Chapter VI - Shark Alley - The Jack Vincent Papers Vol 1 (Grave) (original) (raw)

The machine people continued, nevertheless, to toil. They had rescued what assets they could from the shop without arousing suspicion, and they set about working from home. My father now took the long walk to the market, and I began my apprenticeship. The work was hard on the eyes and the fingers, but I took to it readily enough for I had watched my father labour for years. I enjoyed the precision of measuring, cutting, felling and hand stitching, and loved losing myself making buttonholes or embroidering, hours passing without my notice as I sewed. This was a calm, meditative state that I have rarely, if ever, achieved since as an author. It felt good to be active within the process of mending the family. As we all worked, day and night, we began to stitch the family back together. As the arrival of the new baby approached, the machine people grew softer again, and I knew that my parents had returned, changed, it was true, by their experiences, wherever they had been (I was not going to ask), but fundamentally themselves again. For a while at least, the shadow receded.

My father still made time for me as well, even if our elementary entertainments cost him dear in terms of the extra hours he had to work before dawn to catch up. His love of stories appeared returned, and I had contrived the plan of enacting a simple play to celebrate my mother’s forthcoming birthday, which fell upon All Hallows’ Eve. My father thought this a capital idea, and agreed to not only assist with costumes but to act alongside me.

Given the influence I was later to have on the popular stage, it was in every way appropriate that I begin my authorial career in my twelfth year with a little gothic melodrama called ‘The Gold Tooth.’ We were compelled to rehearse out of doors in the biting cold, but after a few turns we had quite got the thing down.

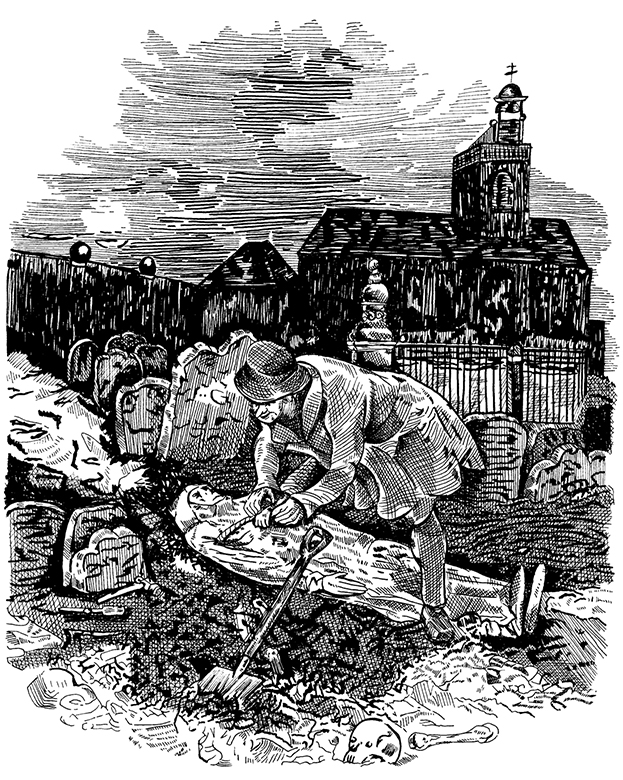

We set up behind the curtains dividing the parlour from the kitchen. For a backdrop, we had painted the silhouettes of gravestones on an old sheet, using dyes from the shop to simulate a night sky. A plank borrowed from the woodshed propped upon its leading edge in the foreground served as the side of a coffin, my father lying behind it playing the corpse, and a pile of sacks sprinkled with dirt from the garden implied a mound of freshly turned earth. I took the leading role of ‘Fulgentius,’ a common country sexton by day, but by night a notorious resurrection man known only as the ‘Snorter’ on account of his huge nose, and his habit of taking snuff ground from coffins and human bones. I was armed with the garden spade, and wearing a scarlet cloak made from an old curtain. Long lank hair was fashioned from floured wool, my face rendered sharp and wicked by virtue of a cardboard snout of exaggerated length and girth, more flour, and a grinning mouth drawn roughly in rouge pinched from my mother’s dresser. By candlelight the effect was striking. My mother was our sole audience, seated upon a dining chair at the far end of the parlour.

The story opened with a thunderstorm, establishing mood and symbolising the inner processes of the villain. In my later ‘Newgate’ period, the apocalyptic storm became something of a trademark, and that insufferable prick Thackeray used to lampoon me about it something chronic. In this case, the dramatic affect was achieved by my father wobbling a wood saw before the curtain was raised, while I whacked a partially shielded lantern hung out of sight above my head during the performance.

In the opening scene, Fulgentius digs by lantern light, exhuming the corpse of the investment banker ‘Magnus,’ recently deceased from shock upon being presented with a bill from his wife’s dressmaker. ‘When did any man’s heir feel sympathy for his decease?’ he soliloquises. ‘When did his widow mourn? When doth any man regret his fellow? Never! He rejoiceth. He maketh glad in his inmost heart. He cannot help it, for it is in our nature. We all delight in each other’s destruction. We were created to do so; or why else should we act thus? I never wept for any man’s death, but I have often laughed.’ At this point he raps his shovel on the top of the coffin (the floor) and exclaims, ‘By the old gods of England that’s pay dirt! Here is a coffin in an exquisite state of decay. It’ll scarcely require any grinding to make excellent snuff.’

He pauses to produce a snuffbox (my father had a tin one full of pins in a workbench drawer which he had generously loaned), and I made comic play of snorting a huge pinch, followed by a long-builded, harlequinesque sneeze.

‘My heavens, but that’s strong stuff,’ says he, ‘this must be the batch I made up from the judge. He needed no embalming; he was pickled and preserved long since.’ He examines the corpse, lowering the plank to its side, revealing my father lying in state in his best clothes, his face made cadaverous with ash from the fireplace and trying not to laugh. ‘Ah, Mr. Magnus. You once refused me a loan, but what’s that you say?’ He leans close, ‘You’ve reconsidered. A wise and generous choice, sir! No need for paperwork I’ll be bound, I’ll just take it now if I may.’ He begins to rifle the corpse’s pockets. ‘What’s this? You didn’t take it with you? Mr. Magnus I am shocked! Was it that pretty young wife of yours? You left it all to her? Egad sir! She’s left you nothing but the fillings in your teeth. You’ll never pay the ferryman at this rate, but what banker ever pays his way like an honest man? You’ll have some speculation in mind I expect, a sound investment overseas, if only Charon will put up some modest collateral, his little house in the Styxx perhaps. Well, no matter, I’ll take these handsome gold caps upon your choppers, and the surgeon will make up the rest.’

He tries to remove the front teeth, allowing for several seconds of slapstick as he attempts different methods of extraction, bracing his foot on the banker’s chest and pulling. At last, breathing heavily, he produces a large pair of pliers from a poacher’s pocket and removes the offending ivories. I had motes of gravel in my palms and appeared to scrutinise extracted teeth, before pocketing a couple and discarding the rest, which rattled very satisfactorily along the floor.

The shock of this injury wakes the corpse, who was not dead at all but in a cataleptic trance. (We had in advance blackened out my father’s front teeth with boot polish.) He sits up and addresses the body snatcher in a state of some confusion. ‘Are you angel or devil?’ says he.

‘I am neither, sir,’ says Fulgentius, ‘I am merely an honest tradesmen going about his business. Now kindly resume your place that I might continue in my work.’ He tries to push the banker back into the coffin with his booted foot.

‘Oh unhappy happenstance,’ moans the banker, ‘it is clear to me that I am in the abode of the Unholy One.’

‘And what did you expect?’ rejoins Fulgentius. ‘You grow rich with neither talent nor trade, you contribute nothing to society, yet you reward yourself with a king’s ransom in wages, and if your bank should fail you still turn a profit. Then you presume upon the shareholders of your next venture to bestow upon you a bonus, for your business experience is such a valuable asset to the corporation, and must be rewarded according to scale that you and your fellows set yourselves. Surely the last truly fine idea the Devil had after the seven deadly sins was speculative finance!’

‘But the empire requires a strong economy,’ says the banker, ‘which my colleagues and I underwrite. To be in financial services is truly a patriotic calling.’

‘Such insouciance,’ says Fulgentius. ‘You make me feel a clean and decent man in comparison! Now I’ll to my patriotic exertions. I provide a true public service, you old usurer, for how could surgeons study anatomy if they could not dissect the likes of you? How could they perform operations on the living? They’ll find no heart in there, I’ll be bound, but I’m sure the other bits’ll be of some interest.’

He raises his shovel to strike a fatal blow, but the corpse springs up, pushes him aside and legs it stage left. Fulgentius calls after him: ‘Stop, ghost! Stop, body! Watch! Watch!’ He appeals to the audience for support. ‘The natural order of life, death and commerce has been transgressed. That man is my property. I am natural guardian of the churchyard, and he must come back and be sold and dissected like an honest Christian, or I’ll get a warrant.’ He shakes his head sadly. ‘I shall be ruined. If the other bodies should learn this trick, and walk off too, what shall I do? I shall never have any more business.’ He becomes more agitated, appealing now to the heavens. ‘I’ll be hanged if I’ll be bilked in this manner. I’ll after him, and claim him wherever I find him. I’ll get a search warrant, and an officer.’ He too runs off stage crying, ‘Watch!’ as the curtain falls.

In the shorter second act, the banker has made his way home (the backdrop was now a plain sheet with a window painted on it), only to discover his supposedly grief-stricken wife already in the arms of his best friend. This is done in the form of a diegesis, the revenant emoting in the direction of events only he can see. He dives offstage and loudly murders both wife and lover, flinging body parts of my father’s manufacture across the stage, decorated with red silk to affect torn and bloody skin.

Fulgentius then arrives declaring, ‘Zombi bankers I doubly hate!’ before braining Magnus with his shovel. The curtain falls as the sexton sings a variation of an old pewter woggler’s bangling song, celebrating his new found fortune of three corpses and all their cash and jewellery:

‘How merrily lives a grave digger.

He sings as he shovels away!

His purse was light, but his spade was bright.

Now he cavorts both night and day!’

The cast then took the curtain call to enthusiastic applause, after which there was cake.

For a pious woman, my mother loved a good gothic tale as much as my father and myself, and she subsequently bade me transcribe my little play in the form of a short story. I was delighted to oblige, and felt it came out fairly well. I have never really been one for drama to be honest (poetry neither), and much prefer the ebb and flow of narrative prose, as anyone who has experienced my attempts at the latter classes will no doubt attest. But we cannot all be good at everything, and it is a wise man indeed, I have always felt, who is mindful of his limitations.

*

In a cruel inversion of life and nature that I have nowadays come to expect, Christmas that year was as terrible as Halloween had been grand. Whereas Dickens always delighted in pushing this tiresome ritual down everyone’s throat, it has always infused my soul with the most profound sorrow, for if something bad happens on a red letter day then you must re-live it annually while the general population celebrates idiotically around you. The Yuletide festival does not, therefore, represent the Nativity of our Lord and Saviour or goodwill to all men in my heart so much as it does the agonising death of my mother in childbirth.

In a cruel inversion of life and nature that I have nowadays come to expect, Christmas that year was as terrible as Halloween had been grand. Whereas Dickens always delighted in pushing this tiresome ritual down everyone’s throat, it has always infused my soul with the most profound sorrow, for if something bad happens on a red letter day then you must re-live it annually while the general population celebrates idiotically around you. The Yuletide festival does not, therefore, represent the Nativity of our Lord and Saviour or goodwill to all men in my heart so much as it does the agonising death of my mother in childbirth.

The memory haunts me still. The labour seemed to have no end; and while she pushed and sobbed and prayed and screamed and panted through the limitless night, I repeatedly and mechanically dampened and applied a flannel to my poor mother’s brow in between her body’s violent contractions as if in a trance. The midwife alternately cooed in encouragement or bellowed orders, periodically listening for the infant’s heartbeat with a small ear trumpet. My father, meanwhile, gripped his wife’s hand and silently mouthed a continuous and hopeless prayer.

The child would not come. After the worst night I had ever lived (God alone knew what torture it was for my dear mother, if God there was), the midwife finally took my father aside and asked, ‘Might I at least save the child?’

He wept and raged until my mother stared him down and pleaded without words that she be set free and the baby delivered safely. He finally acquiesced, and I was sent from the room. Although I blocked my ears with my balled fists I still heard the sliding scrape of a blade on stone, and then her animal screams as they killed her. Next there came a new-born’s cries, soon to be drowned by the desolate howls of my father. Time paused, as I have heard it does the instant before a cannon shell explodes amongst a group of unlucky soldiers, then he burst from the charnel room like an assassin discovered and fled into the frozen dawn, growling obscenities as if possessed by some demon.

The gory fingersmith followed, carrying my tiny sister in a bloodied rag. ‘You’ll need a wet nurse,’ she said, casually handing me this little dab of humanity. ‘Mrs. McGuire’ll probably oblige,’ she advised, ‘if the money’s right.’ She spoke not a word of condolence, the old bitch, for in the spirit of the times she was all business. She quickly took her leave, registering in no uncertain terms her irritation at the fact that my father had quit the cottage without leaving her fee. ‘If he does away with himself,’ said she, ‘I’ll still expect reparation.’

I numbly agreed that I would see her all right, and showed her to the door. And that was how my sister Sarah entered the world.

I knew not what to do with the shivering, screaming thing in my hands, but placing a finger in her tiny mouth seemed to placate her. I wrapped her in a spare shirt and made my way across the muddy fields to the McGuire’s cottage. The butcher had become a farm labourer, so I knew the family would be awake even at that godforsaken hour. Mrs. McGuire was a deal more sympathetic than the midwife, and insisted I take a drop of the creature to soothe my shattered nerves while she attended to the baby behind a curtain. She gave me some gin and hot water, with a few drops of laudanum in it. I was too exhausted to protest on religious grounds and past caring anyway, and this was in consequence my first taste of strong drink and the peace that it temporarily brings to the soul. I have heard tell of youngsters who spewed their insides out after a single swig and never touched another splash, but I was not so fortunate. I took to that liquid darkness from the first, with a pleasure for the bottle matched only by my sister’s lust for Mrs. McGuire’s pendulous dugs.

I was drunk by the time I returned home, having left the baby with that goodly woman until some sort of nursing arrangement could be formalised. She assured me that after ten of her own, all still kicking, she knew what she was doing, and that she further knew that my father would be good for the reckoning when things settled down. I should be brave, she said, attend to my mother, and try not to worry. I was not so intoxicated as to believe that things would ever settle down again, but I had nowhere else to go but back to the cottage.

My father had not returned. The low winter sun suggested it was the afternoon, but I was not exactly sure for the clock had wound down. I wanted more drink, but had to settle for icy well water, which to a certain extent at least restored me to my senses. It was as cold as the grave, so I made up a fire and boiled water for tea, not yet quite able to banish the routine by which I would normally prepare a cup for my mother. That was when the nerveless shock of the morning finally gave way to a profound grief and I sat and cried out my heart like the child I still was. I know not what, but something within must have broken then, for I have not shed a tear since, neither in pain, rage, sadness or passion. I believe that the dark world got in that day, for when I composed myself my first thought was to go to my mother. God help me, I wish it were true that I wanted to clean her and lay her out before my father’s return, but in my soul I knew that more than anything else I wanted to see the corpse. I had to see the corpse.

The room stank. I knew not until that moment that a human being was no more than blood and shit, a putrid sludge that had not only soaked into the horsehair of the mattress but had sweated its way into the very walls. No attempt had been made to cover her in her murderers’ indecent haste to quit the scene. It had obviously been an inexpert operation, and she looked as if she had died trying to scramble uselessly away from the pain. Her head was flung back, and the language of her body still told a tale of unimaginable agonies endured for the sake of her child, because there was no other way, and because no one could undertake that final trial but she. Her nightdress had been raised and her swollen belly had been slit from the centre of her breasts to her private parts, and the flesh and fat pulled aside that the child could be snatched from the uterus, leaving an obscene crimson cavity. Her skinny white legs were splayed wetly like those of some grossly violated rag doll, while her delicate hands were as claws, locked in a final, fatal grip upon sodden and twisted sheets. She looked more like a butchered sow than a human woman, save for her face, which was not in repose, as I had been told the dead looked, but instead frozen in her last moments of pain and horror, her wild eyes staring blindly, her mouth wide and her teeth barred in mute protest at such an ugly, pointless, and untimely death.

I stared deep into those dry, dead eyes and I saw no God there, no final, fleeting glance that denoted any recognition of salvation in my mother’s final breath. All I saw was darkness.

Click here to read Chapter VII