The Carolina Abortion Fund: A lifeline for Southern women, struggles to meet demand amid state bans (original) (raw)

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — Halfway through every month, the Carolina Abortion Fund runs out of money.

The fund, which helps pay for abortions and related expenses, never has been able to aid all the people who request support. Before the Supreme Court overturned nearly 50 years of abortion rights last June, the fund turned away roughly 100 people a month. Since then, it has closed its phone lines on at least twice as many callers, and possibly many more.

Most of the hundreds of unanswered calls are from people seeking money to travel to North Carolina from states that have banned or severely restricted abortion. They are often parents of young children and living in poverty. They either have to scrounge for other ways to pay for their abortions, wait until the next month if they can, or carry their pregnancies to term.

“You can absolutely hear urgency in their voices, you hear people crying on the phone, you can’t not get emotional,” said Kristy Kelly of Charlotte, a hotline volunteer. “These are human beings with lives and this is not a piece of paper or legislation to them, this is affecting somebody’s entire life trajectory.”

The Carolina Abortion Fund is one of roughly 90 small organizations across the country that often serve as a last vestige of support for people desperate to terminate unplanned pregnancies. Though donations to these funds spiked after _Roe v. Wade_’s reversal in 2022, so did demand, as many states tightened abortion restrictions that forced people to look beyond — sometimes way beyond — their own states for abortion services.

Indeed, a full 60% of people who reach out to the Carolina Abortion Fund, or CAF, are given nothing. The vast majority of the other 40% receive just a fraction of what they need and a very small number of people receive full funding.

Monica, in a sense, was one of the lucky ones.

Just two days before the fund’s hotline shut down for the month in January, Monica got a return call from Carolina board member Omme-Salma Rahemtullah. Monica, whose name has been changed to protect her privacy, confided she was out of a job, had just left an abusive relationship and was struggling to make ends meet for her young kids.

“I just can’t do it again, I already have three and no support,” Rahemtullah recalls her saying.

Monica was about 13 weeks pregnant, too far along for a medication abortion. She had an appointment at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Asheville, N.C., the following week. But that was a 16-hour round trip from her home in a neighboring state that bans abortion except when the mother’s life is at risk. Her trip would require money for gas, lodging, food and child care.

But Monica was still hundreds of dollars short.

A flood of donations, a surge in demand

After Roe fell, most Southern states from Texas to West Virginia rapidly banned abortion. North Carolina, which permits abortion until 20 weeks gestation, became a haven for pregnant people throughout the region. Abortion seekers flooded the state, creating the largest rate of increase in abortions managed by medical providers in the country, according to the Society of Family Planning, which researches reproductive health policy and science. The organization was unable to collect data on self-managed abortions, which are conducted outside the health-care system. But separate research by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) shows they are increasing.

At a time when abortions plummeted in the United States overall — by 32,260 from July through December 2022 — they jumped by 4,730 in North Carolina, the third-highest total increase in the country, after Florida and Illinois, the society reported in April.

North Carolina Republican lawmakers introduced legislation this week that would ban abortion after 12 weeks gestation, a period of time during which the majority of abortions take place. Republicans, who have a veto-proof supermajority, are expected to bring the measure up for a vote shortly.

Like many abortion funds throughout the country, CAF also received an upsurge of contributions following the May leak of the Supreme Court’s draft opinion in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that reversed Roe. In the few days after the leak, CAF took in one-time donations of 110,000,astartlingincreasefromthe110,000, a startling increase from the 110,000,astartlingincreasefromthe235 it received during the same week one year earlier.

But the money has not kept pace with demand. While grants and individual donations to CAF increased 41% in 2022 compared to the previous year, calls soared by 400%, according to the fund’s records. On Feb. 1 of this year, the hotline received 108 calls, a new one-day record that equaled two weeks worth of calls a year earlier. The money doled out to those callers depleted the bulk of CAF’s monthly budget, the records show.

“After Roe fell, the money was pouring in,” Kelly said. “But so were the patients.”

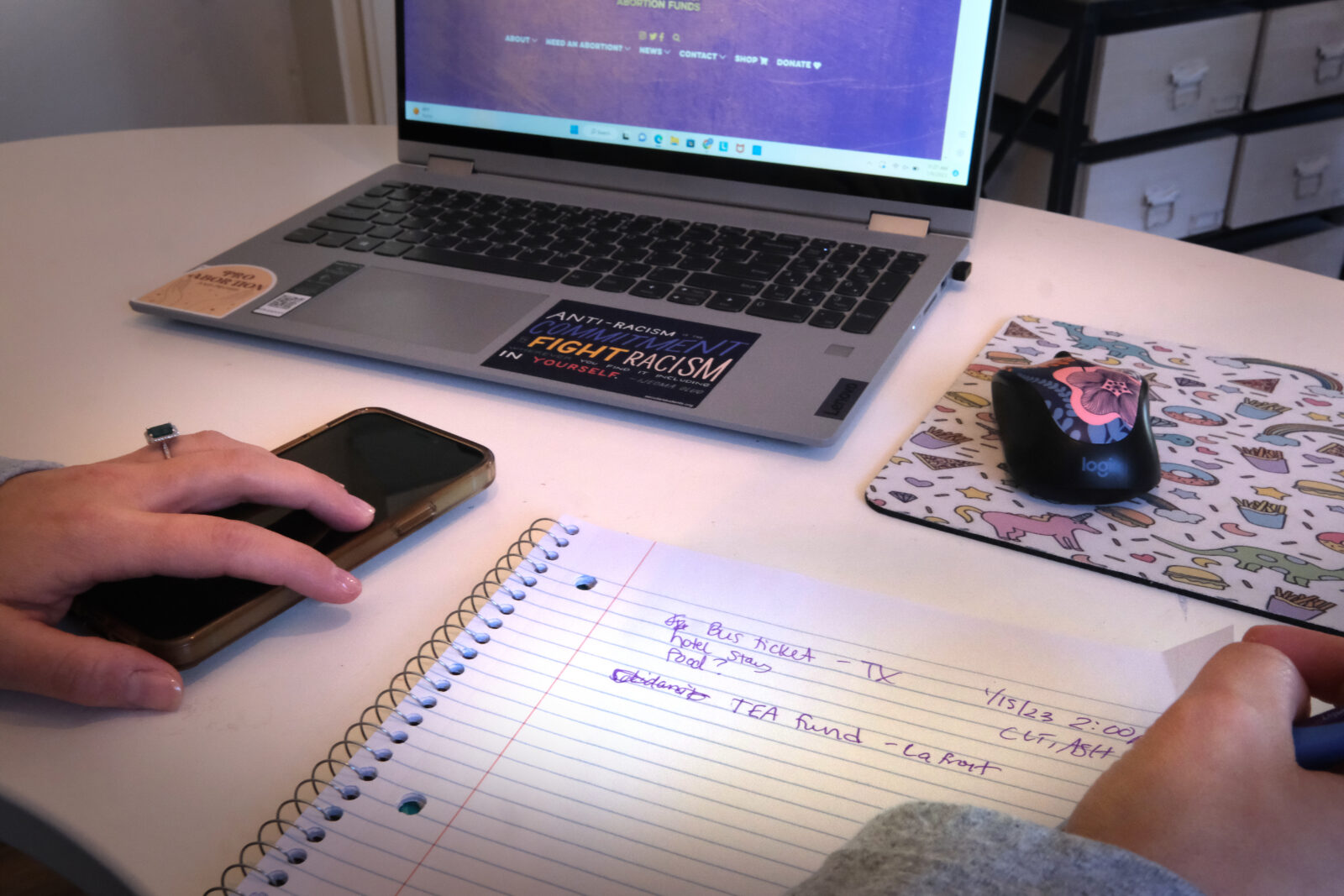

Kristy Kelly jots down details for a caller traveling from Texas to North Carolina for an upcoming abortion. In addition to the cost of an abortion, Carolina Abortion Fund’s most frequent request from callers involves help getting from their home state to North Carolina, including the cost of travel, lodging and child care. (Photo by Nancy Pierce)

What’s more, ancillary costs have skyrocketed since so many abortion seekers now are traveling to North Carolina from across the South. Even before Dobbs, Southerners were more likely than others to cross state lines to access abortion. Since Dobbs, Southerners have seen the largest increases in travel time to abortion facilities— from average drives of less than one hour to more than eight across the Deep South,according to JAMA. Most states in the South have long banned telehealth abortion, so in-person appointments are necessary even to receive abortion pills.

Most women in southern Louisiana now have to drive more than 10 hours to obtain abortions in other states, said Ushma Upadhyay, a reproductive health researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and co-author of the JAMA report. “Some have never left their state before,” she said. “They’re surviving on low incomes and can’t pay for travel, much less the overnight stay that’s needed. It’s just out of reach for many now.”

Women of color disproportionately affected

People who can’t afford to pay for abortions out of pocket generally have to piece together money to pay for the procedure or pills and travel expenses and to make up for lost wages. An abortion costs an average of 625nationally,butthatdoesn’tincludetravel,hotelstays,mealsorchildcare.Foritspart,theCarolinafundpaysanaverageof625 nationally, but that doesn’t include travel, hotel stays, meals or child care. For its part, the Carolina fund pays an average of 625nationally,butthatdoesn’tincludetravel,hotelstays,mealsorchildcare.Foritspart,theCarolinafundpaysanaverageof264 for an abortion and another 25to25 to 25to200 for other expenses. To get additional support, CAF asks its callers to reach out to other nonprofits.

Those who have the most trouble paying for abortions are disproportionately women of color, who more often than white women live in poverty in states that have banned or restricted abortion access. Access Reproductive Care-Southeast, an Atlanta-based abortion fund that serves people who live in or travel to Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina or Tennessee, reports that 81% of its callers are Black, 77% are on Medicaid or uninsured — indications of poverty — and 77% have at least one child. The Carolina fund does not keep similar statistics, but estimates that since Roe fell, half of its callers come from other states, most likely in the South.

“Even with Roe intact before bans started, there were a lot of states with plenty of citizens that wanted an abortion and could not get one because they could not afford it or because they could not travel to the location of a clinic,” said Kelly, the Carolina fund volunteer.

Nationally, three-quarters of abortion seekers have incomes below 200% of the federal poverty line**,** which is $60,000 for a family of four and less than half that for an individual, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy organization that supports abortion rights. Southern states have the largest Black population, the highest rates of poverty and the greatest number of abortions in the country — a perfect storm as legal abortion access dwindles across the region, said Rahemtullah, the Carolina fund board member.

“Roe falling is not a ban on abortion, it’s a ban on poor people getting an abortion,” she said.

The South provides more abortions, receives less money

The National Network of Abortion Funds had promised in 2020 to pour $10 million into the Carolina fund and four other funds in the mid-Atlantic region, a windfall intended to enable them to hire more staff and provide a higher level of support to callers. The funds received some of the money in 2021 and staffed up. But late last year, the national network said no more money was forthcoming because an anonymous donor reneged on its pledge.

The small abortion funds that dot America — and that provide crucial money to women in desperate straits — are often overlooked by large philanthropic organizations that funnel the bulk of their grants to larger institutions such as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the National Abortion Federation. From 2013 to 2023, small clinics and funds like the Carolina fund received just 6%, about 37million,ofthe37 million, of the 37million,ofthe575 million that foundations earmarked for abortion work, according to a Fuller Project analysis of figures from Candid, a database of nonprofit grants. The Carolina fund alone would need $6.25 million — almost one-fifth of all the grant money that went to clinics and funds in the past decade — to fully fund abortions for the 10,000 callers who contacted the hotline in 2022.

More than half of the grants — $336 million — went to the big two: Planned Parenthood’s national headquarters, which uses some of the money to help fund its clinics around the country, and the National Abortion Federation, which represents independent clinics. Both organizations put money into the Justice Fund, which helps subsidize the cost of abortions for people who can’t afford them.

The grant total doesn’t include individual donations, which shot up in the past year. There is no database of individual donors, but piecemeal information from the largest organizations shows that they are relying less on grants from foundations and more on contributions from individuals than they have in the past.

The decline in foundation giving worries advocates on the ground whose cash-strapped organizations rely on that funding. Nowhere is the concern greater than in the South, which received just 9% percent of the $575 million in grants during the past decade, despite providing more than 33% of all abortions, according to the most recent data from the Guttmacher Institute.

The 40 volunteers who take the calls for the Carolina Abortion Fund live with that reality every day, especially when callers can’t pull together the money to pay for an abortion until they have missed the window for a medication abortion. The Food and Drug Administration has approved a pill regimen — now the subject of court battles — to end a pregnancy through 10 weeks gestation. After that, women must undergo a more expensive and invasive clinical procedure.

Monica, who called the Carolina hotline just days before it shut down for the month, was able to connect with Rahemtullah, the board member. Rahemtullah pledged to give her 200fortheclinicalprocedure.SeparatelytheycalculatedthatMonicawouldneedabout200 for the clinical procedure. Separately they calculated that Monica would need about 200fortheclinicalprocedure.SeparatelytheycalculatedthatMonicawouldneedabout200 for gas — now the biggest request from callers — 100forahoteland100 for a hotel and 100forahoteland75 for child care. With some money from the Justice Fund and $150 in her own cash, Monica said she’d be covered.

“One of my underlying fears, and one that we probably all face at [the Carolina fund], is that the donations will not keep up with the ongoing needs,” said Lucy Wilson, another Carolina volunteer. “A lot of people opened their pocketbooks in the immediate days post-Dobbs. But that initial funding is not going to stick around. And I really worry about what will happen moving forward.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to make clear that when the Carolina Abortion Fund runs out of money halfway through the month, it stops doling out money to callers, but continues to refer them to other funds.