TG13 indications and techniques for gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis (with videos) (original) (raw)

Abstract

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) is considered a safe alternative to early cholecystectomy, especially in surgically high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis. Although randomized prospective controlled trials are lacking, data from most retrospective studies demonstrate that PTGBD is the most common gallbladder drainage method. There are several alternatives to PTGBD. Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration is a simple alternative drainage method with fewer complications; however, its clinical usefulness has been shown only by case-series studies. Endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage and gallbladder stenting via a transpapillary endoscopic approach are also alternative methods in acute cholecystitis, but both of them have technical difficulties resulting in lower success rates than that of PTGBD. Recently, endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transmural gallbladder drainage has been reported as a special technique for gallbladder drainage. However, it is not yet an established technique. Therefore, it should be performed in high-volume institutes by skilled endoscopists. Further prospective evaluations of the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of these various approaches are needed. This article describes indications and techniques of drainage for acute cholecystitis.

Free full-text articles and a mobile application of TG13 are available via http://www.jshbps.jp/en/guideline/tg13.html.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tokyo Guidelines (TG07) defined diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis in January 2007[1]. In the TG07, percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) should be used in patients with grade II (moderate) cholecystitis only when they do not respond to conservative treatment and for patients with grade III (severe) disease [2]. One controlled study (level C) [3] compared PTGBD with medical treatment alone and did not find lower mortality using PTGBD, but this study has several serious limitations as follows; (1) selection bias [the PTGBD group had many intensive care unit (ICU) patients] , (2) drainage methods were changed after a fatal complication, (3) randomization was achieved using a playing card and was not blinded. Thus, PTGBD, which has been endorsed by many studies of case-series but not by proper controlled trials (level C) [4–14], is the most common gallbladder drainage method for elderly and critically ill patients. There are several alternatives to PTGBD. Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration (PTGBA) is an alternative in which the gallbladder contents are puncture-aspirated without placing a drainage catheter (level C) [6, 15]. Endoscopic naso-biliary gallbladder drainage (ENGBD) and endoscopic gallbladder stenting (EGBS) are also alternatives via the transpapillary route [16]. With the recent improvement in endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), EUS-guided gallbladder drainage is performed via the antrum of the stomach and the bulbus of the duodenum [16]. However, these alternatives are not fully examined; PTGBD is still recognized as a standard drainage method.

In this article, we describe the indication and details of gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis, and show the grades of recommendation for the procedures established by the Guidelines.

Q1. What are the standard gallbladder drainage methods for surgically unfit patients with acute cholecystitis?

We recommend PTGBD as a standard drainage method according to the GRADE system [17]. Factors that affect the strength of a recommendation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 A critical comparison of drainage methods for acute cholecystitis according to GRADE system [17]

Indications and significance of PTGBD

Although early cholecystectomy, a one-shot definitive treatment for acute cholecystitis, remains the reference standard, perioperative mortality rates in elderly or critically ill patients are reported to be high (up to 19 %) [18]. Therefore, PTGBD is considered a safe alternative, especially in surgically high-risk populations. There is no doubt that PTGBD with administration of antibiotics can convert a septic cholecystitis into a non-specific condition. From a technical point of view, it is a rather uncomplicated procedure with a low complication rate reported to range from 0 to 13 % [4–12]. A systematic review [18] reports that 30-day or in-hospital mortality after PTGBD is high (15.4 %), but that procedure-related mortality is low (0.36 %). Of note, mortality is predominantly related to the severity of the underlying disease rather than the ongoing gallbladder sepsis. By contrast, mortality rates after cholecystectomy in elderly patients with acute cholecystitis have been lower than those of previous years (prior to 1995 vs. after 1995, 12.0 vs. 4.0 %) [18]. Recent advances in anesthesiology and perioperative care may have improved the outcomes of cholecystectomy for critically ill patients. There are no controlled studies evaluating the outcomes of PTGBD versus early cholecystectomy. A few papers report comparative studies in a well-defined patient group. Melloul et al. [19] analyzed a matched case-controlled study of critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis. A series of 42 consecutive patients at a single ICU center during a 7-year period were retrospectively analyzed. Surgery was associated with an increased complication rate of 47 % compared with PTGBD (8.7 %), but mortality rates were not different. One Spanish retrospective study [20] compared mortality rates in 62 consecutive patients critically ill with acute cholecystitis divided between a PTGBD group and a cholecystectomy group, and they found a significantly higher mortality rate in the PTGBD group (17.2 vs. 0 %). This study, however, has several limitations: the study design is not prospective, inclusion criteria in the PTGBD group may have selection bias because the highest-risk patients could have been treated mainly by PTGBD. These biases and shortcomings in the study design make any comparison between the outcomes of PTGBD and early cholecystectomy hazardous. Therefore, it is not possible to make definitive recommendations regarding treatment using PTGBD or cholecystectomy in elderly or critically ill patients with acute cholecystitis. Large multicenter randomized trials of PTGBD versus early cholecystectomy are undoubtedly needed to resolve these controversies.

Optimal timing of gallbladder drainage

For patients with moderate (grade II) disease, gallbladder drainage should be used only when a patient does not respond to conservative treatment. For patients with severe (grade III) disease, gallbladder drainage is recommended with intensive care. One prospective study [21] shows that predictors for failure of conservative treatment are: age above 70 years old, diabetes, tachycardia and a distended gallbladder at admission. Likewise, WBC >15000 cell/μl, an elevated temperature and age above 70 years old were found to be predictors for the failure of conservative treatment at 24-h and 48-h follow-up.

Procedures for gallbladder drainage

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (Video 1)

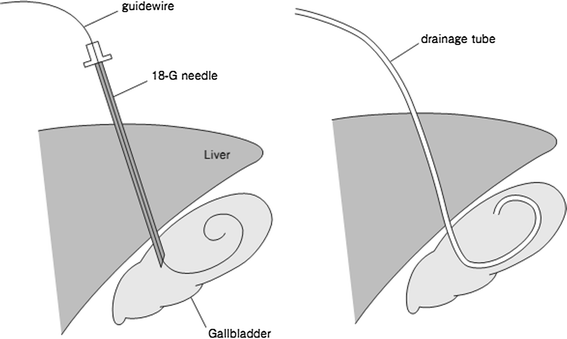

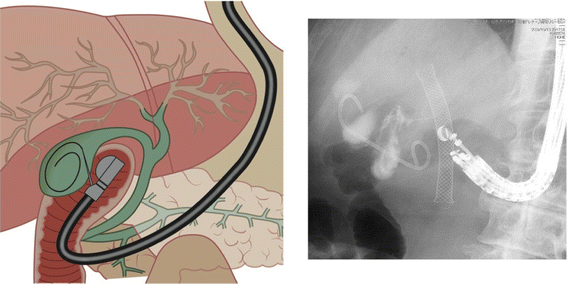

PTGBD is a standard technique for nonoperative gallbladder drainage. After ultrasound-guided transhepatic gallbladder puncture has been performed with an 18-G needle, a 6- to 10-Fr pigtail catheter is placed in the gallbladder, using a guidewire under fluoroscopy (Seldinger technique; Fig. 1). There was no technical difficulty and the technique could be available around the world (Table 1). However, it has several disadvantages as follows: (1) the drainage tube cannot be extracted until a fistula forms around the tube, (2) there is a risk of dislocation of the tube, (3) patient discomfort may cause self-decannulation of the PTGBD tube.

Fig. 1

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) procedure. A guidewire is inserted into the gallbladder after a needle is inserted into the gallbladder (left). Then a drainage tube is passed over the guide-wire into the gallbladder (right)

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration

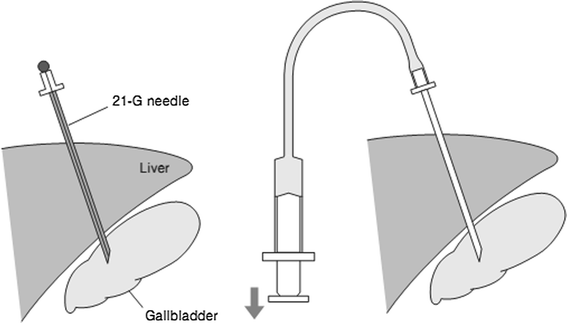

PTGBA is a method to aspirate bile via the gallbladder with a small-gauge needle under ultrasonographic guidance (Fig. 2). This method is an easy low-cost bedside-applicable procedure, without the patient discomfort seen in PTGBD (Table 1). Theoretically, the drainage effect of single PTGBA is lower than that of PTGBD as described in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [12]. However, repetitive PTGBA [6, 15] can improve its effectiveness (from 71.1 to 95.6 %) and this methodology has not been compared with PTGBD. Although PTGBA with a small-gauge (21-G) needle has a lower risk of leakage after removal, aspiration of highly viscous bile is difficult with such needles and should be conducted while washing with saline containing antibiotics.

Fig. 2

Percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration (PTGBA) procedure. Under ultrasound guidance, the gallbladder is punctured transhepatically by a needle (left). Then bile is aspirated by using a syringe (right)

Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage

Endoscopic naso-biliary gallbladder drainage (Video 2)

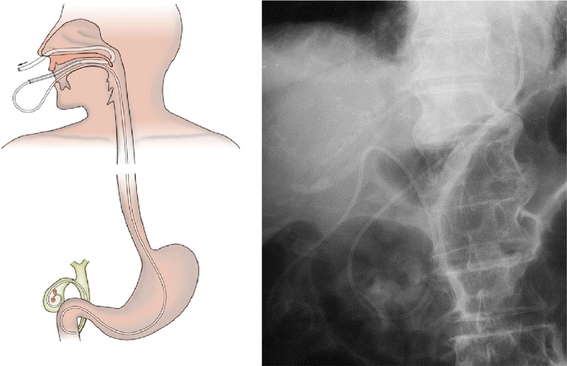

ENGBD can be used for patients with severe comorbid conditions, especially those with end-stage liver disease, in whom the percutaneous approach is difficult to perform. However, because it requires a difficult endoscopic technique (technical success rate varies from 64 to 100 %), and relevant case-series studies have been conducted only at a limited number of institutions [22–28], ENGBD has not yet been established as a standard method. Therefore, it should be performed in high-volume institutes by skilled endoscopists.

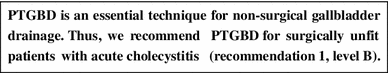

ENGBD involves placement of a naso-gallbladder drainage tube and generally does not require biliary sphincterotomy. After successful bile duct cannulation, a 0.035-in. guidewire is advanced into the cystic duct and subsequently into the gallbladder. At times, a hydrophilic guidewire is useful for seeking the cystic duct. Finally, a 5–8.5 Fr pigtail naso-gallbladder drainage tube catheter is placed into the gallbladder (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Endoscopic nasobiliary gallbladder drainage (ENGBD) procedure. Left Schema of ENGBD. Right X-ray shows nasobiliary catheter placed in the gallbladder

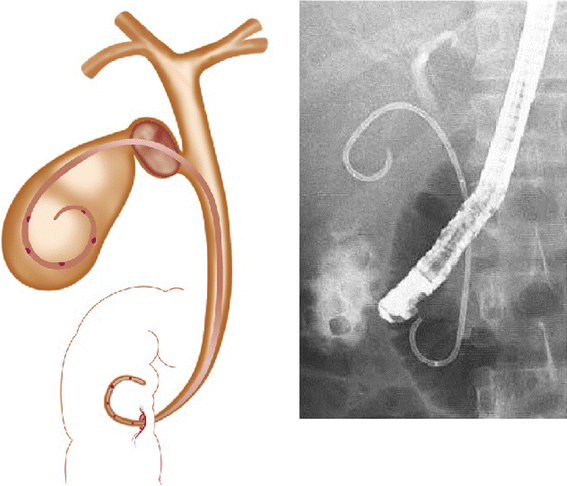

Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder stenting

Since endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder stenting (EGBS) requires a difficult endoscopic technique, and relevant case-series studies have been conducted only at a limited number of institutions [29–36], EGBS also has not been established as a standard method. Therefore, it should be performed in high-volume institutes by skilled endoscopists. The procedure is identical to ENGBD, but a 6–10-Fr diameter double pigtail stent is placed (Fig. 4). When 10-Fr stents or a gallbladder stent and a biliary stent are placed (for example in Mirizzi’s syndrome), an endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy is performed to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Fig. 4

Endoscopic gallbladder stenting (EGBS) procedure. Left Schema of EGBS. Right X-ray shows double-pig tail stent placed in the gallbladder

Q2. What are the special techniques as gallbladder drainage?

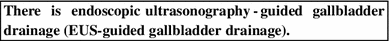

EUS-guided gallbladder drainage is performed via the antrum of the stomach and bulbus of the duodenum (Fig. 5) [16, 42]. It includes EUS-guided naso-gallbladder drainage [37, 38] and EUS-guided gallbladder stenting [39, 44] (Table 2). Recently one controlled study [42] showed that EUS-GBD is comparable to PTGBD in terms of the technical feasibility and efficacy. However, EUS-guided gallbladder drainage has not been established as a standard method. Therefore, they should be performed in high-volume institutes by skilled endoscopists [37–46].

Fig. 5

EUS-guided gallbladder approach via bulbus of the duodenum. Left Schema of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage. Right X-ray shows double-pig tail stent placed in the gallbladder

Table 2 Outcome of endosonography-guided gallbladder drainage

Technique of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage [16, 44] (Video 3)

Theoretically, the gallbladder does not have adhesions to the GI tract. Therefore, there is a possibility of bile leakage during the procedures; in particular, if the procedure fails, serious bile peritonitis can occur. The choice of endoscope position is important to accomplish the procedure safely. The gallbladder is visualized from the duodenal bulb or the antrum of the stomach using a curved linear array echoendoscope in a long scope position (pushing scope position) (Fig. 5). At this time, the direction of the EUS probe is toward the right side of the body. A needle knife (Zimmon papillotomy knife, or Cystotome, Wilson-Cook, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) catheter using electrocautery, or a 19-gauge needle (EchoTip, Wilson-Cook), is advanced into the gallbladder under EUS visualization after confirming the absence of intervening blood vessels to avoid bleeding. After the stylet has been removed, first bile is aspirated and then contrast medium is injected into the gallbladder for cholecystography, then a 0.025- or 0.035-in. guidewire is advanced into the outer sheath. If necessary, a biliary catheter for dilation (Soehendra Biliary Dilator, Wilson-Cook), or papillary balloon dilation catheter (Maxpass, Olympus Medical Systems) are used for dilation of the gastrocholecystic and duodenocholecystic fistula. Finally, a 5-10 Fr naso-gallbladder tube is advanced via the cholecystogastrostomy and cholecystoduodenostomy site into the gallbladder. The basic procedure of EUS-guided gallbladder stenting is the same as EUS-guided naso-gallbladder drainage. A 7-10Fr double pigtail plastic or self-expanding metallic stent is placed in the final step.

There have been 9 retrospective and 1 prospective analyses on 3 EUS-guided naso-gallbladder drainages and 7 EUS-guided gallbladder stentings (4 plastic stent, 3 self-expanding metal stent) (Table 2). The success rates and response rates of both procedures were approximately 100 %, but the incidence of accidents was fairly high (11–33 %), indicating the necessity for further investigations emphasizing safety evaluation. There are several possible procedure-related early adverse events, e.g., bile leakage, stent migration into the gallbladder or intra-abdominal space, deviation of stent from the gallbladder, puncture-induced hemorrhage, and perforation of peritoneum. Late adverse events include relapse of acute cholecystitis due to stent occlusion, and inadvertent tube removal.

References

- Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Hirata K, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:78–82.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Wada K, Nagino M, et al. Techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:46–51 (clinical practice guidelines, CPGs).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hatzidakis AA, Prassopoulos P, Petinarakis I, Sanidas E, Chrysos E, Chalkiadakis G, et al. Acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy vs conservative treatment. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1778–84 (CPGs).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kiviniemi H, Makela JT, Autio R, Tikkakoski T, Leinonen S, Siniluoto T, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: an analysis of 69 patients. Int Surg. 1998;83:299–302.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Sugiyama M, Tokuhara M, Atomi Y. Is percutaneous cholecystostomy the optimal treatment for acute cholecystitis in the very elderly? World J Surg. 1998;22:459–63.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Chopra S, Dodd GD 3rd, Mumbower AL, Chintapalli KN, Schwesinger WH, Sirinek KR, et al. Treatment of acute cholecystitis in non-critically ill patients at high surgical risk: comparison of clinical outcomes after gallbladder aspiration and after percutaneous cholecystostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1025–31.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Akhan O, Akinci D, Ozmen MN. Percutaneous cholecystostomy. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:229–36.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Donald JJ, Cheslyn-Curtis S, Gillams AR, Russell RC, Lees WR. Percutaneous cholecystolithotomy: is gall stone recurrence inevitable? Gut. 1994;35:692–5.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Hultman CS, Herbst CA, McCall JM, Mauro MA. The efficacy of percutaneous cholecystostomy in critically ill patients. Am Surg. 1996;62:263–9.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Melin MM, Sarr MG, Bender CE, van Heerden JA. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: a valuable technique in high-risk patients with presumed acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1274–7.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Davis CA, Landercasper J, Gundersen LH, Lambert PJ. Effective use of percutaneous cholecystostomy in high-risk surgical patients: techniques, tube management, and results. Arch Surg. 1999;134:727–31.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Sugawara T, et al. Percutaneous cholecystostomy versus gallbladder aspiration for acute cholecystitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:193–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Babb RR. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:238–41.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Lillemoe KD. Surgical treatment of biliary tract infections. Am Surg. 2000;66:138–44.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Tsutsui K, Uchida N, Hirabayashi S, Kamada H, Ono M, Ogawa M, et al. Usefulness of single and repetitive percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration for the treatment of acute cholecystitis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:583–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Itoi T, Coelho-Prabhu N, Baron TH. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage for management of acute cholecystitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1038–45.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;17(336):1106–10.

Article Google Scholar - Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J, Sandstrom P. Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:183–93.

Article Google Scholar - Melloul E, Denys A, Demartines N, Calmes JM, Schafer M. Percutaneous drainage versus emergency cholecystectomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis in critically ill patients: does it matter? World J Surg. 2011;35:826–33.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Rodriguez Sanjuan JC, Arruabarrena A, Sanchez Moreno L, Gonzalez Sanchez F, Herrera LA, Gomez Fleitas M. Acute cholecystitis in high surgical risk patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy or emergency cholecystectomy? Am J Surg. 2012;204(1):54–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Barak O, Elazary R, Appelbaum L, Rivkind A, Almogy G. Conservative treatment for acute cholecystitis: clinical and radiographic predictors of failure. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009;11:739–43.

PubMed Google Scholar - Baron TH, Schroeder PL, Schwartzberg MS, Carabasi MH. Resolution of Mirizzi’s syndrome using endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:343–5.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Feretis C, Apostolidis N, Mallas E, Manouras A, Papadimitriou J. Endoscopic drainage of acute obstructive cholecystitis in patients with increased operative risk. Endoscopy. 1993;25:392–5.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Ishii K, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis in whom percutaneous transhepatic approach is contraindicated or anatomically impossible (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:455–60.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kjaer DW, Kruse A, Funch-Jensen P. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage of patients with acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:304–8.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Nakatsu T, Okada H, Saito K, Uchida N, Minami A, Ezaki T, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage (ETGBD) for the treatment of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1997;4:31–5.

Article Google Scholar - Ogawa O, Yoshikumi H, Maruoka N, Hashimoto Y, Kishimoto Y, Tsunamasa W, et al. Predicting the success of endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage for patients with acute cholecystitis during pretreatment evaluation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:681–5.

PubMed Google Scholar - Toyota N, Takada T, Amano H, Yoshida M, Miura F, Wada K. Endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage in the treatment of acute cholecystitis: alleviates inflammation and fixes operator’s aim during early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:80–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Conway JD, Russo MW, Shrestha R. Endoscopic stent insertion into the gallbladder for symptomatic gallbladder disease in patients with end-stage liver disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:32–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Gaglio PJ, Buniak B, Leevy CB. Primary endoscopic retrograde cholecystoendoprosthesis: a nonsurgical modality for symptomatic cholelithiasis in cirrhotic patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:339–42.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Kalloo AN, Thuluvath PJ, Pasricha PJ. Treatment of high-risk patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis by endoscopic gallbladder stenting. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:608–10.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Pannala R, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Baron TH. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage: 10-year single center experience. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2008;54:107–13.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Schlenker C, Trotter JF, Shah RJ, Everson G, Chen YK, Antillon D, et al. Endoscopic gallbladder stent placement for treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis in patients with end-stage liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:278–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Shrestha R, Bilir BM, Everson GT, Steinberg SE. Endoscopic stenting of gallbladder for symptomatic cholelithiasis in patients with end-stage liver disease awaiting orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:595–8.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Tamada K, Seki H, Sato K, Kano T, Sugiyama S, Ichiyama M, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholecystoendoprosthesis (ERCCE) for cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 1991;23:2–3.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Johlin FC Jr, Neil GA. Drainage of the gallbladder in patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis by transpapillary endoscopic cholecystotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:645–51.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kwan V, Eisendrath P, Antaki F, Le Moine O, Deviere J. EUS-guided cholecystoenterostomy: a new technique (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:582–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Lee SS, Park DH, Hwang CY, Ahn CS, Lee TY, Seo DW, et al. EUS-guided transmural cholecystostomy as rescue management for acute cholecystitis in elderly or high-risk patients: a prospective feasibility study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1008–12.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Baron TH, Topazian MD. Endoscopic transduodenal drainage of the gallbladder: implications for endoluminal treatment of gallbladder disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:735–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Takasawa O, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Ito K, Horaguchi J, et al. Endosonography-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis following covered metal stent deployment. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:43–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Song TJ, Park do H, Eum JB, Moon SH, Lee SS, Seo DW, et al. EUS-guided cholecystoenterostomy with single-step placement of a 7F double-pigtail plastic stent in patients who are unsuitable for cholecystectomy: a pilot study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:634–40.

Google Scholar - Itoi T, Itokawa F, Kurihara T. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage: actual technical presentations and review of the literature (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:282–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Jang JW, Lee SS, Park do H, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, et al. Feasibility and safety of EUS-guided transgastric/transduodenal gallbladder drainage with single-step placement of a modified covered self-expandable metal stent in patients unsuitable for cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:176–81.

Google Scholar - Itoi T, Binmoeller, Shah J, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:870–6.

- Jang JW, Lee SS, Song TJ, Hyun YS, Park do H, Seo DW, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):805–11.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kamata K, Kitano M, Komaki T, Sakamoto H, Kudo M. Transgastric endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2):E315–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Medicine and Clinical Oncology, Graduate School of Medicine Chiba University, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo-ku, Chiba, 260-8677, Japan

Toshio Tsuyuguchi - Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Takao Itoi - Department of Surgery, Teikyo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan

Tadahiro Takada & Fumihiko Miura - Section of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Washington University in Saint Louis School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA

Steven M. Strasberg - Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Henry A. Pitt - Department of Internal Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan, Seoul, Korea

Myung-Hwan Kim - Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Seth G S Medical College and K E M Hospital, Mumbai, India

Avinash N. Supe - Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Ichinomiya Municipal Hospital, Ichinomiya, Japan

Toshihiko Mayumi - Clinical Research Center Kaken Hospital, International University of Health and Welfare, Ichikawa, Japan

Masahiro Yoshida - Center for Clinical Infectious Diseases, Jichi Medical University, Shimotsuke, Tochigi, Japan

Harumi Gomi - Department of Surgical Oncology and Gastroenterological Surgery, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan

Yasutoshi Kimura - Department of Surgery, Institute of Gastroenterology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Ryota Higuchi - Department of Surgery, Kitakyushu Municipal Yahata Hospital, Kitakyushu, Japan

Kohji Okamoto - Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Fukuoka University School of Medicine, Fukuoka, Japan

Yuichi Yamashita - Department of Radiology, Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medical Science, Kanazawa, Japan

Toshifumi Gabata - Department of Endoscopy and Ultrasound, Kawasaki Medical School, Okayama, Japan

Jiro Hata - Department of Surgery, Toho University Medical Center Ohashi Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Shinya Kusachi

Authors

- Toshio Tsuyuguchi

- Takao Itoi

- Tadahiro Takada

- Steven M. Strasberg

- Henry A. Pitt

- Myung-Hwan Kim

- Avinash N. Supe

- Toshihiko Mayumi

- Masahiro Yoshida

- Fumihiko Miura

- Harumi Gomi

- Yasutoshi Kimura

- Ryota Higuchi

- Kohji Okamoto

- Yuichi Yamashita

- Toshifumi Gabata

- Jiro Hata

- Shinya Kusachi

Corresponding author

Correspondence toToshio Tsuyuguchi.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (MPG 20524 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (MPG 18676 kb)

Supplementary material 3 (MPG 15470 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuyuguchi, T., Itoi, T., Takada, T. et al. TG13 indications and techniques for gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis (with videos).J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20, 81–88 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-012-0570-2

- Published: 11 January 2013

- Issue date: January 2013

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-012-0570-2

Keywords

Supplementary material 1 (MPG 20524 kb) Supplementary material 2 (MPG 18676 kb) Supplementary material 3 (MPG 15470 kb)