Repeat- Writings on Architecture: Happy Birthday Louis Sullivan (original) (raw)

A true child of my time, checking my email is the second thing I do after rising each morning and today, after sleeping late, was no exception. The usual assortment of spam and substance - weight loss, stock tips, another comment on a story I did on Adler and Sullivan's endangered George M. Harvey House in Lakeview, but, no, not a comment. As I began to read the message, sent via a Blackberry from a distaught Harvey House neighbor, my heart caught in my throat:

"I stand in front of it while it burns down. Its about 4:30 am and its almost burned completely through the middle."

That's right. Less than two weeks after a massive fire consumed Adler & Sullivan's landmark 1887 Wirt Dexter building in the South Loop, the house the firm completed a year later for George Harvey, in what was then the Chicago suburb of Lakeview, has been gutted by a midnight blaze, its tall brick chimney sent crashing into the building next door.

I had written about the house back in July. The owner had told the local alderman she was going to apply for a demolition permit, and a later story by Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin revealed she had also commissioned drawings for a new condo development on the site. In that same story, owner Natalie Frank stated she had now decided to work to restore the house. Victory was declared, and we all congratulated ourselves on our fine efforts and went back to our lives.

Except, what did we really have? Nothing. Non-binding assurances. The Harvey House was not even an official Chicago landmark. It was on the massive "Orange" laundry list of 9,600 might-be, could-be potential landmarks. An effort to include the  house, and two other historic structures on the same street, in the Hawthorne historic landmark district one block to south had failed in 1996, and even after this summer's threats, nothing was done to give the Harvey House increased protection. And now this.

house, and two other historic structures on the same street, in the Hawthorne historic landmark district one block to south had failed in 1996, and even after this summer's threats, nothing was done to give the Harvey House increased protection. And now this.

The cause of this morning's fire is undetermined. The Chicago Tribune story quotes Fire Department spokesman Kevin MacGregor as saying there were no injuries, and no one was in the house at the time of the blaze. The house has not been occupied by its owner for some time. According to a report on WBBM radio today, there were reports of a loud argument just outside the home not long before the blaze began, and that police "believe the fire was suspicious."

By all accounts, Harvey House owner Natalie Frank is a very nice lady. As I'm sure is Lorraine Philps, the owner of the Wirt Dexter who never was able to scrap  together the money to do proper repairs, and year after year left the structure completely vacant at a time when its South Loop neighborhood has been undergoing a major resurgence, but who still, according to a Chicago Tribune report by Ron Grossman and Josh Noel, responded to an inquiry from Columbia College, which has been buying, saving and renovating turn-of-the-century, landmark-quality buildings throughout the South Loop, with a price the school considered "unrealistically high given the condition of the building." Then salvagers using acetylene torches to disassemble a boiler for scrap started a fire in the Wirt Dexter's basement that raged through the structure, leaving it a collapsing hulk. (It was also the use of acetylene torches that is blamed for a fire that destroyed another Adler & Sullivan masterpiece, K.A.M. Pilgrim Baptist Church, this past January.)

together the money to do proper repairs, and year after year left the structure completely vacant at a time when its South Loop neighborhood has been undergoing a major resurgence, but who still, according to a Chicago Tribune report by Ron Grossman and Josh Noel, responded to an inquiry from Columbia College, which has been buying, saving and renovating turn-of-the-century, landmark-quality buildings throughout the South Loop, with a price the school considered "unrealistically high given the condition of the building." Then salvagers using acetylene torches to disassemble a boiler for scrap started a fire in the Wirt Dexter's basement that raged through the structure, leaving it a collapsing hulk. (It was also the use of acetylene torches that is blamed for a fire that destroyed another Adler & Sullivan masterpiece, K.A.M. Pilgrim Baptist Church, this past January.)

This is Chicago. "Nice" doesn't cut it. Not in a city whose attitude to the destruction of its architectural treasures is often a lazy indifference. This is a city where a Tribune report made it appear that the anger of Richard M. Daley over the Wirt Dexter's loss was confined to the nearly $1 million it cost to put out the fire. This is the city where alderman Burton Natarus, whose 42nd Ward covers much of the city center, will tell anyone in the range of his voice that  he doesn't believe in a landmark protection being forced on owners. In his perfect world, landmark protection would be confined to those building that don't really need it, while it would be open season on those in greatest jeopardy, which could be destroyed at whim. This is a city where developers think so little of the force of landmark protection that one actually got a proposal placed on a recent Landmarks Commission Agenda that called for the panel to approve demolishing an official landmark, Philip Maher's graceful, Mansard-roofed Farwell Building, and slapping its peeled facade onto a new structure that would place a parking garage on north Michigan Avenue, Chicago's Magnificent Mile. (This particular outrage may actually prove a bridge too far - the proposal was pulled from the agenda before the meeting, and has yet to resurface.)

he doesn't believe in a landmark protection being forced on owners. In his perfect world, landmark protection would be confined to those building that don't really need it, while it would be open season on those in greatest jeopardy, which could be destroyed at whim. This is a city where developers think so little of the force of landmark protection that one actually got a proposal placed on a recent Landmarks Commission Agenda that called for the panel to approve demolishing an official landmark, Philip Maher's graceful, Mansard-roofed Farwell Building, and slapping its peeled facade onto a new structure that would place a parking garage on north Michigan Avenue, Chicago's Magnificent Mile. (This particular outrage may actually prove a bridge too far - the proposal was pulled from the agenda before the meeting, and has yet to resurface.)

If a landmark building already has an owner commited to keeping it in good shape - Sullivan's Carson Pirie Scott, Marshall Field's or the Palmer House - the city can slap a plaque on it, police renovations, and the building endures. If a landmark is troubled or neglected, however - Wirt Dexter, or the Uptown Theater - the city doesn't seem to have a clue. The plaque stands; the building is left to rot - the only visible activity is the city's bureaucrats calling press conferences to proclaim how it's all somebody else's problem.

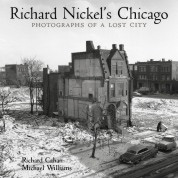

Nowhere is the city's chronic neglect more poignantly documented than in a splendid, just-published book, Richard Nickel's Chicago: Photographs of a Lost City, by Michael Williams and Nickel  biographer Richard Cahan, which contains over 250 Nickel photographs, primarily of destroyed landmarks, often in their death throes. There's a series of stunning shots of the destruction of Adler and Sullivan's 1891 Schiller (Garrick) Theater Building, one of the icons of modern architecture, razed in 1961- while the city stood by - for the construction of a parking garage. The outrage over that singular act of civic vandalism spurred the creation of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, designed to save the city's architectural legacy, yet little more than a decade later, it would prove itself impotent as another Adler & Sullivan masterwork, the 1894 Chicago Stock Exchange Building, was allowed to be demolished for an astonishly mediocre modernist

biographer Richard Cahan, which contains over 250 Nickel photographs, primarily of destroyed landmarks, often in their death throes. There's a series of stunning shots of the destruction of Adler and Sullivan's 1891 Schiller (Garrick) Theater Building, one of the icons of modern architecture, razed in 1961- while the city stood by - for the construction of a parking garage. The outrage over that singular act of civic vandalism spurred the creation of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, designed to save the city's architectural legacy, yet little more than a decade later, it would prove itself impotent as another Adler & Sullivan masterwork, the 1894 Chicago Stock Exchange Building, was allowed to be demolished for an astonishly mediocre modernist  highrise whose sole claim to distinction was that its windows starting popping out shortly after it was completed. Nickel, himself, perished while photographing the Stock Exchange Building's ruined interior. The cover of book's dust jacket is as poetic an expression of the state of architectural preservation as you could imagine - the mansion of Sullivan's partner Dankmar Adler, awaiting its imminent demolition, standing alone amidst a bleak wasteland of empty lots.

highrise whose sole claim to distinction was that its windows starting popping out shortly after it was completed. Nickel, himself, perished while photographing the Stock Exchange Building's ruined interior. The cover of book's dust jacket is as poetic an expression of the state of architectural preservation as you could imagine - the mansion of Sullivan's partner Dankmar Adler, awaiting its imminent demolition, standing alone amidst a bleak wasteland of empty lots.

"The city Richard Nickel photographed is mostly gone," says Cahan in the book's introduction. Now Wirt Dexter and the Harvey House have also, needlessly, crossed the river to join that haunted lost city. Cahan ends with in an injunction that he draws from the testimony of Nickel's poignant images. Today, returning from the embers, disgusted and sick at heart, I can't quite bring myself to believe it. But again tomorrow, I know I must.

Value art. Value life. The opportunity is here.

Join a discussion on this story.

© Copyright 2006 Lynn Becker All rights reserved.