Restoring Daniel Burnham's vision for Chicago's lakefront gateway (original) (raw)

"I suppose he thinks we are going to hog it all!" - architect John Wellborn Root, after being snubbed by a colleague suspecting Root and Daniel Burnham were going to monopolize the design of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

"We don't want nobody that nobody sent." - Chicago ward commiteeman responding to a young Abner Mikva's offering his time to work for the campaigns of Adlai Stevenson and Paul Douglas.

Lector, si monumentum requiris, Circumspice. Has anyone better personified Christopher Wren's famous epitaph than Daniel Burnham?

But circumspice, my eye: we're going to build him one, anyway.

How that whole tale is playing out - along with the evolution of two other temporary structures being constructed this summer - may offer up a decidedly unofficial, but far truer, less sentimentalized reconsideration of Burnham's 1909 Plan of Chicago, whose centennial celebration this year is what's cooked up the whole porridge.

reconsideration of Burnham's 1909 Plan of Chicago, whose centennial celebration this year is what's cooked up the whole porridge.

In February, the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects sent out a press release announcing that twenty architects had been invited to submit proposals in a competition for the design of a memorial to Daniel Burnham on a site in front of the Field museum. Nowhere in the release was there indication of who decided on these firms, or why. Nor was there indication who would be winnowing the entries down to the three to five finalists that would be submitted to a blue-ribbon jury to decide a final winner.

David Goodman, current co-president of the Chicago Architectural Club, decided he  was mad as hell and he wasn't going to take it any more. On March 12, little more than a week before the March 20th deadline for submissions, he launched a frontal assault on what he saw as the closed, inbred nature of the competition to design the Burnham Memorial, inciting his excluded colleagues to "Crash the Burnham Memorial Competition."

was mad as hell and he wasn't going to take it any more. On March 12, little more than a week before the March 20th deadline for submissions, he launched a frontal assault on what he saw as the closed, inbred nature of the competition to design the Burnham Memorial, inciting his excluded colleagues to "Crash the Burnham Memorial Competition."

"An opportunity like the Burnham Memorial Competition ought to be open to more than just the usual suspects," Goodman wrote. "So…having gotten our hands on the competition documents through means I won’t disclose, we’ve sent the entire thing out to the club . . . this ought to be a moment for the architectural community to begin to put pressure on the PBC, Park District, whomever, to open up a process for public  competitions for public work."

competitions for public work."

"I have lived and worked for many years in Spain, where law dictates that all public projects must be awarded through an open competition process. The result: nearly three decades of consistently excellent work, work that has given emerging architects (like Rafael Moneo, in his time, Enric Miralles and Carme Pinos, Mansilla and Tunon, etc) a chance to raise their profiles, and to raise the overall relevance of architecture – the results of these competitions end up in the news, in the public consciousness. The competition process also ends up forcing established architects to compete for work. In the end, the competition system produces better work, through more transparent means."

The official twenty - each of whom will receive $5,000 for their troubles - is a who's-who of prominent Chicago firms, from SOM and OWP/P, to Perkins+Will, Studio Gang, David Woodhouse, John Ronan, etc., and Goodman was quick to admit "many of the architects chosen are really good."

In a comment posted to Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin's report on the rebellion, AIA Chicago EVP Zurich Eposito expressed surprise at Goodman's campaign, claiming he had talked to Goodman earlier in the week about the possibility of unsolicited entries, and that "I confirmed with our committee, board, and funders and all of us unanimously agreed that it was a great idea. We are also planning a publication and exhibit of all the submissions, including the mavericks."

Why, if it was such a good idea, it had occurred to no one involved in the competition until Goodman's prodding was left unexplained. One report said instructions for submitting entries via FTP were sent to the official competitors last week with stern admonitions not to share the information with any of the unwashed uninvited.

Goodman wrote me from New Orleans on last Thursday to report that he and the CAC's other co-president, Romina Canna, have a meeting set up with Esposito this week to drop off the entries they've collected. AIA Chicago now has a page up on their website soliciting ideas for the memorial from all comers, complete with instructions and an address for submissions, and an extended deadline of 10:00 p.m., Monday, March 30th.

Serpentine Gallery, Toyo Ito and Cecil Balmond, architects. Photograph: Louisiana Museum, Denmark

|

|---|

The developing controversy could actually be said to have begun with the announcement last June by the Burnham Plan Centennial Committee that architects Zaha Hadid and UNStudio's Ben van Berkel had been chosen to design two temporary pavilions for Millennium Park "to stimulate thinking about the future, including video representations of the visions of some of Chicago’s leading architects and urban designers." At a lecture last week on Burnham by Kristen Schaffer, Art Institute Architecture and Design curator Joseph Rosa referred to the projects as Chicago's versions of London's Serpentine Gallery, where the design of a temporary park structure each year by a different world renowned architect, from Hadid, to Oscar Niemeyer, Frank Gehry (last year), and Toyo Ito and Cecil Balmond, has resulted in some of the most arresting buildings of the last decade.

Serpentine Gallery, 2007, London, Zaha Hadid, architect

|

|---|

Nowhere in the press release, however, was there any discussion of how, why, and by whom these two architects were chosen. Were they the most suitable to the project? The most interested? The only available? Wouldn't it have been more interesting to have one pavilion from an international architect contrasting with a design from a Chicago architect?

Although the scheduled unveiling date is less than three months away, we still have no idea what we're getting. (Maybe we can nab Zaha's snail spaceship Mobile Art pavilion, now that sponsor Chanel has cancelled the rest of its worldwide tour.) Also still unknown is whether, in the wake of the new monasticism that's infected architecture critics after last fall's economic meltdown like witchcraft spooked Salem, we will find Hadid and van Berkel besieged on the Chase Promenade this summer by black robed penitents holding crosses and chanting in eerie unison, "stararchitects . . . unclean, unclean."

Are competitions and Chicago architecture an oxymoron? Read on.

Is There a Disconnect between Competitions and Chicago Architecture?

reporter Jackson Bentley: I know you've been given no artillery.

Prince Feisal: That is so.

Bentley: You're handicapped.

Feisal: It restricts us to small things.

Bentley: It's intended to.

- Michael Wilson and Robert Bolt, Lawrence of Arabia

Truth be told, the IIT competition that brought Rem Koolhaas to Chicago notwithstanding, architectural competitions are to Chicago architecture are like parallel lines extending to infinity: they don't converge.

In 2001, the city invited eight architectural firms to participate in a competition for the redesign of Chicago's Randolph Street visitors center. The result was a series of creative and competitive designs, none of which were ever built.

Five years ago this coming April, Studio Gang Architects won a hotly contested competition to design a visitors center for the new Ford Calumet Environmental nature center, on land reclaimed from former industrial property on Chicago's far south side. It was announced at the time the project was fully-funded, and that "The FCEC is scheduled to open in 2006." To the best of my knowledge, not a spade of earth has yet to be turned.

The Chicago Architectural Club, itself, played the mayor's patsy in yet another instance of the traditional scam. The CAC thought it had scored a coup in reaching an agreement to work with the city on the club's 2005 Chicago Prize competition. “It really started,” said CAC's Brian Vitale at the time, “with a call that I made with my co-president Robert Benson to the mayor's office to see if there any architectural issues that were needing to be dealt with in the city that we could lend a hand with."

And what topic did the mayor select to take advantage of this priceless opportunity to get thousands of hours of free work from architects? Newer, better ideas for the replacements to the CHA high-rises then being demolished? Using superior design to help resurrect decaying neighborhoods? Redeveloping abandoned railyards? Rescuing the streets from the derelict gloom of the Loop L? No, no, no . . . and no.

Water tanks. That's what the mayor came up with. Those quaint, vanishing dinosaurs of the age before powerful pumps, out of sight, out of mind.

Still, not wanting to be churlish, architects did expend thousands of valuable hours - remember, this was a time when there was still a lot of paid work to go round - submitting over 200 entries of often astonishing commitment, creativity and quality. The mayor stopped by the Cultural Center to congratulate competition winner Rahman Polk, and to walk through an exhibition of many of the best entries. Then he left, taking the photographers and reporters with him. And nothing was heard of it ever again. I guess it's the thought that counts.

Toss those pesky would-be volunteers a bauble to keep them occupied while the real work is done by reliable people, behind closed doors. That's the Chicago way.

So now we're having a competition for a memorial to Daniel Burnham. A diversionary sideshow, to be sure, but not without its challenges. The official illustration for the  competition makes the site appear to be part of a broad expanse of largely flat lawn in front of the Field Museum. In fact, it's a large marshmallowy lump of earth raking down from the raised level of the museum to the walkways lowered to pass under nearby streets.

competition makes the site appear to be part of a broad expanse of largely flat lawn in front of the Field Museum. In fact, it's a large marshmallowy lump of earth raking down from the raised level of the museum to the walkways lowered to pass under nearby streets.

Unlike its neighbors, the Shedd Aquarium and Adler Planetarium, there is no direct axial approach to the Field Museum, even though its the dominant building on the campus. You have to approach it, crab-like, from the sides. While this processional is not without visual interest, the lack of a direct axial access means that the full majesty of the Field's facade and grand classical entrance wing remains obscured behind the surging hill in front of it.

The bottom line, however, is that this competition doesn't seem to be about much of anything. It solves no major problem, addresses no pressing challenge. It reeks of safety and inconsequence: Water Tanks, 2009 edition.

The site, itself offers up a a kind of bastard commentary, at a Field Museum that's far removed from Burnham's original placement for it at the current location of Buckingham Fountain, where it was to serve as the great cultural gateway between the lakefront and Burnham's magnificent new boulevard to the west, its vista dominated by the soaring dome of a civic center whose urbane beauty was engineered to make Parisians weep with envy.

And therein lies a truly worthy subject for a competition. Read on.

Restoring Burnham's Vision for a Grand Gateway to the Lake

It was in that great civic center that Daniel Burnham, in his 1909 Plan, sought to give Chicago a new heart, one that would replace the bloody slaughterhouses, the coal-blackened precincts of industry, the dark canyons of densely packed skyscrapers, as the dominant image of the city, replacing it with a fresh vision of a city reborn in light, nature and classical grace, carried out through broad, diagonal avenues into the expanding city in widening concentric, Swedenborgian circles of enlightenment.

And he would carry Congress Street, newly minted as a broad tree-lined boulevard, eastward, a flowing river of beauty, impervious to contamination as it passed through the dark old central business district, into a sweeping plaza and park, anchored by the palatial splendor of the Field Museum, to arrive, at last, at a magnificent harbor and the inexhaustible majesty of Lake Michigan.

So much for plans.

What actually transpired, however, was an obscene parody of Burnham's vision. It was the mid-1950's, less than a decade after the triumph of World War II. The economy was robust. The future looked bright, and it would be bright, but not for the big center cities, which were about to be thrown into crisis.

The Interstate Highway Act meant an easy source of big money for the kind of huge public works projects - with jobs and contracts and places for cutting ribbons and taking pictures - that politicians loved. Armies of workers were recruited to build the bold new, limited access expressways, which sliced up neighborhoods, demolished hundreds of blocks of homes, shops and factories, and dislocated thousands.

To the city fathers, it was a small price to pay to secure Chicago's future, but it proved a Faustian bargain. For the center cities, the gleaming new highways with their manicured lawns brought, not prosperity, but ruin. They functioned as a giant vacuum sucking out much of the city's white middle-class. For those families, fearing their old neighborhoods being overtaken by poor blacks, the expressways were the escape valve to a new normalcy - clean, fresh and secure.

Where Burnham had envisioned a great new civic center, planners knotted the arteries of three superhighways into a four block square, brutal interchange that ripped the urban fabric to shreds. The way its ramps intertwined earned it the nickname, "the Spaghetti Bowl." The new Congress Expressway poured through a small opening at the base of the fortress-like, two block square, 14 story high post office, constructed in 1932 just west of the river..

Congress Street, Burnham's grand boulevard, became, in essence, a feeder ramp for the expressway, with racing traffic that forced itself even onto former sidewalks, replaced with new pedestrian walkways ripped out the interiors of the buildings lining the street, mutilating classic buildings at will, including the destruction of the beautiful Oak Bar of Adler & Sullivan's 1888 Auditorium Building.

new pedestrian walkways ripped out the interiors of the buildings lining the street, mutilating classic buildings at will, including the destruction of the beautiful Oak Bar of Adler & Sullivan's 1888 Auditorium Building.

And lest you be tempted to think we might actually learn from history, consider the fate of the street's eastern terminus over the last few years. At Michigan Avenue stands Congress Plaza, the only surviving remnant of Burnham's original vision. It's dominated by Ivan Meštrovic's two giant equestrian statues of native Americans, The Bowman and the Spearman, which form a portal to a promenade leading to one of Chicago's greatest civic glories, Buckingham Fountain, and, beyond it, the natural magnificence of Lake Michigan. Despite a major reconstruction in the 1990's, the sweeping plaza still doesn't really work. It doesn't so much flow as just kind of sits there. But you could still make that journey from Michigan Avenue to Buckingham Fountain and Queen's Landing on the lake, so named because it's where a young Queen Elizabeth II made her entrance into Chicago, and feel Burnham's sense of grandeur elevating your very being.

Despite a major reconstruction in the 1990's, the sweeping plaza still doesn't really work. It doesn't so much flow as just kind of sits there. But you could still make that journey from Michigan Avenue to Buckingham Fountain and Queen's Landing on the lake, so named because it's where a young Queen Elizabeth II made her entrance into Chicago, and feel Burnham's sense of grandeur elevating your very being.

Except now you can't even do that. In the course of a single day in the fall of 2005,  without hearings or public discussion of any kind, the Queen's Landing crossing to Lake Michigan was shut down. The traffic light was dismantled, and storm fencing, later replaced with bollards and chains, hastily erected along the fountain side of the Drive. A passerby said a construction worker had told her it was being done because Mayor Daley had become annoyed by having to stop for still another traffic light on a trip to his vacation home in Michigan. We can only hope the story is apocryphal. And so today, visitors are left to glance longingly at the lake kept just beyond their reach, while they contemplate the reality that, to the those who pull Chicago's strings, the interests of the people who actually inhabit the city are expendable; the interests of those who merely want to pass through at the highest possible speed, inviolable.

without hearings or public discussion of any kind, the Queen's Landing crossing to Lake Michigan was shut down. The traffic light was dismantled, and storm fencing, later replaced with bollards and chains, hastily erected along the fountain side of the Drive. A passerby said a construction worker had told her it was being done because Mayor Daley had become annoyed by having to stop for still another traffic light on a trip to his vacation home in Michigan. We can only hope the story is apocryphal. And so today, visitors are left to glance longingly at the lake kept just beyond their reach, while they contemplate the reality that, to the those who pull Chicago's strings, the interests of the people who actually inhabit the city are expendable; the interests of those who merely want to pass through at the highest possible speed, inviolable.

Now that's a fitting subject for a competition honoring Daniel Burnham.

Reclaim Congress Street and restore it to the spirit of Burnham's vision. The challenge becomes progressively tougher as you move west.

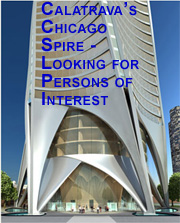

Queen's Landing is most easily remedied. Despite the city's propaganda that the only answer is a costly underpass or an expensive bridge on the order of the striking design by Santiago Calatrava that was unceremoniously trash-canned as soon as it was unveiled, the crossing can be restored without crippling the flow of traffic on Lake Shore Drive with the re-installation of the stoplights, intelligently managed to provide widely timed pedestrian crossing during rush hours, and more frequent ones at other times or when large numbers of people are waiting. Much like the new crossing lights that count down the time remaining before the next red light, the lights at Queens Landing crossing could alert waiting pedestrians as to the time before the next green.

The harbor, itself, is more problematic. In its present state, it's like a surface parking lot crammed bumper to bumper, a long way from Burnham's vision of providing ample harbor facilities within a large development of park land and clear, pleasing vista's. If the city wins the 2016 Olympics, the harbor is scheduled to be emptied out to host rowing events, which could present the opportunity to redevelop the it in a way that also provides lakefront access to non-boaters.Radical proposal: across Lake Shore Drive from Buckingham Fountain, a great beach.

Congress Plaza, at Michigan Avenue, presents a different level of problem. Stretching across two city blocks, it does not lack for space, only presence, appearing windswept and uninviting. Originally designed in 1929 by Edward Bennett, it also suffered in the 1950s: the extension of Congress Street resulted in the destruction of its 100-foot-wide grand staircase. Today, the twin, tall pylons are so far apart, and the site so sliced and diced by Congress Parkway and a curving east Congress Drive that seems to function as little more than a bus

Today, the twin, tall pylons are so far apart, and the site so sliced and diced by Congress Parkway and a curving east Congress Drive that seems to function as little more than a bus  staging area, that the plaza is visually incoherent. The promenade to Buckingham Fountain is dominated by lane after lane of automobile traffic, with pedestrians shuffled off to the singularly graceless peripheries. In the center, what should be the grand axial approach to the fountain is destroyed by the open pit of the Metra tracks.

staging area, that the plaza is visually incoherent. The promenade to Buckingham Fountain is dominated by lane after lane of automobile traffic, with pedestrians shuffled off to the singularly graceless peripheries. In the center, what should be the grand axial approach to the fountain is destroyed by the open pit of the Metra tracks.

Daniel Burnham understood the importance of  gateways, of how, when skillfully designed, they impart a sense of order and proportion to an often chaotic urban fabric. The vista's they create become narratives of the flow of space, structure and energy through a great city.

gateways, of how, when skillfully designed, they impart a sense of order and proportion to an often chaotic urban fabric. The vista's they create become narratives of the flow of space, structure and energy through a great city.

You can get a sense of this at the Michigan Avenue Bridge, a key component of Burnham's 1909 plan. Even though the symmetries of the open spaces have strayed from the clean lines of Burnham's original, the way that the grand plazas and the iconic gateway structures that face them - the cream terra cotta fairy castle Wrigley Building, and the dark gothic traceries of Tribune Tower (it would have worked just as well with Gropius's steel and glass design, by the way) - frame the view towards the old Water Tower, terminating the street in the far distance, remains one of the most eloquent expressions of the uniquely Chicago character.

Chicago has perhaps the most stunning lakefront of any city but, amazingly, while you can access that lakefront through any one of dozens of small entrances, often seedy underpasses punched below Lake Shore Drive, there is not a single great gateway to the lake. The last opportunity for creating one was in the 1980's, just north of Chicago avenue at the new Mag Mile commercial heart of Chicago, and it was squandered when the demolition of the old Illinois National Guard Armory was followed, not by the creation of a grand gateway promenade, but the construction of the bunker-like Museum of Contemporary Art.

In his 1909 plan, Daniel Burnham saw Congress Street as Chicago's great gateway to the lake. What better memorial than to find a way to create it?

Instead, we've got a competition to commemorate the centennial of one the most ambitious and influential plans in the history of architecture with a memorial to the plan's principal author on a leftover lump of land, bereft of any purpose other than sepulchral.

I say, let the dead bury the dead. Chicago lives. It burns and suffers, cries out for wisdom, and expert succor for its wounds. What it doesn't need, to channel the spirit of another great visionary, Buckminster Fuller, are more fossilized nouns. Just like the city he loved, Daniel Burnham wants to be a verb.

Image credits: all photographs and images by Lynn Becker, except: Burnham Memorial competition poster and site plan, AIA Chicago; You're not Invited, the Chicago Architectural Club; Serpentine Gallery images, Serpentine Gallery website, Water Tanks entry, Rahman Polk and the Chicago Architectural Club street plan and rendering of Civic Center, 1909 Plan of Chicago, public domain edition on Google Books; aerial harbor view, 1909 Plan of Chicago, The Burnham Plan Centennial website.

Join a discussion on this story.

© 2009 Lynn Becker All rights reserved.