A.I. Is Exploding the Illustration World. Here's How Artists Are Racing to Catch Up | Artnet News (original) (raw)

It’s a scenario that would have been unimaginable a few years ago.

Earlier this month, a popular Korean-language artist who goes by @ato1004fd on Twitch livestreamed an 11-hour sketch session, letting their 22,000 followers watch as they built up an image of a popular character from the video game Genshin Impact.

But by the time @ato1004fd had completed the digital painting, a rogue viewer had already grabbed a picture of the work in process from the stream, used A.I. to “complete” it, and posted their own version to social media—before turning around and accusing @ato1004fd of being the copycat.

“Bro, when you ask your fans to cry about art stealing, [be] reasonable,” the forger wrote. “So you took as reference an AI image but at least admit it.”

A backlash ensued on Twitter where users accused the imposter of gaslighting the original artist. Eventually, the forger deleted their account.

Recent developments in machine-learning programs have turned A.I. into an impressive artistic tool capable of outpacing—and underpricing—human artists, touching off an earthquake in creative circles. Anxieties are highest among graphic artists and commercial illustrators whose livelihood is connected to their ability to turn out content to clients’ specification.

“It’s the Wild West at the moment,” said Liz DiFiore, an illustrator and president of the Graphic Artists Guild. People are primarily worried about their jobs.”

DiFiore cited information from pricing guidelines her organization published last year, which listed an illustrator’s median salary as 50,000,about50,000, about 50,000,about10,000 lower than what the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates as the median annual wage for artists.

“Wages have been decreasing over the years,” she explained. “And infringement is probably the biggest reason why illustrators are seeing the value of their work fall.”

The anime art imposter used an image generator called NovelAI, a monthly subscription service that promises algorithm-assisted authorship and storytelling. The program includes an “image to image” service that allows users to upload images that can be modified through text prompts given to the machine. “The A.I. has essentially learned how to create images—just like a person would,” the company explained in a recent blogpost ending with the words in bold, “Please use our tool responsibly.”

A.I. image generators learn to make artworks based on large datasets with billions of images that have been scraped from the internet. Most artists are unaware that their paintings and prints are housed in these vast online archives; companies believe they are not required to notify the subjects of their vast archive because the information is largely considered public domain.

Greg Rutkowski, Dragon’s Breath (2016). Courtesy of the artist.

In September, Poland-based artist Greg Rutkowski, a major name among fans of fantasy art and gaming, criticized this system after he learned that he had become one of the most popular prompts for image-making algorithms. His name had been used more than 93,000 times and people were beginning to mistake the computer’s output with his own work. One platform, Disco Diffusion, even suggested his name as a prompt.

“A.I. should exclude living artists from its database,” Rutkowski said at the time.

Popular programs like DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion already have policies in place that prevent consumers from using their products in certain ways, like appropriating images of celebrities and politicians.

Portrait of Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon. Image courtesy the artists.

Because the powerful and wealthy have an escape route from the online image-scrapers, many artists have started petitioning companies to delist their work from A.I. training models. Artists Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon recently launched Spawning, a tool intended to allow people to set permissions on how their style and likeness can be used by the machines.

“After years of banging our drum about the significance of training data, there’s now an appetite for discussion,” Dryhurst told Artnet News.

“I understand why artists involved in commercial tasks would be concerned,” he added. “If the fear is that these machines will create satisfactory art (pretty pictures, sculptures with modernist tones) then yes, that fear is valid. I believe that kind of art will be automated in the next couple years.”

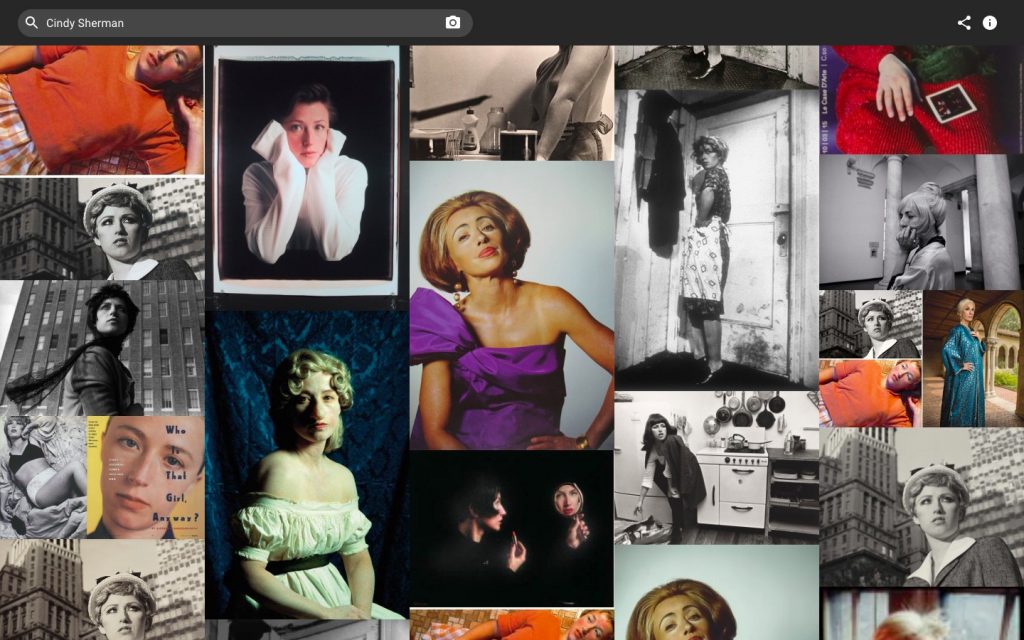

Spawning includes a search function that scours through a dataset called LAION, a 150-terabyte dataset that most A.I. image generators use for training. A quick search of living artists returned thousands of images in the archive of works by Peter Doig, Damien Hirst, Jenny Holzer, Alex Katz, Jeff Koons, Kerry James Marshall, Cindy Sherman, and many more.

Screenshot of results for “Cindy Sherman” from Spawning, a website by Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon.

The rapid adoption of artificial intelligence seems to have surprised most major galleries, which typically exert strict control over anyone using images by their artists. Representatives from Pace Gallery, Gagosian, and Sprüth Magers declined to comment on their policies regarding A.I. image generation.

Legal experts believe that artists, illustrators, and galleries looking to challenge A.I. image generators would have an uphill battle in court. According to Megan Noh, an attorney and co-chair of Pryor Cashman’s art law group, there is not much precedent when it comes to copyright infringement and artificial intelligence.

“The field is very dynamic and evolving,” she said, explaining that plaintiffs would likely need to prove substantial similarity between an original artwork and a generated replica that goes beyond a familiar style. “An artist does not have copyright protection over style,” Noh explained.

Lacking legal recourse, commercial artists have turned to trade organizations for help lobbying the tech companies behind A.I. image generators. DiFiore said that her guild has experienced an increase in membership over the last few weeks because of concerns. “I have spoken to at least three new members who said they joined the guild because we were talking about A.I.”

Despite worries, DiFiore still hopes that the technology could be used to improve the lives of the graphic artists she represents. “AI could eliminate some of the drudgery associated with our jobs like resizing images, generating ad designs, and looking at compositions from different angles,” she said. “These are things that often take time from the parts of the job we enjoy. Any professional would be glad to see efficiency coming to their jobs—while maintaining their wages.”