Sugary Drinks (original) (raw)

Sugary drinks (also categorized as sugar-sweetened beverages or “soft” drinks) refer to any beverage with added sugar or other sweeteners (high fructose corn syrup, sucrose, fruit juice concentrates, and more). This includes soda, pop, cola, tonic, fruit punch, lemonade (and other “ades”), sweetened powdered drinks, as well as sports and energy drinks.

As a category, these beverages are the single largest source of calories and added sugar in the U.S. diet. [1,2] In other parts of the world, particularly developing countries, sugary drink consumption is rising dramatically due to widespread urbanization and beverage marketing. [3]

How sweet is it?

There are 4.2 grams of sugar in a single teaspoon. Now, imagine scooping up 7 to 10 teaspoons full of sugar and dumping it into your 12-ounce glass of water. Does that sound too sweet? You may be surprised to learn that’s how much added sugar is in the typical can of soda. This can be a useful tip to visualize just how much sugar is in your drink. To get you started, we’ve prepared a handy guide to the amount of sugar and calories in popular beverages.

Aside from soda, energy drinks have as much sugar as soft drinks, enough caffeine to raise your blood pressure, and additives whose long-term health effects are unknown. For these reasons, it’s best to skip energy drinks. The guide includes sports beverages as well. Although designed to give athletes carbohydrates, electrolytes, and fluid during high-intensity workouts that last one hour or more, for everyone else they’re just another source of calories and sugar.

Drinks naturally high in sugar like 100% fruit juices are also featured. While juice often contains healthful nutrients like vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, it should also be limited as it contains just as much sugar (though from naturally occurring fruit sugars) and calories as soft drinks.

Sugary drinks and health

When it comes to ranking beverages best for our health, sugary drinks fall at the bottom of the list because they provide so many calories and virtually no other nutrients. People who drink sugary beverages do not feel as full as if they had eaten the same calories from solid food, and research indicates they also don’t compensate for the high caloric content of these beverages by eating less food. [4] The average can of sugar-sweetened soda or fruit punch provides about 150 calories, almost all of them from added sugar. If you were to drink just one of these sugary drinks every day, and not cut back on calories elsewhere, you could gain up to 5 pounds in a year. Beyond weight gain, routinely drinking these sugar-loaded beverages can increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic diseases. Furthermore, higher consumption of sugary beverages has been linked with an increased risk of premature death. [5]

Body weight and obesity

The more ounces of sugary beverages a person has each day, the more calories he or she takes in later in the day. This is the opposite of what happens with solid food, as people tend to compensate for a large meal by taking in fewer calories at a later meal. This compensatory effect doesn’t seem to be present after consuming soft drinks, for several possible reasons:

- Fluids don’t provide the same feeling of fullness or satisfaction as solid foods, as the body doesn’t “register” liquid calories as it does calories from solid food. This may prompt a person to keep eating even after intake of a high-calorie drink.

- It is possible that sweet-tasting soft drinks—regardless of whether they are sweetened with sugar or a calorie-free sugar substitute—might stimulate the appetite for other sweet, high-carbohydrate foods.

- Even though soda may contain more sugar than a cookie, because people think of soda as a drink and a cookie as a dessert they are more likely to limit food than beverages.

Dozens of studies have explored possible links between soft drinks and weight, and they consistently show that increased consumption of soft drinks is associated with increased energy (caloric) intake.

- One meta-analysis of 88 studies showed that the effect appeared to be stronger in women. [6]

- Studies in children and adults have found that reducing sugary drink consumption can lead to better weight control among those who are initially overweight. [7,8]

- An 18-month trial involving 641 primarily normal-weight children randomly assigned to receive either a sugar-free, artificially sweetened beverage (sugar-free group) or a similar sugar-containing beverage (sugar group) found that replacement of sugar-containing beverages with noncaloric beverages reduced weight gain and fat accumulation in the normal-weight children. [9]

- Other studies have found a significant link between sugary drink consumption and weight gain in children. [10] One study found that for each additional 12-ounce soda children consumed each day, the odds of having obesity increased by 60% during 1½ years of follow-up. [11]

- A 20-year study on 120,000 men and women found that people who increased their sugary drink consumption by one 12-ounce serving per day gained more weight over time—on average, an extra pound every 4 years—than people who did not change their intake. [12]

- An updated meta-analysis looking at the association of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) and weight trends in adults and children was published as a follow-up to a 2013 meta-analysis from the same authors. [13] This review of 85 prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials published from 2013 to 2022 included more than 500,000 participants, and again confirmed a strong connection between higher intakes of SSBs and weight gain in both age groups. [14] They also found that a reduced intake of SSBs resulted in weight loss.

- A groundbreaking study of 33,097 individuals showed that among people with a genetic predisposition for obesity, those who drank sugary drinks were more likely to have obesity than those who did not. [15] This study is important because it suggests that genetic risk for obesity does not need to become a reality if healthy habits, like avoiding sugary drinks, are followed. On the other hand, genetic obesity risk seems to be amplified by consuming sugary drinks. Read an interview with the study’s lead researcher.

Alternatively, drinking water in place of sugary drinks or fruit juices is associated with lower long-term weight gain. [16]

Diabetes

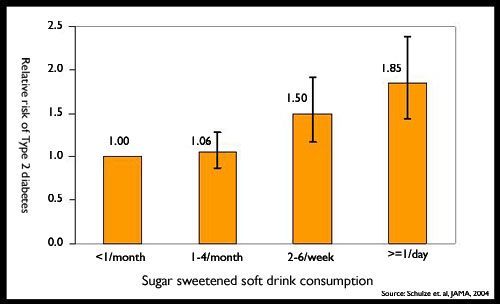

People who consume sugary drinks regularly—1 to 2 cans a day or more—have a 26% greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes than people who rarely have such drinks. [17] Risks are even greater in young adults and Asians.

Strong evidence indicates that sugar-sweetened soft drinks contribute to the development of diabetes.

- The Nurses’ Health Study explored this connection by following the health of more than 90,000 women for eight years. The nurses who said they had one or more servings a day of a sugar-sweetened soft drink or fruit punch were twice as likely to have developed type 2 diabetes during the study than those who rarely had these beverages. [18]

- A similar increase in risk of diabetes with increasing soft drink and fruit drink consumption was seen recently in the Black Women’s Health Study, an ongoing long-term study of nearly 60,000 African-American women from all parts of the United States. [19] Interestingly, the increased risk with soft drinks was tightly linked to increased weight.

- In the Framingham Heart Study, men and women who had one or more soft drinks a day were 25 percent more likely to have developed trouble managing blood sugar and nearly 50 percent more likely to have developed metabolic syndrome. [20]

- A 2019 study looking at 22–26 years’ worth of data from more than 192,000 men and women participating in three long-term studies (the Nurses’ Health Study, the Nurses’ Health Study II, and the Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study) found that increasing total sugary beverage intake—including both sugar sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juice—by more than 4 ounces per day over a four-year period was associated with a 16% higher risk of type 2 diabetes in the following four years. [21]

- Increasing consumption of artificially sweetened beverages by more than 4 ounces per day over four years was linked with 18% higher diabetes risk, but the authors note these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the possibility of reverse causation (individuals already at high risk for diabetes may switch from sugary beverages to diet drinks) and surveillance bias (high-risk individuals are more likely to be screened for diabetes and thus diagnosed more rapidly).

- The study also found that drinking more artificially sweetened beverages in place of sugary beverages did not appear to lessen diabetes risk. However, replacing one daily serving of a sugary beverage with water, coffee, or tea was linked with a 2–10% lower risk of diabetes.

Heart disease

- A study that followed 40,000 men for two decades found that those who averaged one can of a sugary beverage per day had a 20% higher risk of having a heart attack or dying from a heart attack than men who rarely consumed sugary drinks. [22]

- A related study in women found a similar sugary beverage–heart disease link. The Nurses’ Health Study, which tracked the health of nearly 90,000 women over two decades, found that women who drank more than two servings of sugary beverage each day had a 40 percent higher risk of heart attacks or death from heart disease than women who rarely drank sugary beverages. [23]

- People who drink a lot of sugary drinks often tend to weigh more—and eat less healthfully—than people who don’t drink sugary drinks, and the volunteers in the Nurses’ Health Study were no exception. But researchers accounted for differences in diet quality, energy intake, and weight among the study volunteers. They found that having an otherwise healthy diet, or being at a healthy weight, only slightly diminished the risk associated with drinking sugary beverages.

- This suggests that weighing too much, or simply eating too many calories, may only partly explain the relationship between sugary drinks and heart disease. Some risk may also be attributed to the metabolic effects of fructose from the sugar or HFCS used to sweeten these beverages.

- The adverse effects of the high glycemic load from these beverages on blood glucose, cholesterol fractions, and inflammatory factors probably also contribute to the higher risk of heart disease. Read more about blood sugar and glycemic load.

Gout

A 22-year-long study of 80,000 women found that those who consumed a can a day of sugary drink had a 75% higher risk of gout than women who rarely had such drinks. [24] Researchers found a similarly-elevated risk in men. [25]

Bone health

Soda may pose a unique challenge to healthy bones:

- Soda contains high levels of phosphate.

- Consuming more phosphate than calcium can have a deleterious effect on bone health. [26]

- Getting enough calcium is extremely important during childhood and adolescence, when bones are being built.

- Soft drinks are generally devoid of calcium and other healthful nutrients, yet they are actively marketed to young age groups.

- Milk is a good source of calcium and protein, and also provides vitamin D, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and other micronutrients.

- There is an inverse pattern between soft drink consumption and milk consumption – when one goes up, the other goes down. [6]

Liver cancer

Results from a Women’s Health Initiative study following 98,786 postmenopausal women (ages aged 50 to 79) for about 20 years found that participants who drank the highest amounts of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) had an increased risk of liver cancer. More specifically, those drinking 1 or more servings of SSB daily had an 85% higher risk of liver cancer than those who drank 3 or fewer servings of SSB per month. The participants used questionnaires to self-report their intakes of SSB (including soda and fruit drinks but not fruit juice) and diagnosis of liver cancer. The researchers also examined intakes of artificially sweetened beverages, comparing higher intakes of 1 or more servings per day with lower intakes of 3 or fewer servings per month, but did not find any association with liver cancer. [27]

Mortality

According to a large, long-term study of 37,716 men and 80,647 women in the U.S., the more sugary beverages people drink, the greater their risk of premature death — particularly from cardiovascular disease, and to a lesser extent from cancer. [5]

- After adjusting for major diet and lifestyle factors, the researchers found that the more sugary beverages a person drank, the more their risk of early death from any cause increased. Compared with drinking sugary beverages less than once per month, drinking one to four per month was linked with a 1% increased risk; two to six per week with a 6% increase; one to two per day with a 14% increase; and two or more per day with a 21% increase. The increased early death risk linked with sugary drink consumption was more apparent among women than among men.

- There was a particularly strong link between drinking sugary beverages and increased risk of early death from cardiovascular disease. Compared with infrequent drinkers, those who drank two or more servings per day had a 31% higher risk of early death from cardiovascular disease. Each additional serving per day of sugary drink was linked with a 10% increased higher risk of cardiovascular disease-related death.

- Among both men and women, there was a modest link between consumption and early death risk from cancer.

- The study also found that drinking one artificially sweetened beverage per day instead of a sugary one lowered the risk of premature death. However, drinking four or more artificially sweetened beverages per day was associated with increased risk of mortality in women, so researchers cautioned against excessive consumption of artificially-sweetened beverages.

Another long-term study of 18 years from the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study also found that sugary beverages were linked with a higher risk of premature death in more than 15,000 men and women with type 2 diabetes. [28] It found an increased risk of early death from any cause as well as a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and premature deaths from CVD. Replacing sugary beverages with artificially sweetened beverages was associated with a significantly lower risk of CVD incidence and early death in adults with diabetes, even after controlling for weight changes.

Results from a Women’s Health Initiative study following 98,786 postmenopausal women (aged 50 to 79) for about 20 years found that participants who drank the highest amounts of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) had an increased risk of death from chronic liver diseases like nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, and fibrosis. [27] More specifically, those drinking 1 or more servings of SSB daily had a 68% higher risk of death from chronic liver disease than those who drank 3 or fewer servings of SSB a month. The participants used questionnaires to self-report their intakes of SSB (including soda and fruit drinks but not fruit juice) and diagnosis of chronic liver disease. The researchers also examined intakes of artificially sweetened beverages, comparing higher intakes of 1 or more servings per day with lower intakes of 3 or fewer servings per month, but did not find any association with deaths from chronic liver disease.

Sugary drink supersizing and the obesity epidemic

There is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. [29] Unfortunately, sugary beverages are a regular drink of choice for millions around the world, and a major contributor to the obesity epidemic.

Compounding the problem is that sugary drink portion sizes have risen dramatically over the past 40 years, leading to increased consumption among children and adults:

- Before the 1950s, standard soft-drink bottles were 6.5 ounces. In the 1950s, soft-drink makers introduced larger sizes, including the 12-ounce can, which became widely available in 1960. [30] By the early 1990s, 20-ounce plastic bottles became the norm. [31] Today, contour-shaped plastic bottles are available in even larger sizes, such as 1-liter.

- In the 1970s, sugary drinks made up about 4% of U.S. daily calorie intake; by 2001, that had risen to about 9%. [32]

- Children and youth in the US averaged 224 calories per day from sugary beverages in 1999 to 2004—nearly 11% of their daily calorie intake. [33] From 1989 to 2008, calories from sugary beverages increased by 60% in children ages 6 to 11, from 130 to 209 calories per day, and the percentage of children consuming them rose from 79% to 91%. [34] In 2005, sugary drinks (soda, energy, sports drinks) were the top calorie source in teens’ diets (226 calories per day), beating out pizza (213 calories per day). [2]

- Although consumption of sugary drinks in the U.S. has decreased in the past decade, [35] half of the population consumes sugary drinks on a given day; 1 in 4 people get at least 200 calories from such drinks; and 5% get at least 567 calories—equivalent to four cans of soda. [36] These intake levels exceed dietary recommendations for consuming no more than 10% of total daily calories from added sugar [37]

- Globally, and in developing countries in particular, sugary drink consumption is rising dramatically due to widespread urbanization and beverage marketing. [3]

The role of sugary drink marketing

Beverage companies spend billions of dollars marketing sugary drinks, yet generally rebuffs suggestions that its products and marketing tactics play any role in the obesity epidemic. [38]

- In 2013, Coca-Cola launched an “anti-obesity” advertisement recognizing that sweetened soda and many other foods and drinks have contributed to the obesity epidemic. The company advertised its wide array of calorie-free beverages and encouraged individuals to take responsibility for their own drink choices and weight. Responses to the advertisement were mixed, with many experts calling it misleading and inaccurate in stating the health dangers of soda.

Adding to the confusion, studies funded by the beverage industry are four to eight times more likely to show a finding favorable to industry than independently-funded studies. [39]

It’s also important to note that a significant portion of sugary drink marketing is typically aimed directly at children and adolescents. [40]

- A 2019 analysis by the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity found that kids ages 2-11 saw twice as many ads for sugary drinks than for other beverages, and they also saw four times as many ads for certain drinks than adults did. [41] Researchers also analyzed nearly 70 “children’s drinks” (those marketed to parents and/or directly to children), and found that sweetened drinks contributed 62% of children’s drink sales in 2018, including 1.2billioninfruitdrinks(901.2 billion in fruit drinks (90% of children’s sweetened drink sales) and 1.2billioninfruitdrinks(90146 million in flavored, sweetened water sales.

Cutting back on sugary drinks

When it comes to our health, it’s clear that sugary drinks should be avoided. There is a range of healthier beverages that can be consumed in their place, with water being the top option.

Of course, if you’re a frequent soda drinker, this is easier said than done. If it’s the carbonation you like, give sparkling water a try. If the taste is too bland, try a naturally flavored sparkling water. If that’s still too much of a jump, add a splash of juice, sliced citrus, or even some fresh herbs. You can do this with home-brewed tea as well, like this sparkling iced tea with lemon, cucumber, and mint.

What about “diet” sodas or other drinks with low-calorie sweeteners?

Low-calorie sweeteners (LCS) are sweeteners that contain few to no calories but have a higher intensity of sweetness per gram than sweeteners with calories. These include artificial sweeteners, such as Aspartame and Sucralose, as well as extracts from plants like steviol glycosides and monk fruit. Beverages containing LCS sometimes carry the label “sugar-free” or “diet.” The health effects of LCS are inconclusive, with research showing mixed findings. A 2018 scientific advisory by the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association noted that further research on the effects of LCS beverages on weight control, cardiometabolic risk factors, and risk of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases is needed. That said, they also note that for adults who are regular high consumers of sugary drinks, LCS beverages may be a useful temporary replacement strategy to reduce intake of sugary drinks.

Learn more about the research on LCS in foods and beverages.

Action beyond the individual level

Reducing our preference for sweet beverages will require concerted action on several levels—from creative food scientists and marketers in the beverage industry, as well as from individual consumers and families, schools and worksites, and state and federal government. We must work together toward this worthy and urgent cause: alleviating the cost and the burden of chronic diseases associated with the obesity and diabetes epidemics in the U.S. and around the world. Fortunately, sugary drinks are a growing topic in policy discussions both nationally and internationally. Learn more about how different stakeholders can take action against sugary drinks.

Related

Healthy Drinks

Public Health Concerns: Sugary Drinks

Spotlight on Soda

Healthy kids ‘sweet enough’ without added sugars

References

- Hu FB, Malik VS. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Physiology & behavior. 2010 Apr 26;100(1):47-54.

- National Cancer Institute. Sources of Calories from Added Sugars among the US population, 2005-2006. Risk Factor Monitoring and Methods Branch Web site. Applied Research Program. Mean intake of added sugars & percentage contribution of various foods among US population. http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/foodsources/added_sugars/.

- Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013 Jan;9(1):13.

- Pan A, Hu FB. Effects of carbohydrates on satiety: differences between liquid and solid food. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2011 Jul 1;14(4):385-90.

- Malik V, Li Y, Pan A, De Koning L, Schernhammer E, Willett W, Hu F. Long-Term Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Mortality in US Adults. Circulation. 2019 Mar 18.

- Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of public health. 2007 Apr;97(4):667-75.

- Chen L, Appel LJ, Loria C, Lin PH, Champagne CM, Elmer PJ, Ard JD, Mitchell D, Batch BC, Svetkey LP, Caballero B. Reduction in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with weight loss: the PREMIER trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009 Apr 1;89(5):1299-306.

- Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK, Chomitz VR, Ellenbogen SJ, Ludwig DS. Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatrics. 2006 Mar 1;117(3):673-80.

- de Ruyter JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Oct 11;367(15):1397-406.

- Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and BMI in children and adolescents: reanalyses of a meta-analysis. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009 Jan 1;89(1):438-9.

- Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. The Lancet. 2001 Feb 17;357(9255):505-8.

- Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 Jun 23;364(25):2392-404.

- Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2013 Oct 1;98(4):1084-102.

- Nguyen M, Jarvis SE, Tinajero MG, Yu J, Chiavaroli L, Mejia SB, Khan TA, Tobias DK, Willett WC, Hu FB, Hanley AJ. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2023 Jan.

- Qi Q, Chu AY, Kang JH, Jensen MK, Curhan GC, Pasquale LR, Ridker PM, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Chasman DI. Sugar-sweetened beverages and genetic risk of obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Oct 11;367(15):1387-96.

- Pan A, Malik VS, Hao T, Willett WC, Mozaffarian D, Hu FB. Changes in water and beverage intake and long-term weight changes: results from three prospective cohort studies. International journal of obesity. 2013 Oct;37(10):1378.

- Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes care. 2010 Nov 1;33(11):2477-83.

- Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004 Aug 25;292(8):927-34.

- Palmer JR, Boggs DA, Krishnan S, Hu FB, Singer M, Rosenberg L. Sugar-sweetened beverages and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in African American women. Archives of internal medicine. 2008 Jul 28;168(14):1487-92.

- Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Meigs JB. D, Agostino RB, Gaziano JM, Vasan RS: Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation. 2007;116:480-8.

- Drouin-Chartier JP, Zheng Y, Li Y, Malik V, Pan A, Bhupathiraju SN, Manson JE, Tobias DK, Willett WC, and Hu FB. Changes in Consumption of Sugary Beverages and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Subsequent Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Results from Three Large Prospective U.S. Cohorts of Women and Men. Diabetes Care. online 2019 Oct 3.

- De Koning L, Malik VS, Kellogg MD, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption, incident coronary heart disease, and biomarkers of risk in men. Circulation. 2012 Apr 10;125(14):1735-41.

- Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009 Feb 11;89(4):1037-42.

- Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA. 2010 Nov 24;304(20):2270-8.

- Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Feb 7;336(7639):309-12.

- Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review–. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006 Aug 1;84(2):274-88.

- Zhao L, Zhang X, Coday M, Garcia DO, Li X, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Naughton MJ, Lopez-Pentecost M, Saquib N, Shadyab AH, Simon MS. Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Liver Cancer and Chronic Liver Disease Mortality. JAMA. 2023 Aug 8;330(6):537-46.

- Ma L, Hu Y, Alperet DJ, Liu G, Malik V, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Hu FB, Sun Q. Beverage consumption and mortality among adults with type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2023 Apr 19;381.

- Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar‐sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity‐related diseases. Obesity reviews. 2013 Aug;14(8):606-19.

- The Coca-Cola Company. History of Bottling. Accessed June 2013: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/our-company/history-of-bottling

- Jacobson M. Liquid Candy: How Soft Drinks are Harming Americans’ Health. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest; 2005.

- Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004 Oct 1;27(3):205-10.

- Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988–2004. Pediatrics. 2008 Jun 1;121(6):e1604-14.

- Lasater G, Piernas C, Popkin BM. Beverage patterns and trends among school-aged children in the US, 1989-2008. Nutrition journal. 2011 Dec;10(1):103.

- Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States–. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2011 Jul 13;94(3):726-34.

- Ogden CL, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Park S. Consumption of sugar drinks in the United States, 2005-2008. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2011 Aug.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

- Coca-Cola: Don’t blame us for the obesity epidemic! The New York Daily News June 8, 2012.

- Lesser LI, Ebbeling CB, Goozner M, Wypij D, Ludwig DS. Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles. PLoS Medicine. 2007 Jan 9;4(1):e5.

- US Federal Trade Commission. Marketing Food to Children and Adolescents: A Review of Industry Expenditures, Activities, and Self-Regulation. Washington, DC: US Federal Trade Commission; 2008.

- Harris J, Romo-Palafox M, Choi Y, Kibwana A. Children’s Drink FACTS 2019: Sales, Nutrition, and Marketing of Children’s Drinks. UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; 2019.

Last reviewed August 2023

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.