The COMET Handbook: version 1.0 (original) (raw)

2.1 Background

The development of a COS in health care involves working with key stakeholders to prioritise large numbers of outcomes and achieve consensus as to the core set. Various methods have been used to develop a COS and it is uncertain which are most suitable, accurate and efficient. Research to identify optimal methods of developing COS is ongoing and there is currently wide variation in the approaches used [14]. Methods include the Delphi technique [48, 49], nominal group technique [50, 51], consensus development conference [52] and semistructured group discussion [53]. Many studies have used a combination of methods to reach consensus’ for example, Ruperto et al. [54] used the Delphi approach followed by the nominal group technique at a face-to-face meeting, whilst Harman et al. [55], Potter et al. [56], van’t Hooft et al. [57] and Blazeby et al. [58] used the Delphi approach followed by face-to-face semistructured discussion.

One example where consensus work has been undertaken in two different ways is in paediatric asthma. The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society employed an expert panel approach [59], whereas other researchers combined results from a Delphi survey with clinicians and interviews with parents and children [60]. The results were overlapping but not identical. Female sexual dysfunction is another disease area where different methods have been used to obtain consensus. In one study, a literature review was undertaken and critiqued by experts [61], whereas in another study, a modified Delphi method was used to develop consensus definitions and classifications [62]. Both studies resulted in the same primary outcome; however, secondary outcomes differed. Similarly, multiple COS have also been developed for systemic lupus erythematosus. OMERACT adopted a nominal group process to rank outcome domains [63], whereas EULAR adopted a consensus building approach [64]. The results from both studies were very similar, with EULAR recommending other additional outcomes.

COS developers have identified that methodological guidance for COS development would be helpful [[65](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR65 "Gargon EA. Developing the agenda for core outcome set development. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool. 2016. https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3001398/

.")\]. There is limited empirical evidence, however, regarding whether different methods lead to similar or different conclusions, and there is a need to develop evidence-based approaches to COS development.The OMERACT Handbook is a useful resource for those wishing to develop COS in the area of rheumatology under the umbrella of the OMERACT organisation [[46](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR46 "Boers M, et al. The OMERACT Handbook. 2015. Available from: https://www.omeract.org/pdf/OMERACT_Handbook.pdf

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\]. We have previously identified issues to be considered in the development of COS more generally \[[21](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR21 "Williamson PR, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13(1):132.")\] and expand on those here, together with additional ones identified since this earlier publication. We present information about how COS developers have tackled these issues using data from our previous systematic reviews \[[14](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR14 "Gargon E, et al. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99111."), [39](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR39 "Gorst SL, et al. Choosing Important Health Outcomes for Comparative Effectiveness Research: An Updated Review and User Survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146444.")\] and describe results from methodological research studies where available.In the systematic review (227 COS identified), 63% of studies made recommendations about what to measure only. Some of the remaining studies also made recommendations about how to measure the outcomes that they included in their core set, with 35% of studies doing this as a single process, considering both what to measure and how to measure. The remaining 2% of studies in the systematic review of COS considered what to measure and how to measure outcomes included in the core set as a two-stage process, first considering what to measure and then considering how to measure. Thus, there appears to be consistency in that the first step in the process is typically to gain agreement about ‘what’ to measure, with decisions about ‘how’ and ‘when’ to measure these outcomes usually later in the process. This two-stage process has the advantage of being able to identify gaps where further research would be needed, e.g. if an outcome is deemed to be of core importance but no outcome measurement instrument exists with adequate psychometric properties.

This chapter provides guidance on developing consensus about what to measure, i.e. a COS, and provides recommendations for finding and selecting instruments for measuring the outcomes in the core set, i.e. the how.

2.2 Scope of a core outcome set

The scope of a COS refers to the specific area of health or health care of interest to which the COS is to be applied. The scope should be described in terms of the health condition, target population and interventions that the COS is to be applicable to, thus covering the first three elements of the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) structure for a clinical trial.

This can be one of the most difficult aspects of the process, but clarity from the outset will likely reduce later problems of misinterpretation and ambiguity. This will help to focus the development of the COS and help potential users decide on its relevance to their work.

2.2.1 Health condition and target population

For example, in prostate cancer, a COS may be developed for all patients or it may focus on patients with localised disease.

2.2.2 Interventions

For example, a COS may be created for use in all trials of interventions to treat localised prostate cancer or just for surgery.

Of the 227 COS published up to the end of 2014, 53% did not specify whether the COS was intended for all interventions or a particular intervention type, 7% were for any intervention, and 40% were for a specific intervention type.

2.2.3 Setting

The focus of this Handbook is on the development of COS for effectiveness trials. A distinction is made between efficacy and effectiveness trials, since developing a COS to cover both designs may lead to difficulties with respect to particular domains such as health care resource use [48]. COS are equally applicable in other settings; for example, routine clinical practice (see ‘Chapter 4’).

2.3 Establishing the need for a core outcome set

2.3.1 Does a relevant core outcome set already exist?

The first thing to do is find out whether a relevant COS exists by reviewing the academic literature.

One of the difficulties in this area of research has been to identify whether studies have already been done, or are underway, to develop a COS. The COMET Initiative has developed an online searchable database, enabling researchers to check for existing or ongoing work before embarking on a new project, thus minimising unnecessary duplication of effort. A video of ‘How to search the COMET database’ can be found on the COMET website [[66](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR66 "COMET. How to search the COMET Initiative database. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: https://stream.liv.ac.uk/eqyg4t36

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].The COMET database is populated through an annual systematic review update of published studies, and by COS developers registering their new projects. To avoid missing any ongoing projects not yet registered in the COMET database, it is recommended that researchers contact other experts in the particular health condition, as well as the COMET project coordinator, to check whether any related work is ongoing. It may also be prudent to apply the COMET search strategy [14] with additional filter terms for the area of interest for the recent period since the last COMET annual update.

Although there may be no exact match for the scope of interest, it may be that a related COS exists, e.g. a COS for all interventions in the condition of interest has been developed but a COS for a specific intervention type is sought, or a COS was developed by relevant stakeholders in countries other than that of the team with the current interest, or a COS was developed with the same scope but did not involve obtaining patients’ views.

2.3.2 Is a core outcome set needed?

If a relevant COS does not exist, a review of previous trials [67] or systematic reviews [68] in the area can provide evidence of need for a COS. Systematic reviewers are starting to use the outcome matrix recommended by the ORBIT project [69] to display the outcomes reported in the eligible studies. This matrix may demonstrate inconsistency of outcomes measured to date in addition to potential outcome-reporting bias.

The rest of this chapter is written from the premise that the development of a new COS is warranted. If a COS already exists, but the quality could be improved by additional work related to particular stakeholder groups, countries, or alternative consensus methods, then certain sections below will also be of relevance. The issue of quality assessment is discussed in ‘Quality assessment/critical appraisal’ below and in ‘Chapter 4’.

2.3.3 Avoiding unnecessary duplication of effort

The COMET database is a useful resource for researchers to see what work has been done in their area of interest and for research funders wishing to avoid unnecessary duplication of effort when supporting new COS activities, as illustrated by the following two examples.

Example 1

In September 2014 Valerie Page (Watford General Hospital, UK) contacted COMET via the website to register the development of a COS in delirium. We followed up the request for additional information so that we could register this in the database, and in the meantime we logged this on the private non-database list that we use to keep track of work that we know about prior to inclusion in the database. Whilst waiting for this information to be returned, in May 2015 we received a second request for registration of COS development in the same clinical area by Louise Rose from the University of Toronto, Canada. The researchers were unaware of each other’s work. We got in touch with both researchers and asked for permission to share details of their work, as well as to pass on contact details. In September 2015 we received confirmation that Louise Rose and Valerie Page, with the European Delirium Association and American Delirium Society, are now working collaboratively on this. Details of this collaborative effort to develop a COS for delirium can be found in the database [[70](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR70 "Rose L, Page V. Developing a core outcome set for delirium prevention and/or treatment trials. [cited 2016 April ]. Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/796

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].Example 2

Benjamin Allin (University of Oxford, UK) started planning a study to develop a COS for infants with gastroschisis in early 2015. He checked the COMET database to see if a COS existed, but nothing was registered at that time. He contacted COMET in September 2015 to register his project. On receiving this request, the COMET project coordinator checked the COMET database to find out if there was any relevant work in this area and identified an ongoing study registered in this same area of gastroschisis. This latter work had been registered by Nigel Hall (University of Southampton and Southampton Children’s Hospital, UK) in June 2015. Again, the two groups were put in touch, and they met up to discuss the proposed core sets, which resulted in a plan being drawn up for collaboration to work together to produce one COS rather than two. The existing gastroschisis COS entry in the database has been updated to reflect this collaborative effort [[71](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR71 "Allin B, et al. Developing a core outcome set (COS) for infants born with gastroschisis. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/746

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].2.4 Study protocol

There are potential sources of bias in the COS development process, and preparing a protocol in advance may help to reduce these biases, improve transparency and share methods with others. We recommend that a protocol be developed prior to the start of the study, and made publically available, either through a link on the COMET registration entry or a journal publication [72,73,74]. In a similar way to the development of the SPIRIT guidance for clinical trial protocols, there is a need to agree protocol content.

2.5 Project registration

One of the aims of the COMET Initiative is to provide a means of identifying existing, ongoing and planned COS studies. COS developers should be encouraged to register their project in a free-to-access, unrestricted public repository, such as the COMET database, which is the only such repository we are aware of.

The following information about the scope and methods used is recorded in the database for existing and ongoing work:

- Clinical areas for which the outcomes are being considered, identifying both primary disease and types of intervention

- Target population (age and sex), and any other details about the population within the health area

- Setting for intended use (e.g. research and/or practice)

- Method of development to be used for the COS

- People and organisations involved in identifying and selecting the outcomes, recording how the relative contributions will be used to define the COS

Details of any associated publications, including the protocol and the final report, can be recorded in the COMET database, added to the original COMET registration page.

2.6 Stakeholder involvement

It is important to consider which groups of people should be involved in deciding which outcomes are core to measure, and why. Bringing diverse stakeholders together to try to reach a consensus is seen to be the future of collaborative, influential research.

Key stakeholders may include health service users, health care practitioners, trialists, regulators, industry representatives, policy-makers, researchers and the public. Decisions regarding the stakeholder groups to be involved, how they are to be identified and approached, and the number from each group will be dependent upon the particular scope of the COS as well as upon existing knowledge, the methods of COS development to be used, and practical feasibility considerations. For example, a COS for an intervention that aims to improve body image, e.g. breast reconstruction following mastectomy, is likely to have predominantly patients as the key stakeholders [56].

The stages of involvement during the process should also be considered for each stakeholder group. For example, it may be considered appropriate to involve methodologists in determining how to measure particular outcomes, but not to be involved in determining what to measure. These decisions should be documented and explained in the study protocol.

Consideration should be given to the representativeness of the sample of stakeholders and the ability of people across the different groups to engage with the chosen consensus method (including online activities and face-to-face meetings).

Consideration should be given to potential conflicts of interest within the group developing the COS (for example, the developers of measurement instruments in the area of interest or those whose work is focussed on a specific outcome).

2.6.1 Patient and public involvement and participation

COMET recognises the expertise and crucial contribution of patients and carers in developing COS. COS need to include outcomes that are most relevant to patients and carers, and the best way to do this is to include them in COS development. Examples exist where patients have identified an outcome important to them as a group that might not have been considered if the COS had been developed by practitioners on their own [75, 76]. However, it is worth noting that examples also exist where health professionals have identified areas that patients were reluctant to talk about in focus groups; for example, sexual health [77].

2.6.1.1 Patient and public participation

We refer to patients taking part in the COS study as ‘research participants’ and the activity as research ‘participation’. People involved in a COS study as research participants give their views on the importance of outcomes and may also subsequently be asked their opinion on how those outcomes are to be measured.

Of the 227 COS that had been published up to the end of December 2014, 44 (19%) studies reported including patient participants in the COS development process. However, of these 44 COS, only 26 (59%) studies provided details of how patients had participated in the development process. The most commonly used methods to include patient participants were the Delphi technique and semistructured group discussion which were used in 38% and 35% of studies, respectively. Three of the 26 (12%) COS studies were developed with only patients as participants. Of the remaining 23 studies, patients participated alongside clinicians during the development process in 19 (83%) studies, as compared to two (9%) studies where patients and clinicians participated separately throughout the whole development process. In the two remaining studies, patients and clinicians participated separately in the initial stages, but then alongside side each other during the final stages of the development process. For the 21 studies where patients and clinicians did participate alongside each other for all or part of the COS development process, the percentage of patient participants included ranged from 4 to 50%.

Of ongoing COS studies (n = 127 as of 12 April 2016), 88% now include patients as participants. The question now is not whether patients should participate, but rather the nature of that participation. It is recommended that both health professionals and patients be included in the decision-making process concerning what to measure, as the minimum, unless there is good reason to do otherwise. ‘Qualitative methods in core outcome set development’ below discusses considerations to enhance patient participation in a COS.

2.6.1.2 Patient and public involvement

When planning a COS study that involves patients as research participants, it is important to also involve patients in designing the study. We refer to patients who are involved in designing and overseeing a COS study as ‘public research partners’ and this activity as ‘patient involvement’. PPI has been defined as where research is ‘being carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them’ [[78](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR78 "INVOLVE. What is public involvement in research? 2016. [cited 2016 19 March]. Available from: http://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].Involving public research partners in both the design and oversight of the COS development study may have the potential to:

- Provide advice on the best ways of identifying and accessing particular patient populations

- Inform discussions about ethical aspects of the study

- Facilitate the design of more appropriate study information

- Promote the development of more relevant materials to promote the study

- Enable ongoing troubleshooting opportunities for patient participation issues during the study, e.g. recruitment and retention issues of study participants

- Inform the development of a dissemination strategy of COS study results for patient participants and the wider patient population

- Ensure that your COS is relevant to patients and, crucially, that patients see it to be relevant and can trust that the development process has genuinely taken account of the patient perspective.

Involving public research partners in designing and overseeing the COS study requires that researchers plan for this involvement. They might choose different methods of doing this; for example, they might have one or two discussion groups in the planning stage and then ongoing involvement of one or two public contributors on the Study Advisory Group (SAG). For example, Morris et al. (2015) engaged parents at various stages of the research process and consulted with parents from their ‘Family Faculty’ in designing a plain language summary of the results of their COS [79]. Numerous resources now exist to help researchers to plan and budget for PPI in research; for example: in the UK, INVOLVE have numerous resources [[80](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR80 "INVOLVE. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.invo.org.uk/

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].COMET has also produced a checklist for COS developers to consider with public research partners when planning their COS study. These can be found on the COMET website.

2.7 Determining ‘what’ to measure – the outcomes in a core outcome set

2.7.1 Identifying existing knowledge about outcomes

It is recommended that potential relevant outcomes are identified from existing work to inform the consensus process. There are three data sources that should be considered: systematic reviews of published studies, reviews of published qualitative work, investigation into items collected in national audit data sets and interviews or focus groups with key stakeholders to understand their views of outcomes of importance. Depending on the resources available, protocols within clinical trial registries may also be a useful source of information.

2.7.1.1 Systematic review of outcomes in published studies

Systematic reviews are advantageous because they can efficiently identify an inclusive list of outcomes being reported by researchers in a given area. Nevertheless, it is important to note that systematic reviews of outcomes just aggregate the opinions of the previous researchers on what outcomes they deemed important to measure; hence the need for subsequent consensus development to agree with the wider community of stakeholders what outcomes should be included in a COS.

The scope of the systematic review should be carefully considered in the context of the COS to ensure that outcomes are included from all relevant studies without unnecessary data collection. The clinical area should be clearly defined and appropriate databases accessed accordingly. Commonly used databases include Medline, CINAHL, Embase, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and PsycINFO. In the systematic reviews of COS [14, 39], 57 (25%) studies carried out a review of outcomes [[65](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR65 "Gargon EA. Developing the agenda for core outcome set development. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool. 2016. https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3001398/

.")\]. The number of databases searched was not reported for 17 studies (30%), and two studies did not perform an electronic database search. Thirty-eight studies described which databases they searched (Table [1](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#Tab1)).Table 1 Description of databases searched (n = 38)

There is no recommended time window to conduct systematic reviews. Some COS studies may examine all the available academic literature. This may be an enormous task in common disease areas. Scoping searches are useful to determine the number of identified studies for a specific area. Overly large reviews are resource intensive and may not yield important additional outcomes. One strategy is to perform the systematic review in stages to check if outcome saturation is reached. For example, a review of trials published over the last 5 years may be conducted initially and the outcomes extracted. The search may then extended, and the additional outcomes checked against the original list. If there are no further outcomes of importance then the systematic review may be considered complete. For most areas a recent search is recommended as a minimum (e.g. the past 24 months) to capture up-to-date developments and outcomes relevant to that COS. Seventeen studies in the systematic reviews of COS (30%) did not state the date range searched. Seven studies (12%) did not apply any date restrictions to their search. The number of years reported in the remaining 33 studies ranged between 2 and 59. Frequencies are provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Number of years searched (n = 33)

Data extraction should be considered in terms of:

- Study characteristics

- Outcomes

- Outcome measurement instruments and/or definitions provided by the authors for each outcome

In terms of outcome extraction from the academic literature, it is recommended that all are extracted verbatim from the source manuscript [81]. This transparency is important to allow external critical review of the COS right back to its inception. In addition, extraction of outcome definitions supplied by, and measurement instruments used by, the authors is recommended as this will inform the selection of the outcome measurement set which will occur at a later stage. This is necessary because outcome definitions may vary widely between investigators and it is often not clear as to what outcomes are measuring [67, 82,83,84].

2.7.1.2 How to extract outcomes from the academic literature to inform the questionnaire survey

It is likely that some outcomes will be the same but will have been defined or measured in different publications in various ways. For example, in a review of outcomes for colorectal cancer surgery some 17 different definitions were identified for ‘anastomotic leakage’ [85]. The first step is to group these different definitions together (extracting the wording description verbatim) under the same outcome name. Similarly, in a review of outcomes for weight loss surgery, it was apparent that different terminology is used for weight loss itself in the academic literature [84]. The 41 different outcome assessments referring to weight were all categorised into one item for a subsequent Delphi questionnaire survey.

The next step is to group these outcomes into outcome domains, constructs which can be used to classify broad aspects of the effects of interventions, e.g. functional status. Outcomes from multiple domains may be important to measure in trials, and several outcomes within a domain may be relevant or important. Initially researchers create outcome domains for each outcome to be grouped into (see ‘Ontologies for grouping individual outcomes into outcome domains’ below). The domains need discussion and to be agreed by the team for the list to be categorised. Each outcome will then be mapped to a domain (independently) and this will provide transparency. For example, in a systematic review of studies evaluating the management of otitis media with effusion in children with cleft palate, a total of 43 outcomes were listed under 13 domain headings (see Table 18 in [81]).

Categorisation of each verbatim outcome definition to an outcome name, and each outcome name to an outcome domain is recommended to be performed independently by two researchers from multiprofessional backgrounds. This may include expert health service researchers, clinicians (e.g. surgeons, dietician, nurses, health psychologists) and methodologists. Where two researchers work on this process a senior researcher will need to resolve differences and make final decisions.

2.7.1.3 Systematic review of studies to identify outcomes of importance to health service users

Similarly, it is necessary to systematically review the academic literature to identify Patient-reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and then extract patient-reported outcome domains. These come from existing PROMs often at the level of the individual questionnaire item [86]. This is recommended because the scale name used in PROMs and the scores attributed to the combined items are often found to be inconsistent. Therefore, analyses at a granular level are recommended [86]. The full process for this is described in Fig. 1 of the paper by Macefield et al. At this stage it is worth extracting details of the patient-reported outcome development and validity which will be helpful when selecting measures with which to assess the core outcomes.

A PRO long list extracted from PROMs may be supplemented with additional domains derived from a review of qualitative research studies if time allows (e.g. [87, 88]). It is recommended that interpretation of data from qualitative papers is guided by experts in the field.

2.7.2 Identifying and filling the gaps in existing knowledge

It is important to identify which key stakeholder groups’ views are not encompassed by systematic reviews of outcomes in published studies or the existing academic literature more generally, and decide whether these are gaps that need to be filled. An initial list from published clinical studies may be supplemented by undertaking qualitative research with key stakeholders whose views are important yet unlikely to be represented within systematic reviews of outcomes in previous studies. Where resources are limited, consultation with an advisory group whose membership reflects the key stakeholders may be used as an alternative to qualitative research, but it should be noted that such consultation is not qualitative research and the information arising from it does not have the same standing as the knowledge generated by research.

Qualitative interviews or focus groups with key stakeholders, especially patients, are recommended, particularly if the PROMS have lacked detailed patient participation in their development. The following section outlines in more detail how qualitative work may contribute to COS development. Nevertheless, it is recommended that qualitative research is guided by researchers with expertise in these. Interviews should be performed with a purposeful sample and use a semistructured interview schedule to elicit outcomes of importance to that population. The interview schedule may be informed by the domain list generated from the academic literature or be more informed by a grounded theory approach and start with very open questions. Interviews are audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed for content. The information can then be used to create new outcome domains or supplement the long list [89, 90].

2.7.3 Ontologies for grouping individual outcomes into outcome domains

Outcome domain models or frameworks exist to attempt to provide essential structure to the conceptualisation of domains [91], and have been used to classify outcomes that have been measured in clinical trials in particular conditions. Despite their intended use to provide a framework, there is not always consistency between the different models. In a review of Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) models, Bakas et al. found that there were wide variations in terminology for analogous HRQoL concepts [91]. Outcome hierarchies have been proposed for specific conditions [92] and cancer [93].

There have been several frameworks to classify health, disease and outcomes to date. There are various conceptual frameworks relevant to outcomes in health and these cover somewhat different areas of outcomes, some of which are described below.

2.7.3.1 Outcome-related frameworks

**World Health Organisation (WHO)**The WHO definition of health, although strictly a definition of health, can be considered a framework as it includes three broad health domains [[94](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR94 "WHO. WHO definition of Health. Geneva 1948. [cited 28 Apr 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\]: physical, mental and social wellbeing. This definition has not been amended since 1948 but is a useful starting place to study health. In a scoping review of conceptual frameworks, Idzerda et al. point out that although the three domains are clearly outlined, no further information about what should be included within each domain is provided \[[95](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR95 "Idzerda L, et al. Can we decide which outcomes should be measured in every clinical trial? A scoping review of the existing conceptual frameworks and processes to develop core outcome sets. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(5):986–93.")\].Patient-reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)

The PROMIS domain framework builds on the WHO definition of health to provide subordinate domains beneath the broad headings stated above [[41](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR41 "NIH. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–PROMIS. [cited 2015 28th April]. Available from: http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/domainframework

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\]: physical (symptoms and functions), mental (affect, behaviour and cognition) and social wellbeing (relationships and function). It was developed for adult and paediatric measures as a way of organising outcome measurement tools.World Health Organisation International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (WHO ICF)

The International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) offers a framework to describe functioning, disability and health in a range of conditions. The ICF focuses on the assessment of an individual’s functioning in day-to-day life. It provides a framework for body functions, activity levels and participation levels in basic areas and roles of social life; providing domains of biological, psychological, social and environmental aspects of functioning [96]. In many clinical areas, ICF core sets have been developed. These core sets identify the most relevant ICF domains for a particular health condition.

5Ds

5Ds is presented as a systematic structure for representation of patient outcomes and includes five ‘dimensions’: death, discomfort, disability, drug or therapeutic toxicity, and dollar cost [97]. This representation of patient outcome was developed specifically for rheumatic diseases, and the authors claim that each dimension represents a patient outcome directly related to patient welfare; for example, they describe how a patient with arthritis may want to be alive, free of pain, functioning normally, experiencing minimal side effects and be financially solvent. This framework assumes that outcomes are multidimensional, and it is critical that the ‘concept of outcome’ is orientated to patient values.

Wilson and Cleary

Wilson and Cleary [98] propose a taxonomy or classification for different measures of health outcome. They suggest that one problem with other models is the lack of specification about how outcomes interrelate. They divide outcomes into five levels: biological and physiological factors, symptoms, functioning, general health perceptions, and overall quality of life. In addition to classifying these outcome measures, they propose specific causal relationships between them that link traditional clinical outcomes to measures of health-related quality of life. For example, ‘Characteristics of the environment’ are related to ‘Social and psychological supports’ which in turn relates to ‘Overall quality of life’. Ferrans et al. [99] revised the Wilson and Cleary model to further clarify and develop individual and environmental factors.

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Filter 2.0

The OMERACT Filter 2.0 [31] is a conceptual framework that encompasses ‘the complete content of what is measurable in a trial’. That is, a conceptual framework of measurement of health conditions in the setting of interventions. It comprises three core areas: death, life impact and pathophysiological manifestations; it also comprises one strongly recommended, resource use. These core areas are then further categorised into core domains. They liken the areas to ‘large containers’ for the concepts of interests (domains and subdomains). They recommend that the ICF domains are also considered under life impact (ICF domains: activity and participation) and pathophysiological manifestations (ICF domains: body function and structure). Although OMERACT recommends the inclusion in a COS of at least one outcome reflecting each core area, empirical evidence is emerging that this is not always considered appropriate [48].

Outcome Measures Framework (OMF)

The Outcome Measures Framework (OMF) project was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) to create a conceptual framework for development of standard outcome measures used in patient registries [100]. The OMF has three top-level broad domains: characteristics, treatments and outcomes. There are six subcategories within the outcomes domain: survival, disease response, events of interest, patient/caregiver-reported outcomes, clinician-reported outcomes and health system utilisation. The model was designed so that it can be used to define outcome measures in a standard way across medical conditions. Gliklich et al. conclude that ‘as the availability of health care data grows, opportunities to measure outcomes and to use these data to support clinical research and drive process improvement will increase’.

Survey of Cochrane reviews

Rather than attempting to define outcome domains as others have done, Smith et al. performed a review of outcomes from Cochrane reviews to see whether there were similar outcomes across different disease categories, in an attempt to manage and organise data [101]. Fifteen categories of outcomes emerged as being prominent across Cochrane Review Groups and encompassed person-level outcomes, resource-based outcomes, and research/study-related outcomes. The 15 categories are: adverse events or effects (AE), mortality/survival, infection, pain, other physiological or clinical, psychosocial, quality of life, activities of daily living (ADL), medication, economic, hospital, operative, compliance (with treatment), withdrawal (from treatment or study) and satisfaction (patient, clinician, or other health care provider). The authors recognise that these 15 categories might collapse further.

2.7.3.2 Use of outcome-related frameworks in core outcome set studies

In the systematic reviews of COS [14, 39], 17 studies provided some detail about how outcomes were grouped or classified (Table 3).

Table 3 Methods for classifying/grouping outcomes (n = 17)

2.7.3.3 Use of outcomes recommended in core outcome sets to inform an outcome taxonomy

Based on the classification of outcomes in two previous cohorts of Cochrane systematic reviews [101, 102] and the outcomes recommended in 198 COS [14], the following taxonomy has been proposed:

- Mortality

- Includes subsets all, cause-specific, quality of death, etc.

- Physiological (or Pathophysiological)

- Disease activity (e.g. cancer recurrence, asthma exacerbation, includes ‘physical consequence of disease’, etc.)

- Blood pressure, laboratory values, recanalisation

- Infection

- New, recurrent

- Pain

- Quality of life

- Includes Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

- Mental health

- Psychosocial (includes behavioural)

- Function (or Functional status)

- Does this cover activities? Participation? (Read the Roberts and Counsell paper referenced in the review of stroke outcomes)

- Compliance with/withdrawal from treatment

- Satisfaction

- Reported by patient, health professional, etc.

- Resource use (or health resource utilisation)

- Includes subset hospital, community, additional treatment, etc.

- Adverse events (or side effects)

- Be clear that this could include things like death, pain, etc. when they are unanticipated harmful effects of an intervention

Pilot work is underway with selected Cochrane Review Groups to test the taxonomy for applicability. To date, one additional outcome domain, knowledge, has been identified as missing from the list.

2.7.4 Determining inclusion and wording of items to be considered in the initial round of the consensus exercise

It is important to spend time on this aspect of the process, in terms of the structure, content and wording of the list of items, to avoid imbalance in the granularity of item selection and description and ambiguity of language. Participants in the consensus process may identify such issues, necessitating revisions to the list during subsequent rounds [48]. A SAG (see ‘Achieve global consensus’ below) can provide valuable input at the design stage, prior to the start of the formal consensus process.

The review of existing knowledge, and research to fill gaps in that knowledge, has the potential to result in a long list of items. Consideration is needed regarding whether to retain the full list in the consensus exercise or whether to reduce the size of the list using explicit criteria. Preparatory work on how best to explain the importance of scoring all items on the list may help to improve levels of participation.

As noted in the section on qualitative research in COS development, because qualitative research involves patients and other stakeholders describing their views and experiences in their own terms, it gives COS developers access to the words, phrases and language that patients use to describe how conditions or interventions affect them. COS developers can, therefore, incorporate the words that patients use in interviews and focus groups to label and explain outcome items in a Delphi, thereby ensuring that the items are understandable and accessible for patients. Pilot or pretesting work involving cognitive or ‘think aloud’ interviews to examine how patients and other stakeholders interpret the draft items can help to refine the outcome labels and explanations [103, 104]. As the name suggests, this technique literally involves asking participants to think aloud as they work through the draft Delphi and provide a running commentary on what they are thinking as they read the items and consider their responses. This allows COS developers to understand the items from the perspective of participants. Cognitive interviews are widely used in questionnaire development to refine instruments and ensure they are understandable for the target groups.

Other methods previously used to determine the description of items include a reading-level assessment and amendment as necessary [55], and a review of terminology used in existing health frameworks such as ICF [96], PROMIS [[41](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR41 "NIH. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–PROMIS. [cited 2015 28th April]. Available from: http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/domainframework

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\], the Wilson and Cleary model \[[98](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR98 "Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65.")\] as well as related COS \[[48](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR48 "Chiarotto A, et al. Core outcome domains for clinical trials in non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(6):1127–42.")\].2.7.5 Short- or longer-term outcome assessment

One issue to consider is whether, and how, to address the timing of outcome assessment. Many COS developers have identified an agreed set of outcomes to measure, leaving the timing of assessment as an issue for trialists to decide subsequently depending on their particular context of use. In an alternative approach, in the COS for rheumatoid arthritis [26] agreed at a face-to-face meeting, it is recommended that radiological damage is only measured in trials where the patients are to be followed up for longer than 1 year. It is recommended that the approach to handling this issue be made clear to participants from the outset in the subsequent consensus process, to avoid ambiguity later on.

2.7.6 Eliciting views about important outcomes

Having identified a list of potential outcomes, the next step is to assess the level of importance given to each. Considerations concerning the choice of assessment method include the need to build a consensus with methodological rigor, and to adopt strategies to ensure that a diverse range of opinions is heard.

Methods used in previous studies to elicit opinions and to develop consensus about important outcomes include expert panel meetings (sometimes using nominal group technique (NGT) methods) and Delphi surveys. A single, heterogeneous consensus panel comprising the various stakeholders may be deemed appropriate for particular areas of health care whereas separate panels for different stakeholder groups followed by work to integrate the multiple perspectives may be more appropriate for others.

If participants in a consensus process are shown a list of potential outcomes, we recommend that in general they should be given the opportunity to propose the inclusion of additional items, especially as the academic literature may not include outcomes associated with the most recent treatments available or the most pressing current concerns for stakeholders.

We consider a Delphi exercise to be a useful way of gaining information about opinion from a wide group of participants. Of 127 ongoing COS in the COMET database (as of 12 April 2016), 108 (85%) involve a Delphi survey, and hence we discuss this method in more detail below.

2.7.6.1 The Delphi technique

With the exception of the Delphi technique, all other methods for COS development described earlier involve face-to-face communication. The Delphi technique is advantageous in that it is anonymous, avoiding the effect of dominant individuals, and can be circulated to large numbers with wide geographic dispersion.

The Delphi technique was originally developed by Dalkey and Helmer (1963) at the Rand Corporation in the 1950s [[105](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR105 "RAND Corporation. Delphi Method. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.rand.org/topics/delphi-method.html

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\]. In a COS framework, the method is used for achieving convergence of opinion from experts (stakeholders) on the importance of different outcomes in sequential questionnaires (or rounds) sent either by post or electronically. Responses for each outcome are summarised and fed back anonymously within the subsequent questionnaire. Participants are able to consider the views of others before re-rating each item and can, therefore, change their initial responses based on the feedback from the previous rounds. With no direct communication between participants this feedback provides a mechanism for reconciling different opinions of stakeholders and is, therefore, critical to achieving consensus.There remains, however, uncertainty as to the optimum way to use such methodology. Many issues need to be considered at the outset, all of which may have an impact on the final results. These include:

- Number of panels

- Group size

- Participant information

- Number of rounds

- Structure of the questionnaires

- Methods of scoring

- Nature of feedback presented between rounds

- Criteria for retaining outcomes between rounds

- Attrition (response bias) between rounds

- Consensus definitions

- How the degree of consensus will be assessed

In the following sections, we discuss each of the above issues in detail and offer guidance on different approaches.

Single or multiple panels for different stakeholders

The choice of stakeholder groups to be involved in the development of a COS has been discussed in ‘Stakeholder involvement’ in Chapter 2 above. There may be additional considerations regarding which groups should be involved in a Delphi survey. For example, in a COS for early stage dementia, interviews rather than Delphi survey participation may be considered to be the more appropriate way to include patient views.

What also requires consideration is how best to combine the views of different stakeholders within a Delphi survey. The issue of the impact of panel composition on Delphi performance has seldom been investigated in general [106]. Some COS studies have used a single panel of experts from one particular stakeholder group or combined a heterogeneous group of participants, representing multiple stakeholder groups, into a single panel (that is, ignoring stakeholder status when generating feedback and assessing consensus). Others have used multiple homogenous panels, each formed by a different stakeholder group. In rheumatology, Ruperto et al. [54] used a single panel of paediatric rheumatologists whilst developing a COS in systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE) and juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), whilst Taylor et al. [107] combined the views of rheumatologists and industry representatives into a single panel in the development of a COS in chronic gout. The MOMENT study (Management of Otitis Media with Effusion in Cleft Palate) considered eight separate stakeholder groups and treated them as multiple separate panels [55].

The single homogeneous panel approach will result in core outcomes deemed essential by only one stakeholder group. If a single panel is formed by combining heterogeneous stakeholder groups (such that feedback and criteria for consensus are based on the group overall and ignore stakeholder type), careful consideration and justification is needed of the panel mix. If the data are simply amalgamated with no consideration of the separate stakeholder groups, the resulting set may depend on the relative proportions of stakeholders participating or on weightings that may be used for different groups. As an example of imbalance in stakeholder representation, the Taylor et al. study [107] had only three industry representatives and the remaining 26 respondents were rheumatologists. The single-panel approach here is clearly in favour of the rheumatologists’ opinions.

In areas where differing stakeholder opinions are expected, a better approach would be to consider multiple panels, retaining distinct stakeholder groups when generating feedback and considering criteria for consensus (see later sections). The final core set, or outcomes taken forward to the next stage of COS development, may then consist of (1) outcomes deemed essential by all stakeholder groups or (2) outcomes deemed essential by any stakeholder group. The former option may, therefore, result in the most important outcomes for any particular group being excluded from the core set which may not be acceptable. At the same time, whilst including items deemed essential by any relevant stakeholder group ensures that outcomes essential to any group are included, the resulting set may be too extensive to be practical and it could be argued that in this scenario consensus has not been achieved since there will be items that not all groups agreed on. Alternative approaches will be described in a later section on defining consensus (see ‘Defining consensus’ below).

Group size

The decision regarding how many individuals to include in a Delphi process is not based on statistical power and is often a pragmatic choice. For example, the group size may be dependent on the number of experts or patients available within the scope of the COS being developed. These numbers may be particularly small if the condition is rare or the intervention of interest is not widely used. In their international Delphi study, Smith and Betts (2014) included only 12 acupuncturists working in pregnancy with at least 5 years’ experience in traditional Chinese medical techniques [108]. As a contrast, Ruperto et al. (2003) enrolled 174 paediatric rheumatologists from two professional organisations in an international Delphi survey [54]. Blazeby et al. (2015) recruited 185 patients and 126 consultants and specialist nurses in a UK-based study to identify a COS for surgery for oesophageal cancer [58], whilst van’t Hooft et al. (2015) involved 32 parents and 163 health professionals in an international Delphi survey as part of the development of a COS for the prevention of preterm birth [57].

Consideration should be given to the number of participants that are invited into the Delphi (allowing for attrition between rounds; see later). Dependent on the consensus definition, the results may be particularly sensitive with smaller numbers of participants. When potential numbers are small, stakeholder group members could be pooled, particularly if it is expected that opinions are unlikely to differ. Typically, such a decision should be done in consultation with the Steering Advisory Group to ensure the appropriateness of the grouping, and without knowledge of the results. Any revisions to the Delphi protocol should be documented with reason.

The key consideration with group size is that there should be good representation from key stakeholder groups with qualified experts who have a deep understanding of the issues. The more participants representing each stakeholder group the better, both in terms of the COS being generalisable to future patients and in convincing other stakeholders of its value.

Participant information

It is important for all participants to be fully aware of the purpose of the Delphi survey and what will be expected of them. This is crucial both in terms of enabling informed consent and equipping participants to be able to prioritise and score outcomes. The notion of a COS and even an outcome may not be clear to all. Participant Information Sheets may need to use different terminology for different stakeholder groups and should be piloted in advance. Plain language summaries for patients and carers, including a description of an outcome, a COS and a Delphi survey, are available on the COMET Initiative website [[109](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR109 "COMET. Plain Language Summary. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org/resources/PlainLanguageSummary

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].It is also advisable to ensure that the instructions provided within each round of the Delphi survey reiterate the overall aim of achieving consensus of a core set of outcomes.

Number of rounds

A Delphi survey must consider at least two rounds (that is, at least one round of feedback) to be considered a Delphi survey. The number of Delphi rounds varies across different COS development studies. Typically, COS studies contain two [56, 58, 60, 110] or three rounds [55, 107, 111]. One study reported six rounds [112]; however, this included several rounds of open-ended questions to generate debate in controversial areas in the field of infant spasms and West syndrome. Open-ended rounds may also be used to generate an initial list of outcomes prior to any outcome scoring [60, 113, 114], as an alternative to reviewing the academic literature for example.

Rather than pre-determining the number of rounds, the process can be dynamic with subsequent rounds incorporated if further prioritisation is warranted. Whilst we would not expect, nor require, consensus to be reached on all outcomes in the Delphi questionnaire, it is necessary that a reduced number of outcomes has been agreed (in terms of prespecified criteria) to be of most importance, in order to inform the COS. Outside COS development work, Custer et al. (1999) have recommended that three iterations are sufficient to collect the relevant information to reach a consensus in most cases [115].

From a practical perspective, the number of rounds may also be limited by time, cost or consideration of the burden on participants completing multiple rounds of Delphi. The time taken for participants to complete a round of Delphi is highly variable and will often depend on the number of outcomes being scored. It is advisable to pilot the questionnaires beforehand to ensure that it is practical. Typically, each round of Delphi will remain open for about 2 or 3 weeks, although latter rounds may be kept open longer if response rates are low to try to minimise the potential for attrition bias (see later). Following the closure of a Delphi round, an additional 2 or 3 weeks is required to analyse the data and set up the next round, although this will depend on the design and can be much shorter if using software developed specifically for online Delphi surveys; for example, the DelphiManager software developed by COMET [[116](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR116 "COMET. DelphiManager. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org/delphimanager/

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].Structure of the questionnaires

Careful consideration is needed when designing the Delphi questionnaire, as for any questionnaire. For example, outside of COS development Moser and Kalton [117] recommend that jargon and technical terms should be avoided in questionnaires; anecdotal evidence from the piloting of Delphi questionnaires for core sets for cancer surgery and OME with cleft palate suggest that lay terms are preferred to technical medical terms, even by health professionals. Stakeholder involvement in the design and piloting of the Delphi questionnaire is recommended to ensure that it is accessible, comprehensible and valid.

Order of questionnaire items

Previous research, outside of COS development, has demonstrated that the order in which questions are presented in a questionnaire could affect response rates and actual responses to question items [118]. The idea of the ‘consistency effect’, where items are answered in relation to responses to earlier items, has been researched for more than 50 years with recommendations that general questions should precede specific ones [119], and questions should be grouped into topics [120]. It has also been suggested that if there is evidence that respondents have stronger opinions on some items than others these should be placed first [118]. It has been argued that order effects will be greater for interview surveys and minimal for written surveys since participants have longer to respond to items and have the opportunity to look at all items before responding [121], but effects have been observed in written surveys [122].

Within the development of a COS we are only aware of one published abstract reporting the effects of question order. For surgery for oesophageal cancer recent methodological research considered the impact of the ordering of patient-reported and clinical outcomes in the Delphi survey. Participants were randomly allocated to receive a questionnaire with the patient-reported outcomes presented first and the clinical outcomes last, or vice versa. The study found that ordering of outcomes in a Delphi questionnaire may impact on both response rates and actual responses, hence subsequently impacting on the final core set [123]. Further research is needed to better understand potential order effects in the context of COS development. We are aware of an ongoing nested study in which participants are randomised to one of four orderings of the outcomes throughout the Delphi survey [[124](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR124 "Needham DM. Improving long-term outcomes research for acute respiratory failure [cited 2016 March]. Available from: www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/360

. Accessed 30 May 2017.")\].Additional open questions

As described previously, there are different methods of identifying an initial long list of outcomes to inform the Delphi survey. Whatever method is employed the initial list may not be entirely exhaustive and there may be added value in including an open question in the round-1 questionnaire to identify additional outcomes. This open question could be placed at the beginning or the end of the questionnaire depending on the intended purpose.

If placed at the beginning of the questionnaire participants might be asked to identify a small number of outcomes that are of most importance to them before they see the outcomes included in the questionnaire. If placed at the end, participants might be asked to list any additional items that they do not feel have been considered in the questionnaire. The former approach will help to ensure that there are no key outcomes that have been omitted, whilst the latter approach will help to ensure that a more exhaustive list of outcomes. Whether included at the beginning or end of the questionnaire, criteria for including additional items in round 2 should be specified in a protocol; for example, any new outcome suggested may be included, alternatively only those new outcomes suggested by two or more respondents might be added.

Scoring system

Core outcome set studies have used a variety of different scoring systems to rate outcomes within a Delphi process, although the majority involve a Likert scale. Other methods include the ranking of outcomes [54, 114] and allocation of points (for example, division of 100 points across all outcomes) [110, 114, 125]. The 9-point Likert scoring system where outcomes are graded in accordance to their level of importance is a common method. Typically, 1 to 3 signifies an outcome is of limited importance, 4 to 6 important but not critical, and 7 to 9 critical [55, 126, 127]. This framework is recommended by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group for assessing the level of importance about research evidence [21, [128](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR128 "GRADE. GRADE working group. [cited 2016 April]. Available from: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org

. Accessed 30 May 2017. ")\]. Others have used similar 9-point systems. For example Potter et al. \[[56](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR56 "Potter S, et al. Development of a core outcome set for research and audit studies in reconstructive breast surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102(11):1360–71.")\] and Blazeby et al. \[[58](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR58 "Blazeby JM, et al. Core information set for oesophageal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102(8):936–43.")\] asked participants to rate the importance of each outcome on a 1–9 scale where 1 was ‘not essential’ and 9 was ‘absolutely essential’. Some studies have also included an ‘unable to score’ category to allow for the fact that some stakeholder group members may not have the level of expertise to score certain outcomes. As an example, in the development of a COS for otitis media with effusion in children with cleft palate, some of the participants from the speech and language therapist stakeholder group chose not to score some of the outcomes related to the more clinical aspects of the condition \[[55](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR55 "Harman NL, et al. The importance of integration of stakeholder views in core outcome set development: otitis media with effusion in children with cleft palate. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129514.")\]. Other studies have used four- \[[129](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR129 "Broder MS, et al. An agenda for research into uterine artery embolization: results of an expert panel conference. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(4):509–15.")\], five- \[[111](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR111 "Smaïl-Faugeron V, et al. Development of a core set of outcomes for randomized controlled trials with multiple outcomes—Example of pulp treatments of primary teeth for extensive decay in children. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e51908.")\] and seven- \[[107](/article/10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4#ref-CR107 "Taylor WJ, et al. A modified Delphi exercise to determine the extent of consensus with OMERACT outcome domains for studies of acute and chronic gout. [Erratum appears in Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Nov;67(11):1652. Note: Mellado, J Vazquez [corrected to Vazquez-Mellado, J]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(6):888–91.")\] point Likert scales to score outcomes.Feedback between rounds

In order to increase the degree of consensus amongst participants, differing views need to be reconciled. The mechanism for this within a Delphi process is the feedback presented to participants in subsequent rounds, enabling different opinions to be considered before re-rating an outcome. At the end of each round the results for each outcome are aggregated across participants and descriptive statistics presented (see later in this section). Participants can be encouraged to provide a reason for their scores on individual outcomes, which can be summarised as part of the feedback.

The generation of these descriptive statistics will depend on whether a single panel or multiple panels have been used. In a single-panel study, feedback ignores any distinct stakeholder groups and summarises and presents scores for each outcome for all participants involved, hence hiding any disparate views between stakeholders. As described earlier, if there are disparate views the final COS will depend on the relative proportions of stakeholders. Calculation of summary scores could of course be weighted by stakeholder group, but it is difficult to ascertain what weightings should be given and there is no current guidance on this. In addition, recent evidence in the development of COS suggests that patients are more likely than health professionals to rate an outcome as essential; three studies found that the average score awarded to outcomes in the round-1 questionnaire was greater for patients than health professionals [130], so even in a study involving equal numbers of patients and health professionals, patients may be more likely to influence a core set if outcome scores are simply combined across stakeholder groups.

In a multiple panel study there are three possible approaches to providing feedback. Participants might receive an overall average across all stakeholder groups; however, this would be analogous with the single-panel approach. Alternatively, participants could receive feedback from their own stakeholder group only or from all stakeholder groups separately. If participants receive feedback from their own stakeholder group only, whilst this may enable consensus within stakeholder groups, it provides no opportunity for consensus across groups. Ongoing COS projects include nested randomised studies comparing these three approaches [131, 132].

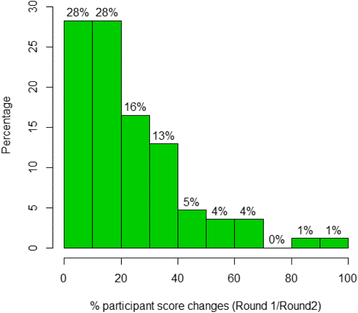

Recent methodological work, including a before/after study [55] and nested randomised trials [130], examined the impact of providing feedback from all stakeholder groups separately compared to feedback from the participant’s own group only. Type of feedback presented did impact on the subsequent scoring of items [55, 130] and the items subsequently retained at the end of the Delphi process [130]. The research also demonstrated that providing feedback to participants from both stakeholder groups improved consensus between stakeholder groups in terms of reduced variability in responses and improved agreement in items to retain at the end of the Delphi process [130].

In some ongoing COS studies, participants are being asked for the reasons that they have changed scores between rounds particularly if the change in score is from critically important to a score of less importance or vice versa [133, 134]. This will enable us to better understand the impact of feedback and help optimise the Delphi.

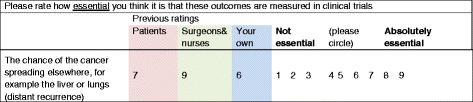

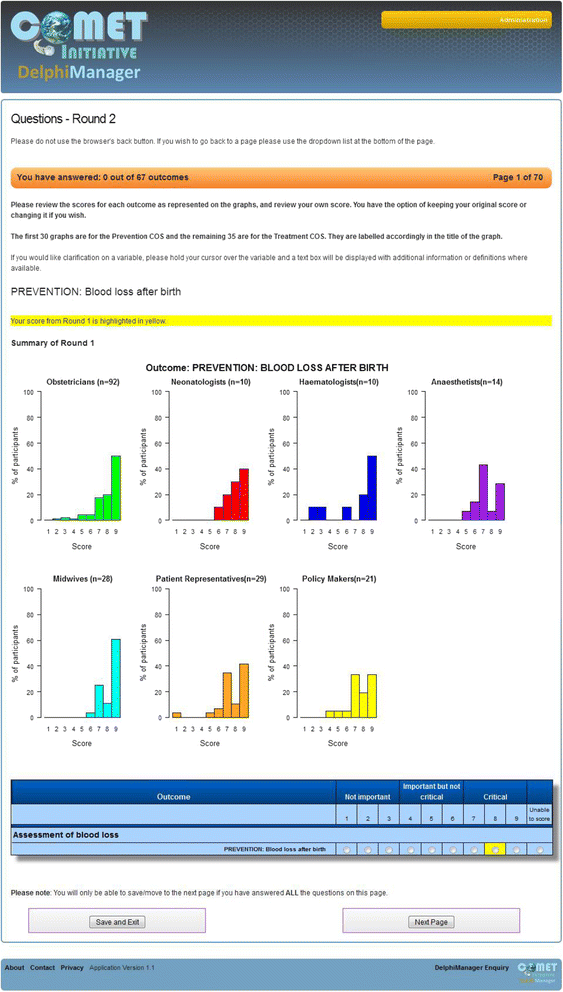

There are a number of ways that feedback can be presented. A summary statistic, such as a median or mean (if normally distributed), may be presented for each outcome [58]. Figure 2 demonstrates how feedback was presented in round 2 of a Delphi postal survey used within the development of a COS for surgery for colorectal cancer. Mean scores (rounded to the nearest integer) were presented for both stakeholder groups (patients and surgeons/nurses) included in the study. The participant’s individual score from round 1 is also presented. Single summary statistics are sometimes also presented with a measure of dispersion such as a standard deviation, interquartile range, range or other percentiles [107, 126, 127]. Alternatively, the percentage scoring above a prespecified threshold (for example, 7–9 on a 9-point Likert scale) may be presented [56]; or, the full distribution of scores may be provided graphically. Figure 3 provides a screenshot of an electronic round-2 Delphi questionnaire created within DelphiManager. In this instance a histogram of round-1 scores is presented for each stakeholder group. The participant’s round-1 score is this time highlighted in yellow.

Fig. 2

An outcome from a round-2 questionnaire for surgery for colorectal cancer presenting the mean score for round-1 for patients and health professionals separately

Fig. 3

An outcome from a round-2 questionnaire presenting the percentage distribution of scores across all stakeholder groups with options for participants to review their previous round score and re-score (taken from DelphiManager)

Further research is required to determine which presentation method is most useful and easily interpreted by participants; however, the optimum approach may differ depending on the setting and stakeholder groups involved. Preparatory work with a small group of participant representatives to ensure that the feedback is understood is advisable.

Retaining or dropping items between rounds

After the initial Delphi round, subsequent rounds might retain all outcomes [55, 57, 125], or some items may be dropped according to prespecified criteria [56, 58]. Whilst there are examples of both approaches in the academic literature, at present there is no empirical evidence of whether the decision impacts on the final core set. Retaining all items for all rounds may provide a more holistic approach, enabling participants to score and prioritise the list of outcomes as a whole. If items are dropped between rounds there may be items considered of most importance to some participants which are not present in later rounds and this may hinder their ability to prioritise the remaining items. This may be particularly pertinent when scoring systems require participants to allocate a certain number of points across all outcomes [125]. In addition, if items are dropped after the first round, participants will not get the opportunity to re-score those outcomes taking into account feedback on scores from other participants. Suppose that a particular outcome is rated highly by patients in round 1 but poorly by other stakeholder groups and that based on prespecified criteria the outcome is dropped. It is plausible that had participants seen that patients rated the outcome highly, other stakeholders would have increased their scores such that the outcome would have been retained at the end of round 2.

At the same time, if the initial list of outcomes is large, including them in each Delphi round may impose sufficient burden on participants to increase attrition from one round to another. If the decision is made to reduce the number of items from one round to the next, more inclusive criteria for retaining items in earlier rounds may be sensible. For example, in the recent development of a COS for surgery for oesophageal cancer, 67 outcomes were included in round 1. Criteria for inclusion in round 2 were that an item be rated 7 to 9 (on a 9-point Likert scale) by 50% or more participants and 1 to 3 by no more than 15% of participants in at least one stakeholder group [58]. Items were retained at the end of round 2 using stricter cut-off criteria; retained items were rated between 7 and 9 by over 70% of respondents and 1 to 3 by less than 15% by at least one stakeholder group. Using less stringent criteria in earlier rounds, and retaining items for which these criteria are met for any single stakeholder group, reduces the likelihood of dropping outcomes that may have been rated more highly in subsequent rounds had participants been given feedback on them.

In the absence of any empirical evidence to inform the optimum approach, the decision may be largely led by the initial number of outcomes. An intermediate approach, which may to some extent address the disadvantages of both methods, would be to retain all items between rounds 1 and 2, hence enabling participants to re-score in light of feedback for every item, and then drop items in subsequent rounds. Whatever design used, if any items are to be dropped from one round to the next, criteria need to be clearly defined in a protocol.

Attrition and attrition bias

The degree of non-response after the first round of the Delphi (attrition) may be highly variable between studies and may be dependent on the timing of Delphi rounds (for example, holiday season may increase attrition), the length of the Delphi (from previous knowledge of completing the previous round), the time elapsed between the first and final round (health care professionals may leave the service, or participants may become disinterested), and the method of recruitment of participants, as well as many other factors. For example, Bennett et al. (2012) observed 0% attrition in their small Delphi study (fewer than 10 participants) but their recruitment strategy was a targeted approach to known experts [126], whereas Smith and Betts (2014) observed higher attrition rates (17%) from 12 participants from inviting trial authors from the relevant academic literature [108]. Similar attrition rates to Smith and Betts were seen in a much larger study for oesophageal cancer surgery which recruited 126 surgeons and nurses identified through a meeting of the Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, and by personal knowledge of surgeons, and 185 patients recruited from three clinical centres. Attrition rates between rounds 1 and 2 were 15% for professionals and 17% for patients.

If attrition rates are thought to be too high, either overall or for a particular stakeholder group, then strategies should be adopted to increase the response rates. Personalised reminder emails to participants (with details of current response rates), personalised emails from distinguished researchers in the field, direct telephone calls, and the offer of being acknowledged in the study publication have all been found to be helpful strategies in increasing response rates. Consideration should be given to keeping Delphi rounds open longer if it is thought that this may increase response rates. Whilst there is no guidance on what constitutes an acceptable response rate, typically around 80% for each stakeholder group would be deemed satisfactory in most situations.

Attrition bias will occur when the participants that do not respond in subsequent rounds have different views from their stakeholder group peers who continue to participate. For example, if the feedback a participant receives suggests that they are in a minority with regard to their scoring of importance about particular outcomes, then they may be more likely to drop out, leading to over-estimation of the degree of consensus in the final results [135].

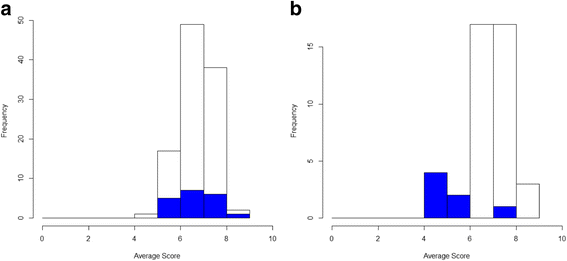

Only one study to date has examined whether attrition bias is present between Delphi rounds in a COS project [55] although many ongoing COS studies are now planning to consider this. In the Harman et al. study (2015), average round-1 scores were calculated for each participant then plotted according to whether participants completed round 2 or not. Figure 4 provides two hypothetical scenarios representing the responses from two different stakeholder groups. In stakeholder group A, we can see that the average scores for those completing only round-1 (blue bars) are well contained within those average scores of those completing round 1 and round 2 (white bars). On average, participants staying in have scored outcomes similarly to those leaving the study, suggesting that attrition bias is unlikely to affect the results. For stakeholder group B, we can see that the average round-1 scores of those who did not complete round 2 are lower. If too many participants drop out of the Delphi process with lower previous round scores than the majority opinion, this will overestimate the level of importance of outcomes and over-inflate the degree of consensus.

Fig. 4

Average scores in round 1 across all outcomes for (a) stakeholder group 1 and (b) stakeholder group 2. Shaded bars represent those who provided scores in round 1 only; open bars represent those scoring in both rounds 1 and 2

Inevitably, examining average scores between completers and non-completers has its limitations. For example, non-completers may score some outcomes much higher than completers and score other outcomes much lower than completers, but average scores may remain similar between the two groups. Another approach to examine potential attrition bias would be to look at average scores of individual outcomes amongst those who do and not complete later rounds. If formally comparing average scores through statistical hypotheses tests it should be remembered that there will be an issue of multiple significance testing and false positive findings. However, such testing may enable identification of obvious patterns or differences in scoring between the non-completers and completers; for example, if non-completers are scoring patient-reported outcomes more highly than clinical outcomes but the reverse is seen for completers.

COS developers should consider the potential nature and cause of likely attrition bias when deciding how best to examine its presence. The assessment of attrition bias should be repeated for further rounds of the Delphi, that is, average round-2 scores should be compared for those completing round 3 and those dropping out after round 2.

Defining consensus