop prerequisite skills to enable them to participate in group sports, such as tag and kickball.

- Re h a bili tative counseling services: For older children and adolescents, rehabilitative counselors provide assessments and advice regarding career development, vocational choices, achievement of independence and integration into the workplace and community**.**

- School health services: School nurses provide services such as the administration of medication, supervision of hearing and vision screenings**.**

- School social work services: School social workers serve many roles within a school. Some provide direct mental and behavioral support while others may focus more on systems that impact the family. Social workers may work with issues related to the child’s living situation and are uniquely qualified to coordinate community services for the child and his/her family. School social workers may also work with classmates to help them understand the disability of the child in special education (this service can also be provided by psychological and counseling services depending on the school district), create peer groups or peer buddies programs, or to conduct group or individual socialization therapy. Social workers often serve as “service brokers”; connecting children and families with community

- Speech Therapy: Speech/Language pathologists assess receptive and expressive speech and language, refer for medical assessment when necessary, and provide therapeutic services**.** They are an integral part of an interdisciplinary team. Communication issues are often at the core of behavioral challenges and as such a team approach is crucial to the success of the student with FXS.

- Tr a n sportation: IDEA requires that the schools provide transportation from door to school, with specialized equipment as needed, for children in special education.

Th e following checklist and strategies may be useful to consider when planning the educational future for the child:

IEP Checklist

- Include academic and non-academic goals (if needed). These goals are based on the needs defined in the narrative of the IEP.

- Limit the number of goals (maximum of 5 is recommended).

- Utilize strengths.

- If an augmentative communication device is provided, indicate that the equipment will be available for home use (training should be provided for parents).

- Request that all service providers be present at the IEP meeting. The attendance of a general education teacher is mandated by IDEA (including general education teacher if inclusion services are provided).

- All provided services must be included on the IEP (g.: speech therapy 30 minutes per week).

- Ask for a draft prior to the meeting.

- Double check for inconsistencies.

- Make sure to document who is responsible for both implementing the interventions, as well as who will be responsible for the progress monitoring.

- Procedural safeguards are required to be offered to parents at the time of the staffing.

- It is beneficial for parents to bring someone who can serve as their memory. These meetings can be emotional so it is beneficial to have someone there who can help remember to share the information or the data that parents feel is important and to recall aspects of the meeting that might be forgotten due to the stress of the situation.

References

Braden, Marcia. Braden on Behavior: Navigating the Road to Inclusion. The National Fragile X Foundation Quarterly, Issue 41, June 2011, http://www.fragilex.org/resources/foundation-quarterly/?id=42a

Evolution of RTI in Colorado Fact Sheet, January 2014

Fuchs, D. & Fuchs, L. (2005). Responsiveness to intervention: a blueprint for practitioners, policy makers and parents. TEACHING Exceptional Children (38), 1, 57-61.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 et seq. (2004) http://idea-b.ed.gov/explore/home.html).

National Center on Response to Intervention (NCRTI) (April 2010). Essential Components of RTI– A Closer Look at Response to Intervention. Retrieved from: http://www.rti4success.org/pdf/rtiessentialcomponents_042710.pdf

Scharfenaker, Sarah and Stackhouse, Tracy. Strategies for Day-to-Day Life (Source: Developmental FX). Posted June 29, 2012, National Fragile X Foundation website. http://www.fragilex.org/2012/support-and-resources/strategies-for-day-to-day-life/

Stoiber, K. C. (2014). A comprehensive framework for multitiered systems of support in school psychology. In P. Harrison & A. Thomas (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology: Databased and collaborative decision making (pp. 41–70). Bethesda, MD: The National Association of School Psychologists.

Author Notes

This guideline was updated by Karen Riley, PhD, Marcia Braden, PhD, Barbara Haas-Givler MEd, BCBA, Jeanine Coleman, PhD, Devadrita Talapatra, PhD and Eric Welin, MA. This guideline was originally authored by Marcia Braden, PhD, Karen Riley, PhD**,** Jessica Zoladz, MS, CGC, Susan Howell, MS, CGC, and Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, MD, PhD. It was reviewed and edited by consortium members both within and external to its Clinical Practices Committee. It has been approved by and represents the current consensus of the members of the Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium.

About the Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium

The Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium was founded in 2006 and exists to improve the delivery of clinical services to families impacted by any Fragile X-associated Disorder and to develop a research infrastructure for advancing the development and implementation of new and improved treatments. Please contact the National Fragile X Foundation for more information. (800-688-8765 or fragilex.org )

More Treatment Recommendations

Transition to Adult Services for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome

The transition from adolescence to adulthood can be challenging for many reasons. Those with Fragile X syndrome who were diagnosed early have most likely benefited from the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which provides funding for the support of those individuals in the public education systems affording educational and vocational opportunities.

An Introduction to Assessing Children with Fragile X Syndrome

Assessment of individuals with Fragile X syndrome has numerous challenges, ranging from choice and limitations of instruments to behavioral and emotional factors in the individual that may impact the testing process to scoring and interpretation. Fortunately, decades of research and clinical experience related to assessment — including recent detailed studies of the performance of several measures as outcome measures for clinical trials — have provided very useful guidance.

Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome

This document attempts to bring clarity to how the ASD diagnosis and Fragile X syndrome can overlap, and where they do not. Understanding this distinction can be particularly helpful for genetic counseling and when deciding upon the most appropriate medical, therapeutic, educational, and behavioral interventions that will increase the potential for both short-term and long-term improvements.

Behavioral Challenges in Fragile X Syndrome

Individuals with Fragile X syndrome often present with many endearing personality qualities and relative adaptive strengths in addition to challenging behaviors. While there are commonalities in behavior challenges in FXS, the intensity, frequency, and duration vary greatly and are influenced by other factors, such as their environment and medical conditions.

Educational Recommendations for Fragile X Syndrome — Early Childhood

For all children within the early childhood age range (birth to 5 years) and especially for young children with identified disabilities associated with a diagnosis, like Fragile X syndrome, inclusive, nurturing, and developmentally appropriate environments and caregiving are essential to growth and development.

Fragile X-Associated Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (FXPOI)

About 20% of women who carry a Fragile X premutation over their reproductive life span develop primary ovarian insufficiency, compared with only 1% in the general population. Women with a premutation may not experience symptoms of FXPOI; thus identifying risk factors to predict its onset is imperative for women’s health.

Genetic Counseling & Family Support

Genetic counseling for Fragile X disorders is particularly complex due to the multigenerational nature of FMR1 mutations and the variable implications for extended family members, including those who carry a pre- or full mutation.

Hyperarousal in Fragile X Syndrome

One of the characteristics of Fragile X syndrome is an impairment of control of arousal, another is a heightened sensitivity to environmental and social stimulation. Together, these factors combine to cause boys and girls with Fragile X syndrome to become aroused more easily and to a greater extent than others, and to remain in such a “hyperaroused” state for prolonged periods of time.

Physical Problems in Fragile X Syndrome (PDF)

Fragile X syndrome systemic effects are most noticeable in the cognitive behavioral domain, but multiple associated physical problems mostly related to loose connective tissue can occur.

Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

A seizure occurs either as primary excess electrical excitability in an otherwise normal brain or secondary to another disorder. In Fragile X syndrome the excess electrical excitability is most likely related to the effects of the genetic change in the Fragile X gene (FMR1) and the resultant loss or reduction of the Fragile X protein on activity in neurons.

Sleep in Children with Fragile X Syndrome (PDF)

Children with Fragile X syndrome who are reported to have higher rates of sleep disturbances typically include younger children, although sleep problems are reported at higher rates across all age groups and in those children with multiple co-occurring conditions such as ADHD, developmental delays, autism, and anxiety.

Toileting Issues in Fragile X Syndrome

While the majority of boys and girls with Fragile X syndrome will become toilet-trained, this is typically delayed anywhere from one to multiple years later than the general population.