Repeat- Writings on Architecture: Massive Sideshow? (original) (raw)

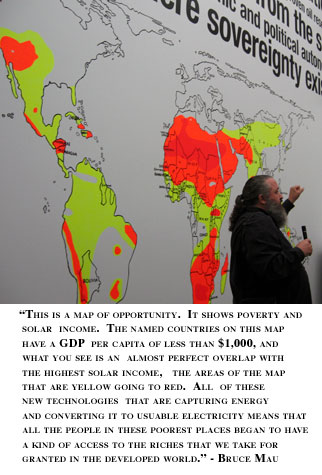

If Massive Change: The Future of Global Design were a movie, people would be calling it the feel-good hit of the season. The exhibition, which opened in September at the Museum of Contemporary Art and runs through December 31st, is the  immensely talented graphic designer Bruce Mau's love letter to the world of design, chockablock with innovative, forward-looking ideas ranging from Hernando de Soto's microloans, to a biodegradable plastic made from potatoes, to an almost entirely recyclable chair, to a vehicle that lets the disabled climb stairs. All that and a featherless chicken to boot. (don’t laugh – according to Mau, America has to get rid of 4.5 billion pounds of feathers a year; you can imagine the quantities of water required to wash them all away.)

immensely talented graphic designer Bruce Mau's love letter to the world of design, chockablock with innovative, forward-looking ideas ranging from Hernando de Soto's microloans, to a biodegradable plastic made from potatoes, to an almost entirely recyclable chair, to a vehicle that lets the disabled climb stairs. All that and a featherless chicken to boot. (don’t laugh – according to Mau, America has to get rid of 4.5 billion pounds of feathers a year; you can imagine the quantities of water required to wash them all away.)

An almost giddy, information-packed display of all kinds of neat stuff, dreamed up  by many of the most brilliant minds of our time, "Massive Change" offers up the same kind of kick world's fairs used to provide, leaving the visitor more than a little drunk with all the possibilities for a better future, full of splendor and friction free.

by many of the most brilliant minds of our time, "Massive Change" offers up the same kind of kick world's fairs used to provide, leaving the visitor more than a little drunk with all the possibilities for a better future, full of splendor and friction free.

You'd think that'd be enough to make a great show, but Mau and his students at the Institute Without Boundaries, a postgraduate design program he founded at George Brown University in Toronto in 2003, thought something more was required, a futurist manifesto whose ambitions are nothing short of millennial: "'Massive Change' is not about the world of design," reads the proclamation at the exhibition's entrance, "it's about the design of the world. . . . You're inside an interface where every object you're about to see leads to a world of change."

If Mau were a cobbler, no doubt he'd see the world progressing through the evolution of shoes, but instead it's design that's the atomic force he sees shaping our existence. "If you can imagine," Mau says, "the number of times you can close your eyes and open them in a space where you're not looking at designed things, you realize that it's almost zero. Your reality is a designed reality." And to Mau, every one of us, like or not, is a conscript in his army. We can no more avoid designing than breathing, he says, and even when we refuse to design, we're designing.

Take a controversial area like genetic engineering, of foods and animals, including ourselves. "Let's say," Mau posits, "that we took a global referendum and said we're  not going to do it, we're not going to design one more thing. We would by that action be responsible anyway because we've decided to take an accidental evolutionary path as opposed to an intentional one." And while the show lays out the hopes and fears implicit to the engineering of plants and animals, Mau's own feelings are unambiguous. "We have every intention of designing life," he says. "In the past it was crude and rough. Today we are quite precise."

not going to do it, we're not going to design one more thing. We would by that action be responsible anyway because we've decided to take an accidental evolutionary path as opposed to an intentional one." And while the show lays out the hopes and fears implicit to the engineering of plants and animals, Mau's own feelings are unambiguous. "We have every intention of designing life," he says. "In the past it was crude and rough. Today we are quite precise."

Perfecting the world may be stickier than Mau imagines. "Massive Change" is so in love with its own brilliance and benevolence that it doesn't seem to notice how marginalized its impact mostly remains, or how easy it is for the centers of power to pay lip service to the spirit of change, patting the designers on the head and shuttling them off to the children's table while the grown-ups run the world with the narrow self-interest - and occasional murderous violence - to which they've become accustomed.

The disconnect is apparent in the very first gallery, which features a row of wonderful alternative vehicles like the Twike, an electric-hybrid two-seater bicycle  enclosed in a lightweight all-weather shell. Its batteries recharge as the rider pedals. "You can get about 100 kilometers out of this for five cents," Mau explains. Actually you can't, because there's no U.S. distributor. You can buy one directly from the European manufacturer (who's apparently backed up through the end of the year) or gawk at it in Neiman Marcus's 2006 Christmas book.

enclosed in a lightweight all-weather shell. Its batteries recharge as the rider pedals. "You can get about 100 kilometers out of this for five cents," Mau explains. Actually you can't, because there's no U.S. distributor. You can buy one directly from the European manufacturer (who's apparently backed up through the end of the year) or gawk at it in Neiman Marcus's 2006 Christmas book.

The next gallery offers a fascinating look at the development of the Segway, the work of Dean Kamen and his company, Deka Research. Among the prototypes on display is the iBOT, a wheelchair capable of climbing stairs or rising up to allow the user to "stand." According to Mau, "Dean looked out of his window one day and saw a man trying  had been sold.

had been sold.

Still another gallery has a prototype of the Model U. "This car is designed," says Mau, "so that all the material can easily disassemble and go back into the production cycle without ever going back into the landfill." In contrast to traditional auto construction methods, the Model U's "materials don't get sandwiched together. They can easily get delaminated and put back into the waste streams in the most effective way."

Except, of course, that they don't, because the car doesn't exist. Back in 2003, Ford's PR people heralded the Model U as "the Model T of the 21st Century . . . a car designed to be good to you and good for the world." That was the concept's high point. In September, of course, the automaker announced it was cutting 45,000 jobs and closing 16 plants. The Model U is nowhere on the production radar.

Massive Change is a faith-based initiative -- Mau has no apparent doubts that his vision will ultimately triumph. At times he seems to inhabit a strange, separate reality, sanitized for his protection, a boy in a bubble that's liable to pop the moment it comes in contact with the real world.

Consider his view on the current state of advertising: "We really think that the era of advertising is over. The idea that you actually say one thing and do another is finished. We used to have a real separation between those two things -- you could run an ad that says this, and then have the worst possible practices inside your company." Apparently Mau has never heard of swift-boating.

Saying one thing and doing another is alive and thriving, as demonstrated by a pair of stories that ran earlier this month. Advertising Age reported that Wal-Mart will pay former Democratic political operative Leslie Dach up to $3 million over the next two years to manage "one of the most ambitious corporate-image makeovers ever,"  and is already airing uplifting TV spots on how the chain's low prices buy a "whole bunch of freedom." And on October 2 the New York Times broke a story on how Wal-Mart, now the largest employer in the U.S., plans to put a cap on wages that are already so low that employees often qualify for welfare, and decimate the ranks of its full-time employees by doubling the percentage of part-time workers from 20 percent to 40 percent. The market, in the person of Wall Street analysts, applauded.

and is already airing uplifting TV spots on how the chain's low prices buy a "whole bunch of freedom." And on October 2 the New York Times broke a story on how Wal-Mart, now the largest employer in the U.S., plans to put a cap on wages that are already so low that employees often qualify for welfare, and decimate the ranks of its full-time employees by doubling the percentage of part-time workers from 20 percent to 40 percent. The market, in the person of Wall Street analysts, applauded.

If you really want to understand how massive change works, listen to Clotaire Rapaille, a psychiatrist who used what he learned in working with autistic children to build a phenomenally successful career as a marketing consultant for Fortune 50 corporations like GM. He did it through the exploitation of a single, simple concept: most of our behavior is controlled not by logic but by what Rapaille calls the "reptilian brain."

Although Toyota launched its first hybrid car, the Prius, in 1997, to a wave of favorable press, it was the SUV -- gas-guzzling and heavy as a tank -- that took off. Rapaille understood perfectly, telling the New York Times in 2000 that these "armored cars for the battlefield" succeeded because they appealed to our deepest fears of crime and violence. "I don't care what you're going to tell me intellectually," Rapaille said in a 2004 Frontline interview, "give me the reptilian. Why? Because the reptilian always wins."

That's a point of view you can bet Karl Rove understands, but I'm not sure Mau does. No doubt that's the sort of counterproductive thinking he says he encountered back when he was first creating "Massive Change," a general mood that was "very negative, pessimistic, and tending to be cynical." He cites historian Arnold Toynbee's conclusion that "the 20th century won't be remembered either for technological invention and innovation or for violence and conflict. Instead it will be understood as the moment in which we dared to imagine the welfare of the entire human race as a practical objective." When he read that Mau thought, "that's exactly the pattern that we can see. Knowing that against that movement there are terrible people, there's greed, there are accidents, there are wars. You have all these sort of negative potentials, but the underlying movement is a movement forward that's extremely positive."

There's something almost obscenely obtuse about such a worldview. The six million Jews who died in the Holocaust, the 60 million lives obliterated by Stalin and Mao, the millions of others liquidated in sundry smaller-scale genocides, all wind up being little more than unfortunate distractions, roadkill on chairman Mau's path to paradise. Can you really overcome the persistent darker aspects of human nature -- can you tame our reptilian brains -- simply by working around them as if they don't exist? "Massive Change" seems to suggest that you can.

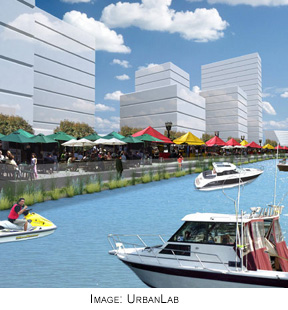

That's why "Sustainable Architecture in Chicago: Works in Progress," an accompanying exhibition at MCA organized by the museum's chief curator, Elizabeth Smith, is such a bracing antidote to the Massive Change's rampaging hyperbole. Instead of  Mau's graphics on steroids, the exhibition is a no-nonsense, almost pedestrian layout of models and renderings. In the place of a manifesto it offers up real projects from seven Chicago architectural firms, each engaging idealism and reality in an interesting way -- from Stanley Tigerman's eco-friendly new home for the Pacific Garden Mission, to UrbanLab's proposals to use transit-oriented development and a new riverwalk to transform gritty downtown Aurora into a more liveable, sustainable city.

Mau's graphics on steroids, the exhibition is a no-nonsense, almost pedestrian layout of models and renderings. In the place of a manifesto it offers up real projects from seven Chicago architectural firms, each engaging idealism and reality in an interesting way -- from Stanley Tigerman's eco-friendly new home for the Pacific Garden Mission, to UrbanLab's proposals to use transit-oriented development and a new riverwalk to transform gritty downtown Aurora into a more liveable, sustainable city.

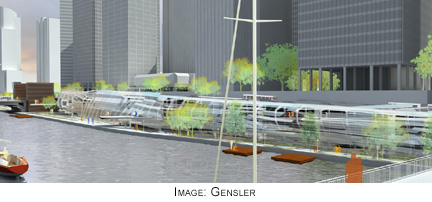

There's Gensler's Elva Rubio's build-out of a riverwalk-enhancing ballroom space under double-decked Wacker Drive just east of Michigan Avenue. Farr Associates bring  their usual mastery of sustainable design to a new headquarters for Greenworks, a new headquarters for Christy Webber Landscapes in an "Eco-Industrial Park" next to the Chicago Center for Green Technology. Jeanne Gang retrieves materials from Lake Calumet's industrial past and recycles them to poetic effect in a visitors facility for the new Ford Calumet Environmental Center, and Helmut Jahn adapts the principles

their usual mastery of sustainable design to a new headquarters for Greenworks, a new headquarters for Christy Webber Landscapes in an "Eco-Industrial Park" next to the Chicago Center for Green Technology. Jeanne Gang retrieves materials from Lake Calumet's industrial past and recycles them to poetic effect in a visitors facility for the new Ford Calumet Environmental Center, and Helmut Jahn adapts the principles  behind his sleek State Street Village dorms at the Illinois Institute of Technology to create a contemporary take on single-room occupancy in a new building on Clybourn.

behind his sleek State Street Village dorms at the Illinois Institute of Technology to create a contemporary take on single-room occupancy in a new building on Clybourn.

Unlike "Massive Change," "Sustainable Architecture" is refreshingly grounded in the here and now. There's something almost comforting in the contradictory human impulses of its final project, a zero-energy skyscraper designed by architects Gordon Gill and Adrian Smith, until recently of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, for the city of Guangzhou, China. The Pearl Tower will use wind, humidity, and solar power to produce more energy than it consumes, thereby sustaining life even as the products of its primary tenant -- a tobacco company -- take it away.

Massive Change runs at Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art through December 31st. Sustainable Architecture in Chicago, for which we hope to have a companion piece on our web site next week, runs through January 7th.

Join a discussion on this story.

© Copyright 2006 Lynn Becker All rights reserved.