Amazon's Monopoly Tollbooth in 2023 - Institute for Local Self-Reliance (original) (raw)

The steep and rapidly growing fees Amazon extracts from the businesses that have little choice but to rely on its site to reach customers are a striking measure of its monopoly power. These exorbitant fees are crushing many sellers, raising consumer prices, and funding Amazon’s expanding empire.

This new issue brief updates data and analysis from our two earlier, more in-depth reports, Amazon’s Monopoly Tollbooth (2020) and Amazon’s Toll Road (2021).

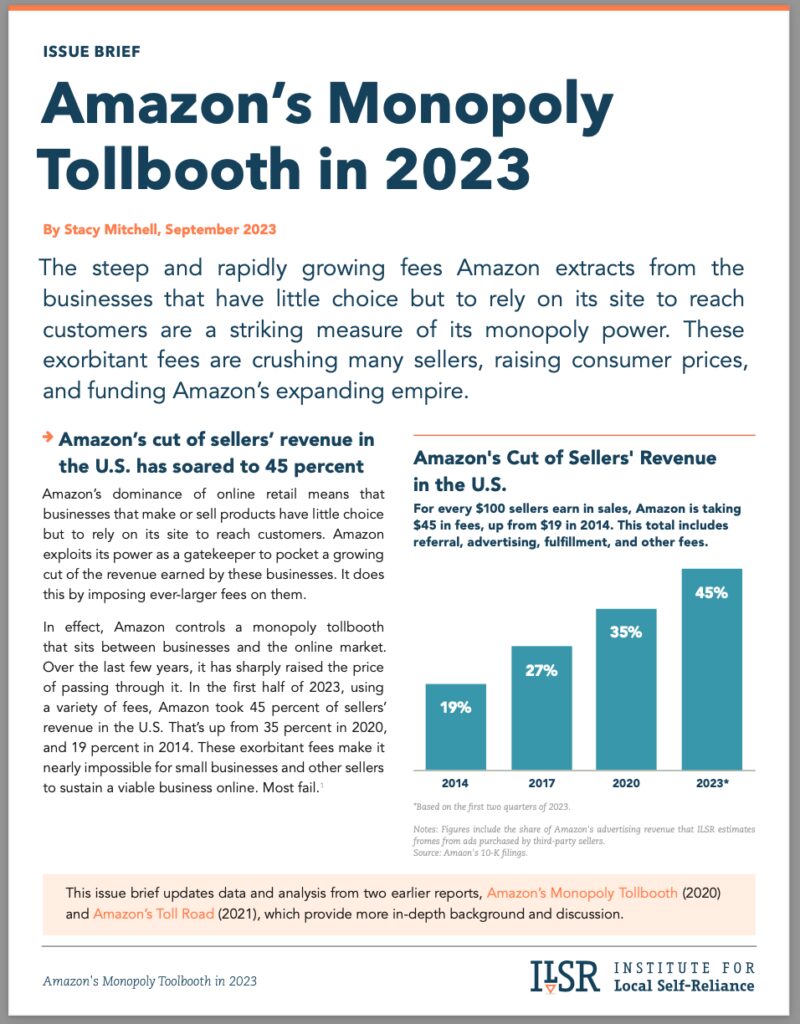

Amazon’s cut of sellers’ revenue in the U.S. has soared to 45 percent.

Amazon’s dominance of online retail means that businesses that make or sell products have little choice but to rely on its site to reach customers. Amazon exploits its power as a gatekeeper to pocket a growing cut of the revenue earned by these businesses. It does this by imposing ever-larger fees on them.

In effect, Amazon controls a monopoly tollbooth that sits between businesses and the online market. Over the last few years, it has sharply raised the price of passing through it. In the first half of 2023, using a variety of fees, Amazon took 45 percent of sellers’ revenue in the U.S. That’s up from 35 percent in 2020, and 19 percent in 2014. These exorbitant fees make it nearly impossible for small businesses and other sellers to sustain a viable business online. Most fail.[1]

Amazon has used “advertising” fees to sharply increase the price it charges sellers simply to list and sell a product.

Amazon’s seller fees take three main forms: referral, advertising, and fulfillment. The referral fee, akin to a commission, is 15 percent for most products. This used to be the main cost of selling an item on Amazon’s site. But a few years ago, Amazon began converting much of the space on its search results pages to paid listings (often under deceptive labels such as “highly rated”).[2] Most sellers have found that they must pay for these spots to continue generating sales. That’s because sellers who decline to buy this ad space not only give up access to the most visible space on Amazon’s search results pages. They also lose their place in the organic search results, because Amazon’s algorithm indirectly favors sponsored products.[3]

Amazon’s seller fees take three main forms: referral, advertising, and fulfillment. The referral fee, akin to a commission, is 15 percent for most products. This used to be the main cost of selling an item on Amazon’s site. But a few years ago, Amazon began converting much of the space on its search results pages to paid listings (often under deceptive labels such as “highly rated”).[2] Most sellers have found that they must pay for these spots to continue generating sales. That’s because sellers who decline to buy this ad space not only give up access to the most visible space on Amazon’s search results pages. They also lose their place in the organic search results, because Amazon’s algorithm indirectly favors sponsored products.[3]

Amazon calls these paid listings “advertising,” but they provide little value for most sellers. In fact, these paid-listings are just a way for Amazon to indirectly hike its commission and keep more of sellers’ earnings for itself. If you combine advertising and referral fees, the average price Amazon charges a business simply to list and sell a product in the U.S. jumped by nearly 50 percent in the last six years, rising from a 15 percent cut of the sale to 22 percent.

Amazon compels sellers to buy its warehousing and shipping services.

The third major component of the tolls Amazon collects from sellers are the fees associated with its warehousing and shipping service, Fulfillment By Amazon (FBA). About 90 percent of the top 10,000 sellers on Amazon use FBA.[4] Why have so many opted for FBA over other carriers like UPS and the Postal Service? Amazon requires sellers to use FBA in order to qualify their items for Prime, without which they have little chance of generating sales. Amazon has thus made a business’s ability to sell products on its marketplace, which dominates online shopping traffic, contingent on buying its warehousing and shipping services.

Over the last few years, Amazon has repeatedly raised the prices it charges sellers to store their inventory and fulfill their orders.[5] It’s also imposed a cascade of onerous new requirements on how sellers manage their inventory across its warehouses, while failing to provide adequate customer support for sellers whose inventory is lost or trapped in Amazon’s systems.[6]

Amazon’s steep tolls are evidence of an illegal monopoly.

In a healthy, competitive market, Amazon’s high prices and poor treatment would lead sellers to go elsewhere. But Amazon uses several monopolistic tactics to thwart competition, trap sellers, and ensure they cannot grow their sales on other sites. For example, Amazon effectively bars sellers from pricing a product for less on another site.[7] If they do, Amazon will tank their sales on its site by demoting the item in search results, deleting its Prime badge, or removing the “buy now/add to cart” option from the product page.

Sellers cannot risk any of these actions. So they keep their prices inflated on other (lower-cost) sites to match those on Amazon. This way Amazon blocks real price competition, maintains its dominance in e-commerce, and preserves its ability to hike seller fees without consequence. In an internal memo obtained by the House Judiciary Committee, an Amazon executive, referencing a round of price hikes for sellers, reported that “seller attrition as a result of fee increases” was “[n]othing significant.”[8] Additional fee increases soon followed.

Amazon’s logistics creates a moat around its monopoly, trapping sellers and preventing them from growing their sales on other sites.

One reason Amazon built a major package delivery operation was to gain another means of controlling sellers and blocking competition in e-commerce. Most sellers would like to lessen their dependence on Amazon and shift more of their sales to non-Amazon channels. Using a neutral shipper to fulfill both Amazon and non-Amazon orders can help enable this. Until 2019, Amazon allowed sellers to manage their own shipping and still qualify for Prime (so long as they met the delivery speeds). But then Amazon canceled “Seller Fulfilled Prime” (SFP), because it knew that sellers with effective multi-channel order fulfillment threatened its dominance in e-commerce. (Under scrutiny, Amazon recently reintroduced SFP, but with new fees that deter its use.)

For many sellers, using two separate fulfillment services is cost-prohibitive. Since they must use FBA to qualify for Prime, many end up using FBA for their non-Amazon orders too. But doing so undermines their ability to grow their sales on other sites, in part because Amazon slows delivery times and charges much higher fees to ship non-Amazon orders. For example, to ship a 13-ounce item purchased on Amazon, sellers pay 3.77,butthecostrisesto3.77, but the cost rises to 3.77,butthecostrisesto8.25 if the item was purchased on another site.

Amazon uses the money it extorts from sellers to subsidize other parts of its business. This allows Amazon to sell some of its own products below cost, which thwarts competition.

We can get a sense of the scale of this cross-subsidy by comparing the fees Amazon gets from its marketplace with its expenses for fulfilling orders. In the first half of 2023, Amazon racked up $82 billion in costs for staffing and operating its fulfillment facilities and shipping products to customers (globally). This figure includes the cost of fulfilling orders for both sides of Amazon’s retail operation: the roughly 60 percent of sales made by third-party sellers and the roughly 40 percent of sales made by Amazon itself.

During the same period, Amazon collected $82 billion in fees from businesses selling and advertising on its shopping platforms (globally). Amazon thus extracted enough revenue from these businesses to cover 100 percent of the cost of fulfilling both their orders and Amazon’s own orders. In other words, Amazon doesn’t have to build warehousing and shipping costs into the price of its own products, because it’s found a way to get smaller online sellers to pay those costs.[9]

Amazon’s tolls function as a hefty tax on businesses selling online. The scale of this tax is massive: Amazon will collect $185 billion in fees from its marketplace in 2023.

Operating a monopoly tollbooth that sits between businesses and their customers is wildly lucrative for Amazon — and a major drain on companies selling goods online, many of whom struggle to survive under the burden of Amazon’s fees, much less to invest in new products and growth.

This year, Amazon is on track to take in a staggering 185billioninfeesfromitse−commerceplatform.That’stripleitstakein2019,whenAmazon’smarketplaceyielded185 billion in fees from its e-commerce platform. That’s triple its take in 2019, when Amazon’s marketplace yielded 185billioninfeesfromitse−commerceplatform.That’stripleitstakein2019,whenAmazon’smarketplaceyielded66 billion in fees. And it’s more than fourteen times the revenue of 2014, when marketplace fees were about $13 billion.

The 185billionprojectedforthisyearincludesnearly185 billion projected for this year includes nearly 185billionprojectedforthisyearincludesnearly125 billion siphoned from third-party sellers serving the U.S. market (adding together what they pay in referral, advertising, and fulfillment fees), roughly 45billioninfeesfrombusinessessellinginforeignmarkets,andaround45 billion in fees from businesses selling in foreign markets, and around 45billioninfeesfrombusinessessellinginforeignmarkets,andaround15 billion in ads purchased by vendors that sell directly to Amazon.

Half of Amazon’s revenue now comes from controlling the infra-structure other companies depend on to transact sales and data.

For much of Amazon’s history, people thought of it as a retailer. But all along, its founder, Jeff Bezos, was building something else entirely: a corporation that would control the essential infrastructure that other firms depend on to sell and transmit goods, services, and data. This would enable Amazon to set up tollbooths across the economy and collect a tax on a large swath of economic activity.

For much of Amazon’s history, people thought of it as a retailer. But all along, its founder, Jeff Bezos, was building something else entirely: a corporation that would control the essential infrastructure that other firms depend on to sell and transmit goods, services, and data. This would enable Amazon to set up tollbooths across the economy and collect a tax on a large swath of economic activity.

Bezos’s ambition has become a reality. Back in 2014, Amazon derived nearly 80 percent of its revenue from selling products. The fees it collected from companies relying on its e-commerce infrastructure (Marketplace) and cloud infrastructure (Amazon Web Services) generated 17billion,orlessthan20percentofitsrevenue.Thisyear,thesetollswillbringinalmost17 billion, or less than 20 percent of its revenue. This year, these tolls will bring in almost 17billion,orlessthan20percentofitsrevenue.Thisyear,thesetollswillbringinalmost280 billion and account for nearly half (49 percent) of Amazon’s revenue. Marketplace fees alone will make up one-third of the tech giant’s topline.

Seller fees likely generate far more profit for Amazon than AWS does.

It’s widely assumed that Amazon derives most of its profits from its cloud division, AWS. But there’s good reason to believe that seller fees are an even bigger source of profit than AWS. We can’t know for sure because Amazon does not report its profits from seller fees in its quarterly financials (and, when asked by a Congressional committee to disclose these figures in 2020, Amazon declined.)

If we assume Amazon’s profit margin on marketplace fees is 30 percent — which seems conservative given that half these fees are for digital ads and commissions that create virtually no marginal cost for Amazon — then, in 2022, Marketplace fees may have generated roughly twice the profits ($46 billion) of AWS ($23 billion).

How then did Amazon end up reporting losses of about $11 billion on its e-commerce operations in 2022? As noted above, Amazon uses the income from sellers to subsidize below-cost selling, a predatory tactic that keeps other retailers from effectively challenging its dominance. In its financial reports, Amazon adds these losses to its profits from seller fees, so each cancels out the other, effectively concealing the scale of both its monopoly rents and its predatory pricing.

If you like this post, be sure to sign up for the monthly Hometown Advantage newsletter for our latest reporting and research.

[1] Amazon is a constant churn of sellers, as retailers and product-makers try and often fail under the crushing weight of Amazon’s fees. Over time, Amazon has increasingly turned to sellers based in China, who now account for about half of the top 10,000 sellers on its U.S. Marketplace, according to Marketplace Pulse.

[2] Annie Palmer, “Amazon is piling ads into search results and top consumer brands are paying up for prominent placement,” CNBC, Sept. 19, 2021.

[3] This is because Amazon’s search algorithm favors products with more sales. As more orders are driven by ads, sellers than don’t advertise lose out on those sales and, as their share of sales declines, they also slip in the search rankings, further reducing their sales in a negative cycle.

[4] Marketplace Pulse, “Marketplace Pulse Year in Review 2022.”

[5] Stacy Mitchell, Ron Knox and Zach Freed, Amazon’s Monopoly Tollbooth, Institute For Local Self-Reliance, July 28, 2020, at 11.

[6] Sebastian Herrera, ”Amazon Overhauls Delivery Network to Dispatch Packages Faster, More Cheaply,” Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2023, Kiri Masters, “Amazon Hobbles Merchants’ Prime Day Preparations With Inventory Restrictions,” Forbes, May 27, 2021.

[7] “Amazon Marketplace Fair Pricing Policy,” available at https://sellercentral.amazon.com/gp/help/external/G5TUVJKZHUVMN77V, (last visited Sep. 15, 2023). Also see:

Superior Court of the District of Columbia. District of Columbia v. Amazon.com, Inc., Karl A. Racine, Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia, 2021.

[8] “Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets,” U.S. House Judiciary Committee, 2020, at 274.

[9] Amazon doesn’t disclose how exactly it uses the revenue it gleans from sellers. This money may fund its shipping costs for its own retail sales, as we discuss here, or something else, such as acquiring other companies and building facilities. One way or another, though, it provides a major cross-subsidy that funds Amazon’s strategies for market dominance. Our comparison to Amazon’s warehousing and shipping expenses is a way to understand the scale of this cross-subsidy.