African Masks and Masquerades –– Minneapolis Institute of Art (original) (raw)

Learn the meanings behind the masks.

Idea One: A transformation takes place when a mask is worn

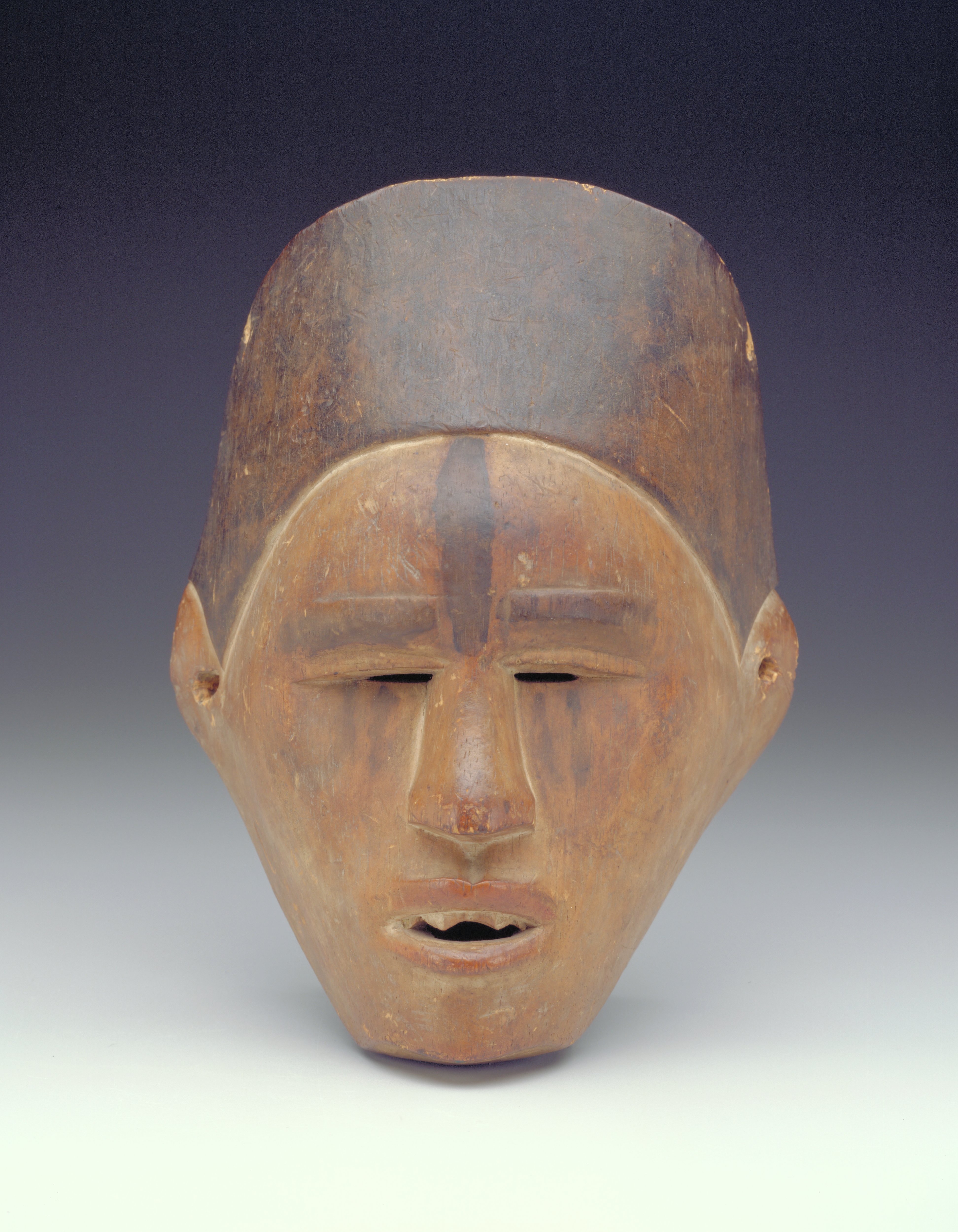

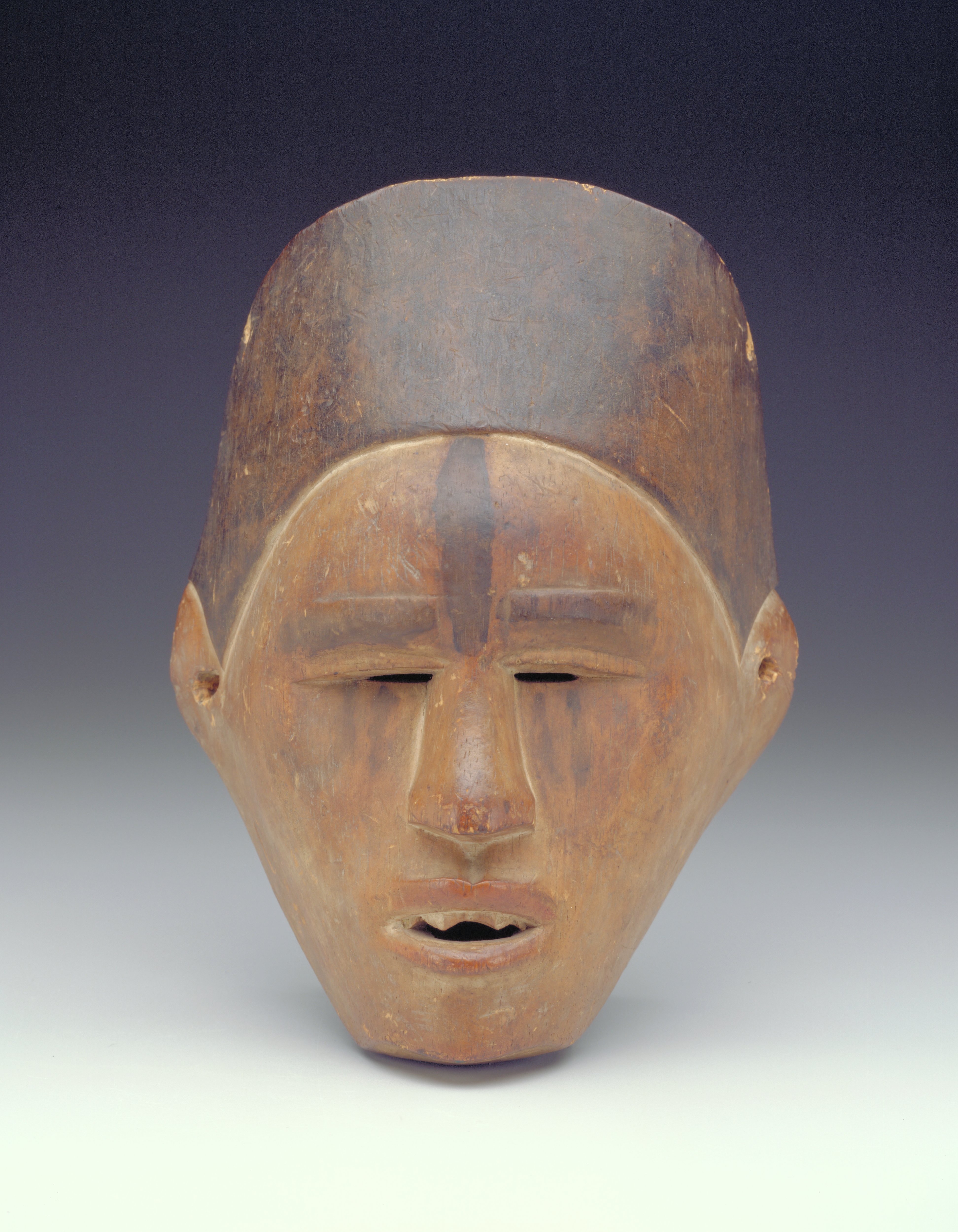

Kpele Kpele Mask, 19th century

Baule

Wood, reconstructed raffia collar

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

In some African cultures, a spirit inhabits a mask upon its creation. When a man (or, on rare occasions, a woman) puts on a mask and costume they give up their own being. The identity of the spirit takes over. Sometimes this spirit can be of another person, such as an ancestor. Other times the spirit is an animal or natural force.

The person who performs with a mask, called a masker, will undergo a physical change. The costume worn with a mask is just as important as the mask itself. A masker dresses in private and covers every inch of their body to conceal their identity. Costumes can be quite complex, made with hoops, padding, poles, and layers of fabric and raffia. Unfortunately, while many museums collect masks, very few costumes survive.

The masked spirit appears to the community in a music and dance performance known as a masquerade. Sometimes the spirit’s movements are unpredictable. Although audience members know that a human being is behind the mask, they accept that the spirit of the mask is present. They may respond to the spirit with fear or joy, depending on the purpose of the spirit’s visit.

This mask represents kpele kpele, a character from a popular masquerade among the Baule people of Ivory Coast.

Mask, 1920-1930

Chokwe

Wood, vegetable fiber, glass beads, metal

THE PUTNAM DANA MCMILLAN FUND

This mask represents a Chokwe ancestor.

Sande mask, second quarter of 20th century

Mende

Wood, raffia

THE CHRISTINA N. AND SWAN J. TURNBLAD MEMORIAL FUND

This Sande Society mask represents a water spirit, sowei.

Horned Forest Spirit Mask,

20th century

Kuba

Wood, cloth, copper, pigment, plant fibers

GIFT OF DAVID AND SARA LIEBERMAN

This Kuba mask from the Democratic Republic of Congo represents a horned forest spirit.

Idea Two: Men and women play different roles in masquerades

Horned Forest Spirit Mask,

20th century

Kuba

Wood, cloth, copper, pigment, plant fibers

GIFT OF DAVID AND SARA LIEBERMAN

Although masks can represent either male or female figures, all maskers all male. In most African communities, although women are not allowed to wear masks, they still participate in masquerades as audience members. They often perform songs and dance to accompany the masker. Women also assist in creating the masker’s costume, sometimes even providing their own clothing for the female figures.

The Sande Society of the Mende in Sierra Leone is one exception to the “men only” rule. The Sande Society is a society of women responsible for teaching young girls the skills and knowledge to become a woman. The spirit, sowei, appears to the young girls several times in the initiation period to provide guidance. The mask, worn by a woman represents an ideal woman. The mask’s delicate facial features, elaborate hairstyle, and rings on the neck represent feminine beauty.

This mask from the Sande Society was worn by a mature woman as part of an initiation ceremony for young girls.

Mask, late 19th century

Yombe

Wood, pigment, kaolin

THE CHRISTINA N. AND SWAN J. TURNBLAD MEMORIAL FUND, THE WILLIAM HOOD DUNWOODY FUND, AND GIFT OF FUNDS FROM BOB ULRICH AND THE REGIS FOUNDATION

This mask has carefully filed teeth, a sign of beauty among the Yombe people. It represents an ideal woman and was probably worn in ritual dances associated with fertility.

Mask, 1920-1930

Chokwe

Wood, vegetable fiber, glass beads, metal

THE PUTNAM DANA MCMILLAN FUND

This mask represents another view of ideal feminine beauty. It was once used in dances to provide an example of how a Guro woman should behave.

Mask, 19th century

Guro

Wood

THE CHRISTINA N. AND SWAN J. TURNBLAD MEMORIAL FUND

This Mwana Pwo (young woman) mask represents the female ancestor of the Chokwe people. It is always worn by a man who is disguised as a woman with a bodysuit, false breasts, and a skirt.

Idea Three: Masks come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and styles.

Helmet mask, 19th century

Luba

Wood, pigments

GIFT OF STEPHEN, PETER, AND MICHAEL PFLAUM IN MEMORY OF THEIR GRANDFATHER ARTHER G. COHEN

This Luba dance mask is worn over the head like a helmet.

Masks can be grouped into three main forms: face masks, helmet masks, and headresses. The face mask is the most common form and usually curves over the masker’s face, stopping right before the ears. Other face masks, often described as plank masks, are completely flat. A helmet mask covers the entire head and sits on the shoulders of the masker. The third form of masks, the headdress, rests on top of the masker’s head. To help keep the masker’s identity disguised, a costume made of raffia or grass is attached to a headdress to cover his or her face.

Some masks take the shape of humans. These masks often have stylized features to represent ideal beauty and strength. Other masks take the form of powerful animals that are important to the community, such as an elephant, antelope, or hawk. Sometimes masks combine attributes from different animals or even combine human and animal features. When these features are brought together on a mask, the powers of each also are combined.

Masks come in a variety of sizes. Sometimes they are very small, just large enough to cover the masker’s face. Other times, they are extremely large or tall. For example, the Bwa mask below is over six feet tall! The masker must be strong to maintain his balance while wearing such a mask.

Misi gwa so’o (Chimpanzee Mask),

20th century, Hemba

Wood

GIFT OF DAVID AND SARA LIEBERMAN

This Hemba mask has half-human, half-chimpanzee features and was used at funerals to symbolize death.

Mbambi Mask, 20th century

Pende

Wood, pigment, raffia

THE ROBERT C. WINTON FUND

This mask used by the Pende people depicts the female antelope Mbambi.

Plank Mask, c. 1960

Bwa

Wood, pigment

THE WILLIAM HOOD DUNWOODY FUND

Bwa plank masks are performed at funerals, initiation ceremonies, and agricultural festivals.

Idea Four: Masquerades mark important events in the community.

Mask, 20th century

Bamum

Wood

THE ETHEL MORRISON VAN DERLIP FUND

This Bamum mask symbolizes an ancestor and is worn at funerals and memorial celebrations. The masker places it on top of his head and wears a mesh veil to cover his face.

Many masquerades mark transitions within the cycle of life. When boys and girls mature from youth to adulthood, masquerades celebrate this life change and teach children how to be adults. Masquerades also play a large role in funeral ceremonies. To help the deceased enter the afterlife, masked spirits appear to honor ancestors, provide protection, and offer guidance.

Masquerade performances honor spirits who bring prosperity to a community. Women are powerful in their communities because they are able to give birth. To help promote fertility, masked spirits perform special ceremonies. Masquerades also are performed at harvest time to honor farming spirits and promote a successful harvest.

Masked spirits can provide protection and help maintain social order. A community may perform a masquerade to ask spirits for protection in war, and against disease and natural disasters. Elders wear masks to call upon ancestors spirits when they need assistance in judging a crime.

Masquerades are also performed at many occasions for simple celebration. These include ancestor celebrations, royal events, religious ceremonies, weddings, and festivals.

Mask, late 19th-early 20th century

Pende

Wood, plant fibers, pigment

GIFT OF FUNDS FROM DARWIN AND GERI REEDY

This mask is worn by a man in the Pende community at iniation ceremonies for boys entering adulthood.

Mask, late 19th century

Yombe

Wood, pigment, kaolin

THE CHRISTINA N. AND SWAN J. TURNBLAD MEMORIAL FUND, THE WILLIAM HOOD DUNWOODY FUND, AND GIFT OF FUNDS FROM BOB ULRICH AND THE REGIS FOUNDATION

The Yombe mask is worn in ritual dances associated with fertility.

Kpele Kpele Mask, 19th century

Baule

Wood, reconstructed raffia collar

THE WILLIAM HOOD DUNWOODY FUND

The kpele kpele mask is worn at elders’ funerals and as village entertainment.

Idea Five: Most African masks are made of wood.

Mask, 20th century

Bamum

Wood

THE ETHEL MORRISON VAN DERLIP FUND

The intricate details on this Lwena dance mask were carved with a small knife.

An artist trained in woodcarving makes the mask. During an apprenticeship, the artist learns about the particular styles of masks that are important to his community. A mask carver is always male and usually holds an important status among his people.

A mask is often made from a single piece of wood. The artist uses an axe-like tool called an adze to create the features on the mask. Fine details are carved on the mask using a knife. To darken or add color to the wood, an artist may soak the mask in mud, burn it, rub it with oil, or paint it with natural pigments or manufactured wood stains. In addition to wood, masks can be made with other materials including beads, bells, feathers, metal, fur, raffia, and shells.

An artist will often make the mask in private. After the artist completes the mask, an elder will perform a ceremony to allow a spirit to inhabit the mask and give it power. Likewise, when a mask is no longer in use the elder performs a ceremony to remove its power.

Ngady Mwaash Mask, 20th century

Bushoong Kuba

Wood, cloth, cowrie shells, beads, pigment, plant fibers

GIFT OF DAVID AND SARA LIEBERMAN

This wood mask from the Bushoong people is decorated with cowrie shells, beads, pigments, plant fibers, and fabric.

Mask, 20th century

Dan

Wood, cloth, metal

GIFT OF MARION AND JOHN ANDRUS

The facial features on this Dan mask are abstract and geometrical. The artist darkened the wood’s natural color.

Elephant Mask, c. 1900

Bamileke

Indigo-dyed cotton, glass beads, natural fibers

THE CHRISTINA N. AND SWAN J. TURNBLAD MEMORIAL FUND

This elephant mask from the Kuosi society is an example of a mask not made from wood. The cloth hood and panels are decorated with beads and raffia.

Related Activities

Experience the Real Thing

Visit The Minneapolis Institute of Art to view the African art collection. Activities to do at the museum include: Identify animals depicted in African masks. Why do you think these animals were honored in their community? What characteristics do they possess? Identify the three mask forms in the galleries: face mask, helmet mask, and headdress. How would it feel to wear these different masks? Compare and contrast the original masks to the website images. How do the sizes, colors, and textures compare? Any surprises?

Masks Here and There

Masks are used in different cultures around the world. How are African masks like the masks you might use? How are the ways you use masks different from the way they are used in traditional Africa? Write down the differences and the similarities.

Animal Hybrids

Many masks depict animal hybrids, combining features of several animals on one mask. Think of three animals found in your environment that you consider powerful. What features make them unique? Design a mask that contains features from each animal.

Compare and Contrast

The Minneapolis Institute of Art owns a large African mask collection. View more masks using the search tool on the museum’s collections website Select two masks and compare and contrast their similarities and differences.

Bibliography

Perani, Judith and Fred T. Smith. The Visual Arts of Africa: Gender, Power, and Life Cycle Rituals (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1998)

Stelzig, Christine. Can you Spot the Leopard? African Masks (New York: Prestel, 1997)