Trapdoor, by Kathleen Alcott (original) (raw)

Toward the end of my life in New York, a decade and change I would dispense with as casually as I’d begun it, came a season of psychic misery that felt as vertiginous, as alarming and noiseless, as a winding drive along a cliff—the windows sealed shut against a danger still visible. My acupuncturist, Christina,1 might have been the only person who knew how truly I had wanted to stop living. Six months into treating me, a period in which my thanatotic impulses could alight on certain objects as glistering and totemic, she moved offices, taking up in an unremarkable office building on Union Square. It was December of 2021 when I first visited her there, on a half-vacant ninth floor, and an elevator opened to reveal the most unusual door I had ever seen. Isolated at one end of the hall, it left me succored, almost beatific. On glass painted black, unsteadily at the edges, was a prim gold-leaf heading: office of the estate of samuel klein, deceased. Under that, six names were printed in the same serif—the text dec’d appended, with a baffling kind of menace, to three_._ I felt convinced that the knob had not been turned in recent history: whoever was responsible had declared themselves bereaved, a few times over, then vanished.

I’ve always been bored by the prospect of ghosts—I spend my fear on what life may contain, not what death might imperfectly silence—but I do like to feel in conversation with the decades that made my life possible. At the outset I believed this explained my feeling for the door. I imagined what decay and pestilence lay behind it—Dictaphones and hatboxes, green Tiffany desk lamps, ossifying mimeographs—but I was more fascinated by what it was than by what it might conceal, its silence nonpareil in a New York that had become, in the pandemic, operatic with a very American chaos. Its hush seemed to repudiate the shrieking city beyond, but it also forgave my darker contortions, my thoughts of vanishing that had not seemed fit for the lissome fountains or eager traffic, the pregnant clouds discoursing with great buildings outside.

I would die, I later texted someone, joking and certainly not, with a photo of the door, to work in peace. It was true that I’d been having a difficult time working, a problem that was more troubling for the fact that working—writing—was all I’d ever been capable of doing. The peculiar velocity of the fiction writer is to race head-to-head with what you’ve repressed until it overtakes you—whether to leave you tailing in interest, or overturned on the pavement of your real life, bloodied where the truth has cut you off. I was too young when I sold my first novel, twenty-two, to consider what it would mean to keep this kind of big-data cloud on my subconscious. Three books and a careerist, monomaniacal decade later, that record became the officious appendix to the jagged, episodic, spiritual crisis into which I fell.

When I had first gone to see Chris, it was ostensibly for a physical ailment, a startling pain at the base of my neck that physicians and chiropractors had not helped. It had come on with no inciting event, keeping me from turning a lock without a bolt of agony. I was single, thirty-two, living alone in pre-vaccine isolation, and I shattered three glasses in a week trying to lift them, and the injury felt tantamount to a judgment—if I had made different choices, if I’d had different priorities, then I would not have been trapped there, in the dark that was coming early and total, sliding toward me like water: someone loving would have risen to turn on a light. I had always felt my work was more important than I was—who cared whom I hurt, where I lived, or for how long—and I had mostly avoided the slow grade of real partnership, anyone who might reliably appear with a bag of vegetables or expect me to do the same, opting instead for obvious shows of smoke: relationships that took place suddenly in other countries or pressurized seasons, with remote people who flickered into oceans to surf or mountains to climb or wars to report, sending exquisite letters and allowing me, in their distance, mine. What I needed from any relationship, I would say, haughtily, was privacy: to be able to shut the door.

Until the inexplicable injury, I had been a zealous exerciser, demonstrably or hideously vain—too thin, the content and zaftig and married people in my life felt comfortable announcing. I had taken great care of my body, running bridges in balaclavas when winter slipped ruthless, because my mind was somewhere I didn’t want to be left idle. I speculated that the pain might have something to do with the unusual position in which I slept, on which most people I’d been with had commented. Mangled, one man I loved said, seeming relieved I was finally awake. The reasons for my tendencies, waking and sleeping, had been hidden in my books and stories all along, but I had refused the pattern, and then my body had revolted.

When I mentioned the macabre, bituminous door to Chris, whose demeanor is something like a time-lapse of spring—brutality and kindness cycling in rapturous color—she did not have much to say. She had ministered to me while I lay in so many different kinds of crises, her face said; she had tried to help me in so many ways. Cupping and moxibustion; lancing and needling; something experimental called battlefield acupuncture, which involved her piercing my auricular cartilage with needles that stayed there for a week. Had I forgotten the months I felt hunted—by thoughts of death and risk, illness and drowning, accident and suicide, and by a particular secret of my childhood, which I had confessed to her as though I had just learned it? Chris, whose belief in qi had so often embarrassed me—there! she would shout, hearing what she claimed was my blood finding motive force—wanted me moving in the direction of life.

It was as if she understood that the door would magnetize that dark dimension of my thinking, the death drive that had made me alternately brave (or pathologically reckless) and clinically sad, and which I had always explained, perhaps a little too easily, with a constituent history: when I was young, before my brain had quite finished forming, my family died. I had struggled with how prominently, on the hierarchy of personal identifiers, this fact was meant to sit, even as I bitterly understood, and wished others would understand, its separative effect. The door, in its static defeat, was a palliative: proclaiming a past that would always be happening to those who had experienced it, as well as the sovereign right never to discuss it.

Walking Home with Flowers, by Claudia Keep © The artist. Courtesy MARCH, New York City

Writing fiction is a recursive disavowal, a psychic chase that requires moving between what is known about the self and where you vanish when you refuse to know it. It didn’t occur to me until recently that I learned to dissociate early. As a reedy adolescent, spotlit onstage in adult repertory theater, I was already fleeing—reality in general, or the sound of my father’s portable oxygen tank, which followed him around like a pet. It didn’t occur to me until I heard one again, by chance, in public, and immediately moved to find an exit, how its once-a-minute hiss was the rhythm and ghoul of my childhood, or how a minute, to a child, is just long enough to disappear into it—lie to herself that something menacing isn’t coming, feel frightened anew when it does. If the sound of my father reached me at all from where he was a faithful member of the darkened audience, I would look deeper into the lie of the play, spreading my shoulders in the clothes that weren’t mine, enjoying conversations that always swung along the same hinge in another fixed time.

My first mingy paycheck as an artist came that way, a four-hundred-dollar stipend the year I was thirteen, a season in which I was the only child at rehearsals, and enraptured by the prospect of psychologies that weren’t mine. All spring the sweatered director preached the Meisner technique—the same line, spoken a hundred times—and I watched divorcing, middle-aged actors, sitting in folding chairs under stage lights, come to weeping by how the same words could transfigure, or blacken, if you repeated them continuously, if they were the only words you had. I remember the relief of reading about myself in a newspaper for the first time, a review of my performance that made me feel realer than I ever had (I was not anyone’s daughter, I was not my life but a fact in print), and then the anxiety when I understood it might be some time before I was real again.

Maybe the Meisner method’s tacky circularity intrigued me because it told me there was more I could learn, on my own, about things I could not really speak about. I was already turning over the same peculiarities of my childhood, the years my father had worked out an arrangement, after a period of living in his car, in which he would squat in a desiccated barn in the backyard of some neighbors of my mother’s. My parents had met at the Oakland Tribune in 1987—he forty-six to her thirty-four—but by the time she was pregnant were both mysteriously unemployed and uninsured, perhaps due to involvement with substances that made life easier. They married, packed up for a folksy town of forty thousand people one hour north, and two years later were divorced. There was only one house between ours and the lot with the barn: that of Martha and Peter, a one-dimensional pinnacle of happy whiteness—a dalmatian named Pepper, a baby on the way. I would sometimes hitch myself up the meager fence that bordered my mother’s rental to peer over their groomed backyard, spying in order to catch a glimpse of my father’s aggressive misery. He could usually be seen, through a gap that had once held a hay door, on the upper level, and it shamed me that he had no privacy. Their emerald lawn, his orange piss pot; their shining deck, his dewy sleeping bag; their white gazebo, his brown liquor.

There’s no one left to ask why this seemed like a fine idea, allowing that laughably horrific aperture onto his dysfunction. My mother, in those years, was on public assistance and nursing to death her brother, who was in his mid-thirties and vanishing of AIDS—an extravagantly beautiful chef who insisted on cooking what he could no longer eat. She’d moved him into her bedroom and herself into mine, onto a mattress where it calmed me, from the vantage of my loft bed, to watch her sleep. I seem to remember my father’s argument was for proximity, and that I was meant to understand his homelessness as a sacrifice undertaken on my behalf—his talents were too big for that small town, and if it weren’t for me, he would have been elsewhere. Once a leftist of some volition and a journalist of some promise, though not the fame or importance he insinuated and taught me to insinuate, he spent the last five years of his life an imperious gas station cashier, friendless and malignant, picking shouting matches with customers he believed had condescended to him. When this happened in my vicinity, I would pass out back to the station’s garage, studying oil spills in the concrete as though they were clouds in the sky. I stopped acting when he finally died, the year I was fifteen, maybe because I no longer had the practical need. The years in between his dying and my beginning to publish—fifteen to twenty-two—are more or less lost to me. I was a bright girl in handcuffs, in and out of school, drinking opium in a narrow lace dress, falling from one level of a staggered roof to another in the middle of some brownout, barbacking for a season in Arkansas, dreamily pregnant in an alpine river and putting off the abortion, asking for trouble, trouble itself.

My cosplay of the past started at twenty in San Francisco, where all of my friends and lovers were in or orbiting bands like Thee Oh Sees or Ty Segall or Girls, Sic Alps or Royal Baths, who had digested polyphonic Sixties psychedelia or melodic Seventies hedonism to critical darling reception. California is a great preservationist of these decades, in part because the weather is less destructive to old things, and in part because its children, raised on the records and films that go on describing the twentieth century, harbor a magical belief that they invented it. We took all the same drugs, among the same trees, in the same clothes, that the culture we worshipped had directed us toward. We had Chelsea boots or winklepickers that clasped to one side, minidresses with accordion sleeves, shrug coats in jacquard chenille, and we smoked on marble stoops with a vague but animating revanchism that was not, in the peculiar blush of the first Obama Administration, altogether political—mostly a cruel scorn that might be directed at anyone who did not belong. This was the eve of the Google Bus, Google Glass, the bros in high-tech performance fabrics, but recession-desperate landlords were already throwing startups cheap leases in art deco buildings downtown. The end of our lotus-eating era would be particularly devastating to those who stayed to resist it, and the cautionary tales, later, were the people we had all known, who in the space of a decade went from appearing in the pages of fashion magazines or Rolling Stone to sleeping in ATM vestibules, moving in with their mothers, or busking on Haight. I would remember one of them, how back then he’d seemed gentle to all the world, as tender with the crabs at a tidal pool where we might drive at dusk as he was with the cocaine on a gilt mirror, forever parting his long honey hair to one side or another, arranging fresh ranunculi on his mantle. I spent a week or three sleeping in that bedroom, under those cherub cornices. Though I can recall with him, with many of these people, that beneath the pretty images they projected it was hard to locate the there there, it didn’t occur to me there was a reason I liked to be around that, or that I couldn’t find their suffering because I didn’t want to look for it. It didn’t occur to me I was becoming a paper lantern myself.

As a writer among the musicians I was something of an interloper, watching for some egress I would know when it came, and I got out before the city emptied of culture in earnest. My real life began, or that was the way I put it to myself later, when I published a lugubrious piece of hagiography about my father, repurposing his own vainglorious phrases. [My father] was almost killed once looking down the barrel of a machine gun in occupied Czechoslovakia while working for Radio Free Europe, once by an erupting volcano he stood on the rim of in Hawaii for the sake of reporting on it. The piece enumerated his achievements, tidily summing up the sorry end of his life as some honorable consequence of the spectacle of Cold War decades in which he’d been so heroic. It gained me an agent, and I moved to New York, where she sold my first novel, and I started to associate with a different kind of person, Waspy, educated, rule-following. Very few people dressed the way I did, and no one knew about the ways I’d behaved, and then I stopped thinking of my father.

(My mother’s life ended much more suddenly and politely than my father’s had, soon after I left California. In March, she turned yellow as the daffodils just risen. In April, it seemed like all in one Sunday, she received the terminal pancreatic cancer diagnosis, decided she had better file a tax extension in case, showed me a meteor shower she had hallucinated, asked to use the bathroom, and died.)

Though I had long since drifted off the stage, my habits as a New Yorker must have appeared to others as eccentric or narcissistic theater. I had stepped, wittingly and not, into a new image: a distraction in pale green sequins, passing out of the revolving doors of midtown buildings with the last dinosaurs of publishing, old white men who taught me how to order a martini and from whose fiction mine seemed descended as they touched my knees. I did or could not think much about why my life had to look the way it did, whether snobbery was a response to trauma, appearance a layering response to unwelcome depths. I had stalked thrift stores and flea markets, becoming a manipulative, garrulous haggler. I had taught myself what World War II had done to womenswear, what certain epidemics had done to ideas about décor and furniture. At various points, I owned a celadon silk ball gown from the Twenties, a framed original advertisement of Kenneth Noland’s first show in a New York gallery, a Swiss art nouveau catalogue of mountain flowers, a coffee table book that bragged about the 1966 destructive flood of Florence, an original double-breasted Rudi Gernreich bikini in impractical blue wool, a seventy-pound brutalist copper headboard marbled tawny and psychedelic, and a russet 1975 Volvo 164E. The car had no airbags, and, for the first year I owned it, a faulty brake booster, and it inspired at least a few dreams of my dying in flames.

What I loved about New York was not just how many eras went on simultaneously—the Eighties in the chunky Memphis Group shapes for sale in the bleary lighting district along the Bowery, the Sixties on uptown corners where you might see hats like wedding cakes disappearing into a yellow taxi. It was a breeding ground for a kind of temporal irredentism, creating small countries of people who had not kept up, and could survive by finding others among the eight million who had also, however obliviously or resolutely, refused the zeitgeist. My cultural intake had always been skewed toward music and paintings and films already canonized, and maybe I was happiest in the warstruck chiaroscuro of Marcel Carné, or the tilted feelings of the fauves for the woods, because I had read the theory, understood the trajectory of the movements. I knew which questions these pieces would ask of me, and if my horizons were low, spangled with spontaneous, sense-driven interactions and transactions, they offered me a kind of control I could never enjoy in my life with people. I gave little thought to the remark those behaviors out in the world made about my life in my mind—that perhaps, in order to avoid thinking of my past, what I had cultivated was a very obvious presence.

I hadn’t known I was intent on transforming upward, but I remember reading pieces in the New York Observer and the Daily Telegraph, out of London, that described my appearance when there was no need to describe my appearance—“more Madison Avenue than Bedford Avenue with her bright blond hair, pocketbook and well-cut pastel outfit . . . too put-together to be at a party with $3 drink specials,” “she dresses like a cross between a 1930s lady librarian and Diane Keaton in Annie Hall, all raffia clutch bag, sensible heels and mustard and beige tones”—and understanding I had pulled off a trick without really meaning to, that the feminine silhouettes that had yawned with some ironic bite in drug-smeared parties in the Mission and the Tenderloin scanned very differently elsewhere.

As the decade floated down, I populated my life with lucky, wealthy people, whose troubles I privately, selfishly, never saw as quite real, and whom I always started to resent after enough time had unwound. Why was I angry with them for seeing me as one of them, I wondered later, when for years I had contorted myself in order to pass, donning the correct wool blazer, living in the $3 million brownstone of a much older boyfriend, teaching at the right universities, learning to eat from atop the convexity of my downturned fork tines, excusing myself to the restroom if the topic of my early life went afield of the slogans I’d devised, doing whatever I could to belong there and then, and not to the places and times I had left.

New York was the most hospitable environment for the way I needed to live, the paintings and buildings and cinemas and gardens a companionate supervening of relationships where I never really told the truth. I paid for cold borscht in private, traceless cash at B&H Dairy on Second Avenue; developed a psychosexual, contentious codependency with a gifted Russian cobbler named Gregor; bought braids of sweetgrass at the one Indian health food store that carried it; regularly spent twenty minutes in line at Film Forum, making conversation; met a stranger on a C train stalled for half an hour and spent a summer in bed with him; went without notice, as was later largely impossible, into museums and galleries. But still I couldn’t manage the city without taking seasons, sometimes contiguous, away, meaning that people started asking where are you instead of how, which I must, in retrospect, have preferred. I loved my clothes packed into grids of color, the wheels of my suitcases slowly grinding into teeth. As my twenties dwindled, I shuttered my social-media accounts one by one, relishing the vanishing silence, the insistence that real life was sensory. My tastes were a locating religion, and my absences made it easier to icily break with many of the people of rarefied privilege with whom I’d become closest, and I observed my life with quiet righteousness as I whittled it down, as if I were not the one who would have to survive it.

Pessoa writes, in The Book of Disquiet, about an aesthetic being the saving grace of a secular life, describing a necessity in the vacuum left by the church who had architected one’s very subconscious. One has to live her waking hours understanding their influence on dreams, the book entreats, to prize the dreams above all else. This is, in fact, no way to live, though it is a way to sleep.

It’s hard to remember exactly what I said to Chris, sobbing on her table in the winter of 2021, and easier to picture how she touched my face when that was a public health risk, and spoke my name while drawing breath from the same air. “It’s going to get better,” she had said, covering my bare body in medical paper, placing needles between my eyes, along my tibia and scapula, between my metatarsals. I was stunned to have found her, Christina, whose intake was two hours, who spoke to my insurance company to get me further care, who took notes with the dedicated focus of a professional interpreter.

But I guess that came later, her assertion that I would want to live my life rather than end it, as my mind had begun to obsessively threaten, once she had begun to treat me in earnest. I must still want to skip over the conversations we had at the outset, which I still cringe to recall, talking about the way I slept—on my stomach, left knee craned up, face screwed way right, arms cactussed in opposition.

Why did I sleep that way?

I wasn’t sure, I answered, perhaps angrily, bothered by her bluntness. I had for as long as I could remember. But that was nothing I could help, and I had come so she would help me.

Why did I sleep that way?

I guess, I hemmed, because I’d had to share a bed with my father, when he’d had a bed, until I was about twelve, and because I’d kept my head away as so not to see him. Because I’d despised it.

Why did I despise it?

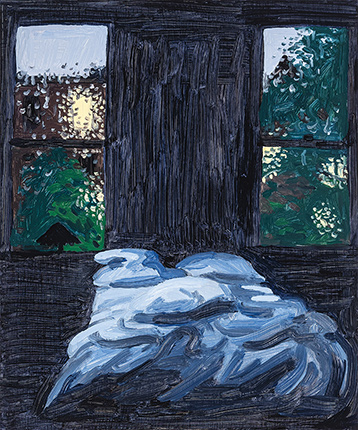

Rainy Night, June 1st, 8:43 pm, by Claudia Keep © The artist. Courtesy MARCH, New York City

The answer was not, exactly, that my father had raped me, although the effects—namely, that he had made me feel soiled for eternity, separate from other people and so intent on avoiding commitments to them—were similar. My issues with intimacy were written not just all over me, but by me, in the fiction that knew me better. That’s what passed for paternity, I had written in a short story, in the voice of a woman describing her father. Making your daughter your little wife. In every novel I’d written there was some kind of sexual disassociation or abuse, some kind of trauma experienced by a child who later fails to enter their own maturity, their own consequences, so exposed have they been to the intimacies and failures of the adults around them. There are some writers who keep copies of their own books on display, but I had always kept mine in boxes, hidden in closets and storage units and under where I slept.

And though I had always had trouble sleeping, I hadn’t ever had trouble getting out of bed until, in the silence of the pandemic and the cage of my injury, I remembered what I must never have really forgotten about my father. It was not just how he threw glasses and screamed, or would floor the gas as a way of inciting fear until I spoke the apology he demanded, but how there’d been a sexual and romantic skein over almost everything he said and did. Rather than pay child support, he would send me what could only be called love letters, particularly after some episode of violence; rather than drive me to school, he would manically spend his little money on what could only be categorized as extravagant dates. Trips up in a single-prop plane, out on the bay to whale watch among the Farallon Islands, into some tacky open-air market to get a henna tattoo on my exposed shoulders, all the while taking photos, a roll of film in an afternoon, for all of my childhood asking that I pose against hill or ocean, edging closer on his knees to get the right angle. He would speak to me about the women he was sleeping with, and, by the time I was about ten, after he was firmly isolated by his illness or his dysfunction, graphically about the bodies of those he would like to, how long it had been since he’d been touched, what that did to a person psychologically, there were studies, there were essays, I should read them, he had left me something to read. My appearance was often the subject of letters he mailed to me at my mother’s, a fixation that drove all the thin-strapped dresses he bought me when he had no place to live, then the portraits he paid photographers to take.

I had been in therapy on and off for ten years, mostly, I thought, to deal with being orphaned by early adulthood—but somehow I’d avoided the topic of my father’s behavior, perhaps because of how much I’d needed the story of his life, as he’d related it to me, as a cornerstone of my own myth, and in part because I felt my traumas would have been illegible. When I went to see Chris, she had done me the intuitive favor of treating the maladies coming off my childhood as though I remained the child experiencing them, asking questions so facile, so sincere, I could not condescend to them. Do you know there’s no way he’s coming to get you? she had asked, and I buckled and I wept, scorning the sincerity of the exercise at the same time it unzipped me. There was nothing as humiliating or as painful as being an adult confined to childhood, I thought, then how that enclosure was just the other side of the trapdoor you fell through after being a child confined to adulthood. I could locate no memories of my father assaulting me, only a childhood and adolescence enduring physical transgressions just at the threshold—his fingers in my mouth some sixish years later than I was teething, shirtless massages I could only manage with my eyes boiled shut, mysterious detours to other people’s guest rooms for solemn conversation—expecting, subconsciously or not, that someday he would.2 It explained an anxiety that had always followed me, the hollow curiosity about suicide that my mind would surface as a narcotic, and the distinct, irrational suspicion I’d always tendered: I would die young. When I looked into the consequences of being sexually abused as a child, this was buried among them: the sense of a foreshortened future. Coupled with that sense was this fact: victims were much more likely to suffer a premature death.

My clearest memory of that season of recognition is calling an ex who’d been hideously abused in his own childhood. It had been years since we were together, but we still addressed each other as baby, and I was walking through Central Park in a white wool trench coat wondering why that was, thinking we were perhaps both the kind of people who needed that infantilizing illusion—someday, our sleep would be protected by somebody else. Maybe I had called him hoping to be told how different my experience had been, but as I qualified the ways perhaps my father’s behavior didn’t constitute abuse, he giggled wickedly, lovingly, the way you might at a child’s insistence of some unreality. Soon, I might as well have told him, I will open the first vegetarian restaurant on the moon. Why vegetarian, you must ask the child, before you tell her: honey, it’s never going to happen on the moon.

What I had experienced, a new therapist told me soon after, with no equivocation or doubt, was called covert incest, and I went mute and wondered if I was going to black out. I had conceived of the chaotic years after my father died as grief, but half my life later it was clear: that was time lived not with the negative outline of someone whose care I’d lost, but in the ragged shape of a weapon that someone damaged, or evil, had cut me. I had made the lie about who he was so foundational that the truth was like some illimitable gossip, reaching back into everything I’d achieved or owned or planned—the five hundred thousand words I had published, the brown tweed suit with mother-of-pearl buttons, the people I had cared for and the reasons I had cared for them, the vacations I had taken in ancient cities, or dense South American rainforest, where I thought I had been happy. It made the rest of my life seem like a deception, too, and then, for the first time I could recall, I could not recall my reasons for getting out of bed.

I asked Chris to take a photo of me on her table that spring, during a session when I was so obscured by paper and needles that there was almost nothing to identify me except the horrific bevels of my hip bones, and when she sent it to me later I could see what people had been saying about my body, the concerning and total lack of adipose tissue. But I also felt relief in what the image would have suggested to anyone: I had been the subject of some experiment, and I had finally, mercifully, perhaps honorably, died.

I scuttled like a roach beneath the surface of a year and a half, on Zoloft and Ambien, Lexapro and Adderall, Wellbutrin and Clonazepam and Gabapentin, temporizing, knowing dimly that Christina was correct about some change I needed to make to my life. I remember not that much—sobbing phone calls I took in the snowy park. The paper bags from the pharmacy that cluttered the bottoms of my purses, the wheezing, vanishing, blue-gray people who sat in the peeling vinyl chairs by the pickup window, resigned to whichever delay of the pill that wouldn’t help them much. A month I was pulled between someone male and cis-het and someone trans and non-binary, both of whom, in the rapidly unfurled and accepted umbrella of vanilla S and M that had entered even the lexicon of advertising—you could see buses advertising products for “every single submissive”—wanted to be called sir. It was sort of funny, an old friend and I laughed, how making love had become the subversive sexual act, though when I thought about this alone it wasn’t funny at all. During this period I flickered in and out of aesthetic anonymity, cutting off the waving hair that had kissed my waist, wearing fishermen’s wool and rubber boots, wondering blankly, newly, if I was meant to be a woman, if I was meant to be a writer, what, most plainly, I was for. Judith Butler describes gender as an imitation without an original, and while it is true that I had always imagined my femininity first as how it would be photographed, I had not realized that the imitation I had come to perfect was of a woman who would have been company to my father in his glorious past—passenger, perhaps, in the car crash in a Spanish olive grove. He bragged that he survived it, under Franco’s regime, with Afghan heroin in his pocket.

When I came to, vaguely stabilized, when I watched someone careen down the sidewalk on one of the electric scooters that were suddenly ubiquitous, when I noticed their full-face monoglass that was protection against both COVID-19 and the sun, it was the spring of 2022, and I could no longer really locate the past I’d haunted. I’d spend an afternoon at the gym and thirty minutes after in the sauna, suppurating with impressions of the altered world outside, how on most blocks you saw the newly installed freestanding public touchscreens—which looked and functioned like a phone but at a 1,000 percent scale, suggesting that if their own devices died, people would only accept help from something that looked like a bigger, permanent phone. The height of the pandemic had diseased the internet with a warty banality of white centrist think pieces about virtual office culture and virtual friendship culture and “the new normal,” but I read nothing about how it actually felt to drag a physical self through a city that seemed insistent upon its new irrelevance. Even in the sauna, which I needed to be a final bodily refuge, people were on TikTok, texting and vaping, were wearing their gym clothes and putting their sneakers up on the wood and sniping at each other, as I seemed to hear all the time—the period of nearly socialist solidarity, the messaging on the subway directing us to protect one another, had fallen. Everyone understood, Americanly, that no one was coming to save them: it was every man for himself.

I claimed that the way New York made me feel now had to do with this era of selfishness and neoliberal technologies, with the blue light that seemed more preponderant than sun—I asked friends whether it did not seem like two years had elapsed but twenty—but I also knew that the way the city had seemed to transform was painful because of how obviously it insisted that the years of my blithe denial were over. After the city’s reopening, I could operate again in some of the ways I preferred, but I couldn’t even squint and fool myself that around the corner was some restaurant where I’d repeat the lines about my early life, about my father, and be believed, because I no longer believed them myself. My father, I used to say in interviews, made me into a writer, insisting I memorize words out of the dictionary. It was my greatest casuist pirouette—taking the fact that he had put words in my mouth, imbuing it with a flourish of moral worthiness.

Swimming in Dark Water, by Claudia Keep © The artist. Courtesy MARCH, New York City

In the summer I left the city to travel for a few months, sensing I would leave it permanently after returning in October. Christina was characteristically forceful; tucked in her blunt approval of my leaving was her criticism of the fact that I had stayed. On my way out of her office, I passed the door I had first seen the year before, the list of its dead. I hadn’t told Christina that the door had become the last point of interest in a city that I had long stopped feeling curiosity for, and which, I selfishly and insanely felt, had long stopped feeling curiosity for me. I never mentioned how, during on and off bouts of insomnia, I’d gotten out of bed and googled the door with the thin, rote hope of someone putting on a kettle. During the sifting, spiking silences of two and three in the morning, I’d learned that the fourth person named on the door had also died; that the Klein family business, a discount clothing store, had in the Thirties been the largest womenswear store in the world. I had felt a real longing, imagining the riches to be had for a steal—Klein, an erstwhile tailor with famous taste, claimed never to stock fewer than two hundred thousand pieces, and the prices hovered so low that the racks were befouled by riots. To those who had an eye, S. Klein’s became an apparatus of upward mobility, but then the wealthy started shopping there for sport. It was the same story of class ascension I understood, building a life of costume and stage sets, the same threat that someone of means might slip around the back of the façade and knock at its flimsy supports.

The door seemed to suggest the present had never outpaced the past, as mine had not, that then and now lived alongside each other in a gentle custody agreement. Chris would have shaken her head if I mentioned this, turned her back to wash her hands. Perhaps, in the silence of her dismissal, I might have considered why this dissonant comity granted me such relief—how it demonstrated that life could contain two versions, and they need not contradict, speak to, or comment on each other.

At the base of the Pyrenees, in an economically bereft Catalonian village of a hundred people, I spent the afternoons after I’d written hiking into dry mountains, swimming in deep gorges, filching hot, wild peaches from the gnarled vestiges of an orchard abandoned some decades before. This had been a habit a long time, leaving the city for more and more remote solitude, and I had always needed to face trouble this way—alone above the tree line, down among a littoral cave system, when it could easily be said that no one knew exactly where I was, or gliding through a river or sea at night, where I could see my body as the same color as everything that surrounded it. Just as my fiction had hidden the more painful truths about my unhappiness, it had suggested a certain answer to it—the characters in it often disappeared to land, were last seen with a newly high, newly distant third-person narration, desperate then peaceful, passing into desert, vanishing into water or trees. Is this safe? friends had asked, over the years, the kind of familied people who cling to rocks and peer at distances. A death wish always has a brighter part to it, and this was mine, that I would climb high and swim deep, go alone and go far.

Toward the end of September, late at night in Madrid, hearing the susurrus of the very drunk meandering under the balcony, I witnessed myself email about a rental in northern California. The house sat on a hill in an unincorporated community of one thousand on the borders of Hitchcock country, far removed from any major freeways, where the pale belfries and golden hills are largely preserved by the burden of getting to them. I assumed it was an emotional coin toss I’d volley before myself, that I’d never live anywhere close to where I’d come from, that I’d back out once the possibility was real. I’d always looked down upon those who lived within driving distance of their nativities, believing that the point of life was lapidary, not continuous. But soon after I was taking a video tour, sending money across time zones, and then I was in New York packing up a decade of my life. Twice I called the number listed for the Klein estate, which never rang and went straight to voicemail. Wanting and not wanting a voice to answer, I was filled with the kind of shimmering dread that comes for the hallucinating, whose frangible place between worlds is the more frightening thing than the delusion itself.

Once the floors of my apartment were swept and all my possessions had been loaded onto a truck, I made a plan to say goodbye to Christina. When the time came and the elevator doors opened, I saw that the door was gone. It had been replaced with another—galvanized steel, the fodder of heist canon, absent of text or any other human indication. Pulling up a photo of the door on my phone, touching the steel, touching the other doors, zooming in on the photo to be sure I had the office number right, I was convinced the image was correct and the world was not, and I paced the hall, believing, as I tend to when confronted with some unquestionable fact, as I had for seventeen years, that I was not the one mistaken.

Standing outside Christina’s office, we hugged a long time, and when I brought up the door’s disappearance, she answered that the executors had moved offices, from the ninth to the third floor. When I passed down to see it—the 900 that no longer made sense, with direct neighbors on its left and right, much more visible than where it had been for eight decades—I found details I had missed when mistaking it for a monument. Around the gold-leaf letters, outlined with a fine brush in black paint much glossier than the matte that surrounded it, were the imprecise stitches of what appeared to be permanent marker: someone, trying to emphasize the names of the dead, in the places where the original outline had faded, had left tiny claw marks of another black, and the chamfered wood framing the glass seemed recently repainted gold.

Staring at that glass which reflected nothing, my last night in the city, the last weeks before the clocks would abbreviate life into winter, I was galled by my long misconception—that the executors had baldly enunciated their grievances, then kept as far from their past as I had from mine. Instead, it turned out they’d always kept vigil, making small annotations to the boundary between life and their losses, to memory as they stood before it, leaving flowers, however stray and ragged.

In my last moments by the door, I scrawled a note to the two remaining executors, both likely in their eighties or nineties, slipping it through the mail slot’s brass tongue, telling them I was fascinated, asking whether they’d speak to me. And just as they would not to the message I finally left on their answering machine, no one ever responded. I admired their evasion, for the right they were exercising was not so different than that of which I had availed myself. To live in furtive independence, however isolating or unpopular—to accept few messages, despite having left some, blatant, alarming, for others to read.

I arrived in California after dark, taking serpentine roads through fog, relieved to discover how frequently I had no service. Signs were everywhere, indicating distance and direction, insisting that the body went on without a digital shadow, unsynced and unreachable. I sat much of the week on my forested deck, surrounded by old-growth redwoods and lacy buckeyes and winding, mossy oaks and spritely palms, everywhere I looked another kind of green—sylvan, olive, that bluish juniper, an emerald glossed almost to black. Maybe I had come to witness some ending, the state as it buckled and myself as I molted, to pay penance for all the years I had not come home. I might last six months, I might make it a year, but now it was fire season, and it was easy to picture, foolish not to imagine, what those trees would look like gone orange and red: how I’d run out through the smoke, taking close to blind those same roads I had taken in, hurtling unknowing past gulches dry so long new life had begun to grow on their floors.

A few days in I hiked to the highest place I could find, winding toward the smell of ocean, coming across crowds of quail who moved like beads of the same necklace, elk that looked like shadows printed on the loamy distance. Rising six hundred feet, through verdant copses and others where burned trees looked like knives, I finally sat to cry. I bawled because I had escaped or finally knew I never would entirely, not my hometown or my class or my adopted city, but an idea that had stalked me since I was born my father’s daughter: that my life was not really mine, but something he’d authored, and which belonged to him. So much of my life as a woman had been an assertion of my elemental separateness, living and dressing so I would not be mistaken for anybody, itself an orchestration of my wish never to be mistaken for anybody else’s.

I thought then of the first time he got me high, when I must have been eleven, coughing hot smoke. We were lying on top of the covers in his rented room, amid the meager possessions of his life—a carved wooden box full of foreign coins and gold cufflinks, the curling photo of Gandhi and printed Pete Seeger lyrics he had pinned up above his typewriter—and he asked in the pleasant, curious tone of a philosopher whether, if he could find a scientist who would halt my aging so I’d remain his little daughter forever, I would consent. That’s where the memory precipitously stops, at the moment I knew that my answer was meant to be yes, that my subjugation would appease the great injustices he felt had been done to him.

It bores me, it shatters me to understand it, how much of our behavior is just a rejoinder to an old question, like something shouted down the hall at some delay, the hall being all the time we hurried down, the shout being the noise we make once we think we’re safe.

From the distance of age I could nearly see it from above—how, when I was a child desperate to be alone, I had sometimes scrambled along the gossip of a creek. It made me dolorous now, to see those beds of stone where water no longer confided, and in the absence of that sound I listened to others. The tender owl at night, the anxious donkey afternoons. The red rufous hummingbirds who dove blaring through morning, tracing the shape of a j at such speed that their path downward could be mistaken for suicide, and the whir of their wings for some man-made weapon.