Monumental Error, by J. C. Hallman (original) (raw)

In 1899, the art critic Layton Crippen complained in the New York Times that private donors and committees had been permitted to run amok, erecting all across the city a large number of “painfully ugly monuments.” The very worst statues had been dumped in Central Park. “The sculptures go as far toward spoiling the Park as it is possible to spoil it,” he wrote. Even worse, he lamented, no organization had “power of removal” to correct the damage that was being done.

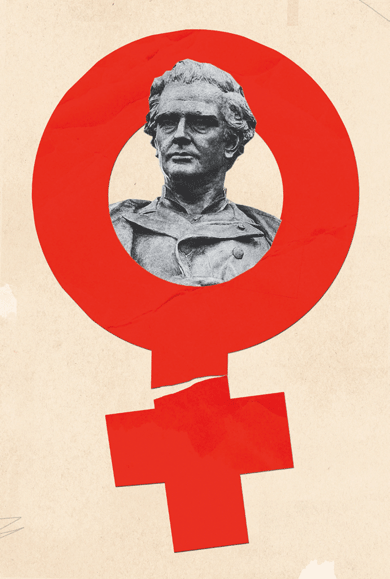

Crippen criticized more than two dozen statues for their aesthetic failures, mocking Beethoven’s frown and the epicene figure of Bertel Thorvaldsen. Yet he took pains to single out the bronze monument to J. Marion Sims, the so-called Father of Gynecology, for its foolish “combination toga-overcoat.” Would visitors really be so hurt, Crippen asked, if the Sims statue, then situated in Manhattan’s Bryant Park, was removed?

A little more than a century later — after it had been refurbished and moved to Central Park — the Sims statue has once again prompted angry calls for its removal. This time, the complaint is not that it is ugly. Rather, East Harlem residents learned that their neighborhood housed a monument to a doctor whose renown stems almost exclusively from a series of experimental surgeries that he had performed, without the use of anesthesia, on a number of young slave women between 1845 and 1849.

Illustrations by Lincoln Agnew

Sims was attempting to discover a cure for vesicovaginal fistula (VVF), a common affliction that is caused by prolonged obstructed labor. The timing, nature, and purpose of his experiments make for an impossibly tangled knot of ethical dilemmas. Most prominently, they raise the issue of medical consent. Did Sims obtain consent from his subjects, as he later claimed — and if he did, could a slave truly provide it? What woman would agree to be operated on, without anesthesia, upwards of thirty times? On the other hand, given the horrific nature of VVF, wouldn’t most women endure additional horrors in pursuit of a cure? And without a willing patient, would delicate surgery on a wound barely visible to the eye even be possible? What of the fact that if Sims managed to cure the women, they would be promptly returned to the plantations, where little awaited them but backbreaking work, use as breeders of additional slaves, and state-sanctioned rape?

All these questions came to the surface a couple of months ago, when activists long opposed to the Sims statue linked it to the Confederate war memorials being torn down in cities across America. They staged a protest in front of the statue in August, and an image from the event — four women of color in blood-soaked gowns, representing Sims’s experimental subjects — went viral. Newspaper accounts across the country soon followed. Would the monument to Sims be the very first in New York City to go to the chopping block?

That, too, is a more complicated question than it seems. What Crippen noted in 1899 is still true today. Even minor alterations to works of public art in New York City are subject to an arcane system of approval, and there is no formal mechanism in place for citizens to challenge the decisions of earlier times. The governing assumption is that if a memorial has realized permanent form, it represents a consensus that should be preserved. Not a single statue in the history of New York City has ever been permanently removed as a result of official action.1

In 1845, Marion Sims was a thirty-two-year-old doctor with ten years of experience in the South’s Black Belt. He served Alabama’s free black population; he contracted to care for the slaves of local plantation owners; and his office and home in downtown Montgomery included a small backyard facility he called the Negro Hospital. Tending to the medical needs of current and former slaves was an economic necessity in an area where two thirds of the population was black. Indeed, Sims was a slaveholder himself: he had accepted an enslaved couple as a wedding present from his in-laws, and he came to own as many as seventeen slaves before he moved to New York City in 1853. Letters to his wife (“Negroes and children always expect liberal presents on Christmas”) betray a rank paternalism typical of antebellum Southerners.

Medicine had been a default vocation rather than a calling. Sims’s mother steered him toward the cloth, his father toward the law, and the latter complained, when his son settled on medicine, that there was no “honor” or “science” in it. Sims attended medical schools in South Carolina and Philadelphia, and soon settled on surgical innovation as the best path to a lucrative practice and a permanent legacy. At the time, this involved learning new procedures from medical journals, and Sims made a name for himself by treating clubfoot and crossed eyes.

Source photographs: bust of Confederate general Stonewall Jackson © Drew Angerer/Getty Images; statue of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney © Dennis MacDonald/Alamy Stock Photo; statue of a horse in the Confederate Army © Jerry Jackson/Baltimore Sun/TNS via Getty Images

More grandiosely, he announced that he had devised a better method for dislodging foreign objects from the ear, and that he had discovered the cure for infant lockjaw. He would later apologize for the first claim, acknowledging that others had preceded him in syringing the ear. But he went to his grave insisting that his cure for lockjaw was his “first great discovery in medicine.” He couldn’t have been more wrong. Zealous in his belief that most maladies were by nature mechanical, Sims had attempted to cure a number of suffering slave babies by prying up their skull plates with an awl. Shortly after Sims died, in 1883, scientists identified lockjaw as a bacterial infection, also known as tetanus.

By Sims’s account — as related in The Story of My Life (1885), published posthumously and excerpted in this magazine — his next great discovery came just two months after the first. In the summer of 1845, he was asked to treat three young female slaves with holes inside their vaginas. A few days after delivery, fistula sufferers experience a sloughing away of dead tissue, most often leaving an opening between the vaginal canal and the bladder. Once afflicted, women are cursed with a perpetual leak of urine from their vaginas, frequently resulting in severe ulceration of the vulva and upper thighs.

These were the first cases of VVF that Sims had encountered. It’s not surprising, given his later confession that he had initially “hated investigating the organs of the female pelvis.” A little research revealed that doctors throughout history had been stymied by the affliction. The basic problem, surgically speaking, was that you had little room to see the wound you were attempting to close, let alone to stitch sutures in the secreting tissue. Sims concluded that all three of the women were untreatable, but the last, having traveled from Macon County, was permitted to spend the night in his Negro Hospital, the idea being that she would leave by train the following afternoon.

There the story might have ended — except that the next morning, Sims was called to attend to an emergency. A white seamstress had dislocated her uterus in a fall from her horse. Sims grudgingly made his way to her home and placed her facedown with her buttocks awkwardly elevated in what doctors called the knee-chest position. The idea was to vigorously push her uterus back into place. Sims was first surprised when the woman’s entire womb seemed to vanish, leaving his fingers flailing about in an apparent void — yet somehow this worked, her pain was immediately relieved. He was surprised again when the woman, lowering herself onto her side, produced a blast of air from her vagina.

The seamstress was mortified, but Sims rejoiced. The accident explained what had happened — and offered great promise besides. The position of her body and the action of his fingers against her perineum and the rear of the vaginal wall caused an inrush of air that inflated her vagina. Sims immediately thought of the young woman still waiting for a train in his backyard clinic. Might not the ballooning action of the vagina enable a doctor to clearly observe a fistula, and thereby cure a condition that had baffled the world’s leading medical minds for centuries?

Sims rushed home, stopping on the way to purchase a large pewter spoon that he believed would function more efficiently than his fingers. Two medical students assisted him with the woman — her name was either Lucy or Betsey, depending on how you read Sims’s account — and as soon as they put her in the knee-chest position and pulled open her buttocks, her vagina began to dilate with a puffing sound. Sims sat down behind her, bent the spoon, and turned it around to insert it handle first. He elevated her perineum and looked inside. He could see the fistula as plainly as a hole in a sheet of paper. Years later, Sims described the moment as if he had summited a mountain or landed on the surface of the moon.

“I saw everything,” he wrote, “as no man had ever seen before.”

This was the first of many epiphanies in a life that would come to be characterized, by Sims himself and by others after him, as having proceeded along the lines of a fantastical romance. For the next four years, the fairy tale goes, Sims labored to cure those first three slaves, along with a number of other fistula sufferers whom he sought out in neighboring communities. Progress was incremental, levying a tax on the young physician’s soul and wallet (he paid the cost of room and board for his enslaved subjects). Finally, in 1849, he managed to successfully close a fistula — and soon thereafter, he grandly claimed, he cured all the slaves in his care. At least some portion of the fame he coveted now came his way: the tool and the position he used to cure fistulas have been known ever since as the Sims speculum and the Sims position.

What followed was a period of collapse, probably from dysentery. Assuming he was gravely ill, and concerned that he “might die without the world’s reaping the benefits of my labors,” Sims published “On the Treatment of Vesico-Vaginal Fistula” in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences in 1852. The paper was an immediate success. Sims claimed that his surgery was easier to perform and produced more consistent results than had any previous techniques. Citing health reasons (Alabama colleagues thought him more ambitious than ill), he moved to New York City the next year, and soon proposed establishing Woman’s Hospital. This would be one of the first institutions in the world devoted to those conditions “of the female pelvis” that he had once deplored.

A pattern emerged. As Sims saw it, he would be presented with a series of women suffering from mysterious maladies — and, devising his own cures or improving on the cures of others, he would conquer each illness in turn. In addition to being crowned the Father of Gynecology, Sims attached his name to dozens of tools and procedures. His fame became international when he spent the Civil War years abroad, spreading the gospel of his work and tending to the medical needs of empresses and countesses. For the rest of his life, he remained a continent-hopping cosmopolite, attending conferences and practicing medicine in New York City, London, Paris, Geneva, and Vienna.

The effort to erect a monument to Sims began less than a month after his death in 1883. A Baltimore physician wrote a letter to the Medical Record, the day’s leading organ for surgeons and doctors, to suggest that a statue be commissioned and erected in Central Park.

The editor agreed. The magazine announced that it would raise the necessary funds from doctors — and from the many women who owed their health and happiness to Sims’s “amelioration of their numerous and distressing ailments.” Prominent surgeons offered pledges and praise, and suggested that a Sims Memorial Fund Committee, made up “partly of gentleman and partly of ladies,” be formed to take charge of the effort.

It was perhaps inevitable that Sims would wind up in bronze. The rhetorical mold had first been cast in 1857, by a woman named Caroline Thompson, who gave a speech to the New York state legislature after being treated by Sims. Boasting a fatality rate near zero, Woman’s Hospital was attempting to expand and become a state institution, and Thompson told legislators that a vote in favor would “build for [them] a monument in the hearts of women more durable than granite.”

The fund drive for the Central Park monument began in 1884. The Medical Record published the name of each donor and the amount of each donation, most often $1, as they came in from across the country. When sufficient funds were raised, the committee hired Ferdinand von Miller II, a German sculptor who lived in an Italian castle. He eagerly set to work, and the Sims memorial arrived in the United States in April 1892. At once the committee approached the Department of Public Parks about the statue, kicking off a cursory period of municipal assessment. Consistent with the practice at the time, no public comment was invited.

A Central Park placement was initially denied. Instead, the statue was unveiled in Bryant Park in October 1894. A “goodly number of ladies” attended the ceremony, it was reported, but in the end not a single woman served on the Sims Memorial Fund Committee, and only a tiny portion of the monument’s donations had come from the surgeon’s former patients — a tip-off, perhaps, that the hearts of women were less receptive to Sims’s legacy than they were supposed to be.

Criticism of Sims began early and never quite went away. His assistant in Alabama, Nathan Bozeman — who would himself become a gynecologist of international renown — alleged that Sims’s fistula cure had been successful only half the time. Others noted that every aspect of the cure, including both the Sims speculum and the Sims position, had been anticipated by other practitioners.

No matter. In the wake of Sims’s death and for many decades afterward, the voices questioning his legacy were drowned out by a chorus of hagiographers, whose fact-free defense of their idol amounts to a study in mass delusion. In addition to the New York monument, there were statues in South Carolina and Alabama, a Sims-branded medical school and foundation (defunct and extant, respectively), and comically laudatory profiles (“Savior of Women”) in dozens of publications. He was included on short lists of civilizational greats alongside George Washington, and likened to the divine figures in Homer and Virgil. He was dubbed the Architect of the Vagina. The apotheosis peaked in 1950 with a radio-theater adaptation of the only book-length biography of Sims, with the Oscar-winning actor Ray Milland playing the title role in Sir Galahad in Manhattan.

In recent decades, however, this began to change. A series of scholarly books — all of them brilliant but problematic — steadily chiseled away at the Sims edifice. In the late 1960s, a young scholar named G. J. Barker-Benfield produced a dissertation on how the “physiological minority” of Wasp males had come to dominate nineteenth-century America, later published as The Horrors of the Half-Known Life (1976). Smart and copious, the book included several chapters on Sims, viewing him with refreshing skepticism. “Woman’s Hospital,” Barker-Benfield wrote, “was founded very largely as a demonstration ground for Sims’s surgical skill. He needed food and fame.” Yet Barker-Benfield flubbed numerous details of the story, conflating, for example, the displaced uterus of the seamstress with the damaged vagina of the first enslaved patient. And only the profoundly Freudian predilection of so much midcentury American scholarship can explain the author’s claim that Sims harbored a “hatred for women’s sexual organs” — one that he overcame by “his use of the knife.”

Twenty years later, in From Midwives to Medicine, Deborah Kuhn McGregor recounted the history of Woman’s Hospital as an emblem of the male establishment’s hostile takeover of obstetrics, a jurisdiction traditionally overseen by women. This exhaustive volume is often on the mark: “Although J. Marion Sims is pivotal in the history of gynecology, he did not create it by himself.” But McGregor, too, commits casual errors: she mistakenly describes the VVF wound as a “tear” (a peeve of clinical specialists), and creates confusion with equivocal language and even imprecise grammar. Worse, a story that is fraught with horror and drama is reduced to stale summary by the truth-destroying academic conviction that to be dull is to be serious.

Both Barker-Benfield and McGregor failed to penetrate the membrane that separates the world of academic squabbles from that of the people who walk past the Sims statue every day. They did inspire a new generation of scholarship, but a tendency to fight fire with fire resulted in an inferno of questionable claims. Sims was soon described by one detractor as “Father Butcher,” a sadistic proto-Mengele. Even before the debate’s most indignant voices chimed in, Sims’s biography had become a kind of post-truth zone. His defenders engaged in flagrant invention, creating a saintly caricature that outstripped even Sims’s own efforts to inflate his reputation; his detractors introduced inaccuracies and exaggerations that morphed into outright falsehoods as they ricocheted from source to source.

Forty years after its dedication, the Sims statue, along with a statue of Washington Irving, was removed from Bryant Park. The year was 1932, and the nation was about to observe the bicentennial of George Washington’s birth. To commemorate the occasion, Sears, Roebuck and Company erected in the park a temporary replica of Federal Hall, from which Washington delivered his first inaugural. The statues, which were in the way of this patriotic simulacrum, were dragged away.

Robert Moses was named the commissioner of parks a short time later. He disliked statues in general, and almost immediately proposed a dramatic overhaul of Bryant Park that did not include the reinstallation of the Sims and Irving monuments. This was fortuitous, as the statues had been misplaced — five tons of granite and metal had somehow gone missing. The good luck turned into headache, however, when the Art Commission (which was later renamed the Public Design Commission, and today has final say over all public-art decisions in New York City) rejected his proposal. The statues had to come back.

Reports differ on what came next. Some say the statues turned up by accident in a Parks Department storage yard. Moses told the New York Times a different story: a protracted effort led searchers to a storage area beneath the Williamsburg Bridge, where they found the monuments wrapped in tarpaulins. Moses reiterated his belief that the “city could get along very well” without them. Still, to keep Sims from mucking up his plans, he consented to a request from the New York Academy of Medicine that the monument be installed across from its Fifth Avenue location, in a niche on the outer wall of Central Park.

Again, the public was afforded no opportunity to comment. The statue was rededicated on October 20, 1934. The speakers echoed those who had first lobbied for a Sims monument, hailing his supposed innovations without ever really addressing what such a memorial was for. In 1884, another celebrated surgeon, Samuel Gross, had argued in his letter of support for a Sims statue that monuments are not intended for the dead. Rather, they should act as a stimulus for the living to “imitate the example” of the figure memorialized. But what sort of inspiration would the Sims statue provide? After all, the man in the strange bronze overcoat was, as the Medical Record noted, distinguished mostly for his readiness to employ “the one needful thing, the knife.”

Sims would have yet another memorial before the roof fell in. In the late 1950s, the pharmaceutical giant Parke-Davis commissioned the artist Robert Thom to produce a series of forty-five oil paintings illustrating the history of medicine. One painting depicted Sims’s fistula experiments: clutching his trademark speculum, the doctor stands in his ramshackle clinic before two acolytes and the three worried slave women who would serve as his initial subjects.

Parke-Davis was sold in 1970 to another pharmaceutical giant, Warner-Lambert, which appears to have had no qualms about the painting: the company granted permission for the image to be used on the cover of McGregor’s From Midwives to Medicine. In 2000, however, Warner-Lambert was purchased by Pfizer — and Pfizer did have qualms. Harriet Washington’s Medical Apartheid, the next scholarly book to take aim at Sims, begins with an account of her attempt to secure the rights to the image. She, too, hoped to use Thom’s painting on the jacket of her book. Pfizer asked to review the manuscript before making a decision, and she refused to comply. Later, she submitted a request to use a smaller version of the image in the book’s interior and never got an answer.2

Medical Apartheid is a vast and sweeping work, which ranges from gynecology to eugenics, radiation, and bioterrorism. It is notable for having won the 2007 National Book Critics Circle award in general non-fiction, among several other honors. Yet even though only a small portion of Medical Apartheid is devoted to Sims, a number of errors crop up: for example, the author describes the bronze statue of Sims as a “marble colossus,” misstates the original location of Woman’s Hospital, claims that only one of Sims’s slave subjects was ever cured, and wrongly suggests that Sims once etherized wives to enable intercourse.

Nevertheless, Medical Apartheid finally penetrated the scholar-public divide, and efforts got under way to have the statue removed. They began with a woman, fired up by Washington, handing out flyers in East Harlem. Viola Plummer, now chief of staff to New York State Assemblyman Charles Barron, had been working with several colleagues on health care disparities, and who knows how they first came to focus on the Sims statue? It was back during the Bush Administration, Plummer recalled, when there was torture and waterboarding going on, and maybe the details of Sims’s experiments, as recounted in Medical Apartheid, resonated with all that. Or maybe it was because a statue was a tangible thing, so perhaps you could actually do something about it.

Plummer’s pamphlets caught the eye of a group called East Harlem Preservation, which put her petition online. Eventually, it attracted enough media attention that the New York City Parks Department sent someone to explain to the members of Community Board 11, also involved by that point, that the city had a policy of not removing art for content. Removing a statue, any statue, would amount to expunging history.

Albeit on a lark rather than a mission, the department had been thinking about its statuary for a while. In 1996, Commissioner Henry Stern — a colorful character who bestowed code names on Parks staffers, his own being Starquest — launched an effort to erect signs to contextualize each of the statues, busts, and monuments under Parks supervision, of which there were more than 800. A statue should be more than a grave site, Stern’s thinking went. It should tell a story.

One of the people carrying out this mission was the new art and antiquities director, Jonathan Kuhn (code name: Archive), who continues on in the same position today. In 1996, the Sims statue was for Kuhn little more than a punch line — he proudly told the New York Times that the city’s statues included a “fifteenth-century martyr, a sled dog, and two gynecologists.” The signage effort coincided with the digital revolution, so only a few summaries were ever installed in Central Park as physical signs. The Sims summary was one of the many that appeared only online.

The original version of this summary, which has since been finessed and corrected, was notable for vagueness and factual errors. First, it repeated the common but inaccurate claim that Sims innovated the use of silver wire as an antibacterial suture material. The text also asserted that the statue had been funded by donations from “thousands of Sims’s medical peers and many of his own patients,” and as late as 2016, the Parks website specified 12,000 individual donors. The actual numbers are much more modest: 789 male doctors, forty-one women, and twenty-eight medical societies. In any case, nobody at the department paid much attention to the Sims summary. It was one headache among many, and why quibble with a memorial to a man whose “groundbreaking surgical methods,” as the original summary read, “earned him worldwide notoriety”?

In 2007, at roughly the same time that Viola Plummer was handing out letters in East Harlem, Mary Bassett, then the deputy commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, also read Medical Apartheid. Bassett was uniquely positioned to appreciate what is undeniably the most scruples-testing aspect of the Sims legacy. A physician herself, she had spent nearly two decades in Zimbabwe, where the epidemiological nightmare of VVF rages on today. Largely eradicated in the West because of the prevalence of caesarean section, the condition still blankets the African continent, with estimates of as many as 100,000 new sufferers annually. There has been a recent rise in clinics dedicated to the disorder, whose victims often wind up divorced, ostracized, depressed, and suicidal. These clinics all descend from a single source: the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital, in Ethiopia, which was founded in 1974 by the Hamlins, an Australian couple, both gynecologists, who planned their facility by carefully studying Sims’s The Story of My Life.3

The advent of African fistula clinics aside, Bassett believed that Sims’s surgical subjects must have perceived his initial experiments as a form of torture. Rather than handing out flyers, Bassett invited Harriet Washington to give a talk at a health department gathering. It was Washington’s lecture on Sims and the broader history of medical experimentation that got staffers brainstorming about what could be done about the statue. They came up with the idea of a contextualizing plaque to be added to the statue itself, which would tell the story of Sims’s initial procedures.

Kuhn dismissed the idea of a plaque. Instead, he suggested, they should propose additions to the existing online summary. That’s basically what happened. In 2008, the department added nine lines to the text — which, true to form, introduced more historical errors. For one thing, the revised summary claimed that Sims had been on hand to tend to President Garfield’s gunshot wound: false. More meaningfully, the new text noted that during the period of Sims’s fistula experiments, he had “declined or could not use anesthesia.”

This skirts one of the most contentious aspects of the Sims debate. During the mid-1840s, when he experimented on the enslaved women, ether had just been introduced as a surgical anesthetic; it was not approved for safe use until 1849. As for chloroform, it would make its debut in 1847 and become widely known for killing patients in the hands of inexperienced physicians. Sims’s detractors have argued that he reserved anesthesia for his white patients. This isn’t true, and for his part, Sims claimed that the pain of fistula surgery did not merit the risk of anesthesia in any patient.4

Beyond the error-speckled lines added to the online text, nothing happened. Adrian Benepe, who succeeded Henry Stern, was more concerned with health initiatives, such as smoking in public parks. For that matter, Benepe later recalled, it wasn’t like there had ever been a grand public chorus rising up to complain about the Sims statue. And when you’re the commissioner, that’s what you do: you deal with things that take up a lot of media and public attention. The Sims controversy? It wasn’t even in the same ballpark as what PETA did to Mayor Bill de Blasio over the Central Park horses in 2014.

Since the 1990s, one of the most prominent figures in the Sims controversy has been L. Lewis Wall. Wall’s résumé makes you feel like you’ve wasted your life. He holds two doctorates, is a professor of medicine, social anthropology, and bioethics, and founded the Worldwide Fistula Fund, which has launched clinical programs to combat the scourge in Niger, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Wall has performed hundreds of fistula surgeries in Africa, and has seen firsthand the struggles of aid efforts — including local corruption and political exploitation. Just as onerous, in his view, was “fistula tourism”: non-African doctors making blitzkrieg trips to Africa to rack up “good cases.” Wall responded with two articles, “A Bill of Rights for Patients with Obstetric Fistula” and “A Code of Ethics for the Fistula Surgeon.”

The latter manifesto stands in stark contrast to Sims’s lifelong hostility toward medical ethics. He always hated rules, and a petulant inability to follow even those he had agreed to has been viewed by his champions as an element of his puckish persona. Yet Sims did sometimes pay for his rule-flouting tendencies. In 1870 — thirteen years before assisting with the Sims Memorial Fund Committee — the New York Academy of Medicine put him on trial for ethics violations. Sims had written publicly about the condition of the theater star Charlotte Cushman, whom he had once seen in private practice. In doing so, he violated his patient’s confidence and ignored an ethical prohibition against doctors seeking publicity — hardly a first for Sims, who had a ringmaster’s flair for self-promotion and had once socialized with P. T. Barnum.5 Sims was found guilty. He was given a formal reprimand, which would subsequently be characterized by his detractors as a draconian penalty and by his supporters as a slap on the wrist.

Judging from this, one might suspect that Wall would have pitched his tent in the camp of Sims’s critics. Instead, as the debate turned rabid, Wall kicked back against Sims’s detractors. No, he argued, Sims did not deliberately addict his experimental subjects to opium. As to anesthesia, Wall calmly noted, the exterior of human genitals is indeed sensitive, but that the inner lining of the vagina is not nearly as innervated as one might expect.

Wall is not above reproach. For example, he decided on the basis of the little information available that Sims’s experiments were “performed explicitly for therapeutic purposes.” This conclusion overlooks the social and economic realities of the South, and the less than altruistic reasons that a plantation owner might send a woman suffering from a fistula in search of a cure: the sexual exploitation of slaves, and the financial benefits to be reaped from breeding additional human chattel. In any event, in the zero-sum game of journalism, Wall found himself positioned as Sims’s highest-profile defender, even though he had been the first to suggest that there should be a monument to Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy.

It is worth noting that while Sims is remembered primarily for his VVF surgeries, these account for only a small fraction of his lengthy practice. Indeed, after he moved to New York City, he left the bulk of fistula procedures to Thomas Addis Emmet, who became his assistant in 1856 and further perfected the process, curing many patients that his superior regarded as lost causes. Over the next two decades, Sims would dabble with a range of horrific procedures, including clitoridectomy (performed at least once, in 1862) and so-called female castration. Indeed, Sims later became a fervent champion of “normal ovariotomy,” in which one or both healthy ovaries were removed as specious cures for dysmenorrhea, diarrhea, and epilepsy. He performed the operation a dozen times himself, killing several women and mutilating others.

Earlier in his career, however, Sims turned his attention to procreation. He hoped to make advances that would ensure the perpetuation of honorable families and powerful dynasties. His investigations into sterility would result in his prescribing intercourse at particular times of the day, and then swabbing his patients’ vaginas (to count sperm under a microscope) at such increasingly rapid postcoital intervals that critics wondered exactly what kind of bargain had been struck between husband and physician.

Sims signed on to a simple anatomical tenet of the day: if the neck of a woman’s uterus did not offer a clear pathway, then the egress of menstrual matter from the womb, and the ingress of sperm into it, could be impaired. In his view, this could lead to sterility and painful menses. His solution (and he was not the first to suggest it) was to surgically open the passage with one of a variety of multibladed dilating tools, some of which were activated with a spring mechanism once inserted into the patient’s womb: the blades popped open and made multiple incisions as the device was drawn out again.

In 1878, he published a kind of summa, “On the Surgical Treatment of Stenosis of the Cervix Uteri,” reflecting at length on a procedure that Sims estimated he had performed as many as a thousand times. Like his early publications, this one seemed designed to ensure that nobody could snatch away credit that was properly his. In this case, Sims wished to cement his claim to a particular incision made to the cervical canal. “The antero-posterior incision belongs to Sims,” he declared, “and not to Emmet, or any one else.”

The paper was presented to the American Gynecological Society that same year, and while Sims was not present, other doctors spoke up to praise or critique his claims. The most interesting response came from Fordyce Barker, President Grant’s personal physician, who had championed Sims from the moment of his arrival in New York City, launching the young doctor’s career (and canonization) with a public description of his “brilliant” fistula operation.

Twenty-five years later, Barker rose to offer a less enchanted view. He began by noting that it was unclear whether a womb with a narrow neck was even pathological. In recent years, many unnecessary operations had been performed, often with injurious results. Worse, the procedure had been adopted by untrained physicians or downright charlatans. In any event, how could it be that Sims had performed these operations five times as often as many other capable surgeons? His skills were undeniable, Barker concluded, but it was for precisely this reason that his arguments should be scrutinized, for it had been the tendency of the profession to accept the dicta of such men unquestioned.

Four years later, Barker accepted the chairmanship of the Sims Memorial Fund Committee. He died before the statue was dedicated.

In March 2014, the Sims debate reignited with another New York Times article, which described the limbo into which the controversy had fallen after 2011. Now the Parks Department and Community Board 11, which had been fighting the Sims case for seven years, agreed to meet and settle things once and for all.

The city, still resistant to removing the statue, sought out experts to make its case. They enlisted Robert Baker, a professor of philosophy at Union College and the author of Before Bioethics (2013). Baker acknowledged Sims to be precisely the kind of doctor that had necessitated the bioethics revolution: bioethics holds that science-minded physicians shouldn’t be trusted to monitor their own ethical behavior. Yet in Before Bioethics, Baker takes Sims at more than his word. For example, Baker claims that Sims freed his slaves before he moved to New York City in 1853. This is patently untrue: he leased his slaves before he left Alabama, and during his difficult first year in the city, they likely formed an important part of his income. Baker even argues that The Story of My Life should be forgiven for its use of the word “nigger” because Sims only uses it when quoting other people. Actually, that’s not true — but even if it were, who cares?

It was Baker who provided the department with a three-page “deposition” on the controversy. This document reads like a disheveled Wikipedia entry. Baker’s claim about Sims’s own slaves is there, along with an inaccurate assertion that Sims repeatedly sought consent for surgery from his enslaved patients. The document also notes that Sims offered credit to his slave subjects and that they came to serve as his assistants. These assertions are true, yet all they do is add another twist to the complicated knot of consent. Slaves cannot provide consent for surgery — they do not have true agency. Similarly, should a slave be applauded for performing labor that she is in any event compelled to perform? Regardless, Baker concluded that additional information about the three slaves on or near the Sims monument would be an appropriate way to “follow Sims’s example [and honor] the courage of these African American women.”

Parks also contacted the art historian (and former vice president of the New York City Art Commission) Michele Bogart, whose position couldn’t have been clearer: she was vehemently opposed to the removal of the Sims statue. Bogart didn’t know a lot about Sims. In her view, however, the details didn’t matter: you simply didn’t remove art for content. Bogart didn’t buy the claims that modern sensibilities had been injured. Get over it, she thought. It boiled down to expertise. What Bogart believed — and she was undeniably an expert — was that the Sims statue had stood in New York City for more than 120 years, and that even false history was of historic interest if it managed to persevere.

The meeting was held in June 2014. Baker’s deposition was read aloud to members of the Parks subcommittee, and Bogart briefly addressed the importance of using city monuments as educational tools. A deputy commissioner apologized for the years it had taken to produce a response, then reiterated that the statue would not be removed. However, the department was ready to consider a freestanding sign, and the committee voted unanimously that Parks, in a timely manner, should return when a complete plan had been formed. In other words, it was back to bureaucratic limbo, where the argument over the Sims statue — which had long since become a symbol of how the fraudulent past becomes official history — had resided for nearly a decade.

In May 1857, Sims was approached in private practice by a forty-five-year-old woman possessed of irritability of the bladder and uterine displacement. She was a curious case, married at twenty but still a virgin. Sims attempted an examination, only to find that the slightest touch to her vagina caused her to shriek, spasm, and cry. A second examination, under the influence of ether, revealed minor uterine retroversion — but her vagina was perfectly normal. Medical books threw no light on the matter. The only rational treatment, Sims concluded, would be to cut into the muscles and the nerves of the vulval opening. Alas, the woman’s “position in society” made her an unsuitable candidate for such an experimental procedure.

Fifteen months later, Sims was sent a similar case from Detroit, a young virgin with the same dread of having her vagina touched. This time, he decided, the risk was justified: her husband had threatened divorce. Cutting into the hymen offered the young woman no relief, but incisions into the mucous membrane and the sphincter muscle were slightly more effective. By that point, her mother concluded that Sims was experimenting on her daughter — which, of course, he was — and yanked her from his care.

A few weeks later, another case fell into his hands, followed by two more. By now, Sims had a name for the condition: vaginismus. He had also devised a cure, aimed primarily at permitting coitus between husband and wife: amputate the hymen in full, then make several deep, two-inch-long incisions into the vaginal tissue and the perineum. As with his cervical stenosis surgery, this would be followed by the insertion of glass or metal dilating plugs as the wounds healed. Several years later, in Clinical Notes on Uterine Surgery (1866) — sometimes characterized as modern gynecology’s inaugural text — he claimed to have encountered thirty-nine instances of vaginismus and achieved a perfect cure in every case.

Sims’s claims were challenged even before he finished making them. English doctors rejected the notion that the condition had never before been described, and London’s Medical Times and Gazette noted that British surgeons would no sooner resort to excision for a mild case of vaginismus than they would cut off a patient’s eyelid because he had a twitch. French doctors agreed. They had been researching the condition since at least 1834. They regarded the “Sims operation” as too bloody and dangerous, and one French doctor dismissed it as too mechanical, “_too American._”

American doctors eventually rejected the procedure as well, using it for only the most severe cases. They also came to dispute Sims’s claim to thirty-nine perfect cures. Years later, one Woman’s Hospital surgeon insisted that he was aware of only a single cure, and vividly recalled two patients who had been left in far worse shape after the procedure. Another doctor remembered cases in which failed Sims operations — performed by surgeons other than Sims — were followed by so many futile attempts at treatments that the women’s vaginas looked as though they had been splashed with nitric acid. A year before the Sims statue was erected, A.J.C. Skene — the other gynecologist in New York City’s statuary pantheon — claimed that he had never seen a case of vaginismus for which the Sims operation “would have been of any value.”

The debate over the Sims monument has tended to focus on his VVF experiments — but that’s only the beginning of the story. After Sims exploited a vulnerable population to achieve a minor victory that he successfully parlayed into international fame, he claimed credit for a series of bogus breakthroughs and performed thousands of surgeries, often at the behest of distressed husbands, which left many women mutilated or dead.6 This does not make Sims a Gilded Age Mengele. Mengele killed his Jewish subjects by degrees, extracting data along the way, while Sims was always attempting to ameliorate something. Good intentions, however, don’t erase the enormous pain and injury that he inflicted, nor the sense of violation — one felt by women today every time they pass the statue on the sidewalk.7

The anti-Sims movement has never had the fervor of a student uprising. And for more than a decade, it lacked even the figurehead of a vigilante arrested for defacing the statue in a pique of righteous inspiration. That shouldn’t matter. Not all scholars of public art agree that statues should remain in place forever. Experts of a different kidney, such as Erika Doss, a professor of American studies at the University of Notre Dame, are perfectly comfortable with monuments being “defaced, despoiled, removed, resisted, dismantled, destroyed and/or forgotten” when they represent “beliefs no longer considered viable.” These acts of symbolic vandalism embody Emerson’s insistence that good men must not obey laws too well.

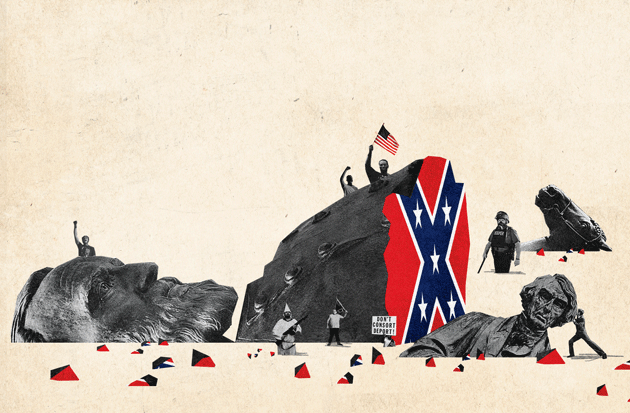

Like history itself, activism seems to move very slowly at times, then abruptly accelerates. In June 2016, the long-awaited language for what had evolved into a freestanding-sign-plus-plaque solution was presented to Community Board 11. The expectation was that the board would provide yet another rubber stamp for yet another round of evasive action. Instead, a subcommittee balked — and after another presentation, two weeks later, the full board voted to remove the statue. Then the Confederate flag came down over the South Carolina statehouse, and Confederate statues vanished in New Orleans, Baltimore, Orlando, St. Louis — and in the wake of Charlottesville came a growing sense that the nation could no longer tolerate commemorations of its most shameful moments. And finally, on August 19, protesters congregated around the Sims statue and demanded that the city remove it.

In the media storm that followed, Mayor de Blasio instituted a ninety-day period of reevaluation for the city’s sprawling statuary. After years of telling activists that there was no way to remove statues, the city invented one. Still, it wasn’t enough for one protester, who at last seized the initiative and spray-painted racist across the statue’s back and gave it red, villainous eyes.

Surely this Emersonian good man — if it was a man — had been prodded into action by the activists, one of whom condemned “imperialist slaveholders, murderers, and torturers like J. Marion Sims.” But truth be told, that’s not quite right, either. For all his crimes, Sims was not a torturer or a murderer. Which means that his detractors are on the right side of history, but for the wrong, or incomplete, reasons. And maybe that doesn’t matter. For ten years, the Parks Department and the city itself resisted removing the statue not because they cared about Sims but because they feared a precedent that would bring a cascade of other statues down as well. That’s exactly what should happen, in New York and elsewhere. In an age defined by changing values and an evolving notion of what constitutes a fact, the Sims statue stands as a monument to truth’s susceptibility to lies and political indifference. Removing it represents an awareness that history is fluid, but bronze is not.