“CHEAP” ECONOMY | Maxwell and Halsted (original) (raw)

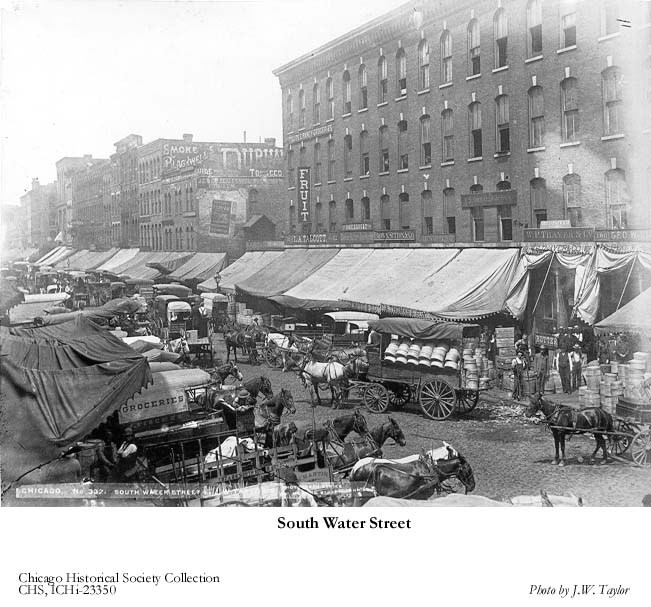

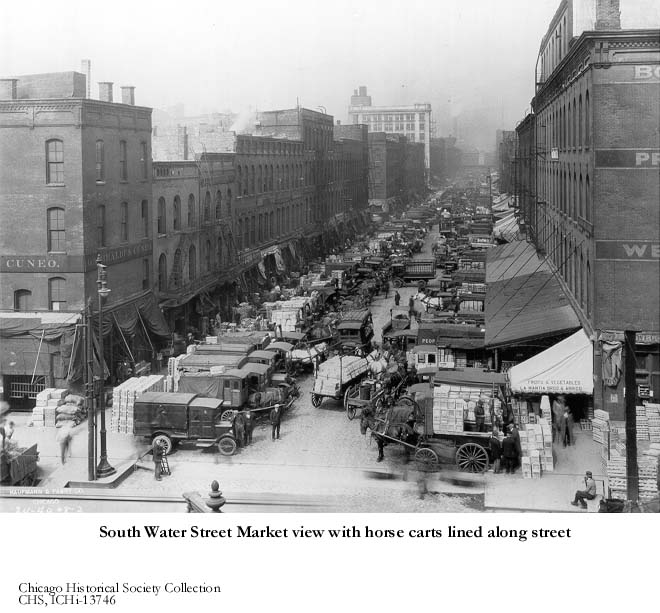

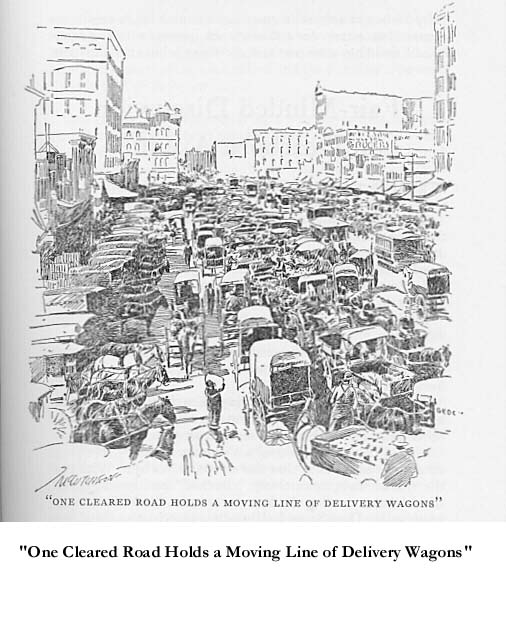

Metropolitan Chicago expanded rapidly in population and size between 1890 and 1910. Significantly, an aggressive consumer-oriented industrial economy was among the drivers of the growth. Geographically central to the nation, an infrastructure or built environment supported the movement of peoples and commerce.

A nexus of railway networks coursed through the city connecting points west, east, and north extending to the Pacific and Atlantic Coasts, and south to the Gulf Coast. Within the city and surrounding it, massive iron works in drawbridges and causeways facilitated water transportation on local canals, rivers, and Great Lake ports. Inter-urban trains, streetcars, and carriages facilitated movement connecting local and distant destinations. With access, local and regional manufacturers seized the opportunity to supply the massive range of goods required to feed the consumption-distribution machine.

In 1906 Sears, Roebuck, and Company built a massive warehouses on Chicago’s West side (three million square feet of floor space) and distributed nearly eight hundred page catalogs with thousands of products indexed, described and illustrated for the rapidly growing mail-order business. In 1896 the postal service had expanded a rural free delivery program into the hinterlands of America which extended quickly to urban centers.

“Cheapest Supply House on Earth,” the header featured the pages of the 1896 Sears Catalog. The “Consumers Guide” known as the American “Bible” (also as “Wish Book,” “Big Book” or “Dream Book”) was sent post-free to millions of American homes, estimated at more than one-quarter of the American population in 1900. Becoming a publicly traded corporation in 1906, Sears innovated as the Amazon of the so-called Gilded Age and the early twentieth-century. In 1925 Sears opened its first brick and mortar retail store on State Street in Chicago. In five years there were more than five hundred retail stores selling iconic Sears brands (Kenmore, Craftsman).

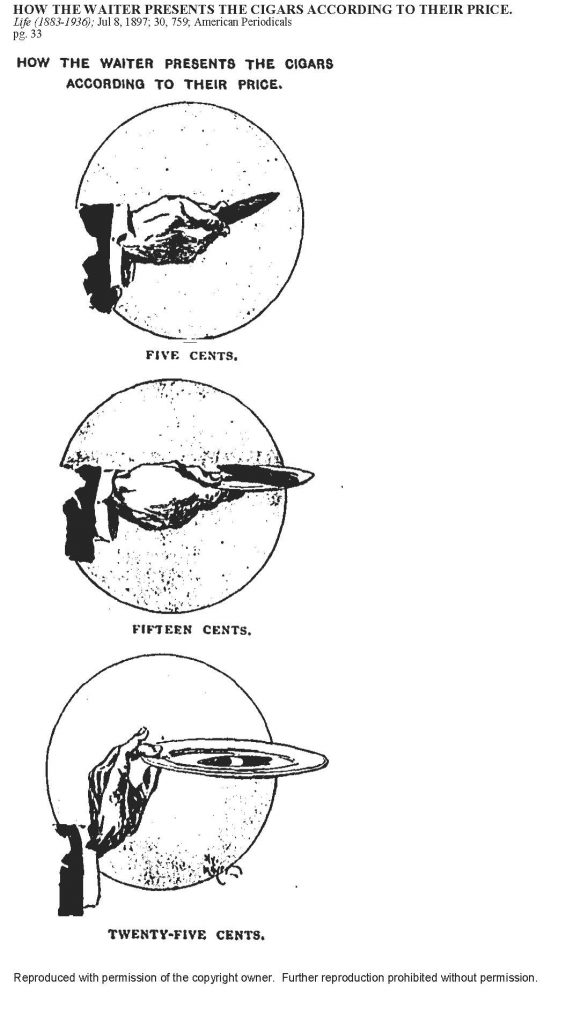

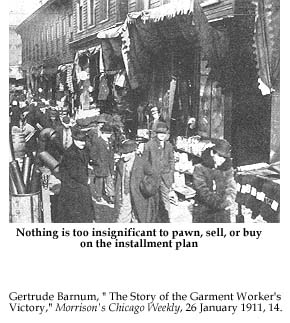

Price mattered and a “cheap” and affordable consumer economy matured in Chicago geared to selling a branded product at a “bargain” aimed at every price-point in a family budget from least costly to most.

From its West Side warehouse, Sears turned over high volume on low profit margins, and supplied reliable products with guarantees for satisfaction and money-back. Garments, personal items, baby products, home repairs equipment, home appliances, tools, bicycles, guns, patent medicines, nostrums including arsenic wafers “to improve the complexion”: you name it, and it quickly appeared listed, often pictured, and available to order.

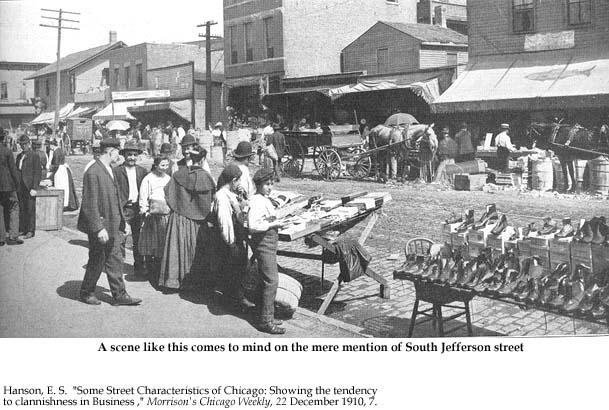

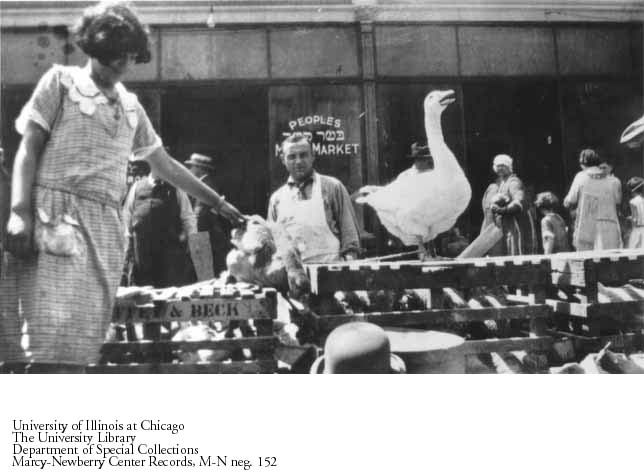

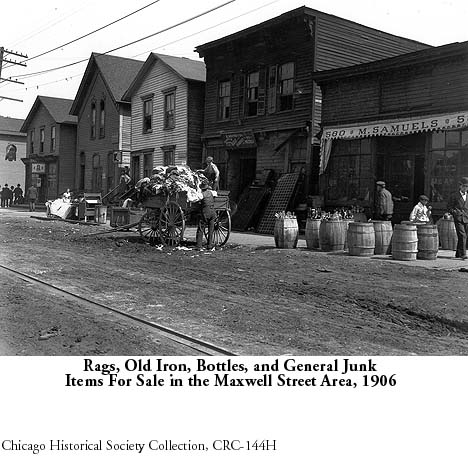

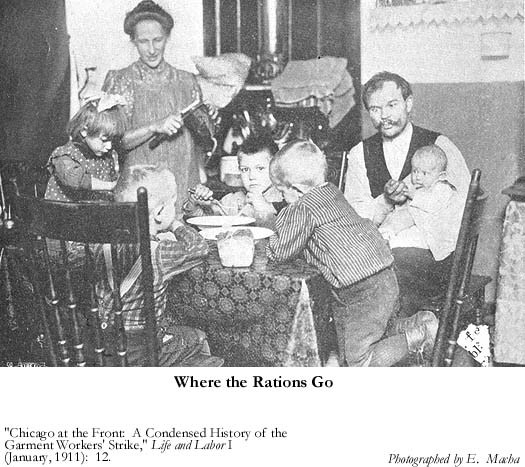

Even before the ascendance of high-end downtown State Street department stores with their decorous genteel clientele, Chicago had become the commercial center of the “goods life” aimed at raising the standard of living for every economic class and income level. With immigrant mothers working in the economy, for instance, among the more popular status items visible in Chicago’s Ghetto from the mail-order catalogs were infant baby carriages paraded along the sidewalks by young siblings taking command. In an era of blatant discrimination against the multitudes of peoples in alien and race colonies, Sears sold to everyone. Making the “goods life” accessible to all comers was a money-maker.

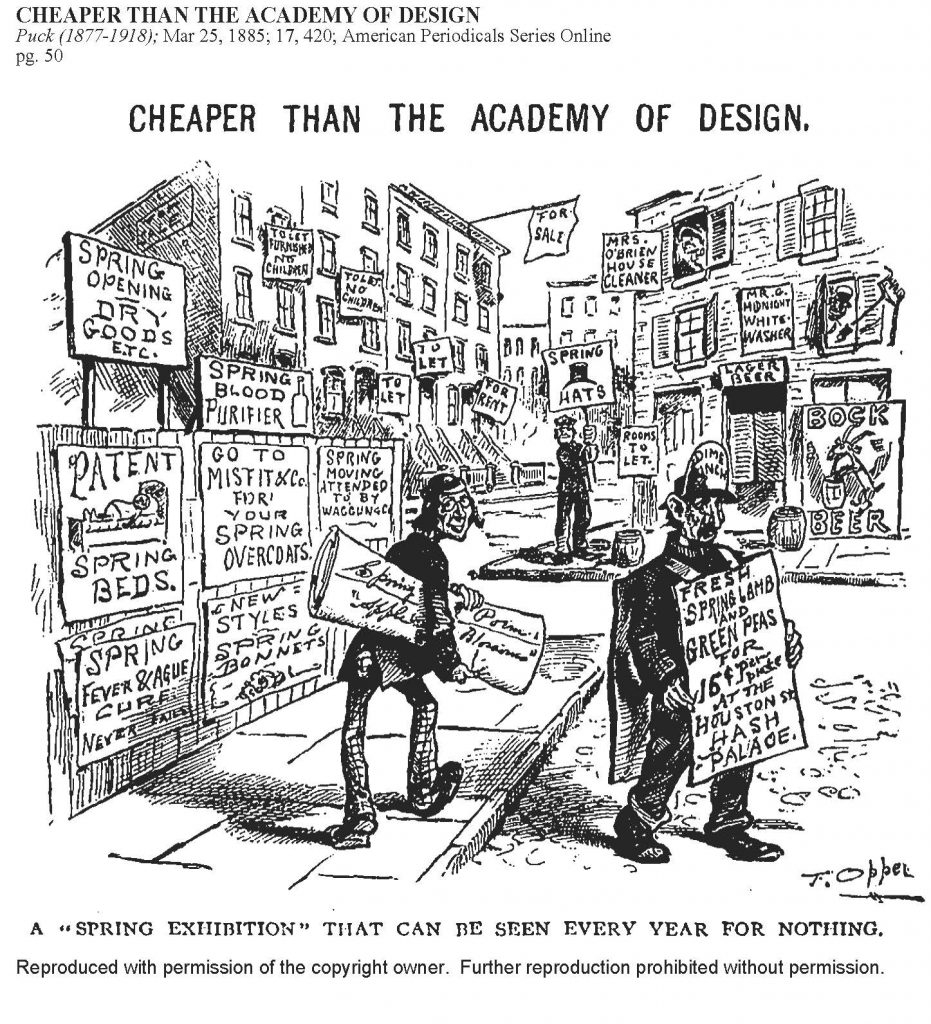

The “cheap” economy dated back to the early nineteenth century. “Cheap” meant solid value for limited budgets–not inferior, chintzy, and shoddy as the monied-classes protested . “Cheap for cash” stores appeared early in the century. By the 1840s modestly priced male and female ready-made garments competing with expensive custom tailor-made suits and dresses were now bought off the rack. Carried by the Federal mails, cheap print (newspapers, magazines, Bibles) circulated with a “cheap” postage stamp (Ben Franklin on its face).

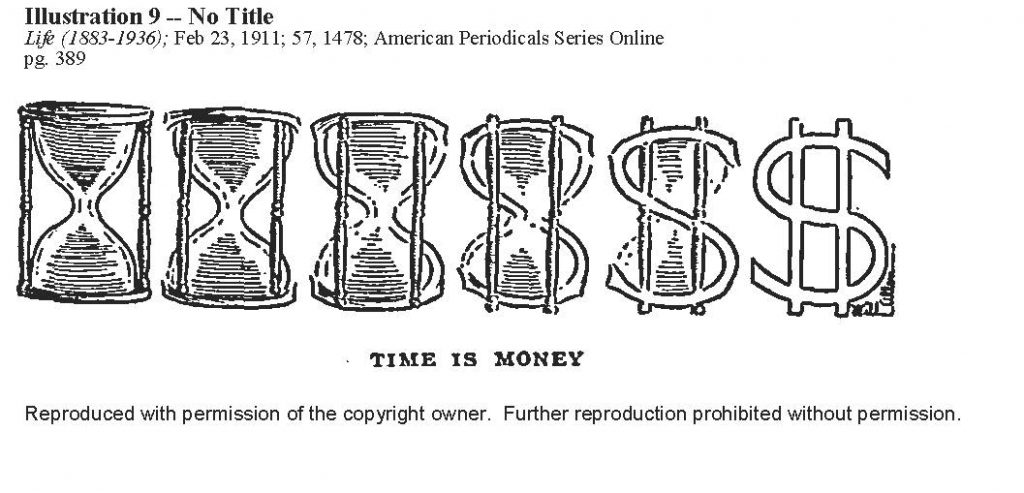

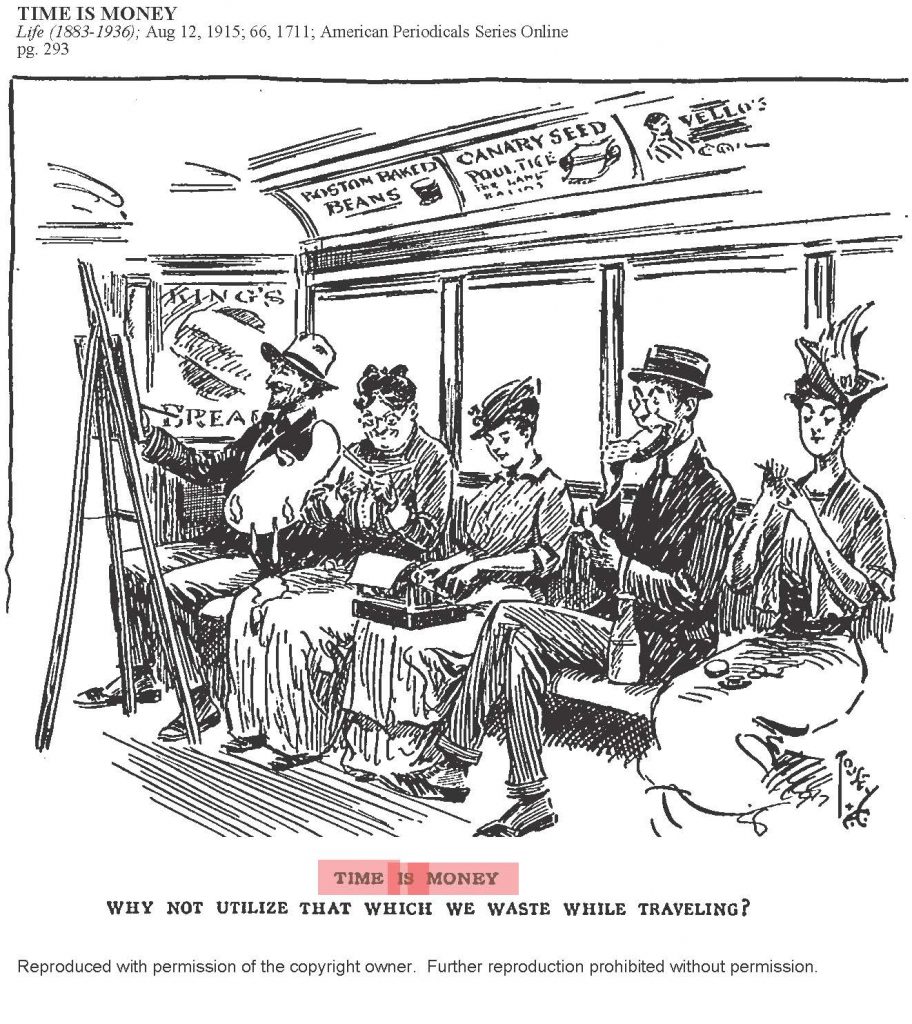

Known from the nursery by every schoolboy, Poor Richard aphorisms–“a penny saved is a penny earned” and “time is money”– empowered the consumer movement. In The American Frugal Housewife: Dedicated To Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy, Lydia Marie Child acknowledged the influence of Franklin’s legacy. On inexpensive paper, Child’s recipe book was reprinted every year from 1833 to 1852, and used for reference in sod-houses on the Western Frontier. “The writer has no apology to offer for this cheap little book of economical hints, except her deep conviction that such a book is needed …. Books of this kind have usually been written for the wealthy: I have written for the poor.”

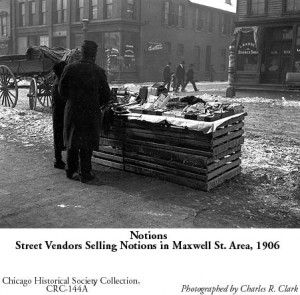

In competitive and capital intensive consumption, price along with quality and durability counted. Grossing large sums and competitive with downtown stores, markets on the West Side pointed to the future of mass market retailing in the U.S.–from Maxwell Street to Sam’s Club, Costco, and now Amazon.com. Continuing to this day, towns in Wisconsin along the Northern Pacific rail line feature a “Maxwell Street Day” with flea-market festivities and local merchants with tables and racks on the streets promoting exceptional bargains by selling off excess and unsold inventories. Amazon.com more recently picked up the practice for its “prime day.”

The success of “purchasing power” in the “cheap” consumer economy set up an historically persistent clash with land-owning farmers and working men in industry including labor unions. They adhered to an eighteenth-century Labor theory of value in which the producers’ hard work–production not consumer demand– determined the primary source of value, to include a “living wage.” “Middlemen”–jobbers, distributors, marketing and sales people–were parasitic, wastefully driving up costs in the economy. The labor theory was and continues to be that cheap goods measured by consumer “purchasing power” priced by the lowest cost of “alien” and “race” labor–“cheap labor”– and State right-to-work legislation robs working people of their rightful earnings and enslaves them.

Conflicting points of view on the “cheap economy” were front and center in the later nineteenth century. Economists debated the impact of “real versus nominal wages” on a working family’s budget. “Marginal utility” theorists shifted value to the least price a willing consumer would pay in a competitive marketplace. Socialists clashed with capitalists in planks on the benefits and liabilities of the “eight-hour movement” for working men and women. bjb

- Sears Roebuck and Co. Consumers Catalogue

- Progress of Technology in the 19th Century

- See Elias Toben kin Ghetto L iving