The endocannabinoid system in obesity and type 2 diabetes (original) (raw)

Introduction

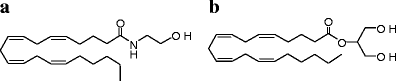

The endocannabinoid (EC) system was identified in the early 1990s during investigations into the mechanism of action of the major cannabis-derived psychotropic compound, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) [1, 2]. The cloning of cannabinoid receptors led to the identification of endogenous molecules capable of binding and activating them, defined as ‘endocannabinoids’ because despite being chemically different from THC they are still capable of recognising its specific binding sites [3]. The two most widely studied ECs, anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (Fig. 1), are phospholipid-derived lipids containing an arachidonic acid chain in their chemical structure. Anabolic and catabolic enzymes for ECs are still being identified and cloned [4–6]. These proteins, together with the ECs and the type 1 and 2 cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2), constitute the EC system. Since anandamide, but not 2-AG, is also an agonist of transient receptor vanilloid type-1 (TRPV1) [7], some authors consider this unselective cation channel to be part of the EC system.

Fig. 1

Chemical structures of the two most widely studied endocannabinoids, anandamide (a) and 2-AG (b)

Anandamide and that part of 2-AG that acts as an endocannabinoid (2-AG is also an intermediate in triacylglycerol and phospholipid metabolism) are released from cells immediately after their production (i.e. with no intermediate storage in vesicles) to activate their targets locally. ECs are produced following an elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels, and are inactivated when paracrine or autocrine cannabinoid receptor activation is to be terminated [8, 9].The general strategy of EC function is to restore local homeostasis when it becomes disrupted under stressful conditions. Excessive neuronal activity, cell damage and exaggerated stimulation of inflammatory cytokine receptors are examples of pathological conditions leading to EC biosynthesis that are dampened by cannabinoid receptor activation. In addition, there are physiological perturbations of homeostasis that can trigger EC production, which, together with other homeostatic signalling systems, helps cells return to their steady state. During conditions of prolonged or chronic perturbations, however, the EC system often becomes dysregulated, i.e. the production and action of ECs lose specificity in time and space. Thus, cannabinoid receptors become ‘overactive’ or are activated on cells that were not originally meant to be targeted by ECs [10].

In mammals, emotional stress is one condition leading to changes in the EC system. Various types of acute or chronic stressors will trigger EC production and CB1 receptor activation in a site-and time-specific manner in the brain, this being one of the mechanisms that helps the organism to cope with, and recover from, the consequences of stress [11–15]. Accordingly, cross-talk between glucocorticoids and the EC system has been described [16, 17]. Brief food deprivation constitutes an acute perturbation of homeostasis, and it is therefore not surprising to discover that it is accompanied by transient elevation of EC levels in the hypothalamus and limbic forebrain, with subsequent activation of CB1 receptors, which stimulates food intake [18, 19]. Recent evidence indicates that the EC system is not only needed to help animals re-establish their energy status via central stimulation of appetite and motivation to consume food [20]. As described in the following sections, it also participates in the storage of newly acquired energy into fat. In fact, CB1 null mice not only consume less food after food deprivation [18], but also accumulate less fat in adipose tissue as compared with pair-fed wild-type mice [21].

Role of the EC system in adipogenesis and lipogenesis

Effects of CB1 stimulation on adipocyte differentiation and proliferation

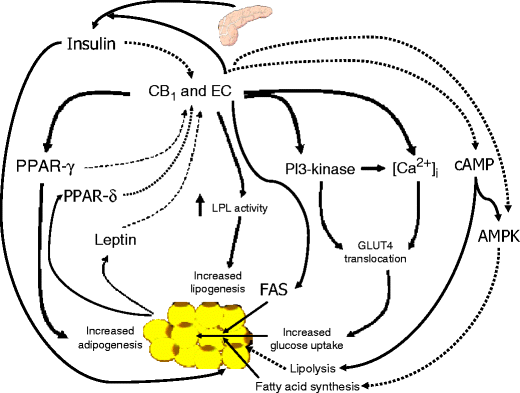

Increasing evidence indicates that the EC system plays an important role in adipogenesis (Fig. 2). EC and CB1 levels increase following mouse 3T3 and human pre-adipocyte differentiation into mature adipocytes [22–26]. CB1 stimulation of both mouse 3T3 and human pre-adipocytes is accompanied by upregulation of mRNA for one of the key players in the activation of this process, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) [23, 26], and by increased adipocyte size and triacylglycerol content [23]. There is also indirect evidence of a role for CB1 in the determination of adipocyte number in adipose tissue, since blockade of this receptor inhibits mouse 3T3 adipocyte proliferation [27]. Thus, perhaps following central CB1-mediated energy intake, adipocyte CB1 stimulation ensures that enough fat storage cells are present in the adipose tissue and that they accommodate as much fat as possible.

Fig. 2

Role of the endocannabinoid system in adipogenesis and lipogenesis, and its regulation. Solid lines denote activation, broken lines denote inhibition. Note the several ways through which CB1 stimulation can increase the storing capacity of adipose tissue by stimulating preadipocyte differentiation (via upregulation of adipocyte PPAR-γ levels and, possibly, by stimulating insulin release from beta cells), and enhancing de novo fatty acid synthesis (via stimulation of LPL and upregulation of FAS levels and glucose uptake), reducing fatty acid oxidation (via inhibition of AMPK), and enhancing triacylglycerol accumulation (via inhibition of lipolysis). Also note how the system is negatively regulated by PPARs, leptin [23, 26] and insulin [48]. LPL, lipoprotein lipase; PI3-kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Based on data from [23, 26, 48]

Effects of CB1 stimulation on adipocyte lipogenesis

In addition to PPAR-γ EC-mediated fat accumulation in adipocytes involves a large variety of molecular mechanisms (Fig. 2), including (1) activation of lipoprotein lipase [21], to provide the adipocyte with exogenous fatty acids for triacylglycerol synthesis; (2) inhibition of adenylate cyclase [23], to inhibit lipolysis and stimulate triacylglycerol synthesis; (3) inhibition of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [28], with subsequent inhibition of fatty acid oxidation; (4) enhancement of both basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake [24, 26] and stimulation of fatty acid synthase (FAS) production [29], to provide adipocytes with glucose for the production of precursors for FAS-catalysed de novo fatty acid synthesis and of glycerol for triacylglycerol biosynthesis. The role of CB1 in the tonic inhibition of lipolysis is also suggested by in vivo experiments showing that acute blockade of this receptor causes lipolysis in fat tissue, as evidenced by increased plasma NEFA [30, 31].

To avoid excessive lipid accumulation in adipocytes, these mechanisms are normally subject to autocrine regulation in mature adipocytes, which limits both EC and CB1 levels through various mediators, including (1) leptin, which reduces EC levels in these cells [23], as also observed in the hypothalamus [18]; (2) PPAR-γ, which has a negative feedback effect on both CB1 content [26] and EC levels [23], perhaps by upregulating one of the enzymes responsible for their degradation, the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) [26]; and (3) PPAR-δ, which negatively regulates CB1 content [32]. Exogenous insulin might also limit EC levels, since hyperinsulinaemia in lean humans correlates with the upregulation of Faah mRNA levels in the subcutaneous adipose tissue [33], whereas postprandial and postoral glucose hyperinsulinaemia is accompanied by decreased plasma EC levels [23], two effects that are not observed in obese individuals (see below).

The other proposed major molecular target for anandamide, the TRPV1 channel, has been shown to be produced in pre-adipocytes and to inhibit adipogenesis [34]. Therefore, 2-AG, which does not activate TRPV1 receptors, and anandamide might play different roles in adipogenesis, particularly since, under certain conditions, TRPV1 stimulation inhibits 2-AG biosynthesis [35]. This might explain why the two major ECs are often differentially regulated during adipogenesis and following hyperinsulinaemia and obesity [23, 36, 37]. Less clear is the role, in adipocytes, of CB2 which is activated more efficaciously by 2-AG than by anandamide. Data on the presence of CB2 in these cells are inconsistent [23–26, 38] and, clearly, further studies are needed in this area.

Effects of CB1 stimulation on fatty acid synthesis and oxidation in non-adipose organs

Some of the pro-lipogenetic effects of CB1 stimulation described above have also been reported to occur in other organs. Inhibition of adenylate cyclase is an intracellular signalling event coupled to CB1 in several tissues [2]. AMPK inhibition by THC and/or 2-AG occurs in the liver [28]. CB1 blockade is coupled to stimulation of AMPK in cultured human skeletal muscle myotubes, thus indirectly suggesting a tonic inhibition of AMPK by ECs in skeletal muscle [39]. CB1 coupling to elevation of FAS and acetyl-CoA carboxylase levels has been reported in liver [29]. These findings appear to indicate that the EC system might induce lipogenesis and inhibit lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation in non-adipose organs. This would imply that, under pathological conditions where this system becomes overactive (see below), the EC system might actively and directly participate in ectopic fat formation in various organs, and hence in reduced insulin sensitivity and increased cardiovascular risk [40]. Obviously, the role of CB1 in reducing fatty acid oxidation in non-adipose tissues, also suggested by in vivo studies with CB1 blockers [30, 31], needs to be further investigated.

Role of the EC system in glucose metabolism

The potential role of the EC system in glycaemic control was suggested by indirect in vivo experiments carried out in rats. First, acute intraperitoneal administration of CB1 agonists retards the clearance of plasma glucose after the oral administration of glucose. Interestingly, CB2 agonists exert the opposite effect. The effects of CB1 and CB2 agonists are prevented by inactive doses of the respective antagonists, which, at higher doses, accelerate or retard the clearance of plasma glucose, respectively [41]. Furthermore, oral administration of a single dose of the CB1 antagonist AVE1625 to rats causes liver glycogenolysis and an immediate increase in total energy expenditure, as measured by indirect calorimetry, which was attributed not only to a long-lasting increase in fat oxidation, but also to a transient increase in glucose oxidation [30]. These findings indicate that, in glucose-utilising tissues of lean rats, there might be endogenous levels of ECs high enough for tonic activation of CB1 but not CB2. This would, in turn, decrease glucose utilisation, which would possibly be advantageous for EC-mediated glucose uptake by adipocytes for de novo triacylglycerol biosynthesis. These putative effects of ECs might be due to reduction of insulin release from beta cells or inhibition of insulin sensitivity at the level of non-adipose glucose-utilising tissues, or both.

Potential role of ECs in the endocrine pancreas

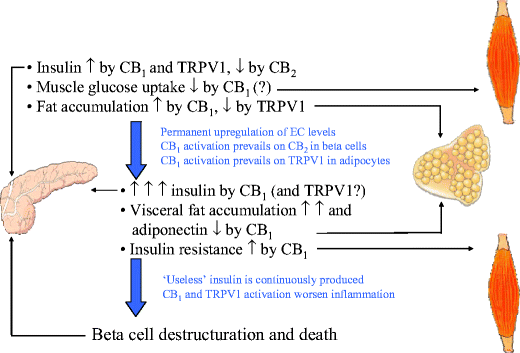

This section provides a summary of the results of recent studies on the expression of cannabinoid receptors in the endocrine pancreas. First, in mice, CB1 seems to be mostly expressed in alpha cells, based on immunohistochemical co-localisation with glucagon, whereas CB2 is abundant in beta cells, based on co-localisation with insulin [42, 43]. In one recent report [44], however, the inhibitory action of CB1 agonists on insulin secretion prompted the authors to suggest the presence of CB1 in mouse beta cells. In this study, however, no immunohistochemical co-localisation with insulin or glucagon was performed, and the effect of CB1 antagonists on the agonists used was not studied. Interestingly, alpha, but not beta, cells from lean mice also contain EC synthesising enzymes, whereas beta, but not alpha, cells produce EC degrading enzymes, suggesting a paracrine action of ECs in mouse pancreatic islets [43]. Second, in the rat and human pancreas, CB1 is instead co-expressed with both insulin and glucagon, suggesting that this receptor is present in beta cells, which also express CB2 [42, 43]. Contrary to findings in the mouse [44], rat insulinoma and human beta cells respond to CB1 stimulation by increasing insulin secretion [23, 45]. Interestingly, CB1 agonists also enhance glucagon release from human alpha cells, whereas CB2 agonists reduce both insulin and glucagon release. Thus, the modulatory effects of CB1 and CB2 activation on insulin release observed in rat and/or human pancreatic islets do not account for the inhibition or stimulation of plasma glucose clearance, respectively, caused by these two stimuli in rats after oral glucose administration [41]. This might suggest that the effects of ECs on plasma glucose levels in lean rats are not due to altered insulin release from beta cells but rather to actions on insulin sensitivity (e.g. in skeletal muscle) or modulation of hepatic glucose release/uptake (see below). Therefore, if the in vitro data on the effects of cannabinoid receptor agonists on insulin release can be extrapolated to the in vivo situation, it seems unlikely that the endocrine pancreas plays an important role in CB1-mediated glucose intolerance (although it might influence the putative contribution of CB1 to type 2 diabetes, see below and Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Hypothetical role of the endocannabinoid system in type 2 diabetes. After a meal in a normal weight/normoglycaemic individual, endocannabinoid-induced CB1 and TRPV1 stimulatory actions on insulin release [44, 81] might be counteracted by CB2 [45], possibly as a result of the preponderance of 2-AG (most active on both CB1 and CB2 receptors) over anandamide (most active on CB1 and TRPV1 receptors) levels. In hyperglycaemia and obesity, both anandamide and 2-AG levels are permanently increased in the pancreas (see Fig. 2), thus causing overstimulation of CB1 and TRPV1 vs CB2 receptors, and enhanced insulin release [45, 81]. At the same time, insulin sensitivity is decreased by elevated 2-AG levels in the skeletal muscle, whereas elevation of adipocyte 2-AG, but not anandamide, levels causes preferential activation of pro-lipogenetic CB1 vs anti-lipogenetic [34] TRPV1 receptors, visceral fat accumulation and reduced adiponectin production. These events together cause more insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, thus leading to beta cell hypertrophy, destructuration and damage, ultimately contributing to type 2 diabetes, possibly also through CB1 and TRPV1-mediated proinflammatory actions

Potential role of ECs in skeletal muscle glucose metabolism

Although evidence points to a desensitising effect of CB1 stimulation on insulin-induced glucose uptake and oxidation in skeletal muscle, no studies to date have investigated this possibility. CB1 receptors are found in both mouse and human skeletal muscle [46, 47], but it is unknown if they modify the intracellular signalling events down-stream of insulin receptor stimulation. Cavuoto and colleagues [39] showed an increase in PRKAA1 (also known as AMPKA1) mRNA content following human myotube treatment with the CB1 antagonist AM251, which was reverted by co-incubation with anandamide. Although the relationship between this event and insulin sensitivity was not investigated, one might hypothesise that ECs inhibit the production of AMPKα1 in skeletal muscle and, hence, glucose (and fatty acid) oxidation. However, cannabinoid receptor agonists did not modify AMPK activity in rat skeletal muscle [28]. Interestingly, not only CB1, but also CB2 and TRPV1 are present in human and rodent skeletal muscle [47]. Therefore, much work will be needed to understand the role of ECs in the control of glucose utilisation by skeletal muscle.

Potential role of ECs in hepatic glucose metabolism

Not much is known about the role of CB1 in hepatic control of glucose metabolism. It must be emphasised that the amount of CB1 in the liver is very low (although there is a clear upregulation of CB1 production in the liver of mice with diet-induced obesity, see below). Nevertheless, as mentioned above, evidence suggests that acute systemic blockade of CB1 in lean rats increases liver glycogenolysis [30]. This, however, does not necessarily mean that activation of CB1 produces the opposite effect, nor that it does so by directly targeting the liver. Importantly, cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit AMPK in the liver [28] and, although the role of CB1 receptors in this effect has not been shown yet, this might enhance hepatic gluconeogenesis. Whilst it is conceivable that changes in glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis are reflected by changes in glucose release from the liver, studies on the direct effect of CB1 agonists or antagonists on hepatic glucose production have not been conducted as yet, and this represents an area for future investigation. The same reasoning applies to studies on insulin sensitivity performed with euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamps (in both animals and humans), which are necessary to confirm the role of cannabinoid receptors in insulin sensitivity.

Dysregulation of the EC system in obesity, hyperglycaemia and diabetes

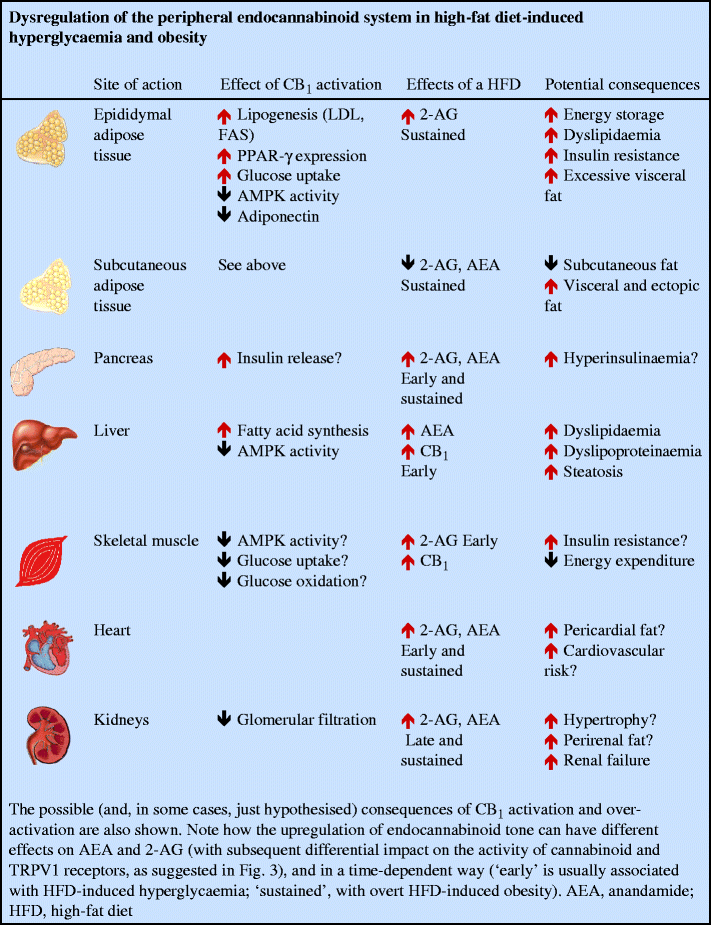

Evidence from animal models

The possibility that the EC system becomes dysregulated during obesity and diabetes was proposed following the realisation that EC and/or CB1 levels in both nervous and non-nervous tissues involved in energy homeostasis are under the control of hormones, the levels of which are altered during these metabolic disorders. In obese rodents with a malfunctioning leptin signalling system, it was not surprising to observe permanently elevated EC levels in the tissue with the highest levels of leptin receptor expression, the hypothalamus, where leptin downregulates EC biosynthesis [18]. In peripheral organs, if it is confirmed that insulin downregulates EC levels or upregulates EC degradation in lean animals, as shown in rat insulinoma cells [23], mouse 3T3L1 adipocytes [48] and human subcutaneous fat cells [33], elevated EC levels might be caused by insulin resistance. Elevation of 2-AG and/or anandamide levels precedes the development of overt obesity and accompanies hyperglycaemia in the liver [29], pancreas [43], brown adipose tissue, soleus muscle and heart [49] of mice fed high-fat diets, whereas increases in renal EC levels was only seen in overtly obese mice [49] (see text box: Dysregulation of the peripheral endocannabinoid system in high-fat diet-induced hyperglycaemia and obesity). In the mouse pancreas, early (3 and 8 weeks), but not late (14 weeks), elevations in both anandamide and 2-AG levels following a high-fat diet were accompanied by the presence of biosynthetic enzymes in alpha cells and beta cells, and downregulation of FAAH in alpha cells [43]. Downregulation of FAAH levels and upregulation of CB1 levels also accompanied elevation of hepatic EC levels in mice fed for 3 weeks with a different high-fat diet [29]. Interestingly, again in mice after high-fat diets, there was a striking redistribution of EC tone in the various fat depots, with decreased, unchanged and increased levels observed in the subcutaneous, mesenteric and epididymal fat, respectively [23, 43, 48]. In two endocrine organs involved in the control of energy homeostasis, the adrenal gland and the thyroid, the observed changes in 2-AG levels are dependent not only on the duration, but also on the fatty acid composition of the high-fat diet [49]. In isolated adipocytes, the type of fatty acids delivered to the cell influence EC levels, with _n_-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids producing a decrease and arachidonic acid producing an increase [50].

Discrepant results exist regarding the upregulation of CB1 receptors in obese rodents. Increased amounts of Cnr1 expression and levels of CB1, the encoded protein, were found in the visceral and subcutaneous (but not brown) fat of rats after a high-fat diet, and this phenomenon seems to be related to a concomitant reduction in PPAR-δ levels. In fact, in these obese rats, exercise elevated PPAR-δ production and decreased CB1 levels [32]. Conversely, CB1 (and CB2) levels did not change in either the subcutaneous or mesenteric fat of mice that became obese following a high-fat diet [43].

Evidence in humans

The first evidence of peripheral elevation of EC tone in humans came from studies in overweight/obese women with a binge eating disorder [51] and in obese postmenopausal women [52], in whom elevated blood levels of anandamide only, or both anandamide and 2-AG, respectively, were reported. However, elevation of only 2-AG levels was observed in the visceral, but not subcutaneous, adipose tissue of overweight/obese humans [23]. The overactivity of the EC system in the visceral vs subcutaneous adipose depots was confirmed by studies showing a positive correlation between plasma levels of 2-AG, but not anandamide, and the amount of intra-abdominal fat (measured by computed tomography) [36, 37]. In non-obese patients (BMI ~30) with type 2 diabetes with only partially controlled hyperglycaemia, plasma levels of anandamide and 2-AG are elevated compared with those in non-diabetic matched controls [23]. Importantly, although ECs are not circulating hormones, there is evidence suggesting that plasma levels of 2-AG (which are at least two orders of magnitude lower than those measured in tissues) are partly the result of peripheral organ spill-over (V. Di Marzo, unpublished data).

One possible cause of elevated peripheral EC levels is the downregulation of EC degrading enzyme levels, which has been observed in the visceral and subcutaneous fat of obese patients [36, 52, 53]. Lack of FAAH mRNA upregulation by insulin has been reported in the subcutaneous fat of obese vs lean patients [33]. Accordingly, Sipe et al. [54] found a correlation between overweight/obesity and a missense polymorphism in the Faah gene, although this finding was not confirmed by other authors [55]. Others have, instead, reported an increase in mRNAs for degrading enzymes in visceral fat compared with a decrease in gluteal subcutaneous fat [26]. However, these changes were accompanied by parallel changes in levels of mRNAs for EC biosynthetic enzymes, in agreement with elevated EC levels in the visceral vs subcutaneous fat of obese patients [26].

Results regarding CB1 expression in human obesity are also controversial. Downregulation has been observed in the omental and subcutaneous adipose depots by some authors [36, 52, 56], but not others [23]. Löfgren et al. found no changes in CNR1 mRNA levels in either depot of obese patients, and no correlation with adiponectin mRNA content [53]. It has also been reported that CNR1 mRNA levels are increased in the visceral fat and subcutaneous abdominal fat, and decreased in the gluteal subcutaneous fat [26]. From these data it appears that the measurement of EC metabolic enzyme and CNR1 mRNA levels is particularly sensitive to differences in experimental procedures and patient cohorts, and will require further investigation. Correlations between polymorphisms in CNR1, the gene encoding CB1, and the occurrence of lean or obese phenotypes in various adult human populations have also been found [57–60]. Clearly, any conclusion as to the pathological relevance of these findings must await further studies assessing the impact of these mutations on the functional activity of CB1 and identifying those sequences in CNR1 that are relevant to the development of obesity. The latter of these issues was partly addressed in a recent study carried out in 1,932 obese cases and 1173 non-obese controls of French-European origin [[61](/article/10.1007/s00125-008-1048-2#ref-CR61 "Benzinou M, Chèvre J-C, Ward KJ et al (2008) Endocannabinoid receptor 1 gene variations increase risk for obesity and modulate body mass index in European populations. Hum Mol (in press) Genet DOI 10.1093/hmg/ddn089

")\]. Of 25 successfully genotyped _CNR1_ single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), 12 showed nominal evidence of association with childhood obesity, class I and II and/or class III adult obesity. Intronic SNPs rs806381 and rs2023239 were also associated with higher BMI in both Swiss obese individuals and Danish individuals. The genotyping of all known variants in partial linkage disequilibrium with these two SNPs in an initial case–control study identified two SNPs (rs6454674 and rs10485170) more strongly associated with BMI \[[61](/article/10.1007/s00125-008-1048-2#ref-CR61 "Benzinou M, Chèvre J-C, Ward KJ et al (2008) Endocannabinoid receptor 1 gene variations increase risk for obesity and modulate body mass index in European populations. Hum Mol (in press) Genet DOI

10.1093/hmg/ddn089

")\].Consequences of a dysregulated EC system

The dysregulation of EC and CB1 levels might affect all those biological actions that are exerted through the EC system in various organs. In adipose tissues, the imbalance between EC tone in the visceral and subcutaneous depots might determine an excessive accumulation of fat in the former at the expense of the latter. Given the proposed role of intra-abdominal fat in insulin resistance and atherogenic inflammation [40], this might contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis. This scenario would be exacerbated if, as shown to date in mouse and rat [23, 62], but not human [26, 52] mature/hypertrophic adipocytes, CB1 stimulation inhibits the production and release of adiponectin, an important insulin-sensitising and anti-inflammatory adipokine. Indeed, obesity-related EC system overactivation in human obese patients is accompanied by increased production of visceral adipose tissue TNF-α which, in turn, stimulates EC system activation in vitro [56], thereby generating a potential vicious circle for atherogenic inflammation. In the liver, increased levels of both CB1 and EC might facilitate not only non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [29] and its cardiovascular consequences [40], but also excessive hepatic fatty acid and triacylglycerol production, which contribute to insulin resistance and low HDL-/high VLDL-cholesterol, respectively. In skeletal muscle and the pancreas, the consequences of what, in rodents, seems to be an early overactive EC system [43, 49] have yet to be determined, but might include reduced insulin sensitivity and excessive insulin release, respectively, which might lead to further hyperglycaemia and, eventually, to pancreatic beta cell hypertrophy and death (Fig. 3).

The potential cause–effect relationship between EC overactivity, particularly in the intra-abdominal fat depot, and human cardiometabolic risk factors is suggested by the finding that high plasma 2-AG levels are correlated with increased triacylglycerol and fasting glucose and reduced insulin sensitivity and HDL-cholesterol in obese patients [36, 37].

CB1 receptor blockers against obesity and type 2 diabetes

The most convincing evidence that the dysregulated EC system plays a major role in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes, and their cardiovascular and renal consequences, and in hepatosteatosis, comes from studies carried out in animal models of these two metabolic disorders involving congenital or prolonged pharmacological blockade of CB1 receptors, as well as from the five published clinical studies on the chronic administration of CB1 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists. These studies were recently reviewed (for examples, see [63–65]) and will only be briefly discussed here.

Studies in obese animals

In genetically or high-fat diet-fed obese rodents, Cnr1 knockout or prolonged treatment with CB1 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists causes a transient inhibition of food intake and a sustained reduction in body weight [66]. These effects are accompanied by reductions in hyperglycaemia and hypertriacylglycerolaemia, and an increase in the HDL-:LDL-cholesterol ratio [67]. Interference with CB1 function in mice also prevents the development of HFD-induced obesity and hepatosteatosis [29]. In obese Zucker rats with or without diabetes, chronic treatment with the CB1 antagonist rimonabant also reduces renal failure and beta cell disruption [68] or hepatosteatosis [69], respectively, in a manner largely independent from food intake. An emerging observation that deserves a special mention is that increased energy expenditure is a major contributor to that part of the weight loss-inducing effect of rimonabant in obese rodents that is independent from its anorectic action. A study on female candy-fed Wistar rats treated daily with rimonabant (10 mg/kg) and matched pair-fed rats was recently conducted to distinguish between a merely hypophagic action and an effect on energy expenditure [31]. Body weight was reduced by CB1 antagonism to levels nearly as low as those seen in rats fed standard rat chow. Evaluation of the balance between energy expenditure (measured by indirect calorimetry) and metabolisable energy intake (calculated by bomb calorimetry) revealed that, as a result of increased fat oxidation, the former made a greater contribution to sustained body weight reduction than reduced food intake. Pair-feeding did not result in comparable effects because animals reduced their energy expenditure to save energy stores. Rimonabant also elevated NEFA levels postprandially, demonstrating its inherent ability to induce lipolysis in a manner not secondary to post-absorptive reductions in food intake. The authors concluded that, in these obese rats, ‘the weight reducing effect of rimonabant was due to continuously elevated energy expenditure based on increased fat oxidation driven by lipolysis from fat tissue as long as fat stores were elevated’ [31]. However, in a previous study carried out in ob/ob mice, rimonabant was also shown to increase glucose uptake and oxygen consumption in the soleus muscle, thus suggesting that increased skeletal muscle glucose oxidation (possibly as a result of increased insulin sensitivity in this tissue) might also play a role in the enhanced energy expenditure observed in response to CB1 antagonism [70].

Clinical studies

The Rimonabant in Obesity (RIO) programme evaluated the efficacy and safety of rimonabant in four Phase III randomised trials in which more than 6,000 overweight or obese subjects received double-blind treatment with rimonabant (5 or 20 mg/day) or placebo plus diet and/or lifestyle modification therapy for 1 or 2 years [71–74]. These trials consistently found that 1 year of treatment with rimonabant 20 mg significantly increased weight loss and reduced waist circumference compared with diet or lifestyle therapy alone (Table 1). A double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-week study of another CB1 receptor inverse agonist, taranabant, in 358 obese/overweight adult completers, reported that weight loss was increased and waist circumference reduced at all evaluated doses (0.5, 2, 4 and 6 mg/day) compared with placebo [75]. Very importantly, in a subgroup of patients who received only a single dose (12 mg) of taranabant, there was a significant reduction (27%) in energy intake over 24 h, and an increase of energy expenditure (measured as a decrease in mean respiratory quotient, and suggestive of lipid metabolism) over 5 h post-dosing [75].

Table 1 Efficacy of rimonabant, a CB1 antagonist/inverse agonist, for obesity and type 2 diabetes: pooled data from the four RIO trials

The RIO-Lipids trial specifically examined the effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors, including adiponectin levels [72]. It enrolled 1,036 participants without diabetes, with untreated dyslipidaemia and a BMI between 27 and 40 kg/m2. Compared with the placebo group, participants treated with rimonabant (20 mg/day for 1 year) exhibited significant weight loss, an increase in HDL-cholesterol and a reduction in plasma triacylglycerol. Moreover, the treated participants showed significant increases in plasma adiponectin levels compared with the placebo group. This effect was ~50% independent of weight loss, which led the authors to conclude that improvements in the lipid profiles of individuals treated with rimonabant may be attributed in part to an increase in adiponectin levels.

The RIO-Diabetes trial enrolled 1,045 overweight/obese participants with type 2 diabetes. Participants had been receiving treatment with metformin or sulfonylurea monotherapy for at least 6 months, had high fasting plasma glucose levels and HbA1c levels between 6.5% and 10%. Participants treated with rimonabant (20 mg/day for 1 year) showed significant decreases in body weight and improvements in glycaemic control and HbA1c levels compared with those who received placebo [74]. The HbA1c-lowering effect of rimonabant was partly independent of weight loss. The Study Evaluating Rimonabant Efficacy in Drug-Naive Diabetic Patients (SERENADE) was conducted on 278 patients with type 2 diabetes who had HbA1c levels >7% and <10%, not adequately controlled by diet alone for a period of 6 months. Rimonabant (20 mg/day) produced significant reductions in HbA1c levels. Again, statistical analyses suggested that approximately 57% of the improvements in HbA1c levels were independent of weight loss [[76](/article/10.1007/s00125-008-1048-2#ref-CR76 "Sanofi-Aventis. New data shows Acomplia (rimonabant) benefited patients with type 2 diabetes by improving blood sugar control, reducing weight and acting on other cardiometablock risk factors. Available from http://en.sanofi-aventis.com/press/ppc_14733.asp

, Accessed April 2008.")\].Recent studies have analysed the efficacy of rimonabant using the pooled 1 year data of the four RIO trials, in one case using a meta-analysis that included two other anti-obesity drugs already on the market, sibutramine and orlistat [77, 78]. These results indicated that the CB1 antagonist might be more efficacious than these two drugs with regard to improvements in HDL-cholesterol, triacylglycerol, blood pressure and glycaemia. Another report emphasised that rimonabant produces modest but significant reductions in blood pressure in a way that, unlike the other beneficial effects of this drug, is accounted for uniquely by weight loss [79].

The safety profile of rimonabant was reported for the RIO trials, both individually [71–74] and pooled (Table 2). The data have been subject to different interpretations [78, 80], but clearly point to depressive disorders, nausea, anxiety and dizziness as the most frequent side effects leading to discontinuation. Importantly, antecedents of depression increase the risk of recurrent depressive disorders during subsequent rimonabant therapy, and severe depression and concomitant antidepressant treatment are contraindications to rimonabant prescription [65, 78]. This needs to be taken into account when prescribing CB1 antagonists to patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes, particularly since depression and anxiety are often described as accompanying these disorders, and weight loss per se can induce mood disturbances [65]. A similar, albeit not completely overlapping, safety profile emerges from the Phase II trial on taranabant [75], although in this case the smaller number of patients participating in the study did not allow any definitive conclusion to be drawn.

Table 2 Safety of rimonabant, a CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, when prescribed for obesity and type 2 diabetes: pooled data from the four RIO trials

In summary, CB1 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists are emerging as efficacious and relatively safe therapeutic drugs against not only obesity, but also type 2 diabetes and associated cardiometabolic risk factors. Future clinical studies should aim to fully demonstrate the weight loss-independent beneficial effects of such compounds and to reduce the frequency of psychiatric side effects, possibly by ensuring selection of the ideal patient for this type of treatment.

Conclusions

The scenario emerging from the reports on the EC system reviewed in this article is that ECs and CB1 receptors participate in the control of lipid and glucose metabolism at several levels, with the possible endpoint of the accumulation of energy as fat. This system becomes dysregulated following unbalanced energy intake, and it does so in several organs participating in energy homeostasis, particularly in the intra-abdominal adipose tissue, thus possibly explaining why CB1 antagonists are efficacious at reducing not only body weight but also hyperglycaemia and dyslipidaemia. Further studies are needed to fully elucidate the role, regulation and dysregulation of ECs in these organs, particularly the skeletal muscle, liver and pancreas, and to investigate EC relationships with hormones that control metabolism, including insulin and gastrointestinal neuropeptides. These studies will help to reinforce the concept of the weight loss-independent beneficial metabolic effects of CB1 antagonists, and profile the ‘ideal patient’ to be treated with these compounds.

References

- Mechoulam R (1999) Recent advances in cannabinoid research. Forsch Komplementarmed 6(3):16–20

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pertwee RG (2005) Pharmacological actions of cannabinoids. Handb Exp Pharmacol 168:1–51

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Di Marzo V, Fontana A (1995) Anandamide, an endogenous cannabinomimetic eicosanoid: ‘killing two birds with one stone’. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 53:1–11

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Di Marzo V, Petrosino S (2007) Endocannabinoids and the regulation of their levels in health and disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 18:129–140

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Liu J, Wang L, Harvey-White J et al (2008) Multiple pathways involved in the biosynthesis of anandamide. Neuropharmacology 54:1–7

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Simon GM, Cravatt BF (2008) Anandamide biosynthesis catalyzed by the phosphodiesterase GDE1 and detection of glycerophospho-_N_-acyl ethanolamine precursors in mouse brain. J Biol Chem 283:9341–9349

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Starowicz K, Nigam S, Di Marzo V (2007) Biochemistry and pharmacology of endovanilloids. Pharmacol Ther 114:13–33

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Pomelli D (2003) The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:873–84

Article CAS Google Scholar - Di Marzo V, Bifulco M, De Petrocellis L (2004) The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3:771–784

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Di Marzo V (2008) Targeting the endocannabinoid system: to enhance or reduce? Nat Rev Drug Discov 7:438–455

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Marsicano G, Moosmann B, Hermann H, Lutz B, Behl C (2002) Neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids against oxidative stress: role of the cannabinoid receptor CB1. J Neurochem 80:448–456

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hohmann AG, Suplita RL 2nd (2006) Endocannabinoid mechanisms of pain modulation. AAPS J 8:693–708

Article Google Scholar - Steiner MA, Wanisch K, Monory K et al. (2008) Impaired cannabinoid receptor type 1 signaling interferes with stress-coping behavior in mice. Pharmacogenomics J 8:196–208

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bisogno T, Di Marzo V (2007) Short- and long-term plasticity of the endocannabinoid system in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res 56:428–442

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rademacher DJ, Meier SE, Shi L, Vanessa Ho WS, Jarrahian A, Hillard CJ (2008) Effects of acute and repeated restraint stress on endocannabinoid content in the amygdala, ventral striatum, and medial prefrontal cortex in mice. Neuropharmacology 54:108–116

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG (2003) Nongenomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J Neurosci 23:4850–7

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hill MN, Carrier EJ, Ho WS et al (2008) Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment decreases cannabinoid CB1 receptor density in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 18:221–226

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L et al (2001) Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature 410:822–825

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kirkham TC, Williams CM, Fezza F, Di Marzo V (2002) Endocannabinoid levels in rat limbic forebrain and hypothalamus in relation to fasting, feeding and satiation: stimulation of eating by 2-arachidonoyl glycerol. Br J Pharmacol 136:550–557

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Matias I, Di Marzo V (2007) Endocannabinoids and the control of energy balance. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18:27–37

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cota D, Marsicano G, Tschöp M (2003) The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Invest 112:423–431

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bensaid M, Gary-Bobo M, Esclangon A et al (2003) The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 increases Acrp30 mRNA expression in adipose tissue of obese fa/fa rats and in cultured adipocyte cells. Mol Pharmacol 63:908–914

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Matias I, Gonthier MP, Orlando P et al (2006) Regulation, function, and dysregulation of endocannabinoids in models of adipose and beta-pancreatic cells and in obesity and hyperglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3171–3180

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Gasperi V, Fezza F, Pasquariello N et al (2007) Endocannabinoids in adipocytes during differentiation and their role in glucose uptake. Cell Mol Life Sci 64:219–229

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Roche R, Hoareau L, Bes-Houtmann S et al (2006) Presence of the cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, in human omental and subcutaneous adipocytes. Histochem Cell Biol 126:177–187

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Pagano C, Pilon C, Calcagno A et al (2007) The endogenous cannabinoid system stimulates glucose uptake in human fat cells via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and calcium-dependent mechanisms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:4810–4819

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Gary-Bobo M, Elachouri G, Scatton B, Le Fur G, Oury-Donat F, Bensaid M (2006) The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant (SR141716) inhibits cell proliferation and increases markers of adipocyte maturation in cultured mouse 3T3 F442A preadipocytes. Mol Pharmacol 69:471–478

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kola B, Hubina E, Tucci SA et al (2005) Cannabinoids and ghrelin have both central and peripheral metabolic and cardiac effects via AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 280:25196–25201

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Osei-Hyiaman D, Depetrillo M, Pacher P et al (2005) Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest 115:1298–1305

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Herling AW, Gossel M, Haschke G et al (2007) CB1 receptor antagonist AVE1625 affects primarily metabolic parameters independently of reduced food intake in Wistar rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293:826–832

Article CAS Google Scholar - Herling AW, Kilp S, Elvert R, Haschke G, Kramer W (2008) Increased energy expenditure contributes more to the body weight-reducing effect of rimonabant than reduced food intake in candy-fed Wistar rats. Endocrinology 149:2557–2566

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Yan ZC, Liu DY, Zhang LL et al (2007) Exercise reduces adipose tissue via cannabinoid receptor type 1 which is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-delta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354:427–433

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Murdolo G, Kempf K, Hammarstedt A, Herder C, Smith U, Jansson PA (2007) Insulin differentially modulates the peripheral endocannabinoid system in human subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue from lean and obese individuals. J Endocrinol Invest 30:17–21

Google Scholar - Zhang LL, Yan Liu D, Ma LQ et al (2007) Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 channel prevents adipogenesis and obesity. Circ Res 100:1063–1070

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Maccarrone M, Rossi S, Bari M et al (2008) Anandamide inhibits metabolism and physiological actions of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the striatum. Nat Neurosi 11:152–159

Article CAS Google Scholar - Blüher M, Engeli S, Klöting N et al (2006) Dysregulation of the peripheral and adipose tissue endocannabinoid system in human abdominal obesity. Diabetes 55:3053–3060

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Côté M, Matias I, Lemieux I et al (2007) Circulating endocannabinoid levels, abdominal adiposity and related cardiometabolic risk factors in obese men. Int J Obes (Lond) 31:692–699

Google Scholar - Gonthier MP, Hoareau L, Festy F et al (2007) Identification of endocannabinoids and related compounds in human fat cells. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15:837–845

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cavuoto P, McAinch AJ, Hatzinikolas G, Cameron-Smith D, Wittert GA (2007) Effects of cannabinoid receptors on skeletal muscle oxidative pathways. Mol Cell Endocrinol 267:63–69

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Després JP, Lemieux I (2006) Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 444:881–887

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bermudez-Silva FJ, Sanchez-Vera I, Suárez J et al (2007) Role of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in glucose homeostasis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 565:207–211

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Juan-Picó P, Fuentes E, Bermúdez-Silva FJ et al (2006) Cannabinoid receptors regulate Ca2+ signals and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cell. Cell Calcium 39:155–162

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Starowicz KM, Cristino L, Matias I et al (2008) Endocannabinoid dysregulation in the pancreas and adipose tissue of mice fed with a high-fat diet. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16:553–565

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nakata M, Yada T (2008) Cannabinoids inhibit insulin secretion and cytosolic Ca2+ oscillation in islet beta-cells via CB1 receptors. Regul Pept 145:49–53

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bermúdez-Silva FJ, Suárez J, Baixeras E et al (2008) Presence of functional cannabinoid receptors in human endocrine pancreas. Diabetologia 51:476–487

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Pagotto U, Marsicaano G, Cota D, Lutz B, Pasquali R (2006) The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr Rev 27:73–100

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cavuoto P, McAinch AJ, Hatzinikolas G, Janovská A, Game P, Wittert GA (2007) The expression of receptors for endocannabinoids in human and rodent skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 364:105–110

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - D’Eon TM, Pierce KA, Roix JJ, et al. (2008) The role of adipocyte insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of obesity-related elevations in endocannabinoids. Diabetes 57:1262–1268

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Matias I, Petrosino S, Racioppi A, Capasso R, Izzo AA, Di Marzo V (2008) Dysregulation of peripheral endocannabinoid levels in hyperglycemia and obesity: effect of high fat diets. Mol Cell Endocrinol 286(1):S66–S78

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Matias I, Carta G, Murru E, Petrosino S, Banni S, Di Marzo V (2008) Effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids on endocannabinoid and _N_-acyl-ethanolamine levels in mouse adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1781:52–60

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Monteleone P, Matias I, Martiadis V, De Petrocellis L, Maj M, Di Marzo V (2005) Blood levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide are increased in anorexia nervosa and in binge-eating disorder, but not in bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:1216–1221

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Engeli S, Böhnke J, Feldpausch M et al (2005) Activation of the peripheral endocannabinoid system in human obesity. Diabetes 54:2838–2843

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Löfgren P, Sjölin E, Wåhlen K, Hoffstedt J (2007) Human adipose tissue cannabinoid receptor 1 gene expression is not related to fat cell function or adiponectin level. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1555–1559

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Sipe JC, Waalen J, Gerber A, Beutler E (2005) Overweight and obesity associated with a missense polymorphism in fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH). Int J Obes (Lond) 29(7):755–759

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jensen DP, Andreasen CH, Andersen MK et al (2007) The functional Pro129Thr variant of the FAAH gene is not associated with various fat accumulation phenotypes in a population-based cohort of 5,801 whites. J Mol Med 85:445–449

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kempf K, Hector J, Strate T et al (2007) Immune-mediated activation of the endocannabinoid system in visceral adipose tissue in obesity. Horm Metab Res 39:596–600

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Gazzerro P, Caruso MG, Notarnicola M et al (2007) Association between cannabinoid type-1 receptor polymorphism and body mass index in a southern Italian population. Int J Obes (Lond) 31:908–912

Article CAS Google Scholar - Peeters A, Beckers S, Mertens I, Van Hul W, Van Gaal L (2007) The G1422A variant of the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) is associated with abdominal adiposity in obese men. Endocrine 31:138–141

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Russo P, Strazzullo P, Cappuccio FP et al (2007) Genetic variations at the endocannabinoid type 1 receptor gene (CNR1) are associated with obesity phenotypes in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2382–2386

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Müller TD, Reichwald K, Wermter AK et al (2007) No evidence for an involvement of variants in the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) in obesity in German children and adolescents. Mol Genet Metab 90:429–434

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Benzinou M, Chèvre J-C, Ward KJ et al (2008) Endocannabinoid receptor 1 gene variations increase risk for obesity and modulate body mass index in European populations. Hum Mol (in press) Genet DOI 10.1093/hmg/ddn089

- Perwitz N, Fasshauer M, Klein J (2006) Cannabinoid receptor signaling directly inhibits thermogenesis and alters expression of adiponectin and visfatin. Horm Metab Res 38:356–358

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Bellocchio L, Mancini G, Vicennati V, Pasquali R, Pagotto U (2006) Cannabinoid receptors as therapeutic targets for obesity and metabolic diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol 6:586–591

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kunos G (2007) Understanding metabolic homeostasis and imbalance: what is the role of the endocannabinoid system? Am J Med 120(9 Suppl 1):S18–S24

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Wright SM, Dikkers C, Aronne LJ (2008) Rimonabant: new data and emerging experience. Curr Atheroscler Rep 10:71–78

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ravinet Trillou C, Delgorge C, Menet C, Arnone M, Soubrié P (2004) CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout in mice leads to leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity and enhanced leptin sensitivity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28:640–648

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Poirier B, Bidouard JP, Cadrouvele C et al (2005) The anti-obesity effect of rimonabant is associated with an improved serum lipid profile. Diabetes Obes Metab 7:65–72

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Janiak P, Poirier B, Bidouard JP et al (2007) Blockade of cannabinoid CB1 receptors improves renal function, metabolic profile, and increased survival of obese Zucker rats. Kidney Int 72:1345–1357

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Gary-Bobo M, Elachouri G, Gallas JF et al (2007) Rimonabant reduces obesity-associated hepatic steatosis and features of metabolic syndrome in obese Zucker fa/fa rats. Hepatology 46:122–129

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Liu YL, Connoley IP, Wilson CA, Stock MJ (2005) Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 on oxygen consumption and soleus muscle glucose uptake in Lep ob/Lep ob mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 29:183–187

Article CAS Google Scholar - Van Gaal LF, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rössner S (2005) Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet 365:1389–1397

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Després JP, Golay A, Sjöström L (2005) Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N Engl J Med 353:2121–2134

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, Devin J, Rosenstock J (2006) Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 295:761–775

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Scheen AJ, Finer N, Hollander P, Jensen MD, Van Gaal LF (2006) Efficacy and tolerability of rimonabant in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled study. Lancet 368:1660–1672

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Addy C, Wright H, Van Laere K et al (2008) The acyclic CB1R inverse agonist taranabant mediates weight loss by increasing energy expenditure and decreasing caloric intake. Cell Metab 7:68–78

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Sanofi-Aventis. New data shows Acomplia (rimonabant) benefited patients with type 2 diabetes by improving blood sugar control, reducing weight and acting on other cardiometablock risk factors. Available from http://en.sanofi-aventis.com/press/ppc_14733.asp, Accessed April 2008.

- Rucker D, Padwal R, Li SK, Curioni C, Lau DC (2007) Long term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: updated meta-analysis. BMJ 335:1194–1199

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Van Gaal L, Pi-Sunyer X, Despres J-P, McCarthy C, Scheen A (2008) Efficacy and safety of rimonabant for improvement of multiple cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight/obese patients. Pooled 1-year data from the Riomonabant in Obesity (RIO) program. Diabetes Care 31(Suppl 2):S229–S240

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ruilope LM, Després JP, Scheen A et al (2008) Effect of rimonabant on blood pressure in overweight/obese patients with/without co-morbidities: analysis of pooled RIO study results. J Hypertens 26:357–367

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H, Astrup A (2007) Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 370:1706–1713

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Akiba Y, Kato S, Katsube K et al (2004) Transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 expressed in pancreatic islet beta cells modulates insulin secretion in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 321:219–225

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar