Pioglitazone increases non-esterified fatty acid clearance in upper body obesity (original) (raw)

Introduction

Insulin resistance is commonly present in upper body obesity [1–3] and type 2 diabetes [4, 5]. This is manifested by impaired glucose disposal and increased plasma NEFA concentrations. Plasma NEFA concentrations are largely determined by effective adipose tissue lipolysis, as assessed by measurements of NEFA release [6], but are also regulated by NEFA clearance [7, 8]. Lipolysis is abnormally increased under both basal [3] and insulin-suppressed conditions [3, 9] in upper body obesity and type 2 diabetes [4, 5]. The resultant higher NEFA concentrations [7] are thought to contribute to insulin resistance at the level of muscle [10, 11] and liver [12], to hypertriglyceridaemia [13] and to abnormal vascular function [14]. The ability of insulin to suppress plasma NEFA concentrations following meal ingestion is thought to play an important role in peripheral glucose disposal [10] and suppression of hepatic glucose release [12]. Thus, the effects of diabetes treatment agents on postabsorptive and insulin-suppressed NEFA are of equal interest.

Interventions that reduce insulin resistance also improve the metabolic abnormalities associated with upper body obesity [15] and enhance glucoregulation in type 2 diabetes. Examples include diet/exercise and thiazolidinediones [16]. Thiazolidinediones, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists, have been reported to enhance the insulin suppression of lipolysis in type 2 diabetes [17–20]; this could account for the improved insulin regulation of glucose disposal seen in response to thiazolidinediones.

Imputing basic physiological actions of thiazolidinediones from their effects in type 2 diabetes is confounded by the effects of improved glycaemic control on insulin action. Lowering plasma glucose concentrations in type 2 diabetes improves insulin action with respect to glucose metabolism, even when insulin is used as the treatment [21]. Although similar studies do not appear to have been conducted with respect to NEFA metabolism in type 2 diabetes, there are reports that in vitro lipolysis of human fat cells is affected by variations in extracellular glucose [22, 23]. To avoid potential confounding by disparate improvements in diabetic control with different treatments, we examined the physiological effects of pioglitazone on fatty acid metabolism in non-diabetic men and women with upper body obesity, in whom insulin regulation of NEFA metabolism is known to be abnormal [3, 9]. To determine whether any observed effects were specific to pioglitazone, or could be reproduced non-specifically via another means of insulin sensitisation, we also studied a comparable number of volunteers before and after diet/exercise-induced weight loss.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Subjects are the same as those reported in a recent publication of the effects of pioglitazone vs diet/exercise on body fat distribution and insulin sensitivity [24]. As part of this study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board, we obtained written informed consent from 45 non-diabetic, upper body obese men and premenopausal women with a BMI of 28–36 kg/m2. Subjects were sedentary (participating in no regular recreational exercise activities) and were weight-stable for at least 6 months before entering the study. Further inclusion criteria consisted of either a fasting plasma glucose of 5.5–6.9 mmol/l or at least two of the following: (1) WHR >0.85 (women) or >0.95 (men); (2) visceral fat area measured by computed tomography (CT) >120 cm2 (women) or >180 cm2 (men); or (3) CT-measured visceral:total fat ratio >0.30 (women) or >0.40 (men). Exclusion criteria were a history of coronary heart disease, atherosclerosis or systemic illness; biochemical evidence of renal or liver failure; blood pressure >160/90 mm Hg; use of medication that could not safely be discontinued 2 weeks before the study; smoking; pregnancy; and breast-feeding.

Six women dropped out after completing the pre-intervention study for a variety of reasons, only one of which was treatment-related (angioneurotic oedema after pioglitazone [25]).

Study protocol

The volunteers were assigned to the diet/exercise or the pioglitazone arm and to the insulin clamp or the saline study protocol using a block randomisation approach that was designed to achieve equal numbers of men and women in the different arms/study types. After baseline testing (body composition, complete blood count, chemistry panel, lipid profile, intravenous glucose tolerance test [24]), volunteers consumed an isocaloric diet for 1 week (50% carbohydrates, 35% fat, 15% protein). The volunteers were then admitted to the Mayo General Clinical Research Council (GCRC), where a blood sample was collected for background plasma oleate specific activity (SA) and glucose enrichment. At 06.00 hours the next morning, an infusion of [6] glucose (0.06 mg kg−1 FFM min−1) was started to trace glucose kinetics, followed by a [9, 10-3H]oleate (29 kBq/min) infusion at 08:00 hours. In 19 volunteers, a hyperinsulinaemic (1.0 mU kg−1 FFM min−1)–euglycaemic clamp was started at 08:00 hours using [6-2H2]glucose-labelled 50% dextrose; the other 20 participants received a saline infusion. The particular dose of insulin used for this study was chosen because it is in the mid-physiological range (comparable to plasma insulin concentrations obtained following meal ingestion) and to be sure that moderate changes in glucose and NEFA responses to insulin could be detected if they occurred. The specific duration of the insulin clamp was chosen to be sure that a new steady-state respiratory exchange ratio would be achieved in the insulin clamp group to accurately measure substrate oxidation. Blood samples were obtained at 10-min intervals between 13:30 and 14:00 hours for the measurement of plasma hormone and catecholamine concentrations, plasma oleate levels and glucose flux rates. Indirect calorimetry was performed at 13:30 hours with a DeltaTrac Metabolic Cart (Yorba Linda, CA, USA). Urine was collected for measurement of nitrogen excretion throughout the study.

The volunteers were subsequently randomised to undergo either a diet/exercise programme or pioglitazone treatment (30 mg daily) for 18–20 weeks [24], after which time the pre-intervention studies were repeated. The weight-loss programme consisted of a diet designed to induce a 500-kcal/day deficit (55% carbohydrates, 30% fat, 15% protein), an aerobic exercise programme and biweekly behaviour-modification instructions (modified LEARN programme [26]). Following treatment initiation, the pioglitazone group continued their previous lifestyle (with respect to diet and physical activity) and were monitored every 4 weeks for body weight, liver function tests and pill counts. The post-intervention studies for each volunteer were identical to their pre-intervention studies, including the documentation of the weight-maintaining diet (by daily GCRC weights) for 1 week prior to their post-intervention assessments.

Analysis of plasma samples

Glucose: glucose analyser (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA); glucose enrichment: gas chromatography/mass spectrometry [27]; insulin, C-peptide and growth hormone concentrations: chemiluminescent sandwich assays (Sanofi Diagnostics, Chaska, MN, USA); catecholamines: HPLC with electrochemical detection [28]. Plasma oleate concentrations and SA, as well as total NEFA concentrations, were measured by HPLC [6]. Plasma triglyceride concentrations were measured using a centrifugal auto-analyser [29], and plasma triglyceride SA was measured by extracting the lipids from plasma using standard techniques [30] and then specifically isolating and measuring the radioactivity in the triglyceride using a HPLC-based approach [31]. We corrected for incomplete recovery by measuring the glycerol concentration in a hydrolysed aliquot of the triglyceride HPLC fraction. This method allowed us to measure the specific concentration of 3H-labelled triglyceride in plasma (dpm/ml), irrespective of the presence of other 3H-labelled compounds (3H2O, [3H]oleate, etc).

Calculations

NEFA flux is the amount of fatty acid released into the circulation via adipose tissue lipolysis and taken up by tissues per time unit. At steady-state, the rate of NEFA release is equal to NEFA uptake. In these studies we specifically measured oleate, the major NEFA in plasma, as the indicator of NEFA flux.

Steady-state plasma oleate (and NEFA) concentrations and SA were achieved in each study. Steady-state rates of appearance (Ra) and disappearance (Rd) of oleate and glucose were calculated using the mean SA or enrichment values and tracer infusion rates [3, 27]. Endogenous glucose production during the insulin clamp was calculated by subtracting the exogenous glucose infusion rate from total glucose appearance. Oleate clearance (l/min) was calculated by dividing oleate Rd (μmol/min) by oleate concentration (μmol/l). Because the groups were well matched in terms of resting energy expenditure (REE) and fat-free mass (FFM) the oleate flux data are presented as μmol/min rather than dividing by units of weight or body composition [7]. Matching for relevant variables is preferable to using numerator/denominator approaches to present NEFA flux data because it prevents drawing spurious conclusions [32]; NEFA flux is most strongly predicted by REE [7]. Substrate oxidation was assessed using CO2 production relative to O2 consumption rates and urinary nitrogen excretion [33].

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means±SEM. Statistical comparisons between men and women in the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups before and after interventions were performed using a 2×2×2×2 repeated-measures ANOVA with factors for sex (men vs women), group (diet/exercise vs pioglitazone), study (saline vs insulin clamp) and time (pre- vs post-intervention). If statistically significant differences were found, follow-up non-paired or paired t tests were performed. If the direction of the difference was predicted from the literature (for example, insulin-stimulated glucose disposal increasing with diet/exercise or pioglitazone), a one-sided _t_‐test was used instead of a two-sided comparison. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. We applied a Bonferroni correction when multiple comparisons were made that were not part of the initial plan for statistical analysis.

Results

Subject characteristics

As reported in our previous study [24], the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups had similar baseline, anthropometric, biochemical and metabolic parameters (Table 1). After the diet/exercise programme, weight (−11.7±3.2 kg), body fat (−9.3±0.9 kg) and visceral fat (−2.5±0.3 kg) decreased (p<0.001). After pioglitazone treatment, body weight increased (+2.7±0.7 kg, +1.3±0.4 kg of fat, both p<0.01) but visceral fat mass did not (4.4±0.4 vs 4.3±0.4 kg). Serum triglyceride concentrations decreased after diet/exercise (1.8±0.3 vs 1.1±0.1 mmol/l, p<0.01), but not after pioglitazone (1.9±0.2 vs 1.8±0.2 mmol/l, _p_=0.10). Diet/exercise, but not pioglitazone, decreased REE in women (Table 2); however, REE was similar in the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups, both before and after the interventions. The initial haematocrit in the pioglitazone group was 39.6%, and had decreased to 38.2% (p<0.001) at the time of the second study. The haematocrit in the diet/exercise group decreased from 39.2% to 38.7% (_p_=0.06).

Table 1 Subject characteristics

Plasma glucose, hormone and catecholamine concentrations

Plasma glucose, insulin and C-peptide concentrations were comparable in the two treatment groups and in the men and women at baseline [24], and decreased significantly following intervention. Table 3 shows the plasma insulin, growth hormone and catecholamine concentrations during the NEFA flux measurements.

Table 3 Plasma hormone and catecholamine concentrations

Glucose kinetics

Because there were no significant differences in FFM or REE between the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups before or after the intervention, glucose kinetic values are presented in μmol/min (Table 4). However, for easier comparison with other work, glucose flux values are given in μmol kg−1 FFM min−1 below.

Table 4 Substrate kinetics

In the saline group, neither pioglitazone nor diet/exercise changed glucose flux (pre-intervention: 11±1 vs 11±1; post-intervention: 11±1 vs 12±1 μmol kg−1 FFM min−1, respectively) or oxidation (Table 4). Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal increased after diet/exercise (30±2 vs 39±4 μmol kg−1 FFM min−1, pre- vs post-intervention, _p_=0.007), as did glucose oxidation (_p_=0.002) and the glucose infusion rate required to maintain euglycaemia (_p_=0.004). After pioglitazone, insulin-stimulated glucose disposal increased significantly (from 26±3 to 33±4 μmol [kg FFM−1] min−1, _p_=0.03), whereas the increases in glucose oxidation (_p_=0.08) and the glucose infusion rate (_p_=0.19) were not statistically significant. Endogenous glucose production during the insulin clamp was not significantly changed by diet/exercise (4±1 vs 5±2 μmol kg−1 FFM min−1, pre- vs post-intervention, _p_=NS) and was actually increased following pioglitazone treatment (3±1 vs 6±2 μmol kg−1 FFM min−1, pre- vs post-intervention, _p_=0.03).

We calculated the hepatic insulin resistance index [34, 16] (endogenous glucose production in mmol/min × plasma insulin concentrations in μU/ml) to estimate the ability of fasting plasma insulin concentrations to limit endogenous glucose production in our volunteers. There was an improvement in both the diet/exercise group (6.6±1.1 vs 3.5±0.3, pre- vs post-intervention, _p_=0.006) and the pioglitazone group (9.9±2.4 to 7.4±2.4, _p_=0.006). There was no significant change in this index for either group under insulin clamp conditions.

Oleate kinetics

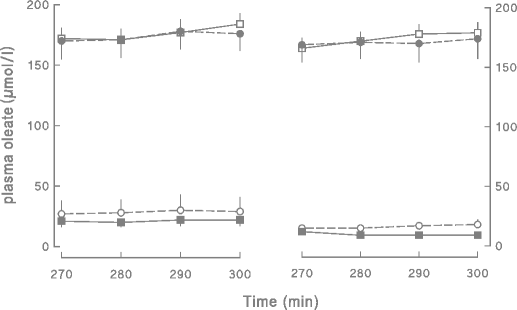

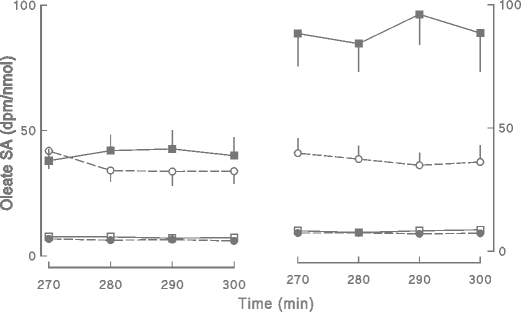

Plasma oleate concentrations and SAs for the different groups and different studies are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. For the saline-infused volunteers, plasma oleate concentrations averaged 174±10 and 166±13 μmol/l (total NEFA concentrations of 536±28 and 533±40 μmol/l) in the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups, respectively, before the interventions. After both diet/exercise and pioglitazone, plasma oleate concentrations were essentially unchanged at 174±8 and 165±9 μmol/l, respectively (total NEFA concentrations of 517±31 and 527±30 μmol/l). The average oleate concentrations are presented in Fig. 3; oleate as a percentage of total NEFA did not differ between groups or between the pre- and post-intervention studies. Oleate flux did not change significantly after either diet/exercise (166±13 vs 149±8 μmol/min, pre- vs post-intervention) or pioglitazone (159±14 vs 176±17 μmol/min, pre- vs post-intervention).

Fig. 1

The plasma oleate concentrations over the last 30 min of the insulin clamp or control saline infusion in volunteers treated with diet/exercise or pioglitazone are depicted. Values obtained prior to beginning treatment (pre-intervention) are shown on the left and those observed after treatment (post-intervention) are shown on the right. Empty squares diet/exercise group-saline, filled squares diet exercise group-clamp, filled circles pioglitazone group-saline, empty circles pioglitazone group-clamp

Fig. 2

The plasma oleate SAs over the last 30 min of the insulin clamp or control saline infusion in volunteers treated with diet/exercise or pioglitazone are depicted. Values obtained prior to beginning treatment (pre-intervention) are shown on the left and those observed after treatment (post-intervention) are shown on the right. Empty squares diet/exercise group-saline, filled squares diet exercise group-clamp, filled circles pioglitazone group-saline, empty circles pioglitazone group-clamp

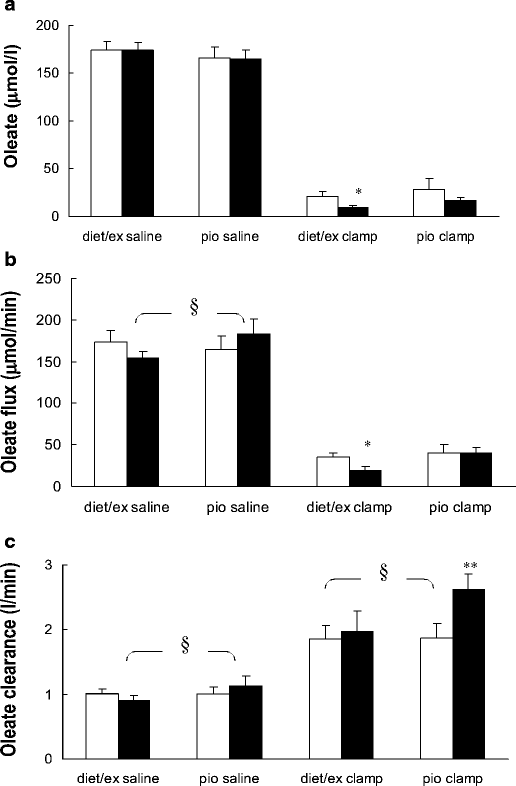

Fig. 3

Oleate concentration (a), flux (b) and clearance (c) under the saline and hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp conditions. Values for those volunteers treated with diet and exercise (diet/ex) and pioglitazone (pio) are presented separately by condition. Pre-intervention values are depicted by open bars and post-intervention values are shown as solid bars. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs baseline; § p<0.05 between interventions. In the pioglitazone-treated group during the saline infusion oleate clearance increased (_p_=0.05, paired t test) from pre- to post-intervention

In the insulin clamp group the pre-intervention plasma oleate concentrations were 21±5 and 33±5 μmol/l (_p_=NS) for diet/exercise and pioglitazone, respectively (total NEFA concentrations of 70±16 and 99±37 μmol/l). Oleate concentrations decreased by ∼50% during hyperinsulinaemia in both the diet/exercise (9±2, p=0.02 for pre- vs post-intervention) and pioglitazone group and (17±3 μmol/l, _p_=0.13 for pre- vs post-pioglitazone) following treatment. The corresponding NEFA concentrations were 33±5 and 60±11 μmol/l in the diet/exercise group and pioglitazone group, respectively. In the diet/exercise group, oleate flux during the insulin clamp decreased from 33±5 μmol/min pre-intervention to 18±4 μmol/min post-intervention (_p_=0.03). In the pioglitazone group, oleate flux was 39±9 and 39±6 μmol/min before and after the intervention, respectively.

Because of the discordant changes in oleate concentrations and fluxes, we analysed oleate clearance changes in the two groups. The repeated-measures ANOVA indicated an overall significant (_p_=0.006) between-group (diet/exercise vs pioglitazone) difference in oleate clearance. By ANOVA the change in clearance between the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups was statistically significant for both the saline control participants (_p_=0.02) and the insulin clamp participants (_p_=0.003). Pre-intervention oleate clearance in the saline control studies was 0.97±0.07 l/min in the diet/exercise group and 0.97±0.10 l/min in pioglitazone group (Fig. 3). In the saline control subgroups, oleate clearance decreased somewhat after diet/exercise (0.88±0.20 l/min, Fig. 3), but increased after pioglitazone (1.09±0.13 l/min, Fig. 3). Similarly, in the insulin clamp groups, oleate clearance did not change significantly in response to diet/exercise (1.79±0.20 vs 1.92±0.30 l/min, pre- vs post-intervention, _p_=NS, Fig. 3), but, in contrast, increased from 1.80±0.21 to 2.52±0.24 l/min (p<0.01) in response to pioglitazone.

Plasma triglyceride radioactivity

The concentration of 3H-labelled triglyceride in plasma following intervention was virtually identical in the two groups (_p_=0.98 by ANOVA), averaging 964±92 and 994±264 dpm/ml in the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups during the saline condition, and 1,009±177 and 916±139 dpm/ml in the diet/exercise and pioglitazone groups during the insulin clamp, respectively.

Discussion

We assessed the effects of pioglitazone on overnight postabsorptive and insulin-regulated NEFA and glucose metabolism in non-diabetic men and women with upper body obesity. A diet/exercise group was also studied for comparison of the two insulin-sensitising regimens. To the extent that better regulation of NEFA concentrations has beneficial effects on the metabolic complications of upper body obesity, understanding whether and how these two regimens alter fatty acid metabolism may provide insights into mechanisms of health improvement.

After diet/exercise, the ability of insulin to suppress lipolysis was enhanced, resulting in ∼50% lower oleate concentrations during hyperinsulinaemia. In contrast, after pioglitazone treatment the ∼50% lower plasma oleate concentrations during the insulin clamp were due to a 40% increase in clearance rather than reduced lipolysis.

We have found no previous reports that pioglitazone increases NEFA clearance in humans, although increased NEFA clearance was seen during lipid emulsion infusion into thiazolidinedione-treated animals [35]. Previous studies suggested that thiazolidinediones lower NEFA concentrations in type 2 diabetes via improved insulin suppression of lipolysis [17–20]. In the current study of non-diabetic adults with upper body obesity we did not find greater insulin suppression of lipolysis. It is possible that the improved glycaemic control achieved with thiazolidinedione treatment of type 2 diabetes secondarily improves insulin suppression of lipolysis, whereas a primary effect of thiazolidinediones is enhanced removal of NEFA from the circulation. Another possible explanation for this discrepancy might be the use of glycerol kinetics rather than NEFA flux as a reflection of adipose tissue lipolysis in most of the studies [19]. Glycerol Ra is a reflection of both adipose tissue lipolysis and the intravascular hydrolysis of VLDL by lipoprotein lipase [36].

We found indirect evidence for enhanced insulin regulation of overnight postabsorptive lipolysis by both interventions; oleate release in the saline-infused volunteers was not increased in either the diet/exercise or pioglitazone groups, despite significantly reduced insulin concentrations. Lipolysis is exquisitely sensitive to insulin [37, 38], such that NEFA flux should have increased in our volunteers had there been no change in insulin's antilipolytic effects. The absence of this change implies that, at least at basal insulin concentrations, insulin was more effective at suppressing lipolysis.

Given the sensitivity of lipolysis to insulin regulation, one might question how our insulin clamp results relate to the daily fluctuations in NEFA availability. The plasma insulin concentrations we achieved during the insulin clamp are similar to those seen in upper body obese individuals following ingestion of a mixed meal [9]. In that same study [9] we found that the endogenous oleate concentrations observed at the postprandial nadir were similar to the suppressed steady-state levels we observed during this study. These insulin concentrations discriminate between upper body and lower body obesity in terms of suppression of lipolysis [9, 39], whereas lower doses of insulin do not [3]. In addition, the dose given in this study is identical to that we previously found to clearly discriminate between upper body obese and non-obese men and women in terms of glucose and NEFA metabolism (M. D. Jensen, unpublished results). Finally, the NEFA concentrations seen during hyperinsulinaemia following diet/exercise or pioglitazone are more in keeping with the lowest endogenous NEFA concentrations seen following meal ingestion in non-obese and lower body obese adults [9]. Because of the importance of insulin suppression of NEFA concentrations in regulating glucose metabolism [40], we believe that the dose of insulin we selected is relevant to the effects of diet/exercise and pioglitazone on postprandial metabolism.

These studies do not address the tissue(s) or the mechanism responsible for the greater NEFA clearance, although we can virtually exclude increased uptake into tissues that use NEFA for immediate oxidative needs. Increased NEFA uptake into muscle would have to be accompanied by increased fatty acid oxidation in order to prevent accumulation of intramyocellular fatty acids, which are thought to result in insulin resistance. Fatty acid oxidation was not increased following pioglitazone treatment in either the saline or the insulin clamp studies (Table 4); this would be expected if skeletal muscle were the primary site of increased NEFA clearance. Because fatty acid oxidation did not increase, this indicates that pioglitazone increased non-oxidative NEFA clearance. One tissue that might account for this is the liver, which could then export the NEFAs as VLDL triglyceride back to adipose tissue. Adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase (LPL) can act on VLDL triglyceride [41] such that circulating VLDL triglyceride [42] can return to adipose tissue via a form of ‘tissue substrate cycling’. A recent report showed that pioglitazone treatment of type 2 diabetes lowered VLDL triglyceride concentrations, did not increase hepatic VLDL triglyceride production, but did increase VLDL triglyceride clearance [43]. Whether the same effects occur in non-diabetic individuals is unknown. Serum triglyceride concentrations did not decrease in our group. Thus, if VLDL triglyceride clearance increased in this study, VLDL triglyceride production must have also increased. Another possible route of NEFA clearance might be direct uptake into adipose tissue, although the lack of NEFA tracer uptake across adipose tissue [44] argues against this possibility. Either of these processes could allow increased non-oxidative NEFA clearance without predisposing to ectopic fat deposition.

Both diet/exercise and pioglitazone interventions improved peripheral insulin action as assessed by fasting glucose insulin and C-peptide concentrations, insulin sensitivity from an intravenous glucose tolerance test [24], and glucose Rd during a euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp. Surprisingly, endogenous glucose production was greater during the insulin clamp after pioglitazone treatment, albeit this was in the context of 25% lower plasma insulin concentrations. This response of endogenous glucose production to thiazolidinediones has previously been reported to occur in dogs [45] and humans [34], despite increased peripheral insulin sensitivity. It was speculated [34] that this phenomenon is caused by a thiazolidinedione-induced increase in insulin clearance (which is consistent with our data), since endogenous glucose Ra is quite sensitive to small changes in plasma insulin concentrations. It should be noted that some investigators have found greater suppression of endogenous glucose production following pioglitazone treatment of type 2 diabetes during a 40 mU/min−1 m−2 dose insulin clamp [16]. Whether our results disagree with these because of population differences (non-diabetic subjects) or differences in insulin infusion rates is unclear.

The 6-h [3H]oleate infusion used in our study resulted in incorporation of the NEFA tracer into circulating triglycerides. The VLDL triglycerides are thought to be taken-up in peripheral tissues via LPL-mediated hydrolysis [41]. If some of the fatty acids from circulating triglycerides escape uptake by tissues following hydrolysis and enter the circulating NEFA pool, this would create a second source of [3H]oleate (in addition to the tracer being infused). Because the NEFA turnover calculation assumes a single, externally infused source of 3H-oleate, an ‘escape’ of [3H]oleate from VLDL triglyceride could cause an underestimation of oleate flux. This would be a special problem for interpreting our clearance data from the post-intervention study if there were different amounts of radiolabelled triglycerides in plasma between the groups. The finding that plasma [3H]triglyceride concentrations were virtually identical between groups implies that, if this process occurs, its effect would be equal in each group. Thus, our conclusion that NEFA clearance increases with pioglitazone is not confounded by differences in plasma [3H]triglyceride concentrations.

In summary, in this study we examined the effects of pioglitazone vs diet/exercise treatment on the insulin regulation of NEFA and glucose metabolism in non-diabetic adults with upper body obesity. Both interventions improved insulin sensitivity with respect to glucose metabolism, although diet/exercise resulting in an average 9-kg fat loss appears to be somewhat better than pioglitazone. Pioglitazone increased NEFA clearance most dramatically during physiological hyperinsulinaemia, resulting in reduced NEFA concentrations without reduced lipolysis. The greater NEFA clearance is unlikely to be the result of insulin sensitisation per se, since it was not seen in the diet/exercise group. This action of thiazolidinediones may be important in their ability to improve glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes.

References

- Evans DJ, Hoffmann RG, Kalkhoff RK, Kissebah AH (1984) Relationship of body fat topography to insulin sensitivity and metabolic profiles in premenopausal women. Metabolism 33:68–75

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Peiris AN, Struve MF, Mueller RA, Lee MB, Kissebah AH (1988) Glucose metabolism in obesity: influence of body fat distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67:760–767

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Jensen MD, Haymond MW, Rizza RA, Cryer PE, Miles JM (1989) Influence of body fat distribution on free fatty acid metabolism in obesity. J Clin Invest 83:1168–1173

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Groop LC, Bonadonna RC, DelPrato S, Ratheiser K, Zyck K, Ferrannini E et al (1989) Glucose and free fatty acid metabolism in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 84:205–213

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Basu A, Basu R, Shah P, Vella A, Rizza RA, Jensen MD (2001) Systemic and regional free fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280:E1000–E1006

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Miles JM, Ellman MG, McClean KL, Jensen MD (1987) Validation of a new method for determination of free fatty acid turnover. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 252:E431–E438

CAS Google Scholar - Nielsen S, Guo Z, Albu JB, Klein S, O'Brien PC, Jensen MD (2003) Energy expenditure, sex, and endogenous fuel availability in humans. J Clin Invest 111:981–988

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Havel RJ, Carlson LA, Ekelund L, Holmgren A (1964) Turnover rate and oxidation of different free fatty acids in man during exercise. J Appl Physiol 19:613–618

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Roust LR, Jensen MD (1993) Postprandial free fatty acid kinetics are abnormal in upper body obesity. Diabetes 42:1567–1573

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kelley DE, Mokan M, Simoneau JA, Mandarino LJ (1993) Interaction between glucose and free fatty acid metabolism in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest 92:91–98

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Boden G, Chen X, Ruiz J, White JV, Rossetti L (1994) Mechanisms of fatty acid-induced inhibition of glucose uptake. J Clin Invest 93:2438–2446

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rebrin K, Steil GM, Mittelman SD, Bergman RN (1996) Casual linkage between insulin suppression of lipolysis and suppression of liver glucose output in dogs. J Clin Invest 98:741–749

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Lewis GF, Uffelman KD, Szeto LW, Weller B, Steiner G (1995) Interaction between free fatty acids and insulin in the acute control of very low density lipoprotein production in humans. J Clin Invest 95:158–166

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Steinberg HO, Tarshoby M, Monestel R et al (1997) Elevated circulating free fatty acid levels impair endothelium-dependent vasodilation. J Clin Invest 100:1230–1239

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kanaley JA, Andresen-Reid ML, Oenning L, Kottke BA, Jensen MD (1993) Differential health benefits of weight loss in upper-body and lower-body obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 57:20–26

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Miyazaki Y, Mahankali A, Matsuda M, Mahankali S, Hardies J, Cusi K et al (2002) Effect of pioglitazone on abdominal fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2784–2791

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Miles JM, Wooldridge D, Grellner WJ et al (2003) Nocturnal and postprandial free fatty acid kinetics in normal and type 2 diabetic subjects: effects of insulin sensitization therapy. Diabetes 52:675–681

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Boden G, Cheung P, Mozzoli M, Fried SK (2003) Effect of thiazolidinediones on glucose and fatty acid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 52:753–759

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Mayerson AB, Hundal RS, Dufour S et al (2002) The effects of rosiglitazone on insulin sensitivity, lipolysis, and hepatic and skeletal muscle triglyceride contents in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 51:797–802

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Racette SB, Davis AO, McGill JB, Klein S (2002) Thiazolidinediones enhance insulin-mediated suppression of fatty acid flux in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 51:169–174

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Firth RG, Bell PM, Rizza RA (1986) Effects of tolazamide and exogenous insulin on insulin action in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 314:1280–1286

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Botion LM, Green A (1999) Long-term regulation of lipolysis and hormone-sensitive lipase by insulin and glucose. Diabetes 48:1691–1697

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Smith U (1974) Studies of human adipose tissue in culture: III. Influence of insulin and medium glucose concentration on cellular metabolism. J Clin Invest 53:91–98

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Shadid S, Jensen MD (2003) Effects of pioglitazone vs diet and exercise on metabolic health and fat distribution in upper body obesity. Diabetes Care 26:3148–3152

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Shadid S, Jensen MD (2002) Angioneurotic edema as a side effect of pioglitazone. Diabetes Care 25:405

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Brownell KD (2002) The LEARN program for weight management 2000. American Health Publishing Company, Dallas

Google Scholar - Kury D, Keller U (1991) Trimethylsilyl-_O_-methyloxime derivatives for the measurement of [6,6-2H2]-d-glucose-enriched plasma samples by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr 572:302–306

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Causon RC, Carruthers ME, Rodnight R (1981) Assay of plasma catecholamines by liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal Biochem 116:223–226

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Humphreys SM, Fisher RM, Frayn KN (1990) Micromethod for measurement of sub-nanomole amounts of triacylglycerol. Ann Clin Biochem 27:597–598

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226:497–509

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Jensen MD (1995) Gender differences in regional fatty acid metabolism before and after meal ingestion. J Clin Invest 96:2297–2303

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Tanner JM (1949) Fallacy of per-weight and per-surface area standards, and their relation to spurious correlation. J Appl Physiol 2:1–15

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Coon PJ, Rogus EM, Drinkwater DT, Muller DC, Goldberg AP (1992) Role of body fat distribution in the decline in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance with age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75:1125–1132

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Tiikkainen M, Häkkinen A-M, Korsheninnikova E, Nyman T, Mäkimattila S, Yki-Jarvinen H (2004) Effects of rosiglitazone and metformin on liver fat content, hepatic insulin resistance, insulin clearance, and gene expression in adipose tissue in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53:2169–2176

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hevener AL, Reichart D, Janez A, Olefsky J (2001) Thiazolidinedione treatment prevents free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in male Wistar rats. Diabetes 50:2316–2322

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Jensen MD, Chandramouli V, Schumann WE et al (2001) Sources of blood glycerol during fasting. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281:E998–E1004

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Jensen MD, Caruso M, Heiling V, Miles JM (1989) Insulin regulation of lipolysis in nondiabetic and IDDM subjects. Diabetes 38:1595–1601

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Jensen MD (1991) Regulation of forearm lipolysis in different types of obesity. In vivo evidence for adipocyte heterogeneity. J Clin Invest 87:187–193

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Guo ZK, Hensrud DD, Johnson CM, Jensen MD (1999) Regional postprandial fatty acid metabolism in different obesity phenotypes. Diabetes 48:1586–1592

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rebrin K, Steil GM, Getty L, Bergman RN (1995) Free fatty acids as a link in the regulation of hepatic glucose output by peripheral insulin. Diabetes 44:1038–1045

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Coppack SW, Evans RD, Fisher RM et al (1992) Adipose tissue metabolism in obesity: lipase action in vivo before and after a mixed meal. Metabolism 41:264–272

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Havel RJ, Kane JP, Balasse EO, Segel N, Basso LV (1970) Splanchnic metabolism of free fatty acids and production of triglycerides of very low density lipoproteins in normotriglyceridemic and hypertriglyceridemic humans. J Clin Invest 49:2017–2035

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Nagashima K, Lopez C, Donovan D et al (2005) Effects of the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone on lipoprotein metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 115:1323–1332

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Coppack SW, Persson M, Judd RL, Miles JM (1999) Glycerol and nonesterified fatty acid metabolism in human muscle and adipose tissue in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 276:E233–E240

CAS Google Scholar - Dea MK, Van Citters GW, Ader M, Mittelman SD, Sunehag AL, Bergman RN (2000) Paradoxical effect of troglitazone in normal animals: enhancement of adipocyte by reduction of liver insulin sensitivity. Diabetes 49:2087–2093

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar