Norman Foster: My Mentor Buckminster Fuller Was Built to Last (original) (raw)

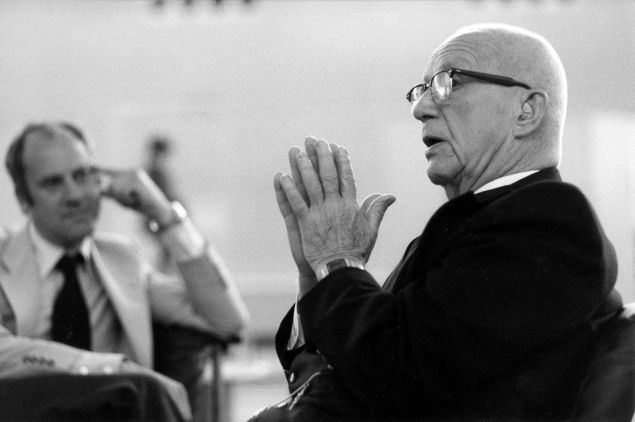

Sir Norman Foster, left, and his mentor Buckminster Fuller (Photo courtesy of Sir Norman Foster).

I remember vividly my first meeting with Buckminster Fuller—or Bucky as he was more commonly known. It was in 1971 and he had been asked to design a theater beneath the quadrangle of St Peter’s College, Oxford and was looking for an architect to collaborate with. We met at The Institute of Contemporary Arts, which at that time had a paneled dining room overlooking the Mall. In this elegant setting we talked through a long lunch. Looking back, it is ironic to think we first met in such an architecturally traditional setting. That theater project—like all of Bucky’s work—was to be truly innovative, a complete break with the past in the context of Oxford. Bucky decided on the spot that we should work together and headed off to the next engagement on his punishing schedule.

On another occasion, in the midst of trying to describe the form of the theater, he ran into the bathroom and came back with a bar of soap, saying, “This is what it would look like.” Inscribing into the soft surface of the soap the words “Oxford Beckett Theatre,” he then signed it with a flourish. Bucky had a wonderfully evocative way of acting out how the forces of nature would work on his structures. Allied to his willingness to explore new techniques was a concern for economy of means. Bucky spoke frequently, for example, about the relationship between weight, energy and performance—of “doing the most with the least”—and that has consistently been the story of technological progress. Soon our understanding became far more sophisticated; we were more aware of the unifying qualities of energy systems and the environment. Today we are applying his thinking at a regional scale but always conscious, as Bucky extolled, to “Think global, act local.”

Bucky was the very essence of a moral conscience, forever warning about the fragility of the planet and man’s responsibility to protect it.

It is only now that I realize the extent to which Bucky was able to draw me out through our conversations without my realizing it. Bucky got me to reveal attitudes to design, materials, research and other issues, which ranged far and wide. Looking back over the 12 years of our collaboration and friendship there are many papers that could be written on the insights that Bucky offered. But perhaps the themes of shelter, energy and the environment—which go to the heart of contemporary architecture—best reflect Bucky’s inheritance and his importance to me as a mentor.

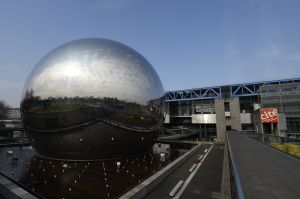

Buckminster Fuller was known for designing geodesic domes (BERTRAND GUAY/AFP/Getty Images).

For me, Bucky was the very essence of a moral conscience, forever warning about the fragility of the planet and man’s responsibility to protect it. His public image was often that of a cold technocrat. But that could not be further from the Bucky I knew; he was poetic, sentimental and had a deeply spiritual dimension. He was one of those rare individuals who could fundamentally influence the way that you come to view the world.

Norman Foster is chairman and founder of Foster + Partners, an architecture firm based in England.

Please also read:

Chuck Todd on Tim Russert et al.

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand on her grandmother Polly Noonan

Neil deGrasse Tyson on Carl Sagan

Richard Edelman on his father Daniel Edelman

Matthew Modine on Robert Altman

Gus Lee on General Norman Schwarzkopf